| Dominic Lennard Bad Seeds and Holy Terrors: The Child Villains of Horror Film State University of New York Press, 2015 ISBN: 9781 4384 5328 6 US$24.95 (pb) 195pp (review copy supplied by SUNY Press) |

|

Andrew Scahill notes in his 2010 essay on The Exorcist (1973), wittily titled “Demons Are a Girl’s Best Friend”, that the child-as-monster in horror film has “yet to be given substantial treatment in critical accounts of the genre”. As if on cue, Scahill’s comments seemingly triggered a veritable avalanche of scholarship that has only intensified. At the time of printing, Scahill’s observation was accurate insomuch as research in the field was fragmentary. While an impressive array of work has been published subsequent to Scahill’s contention, much of this remains piecemeal due in large part to the continued absence of a full-length study.

Dominic Lennard’s Bad Seeds and Holy Terrors: The Child Villains of Horror Film is the first scholarly book by a single author focussed entirely on the topic of monster children in film. This accomplishment is highlighted on the back cover of the book. Covering familiar theoretical terrain across a wide range of films while drawing on some of the key writers on monster children in film, this is a welcome though at times redundant addition to a field diffuse in its multidisciplinarity.

Combining cultural studies, psychoanalysis, gender and childhood studies with film history and close analytical readings of his chosen film texts, Lennard explores some of the various contradictory ways of approaching the child as social construct and monstrous other. Driving the study is an examination of the central problem of why adults depict children as monsters and Lennard takes his cue from existing discourses on monster children.

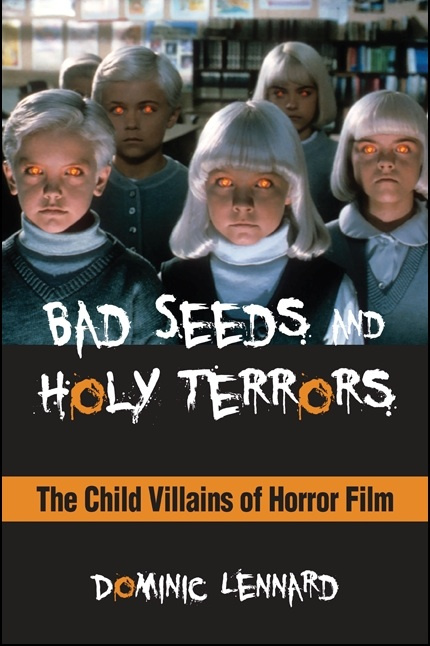

The book comprises nine concise chapters loosely divided into three thematic sections. Reminiscent of William Paul’s substantial chapter on children in horror films, the first section considers the social context and influence of monster child films in the postwar era. The Bad Seed (1955) is commonly held to be the first bona fide monster child film and Lennard does not challenge this popular assumption. Instead he commits his first two chapters to close analytical readings of LeRoy’s 1955 film, the first of which considers juvenile delinquency and youth culture in the postwar period while the second looks at Rhoda’s bourgeois classism. It was disappointing to see Lennard open his study with The Bad Seed. When research on monster children should be looking for antecedents, of which there are countless, Lennard’s book erroneously dismisses earlier incarnations of monster children. A third chapter on Village of the Damned (1995) applies Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure essay to the child, made monstrous by its controlling gaze.

The second section addresses the theme of parental complicity in producing monstrous offspring across a range of films that include The Brood (1979), The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992), The Ring (2002), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Omen (1976) and It’s Alive (1974). Monstrous parents, it is asserted, beget monstrous progeny. The first two chapters of this section look at expressions of motherhood from mollycoddling to neglect and how women, regardless of their actions, are blamed for producing recalcitrant offspring. Lennard does not overlook the role of the father however and includes a chapter observing ways that monster children threaten patriarchy and how the child’s teratology might be read as a signifier of paternal weakness and patriarchal collapse.

The book’s final section contains three chapters investigating the adult/child nexus, dispensing with biological definitions of the child and approaching adults as children. The first of these chapters continues with the theme of flawed masculinity introduced in the previous chapter and applies it to The Exorcist. Lennard’s focus on Karras is a refreshingly unique contribution to monster child scholarship that invariably positions Regan at its core. His close reading of the film’s editing shows how Friedkin’s use of juxtaposition conflates Karras’ failure in his duties as a son with his ineffectuality as a “Father”.

A chapter on the 1988 Tom Holland film Child’s Play (1988) maintains that in the 1980s, permissive parenting and marketers targeting youth transformed children into insatiable consumer monsters whose endless demands empty parents’ pockets. Lennard’s reading of the film is compelling and he convincingly argues for its inclusion in the monster child canon, yet much of what he discusses reminded me of existing scholarship on The Bad Seed that analyses its representation of permissive parenting and unbridled greed within the context of America’s postwar economic boom. Significantly, in Child’s Play the economic boom is replaced by a recession that has important implications on how to read the film that the chapter overlooks.

The final chapter demonstrates how Hard Candy (2005) and Orphan (2009) manipulate audience anxiety around paedophilia. Lennard discusses how in both films the child is problematically portrayed as the instigator of paedophilic desire that is eventually disavowed as their age and identity is revealed. Readers may locate connections between this chapter and the earlier chapter on scopophilia and the child’s to-be-looked-atness although these connections are not made explicit in the book.

Adding unique insights while revising well-trodden critical ground, the value of Lennard’s book is in its eloquent and well-researched consolidation of existing scholarship in the field, making it a useful introductory text for researchers and students.