Part 3c[1]

Introduction to Part 3c

[Young Mr Lincoln (1939)]

[Drums Along The Mohawk (1939)]

[The Grapes of Wrath (1940)]

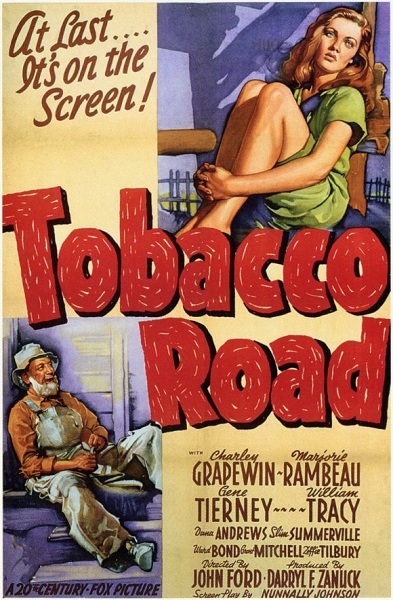

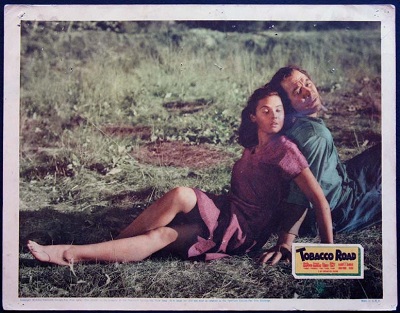

Tobacco Road (1941)

– The question of mode

– The novel

– The play

– The screenplay

– Lindsay Anderson

– Not resolved

– Characters and their treatment

– Two wrong directions

– Addendum askew: The Primrose Path

– Honi soit qui mal y pense

[How Green Was My Valley (1941)]

This section is quite a bit longer than those that have gone before. The reason is that I have felt it necessary to write more about the “acknowledged classics” of this period because, taken together, they so clearly provide one of the most important contexts for understanding the one minor work, Tobacco Road, and set the tone for a great deal of Ford’s work for the rest of his career. At the same time you mustn’t expect finished or exhaustive analyses of the better known films, only somewhat expanded notes.

There is another context that may help to set the scene for what is to come.

Ford’s feature films from 1938 to 1941 generally increase in length.

1938

Four Men and a Prayer 85 minutes

Submarine Patrol 95 minutes

1939

Stagecoach 97 minutes

Young Mr Lincoln 101 minutes

Drums Along The Mohawk 103 minutes

1940

Grapes of Wrath 129 minutes

The Long Voyage Home 105 minutes

1941

Tobacco Road 84 minutes

How Green Was My Valley 118 minutes

However, since at least 1935 there had been a noticeable tendency for Ford’s features to get longer, probably in keeping with (1) a general trend for A-pictures to get longer, (2) his growing success as an A-picture director, and (3) Darryl Zanuck’s aspirations for prestige. What happens in the years between 1938 and 1941 is that the proportion of films longer than 100 minutes becomes larger (5/9).

The years from 1939 to 1941, Tag Gallagher perceptively observes, constitute “Ford’s prestige period” – which was also “very much a populist period” (165). I am going to try to address the two words, “prestige” and “populist”, at least indirectly, in most of what follows.

*****

Young Mr Lincoln is a very tempting text. It seems that every second of the film has been designed to invite appreciation and discussion; and I expect that this is one of the reasons that it slips so easily into the “classic” or “masterpiece” category, with which I ought not be much concerned here. The disc in the Ford At Fox set is labelled “The Criterion Collection” and “disc one: the film”. Disc two, one imagines (correctly), must contain documentaries and interviews and other material related to the film, all designed to extend and enhance the experience, in the way of disc twos the world over. In view of all that, it is utterly amazing that there is no commentary on disc one.

But merely imagining disc two – or, indeed, a commentary for disc one – is all right because Young Mr Lincoln itself is made to set you dreaming. It is a veil behind which vague, suggestive shapes wave. History? Mythology? Politics? A culture’s psyche – or just another figuration of desire?

There’s a big element of kitsch in this, and sound, especially music, plays a big role in the film’s kitsch effect. I think that one of the most noticeable changes in Ford’s work for this “prestige period” is in the type and the amount of time devoted to music on the soundtrack.[2] In Young Mr Lincoln the music seems insistently present from the opening titles during which “Rally ‘Round the Flag, Boys” is sung by a womens’ choir with precise upperclass diction. There follows a section in which slow sentimental strings play a folk melody, and spruced-up folk music at least tinges the rest of the score. Moreover, in the “prologue” or pre-Springfield scenes the music seems to follow its own non-narrative, descriptive, diegetic line and the sound mix features music so prominently that at times it seems almost on a level with the dialogue.

This sound design is in keeping with the series of strikingly generic images that characterises the first half hour and more of the movie. Here are some of them:

Indeed, Young Mr Lincoln is stuffed with such images, like a Thanksgiving turkey. And they are, like Thanksgiving turkey, wonderfully flavourful, filling and always just a bit too much.

*

Some disturbances – subtexts?

Tag Gallagher – who has written, as usual, well and to the point on this film – claims that “no blacks appear in its 1830s Illinois” (184). But they do, if less prominently than in earlier Ford films. There are 2 African-American men (uncredited) marching in the Independence Day Parade holding a banner for the “War of 1812 Veterans”. Their images appear directly after we see Abe (Henry Fonda) as a spectator; they are followed by Sam Boone (Francis Ford) with a jug. There is a black servant (shown in a still in Gallagher’s book) in the Clinton house when Abe comes to the soiree where he dances disastrously with Mary Todd (Marjorie Weaver). The servant’s image initially directly follows Abe’s, and he is otherwise visually associated with Abe in other shots in the sequence. The point is that these fleeting images are easy to miss, the actors uncredited, and that their comparative invisibility is of a piece with the inoffensive kitsch of the whole – in spite of their visual association with the figure of Abe. I should point out that the period during which African-American actors were heavily promoted, and specifically the period of Lincoln Perry’s ascendency, was long gone by 1939 and it was undoubtedly no longer studio policy to feature black actors in many Fox films.

Lighting is a key element of Fonda’s appearance as Abe. Lincoln’s skull-like face tends to make many of the attempts to portray him onscreen throughout the years sort of creepy, starting at least with The Birth Of A Nation, and I have often thought that the white South must have seen that image of death as Lincoln’s principal aspect. This example of the same kind of imagery comes from the first sequence of the film.

One of the most striking instances of this figuration of Lincoln occurs in conjunction with the fleeting appearances of African-Americans mentioned above, as Abe gets ready to go to the Clinton’s soiree.

There is also an intriguing use of dark expressionist tonality for certain interior images of Abe. One of those shifts in tonality climaxes a scene with Mary Todd into which the river and the future are intermixed – and might even be said to be the climax of the first, largely contextual, part of the film.

“Normal” (if expressionist) tonality:

The climax of the scene:

*

Visions and what cannot be articulated

The very first sequence sets up a pattern of simplification in a sort of bucolic prologue but then, with ominous music, winter sets in, and Abe visits Ann’s grave in the snow. He talks to her (as Judge Priest talks to his dead wife at the graveside). Does Ford believe that Abe is doing anything other than talking to himself? (Abe stands up a stick so that her spirit may influence its fall but then says, “I wonder if I could have tipped it your way just a little?”).

Both Abe and Abigail Clay (Alice Brady) want to hold on to the past. Mary Todd, who is contrasted as much with Abigail as she is with Ann Rutledge (Pauline Moore) is, on the other hand, determined to break with the past (her class and region). She is the direction in which that stick, perhaps animated by Ann’s spirit, falls.

Abe on pie judging: “So it goes: first one, then the other”. Abe and Abigail Clay recognise that there are situations in which one or another side’s winning is not the best outcome. The judgement of Solomon is mandated far more often than Abe’s first reading of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England suggests. (“By Jing, that’s all there is to it! Right and wrong!”, he exclaims). It turns but that Abe is, um, wrong about that because the law ensnares him and Abigail in a dilemma precisely about the difference between what is right and what is the law (in other words, not used in the film, what is due to God and what due to Caesar).

Abigail cannot tell Abe which of her sons did the murder. She cannot speak the words.

Abigail: I can’t. Be just like choosin’ between ’em.

Abe: “Lot of people like to see those boys hung.

Abigail: I know, but I just can’t

…

Abe: Naw, I don’t reckon you can.

