Introduction

The story of Alexander Pearce’s arduous journey through southwest Tasmania and the gruesome fate that befell his comrades on their famishing trek across the island state has been narrated many times in song, on the stage, in print, and on screen. Most famously, the story of Pearce’s escape with seven other convicts from the Sarah Island penitentiary in Macquarie Harbour in 1822 was told with dramatic license in novelist Marcus Clarke’s His Natural Life.[1] The historic convict narrative, itself grounded in actual events, was later renamed For the Term of His Natural Life and made into a film shot at Port Arthur in 1908 by Charles McMahon; remade in 1911 by Alfred Rolfe as The Life of Rufus Dawes; remade again in 1927 by Norman Dawn; then adapted once more as a TV miniseries in 1983 by Rob Stewart. Craig Godfrey later directed a straight-to-video, schlock horror-comedy called Back from the Dead (1996) at Port Arthur and Hobart, featuring the modern-day resurrection of a cannibalistic killer convict called Kavendish who was imprisoned in Port Arthur and who “is loosely based on Alexander Pearce.”[2] Tracing Pearce’s Gaelic heritage, Barrie Dowdall filmed a documentary for Ireland’s Channel 4 titled Exile in Hell (2007). More recently the horror film Dying Breed (Jody Dwyer, 2008) imagines Pearce’s inbred descendents feasting on unwary travellers who venture into the wilderness in search of the Tasmanian Tiger. That same year Michael James Rowland directed a carefully researched, hour-long ABC docudrama called The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce. Finally, Tasmania writer-director Jonathan Auf der Heide teamed up with Melbourne cinematographer Ellery Ryan to film the beautifully crafted feature Van Diemen’s Land in 2009.

Each of these films rightly treats the location of Pearce’s story as central to the action, yet each presents a different view of Tasmania. According to geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, “Place is a center of meaning constructed by experience.”[3] In what ways, I ask, is the “experience of place” theorised by Tuan mediated within Tasmanian films to produce a sense of the beautiful but sometimes harsh, threatening island landscape as increasingly familiar, yet persistently strange? Further, since many films diegetically located in Tasmania take considerable liberties with the geographic locations they purport to represent, what qualitative difference does it make where the story is set and filmed?

To address these questions, this longitudinal case study brings together historical, aesthetic, and spatial perspectives on film to develop a geocritical analysis of Tasmanian cinema. Bertrand Westphal, one founder of the geocritical approach to textual analysis, describes it as an exploration of the interplay between diegetic spaces and actual places.[4] The intellectual heritage of geocriticism is located in the “spatial turn” associated with the work of Edward Soja[5] and Fredric Jameson[6] in literary and cultural studies, and that of geographical researchers such as Derek Gregory[7] and Tuan.[8]

Tuan suggests: “ ‘Space’ is more abstract than ‘place’. What begins as undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value.”[9] While place and space are contested terms and some theorists, such as Michel de Certeau, reverse Tuan’s distinction, this article works with a phenomenological conception of place as the experience of space. Like Tuan, phenomenologist Christopher Tilley contends that places “may be said to acquire a history, sedimented layers of meaning by virtue of the actions and events that take place in them.”[10] One way this occurs is in the production of “spatial stories,” which Certeau defines as cultural narratives that “traverse and organize places: they select and link them together; they make sentences and itineraries out of them.”[11] Pearce’s journey is an infamous example of such a spatial story. Representations of landscape in cinema, by extension, do far more than frame the environment as a background against which narrative action plays out; films offer landscapes for aesthetic contemplation in ways that generate symbolism and produce cultural meaning, as a growing number of researchers attest.[12] Building on this body of work, I aim to demonstrate how cinematic narratives contribute to the accrual of cultural meanings on geographic locales, both in the places represented on screen and in what the films displace when, with cinematic sleight of hand, one shooting location doubles for another. I argue the Tasmanian wilderness through which Pearce travelled cannot be reduced to a symbolic space and geocriticism offers a research framework for interpreting cinematic landscapes that does not rely exclusively on the somewhat reductive analysis of Gothic spatial symbolism that prevails in critical and creative accounts of the Tasmanian landscape.

Pearce’s Journey

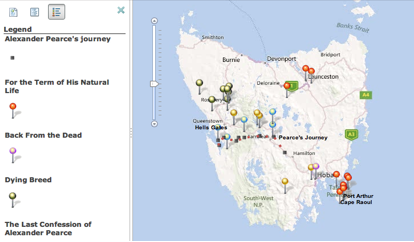

Figure 1: A map of Pearce’s journey and the shooting locations for the films that tell his story.

After escaping with fellow convicts Robert Greenhill, Matthew Travers, Thomas Bodenham, Alexander Dalton, John Mather, Edward Brown, and William Kennerly, it took Pearce forty-nine days to travel from Macquarie Harbour to the sparsely settled agricultural area of central Tasmania near Ouse. September, the month of the escape, averages twenty days of bitingly cold rain with occasional hail and snow. In these miserable conditions, Pearce traversed over two hundred kilometres without a compass. Convicts were notoriously ill informed about Australian geography, as is evident in the attempt by twenty absconders to walk from Sydney to China in 1791, believing: “China might be easily reached, being not more than a hundred miles distant, and separated only by a river.”[13] Similarly, Pearce’s party aspired to steal a boat and sail thousands of kilometres to China or the United Kingdom.[14] Even the navigational expertise of former seaman Greenhill, the convict who led Pearce’s escape party (the first to instigate cannibalism and the last to be eaten), was challenged by Tasmania’s wilderness. The dense canopy of foliage and overcast conditions would have made navigating by the sun extremely difficult and landmarks such as Frenchman’s Cap were frequently obscured by cloud and mist.

