Southern Italians emigrated to Australia in significant numbers for much of the 20th century. Negative attitudes developed towards them from the start. These were often openly expressed in newspapers and in the Federal and State parliaments. The biggest wave of southern Italian immigration occurred after World War II. By the early 1950s the inner northern and western suburbs of Melbourne (and similar parts of our other cities) were heavily populated by tens of thousands of such migrants from Italy, mainly southern Italy, and from Greece. Smaller numbers came from Germany and Eastern Europe. They came to escape post-war poverty and many found work in then thriving manufacturing industry. Melbourne’s poorer inner suburbs were places where factories made clothing on sophisticated machines and employed thousands to work in them. There were as well heavier industries which made cars and other metal products. New arrivals crowded into rental housing, some living in sheds and lean to’s as well as the house itself. There were lots of small children.

For the descendants of the British stock who lived in those suburbs there was significant cultural shock, fear and distrust. The solution for them was, over time, to move on out to the new suburbs, particularly in Melbourne’s expanding east. But meanwhile adjustments had to be made. New cooking smells, especially that arising from garlic, had to be absorbed. New grocery shops selling ‘exotic’ products like pasta and tomato paste started up. Cafes selling espresso coffee made on hissing machines adorned with names like Faema and Gaggia in big gold letters, sprang up. So did Italian newspapers and, later, Italian cinemas screening unsubtitled films many of them featuring Toto and the comedians Francho Franchi and Ciccio Ingrassia

The Italian others were dubbed ‘dagos’ and ‘spags’. Separation from the mostly Protestant British stock was a constant and was assisted by the deeply entrenched sectarianism of the day. The Catholic Church however descended on the newcomers, brought them into the fold and insisted on their children being educated, mostly by nuns, at some of the poorest schools in Australia. In Brunswick, the suburb north of Carlton, three of those Catholic parish schools (St Margaret Mary’s, St Ambrose’s and St Fidelis’s) were later, when State aid was finally given to private schools, adjudged amongst the most under-resourced in the nation. The wave of Italian immigrants did not, initially at least, flood the public school system with new arrivals. Only handfuls escaped the church’s clutches. Those few were simply placed in classes commensurate with their age and asked to do their best. Teachers too had to cope as best they could.

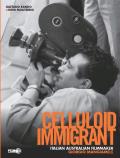

Giorgio Mangiamele, a southern Italian who had moved to the much more sophisticated Rome in the late 40s, was one such immigrant. He came at the age of 26. His move away from the south was an early emblematic sign that he was somewhat different to many of his fellow countrymen and women. He was an atheist, a leftist and had skills as a photographer that eventually enabled him to take the initiative, break away from the rules and confinements set down by his sponsor the Australian Government and establish his own small business in Carlton, the most sophisticated and cosmopolitan of Melbourne’s inner suburbs. His refusal to accept seemingly straight forward government rules of the day was to be something of a mark for his later dealings with Australia’s film funding authorities.

Notwithstanding Carlton’s ‘sophistication’ Mangiamele saw prejudice close up and this was to form the thematic basis of his work in a sphere beyond his photographic business, film-making. From 1953 to 1963 he made six short, medium and feature length films chronicling the experiences of Italian immigrants. For all six he was his own producer and financier as well as the director, photographer and writer or co-writer. These films, with the feature film Clay, made in 1965, form the basis of his reputation as a pioneer working at a time when government assistance to the film industry was non-existent. He was not the only person trying to make films during this time but he did succeed in getting things done, making some movies and having them screened to appreciative audiences. The screenings however were at film societies and in community halls not in commercial cinemas.

Mangiamele sought to emulate the subjects, particularly the struggles of working people, and methods of the Italian neo-realists of the 40s and 50s. He filmed in the streets and cast his family and friends. The influence of Vittorio de Sica is never far away. De Sica was a sentimental film-maker and The Bicycle Thief (Italy 1948) with its artful story of a father and son in distress remains his most loved work. Gaetano Rando & Gino Moliterno’s very comprehensive study of Mangiamele’s life and films traces the influence of De Sica and presents a comprehensive view of the Mangiamele’s life and his career as a film-maker.

After those films made between 1953 and 1963 Mangiamele turned to other subjects and completed two feature films Clay (Australia 1965) and Beyond Reason (Australia 1970). The former was selected for the competition at that year’s Cannes Film Festival. The latter, an attempt at a commercial thriller, was distributed in Melbourne by the American company Columbia Pictures. After that Mangiamele spent the best part of the 70s unsuccessfully trying to get Australian and Victorian Government funding for his projects. He then took a job with the Papua New Guinea Office of Information and worked in that country as a director for three years into the early 80s. When he returned he again embarked on a largely fruitless round of making submissions for funding of proposed film productions.

In the conclusion of their book Rando and Moliterno lead off by asking why he was unable to complete a single film in Australia after Beyond Reason. Was it, they ask, a matter of racial discrimination? Mangiamele apparently believed it to be so. A quote from Scott Murray, another film-maker who has struggled for decades to attract Government funding after his first and only feature which, ironically in this context, was also accepted into one of the official sections at Cannes, proposes: “Australia was too ageist, too narrow in its view about what sort of films ought to be made for there to be space for a sensitive, inventive, deeply-passionate filmmaker like Giorgio Mangiamele.” Mangiamele’s wife Rosemary refers to her husband as “not part of the ‘clique’”.

I can’t help thinking that a part of the problem may have derived from the way that Mangiamele approached the film money lenders. He had never sought to enlist the aid of a producer and continued, it would seem at least, to make his own presentations in what might be designated his own unique manner for assistance. Philip Adams described him as “genuinely heroic and a romantic; in the best Quixotic sense.” These are the words that reflect a stubborn sense of self-belief no matter how inflexible and unsympathetic the always risk averse bureaucrats were and how much they may have wanted him to play by different, more restrictive, rules. Mangiamele probably regularly lamented how smoother, more polished and fully completed scripts by writers and directors who learnt how to play the game were always favoured over the thoughts and ideas of the maverick.

While most of those who have managed to make films about the immigrant experience are noted by the authors, one major figure who is not mentioned similarly chronicled some of these matters. The scriptwriter Jan Sardi was born and raised only blocks from where Mangiamele lived and worked in Carlton. He wrote the scripts for Moving Out (Australia 1983) and Street Hero (Australia 1984) and embedded himself within the industry. His completed and filmed scripts have since gone far beyond that of the immigrant experience, just as Mangiamele wished to do. The only producer mentioned in the book is Mangiamele’s Italian friend, the producer Gino Millozza a producer and production manager who worked with such noted figures as Michelangelo Antonioni, Luigi Comencini, Marco Bellocchio, Francesco Rosi and Lina Wertmuller over several decades. Millozza’s efforts to get Italian financing also came to nothing.

Rando and Moliterno’s book is a most comprehensive look at Mangiamele’s life and work. The details are extremely well-organised and it is written from the perspective of great enthusiasm for the qualities the films contain. Its release is now accompanied by a box set of the director’s extant films made between 1953 (Il Contratto) and 1965 (Clay). The discs are newly remastered by the National Film and Sound Archive and released by Ronin Films. Of particular interest in the box set is a version of The Spag (Australia 1960) designated here as the unreleased version to distinguish it from a separate film made two years later and which used the same title. The latter, some 36 minutes long, is still regarded by many as the director’s most intimate and moving work and the one that resonates most with the influence of Mangiamele’s idol De Sica. What now remains for many is for his only other Australian feature Beyond Reason to be re-presented in public so that the full list of the director’s completed films, at least those made in Australia, can be available.