In the early part of 2009, I was preparing to teach The Jazz Singer (1927) as part of an introductory Media Histories subject for Australian university students. [1] While searching for reading material to pair with the film’s screening, I was challenged to find a recent essay that was not in dialog with Michael Rogin’s treatment of the film in his book Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot, and particularly his claim that blackface helped make Jews white in America. [2]

Given the pervasiveness of citation for Rogin and the expectation that my students would require guidance through the material, I was compelled to undertake a thorough review of his work in preparation for my teaching. In this process I came to identify what appears to be a hostage situation in scholarship: The Jazz Singer is prisoner to Rogin’s thesis that blackface makes Jews white. [3] To find a discussion of the film that avoids this terrain, we have to go back more than fifteen years. [4] The obligation to engage with, or at least give Rogin “a nod,” is so compelling that many authors refer to Rogin as an authority even when they oppose his position. [5] Joel Rosenberg has summarized this phenomenon well when he says that, “the book seems to be designed not so much to be read or used as to be quoted—indeed, it raises the art of the academic sound bite to a baroque perfection.” [6]

The issue is not that The Jazz Singer provides no evidence for Rogin’s argument but rather that he claims evidentiary status for his interpretation of the film’s narrative. Adopt a different reading of the film and, as I will demonstrate, the “evidence” for the blackface/assimilation claim disappears. In this essay I review the logic of Rogin’s argument with a perspective informed by feminist critical thought and close textual analysis that accounts for female agency in the film. Coupling insights from Kaja Silverman’s (1988) discussion of voice and interiority in Hollywood film with Karen Brodkin’s (1998) gender-sensitive analysis of how American Jewish identity was formed in the 20th century, I challenge the masculine bias inherent in Rogin’s argument and aim to dissolve the links that he fabricates between sexual desire, race, and class mobility. [7]

Blackface performance in the US has indeed participated in complex practices of representation, circulating and sustaining stereotypes and caricatures of African-American “types” that are today very offensive. Such performances, however, also made available African-American musical traditions to a wider audience and contributed to their popularization. In arguing that The Jazz Singer is not primarily about blackface and rejecting Rogin’s thesis that blackface made Jews white, this essay is not concerned with the ethics of blackface performance. If blackface is memorable in the film it is due to its placement rather than its prevalence, and to Al Jolson’s star performance. Through a critique of Rogin’s textual analysis, historiography, and rhetoric, this essay reconsiders how the film contributes to discourses of identity and demonstrates the currency that feminist perspectives continue to offer for our scholarship. [8]

White-wash: a surface treatment

In both his 1992 essay in Critical Inquiry and his more well-known 1996 book, Blackface, White Noise, Rogin argues that blackface minstrelsy “turned Europeans into Americans” through the cultural work of films that made “African Americans stand for something besides themselves.” [9] He contends that blackface performance “loosened up white identities by taking over black ones, by underscoring the line between white and black.” [10] According to the argument, Jews used blackface to migrate within the American racial hierarchy from the marked status of Jew to an unmarked whiteness that Rogin characterizes as a process of “assimilation.” Unlike Eric Lott’s argument in Love and Theft (1995), which engages critically with questions of class mobility and conflict, Rogin has little to say about the role of class in the processes of integration, assimilation, or white-washing of Jewish identity in the US. Where Lott sees “love and theft,” Rogin only sees theft. [11] The Jazz Singer, Rogin says, “makes blackface its subject” through a process whereby “white identification with (imaginary) black sexual desire … comes to the surface.” [12] He argues further that, because “blackface promotes interracial marriage … The Jazz Singer facilitates the union not of white and black but of gentile and Jew.” [13] Thus Rogin understands the film to be primarily a story of interracial marriage between gentile and Jew and not, as others have done, a masculine coming-of-age tale set within the context of generational conflict.

Rogin claims The Jazz Singer conveys three stories, “the conversion to sound, the conversion of the Jews, and the conversion by blackface.” [14] But he laments: “Far from separate but equal, so that one story can be rescued from contamination by the others, the film amalgamates all three.” [15] Holding these three stories together is Mary Dale, the shiksa figure. More than the voice, for Rogin it is blackface that makes Jack the Jew attractive to Mary—whom he will eventually wed to produce little blonde, bacon-eatin’ babies, making Jack’s conversion complete by leaving him without a Jewish heir. [16] None of this actually happens in the film; this is the trajectory of Rogin’s interpretation and what he would like us to accept as evidence in an argument that relies on condensations, displacements and substitutions.