A 2009 Australian Geographic article documents the story of six fighting fit members of the Tasmanian State Emergency Search and Rescue Service who became the first and only people to walk in Pearce’s footsteps. The hikers had modern orienteering and camping equipment and, most importantly, ample food. Unlike the convicts, they were able to plot the most viable route through the terrain, yet even then they sometimes covered as little as three kilometres in a twelve-hour period. They described the arduous, muddy, leech infested ordeal as: “akin to doing an all-day gym session carrying a heavy pack while taking a shower.”[15] Members of the expedition reported that “Despite lugging the latest navigation gear, we found it at times impossible to maintain orientation in the silent, thick understorey of bauera, melaleuca, hakea, cutting grass and banksia that combines to form a multi-dimensional spider’s web often concealing rock escarpments.”[16]

As the Search and Rescue team’s testimony suggests, the forbidding landscape and tangled foliage through which Pearce struggled makes a cruel prison. Indeed, only the most “disorderly and irreclaimable convicts” were sent to Sarah Island and once there they undertook backbreaking labour cutting Huon pine to build ships.[17] By the time Dawn shot his film in 1927 the towering stands of pine along the dark waters of the Gordon River near Sarah Island had been depleted and Dawn’s art department trucked huge replica logs to the riverbank at Dundas, near Ryde in New South Wales where a well-fed crew of extras enacted scenes of indentured servitude.[18] In reality, the convicts had inadequate clothing or shelter and were malnourished and constantly ill with scurvy. Their meager rations consisted of rancid “brine-cured pork or beef, two or three years old,”[19] supplemented with some oatmeal and about 500g of bread laced with ergot, a fungus that causes grain to rot, thereby preventing convicts from hoarding rations for a jailbreak. Ergot poisoning causes cramps, seizures, gangrene, and psychotic, hallucinogenic symptoms that may have augmented the effects of hypothermia and starvation, contributing to the bloodshed that occurred after the fugitives fled Macquarie Harbour.[20]

When Pearce was finally recaptured after several months at large his confession was not believed. The authorities thought he was lying to protect felons who were still on the loose and promptly returned him to Sarah Island. He escaped again in November 1823, this time with the hapless convict Thomas Cox. Knowing the difficulties of the easterly route, they headed north toward the Pieman River, incorrectly believed to have been named for Pearce after he cannibalised Cox on its banks. Historians have shown there is no evidence that Pearce was a pie maker by trade, or that he reached as far as the Pieman River before killing Cox and surrendering to the authorities. After giving himself up on the banks of the King River near Strahan, he was hanged in Hobart in 1824, leaving no known descendants other than those imagined in Back from the Dead and Dying Breed.

Cannibalism and Convicthood

Fig 1: Cannibalism rots your teeth. Gabbett in For the Term of His Natural Life (Dawn, 1927)

Early versions of the story represent Pearce as a fearsome figure: the inhuman brute called Matt Gabbett in Clarke’s novel stands in for Pearce. Cannibalism, at least in its cinematic manifestations, evidently enlarges one’s teeth and causes them to decay, yet Pearce looked very little like the gigantic beast in whose “slavering mouth, his slowly grinding jaws, his restless fingers, and his bloodshot, wandering eyes, there lurked a hint of some terror more awful than the terror of starvation—a memory of a tragedy played out in the gloomy depths of that forest which had vomited him forth again.”[21] Transportation records and a portrait drawn when he died indicate Pearce was nondescript and slight of build, just 160cm tall.

Fig 2: Cannibalism rots your teeth. Pearce in Dying Breed (Dwyer, 2008)

Law historian Katherine Biber presents evidence that “The discourse of cannibalism is a repeated and powerful trope in colonial contact and conflict” that has been “wielded discursively to differentiate the colonial citizen from savagery, atavism and abjection, all of the things that are outside law.”[22] Here the term “citizen” distinguishes settlers from convicts and Aborigines, both of whom lacked agency and autonomy and were typically considered adversaries in disputes over land, stock, or provisions. Historically, cannibalism was a last resort during extreme deprivation like that faced by Pearce and his comrades, shipwrecked sailors, or famine-stricken indigenous tribes. The link between transgression and social disadvantage is strong and “cannibalism should come as no great surprise when we consider the chronic food shortages and periods of scarcity that often afflict those who practice such rituals.”[23] Pearce ultimately became “a symbol of anti-authoritarianism and endurance of the bleakest conditions: in twice escaping the hellhole penal settlement of Macquarie Harbour, Pearce not only undermined the British penal code, but his descent into cannibalism represented a persuasive condemnation of the inhumanity of ‘the system’ itself.”[24]

The Gothic Landscape and the Prison Island

Representations of what Gerry Turcotte calls Tasmania’s “uncanny landscape” have most often been theorised in relation to the Gothic, which has from its inception “dealt with fears and themes which are endemic in the colonial experience: isolation, entrapment, fear of pursuit and fear of the unknown.”[25] For the Term of His Natural Life exemplifies colonial Gothic literature in its crumbling architecture, awe-inspiring landscapes, an atmosphere of anxiety, and a story involving isolation and the fragmentation of identity: Nobleman Richard Devine is wrongly sentenced to hard labour in the Australian penal colony where, under the assumed name of Rufus Dawes, his path crosses that of Gabbett. Unlike his historical counterpart, however, Gabbett’s second escape is from Port Arthur rather than Macquarie Harbour.