It is not that she does not know (or think she knows), but that so long as she does not reveal what she knows her two sons are equally guilty and equally innocent – that is, they are in limbo, in a liminal state. What this does is merely to keep them in the state they occupy existentially between their arrest and the verdict. It does not defray the verdict: it is merely wishful. That is, it repeats the state that we leave Abe in during the pie judging. In this fiction we need never know the result of the pie judging – but we probably believe that there was finally a result. And in this fiction there must be a verdict for the trial.

Apparently Abe cannot believe that the prosecution would call Abigail Clay. Apparently Abe’s reverence for motherhood is what has betrayed him here. Ford understands this and applauds it, but remains at a distance, allowing us to be surprised by Abe’s surprise. Just as in the story of the film itself, Ford shows “the truth” rather than “what’s right”. This surely must be because judgment must involve the truth and because in the universe he makes in his films Ford can make the right and the true congruent.

Felder, the prosecutor (Donald Meek), tells Abigail she must “speak the truth”. Abigail: “I can’t” (see above). Abe: “I may not know so much of law, Mr Felder, but I know what’s right and what’s wrong”. Compare this with his first reading of Blackstone and, of course, with peasant/visionary morality – because the “peasant cinema” identified by Bertrand Tavernier seems to have coloured all of Ford’s films from this period.[3]

Gallagher wants to make a distinction between “character” and knowing what’s right and wrong – but I am not sure that the film does this. Certainly it makes a distinction between “the law”, in the sense of codified and more or less thoughtless system of “rights and wrongs”, and knowing what’s right and wrong. Abe finds he does know what’s right and wrong, and (because of this?) he is vouchsafed a vision of the truth of the matter. He sees, he imagines, what actually happened, what must have happened, in the murder; he does not deduce (much less prove) it – which is surely why he recites it all to John Palmer Cass (Ward Bond) while the later is outside the space of the court.

*

The passage from peasantry

Gallagher says “The thrust in Young Mr Lincoln is passage”, a transition from somewhere (death? life?) to somewhere else: “one world to another, youth to age, innocence to wisdom, man to monument” (195). This is liminality, a state of in-between. Cahiers du cinéma‘s inability to recognise a liminal state seriously vitiates the journal’s famous attempt at a deep political analysis of the film.[4] That is, in a liminal state all is in suspension, not yet properly formed – thus what happens in such a state does not mean what it would mean were it to happen in a non-liminal state: it is a kind of experiment or rehearsal – perhaps a kind of populism. Time is a key factor in such situations, even if history is not.

Gallagher’s summary of Lincoln: “Lincoln is a paradigm of the Fordian hero: celibate and alone, possessed of higher knowledge to mediate intolerance and proclaim a new testament, even by violence or cheating. Judge and priest, a sacrifice like Christ, he reunites a family and walks away at the end.” (198). (But of course he does not walk away from, but a little way after, the Clay family).

History acts as validation for heroes at least. As seems reasonable for a liminal state, the film shows a past that is always prefiguring the present and the future. The reason for the past seems to be to prepare for the (better?) future. Ad hoc ergo propter hoc. If this is “a hero effect”, it would seem that heroes must cast some kind of quasi-retrospective influence and that history is determined, but I think it is simply a formal convention of Ford’s kind of populist/legendary fiction. (A formal convention that packs a lot of persuasive power.)

The hero and the mob (crowd) are bound in a terrible union. If African-Americans are the invisible subject of lynching, revolution is the invisible driver of mobs. Mary Todd knows this. She calls the lynching attempt “the recent deplorable uprising” in the invitation to the dance that she sends to Abe.

Abe’s selection of jurors is based on his vision (which Gallagher might call his character). He accepts the drunken Sam Boone because of what he perceives as his honesty, just as he accepts the honest man who dislikes the Clay boys. Honesty is a stellar peasant virtue; and surely, first of all, as a kind of reassuring underlining of his heroism, Abe is a peasant or, perhaps more accurately, he comes of peasant stock. Consider his chosen musical instrument, the “Jew’s harp” and the song he plays on it (“Dixie”).

Here is some more evidence of the invisible peasant soil of this film.

Abe on Abigail in court: “Look at her. She’s just a simple, ordinary countrywoman. She can’t even write her own name.” … “I’ve seen hundreds of women just like her, workin’ in the fields, kitchens, hoverin’ over some … sick and helpless child. Women who say little but do much, who ask for nothin’ and give all.” That is, she is a common person, a peasant, of the land. (However, Alice Brady’s cultivated theatrical accent suggests that Abe’s characterisation may not be entirely accurate).

And there is Efe Turner (Eddie Collins), a Sancho Panza-like figure whom Abe leaves behind at the climax of the film when he walks up the next hill over which the Clay family has recently disappeared.

Many have suggested that Abe is walking toward his destiny, his future, when he walks up the hill. It is not at all inappropriate to point out that when Young Mr Lincoln was made the world itself was in a liminal state, awaiting a war. This too is where Abe is walking.

And if Ford’s cinema is a “peasant cinema” it is so in the same sense that Molière’s plays are “peasant theatre”. Certain aspects of what the author believes to be peasant morality are valorised in them, but the author himself is far from adopting a peasant’s point of view. In this case I believe that the author and the main character share a certain distance from what they seem to be endorsing most wholeheartedly.

*

Fonda’s performance, Abe’s performance

Abe is a performer. Not only does he tell stories and crack jokes, he also plays a musical instrument of sorts. The line between Fonda, the actor performing Abe, and Abe, the actant performing Abe, gets blurred, just as it does in the Will Rogers movies. At one point, Gallagher says something about Fonda’s grace at the soiree (185), and by this he must mean a grace that appears in spite of what is called for by the story – that is a grace that belongs to Fonda, not to Abe – for one of the points of the scene is that Abe is not graceful on the dance floor.

Fonda performs in the court, often very much like Will Rogers in Judge Priest. Stephen Douglas (Milburn Stone) explicitly acknowledges this quality of Lincoln’s (“Mr Lincoln is a great story-teller. Like all such actors, he revels in boisterous applause.”). Consider these stills in the light of the simultaneous performances of Abe, Fonda – and Ford.

*

Honi soit qui mal y pense

*

Quasi-addendum

This is not a photograph of Henry Fonda playing Abe Lincoln. It is a (rather peculiar) photograph of the man who owned Ford’s Theatre, where Lincoln was shot in 1865. I read the following paragraphs on this man thinking of Young Mr Lincoln and The Prisoner of Shark Island, and John Ford of Maine as well as John Ford of Maryland, and, of course, of the figure of Abraham Lincoln.

[John Thompson] Ford was the manager of this highly successful theatre [Ford’s Theatre] at the time of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. He was a good friend of Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth, a famous actor. Ford drew further suspicion upon himself by being in Richmond, Virginia, at the time of the assassination on 14 April 1865. Up until April 2, 1865, Richmond had been the capital of the just defeated Confederate States of America and a center of anti-Lincoln conspiracies.|

An order was issued for Ford’s arrest and, on April 18, Ford was arrested at his Baltimore home which he had reached in the interim. His brothers James and Harry Clay Ford were thrown into prison along with him. John Ford complained of the effect his incarceration would have on his business and family, and offered to help with the investigation, but Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton made no reply to his two letters. After thirty-nine days, the brothers were finally fully exonerated and set free since there was no evidence of their complicity in the crime. The theater was seized by the government and Ford was paid $100,000 for it by Congress. Due to the treatment accorded to him following the assassination, Ford remained bitter toward the United States Government for decades. (Wikipedia)

I believe that it is not likely that John Ford, the person with whom I once exchanged some sentences bearing on how one reads the past, would have considered the similarity of his name and the name of the owner of Ford’s Theatre mere coincidence.

*****

[Drums Along The Mohawk (1939)]

Joseph McBride considers the film simplistic and racist. In a short article on Ford which appeared in the same issue of Présence du cinéma as Bertrand Tavernier’s piece on Ford’s “peasant cinema”, Alain Ferrari, interestingly, compares Ford’s treatment of the story to a nightmare.[5]

There is a commentary on the disc, a very interesting one. It is in the form of a dialogue between Julie Kirgo and Nick Redman, whose work in history and film history has mainly resulted in films themselves. Both were involved with Becoming John Ford, the documentary packaged with the Ford At Fox set. Kirgo is credited as the writer of that film, as well as an associate producer and Redman as the director and a producer.

Colour is, in point of fact, quite important in the impression that this film makes.

