One of the core values of the photograph as a visual object of communication is its temporal, emotional and connotative variety. In relation to motion and speed, the photograph, although essentially still as an object, frequently strains against its static boundaries, so that it can be encountered emotionally (as a process) across shifting temporal modes of spectatorial perception and reception, as both a slow, contemplative, or a fast, instinctive, visual experience. It is both instantaneous and persistent in duration enabling it as ‘montage’ to record the present and remember the past, since as soon as it captures the here and now it immediately recedes into history. Perhaps most pertinently, the photograph works to extend our experience of time, delaying the degradation of past events and experiences, while working to trigger, prolong, and in some instances, to transform memory.[1] At the same time, while the photograph has operated as an object of proof and evidence, it has also always been open to manipulation, and thus to query and this concept of photographic ‘doubt’ has increased in recent years, reaching an apex during the mid-1990s around cinema’s centenary.[2] The rise of digital film and photography, coupled with a growing popular awareness of the ease of photographic manipulation via a multitude of media, expanded the idea of the photograph as a mutable object and resulted in a loss of confidence in relation to the actuality of the photographic image. Negatives and prints were, and continue to be, replaced by intangible, ethereal data, causing increasing levels of mistrust regarding the status of the photograph as both a factual document and a genuine record of the past.[3]

At the heart of these discussions regarding the death of photography and the ‘loss of the real’ in the digital age lies an inherent nostalgia for the optical and ontological qualities of the analogue, black and white photograph. There is a longing not for the past, but for a past mode of representation. Contemporary critics seem to be mourning not the loss of actual photographic realism, but rather the emotional loss of a kind of imagined, fetishised photographic truth and aura, elevated by Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes, the most visible element of which is a monochrome palette.[4] Pam Cook has defined nostalgia as “a state of longing for something that is known to be irretrievable, but is sought anyway”.[5] In this context, however, the factual and realistic photographic truth of the monochrome past that seems to be longed for never actually existed. The black and white image is a constructed version of reality. It envisions a past that has been stripped of colour, a past that has been re-imagined in form and line, in contrast and shadow.

Due to photography’s mechanical ontology, the content, form, and style of the images that are preserved shift apace with contemporary fashion and technological development, and as a result, as photographic technology develops, so too does the way society remembers the past. In this dialectic, technical limitations become cultural connotations. The technological break that occurred in visual culture when colour was introduced on a large scale resulted in the black and white image becoming historically connotative of a specific period of the past. In other words, all forms of photography from photojournalism, to art, to advertising, (and indeed its relative mediums, television and cinema), are part of the creation of an image-based, technologically-driven collective memory through which history is filtered, of which the most overt visual signifier of the past has become the presentation of the world in black and white.

The predominance of the black and white photograph in representations of the past, (even though colour photography had been experimented with as early as the 1840s), is due to a number of factors related to the cultural dissemination and interpretation of photographs and images. Firstly, although the general public had been able to have images tinted, dyed and in some cases printed in colour on paper by photographic production companies prior to the 1940s, it was not until 1947 that colour photography became available to professionals and keen amateur photographers en-masse.[6] The combination of faster colour film, with the introduction of smaller, more light-weight and portable 35mm cameras that became available to (predominantly American and European) interested amateurs in the late 1930s and 1940s “enabled amateur photographers to capture the world in true colours for the first time, defining a new way of seeing.”[7] For photojournalists, however, especially those working in the late 1940s and 1950s, even though colour was available, monochrome remained the dominant mode through which a seriousness of purpose could be combined with artistic quality. In a practical sense, monochrome was used because black and white cameras could be operated faster, and the images that they produced could be developed and printed more easily than their colour counterparts. Their focus was sharper, the image produced was crisper, and they required less light to obtain more accurate pictures. Eventually, however, practical concerns became aesthetic preference so that, until recently, documentarians and photojournalists working in colour were criticised for making photographs look too much like paintings, negating their socially concerned heritage as exemplified in the monochrome work of Lewis Hine.[8] Consequently it seemed that the factual, informative image, the index, could only be truthful, respected and fully socially-concerned if it appeared in black and white. Furthermore, those photographers seeking to distinguish photography as an artistic medium separate from painting, sought to work exclusively in black and white, not only because it distanced them from those artists working with a palette and a brush, but also, as Vilém Flusser argues, because black and white photographs “…more clearly reveal the actual significance of the photograph, i.e. the world of concepts.”[9] Flusser describes a figurative world that eschews the often-confusing complexity of colour in favour of the more clearly delineated structures of form, contrast and light that operate at the heart of the monochrome image. These two cornerstones of the black and white photograph; a photojournalistic drive to record and report on the one hand, and a desire to distinguish the medium both as art and as distinct from painting, on the other, have created a photographically remembered past that in many cases, and until recently, has resulted in an absence of colour references within historical cultural memory.