Elevating the thread of romantic love and coupling to a position of responsibility for all other possible meaning in the film, he claims that “conversion to sound,” “conversion of Jews,” and “conversion by blackface” are stories, rather than themes. But if we are to understand the film as Mark Garret Cooper (2003) has described it, a classic “ghetto film” of intergenerational conflict that allows Jack to “survive intermarriage without ceasing to be Jewish,” the film cannot provide evidence for an “assimilation” argument, but may still address the related yet distinct issues of integration and a modernization of Judaism in America. [17]

Narrative, Voice, and Female Agency

Exploring the film from a feminist perspective, the coming-of-age tale is the more readily apparent and operates in parallel with the modern transformation of Jewish practice in America. As, in the early half of the twentieth century, practices associated with public and private spheres become more separate and distinct, the family home gains a sacred status and the public arena becomes more secular. Although there is a less visible presence of Jewish practice in public space across the early half of the twentieth century, Reform Judaism is on the rise. Jewish integration in America is facilitated by the coincident modernization of Judaism—allowing one to be Jewish and American.

Asserting that The Jazz Singer is a love story between two people, and not an individual’s coming-of-age tale, Rogin still reads the love story as Jack’s story. He only considers the transformation of the male character in the coupling that he sees as driving the narrative. He ignores Mary Dale’s desire and her agency, and overlooks the transformation of Jack’s mother as well. This dismissal of female agency results in the postulation of a masculinist theory of Jewish experience in America.

Coupling masculinity with blackness, Rogin says that Jack wears the black mask to pursue Mary Dale. It is not the eponymous Jazz Singer’s voice that makes Jack the Jew attractive to Mary the Gentile. Instead, Rogin contends that blackface allows Jack access to what would otherwise be forbidden to the Jew—the Gentile woman. At the base of this argument is masculine desire, associated with female subjugation. And, through some strange substitution, the black mask hides Jack’s Jewish-ness to the degree, it would seem, sufficient to trick Mary Dale.

In a film that spectacularizes sound, Rogin selects a single image, isolates it and elevates it to an iconic status that is meant to bear the weight of the film’s entire narrative and represent the national history of two substantial minority groups in America: Blacks and Jews. “A single image,” Rogin says, “inspired the present study: Al Jolson, born Jakie Rabinowitz in The Jazz Singer and reborn as Jack Robin, singing ‘My Mammy’ in blackface to his immigrant Jewish mother.” [18] This performance, the final coda of the film, he argues, condenses “black labor in the realm of production, interracial nurture and sex (the latter as both a private practice and a unifying public prohibition) in the realm of reproduction, and blackface minstrelsy in the realm of culture.” [19] The image is indeed a condensation, but ambiguous in its meaning because it is open to many interpretations.

Perhaps Rogin’s oversight of female desire is understandable, if not excusable, given that film studies has been over-attentive to looking and not well attuned to listening. I am not suggesting that The Jazz Singer is a “woman’s film” or a woman’s story, but dismissing Mary’s desire and attraction to Jack Robin’s voice, in favor of the story of the blackface mask, makes the love story one of male pursuit that denies female agency.

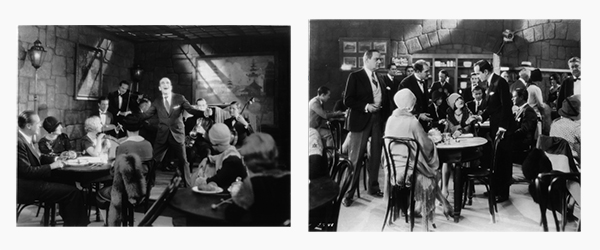

More importantly, an emphasis on appearance ignores the responsibility that sound has for driving the narrative in this particular film. It is, in fact, not a look that triggers Mary Dale’s attention but a sound (as we might expect in this film that is equally about sound itself as a spectacular phenomenon). Descending into the basement club with friends, a wide shot shows Mary Dale entering Coffee Dan’s. Hearing the performer, she pauses and stops her friends on the stairway to see who is singing. Cutting to a close-up of Mary, she looks intently toward the stage as she sees Jack, for the first time, performing “Dirty Hands, Dirty Face.” Importantly, Jack appears sans blackface. Cheating a shot-reverse-shot between Jack’s address to the larger audience and Mary’s focused gaze upon him, a second well-illuminated close-up of Mary emphasizes her interest in him. As Jack launches into his next number, the up-beat “Toot, Toot, Tootsie,” Mary and her companions descend the staircase and cross the floor to take seats at a table in line with center stage. From here they can hear and see Jack as he embellishes the number with a dance step that combines hip-gyrating soft shoe and shoulder isolations that typify the dance style associated with Jewish klezmer music. When Jack has finished his number and returned to his seat, Mary has the maitre d’ summon the performer to her table. Rogin’s masculine reading of the love story overlooks how this encounter is initiated. It is the voice, not the look, which first grabs Mary’s attention and, contrary to Rogin’s suggestion that Jack pursues Mary, it is her invitation that facilitates their introduction.