In cinema studies David Thomas and Gary Gillard[26] attribute the first use of the term “Australian Gothic” to Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka’s discussion of a production cycle in the 1970s including the films of Peter Weir and Jim Sharman.[27] More recently film scholars including Emily Bullock, Jonathan Rayner, and John Scott and Dean Biron have researched the trope.[28] In her extended study of Tasmanian landscape representations in writing, art, and photography, Roslynn Haynes claims “Gothic was first used in relation to Tasmania only in 1976.”[29] By 1988 Jim Davidson had developed the idea of the Tasmanian Gothic as a theme or style extending across novels, plays, and films set in an “uncommonly picturesque” landscape haunted by the past.[30] Following Davidson, Bullock suggests “The past is a persistent presence in films about Tasmania, melding with and reinforcing a sense of isolation, menace and melancholy that is so frequently made to appear natural in its landscapes.”[31]

The films that take up Pearce’s story play on fears of monsters lurking in the dark forests of Gothic European folklore, yet as Scott and Biron observe, Australian Gothic cinema is distinctive because there is often “nothing to fear but space itself.”[32] In Pearce’s case, I contend, it is interaction with the landscape that produces the monster. Further, cinematic evocations of the Tasmanian landscape exceed what can be contained within or explained by the highly symbolic conventions of Gothic spatial representation. Consequently, Gothic readings need to be supplemented by an understanding of cinema that is at once more pragmatic, in that it takes account of the logistics of production, more historical, in that it accounts for changing socio-political perspectives over time, and more phenomenological, insofar as it attends to the audience’s experience of and response to screen aesthetics.

Despite being the part of Australia that most resembles the United Kingdom in climate and topography, Tasmania was also considered the most fearsome penal colony. In 1642 Dutch navigator Abel Tasman named the island for Governor-General Van Diemen, but after decades of convict transportation “when that name had become so tarnished with stories of criminality and cruelty that respectable settlers would no longer endure it” the state was renamed Tasmania in 1855.[33] In For the Term of his Natural Life and its adaptations, Tasmania’s towering trees, icy waters, and steep cliffs literally form a fortress incarcerating convicts in a hell on earth that is all the more punitive and purgatorial for its terrible isolation.

While at Macquarie Harbour, Dawes is held in solitary confinement on Grummet Rock, a small island near the Sarah Island penitentiary, which is offshore the larger prison island of Tasmania, located off the south coast of the greatest of all prison islands, the convict continent of Australia. In “A Phenomenology of Islands” Pete Hay tests the idea that islands are defined by their edges: “Islanders,” he writes, “are more aware of and more confronted by the fact of boundaries.”[34] This sense of confronting the boundary of the island prison is most prominent in representations of Hell’s Gates, the treacherously shallow sea channel that guards the narrow entry to Macquarie Harbour. In convict days the rocks at the harbour mouth were reportedly painted with a line from Dante’s Inferno, a narrative of the descent into Hades: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” As Hayes describes it, the “landscape enacts and reinforces the repression and punishment meted out by society, brutalising oppressors and oppressed alike. Convicts are constrained not in haunted castles or subterranean vaults, but in a natural prison whose walls are the land itself: first the storm-swept coast at Macquarie Harbour with its Hell’s Gates, then the Tasman Peninsula, with its two ‘locks’ upon the door.”[35] The locks Haynes refers to are geographic features preventing escape from the Port Arthur penitentiary: the Southern Ocean and the narrow, heavily guarded sandbar at Eaglehawk Neck. This “Gothic prison” metaphor is pervasive and many scholars such as Turcotte refer to Australia itself as “the dungeon of the world.”[36]

If, as Tuan argues, “Art trains attention and educates sensibility; it prepares one to respond to the character of alien places and situations,”[37] then the narrative cycle examined here cultivates perceptions of the Tasmanian landscape and locates Tasmania in relation to shifting conceptions of national identity. In early Australian cinema, “the relationship between man and landscape first appears as purely an oppositional one” as Australian settlers struggle against drought, isolation, bushfires and floods.[38] This is evident in Clarke’s novel, yet by 1927 attitudes were already shifting as Australia began to reflect on its convict history.