Significance of “artistic” cinematography during this “populist prestige” period of Ford’s work. Long shots and extra long shots in Drums Along the Mohawk. This seems like a film of long shots where the eye is constantly being drawn to the centre and the back of the image, away toward the horizon. So much seems to be happening behind or around those in the foreground or middle distance.

The silhouettes in the running sequence are now iconic.

Gallagher says this is Ford’s “least expressionistic [film] since talkies began” (199). But there is some striking “expressionism” in the film, as evidenced above, and in the stills below.

These last two shots also suggests the film’s affective use of thresholds (including stairs, vehicles and other means of transmission), sites of turbulent emotion, of upset, passage. Very often the long shots of the film also depict passage – not only in images of roads, actual or suggested, or in movement within the frame, but simply in the distance, temporal and physical and narrative, between foreground and background: a distance the film is sooner or later bound to span. In terms I have used before, this is part of a strategy of folding as distinct from cutting, as images overlay one another rather than are separated from one another. These long shots put viewers in the position of looking in depth and having to look twice.

Gallagher: “[Drums Along the Mohawk] sketches a gloomy series of events undergone by pioneer settlers in New York’s Mohawk Valley, 1776-1781. The land is work; Indians attack periodically; farmhouses and crops are burnt: children are born, men march off to fight the British and die. But the land is virgin, the people young, the air suffused with freshness, the gloom something to be brushed aside” (198). This outline omits that the hostile Indians are shown from the first to be directed by a British agitator (John Carradine). Lana’s (Claudette Colbert) fear is apparent in the very first shot of the film, and has its culmination when she kills the Indian who menaces the group she is protecting in one of the climactic scenes. The gloom of war/destruction/fire is never brushed aside: it suffuses the entire film – a nightmare, as Ferrari says.

But, most telling of all in the context of the films surveyed in this section, the community always returns to the land it has temporarily left. If we are being shown a community in transition, the goal of their journey is never in any doubt. It is not strictly speaking correct to call the characters in this film “peasants” when they are in context members of aspirant rural middle class (farmers, artisans, merchants), yet at the same time they are clearly intended to embody virtues commonly attributed to peasants: tenacity, hard work, a feeling for the land, simple morality, the wisdom of experience, lusty exuberance. Peasant references abound: the cow attached to the wagon that takes Gil (Henry Fonda) and Lana to the country, farms, crops, “documentary” coverage of certain work practices, the desire for land of one’s own. Lana and Gil Martin seem like younger versions of the Adam and Abigail Clay we see in the beginning of Young Mr Lincoln.

The Big Issue: History (Gallagher cites it, and the commentary concentrates on it) vs Spectacle (production design, etc.). The commentary actually treats the film as though it intended to faithfully represent the events of (some kind of) history: the commentators talk mostly about the actual events, people, etc. upon which the fiction is “based” – or, as I would prefer, out of which it grew.

Kirgo, for example, remarks at one point of the characters in the film, “These are people who are not yet Americans”. But these characters are not “people” at all, never were and never will be – and surely the point of the film is precisely that they are “Americans” even if they do not know it. The actors (the actual people) on the screen come from various countries. And it is also the case that it is virtually impossible to say when the characters/people Kirgo intends to refer to – the real people of the time and place fictionalised in the film – did become Americans: whether, for example, the motives for their rebellion made them Americans before the fact or whether Indians and African-Americans were made Americans in any significant way by the success of the revolution.

The point is not that Kirgo has made a silly remark but that the very “historical reality” of such an unremarkable, commonplace perception as the relation of “people” in general to “Americans” in particular resembles fiction far more than it does anything that one usually thinks of as history.

An apparent digression is, it seems to me, actually a telling response to precisely the issue of what is history and what fiction that the film overtly presents:

Redman: That is one of the true tragedies of history, isn’t it? That everyone in the end breaks their …

Kirgo: Breaks their solemn promises and treaties. Yes. Absolutely.

That is, history always betrays the fictions made from it, just as first Gil, then the man of God (Arthur Shields), and finally Lana, kills. Or just as hot water, like so much else in this film, is deployed twice: first for birth, about which Adam (Ward Bond) remarks, “I don’t know why we gotta have so much hot water when babies are born anyhow”, and then in the climactic battle when the women use it to save Adam and others briefly from the Indian’s final onslaught.

The explicit thematic of the origins of the United States surely has much to do with the film’s status as a middlebrow “classic”. The commentary explicitly discusses “patriotism” and offers the telling definition: “what your country stands for” – but this, of course, is precisely what history in the sense of actual events and people cannot show. Only a fiction can show what a country stands for because what a country stands for is a matter of the interpretation of events and personalities, not What Really Happened but What It Really Meant.

Gallagher: “The film’s siege is fictitious”. In a significant sense, this is the very point of the film and of the book from which it was taken (a historical fiction aimed at teenagers as much as at adults)[6] . Indeed, the film is very, very upfront about its artifice while emphasising “documentary” passages of work and other aspects of everyday life. The production design and sheer beauty of the film is deliberately enhanced. This is “expressionism” too, in the broader sense of deliberate and noticeable (visual) artifice that intrudes on a “realistic” experience.

Consider the evocation of war through dialogue and complete suppression of sounds of pain in the nursing scene. Initially the ambient sound level is rather high, as Gil is brought into the room along with other soldiers and there is much rustling and sound of movement (but no words, groans, or other oral sounds). But as the camera moves in, these background sounds disappear and only Fonda’s and Colbert’s voices are be heard. This effect is crucial and must have been achieved by the sound crew working in pre-planned synchronisation with the camera crew while the scene was being shot.

Zanuck had been growing progressively more frantic as the date for the troupe’s return from Utah drew near and Ford, already over budget and behind schedule, made no preparations for this huge battle — it had been scheduled for three weeks of shooting. He badgered Ford daily with telegrams. Then one day Ford replied: they were caught up, within budget, and the battle had been filmed that morning. What had happened was that Ford, out of a clear blue sky, had turned to Henry Fonda (Gil): “Henry, I have to shoot a battle scene that I don’t want. I had a better idea today. You’ve studied the script and your role, you probably know more about the battle than I do. Sit down and lean against this wall.” With the camera aimed at Fonda, Ford fired a series of questions: “So, Henry, how did the battle begin?” And Fonda replied, making up an account. “And Peter? What happened to Peter?” asked Ford; or, “What was it like to have killed that man, after seeing John die?” And Fonda went on improvising, giving a virtual psychoanalysis of the battle. “Cut,” called Ford, and told the editors: “Cut out my questions and use it as it is.” One long take.(280)

This is Gallagher’s summary of Robert Parrish’s account as published in the French journal, Présence du cinéma[7] .

Satisfying as Parrish’s anecdote is, what happens on the screen casts some doubt on its accuracy as history. Ford does not appear to be feeding questions to Fonda off camera; for one thing Colbert is quietly but franticly talking to Fonda at every break in his monologue. Still, the scene is “one long take”, and a virtuoso take at that, broken only at one point by cutaways to three short shots showing another part of the house where General Herkimer’s leg is amputated to the accompaniment of hushed dialogue and a soft grunt from the General (Roger Imhof).

The on disc commentary by Kirgo tells a slightly different story about the circumstances of the scene and expands on its virtuosity.

The battle was a scene [in the script], and Ford had actually prepared to shoot the battle scene. But evidently, possibly at one of the campfire events that he would habitually have on location, he and Henry Fonda were talking about the scene and Henry Fonda began to extemporanise [sic] about the battle, what it must have been like, what Gil must have seen. And Ford said, “I’m not shooting the battle; let’s do this: you tell the story of the battle”. It’s an amazingly effective scene, as we’ll see. This I think is such brilliant staging. You are focussed on Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert as she tries to dress his wound and he tells the story of the battle, but meanwhile there is all kinds of action going on around them. She is busy with trying to dress his wounds, make him more comfortable: save his life. And meanwhile there are other women in the background doing the same for other soldiers. And it just … and there’s the firelight … and he is telling this horrific story of the battle, which comes very much alive; and he tells it in a way that is very characteristically Fondian, if I could use that word (if it is a word). He is not screaming it out; he is not being all histrionic about it. He is just telling the story.

It would seem that Fonda ought to be given credit for the harrowing story as well as its performance. It is one of the most effective anti-war scenes I know, which does not mean that Ford was anti-war, only that he was, like Fonda, a vehicle for whatever made the drama work.