[W]ith each new testimonial to the authenticity of recorded sound, cinema seems once again capable of restoring all phenomenal losses … However, it is not so much sound in general as the voice in particular which would seem to command faith in cinema’s veracity. The notion that cinema is able to deliver ‘real’ sounds is an extension of that powerful Western episteme, extending from Plato to Helen Cixous, which identifies the voice with proximity and the here and now—of a metaphysical tradition which defines speech as the very essence of presence. [20]

In The Acoustic Mirror Silverman has argued that, “Hollywood’s soundtrack is engendered through a complex system of displacements which locate the male voice at the point of apparent textual origin, while establishing the diegetic containment of the female voice.”[21] Silverman’s project is to explain how sexual difference is structurally reinforced by certain cinematic practices. Although she deals with a period in filmmaking when synch sound conventions were firmly established, long after The Jazz Singer, her remarks are instructive in that they help us to recognize that, in The Jazz Singer, there are only male voices: Jakie/Jack, his father the Rabbi, and Cantor Rosenblatt are featured. Women’s voices are not heard: they are contained in textual inter-titles. And yet, throughout the film, the act of listening is visually reinforced as we see people listening to Jakie Rabinowitz and later, the adult Jack Robin. Given the absence of female voice in a film so much about marking presence through vocal sound, it is the coming-of-age tale about intergenerational conflict between men that is heard most clearly. The love story is effectively muted. Indeed our belief in voice as the essence of an individual, his or her interior self made present through speech, is made clear in The Jazz Singer as Mary Dale and the mother remain silent. We do not come to know these women through the sound of their voices. When adult Jack returns home with gifts and sings in the family parlor to his mother, he also speaks with her. Although Mother replies, it is not clearly audible because she is not picked up well by the microphone.

Female silence in The Jazz Singer is a narrative device that focuses audience attention on the star, Jolson, and on Jack’s coming-of-age tale.[22] Rather than a means of upward mobility for Jack Robin, Mary Dale is a character from what the Warner Bros. might have hoped would be the silent past. She is incidental to the coming-of-age tale about the transformation of Jakie Rabinowitz, and, by analogy, to cinema and American Judaism.

Jews and Race in America

In unpacking the American Jewish success story and its associated origin myths, Karen Brodkin (1998) has criticized what she identifies as a masculine bias in explanations of American Jewish upward mobility. She says that while male intellectuals in the postwar period outlined a masculine Jewish culture, female intellectuals focused on the female experience more generally; and the distinctive experience of Jewish women was neglected.

Brodkin explains how Jewish upward mobility in American society was materially facilitated by federal programs like the GI Bill, and FHA [Federal Housing Administration] and VA [Veteran Affairs] loans, which “functioned as a set of racial privileges” not available to Black Americans.[23] The “not-quite-white” working class Jewish migrants and their offspring of the postwar period had more opportunity to move within the American race and class system than did Blacks. She argues that racial hierarchy relies on gender distinctions which are, in turn, related to class and labor.

[T]he belief that different races have different kinds of gender is the flesh on the American idea of race. If race marked the working class as nonwhite, it did so through a civic discourse that represented nonwhite women and men as lacking the manly and feminine temperaments that were requisites for full membership in the body politic and social.[24]

Rather than constructing the modern American Jew in relation to other Americans in the melting pot, Brodkin argues that the secular American Jew is a modern identity with roots in turn of the century Jewish culture:

When Jews in the 1950s experienced the ambivalence of whiteness as a specifically ethnoracial ambivalence—how to be Jewish and white; or how Jewish to be—they were experiencing whiteness not in relation to a fictionalized blackness but in relation to that real culture of Yiddishkeit.[25] [26]

What has come to be recognized as American Jewish culture is a hegemonic expression derived mainly from eastern European, pre-modern migrant culture. The earlier experience of modernism in Western Europe allowed Jews in Britain, Germany and France to be accepted as citizens with full civil rights whereas the Eastern European Jews had not experienced that privilege in Eurasia and thus the identity they brought with them to the US was still rife with old ways.[27]