For the Term of his Natural Life

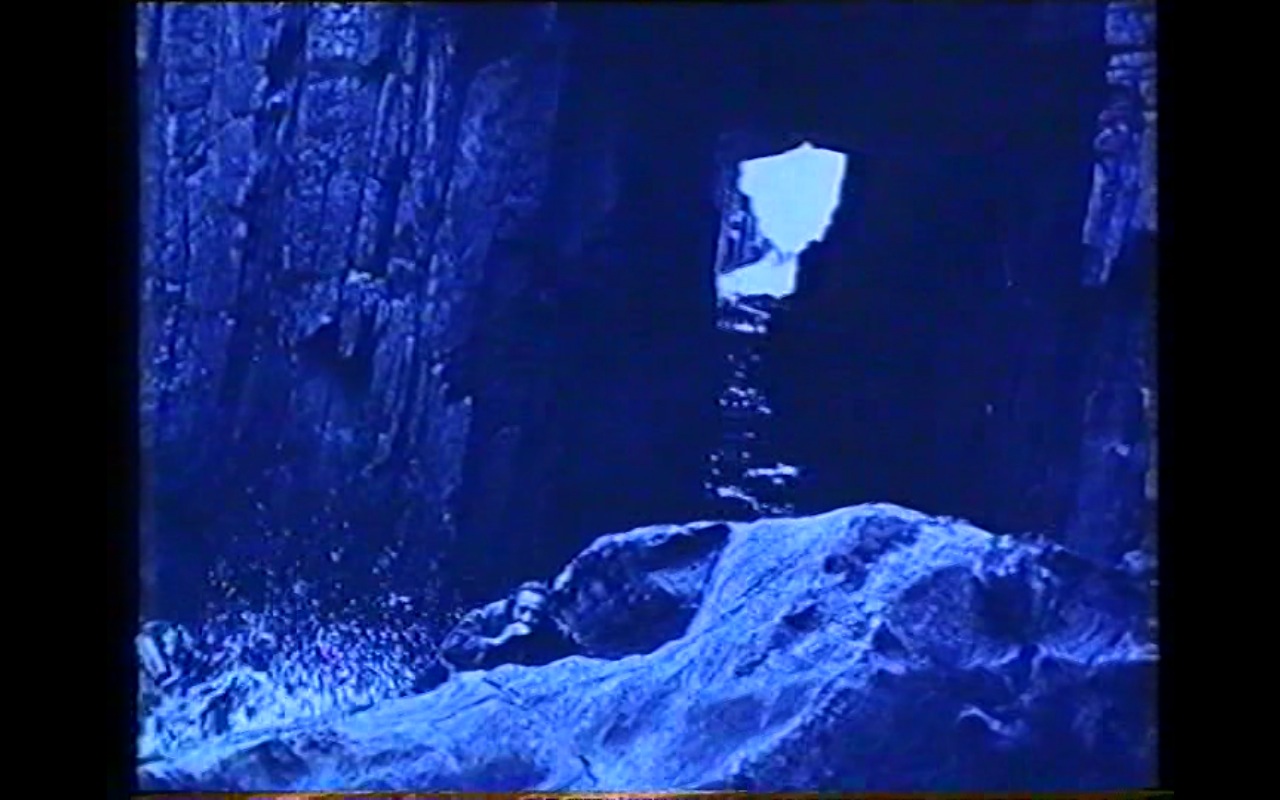

Fig 3: Remarkable Cave in For the Term of His Natural Life (Dawn, 1927)

The “picturisation” of For the Term of his Natural Life involved the “importation” of an American director and stars, and the prospect of attracting an international audience raised concerns about publicising Australia’s shameful convict history.[39] In his exploration of the production context for Dawn’s film, Michael Roe points out that in response to fears about tarnishing Australia’s image, studio spokespeople determined the film “would diminish aspects of the book which were most ‘gruesome,’”[40] meaning Pearce’s journey was relegated to a scenic sub-plot.

Fig 4: Remarkable Cave filming location (photograph by author, 2010)

While the landscape remained an adversary in the story, the film ultimately functioned as a showcase for the country’s attractions as newspapers reported at the time: “Mr. Dawn has taken the fullest advantage of the glorious scenery which Tasmania undoubtedly offers, and scenically speaking, ‘For the Term of His Natural Life’ on completion should be the best advertisement Tasmania has ever had.”[41] Among the first of the filmmakers that Susan Ward and Tom O’Regan would later describe as “long-stay business tourists,”[42] Dawn brought with him from America the sensibility of an outsider awed by the drama of Tasmania’s landscapes and sea cliffs and he obligingly opened his set to the public in support of a tie-in “Come to Tasmania” tourism campaign.[43]

Fig 5: Point Raoul filming location (photograph by author, 2010)

A large component of Dawn’s film—including the Macquarie Harbour scenes—was shot on the Tasman Peninsula, making Port Arthur the centre of gravity for the story even though Pearce himself was never incarcerated there. The Blowhole and Remarkable Cave feature prominently, the convict railway and Eaglehawk Neck kennels were painstakingly reconstructed, and the location used for Gabbett’s recapture was the site of a real sandstone quarry located at Safety Cove. Although it lies northeast of Pearce’s actual route, Dawn also filmed part of Gabbett’s journey at a location closely resembling Russell Falls, or Liffey Falls near Launceston. Clarke’s novel sees Gabbett head north from Port Arthur after his second escape and Dawn did shoot some footage in the Launceston area at Cataract Gorge[44] and under the bridge at Corra Linn, where he captured scenes of a hungry Gabbett on the lam.[45] Other than the final prison scenes, which were starkly lit sets constructed in Sydney, the film’s Gothic and Expressionist touches derive largely from the treatment of Gabbett and his journey, particularly the title card with a windswept graveyard bearing the text “For days—Gabbett had promised himself that his companion must sleep—and die.” Dawn repeatedly complained of Tasmania’s fickle light as he waited for the clouds to clear[46] so it is likely that the Gothic quality attributed to his film, while also present in the novel, was as much due to inclement weather and slow film stock as to stylistic intention.

Fig 6: Hells Gates, Macquarie Harbour (photograph by author, 2010)

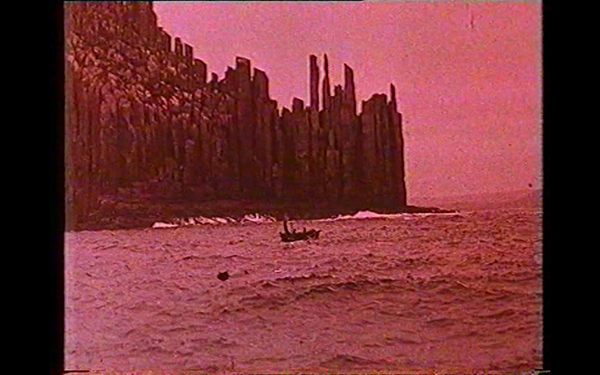

Clarke himself never actually visited Macquarie Harbour: his descriptions were based on James Ross’s Van Diemen’s Land Anniversary.[47] The novelist’s inventive treatment of the southwest has been augmented in screen adaptations, as is evident in Dawes’s attempt to escape by leaping into the roiling sea off Grummet Rock. Like the deceptively innocuous appearance of Hell’s Gates, the real Grummet Rock is a humble affair without spectacular sea cliffs. Dawn intended to spend a week in Macquarie Harbour shooting scenic footage “in order that every scene should reproduce the correct locale of the story.”[48] However, when scouting for locations he was struck by the peaceful beauty of the Gordon River and Macquarie Harbour. Reporting that the Gordon’s tranquillity was incongruent with the brutality of the penal colony and that the hazards of Hell’s Gates needed to appear “fearful and repelling,”[49] Dawn shot the lumber scenes in New South Wales and chose Cape Raoul’s jagged rocky spires at the southernmost tip of the Tasman Peninsula to represent Hell’s Gates.

