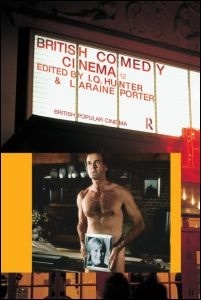

| I.Q. Hunter & Laraine Porter, British Cinema Comedy London and New York: Routledge, 2012 ISBN: 978 0 415 6666 7 1 UK £24.99 (pb) 228pp (Review copy supplied by Routledge) |

|

This is undoubtedly one of the best and most comprehensive genre collections in the Routledge British Popular Cinema series to have appeared so far. Covering familiar ground such as Ealing comedies and the Carry On series, the collection also examines silent and early sound comedies, unfamiliar to those of us who do not reside in the UK, as well as recent examples of working-class comic stereotypes (Britain’s own version of Hollywood gross-out films) and the role of animation. One very welcome chapter covers the output of the usually marginalized Mancunion Film Company by University of Salford expert C.P. Lee, a leading expert on North West Cinema and curator of that indispensable website http://www.itsahotun.com. Little did I know that, during the 1970s when I watched rehearsals for Granada TV’s <em>Movie Quiz</em>, I was on that hallowed ground in Manchester’s Dickinson Road where Frank Randall and others made their own iconoclastic brand of comedic films.

In these dismal times we all need a good laugh (as my offering a second class on Jerry Lewis this semester reveals!). I remember those BBC television shows of the 1950s when local comedians such as Norman Evans, Sandy Powell, and Nat Jackley were making their final twilight career moves into a new technology far different from the music hall and low budget film venues that occurred during their peak years. This collection of essays represents a sterling tribute to a diverse vein of British comedy that has usually focused on the ‘usual suspects’ such as Gracie Fields, George Formby, Ealing and Carry On, to the neglect of other areas worthy of excavation and possible international promotion – now that we have further new technologies, such as the internet and DVD, that will make this area more accessible than ever before.

The collection comprises fifteen essays all concisely written with meticulous footnote documentation from archives, newspaper and internet sources that cover many areas, from the silent cinema to the present day. It opens with an informative introductory essay by the editors that not only introduces the individual articles but also places them in a very informed historical and cultural context revealing that the transcultural arena should not be marginalized in favor of the national background. While local comedians emerged at the beginning in the music hall (some never making films until they migrated to America), others like American actress-producer Florence Turner represented a hybrid mixture of cinematic and vaudeville styles until her return home in 1916. In her well-documented study of pre-1930 British slapstick routines Laraine Porter notices popular comedian Betty Balfour’s attempts to broaden her range of performance in later films that were hindered by gender and industrial constraints. The subject of female comedians is worthy of a study in its own right in terms of such considerations and Porter has provided some suggestive directions especially if we consider cases such as Mabel Normand and Minta Durfree. Class also raises its nuanced (but not so ugly) head in Lawrence Napper’s examination of certain 1930s comedies where he notices a far more complex operation of the subject in his selected examples. C.P. Lee’s investigation of Mancunion Studios is exemplary in many ways not only in excavating sometimes forgotten comedians and local trends but also in suggesting a particular form of transatlantic influence. One 1933 still shows Laurel and Hardy with studio head Blakely and comedian Bert Tracey who had gone to America with Chaplin and Laurel with the Fred Karno Company, and worked in American silent comedy before returning to Manchester in 1927. The meeting occurred in the Manchester Midland Hotel, the same venue where Cary Grant would meet the Blakelys almost thirty years later. Until reading this informative essay, I did not know that Gracie Fields’s brother Duggie Wakefield had also worked in America before returning home. This really makes the Jerry Lewis film Funny Bones (1995), mostly shot in Blackpool, of added relevance in terms of its transatlantic comic suggestions. The rest of the essay covers the work of Frank Randall, the comic Northern Mr. Hyde to George Formby’s Jekyll, whose ‘bad boy’ comedy needs wider recognition.

Ealing comedies and the Boulting Brothers receive added relevant historical contextualization while the comic talents of Margaret Rutherford are insightfully compared to Manny Farber’s definition of ‘termite art’ by Sarah Street. James Chapman’s ‘A Short History of the Carry On films’ is a brief but very concise description of this iconoclastic corpus as is Andrew Robert’s essay on the St. Trinian’s films. Richard Dacre makes a very convincing case for recognizing the often critically despised Norman Wisdom as “Britain’s finest film comic.” (139) Like all comic geniuses Wisdom pioneered a specific type then found it difficult to break away from it though not with the sad spectre represented by Tony Hancock. However, like Martin and Lewis, Dacre notes that Wisdom’s live performances often surpassed his film routines. Significantly, he did have an international following in places such as South America, Hong Kong, Iran, the Soviet Union, and Albania.

Television sit-com adaptations and Monty Python films receive appropriate coverage and I will thankfully take I.Q.Hunter’s word about the grotesque working-class comic stereotype films he has viewed. “Having watched these films so you don’t have to…”(154). He provides enough evidence to justify his conclusion of seeing these films isolated from what was once a genuine culture but now conveying “racism, sexism, and homophobia” (168) – to say nothing about class contempt against the less affluent members of British society. Two concluding essays deal with the comic scripts of Richard Curtis in relation to a changing British culture by James Leggott and comic elements in British animation by Paul Wells.

Overall, this is a very insightful collection of essays, several of which provide new insights that will stimulate future work in this subject. But future writers will face the challenge of recognizing that they have a ‘hard act to follow’.