Although it was launched in America in the mid-1950s, the relative expense of colour television sets meant that it wasn’t until the late 1960s that colour reached viewers en-masse. The situation was echoed in Europe when in 1967 colour television was launched on BBC2 in the UK, flooding at first hundreds and then thousands of homes with news, sport and current affairs programmes in full colour for the first time.[10] Until this point, only in the cinema had most audiences experienced vibrant and luminous colour photographic images in motion. Thus in addition to the heritage of photojournalism, the televisual presentation of news imagery and current affairs programs in black and white until the 1960s combines with the association of colour photography with the fantasy and artifice of the cinema to create a “memory” of the pre-1960s past as a black and white era. Furthermore, this legacy has led, somewhat paradoxically, to the association of realism and artistry with the black and white image.

It is because of this black and white photographic heritage that some contemporary films have chosen to represent the past with a monochrome palette; an aesthetic decision that is often visualised via post-production transfers from original colour stock with the help of state-of-the-art digital techniques. Films such as Good Night, and Good Luck (George Clooney, USA 2005), The Good German (Steven Soderbergh, USA 2006), The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke, Austria 2009) and The Man Who Wasn’t There (Joel Coen, USA 2001), all seek in some way to appeal to the black and white transformation of personal and cultural memory, so that the versions of the past that they represent appear more truthful, serious and artistic, so that the imagined history represented in the film replicates photographic and televisual history, thus reaffirming the existence of the black and white past. At the same time, on the rare occasions when contemporary cinema uses black and white cinematography to represent the present (or an alternate, imaginary present) in a film like Sin City (Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller, USA, 2005), it does so because of a wish to not only nostalgically re-engage with the artistic nature of the photographic past, but to also reinvent the present through the use of new digital technologies that can transform both our spectatorial gaze and our emotional relationship to black and white images, creating an amalgamation of the previously differentiated photographic, cinematic and digital image. These films were made in monochrome because they were inspired by both a photojournalistic documentary aesthetic and the prevalence of black and white media images (on television, and in advertisements) from the past, while they are simultaneously influenced by a sense of emotional nostalgia for noir-ish film aesthetics and the grit and grain of low budget 1960s cinema. What emerges is the sense that the black and white past, as Pam Cook and Celia Lury have argued with regard to media-based reproductions, is a prosthetic construct, a manipulated version of history built with layers of imagery that continues to be reinforced in the present by new films that seek to authenticate their narratives with a monochrome palette.[11] In order to understand how the actual past is visualised in memory we must first look at the way that it has come to be represented in contemporary fictional versions of history. What emerges is a presentation of the past that is bound up in black and white televisual, filmic and photographic tropes that aim to represent history, not through actual realism, but through the remembered emotive realism of the image.

Re-Imagining Monochrome in the Digital Age

The Man Who Wasn’t There aims not for historical accuracy but for a mood, an evocation, and an atmosphere that is constructed and filtered through an artistic combination of the remembered literary, photographic, televisual and filmic past. As the film’s cinematographer Roger Deakins explains, “I don’t know how consciously I was influenced by the old, classic black-and-white movies of the 40s, though I did watch quite a few…It was never a conscious lift, but it’s something you just absorb, all those influences coming together.”[12] In a similar way, films with a contemporary setting like La Haine (Kassowitz, France 1995), Tetro (Coppola, USA 2009) and Coffee and Cigarettes (Jarmusch, USA 2003) can be read as the product of monochrome photo-filmic osmosis, whereby black and white images from the past have infiltrated not only the way that the past is remembered, but also the kind of artistic and cultural value that has become attached to the black and white image in the present. Films like The Man Who Wasn’t There work as an example of the malleability of cultural memory, of the impact of black and white representations of the past on contemporary filmmaking, and of the potential power of images to transform the way historical reality is remembered, imagined, and established in the present. Perhaps most importantly, through their presentation of the past as black and white, contemporary monochrome films offer an overtly constructed version of history, and as a result they engage directly with systems of authenticity, artifice and spectatorial expectation. Pam Cook’s assertions in Screening the Past that media-driven reconstructions of the past help us to understand and evaluate our relationship with history illuminates one of the fundamental structures operating at the heart of cultural memory.[13] Her work suggests that in addition to eyewitness accounts, history is also lived and remembered through a shared sense of nostalgia for a past event, as it has been constructed, disseminated and communicated across a variety of media. Cook also proposes that this kind of media-induced memory must not necessarily be thought of as artificial, and consequently, as a negative development. Instead, in order to understand the form and function of memory more fully, new discussions must be undertaken that allow room for the suggestion of not only multiple versions of history, but also multiple versions of positive historic nostalgia. Within these parameters, it is the frequent, default, nostalgic representation of the past in black and white that becomes visually most predominant.