Fig 7: Point Raoul location double for Hell’s Gates at the mouth of Macquarie Harbour in For the Term of His Natural Life (Dawn, 1927)

Dawn also alters the novel’s ending so that the unjustly sentenced convict Rufus Dawes and his love, the warden’s daughter Sylvia Vickers are last seen on a raft at sea after a storm destroys their ship. A glimmer of hope remains that they will survive their adventures on the “Fatal Shore”[50] and make a home together. This concession to “audience preference for an ending which promised that Rufus and Sylvia would live happily ever after”[51] is even more pronounced in the television version of For the Term of his Natural Life.

Fig 8: Point Raoul location double for Hell’s Gates at the mouth of Macquarie Harbor in the TV miniseries of For the Term of His Natural Life (Stewart, 1983)

The television miniseries was filmed largely in South Australia with inserts of paintings with intertitles to represent places such as historic Hobart town, Sarah Island, and Port Arthur, and cut-aways to signature Tasmanian landmarks like Frenchman’s Cap, which can be glimpsed from Macquarie Harbour on a clear day and was used as a navigation aid by escaping convicts. As in Dawn’s film, Cape Raoul is once more cast as Hell’s Gates and the Macquarie Harbour scenes are again filmed on the Tasman Peninsula. Despite its proximity to Port Arthur, Suicide Cliff at the Point Puer boys’ prison does not play itself; instead, along with the Grummet Rock sequences, these scenes are shot against the open water and pale limestone outcrops of South Australia’s Limestone Coast. Consequently, the quality of light differs markedly and such sequences lack the oppressive feel of the gloomy Point Puer woods.

In the miniseries Dawes sports an easy grin and a cheerful disposition, overcoming class barriers to become a landholder and achieve social justice on the mainland. This might be explained by Tulloch’s thesis that Australians eventually grounded their national identity “in a broadly accepted equalitarian social doctrine.”[52] Following the initial opposition between humans and environment, the landscape came to be seen as generative of identity: “The environmental conditions of the land produce the improvisation, intolerance of conventions and manly independence” and “signify the true Australian.”[53] The celebration of convict heritage during this optimistic period of nation-building in the 1980s was not to outlast the Bicentennial, however, and subsequent iterations of Pearce’s story were far bloodier and darker as Australia came to more fully recognise the injustices wrought by colonialism.

Dying Breed

Like the miniseries that sees Dawes live on past the end of Clarke’s novel, Dying Breed imagines the continuation of Pearce’s journey through more accessible terrain in Tasmania’s northwest. Haynes’s comment that representations of Tasmania’s insular island community feature “references to allegedly inbred, mentally defective individuals” in narratives wherein “the landscape became both symbol and catalyst of psychic and psychological debility”[54] could have inspired the script for Dying Breed. The movie begins with a map of Tasmania in which the rivers and arterial roads run red with blood. The action opens on Pearce’s second escape from Sarah Island, but instead of giving himself up he leaps into a chasm and is presumed dead. The ensuing story takes place in the present when four travellers, who are initially researching the Tasmanian Tiger, go in search of a missing Irishwoman who had run afoul of Pearce’s descendants when she visited the backwater town of Sarah, a fictional island community on the Pieman River. Victoria’s Dandenong Ranges doubled as Tasmania in some sequences and “township scenes were shot in Coal Creek Village in Korumburra in Gippsland,”[55] but much of the footage is shot in locations that Pearce might have travelled through, had his northward escape route been successful. After braving the Fatman Barge on the Pieman River crossing at Corinna (where historic graves concealed in the trees on the riverbank feature later in the film), the doomed travellers grope their way through disused mine shafts filmed in the Zeehan Spray Tunnel and stumble upon evidence of foul play at a woodman’s hut. Other shooting locations include the Murchison Dam spillway, a misty graveyard of sunken trees at Mackintosh Dam, and a dramatic death scene high on the rail bridge at Bastyan Dam near the end of the film.

Fig 9: Corinna River historic grave film location in Dying Breed (Dwyer 2008)

In Dying Breed, just as in For the Term of His Natural Life and other films in the cycle, the displacement of narrative settings such as Sarah Island and Hells Gates to shooting locations in more hospitable regions of Tasmania or even other states of Australia could produce what would, in a Gothic interpretation, be termed an “uncanny” landscape that seems at once familiar yet eerily strange. Ironically, such a Gothic reading is limited to “canny” spectators who have personal experience of the locations: for those who have not visited the places in which the story is set, the unsettling slippage between recognition and spatial uncertainty never occurs. Location doubles—like body doubles—are unnoticeable in a well-made film.