Applying Brodkin’s observation about labor and gender to the work of voice in The Jazz Singer, we note that only the voices of male, Jewish, high status individuals are heard. The Cantor holds a prestigious position in the Jewish community. While Jack is not a Cantor, he was groomed for the job; his success on Broadway endows him with the commercial prestige valued in secular American society. He retains, however, his right of return (as it were) to take his father’s place in the synagogue. Jack is able to live in both worlds—the old and new, the sacred and secular, the Jewish and American, because he is a modern American Jew. Indeed, among the privileges that Jack enjoys is one that allows him to play blackface. Rather than a vehicle to becoming white, the blackface performance may equally signal Jack’s already privileged status.[28]

Coming of Age & Life Cycles

Rather than assimilation, it can be argued that The Jazz Singer is a story of integration and modernization: a coming-of-age tale for a man, America, and the movies. The narrative is structured around key moments in the life cycle and religious calendar, which are acoustically marked in Judaic observance with music. Key events occur on yom kippur, the holiest of Jewish observances, at both the beginning and end of the film. The first event sets the film’s story in motion when the 13 year-old Jakie runs away from home. Years later, after having achieved success and Anglicizing his name, he returns briefly, on his father’s 60th birthday, but again is expelled. In the final critical scene Jack Robin returns home—again on yom kippur—to take his dying father’s place in the evening’s services and sing kol nidre. Sung in Aramaic, kol nidre marks the commencement of atonement, the holy day of yom kippur. Rather than a prayer itself, it is a call to congregate for prayer.

Two points are significant here. First, the ideas embodied in kol nidre—to acknowledge that individuals cannot always keep their promises because the needs of others (community) may intervene to cause a change of plans. Second, the fast of yom kippur—an act of penance that marks an individual’s apology for whatever ill may have been done to fellows in the past year. What is sometimes referred to as the “oath” of kol nidre is forward looking and the fast of yom kippur is retrospective. But both are about forgiveness. Combined, they signal the end of one year and beginning of another, so there is a sense of a cycle without end. For most people today, although the literal translation of kol nidre is unfamiliar, the chant is recognized for its musicality and as a marker of the holiest of Jewish holy days.[29]

Kol nidre is the first mention of song in the film, when Papa’s inter-title reads: “Tonight Jakie is to sing Kol Nidre. He should be here!” And Mama’s inter-titled reply is, “Maybe our boy doesn’t want to be a Cantor, Papa.”[30] Cross cutting reveals Jakie singing ragtime in a saloon. Having just reached 13, the age of majority in the Jewish community, at which time he is expected to take moral responsibility for his own actions, Jakie runs away from home after a strapping from his father. As Jakie departs, we hear his father sing kol nidre. Again, at the film’s end, as the father dies, the final departure, Jack sings kol nidre. Whether one envisions symmetry or circularity in this pattern, a more perfect plotting is difficult to imagine. This pattern is further reinforced by the sequencing and pairing of musical performances in the film.

Sacred & Secular—Separate

As Linda Williams (2001) has demonstrated, the film’s conflict between sacred and secular is played out through the pairing of songs whereby a slow and traditional song is coupled with an up tempo jazz tune.[31] To elaborate this observation further, the locations in which the songs are performed map the secular to public space and the sacred to private space. The secular songs are performed in the saloon, coffee house and on stage, while the sacred songs are performed in the synagogue and at home (see Figure 1). The symmetry of opening and closing with jazz tunes abutted by kol nidre has been noted by others but, I will add, inside these bookends is a palindromic structure with the sacred as secular in the narrative center of the film, marking the critical point when Jack begins his return journey to New York.[32]

Figure 1

Secular & Sacred songs map onto correspondingly Public & Private spaces

Secular (My Gal Sal) Saloon

Secular (Waiting for the Robert E. Lee) Saloon

Sacred (kol nidre by Papa) Synagogue

Secular (Dirty Hands, Dirty Face) Coffee Dan’s

Secular (Toot, Toot, Tootsie) Coffee Dan’s

Sacred as Secular – Rosenblatt sings Yartzeit on stage “at popular prices”

Secular (Blue Skies to Mama) Home

Secular (Mother of Mine at dress rehearsal to Mama) Theatre

Sacred (kol nidre by Jack) Synagogue

Secular (My Mammy) Theatre

The pattern of mapping secular song to public space and sacred song to private space is inverted by the two performances at the film’s mid-point. The first of these two is by the non-fictional and famous Cantor Rosenblatt (see Figure 1). His presence on stage “at popular prices” entices Jack into the theatre. Rosenblatt’s performance of Yartzeit, a song to commemorate the deceased, causes Jack to reflect on his father, whom we see in a match-cut flash back that suggests a parallel between Rosenblatt’s stage and the synagogue of Cantor Rabinowitz. The Hebrew word habima is used for both a theatrical stage and the raised platform upon which the Cantor and Rabbi stand before the congregation in a synagogue.