False/true mother: the active/activist widow McKlennan (Edna May Oliver).

Although the film begins with Lana’s point of view, it gradually broadens to include, first, the couple’s point of view, and ultimately that of the entire community.

Charges of “racism” in this film seem to derive from the portrayal of the savage behaviour of the hostile Indians and the apparently patronising portrayal of Blue Black (Chief John Big Tree). However, this still goes a long way towards questioning such a swift judgement.

Honi soit qui mal y pense.

Blue Black is announcing that he has killed the British villain who was behind the Indian attacks. Thanks to Nick Redman and Julie Kirgo for confirming my perception of the positive nature of this image in their commentary. What they do not say and I will is that it is really hard to think of the man who directed this shot, which is a doppelganger image of himself, as a benighted racist. I bet that is Ford’s own eye-patch.

Although I have used Kirgo and Redman as straw figures to stand for a school of criticism I clearly think is misdirected I want to stress that the commentary track they have done is interesting, sensitive and well-informed. It addresses issues which most people will want to have addressed, which is not a bad thing, and it is intelligent and observant – which has not been my experience of most commentary tracks. You ought to look at the film at least once with their commentary.

*****

The two-sided disc which is devoted to The Grapes of Wrath contains a striking digital restoration that does visibly improve on the restoration of the film material as well as a commentary track. The B-side of the disc includes a 45 minute account of Darryl Zanuck’s career which provides a Zanuck context for the Ford/Fox films from Steamboat round the Bend to What Price Glory.

*

Communism

The commentary on The Grapes of Wrath is by Joseph McBride, who has been cited in these pages several times already, and Susan Shillinglaw, a professor of English who is one of the leading scholars of John Steinbeck and his writing.

Their commentary is about film/novel relations (in case you did not know, the book and the film are quite close) and about reportage – that is, how both the book and the film represent “the reality” of their topic. In this latter aspect it is much like the Drums Along the Mohawk commentary. This is a particular critical practice and it is not one that I follow most of the time. In this case it rather has the effect of making Ford’s film into a copy of a copy (a film of a book about a reality), which is unfortunate. And, despite their praise for Ford’s work, neither of the commentators deals with the direction of any scene in detail, as Julie Kirgo does during Drums Along the Mohawk. At the same time, as I tried to suggest in what I wrote about Drums Along the Mohawk, a commentary which treats a film as a medium for representing something else, like history or reality, can add considerable interest to what you are looking at – and this one does that even better than Kirgo and Redman. For example, there is a difference of opinion between Shillinglaw and McBride on Steinbeck’s later “conservatism”, which takes up rather a lot of time, but is extremely interesting for the tension between the commentators that it generates, and because “anti-communism” figures so strongly in the later political attitudes of both Ford and Steinbeck. Although neither McBride nor Shillinglaw says so, the point at issue comes down to the circumstance that there is actually not now, nor was there in the thirties, a consensus on what constitutes “left” and “right”, “liberal” and “conservative”, much less where “communism” figures in the debate.

The issue is not so irrelevant as it may at first seem today. Everyone these days agrees that The Grapes of Wrath is unusual for a Hollywood movie in that it is unapologetically tendentious and leftwing. But everyone also agrees that not all tendentiously left art produced in the US during the thirties was “communist” in the sense that it was sponsored or directed by the international Communist movement. The latter half of the thirties was a period in which the understanding of what constituted “communist” art broadened considerably, as a result of the Communist International’s 1934 Popular Front initiative, which advocated cooperation with any group opposed to fascism. John Steinbeck, and Erskine Caldwell (author of Tobacco Road) were among the American novelists whose work was identified with the Popular Front.

It was surprising even at the time that Ford’s film for Twentieth-Century Fox preserved so much of the tendentiousness (or just preachiness) of the novel. But no one nowadays thinks that John Steinbeck or John Ford (much less Darryl Zanuck) were taking directions from the Communist Party, and I don’t think that was the case either. What interests me is that the tendentiousness in the form and substance of the film are, it seems to me, pretty close to what can be found in Soviet – that is, definitely communist – films in the thirties.

Why would that be the case? First let me sketch the peasant connection for Soviet film.

I have already had occasion to mention Sergei Eisenstein’s sojourn in the Americas (1930-32). Eisenstein came to Hollywood the year after he had completed The Old and the New (1929) and the project which occupied him most in the years immediately after his return to the USSR was the unreleased Bezhin Meadow. Both of these films were about peasant life in the Soviet Union. The “Mexican film” on which Eisenstein worked during the latter part of his sojourn was about the relation of the Mexican peasantry to the impulse to revolution in Mexico. (To round out the connection between Eisenstein and Ford’s “cycle” of peasant films, in 1945 the Soviet director and theorist wrote an extremely perceptive and sympathetic essay on Young Mr Lincoln which discusses the figure of Abe in that film in terms of certain peasant-like attributes – see Note 3 below).

The peasant subjects of Eisenstein’s films were by no means unusual in the Soviet cinema of the thirties. The peasantry was an explicit concern of Soviet policy in the twenties and thirties, and Soviet films on the topic were overtly tendentious. However, for the Soviet government of the period the peasant class was the product of a feudal regime; and peasants, unlike workers, tended to be depicted as inherently violent and small-minded, as well as too attached to private ownership. The villains of such movies were kulaks, “rich peasants”, who shared the ugly characteristics of peasants in general to which were added greed and lust, as well as the despotic tendencies of the bourgeoisie. Peasant heroes, on the other hand, were visionaries (not unlike Tom Joad) whose ideas came to transcend their historically determined class situation, and who often found themselves at odds with that class even when their efforts were directed towards its betterment. A lot of this seems to be floating around in both the book and the movie of The Grapes of Wrath.

Consider also Peter Kenez’s summary and extension of Katerina Clark’s analysis of the Soviet novel:

…a socialist realist novel is always a Bildungsroman, that is, it is about the acquisition of consciousness. In the process of fulfilling a task, the hero, under the tutelage of a seasoned Party worker, acquires an increased understanding of himself, the world around him, the tasks of building communism, class struggle and the need for vigilance. Indeed, the same masterplot can be found in films …

Socialist realist films included three stock figures with depressing regularity: the Party leader, the simple person, and the enemy. The Party leader was almost always male, ascetic … unencumbered by a family or love affairs. The simple person could be male or female … sexual relations were always chaste … the enemy, whose function was to wreck and destroy what the Communists were building was always a male … [8]

If Clark’s and Kenez’s analyses suggest the simplicity of folk tales, it is not a coincidence. “Socialist realism” was explicitly linked to the virtues of folk traditions. Moreover, the “documentary” elements of both versions of The Grapes of Wrath were part of a conscious attempt to create an accurate figure of the “the people” (the folk) in words and images, and to be guided by that figure in determining how to think and act. The “natural” and “innocent” qualities of such a figure were a distillation of the “natural” and “innocent” qualities of traditional folkloric peasant figures, just as less admirable qualities of traditional peasant figures were represented in Soviet films of the period, all in the name of a fundamentally accurate documentation of reality that transcended mere reproduction. And the emphasis on money, prices, wages, work and ownership as mechanisms of control and liberation critically affecting the lives of rural characters were equally derived from and dependent on the desire to depict things “as they really are”.

Soviet films from the thirties in which peasant ideas and culture play a key role include Earth (Dovshenko 1930), Chapayev (1934), Peasants (Ermler 1935), Happiness (Medvedkin 1935), and The Childhood of Maxim Gorky (Donskoi 1938).

To complicate matters, films like Chapayev strongly evoke Ford’s work. There is obviously a kinship between what Ford appears to be doing by valorising “the common man” in stories that depend upon conventional characters and conventional narrative structures and what Soviet film makers were doing in “socialist realist” films like Chapayev and The Childhood of Maxim Gorky. I believe that Ford’s films influenced Soviet socialist realist films as well as the other way around.

However, the elements of Soviet style and theme in/of the film and the book of The Grapes of Wrath make an awkward fit with the shifting alliances of the USSR during the period between the book’s publication (April 1939)) and the film’s release (January 1940). In August of 1939 the Soviet Union signed a treaty of non-aggression with Nazi Germany, effectively bringing the Popular Front against fascism to an end.[9] This meant that the film premiered in an atmosphere in which the non-communist left tended to feel it had been used and betrayed by the Comintern. The positive references to “reds” in the book and film now pointed, however distantly, to an ally of Germany, which had invaded Poland in September, 1939.