Fig 10: Zeehan spray tunnel film location in Dying Breed (Dwyer 2008)

While Dying Breed liberally deploys the iconography of the horror genre, a close relative of the Gothic, the filmmakers struggled with the darkness of the Tasmanian landscape in more than metaphorical terms. Thick vegetation, unpredictable weather, and the challenges of maintaining continuity when clouds scuttle across the sun make location shooting expensive and exhausting, frequently necessitating the displacement or substitution of Tasmanian landmarks. In recent years faster film stock and portable equipment have made working on rough terrain with inadequate light more achievable, but contemporary filmmakers still tell extraordinary tales about braving the elements in Tasmania. Regarding the mid-winter shoot that took place over a period of ten days when six hundred millimetres of rain fell and the crew was battered with eighty kilometre per hour winds and sleet, Dying Breed’s cinematographer Geoffrey Hall cheerfully notes: “I think we had terrific locations and the fact that we had such incredible weather in terms of rain and mist was just a total plus.”[56] The effect is certainly atmospheric and as Carly Millar observes, “the sheer beauty of the sweeping vistas and densely canopied woodland make the Tasmanian wilderness the real star of the movie.”[57]

Fig 11: Bastyan Dam rail bridge location for the denouement of Dying Breed (Dwyer 2008)

The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce

Unlike Dying Breed and adaptations of His Natural Life, Van Diemen’s Land and The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce are loyal to historical records regarding Pearce. Much of the dialogue and voice-over narration is drawn from Pearce’s confessions and these films convey a landscape in which humans are insignificant and cannibalism seems a desperate inevitability. Other than colonial exteriors and prison cells shot in New South Wales, Last Confession was filmed in the gentle landscape of buttongrass plains in Tasmania’s Central Lakes District, with King William’s Saddle gracing the horizon. Publicity for the production made much of the fact that locations on Pearce’s actual escape route were integral to the film, but the filmmakers resorted to shooting mountain footage atop Mount Wellington and forest scenery in Tahune near Hobart because it is virtually impossible to get production equipment into the Western Tiers. Other locations on Pearce’s route present different logistical difficulties: Loddon Plains where Bodenham was cannibalised has an unpleasant tendency to bog unwary travellers in waist-deep mud, and King William Valley is now inaccessible since being flooded for the Butler’s Gorge hydroelectric project in the 1950s. Of necessity many of the film locations are north or east of Pearce’s route, though it is likely he did pass near Derwent Bridge, which was the filmmakers’ base camp. The set for the Macquarie Harbour penal colony and Huon pine timber works was constructed at a bend in the river near Derwent Bridge, displacing Sarah Island yet again, and the scenic tourist lookout at Nelson Falls substitutes as a backdrop for the dangerous Franklin River crossing.

Fig 12: Sarah Island set at Derwent Bridge as seen in The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce (Rowland 2008)

Despite being an important narrative setting for all films in the Pearce production cycle, the mountainous terrain of Tasmania’s southwest wilderness thus far remains unfilmable, yet it is far from being an abstract, unknowable space devoid of value or history. Due to the contemporary transport corridors through which travellers and filmmakers move, the Central Highlands and the Lake District are becoming increasingly familiar and are acquiring what might be termed a misplaced spatial history associated with Pearce.

Fig 13: Sarah Island filming location at Derwent Bridge

Van Diemen’s Land

Albeit in a limited way facilitated by tourism infrastructure and Forestry Tasmania staff, Van Diemen’s Land has the distinction of being the first production to actually shoot Sarah Island footage in Macquarie Harbour itself and to film on the Gordon River where Pearce’s journey began. Although some locations such as Nelson Falls also appear in Last Confession, the Van Diemen’s Land aesthetic is quite different, cueing the audience to be as dispirited and overawed as the convicts when a summit is reached, revealing relentless mountainous terrain. When Pearce confides, “I wish meself death,” one can well imagine the desperation he felt. The film challenges audiences to consider what a person might do if after being sentenced to seven years of indentured servitude for stealing shoes, they were then underfed, isolated and brutally lashed, before fleeing into a cold, wet, and densely wooded forest so dark that it sustains minimal animal life and few edible plants.

Fig 14: Gordon River film locations as seen in Van Diemen’s Land (Auf der Heide 2009)

Accompanied by the first undercurrents of its nerve jangling sound design, Van Diemen’s Land opens to the chilling sound of howling wind. With a low drone the camera slowly descends into the wilderness along the deep green Gordon River where the trees appear like a dark fortress, the colour leeched away so the world seems bleak and hopeless. Pearce’s Gaelic voice-over describes this desaturated landscape as “the end of the world; a fine prison” and the cinematography reinforces the sense that the inhospitable, rugged wilderness stands sentinel over the remote prison colony. The close shots of tangled branches and the sense of being entrapped is captured by artful cinematography and editing, seamlessly intercutting footage of the convict work party with real Huon pine logs in the freezing waters of Macquarie Harbour with shots of the convicts pelting through the forest near Mariners Falls in the Otway region of Victoria. As the Tasmanian Search and Rescue team discovered, it is impossible to run through the dense undergrowth in Tasmania’s Wild Rivers region, hence the geographic place again cedes screen space to a distant location double.[58]

On location on the Gordon River itself, the camera seems to stalk the fugitives in Van Diemen’s Land; mounted high on a riverboat it glides down into ravines, never quite attaining a vantage point that reveals familiar landmarks or a pathway to freedom. The disembodied voice-over narration, the unsettling score, and the lurking camera convey a disturbing sense that the restless spirits of Pearce and his former companions haunt the landscape. When Thomas and Gillard argue that the Gothic “is the name of the ‘presence’ in Australian Cinema that seems firmly based in the malevolent undercurrent of the everyday,”[59] they could well be describing the menacing presence signalled by camera movement in Van Diemen’s Land, except that the dangers of this particular stretch of Tasmanian forest lie beyond the realm of quotidian experience.