Since the mid-1990s, however, when post-produced black and white cinematic images emerged, some critics have argued that digital monochrome lacks the nostalgic authenticity evoked by analogue film. This revolutionary computer-generated monochrome image in which film is either stripped of colour in post-production, or ‘painted’ with black and white digital effects, for some eschews both the grit and grain of photojournalistic realism and the wistful dream-like recollections of the photographically-inspired reconstructed past. Instead, the digital monochrome film presents the spectator with a new way of understanding and valuing the black and white image that uses both technological advances and more traditional systems of visual craftsmanship to complicate contemporary modes of seeing. Many critics are, however, sceptical of both the quality and the emotional authenticity of the digital black and white image. This criticism of the transformation of monochrome is bound up in cultural and critical anxieties surrounding the relatively recent conversion from analogue to digital film, a switch that, as Garrett Stewart has noted, is as much characterised by a loss of the ‘real’ as it is by a return to more traditional techniques of image construction.[14]

Some critics have viewed this shift from photographic replication to artificial creation as responsible for a loss of image-value. One of the key criticisms of The Good German was its reliance on overly constructed, visually inferior digital monochrome and the resulting loss of nostalgic ‘aura’. At the start of the film Soderbergh cuts from stock footage of a demolished Berlin to his black and white reconstructed aircraft hangar. Although the transition between the two technologies is reasonably smooth and almost imperceptible, it is the shift in frame rates and the resultant loss of the ‘flicker’-effect that most overtly distinguishes between the two techniques, since the flicker acts as a visual marker of a historical (and thus, perhaps more authentic) cinematic time period. Although (apart from a number of instances of actual documentary footage), the rest of the film continues without this ‘flicker’, it is Soderbergh’s apparent desire to distance his representation of the past from the aesthetics of actual historical documentary footage that has led to criticism of the film’s use of the black and white image. Graham Fuller notes that, “As an artefact of the digital age, the film is counterintuitive: its stark chiaroscuro suggests, not unpleasingly, a bad film-to-video transfer.”[15] While Amy Taubin has gone so far as to question whether the film is even black and white at all:

To be precise, The Good German is not a black-and-white film, but a black-and-white looking-film that’s shot on colour stock and either chemically drained of colour during processing or digitally drained during post-production. For a variety of reasons—one of them Soderbergh’s preference since Traffic for an image in which the bright parts are almost blown out—it looks less like a 1940s film as it would have looked in the 1940s and more like the kind of degraded dupe of such a film we’re used to seeing today.[16]

As well as drawing attention to The Good German’s postmodern position as a film that uses contemporary digital effects in an attempt to evoke the past, Fuller’s observation emphasises the sense that some digital black and white images corrode cultural memory with their overt artificiality. Similarly, Taubin’s comment that the film is a “degraded dupe”, questions the film’s attempt at any kind of digital verisimilitude, and emphasises the importance of chemical black and white authenticity in the representation of serious fictional versions of the past. It seems that when contemporary cinema represents the past, in order to be understood by some critics as authentic, it must use techniques that avoid digital manipulation and spectacle. Black and white images of the kind elevated by Taubin are perceived as less constructed and aestheticised, and thus more capable of being reverential to their subject matter. In this scenario the chemical monochrome image becomes imbued with a sense of purity, worthiness and historical importance, as though it can in some way directly speak of, and thus more accurately remember, the past.