Following Cantor Rosenblatt’s stage solo, Jack returns home and attempts to sing ‘Blue Skies’ (a secular tune) to his Mama in the family parlor. His father enters the room, shouts his objection and Jack is once again dismissed from the family home. Jack’s expulsion renders ‘Blue Skies’ an incomplete number and reinforces the pattern that has been established: the secular belongs outside, in the public arena, so that the home can remain a sacred space.

Williams opens the first chapter of Playing the Race Card (2001) with an epigraph from Christine Gledhill that asserts melodrama’s central role in modernization through its participation in the organization of “a newly emerging secular and atomizing society.”[33] Key to modernity’s reorganization of social order is a reconceptualization of public and private. Williams explains that, “Melodrama is fueled by nostalgia for a lost home.”[34] For The Jazz Singer, I propose that it is not a lost home, but rather a different kind of place that is longed for. The secular and modern Judaism that is emerging in America needs to establish its place in a multicultural society. This is achieved, in part, by maintaining Jewish observance in the private space of the family home and synagogue, while on the public streets embodied performance and display become less common. Cantor Rosenblatt’s appearance on stage suggests another safe place for the public performance of Judaism, albeit simultaneously implying the commoditization of tradition. The commercialization of religious and cultural rites becomes a hallmark of secularized American society in the latter half of the 20th century. Such dislocation and commercialization of African-American musical tradition is woven into Rogin’s criticism of the film but he stops short of applying the same analysis to the Jewish tradition that Rosenblatt’s performance signals. I suggest that Rosenblatt’s performance is made more significant by the fact that it occurs midway through the story as Jack begins his return journey homeward. He has left New York, been across the nation, met Mary Dale in San Francisco, and is on his way back to Broadway.

Integration not Assimilation

The duality of old world and new country is ever-present in The Jazz Singer, and the coming-of-age tale embedded within the annual cycle of yom kippur reinforces a theme of community. When Jack’s big day arrives, he does not keep his promise to his troupe (his new family); they end up postponing the opening night show so that Jack can take his father’s place in the synagogue as the father lies dying next door. Jack’s career, it turns out, is not the most important thing in his life. He has renegotiated his career and his commitment to the troupe in order to do something for the community and family that raised him. Since Jack ends up back on Broadway at the end of the story, it seems the film’s emphasis is toward accommodation and integration rather than assimilation as disappearance. Rogin, however, sees it differently.

The movie was promising that the son could have it all, Jewish past and American future, Jewish mother and gentile wife. That was not what happened in Hollywood. The moguls left their Jewish wives for gentile women in the 1930s and eliminated Jewish life from the screen. They bid farewell to their Jewish pasts with The Jazz Singer. Americanized Jews ultimately would retain Jewish identities, but there was no going back to the lower East Side.[35]

Indeed this did happen in Hollywood but it happened well after the film debuted and not to all of Hollywood’s Jewish executives. To read the film against what happened later is a mistake of historiography, yet similarly unsustainable claims about the Jewishness of Hollywood have had equally uncritical reception and circulation.

Neal Gabler’s An Empire of Their Own (1988) epitomizes the contradictions of this stance. In the book’s earliest pages Gabler says that, “Hollywood Jews … were a remarkably homogenous group with remarkably similar childhood experiences”, and he then proceeds to detail their very different upbringings.[36] Adolph Zukor was from a Hungarian village, orphaned at age seven and raised by his uncle, who was a religious scholar, Zukor was poor but erudite. Carl Laemmle was born in Laupheim, SW Germany, home to the largest Jewish population in the region. “His boyhood home,” Gabler writes, “was a large, airy cottage surrounded by loganberry bushes and with a fishing pond nearby, and his youth seems to have been routine.”[37] Having been apprenticed to a stationer suggests a middle class upbringing for Laemmle, although Gabler calls him “uneducated” at times.[38]