This can’t have been a comfortable position for either Steinbeck or Ford, who appeared at the very least to have used forms and ideas prescribed by the Soviet Union to depict injustice and oppression in the Unites States – and surely this circumstance accounts in some measure for the strong anti-communist stand both were to take after the war. In Ford’s case, his own somewhat prescient military activities suggest he may have deliberately and consciously taken an (unvoiced and private) stand against the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

In 1939, according to Gallagher, Ford began training a group that would become his Office of Strategic Services unit during WW2: the Field Photographic Branch (234-235). That is, in 1939 he was anticipating a war in which he wanted to play a part, not supporting any sort of appeasement urged by communists or anyone else. In September 1941, after the German invasion of the Soviet Union but before Pearl Harbour, the unit was ordered to Washington where it was formally adopted into “Wild Bill” Donovan’s spying operation; and it remained a part of the OSS throughout the war. It intrigues me that Ford was in the OSS, in a sense acting as Tom Joad says he will act when he heads underground in the climax of The Grapes of Wrath; and I have to believe that Ford’s service in the OSS had something to do with the extremely light treatment he received at the hands of the House Un-American Activities Committee during its notorious postwar Hollywood witch hunt.

But the most instructive lesson I take from the overtly Soviet content and style of the film of The Grapes of Wrath is that HUAC was not actually interested in whether Hollywood had been serving up communism in its movies at all. If it had been it would have condemned Ford (and Zanuck), among others, for The Grapes of Wrath, among others. Instead it was interested in catching communists no matter what they had, or had not, done in the movies. HUAC never for a moment really believed that “communist propaganda” was potent, but it did believe that communist people were bad in some kind of indefinable way. And, I think, this is the belief that Ford and Steinbeck came to share as well. They knew that they had not (permanently) caught any disease from their relations with communism, but they were convinced that others must have.

Which is to say, Ford and Steinbeck felt they knew better, were better, than others; they had been inoculated to recognise a truth that others could not. In that of course, they recall such figures as Abraham Lincoln and Tom Joad, representatives of the common people who are not common people themselves. It is not outrageous to think of such an attitude as rightwing – meaning in this instance quasi-fascist – populism. It has its Stalinist counterpart in Soviet culture, and is expressed forcefully in the work of the best known Soviet directors of the thirties.

*

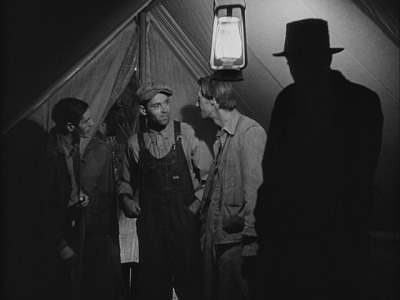

The Shadow

The shadow of communism is actually represented in the film, although neither McBride nor Shillinglaw mentions it when it appears:

We never see this shadow’s face nor hear it speak. It is there in the foreground during Tom’s meeting with the strikers which precedes Casy’s murder.

Ford – or the film – does not ignore the implications of this figure, as this still of Tom’s shadow from the sequence of his departure suggests:

I would be more justified in calling this repeated figure “the shadow of communism”, if only anyone had cited it as evidence of Ford’s uneasiness with the leftist tendencies in the film. As it is, the shadow may only be a way of fore … um … shadowing what is to become of Tom. Perhaps it ought to be called “the shadow militant” or again, “the fugitive”.

*

American radicalism

Ford has said that he was interested in The Grapes of Wrath partly because the plight of the Okies reminded him of the Irish. McBride, in his commentary, draws a parallel between the Okies and African-Americans forced to sit in the special “coloured” sections of movie theatres, and Shillinglaw then extends the parallel to the migrant Mexican farm workers in the past and present southwestern United States. This series of equivalences suggests a different radical line, one more surely linked to the radical cultures of the United States than to the Soviet Union, where minority groups and ethnic differences did not play a great part in defining Soviet communism.

The Grapes of Wrath, like the Soviet films mentioned above, is explicitly concerned with the movement of peasants, rural farmers, to (or towards) a different status. However, in The Grapes of Wrath those who most resemble traditional agrarian peasants in their attachment to the land are literally left behind in that movement, and those who leave the land seem destined to live in a state of perpetual migration.

Muley (Eddie Quinlan), who appears when Tom Joad and Casy (John Carradine) are looking for Tom’s father, simply will not leave the area which contains his farm.

Muley and the land:

Grampa Joad (Charlie Grapewin) must be sedated with alcohol to get him to leave.

Grampa and the land:

Later he dies by the side of the road grasping another handful of dirt. The association of the gesture of handling the soil with the idea of depletion is not found so often in Soviet films as it is in American culture of the thirties, when the “dustbowl” was as prominent a symbol of the Depression as the stock market crash.

In The Cultural Front, Michael Denning uses The Grapes of Wrath as an example of one of the most effective and lasting popular “myths” created by the American left in the thirties.[10]

[T]he best-known Popular Front genre is probably the “grapes of wrath,” the narrative of the migrant agricultural workers in California. Indeed, the “Okie exodus,” the tale of southwestern farmers traveling out of the drought-ridden Dust Bowl of Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, and Missouri to California remains one of the most striking examples of Popular Front narrative becoming part of American mass culture . . . The story came to national attention with The Grapes of Wrath: John Steinbeck’s novel was a national best seller in the spring and summer of 1939 and was made into a film by Twentieth Century Fox, opening in January 1940. (259)

Denning traces the lineage of this particular narrative from historical events beginning in 1933 through Dorothea Lange’s photographs, which were first published in 1935, to Pare Lorentz’s The Plow that Broke the Plains (1936), to the publication of Steinbeck’s novel in 1939 and the film in 1940 – each a groundbreaking moment in its category: labor history, committed photography, government funded documentary, American literature, tendentious Hollywood feature film (260-261).

Lange’s most famous photograph of the period is the one known as “Migrant mother”. Its actual subject, Florence Owens Thompson, was interviewed by Bill Ganzel for his book, Dust Bowl Descent. Thompson migrated to California more than a decade before Lange took her picture, and spent that time very much in the world depicted by The Grapes of Wrath.

I generally picked around 450, 500 [pounds of cotton every day]. I didn’t even weigh a hundred pounds. I lived down there in Shafter, and I’d leave home before daylight and come in after dark. We just existed. Anyway, we lived. We survived, let’s put it that way. I walked from what they called a Hoover campground right there at the bridge [in Bakersfield]. I walked from there to way down on First Street and worked at a penny a dish down there for 50 cents a day and the leftovers. Yeah, they give me what was left over to take home with me. Sometimes, I’d carry home two water buckets full. Well, [in 1936] we started from L.A. to Watsonville. And the timing chain broke on my car. And I had a guy put it into this pea camp in Nipomo. I started to cook dinner for my kids, and all the little kids around the camp came in. “Can I have a bite? Can I have a bite?” And they was hungry, them people was. And I got my car fixed, and I was just getting ready to pull out when she [Dorothea Lange] come back and snapped my picture.[11] (183)

I am not sure whether the coincidence between Thompson’s recalled experience and that incident where Ma Joad feeds the kids in The Grapes Of Wrath is well known. Lange apparently did not ask Thompson about herself, but may have observed the incident. Thompson, who was quite annoyed with Lange for exploiting her image, does not seem to have said anything about Steinbeck or about the movie, both of which use the incident. It is even possible, I suppose, that her recollection of what happened has its origin in one or another of those texts. The incident itself is not so much part of history as of myth.

Denning offers an explanation of the mythic function of the Okie migration story.

The ideological crisis of the depression was in part a crisis of narrative, an inability to imagine what had happened and what would happen next. The apocalyptic dreams of revolution of the young communists and their recurring appeals to the Soviet experiment were dramatic instances of the search for a powerful narrative resolution: the stories of martyrdom and tragic defeat in Gastonia, Scottsboro, and Harlan demanded some way out. The way out was migration, and the representation of mass migration became one of the fundamental forms of the Popular Front. Many of the most powerful works of art of the cultural front are migration stories . . . (264)

. . . the migration as exodus came to be one of the grand narratives, the tall tales, of the mid-century United States. (264)

The story of the Okie exodus also achieved its great popular success because it fused contrary populist rhetorics in a remarkable and unstable amalgam, not unlike the New Deal itself (265)

I would say that populism itself is fashioned out of a fusion of dichotomous rhetorics and that it is characteristic of popular artworks to make themselves available for a number of conflicting interpretations: the Okie story is not notable in that regard. What may be notable is the way in which contrary rhetorics in this instance found expression in Steinbeck’s novel as varied registers of discourse, or modes if you will.