Recently, however, digital techniques and the talents of the technicians involved in manipulating the image have improved so that in certain circumstances it is increasingly difficult to tell if a film has either been shot on monochrome stock or transformed into black and white in post-production. Due to the insufficient sensitivity of black and white film stock to low light levels, Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon (Fig. 2) was filmed in colour and converted, a fact that is belied by the film’s densely lustrous monochrome imagery that intentionally recalls the austere 1920s and ‘30s portrait photography of August Sander.[17] As Haneke himself explains regarding his decision to use black and white imagery, “…the viewer knows the story is not ‘reality’ but a memory, an artefact created by someone. I felt that was necessary because this was a film set in the past. It’s the same thing with using black and white rather than colour—it reminds you it’s not reality you’re seeing but something artificial.”[18] For Haneke, digital black and white cinema adds artistic value since it highlights the ability of the chemical monochrome image to transform coloured reality into the constructed nostalgia of form and shadow.

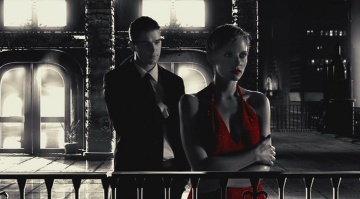

In Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller’s noir-inspired Sin City, the on-screen relationship between monochrome imagery, nostalgia and artifice is further complicated with the addition of both comic book inspiration and new computer generated technology that divorces the black and white image from its connections to photojournalistic truth and instead artistically manipulates monochrome as though it were expressive, painterly colour. The film uses digital chiaroscuro black and white cinematography and instants of luscious, saturated, painterly colour to re-imagine three of Frank Miller’s iconic graphic novels: That Yellow Bastard (1996), The Hard Goodbye (1991-2) and The Big Fat Kill (1994-5), for a postmodern cinema audience.

Almost everything in the film was shot on green-screen, allowing Rodriguez and Miller to use small, highly-controlled sets where the actors interact intimately with each other, before transforming the material in post-production so that Miller’s signature comic style of moody, graphic lighting and fantasy cityscapes could be realised with the help of state-of-the-art computer technology. A limited, predominantly monochrome environment mirrors the limited emotional existence of the characters in which polarised boundaries of good and evil are still very much enforced.[19] When colour does appear, it jumps out of the monochrome world, saturating the coloured object, body part or excretion of choice with intense, vibrant hues that look like splattered paint. Flashes of emotional colour, especially anger or intense love are rendered only sparingly, most often visualised as brooding, vampish red on women’s lips that recall the blood that pumps out of the bodies of the broken, beaten anti-heroes (Fig. 3).

However emotionally invigorating these accents of colour are, the most intense moments in the film are signalled not with colour, but with a return to a purely graphic world that is devoid of almost all detail, except the fundamental dialectic between black and white. When Dwight nearly drowns in oil in The Pitt after trying to hide the bodies of the policemen that the prostitutes of Old Town have accidentally killed, he slips under the surface and loses consciousness and the filmic world shifts from detailed monochrome and colour to stark black and white, so that he appears like a white stencilled figure floating in a sea of black tar. In the final moments of That Yellow Bastard when Hartigan finally decides to end it all and shoot himself in the head, again the film reverts to collage-like white images on a black background, as the bullet exits his head and he falls to the ground surrounded by graphic mounds of snow (Fig. 4). CGI makes the visual and aesthetic quality of monochrome different. It divorces the image from its chemical referent, distancing cinema and its association to the historical black and white of the photograph from its connection with factual record, and imprinting the image on screen with the painterly, malleable qualities of art and design. Instead of referencing the mechanical, the image looks and feels hand-made, so that in Sin City, the use of both CGI and digital techniques seem to push the image past the realm of the photo-cinematic and towards a new kind of visual spectacle that can visually re-imagine graphic forms and historical literary genres as much as is it can display an image with light.