At the age of three, Louis B. Mayer’s family immigrated to Canada from Minsk, a city whose population was half Jewish. In Minsk the family were urban poor, the father a peddler. And, the Warner Bros are alternately treated by Gabler as individuals and as a collective. Their parents (and Harry Warner) were from Krasnosielc, a village in the (Russian) Pale of Settlement where Jews were made to live from 1791. With the rise of pograms from 1881, Jews began to flee. The Warners were among those who left in 1883. The father, Benjamin Warner, was present and devout (in contradistinction to Zukor and Laemmle’s fathers). Gabler also explains how each of the moguls’ fathers coped distinctly with life in America: one became a drunken womanizer, another a more devout Jew. These background stories do not suggest uniformity and hardly constitute the “homogenous group” Gabler tries to create in his glossing of Jewish similarity.[39]

Echoing Gabler, Rogin says that Jakie Rabinowitz “adopts a black mask and kills his father.”[40] Thus, “the cultural guilt of the first talking picture arises from assimilation and parricide.”[41] Assimilation, for Rogin, is abandonment of Judaism. To become American is to reject Judaism. “Jewish past and American future, Jewish mother and gentile wife”—Judaism has no future and it does not belong in America, according to Rogin’s logic. Defining assimilation as disappearance is not without its precedents. The phrase “assimilated Jew” has been used to describe German Jews who so thoroughly denied their heritage that they were deemed complicit in the Holocaust. “Assimilated Jew” can carry the connotation of “traitor” but that is not really the argument that Rogin is making. He is saying that there is no place for Judaism in America and to get away from his own identity, Jack Robin assumes the identity of an Other through blackface.

To the contrary, Jack Robin comes to represent the dominant practice of Judaism in modern American society and indeed a secularization of Jewish practices and identity.[42] Religious observance becomes a private affair, confined to the home and house of worship, and not necessarily visible on the body or in the street. Rather than the abolition of Judaism, there is a transformation of its practices.[43]

The film demonstrates an important distinction between assimilation and integration. Assimilation (as Rogin uses the term) involves the displacement of a subordinated group by a dominating one. Culture and communication theorist Richard Rogers distinguishes that notion of assimilation from integration, which “involves internalization of some or all the imposed culture without (complete) displacement or erasure of native culture and identity.”[44] It is never clear in the film that Jack Robin has officially converted (i.e. abandoned Judaism). In what is effectively the last plot point, Jack returns to sing in his father’s place at synagogue, performing the service that he would have done those many years earlier if he had not run away. Following this is the closing scene, a coda effectively, in which he sings “My Mammy” on the Broadway stage to his mother seated within the audience. It is the mother who has converted, not from Judaism, but from old world ways to modern ways in the footsteps of her son.

It is difficult to follow a clean line through Rogin’s thesis. Blackface masquerade, he says, “reinforced rather than challenged racial and gender hierarchies”, and yet he also says that blackface “frees the jazz singer from his ancestral, Old World identity to make music for the American stage.”[45] How can it be both ways? If Jews are not quite white, and blackface has the dual power to reinforce racial hierarchy and facilitate racial transformation, what was then reinforced is Black difference not differences at a time when, important for this story, Jews were white-ish.

Culture & Authenticity

Can national identity accommodate difference? The essentialism upon which the blackface/assimilation argument is based reveals its inadequacy from the very start. If wearing blackface allows Jews to become White, then claims of authenticity for Black culture and Black jazz are undermined. If one can perform one’s way into White through temporary masquerade as Black, then neither category is fixed and any claims to racial authenticity are called into question. Rogin’s objectification of Jews fixes them into a space of religion that comes from elsewhere and else-when—the Jewish past. Jack Robin is not allowed to be a Jew and American. This position seems even more odd when one takes a moment to consider how frequently we still read or hear reference to “Jewish Hollywood.” If it is impossible to be Jewish and American, why do people persist in characterizing Hollywood as Jewish?

For African Americans, the argument, quite typically, shifts all questions of class to race. Religion and race are thus both fixed as essential features of ontology so that they can provide the “authentic” status that Rogin’s argument requires.[46] To sustain a masculinist vision of assimilation, not only Black subjectivity but also female desire is dismissed. Such simplification is fundamentally at odds with an understanding of culture as process and forecloses the option to recognize cultural change or hybridity. Assuming such a static view of culture also poses a particularly ironic challenge in this case because change and hybridity are notable features of jazz, which surface in its frequent “indeterminancy.”[47]

The concept of “transculturation” explains culture as a “relational phenomenon that itself is constituted by acts of appropriation.”[48] Conceived this way, Rogers explains that culture is “not an entity or essence that merely participates in appropriation” and appropriation is not simply theft.[49] How any practice can be made one’s own depends not simply upon the taking but emerges through processes of transformation. Attending to the process of appropriation rather than the “intent, ethics, function, or outcome,” results in a less evaluative notion of appropriation.[50] The concepts of “cultural exchange, domination, and exploitation,” Rogers argues, “presume the existence of distinct cultures. [U]nless culture is mapped directly onto nation, territory, or some analog thereof—a highly problematic move—the boundaries here are, at best, multiple, shifting, and overlapping.”[51]