Van Diemen’s Land begins and ends with spectral camera movements that suggest an inhospitable landscape, indelibly marked by violence and death and now inhabited by ghosts. Auf der Heide has said in interviews that Pearce’s story was long seen as a stain on Australia’s reputation so it was buried as a grisly sub-plot of a melodramatic romance in which the “darkness” of Tasmania’s wilderness “stemmed from the alienation and fear that the settlers and convicts experienced in the early days of British settlement… I wanted to give it the feel that ‘life’ wasn’t welcome there and that it was a harsh and brutal character. Pearce would then have to, in order to survive, become like the landscape.”[60]

Conclusion

The films in this study evoke a landscape experienced as a place haunted by the cruelties of convict history.[61] In each of its cinematic instantiations, Pearce’s journey is imagined as a debilitating trek through land so inhospitable that the fugitives resort to cannibalism to avoid starvation, yet the terrain also has the picturesque, unreal quality of an old oil painting. Auf der Heide states “The locations of the film had to represent Pearce’s state of mind so we could have an insight as to what he’s thinking. Each location visually represents the emotion he’s experiencing.”[62] The difficult river crossing can be read as entering the troubled waters of the soul, the sullen sky and creeping mists bespeak a dark confusion of the mind, the tangled paperbark forest whose peeling white bark is branded by deep shadows and bleeding sap signals Pearce is ensnared in a realm of moral turpitude. However, Tasmania is a living place that cannot be reduced to a metaphor for colonial prisons and the symbolic use of the land as a screen on which to project the protagonist’s psychic state is not the only way to interpret cinematic landscapes.

To return to the distinction between space and place, if space must be enculturated to become place and if pathways “structure experiences of the places they link,”[63] then the story of Pearce’s lonely journey plays an important mediating role, inscribing the untrammelled, uninhabited southwest corner of Tasmania as a textual space that can be vicariously experienced, valued for its historical, aesthetic, and ecological richness, and given a place in Australian culture. Yet Pearce’s “spatial story” has proven difficult to capture on screen and filmmakers have constructed a disorienting itinerary piecing his journey together with footage from different states and regions, resulting in what might be termed an “imaginative cinematic geography.”[64]

Having acknowledged the strengths and limitations of the Gothic as a framework of symbolic analysis, this article has approached spatial representation and perception from a geocritical perspective concerned with film and television as narrative art forms situated within production and reception contexts. Geocriticism moves beyond the analysis of an individual text’s treatment of space to “locate places in temporal depth” across an intertextual, multifocal study of representations of a region or territory.[65] As Haynes writes: “The process of relating to the Tasmanian landscape imaginatively required a context and the inscription of narratives and art to provide it with cultural resonances.”[66] The many screen versions of Pearce’s story give insight into both the regional patterns and historical locatedness that Westphal values and the cultural inscription of place that Haynes sees as crucial to enabling people to find their place in the landscape. The cannibal convict film cycle demonstrates not only how representations of Tasmania are shaped by production logistics, but also that such practical and economic constraints intersect with politically charged sensitivities about place, history, and identity to produce a vicarious cinematic experience characterised by imaginative and dislocated perceptions of the landscape.

[1] Marcus Clarke, His Natural Life (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1878), accessed November 15, 2011, http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/clahisn.

[2] Carly Millar, “The Horror, the Horror: Tasmania’s Cannibal History on the Silver Screen,” Metro 159 (2008): 18.

[3] Yi-Fu Tuan, “Place: An Experiential Perspective,” Geographical Review 65 no. 2 (1975): 152.

[4] Bertrand Westphal, foreword to Geocritical Explorations, edited by Robert T. Tally (Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2011), xii.

[5] Edward Soja, Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory (London: Verso, 1989).

[6] Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991).

[7] Derek Gregory, Geographical Imaginations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994).

[8] Yi-Fu Tuan, Place and Space: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977).

[9] Tuan, Place and Space, 6.

[10] Christopher Tilley, A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1994), 27.

[11] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 115.

[12] See, for instance, Allison Craven, “Tropical Gothic: Radiance Revisited,” e-tropic: Electronic Journal of Studies in the Tropics no.7 (2008): http://www.jcu.edu.au/etropic/ET7/CravenRadiance.htm; Graeme Harper and Jonathan Rayner, eds., Cinema and Landscape (Bristol: Intellect, 2010); Anthony Lambert, “(Re)Producing Country: Mapping Multiple Australian Spaces,” Space and Culture 13 no. 3 (2010) 304–314; Martin Lefebvre, ed., Landscape and Film (New York: Routledge, 2006); Martin Lefebvre, “On Landscape in Narrative Cinema,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 20 no. 1 (2011): 61–78; Christopher Lukinbeal, “Cinematic Landscapes,” Journal of Cultural Geography 23 no. 1 (2005): 3–22; Robert Shannan Peckham, “Landscape and Film,” in A Companion to Cultural Geography, ed. James S. Duncan et al., (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004), 420–429; Catherine Simpson, “Shifting from Landscape to country in Australia, after Mabo,” Metro 165 (2010): 88–93; Jane Stadler and Peta Mitchell, “Never-Never Land: Affective Landscapes, the Touristic Gaze and Heterotopic Space in Australia,” Studies in Australasian Cinema 4 no. 2(2010): 173–87.

[13] Tim Flannery, introduction to Watkin Tench’s 1788, by Watkin Tench (Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 1996), 11.

[14] Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore: A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787–1868 (London: Harvill Press, 1987), 220.

[15] Simon Morris, “When Driven by Hunger,” Australian Geographic, June 29, 2009, http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/when-driven-by-hunger.htm.

[16] Morris, n.p.

[17] Hughes, 372.

[18] “Picture Studio Gossip,” Queanbeyan-Canberra Advocate, December 9, 1926, 4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article31691101.