John Dos Passos’ USA Trilogy (1930-36), at once his most leftwing and most avant-garde work, was published in full in 1938. This was followed in 1939 by Adventures of a Young Man, the first volume of District of Columbia (1939-1949; 1952), which uses many of the same avant-garde techniques to trace the author’s growing disillusion with both the communist and the liberal left (his ultimate political position is perhaps best understood as libertarian). Dos Passos’ non-linear narrative had a direct influence on Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. At the time of the film’s production and release, Dos Passos was still considered a leftwing author in good standing, but he was also credited with developing a specifically “American” avant-garde prose style in which non-narrative “documentary” elements were mixed with recognisably American idioms and “advanced” elite literary strategies, with an effect not unlike that of the collective improvisation of New Orleans jazz. Denning directs our attention to this stylistic practice in a summary of Edward Berry Burgum’s reading of the book in 1947.

The success of The Grapes of Wrath, Burgum argues, lay in its stylistic blend: “hardly any style practiced today is missing from it,” from those of Dos Passos, Joyce, and Hemingway, to those of Gone with the Wind and the Saturday Evening Post. Creating a kind of stylistic Popular Front, “its appeal was directed to virtually every level of taste in the book-reading public.” Thus, the Popular Front laborism embodied in the union organizing of Preacher Casy was only one aspect of the narratives of the Okie exodus; it combined uneasily with a conservative vitalism that saw the depression and class struggle in terms of natural history, with a New Deal technocracy that celebrated the state, and with a racial populism that heroized the “plain people.” The tensions between these rhetorics of “the people” are inscribed in the cultural politics of the moment and the aesthetic forms of the works themselves. (265)

I am interested in Burgum and Denning’s claims about the book because of the way in which they at least partly intersect with Gallagher’s perception of Ford’s use of different, sometimes conflicting modes within the same film (and with my slightly different idea that this sort of thing has its roots in the baggy novels of the nineteenth century). What I find intriguing in this instance is how the film of The Grapes of Wrath seems more like a stylistic unity than the novel does and, indeed, from what one might expect from Ford himself. I put this down to Nunnally Johnson’s screenplay, which Ford apparently admired, and Greg Toland’s adaptation of Lange’s photography – which achieves the effect of making a “documentary” style that was explicitly intended as political and avant-garde into an acceptable branch of the Hollywood mainstream.

Jean Mitry considers the film a “masterpiece”, but spends much of his time discussing what is wrong with it formally, which turns out to be that it has too many boring, repetitive passages. Gallagher is far, far more interesting than Mitry on the film as a whole, but agrees with him on its formal deficiencies almost point for point. “The mood is too restricted,” he writes, “too repetitive, too seldom varied. The story itself seems to go on and on, episodically. And prolixity and monomania dominate other aspects of Ford’s style” (205).

As it happens, according to Shllinglaw, Steinbeck wanted the book to be slow; he even wrote it slowly (for him). And it is also the case that the book is written in a monotone, is repetitive: both prolix and monomaniacal. These are formal choices that Steinbeck made in part in order to place what he was writing in the vanguard of the writing of his day, that is, to draw attention to its writing. Nowadays one might argue that these formal choices help to emphasise the film’s political tendentiousness in the manner of Bertolt Brecht’s plays.[12] By slowing the pace, room is left for viewers to react and think about their reaction, room is left for characters to make tendentious speeches, room is left for questions. It is interesting that Gallagher does not allow for the possibility that the film too may be rather avant-garde, an art film rather than an entertainment film, a formal experiment. In precisely those elements that he and Mitry criticise. The Grapes of Wrath most resembles and perhaps even foreshadows the political and formal cinematic avant-garde of the eighties and much that is still considered radical these days.

Personally I was surprised to find it so riveting after so many years. I went through a period of not liking it because of its “Zanuck” ending (and, I guess, simply ignoring the rest of it), but that is well and truly over now.

*

John Carradine

John Carradine is mighty impressive as (John) Casy in this movie – more impressive I would say than in anything else in which I have seen him. Moreover, he seems to me to be a perfect visual incarnation of the figure of an American wanderer.

Ford and almost everyone else usually used Carradine as an iconic melodramatic villain (see Drums Along the Mohawk above). But these stills show another, nobler, possibility; and the second still illustrates a certain annoyingly smug American “folk” expression that reminds me of Pete Seeger. (Which came first, do you suppose?)

Another person Ford never could intimidate was John Carradine. The actor was terribly absent-minded and was forever messing things up. Few things made Ford more furious; over and over he would fly into a rage, and go on and on calling Carradine a god-damned stupid s.o.b. and every name he could think of. It did no good. Carradine would watch him with an indulgent smile and when Ford had finished would come over, pat him on the shoulder, and say, “You’re o.k., John,” and walk away. And Ford would be almost sputtering, because there was no way he could get under Carradine’s skin. (Gallagher 135)

I really should say something about how very good Henry Fonda is in all three of these Ford-Fox films. Seeing them one after another points up how well he has handled each character.

*

Endings

Tom Joad moves from his rural base (and his unseen violent, criminal, past) to fully-fledged consciousness and support of the (unionised) working class; Ma Joad comes to accept her family’s wandering and to hope for a time when they will undertake a new kind of life. This latter reconciliation with the tide of history doesn’t really happen in the Soviet films, where collectivisation is the issue. That is, the history/social upheaval that The Grapes of Wrath purports to illuminate is rather more complicated than what is depicted in most Soviet films concentrating on the peasantry.

According to the McBride-Shillinglaw commentary most of the dialogue is straight from the novel. Nunnally Johnson apparently structured the novel into a screenplay. He condensed 400 pages to about 2 hours; he integrated material from the more general inter-chapters into the main narrative; and (signficantly) he took Steinbeck’s movement from Hooverville to Government Camp to the Picking Camp and made a more optimistic trajectory (Hooverville – Picking Camp – Government Camp).[13] All of this is an impressive achievement. However, Johnson’s screenplay also seems to have suppressed the novel’s most overt avant garde qualities, turning it into the kind of narration that a Hollywood studio would find compatible.

One of the issues that the film raises for critics is how it ought to end. Some say that it ought to finish with Tom leaving the family, intending to vanish into the radical underground – not unlike the end of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (LeRoy, 1931). Others are content, as Ford himself professed to be, with the ending that appeared on the US release – which is accepted as the way Darryl Zanuck wanted the picture to end.

For some then, the dramatic and moral climax of the film occurs when Tom tells Ma that he is leaving to go underground. Here is what Henry Fonda, clearly aware of the significance of that scene, told Lindsay Anderson about how Ford handled it.

Jane and I would rehearse the scene – there was never any dialogue, or if there was, it was just a whispered ‘Come on Ma’, or something like that. Once we got to the bench, Ford would cut rehearsal … Jane and I never got to do the scene. We didn’t even run it together sitting on the floor. But I knew her well enough, we both knew that we knew the lines, we were aware we had a good scene to play, we wanted to say ‘Hey fellas, let’s do it.’ Now I feel, and I’ve felt ever since, that Ford knew this was building up in us. And when he finally was ready to go and everybody else was ready, and there was not going to be any mistake to make us do it the second time, he said ‘Okay, roll ’em.’ And both Jane and I were so charged with the scene we knew we had – I’ve never talked to Jane about it, before or since, but I’m sure she felt the same way – that when we did get into it, the emotions all came up so that we had to hold them back. If they had all come pouring out it would have been embarrassing and no one would have wanted to watch, but both of us had the emotion there charging our voices, and I’m sure our faces, but we were holding it back so it didn’t come pouring out, and as a result we got that scene.[14]

It seems to be accepted that the last shot of the ending Ford filmed was:

Apparently he knew that there was more to shoot but left Zanuck (or anyone else) to do it. Apparently he trusted Zanuck to do things right. It is said that Zanuck “directed” the new ending, which features a long monologue by Ma about the resilience of the people, but I see no particular reason to make a big deal of that. Zanuck had any number of people capable of doing what was needed – especially with Gregg Toland behind the camera – his supervision was all that was required. Just a few years later Robert Montgomery would repeat the exercise of finishing a John Ford film with no discernible difference in quality or style (They Were Expendable, 1946). Montgomery, with some modesty, claimed it was because the crew knew exactly what Ford would have done and just did it.