The notion of shifting, multiple, and overlapping boundaries articulates the movement of feeling that we can identify in Jolson’s voice across the divide of sacred Jewish and secular African-American. Williams has observed that the “blackface ‘Mammy songs’ have a veneer of folk authenticity, and a marked lack of syncopation, that allies them with the Kol Nidre,” while the jazz tunes represent the modern America.[52] Rather than the visual register of a blackface mask, it is the vocal similarity, the musical familiarity that joins African-American and Jewish expression in Jolson’s performance. The fact that we see the mask being applied, but cannot see the work of the voice, suggests that the duality is internalized. The “jazz singer” is himself a hybrid and his existence challenges our understanding of discrete cultures and a static or unified subject. Jewish assimilation is, for Rogin, equivalent to disappearance. His argument requires fixed categories of White and Black, masculine and feminine, which disallow transformation and cannot accommodate hybridity.

What does The Jazz Singer have to say?

It is an oversimplification to say that The Jazz Singer is about blackface or that blackface is the film’s most important motif. The film tells a complex story of modernization in America as it weaves together threads of nation, migration, generation, and representation to express them in ways that are made especially resonant through voice and song. I have offered three types of criticism here. I have argued that to claim narrative primacy for the theme of romantic coupling in The Jazz Singer, one must necessarily acknowledge and account for female agency because the film does not provide evidence to sustain a love story based in masculine pursuit alone. Secondly, I have demonstrated how the film is engaged with discourses of integration as distinct from a notion of assimilation. The discourse of integration is, moreover, embedded in the US nation-building project in the modern era of the twentieth century. Finally, I have demonstrated that the hybridity of jazz serves as a metaphor for the hybrid American identities that begin to emerge with the twentieth century and which become dominant by century’s end. Less explicitly articulated in the film but nevertheless present is the possibility of Reform Judaism as a symptom of modernity, embodied in Jack Robin.

By offering an interpretation of the film which acknowledges Mary Dale’s agency, I have shown that this love story is not one of male pursuit and, moreover, that the love story is secondary to Jack’s coming-of-age tale. Rather than a story of assimilation as cultural abandonment and disappearance into the melting pot, The Jazz Singer articulates one version of how integration operates in a multicultural society. This is not to say that assimilation has not also been a part of the American immigrant experience. Nevertheless, in The Jazz Singer the emphasis is on hybridity—a characteristic that marks jazz and twentieth century American experience and identities.

[1] Research for this essay included consulting the “Three-Disc Deluxe Edition” Warner Home Video DVD (2007) of the 1927 film The Jazz Singer (dir. Alan Crosland).

[2] Michael Rogin’s Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot (Berkeley: UC Press, 1996) is the more famous of the two works considered here. The earlier essay, “Blackface, White Noise: The Jewish Jazz Singer Finds his Voice,” Critical Inquiry 18, No 3 (Spring, 1992): 417-453, developed the thesis that frames the later book.

[3] I say “Rogin’s thesis” but as early as 1991 Sander L. Gilman posed the question, “Does black-face make everyone who puts it on white?” (p. 238) Rogin is either unaware of Gilman’s critical work, The Jew’s Body (NY: Routledge), or he fails to acknowledge the precedent that Gilman provides.

[4] Even Mark Garrett Cooper (2003) whose understanding of the film contradicts Rogin’s, still cites him with authority to my confusion. Cooper’s description of the film as a story of intergenerational conflict and mixed identity appears on pp.160-63, followed by reference to Rogin’s argument about blackface and Jewish “race” on page 174. See Cooper’s Love Rules: Silent Hollywood and the Rise of the Managerial Class (Minneapolis, U. of Minnesota Press). Linda Williams (2001) provides, in my opinion, the best critique of Rogin, and does so with a gentle manner, in Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson (Princeton, Princeton UP). Articles predating Rogin’s publications include Charles Wolfe’s “Vitaphone Shorts and The Jazz Singer, Wide Angle Vol 12, no 3 (July 1990): 58-78; and Jonathan Tankel’s “The Impact of The Jazz Singer on the Conversion to Sound,” Journal of the University Film Association Vol 30, no 1 (1978).

[5] See, for instance, Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1998) and Nicholas M. Evans, Writing Jazz: Race, Nationalism, and Modern Culture in the 1920s (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc, 2000).