[19] Hughes, 375.

[20] Paul Collins, Hell’s Gates: The Terrible Journey of Alexander Pearce, Van Diemen’s Land Cannibal (South Yarra: Hardie Grant Books, 2002), 113–14.

[21] Clarke, 99–100.

[22] Katherine Biber, “Colonialism and Cannibalism,” Sydney Law Review 27, no. 4 (2005): 624–25.

[23] Mikita Brottman, “‘There never was a party like this. . . !’ Blood Feast and the Primal Act of Cannibalism,” Continuum 9, no. 1 (1996): 32.

[24] Millar, 21.

[25] Gerry Turcotte, “Australian Gothic,” in The Handbook of Gothic Literature, ed. Mulvey Roberts (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998), 11.

[26] David Thomas and Garry Gillard, “Threads of Resemblance in New Australian Gothic Cinema,” Metro no. 136 (2003): 36–40; 42–44.

[27] See Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka, The Screening of Australia, vol. 2 (Sydney: Currency Press, 1988), 51.

[28] Emily Bullock, “Rumblings from Australia’s Deep South: Tasmanian Gothic On-screen,” Studies in Australasian Cinema 5, no. 1 (2011); Jonathan Rayner, “Gothic Definitions: The New Australian Cinema of Horrors,” Antipodes 25 no. 1 (2011): 91–97; John Scott and Dean Biron, “Wolf Creek, Rurality and the Australian Gothic,” Continuum 24, no. 2 (2010): 307–322.

[29] Roslynn Haynes, Tasmanian Visions: Landscapes in Writing, Art and Photography (Sandy Bay: Polymath, 2006), 219.

[30] Jim Davidson, “Tasmanian Gothic,” Meanjin 48, no. 2 (1988): 310.

[31] Bullock, “Rumblings,” 78.

[32] Scott and Biron, 317.

[33] Hughes, 47.

[34] Pete Hay, “A Phenomenology of Islands,” Island Studies Journal 1, no. 1 (2006): 21.

[35] Haynes, 222.

[36] Turcotte, 10.

[37] Tuan, “Place: An Experiential Perspective,” 162.

[38] John Tulloch, Legends of the Screen: The Narrative of Film in Australia 1919–1929 (Sydney: Currency Press, 1981), 346.

[39] Tulloch, 306–14.

[40] Michael Roe, “Vandiemenism Debated: The Filming of ‘His Natural Life,’ 1926/ 7,”

Journal of Australian Studies 24 (1989): 39.

[41] “An Australian Film,” Examiner, September 28, 1926, 5, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article51365386.

[42] Susan Ward and Tom O’Regan, “The Film Producer as the Long-Stay Business Tourist: Rethinking Film and Tourism from a Gold Coast Perspective,” Tourism Geographies 11 no. 2 (2009): 214–32.

[43] “Tasmania Invites You To Share Her Charms!” The Mercury, September 9, 1926, 14, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article29458084.

[44] Roe, 46.

[45] “An Australian Film,” 5.

[46] Dawn is reported to be struggling to capture good footage in poor light in newspaper articles including Percy Curtis, “‘On Location’ with Australia’s Movie Colony,” Sunday Times, September 26, 1926, 11, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58249879; “For The Term of His Natural Life,” The Mercury, September 8, 1926, 10, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article29457893; “An Australian Film,” 5.

[47] Lloyd L. Robson, “The Historical Basis of For the Term of His Natural Life,” Australian Literary Studies 1 (1963): 106.

[48] “For the Term,” 10.

[49] “Cinematograph Party Visit to West Coast,” The Mercury, September 27, 1926, 2.

[50] Hughes.

[51] Roe, 36.

[52] Tulloch, 349.

[53] Tulloch, 348.

[54] Haynes, 219.

[55] Millar, 19.

[56] “Dying Breed Production Notes,” last modified 2008, http://thecia.com.au/reviews/d/images/dying-breed-production-notes.rtf (Accessed November 15, 2011): 7.

[57] Millar, 19.

[58] The issue is not so much that a film is shot in an “inauthentic” location far from where the historical narrative actually unfolded, for all film landscapes are but representations and interpretations of place. Rather, here and elsewhere, the question is how the choice of a location double affects the qualitative construction of a sense of place. While the landscape aesthetic is similar, the semantic and affective charge of the Otways differs from that of Tasmania’s southwest. The more open Victorian location creates space for some light-hearted moments in the film that would not have been possible had the forward momentum of the plot stalled to show convicts slogging through impenetrable scrub.

[59] Thomas and Gillard, 44.

[60] Emily Bullock, “Strange Silence in Van Diemen’s Land: An Interview with Jonathan Auf der Heide, Director of Van Diemen’s Land,” Metro Magazine 162 (2009): 42.

[61] As historian Maria Tumarkin writes in her analysis of ideas about trauma and survival and their effects on landscapes and communities, Tasmania—particularly Port Arthur and Macquarie Harbour—can function as a site onto which anxieties about colonial savagery and Australia’s national origins can be projected and thereby expelled from the mainland imaginary (199). Maria Tumarkin, “‘Wishing you weren’t here…’: Thinking about Trauma, Place, and the Port Arthur Massacre,” Journal of Australian Studies 25.67 (2001): 196–205.

[62] Bullock, “Strange Silence,” 43.

[63] Tilley, 30.

[64] Peta Mitchell and Jane Stadler, “Imaginative Cinematic Geographies of Australia: The Mapped View in Charles Chauvel’s Jedda and Baz Luhrmann’s Australia,” Historical Geography 38 (2010): 26–51.

[65] Westphal, introduction, xiv.

[66] Haynes, xii.