Still, I like to wonder why Ford left the set with the film unfinished. It does not seem like him. (Watch out, we are going off to cloud-cuckoo land again). Perhaps he had actually finished the film. Mitry reports having seen an ending that matches very well with the one in Steinbeck’s book.

. . . Ma states her faith in the power of the people which can never be defeated. We find the family later in a barn where they have chosen to set up house. They are working on the cotton harvest [cueillette]. Rosasharn [Dorris Bowden], after having given birth to a stillborn child, takes in [recueille] an old man dying of hunger and breastfeeds him to revitalise him.[15]

A cautionary tale for all critics. (Lindsay Anderson, fn, 247)[16]

I suspect that the “cautionary” note in this “tale” is, “Don’t sleep on the job”. Mitry’s concern for the boring, repetitive style of the film sets some alarm bells softly ringing in my head, for I have fallen asleep at the movies and sometimes blamed what I saw in my dreams on what was on the screen. Could he have dreamed it? Certainly no one else seems to have seen such an ending.

There is a footnote to Mitry’s account:

All of this last part has been suppressed in the French version which finishes with Tom’s departure. The ending itself (the barn) has been suppressed in nearly all the European versions (we [sic] saw it in Switzerland in 1945)… [17]

No one seems to think it significant that there are three versions of the film in Mitry’s account (French, European, Swiss). The “French” version finishes with what has sometimes been called “Ford’s ending”, giving that ending a kind of cachet of authenticity (“it really was released – in France”). On the other hand, that more militant ending might have been deliberately created from the longer “European” prints by resistance militants for propaganda purposes (or supplied to such groups by the OSS via Major John Ford). The “European” version would seem to be identical to the US release version. The “Swiss” version would contain more material than either of the other versions and would be the only evidence that any material beyond the US release version was ever shot.[18] Perhaps I ought to point out that the reason Mitry does not go into this sort of thing is that in Europe having various versions of films floating around, edited to fit the censorship criteria of various nations, was more or less commonplace. This is also why Mitry would presume, as he does, that the version containing the most footage would correspond to the earliest US release.

Nunnally Johnson to Lindsay Anderson:

The picture ended with the Joads on their way to another rumour of a few days work, and his [sic] last words, as I remember them, were when Ma said, ‘We’re the people.’ No such ending as the one the Frenchman described was ever shot or even considered. (247)[19]

The main text of Johnson’s letter insists on the priority of his script, and we will discuss that in some detail during the review of Tobacco Road, but he pulls back from that position in describing how “the picture ended” rather than how his screenplay did. He goes on to declare that “no such ending … was ever shot or even considered”, which seems pretty damn final, but may not be strictly true, since complete accuracy to Steinbeck’s novel was one of Zanuck’s stated aims, according to the commentary – and this is unequivocally the ending used in the book. Note that Johnson says nothing about Zanuck’s hand in the ending that was used, which argues that he may not have known much at all about what went on during the production – or may suggest that Ford actually shot the footage that Zanuck edited. Gallagher – who emphatically does not believe in “the Swiss ending” – has actually gone to the trouble to collect various published accounts of who did what and, predictably, the picture is murkier than Johnson makes out.

Eyman (p. 231) says Nunnally Johnson’s script dated 7.13.39 includes [the] last scene in the truck. Tom Stempel, on Johnson’s authority, says Steinbeck had enthusiastically approved this ending, and had also considered ending his book that way, but that Ford and Zanuck had not decided on the ending, and left it out of the actual shooting script. Ford, in his reminiscences, claims Johnson wrote out the lines in front of Zanuck and him. (628, n. 190)[20]

And, as it happens, Johnson surely had a particular interest in scotching any rumours involving what might be interpreted, however ignorantly, as a scandalous action on the part of Doris Bowdon, with whom he was in love and to whom he was married at the time of his writing.[21]

I thought at first that the “Swiss ending” was a product of Mitry’s wishfully or dreamily confusing the novel with the film. But Mitry’s wording stresses Rosasharn’s action, whereas the novel focusses on Ma’s urging Rosasharn to give succour to the dying man. The rest of Mitry’s account of what happens in the film’s narrative is (1) clearly derived from the film, and (2) very accurate (not always the case for critics). That is, in spite of Johnson’s accusation of boozing and Anderson’s “cautionary tale” and my wishful thinking, Mitry is demonstrably a reliable witness.

This does not mean that he might not be mistaken in this instance. Of course no one would have shot a naked breast for a mainstream Hollywood studio release in 1939, much less an older man sucking a naked breast (Johnson was eighteen years older than Bowdon. I can’t believe I just wrote that). The problem for the ending (the problem Ford ran away from?) would have been how to convey the action of the novel in a film without violating one’s personal taste, or that of the Hays Office, or that of serious critics – presuming that the decision to even consider such an ending would not already have condemned the film in the eyes of demagogues and “all decent Americans”. Interestingly, this is also the problem of even considering adapting the novel and the play of Tobacco Road; and that has to be a problem that Ford would have been thinking about already without, I suspect, a great deal of enthusiasm.

It seems to me that most writers have taken for granted that no sane person would have tried to film the novel’s ending in 1939 (as someone like Erich von Stroheim surely would have even in the late twenties). Yet there are some reasons for making the attempt. (1) Rosasharn’s action is the narrative’s ultimate symbol of hope, which sounds like a more positive ending than one that leaves all the main characters still traversing the state; (2) as suggested, the very “Stroheimian” quality of the ending makes it something of a rehearsal for Tobacco Road; (3) (perhaps allied to the previous) as a joke intended to annoy Johnson and/or amuse cast and crew. It may also be possible that Ford shot the ending as in the novel and knew it was no good, leaving Zanuck to rescue the film by editing it out, something Ford credits him with being able to do very well.

Now you are thinking, “What do all these words about something that maybe or probably did not happen have to do with film criticism?” There are two answers for that. The first is that I am writing in the hope that I can make you see things anew. To imagine that such an ending might have been shot, that such a version of the film might once have existed, is to understand many new things about the cinema all over again. The second is allied to the critical project of reportage – and that is to recognise that there were actually more possibilities in Hollywood, albeit ones that never materialised, than people tend to think these days. The Grapes of Wrath is a materialisation of some of those political possibilities, at least partly impelled by Zanuck’s desire to produce a movie that was faithful to the Steinbeck’s novel. It may not be true that no sane person would have tried to film the novel’s ending, after all.

Here is a still from “Zanuck’s ending”:

Okay, okay, I have kind of exaggerated what goes on in my selection of the moment to capture, but that is partly because although one might hardly notice this instant of Pa’s animation, which occurs near the end of a fairly long take of a monologue by Ma about enduring, it does encapsulate what critics of the film’s ending are trying to say has been done to spoil, soften, the more militant message of what Ford is supposed to have filmed. Significantly for those critics, I believe, this brief moment also points the way toward the substance and strategy of the exaggerated comedy in Tobacco Road.

Critics of “Zanuck’s ending” tend to downplay the fact that Jane Darwell is saying what Ma Joad says in Steinbeck’s novel and, if those words are “optimistic” they are so only to the extent that God’s destruction of all that Job holds dear is optimistic. Moreover, these words are uttered in a moving vehicle: any sense that the film has reached a stopping place, that these people have found the home for which they are searching, any hope beyond faith, is wilful misperception. All of the Joads, not just Tom, are set to wander ceaselessly over the earth.

Two paths are suggested in the novel and the film of The Grapes of Wrath: one active and masculine, and one passive and feminine, In the film the active one is often conveyed in stylised, abstracted long shots, while the passive one is in representational two-shots, like the one above (these are the film’s dominant shot modes. I can’t believe I just wrote that either). The passive response is the one that the other Ford films of the period up to the war seem to endorse consistently (and not always for women); the path of action, on the other hand, carries with it an ethical/historical risk that may shadow even Abraham Lincoln.

Ma’s faith in passivity is the result of lessons learned in the course of the film, as activism is for Fonda. It is also the case that Ma only gradually becomes a pivotal figure. She is not such a figure in the beginning, when Tom is anxious to see Pa again and does not mention her at all, and only assumes the central role in the narrative after Tom goes. When Ma accepts Tom’s departure she is doing what Hannah Jessop in Pilgrimage did not – that is, she is breaking the bond between her and Tom by accepting his call to action. Acceptance is the key here, because it is what allows their apparently conflicting attitudes to be reconciled. This is what happens in the novel too, but in a John Ford film, the parallel with the situation of mothers whose boys become soldiers is quite clear, and is underlined by Ma’s words about how the people can persist even through the worst disasters.