The films discussed here point to the way that cultural memory has been constructed not only through paper documents and eyewitness accounts, but also primarily through a range of photo-filmic imagery that works to record and yet also remember the past through the image itself. The desire to document and preserve history is most evident in contemporary black and white films that directly recall the serious intent, yet partial capacity of black and white photojournalism to report the world in form and shadow, turning the monochrome photographic past into a cinematic fetish. These films continue to use black and white cinematography to transform personal and cultural memory through a sense of sombre historical authenticity, while simultaneously reminding the spectator of the irrepressible impact of photography on the formation of cultural memory. As Celia Lury notes, “The assumption here, then, is that the photograph, more than merely representing, has taught us a way of seeing (Ihde, 1995), and that this way of seeing has transformed contemporary self-understandings.”[20] The direct, oppositional qualities of the monochrome image are used to not just nostalgically recall the past, but to also address more modern concerns regarding the nature of social and cultural memory on a graphic visual level, while advances in digital technology indicate a sophisticated, more complex, somewhat plastic return to hand-crafted techniques that begin to mark the black and white image as a non-indexical sign. In this way digital black and white cinematography can be read as a shared visual language that helps to immediately situate the spectator in a recognisable time period, while at the same time it works as a tool through which contemporary issues of authenticity, artifice and nostalgia can be explored. Ultimately, through these monochrome palettes, and their intertextual photo-filmic style of referencing and remembering history, the ‘remembered realism’ of images in contemporary cinema becomes the most real, most emotive, and most evocative version of historical remembrance.

Endnotes

[1] See Regis Durand, ‘How to See (Photographically)’ in Patrice Petro (ed) Fugitive Images: From Photography to Video (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995) 147; David Campany, Art and Photography (London: Phaidon, 2003) 20; Mieke Bal, ‘Sticky Images: The Foreshortening of Time in an Art of Duration’ in Carolyn Bailey Gill (ed) Time and the Image (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2000, pp. 79-99) 80 and Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, (London: Vintage, 1980/2000) 82.

[2] As early as 1858 Henry Peach Robinson tricked many into believing that his Albumen photograph Fading Away was a single image, when in fact it was a composite of five negatives (Fig. 1).

[3] See Martin Lister (ed), The Photographic Image in Digital Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1995) 1. Lister cites Hughes, ‘No Longer in the Eye of the Beholder’ in The Guardian (4th September, 1990), Mathews, ‘When Seeing is Not Believing’ in the New Scientist (October, 1993, p. 13-15), and Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992).

[4] See Susan Sontag, On Photography (London: Penguin, 1977/2002) 140-1 and Barthes, 81.

[5] Pam Cook, ‘Rethinking Nostalgia: In The Mood For Love and Far From Heaven’ in Pam Cook, Screening the Past: Memory and Nostalgia in Cinema (London and New York: Routledge, 2005, pp.1-22) 3. Annette Kuhn similarly defines nostalgia as “…a very specific type of memory: nostalgia, a bittersweet longing for a lost or otherwise unattainable object.” Annette Kuhn, An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory (London: IB Tauris, 2002) 212.

[6] See Alma Davenport, The History of Photography: An Overview (Boston and London: Focal Press, 1991) 25.

[7] Pamela Roberts, A Century of Colour Photography: From the Autochrome to the Digital Age (London: André Deutsch, 2007) 102.

[8] Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History, (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2002) 405.

[9] Vilém Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography (London: Reaktion Books, 1983) 43.

[10] See Albert Abramson, The History of Television, 1942 to 2000 (North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003)

[11] See Cook, ‘Rethinking Nostalgia’, 2005, 2-3 and Celia Lury, Prosthetic Culture: Photography, Memory, Identity (London and New York: Routledge, 1998) 3.

[12] Roger Deakins in Philip Kemp, ‘Dead Man Walking’ in Sight and Sound (Vol. 11, Issue 10, October 2001, pp. 12-15) 14.

[13] Cook, 2-3.

[14] Garrett Stewart, Frame/d Time: Toward a Postfilmic Cinema (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2007) 55.

[15] Graham Fuller, ‘The Good German’ review in Sight and Sound (Vol. 7, Issue 13, March 2007, pp.58-60) 60.

[16] Amy Taubin, ‘Degraded Dupes’: Steven Soderbergh’ in Sight and Sound (Vol. 17, Issue 3, March 2007, pp.26-9) 28.

[17] See Geoff Andrew, ‘The Revenge of the Children’, interview with Michael Haneke and in Sight and Sound (Vol. 19, Issue 12, December 2009, pp. 14-17) 17.

[18] Haneke, 17.

[19] Aylish Wood, ‘Pixel Visions: Digital Intermediates and Micromanipulations of the Image’ Film Criticism (Vol. 32, No. 1, Fall 2007, pp. 72-94) 72.

[20] Lury, 3. Lury cites Ihde, D, ‘Image technologies and traditional culture’ in Feenberg and Hannay (eds) Technology and the Politics of Knowledge (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995, pp. 147-159).

Created on: Sunday, 7 November 2010