[6] Joel Rosenberg, “Rogin’s Noise: the alleged historical crimes of The Jazz Singer.” Prooftexts: A Journal of Jewish Literary History (Winter-Spring, 2002): 224.

[7] See Karen Brodkin How Jews became White Folks and What that says about Race in America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 1998) and Kaja Silverman The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988).

[8] This essay has benefited from feedback I received at SCMS 2010, Film & History Conference 2010, Western Jewish Studies Assn. Conference 2011 and discussion with several colleagues. I am particularly grateful to Richard Maltby, William Whittington, Victoria Haskins, and Lawrence Baron.

[9] Rogin 1996, 12; Rogin 1992, 417.

[10] Rogin 1996, 34.

[11] Eric Lott Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York: Oxford UP, 1995). See also Lott’s “’The Seeming Counterfeit’: Racial Politics and Early Blackface Minstrelsy,” American Quarterly, Vol 43, No. 2 (June 1991): 223-254.

[12] Rogin 1996, 79.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Rogin 1996, 80.

[15] Ibid.

[16] According to Jewish tradition, to be known as a Jew within the Jewish community, one must have a Jewish mother. Without undergoing proper conversion, the gentile woman’s issue from a Jewish man are gentiles.

[17] Mark Garrett Cooper Love Rules: Silent Hollywood and the Rise of the Managerial Class (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2003): 160-63. Jonathan Tankel places the film in the tradition of “the ethnic story.” Jonathan Tankel, “The Impact of The Jazz Singer on the Conversion to Sound,” Journal of the University Film Association (U. of Illinois) 30, no.1 (Winter 1978): 21-25.

[18] Rogin 1996, 4-5.

[19] Rogin 1996, 5.

[20] Silverman, 43.

[21] Silverman, 45.

[22] I am grateful to Bill Whittington for sharing with me his perceptive and critical insights on film sound and The Jazz Singer in personal communication.

[23] Brodkin, 50.

[24] Brodkin, 101.

<[25] Brodkin, 185.

[26] Yiddishkeit literally means “Jewish essence” but latterly came to mean the legacy of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish cultural traditions and practices more broadly.

[27] Brodkin, 105.

[28] I acknowledge the insightful comments offered by the anonymous peer reviewers on this point.

[29] I am grateful to Rabbi Shoshanna Kaminsky for her insight and confirmation on this issue.

[30] A Cantor sings the prayers and leads the congregation and/or choir in a synagogue but is not normally the congregation’s Rabbi.

[31] Linda Williams Playing the Race Card (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001): 138-143.

[32] See Tankel (1978) and Joel Rosenberg’s “What you ain’t heard yet: the language of The Jazz Singer.” Prooftexts: A Journal of Jewish Literary History. (Winter-Spring, 2002): 11-54.

[33] Christine Gledhill quoted in Williams, 10.

[34] Williams, 58.

[35] Rogin 1992, 426.

[36] Neal Gabler An Empire of their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (NY: Crown Publishers, 1998): 3.

[37] Gabler, 48.

[38] Gabler, 57.

[39] Similar glossing of difference and individuality under the assumed sameness of Jewish-ness is asserted by Lary May, Screening Out the Past (Oxford, 1980) particularly Chapter Seven, “The New Frontier: ‘Hollywood,’ 914-1920,” and Steven Alan Carr in Hollywood and Anti-Semitism: A Cultural History Up to World War II (Cambridge, 2001).

[40] Rogin 1992, 419; 1996, 79.

[41] Rogin, 1992, 422.

[42] One might be tempted to consider the philosophy of cosmopolitanism here, as it was articulated by Kant to retain a role for nation states. Since cosmopolitanism more recently has come to mean a global ethic that overcomes nation states, it is perhaps more confusing than explanatory. I am arguing that the secularization of Judaism in the US is an aspect of modernity as it is articulated in the US across the 20th century.

[43] Karen Brodkin elaborates this in How Jews became White Folks and What that says about Race in America.

[44] Richard A. Rogers, “From Cultural Exchange to Transculturation: A Review and Reconceptualization of Cultural Appropriation.” Communication Theory Vol. 16 (2006): 481.

[45] Rogin 1996, 40; 58.

[46] In the case of Jews, however, it is important to note that discourse often maps race onto religion in a way that makes race and religion appear fused.

[47] Nicholas M. Evans Writing Jazz: Race, Nationalism, and Modern Culture in the 1920s (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc, 2000): 99.

[48] Rogers, 475.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Rogers, 476.

[51] Rogers, 491.

[52] Williams, 157.