It is also the case that Ma’s acceptance includes Tom’s militance, just as Ford’s films seem to be concerned to display a communal web of relations and moral stances, functional and dysfunctional – not because the community is better than its parts or that it elevates or equalises those parts or that existing in communities is better than existing alone – but because communities, always more or less in transition, such as families or settlements or stagecoaches (or military units) are what we have got.

Without them, what is left?

At one point, [her family] had bought Florence [Owens Thompson] a suburban home as well. And she hated it. She went back to the trailer. And for me, that’s really symbolic because she literally wanted to have wheels under her. This is purely conjecture on my part, but it seems to me the wheels under her are symbolic. “If the hard times come again, I can get up. I can move on. I can survive”.[22]

*****

In point of strict fact, Tobacco Road – the only Ford feature between 1939 and 1941 that qualifies as a minor work – was also the shortest Ford feature since 1936’s The Plough And The Stars (67 minutes). It seems to me that in this context there is the hint of a case for recognising that the studio, and perhaps Ford himself, considered Tobacco Road a lesser work. However, the film has not received “lesser” treatment in the Ford At Fox box; the disc has a picture on it and both sound and visuals are up to the excellent standard of the rest of the set’s contents.

Personally, I am intrigued by how closely the 84 minute length of Tobacco Road approximates that of Four Men and a Prayer (85 minutes), which I dealt with partly in terms of Bertrand Tavernier’s idea of Ford’s as a “peasant cinema”. “Peasant cinema” would seem at first blush to apply far more clearly to Tobacco Road. There is a strangely systematic opposition to Four Men and a Prayer in how journeys are treated. In Four Men and a Prayer far-flung locations edited to obliterate space are linked with the urban future-oriented upperclass; but that mode of transport is denied to/for the rural past-oriented remnants of the underclass that populates Tobacco Road, a film in which everything that happens is local and a significant time is spent getting to and from places. The protagonists are still in motion at the end of Four Men and A Prayer, as they are in The Grapes of Wrath, but in Tobacco Road, as in Drums Along the Mohawk, they have returned to their own place. At the same time both films are, more or less, comedies with uneasy shifts in tone. Four Men and a Prayer ought to be more light-hearted; Tobacco Road ought to be more serious.

Almost no one has much good to say about Tobacco Road.[23]

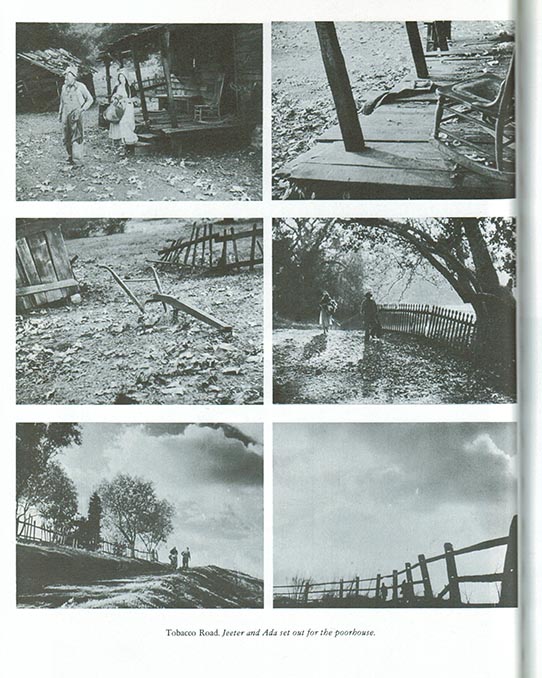

Tobacco Road (1941). Scenarist Nunnally Johnson thought Tobacco Road “a fiasco,” for Ford relied on “old-fashioned bed-slat comedy… crude [and] clumsy.” Albeit there are magic moments: Arthur Miller’s photographic prologue; Bible songs at City Hall and the car dealer’s; walking to the poor farm; and Jeeter’s final speech. But a condescending veneer of euphoric populism has replaced the uncomplicated gaze with which Ford previously viewed simple folk (e.g., Steamboat round the Bend).[24] (214)

This is everything Tag Gallagher seems to want to say about Tobacco Road. Fair enough . . . but “euphoric populism”? “replaced the uncomplicated gaze with which Ford previously viewed simple folk”? “Simple folk”? I thought that Gallagher had previously written, “The ‘simple Fordian characters’ of Shark Island, The Grapes of Wrath and Tobacco Road are Johnnson’s, not Ford’s, and far less complex and ambivalent” (154).

Jean Mitry says that Tobacco Road is not a bad film, an opinion with which most people might disagree, but is actually almost too fair an assessment. Then he spends his time deploring the elements of the novel that have been left out of the film. He does use the term “comic nightmare” to describe the result of Ford’s treatment of the material (56), and this perception is worth all the other words he uses.

By far the most careful piece of critical work on the film occurs in a short video essay by Kevin B. Lee which appears at

http://alsolikelife.com/shooting/2008/02/video-essay-for-905-46-tobacco-road-1941-john-ford/

Even though there are parts of the interpretation with which I do not agree, I do admire the detail and the understanding that it displays.

All this differing opinion, most of it negative, can serve as a spur to our looking again at the film. A certain subtheme of this writing has come to the surface during the time I have been working on the films in this section: questions concerning (some of) the critical opinion around Ford – the sort of criticism his work has inspired and the value of (some of) that criticism. Tobacco Road has given rise to at least three intriguing strands of such criticism, which are discussed in what follows.

*

Jeeter: If Tom was here, he’d he’p us.

Ada: Tom was just about the best of all the children, I reckon.

During the commentary for Grapes of Wrath, Joseph McBride says that Tobacco Road is “a bizarre parody of The Grapes of Wrath”. It seems to me that the parody is quite overt and deliberate, and it adds some dimension to what at first may appear to be an extremely simplistic movie. Tobacco Road is an unsettling movie insofar as its parody can be interpreted as a repudiation of the political stance taken in The Grapes of Wrath. Perhaps calling it a “satyr play” may be closer to the point.

In Grapes Grampa is played by Charlie Grapwin, who plays Jeeter Lester in Tobacco Road. Both are old men who have been defeated, not to say rendered impotent, by the Dust Bowl and its collateral damage. Grampa Joad does not survive the journey, and I think it is made clear that he cannot survive leaving the land that once was his. The parallel is striking and in surely no way accidental.

A similar bit of casting moves pixillated Grandma (Zeffie Tilbury) from one film to the other without a change of name, character or family position. Grandma dies on the road in The Grapes of Wrath; she disappears – a lot – in Tobacco Road and is likely dead somewhere out in the woods by the end of the movie. Grant Mitchell also appears in both films, but in roles that are somewhat different. In Grapes he is “Tom Collins”, the saintly representative of the federal government; in Tobacco he is George Payne, the local bank manager (that is, a representative of private institutional capital), who cannot/will not give Jeeter yet another loan – a pointed contrast and a perverse parallel. Seeing these actors/characters in what is, after all, a setting that bears a striking visual similarity to the setting of the first part of Grapes, imparts a dreamlike quality to the film which goes beyond the routine repetition of various members of “the Ford company” in both movies – like Ward Bond, who plays the friendly California policeman in Grapes, and Lov in Tobacco Road.

Ma Joad and Ada Lester (Elizabeth Patterson) are parallels in quite obvious ways, and Ada is by far the most sympathetic – even the most human – figure in the film. Not only is she the one who seems to suffer the most, she is also the only one who takes delight when others (Pearl, Ellie May) escape the fate which Jeeter has fashioned for them.

Noah (Frank Sully) and Dude (William Tracy) are another fairly clearcut pairing. In The Grapes of Wrath the idiot boy Noah disappears like Grandma does in Tobacco Road (we last see him playing with an improvised toy boat when the men bathe in the river). He is a far more bearable and believable idiot than Dude, who appears to me to be an evil changeling or a pooka (Ada at one point accuses him of not being “a natural son”). Similarly, the slightly loony former preacher, Casy, is mirrored bizarrely by Sister Bessie, also batty and also religious (Marjorie Rambeau). On the other hand, there is no single, direct cognate for Rosasharn in Tobacco Road, although both Pearl, whom we never see, and Ellie May (Gene Tierney) take on aspects of Rosasharn’s position as the young wife who is the mother’s hope for the future.