Abstract

The New American Cinema of the 1960s differed from conventional models of filmmaking in many ways, embracing chance, roughness of physical execution, an impoverishment of technical and financial facilities, but also freeing the filmmakers to create personal films that reflected their lives, their sexuality, and their social beliefs. The “actors” in these films are really performing themselves, even if they follow a script; “performance” in experimental films of the 1960s was really an extension of each actor’s personality, and often, actors were left to their own devices, without traditional direction, during the production of a film. This essay discusses some of the key films of the era, along with the directors and performers who created them.

……

Acting and performance styles in experimental films are many and varied, but all rely to some degree on the force of individual personality to relate to the film’s intended audience. The nomad bikers in Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (USA 1963), for example, are essentially performing themselves for the camera as part of the normal daily catalogue of ritualized behavior, whereas Gerard Malanga as Victor, the Victor in Andy Warhol’s Vinyl (USA 1965), working from Ron Tavel’s script, delivers an exaggerated, over-the-top “declamatory” performance that was partly the result of Warhol’s refusal to let the actors rehearse, so that Malanga was forced to read much of the script from enormous cue cards during the filming, essentially reading the scenario for the first time. Since all acting contains a certain element of theatricality, the strategy in experimental cinema depends either on complete improvisation (as in the case of Taylor Mead in Ron Rice’s free form feature film The Flower Thief [USA 1960]), or else upon a stylized sensibility that seems to bring to the forefront the essential artificiality, or performative nature, of acting.

Often, actors in experimental films are friends of the director, or else stage actors working on the fringe of performance arts, and so there is a strong sense of exploration and uncertainty in experimental filmic acting styles, since in many cases, the film is a combined voyage of discovery for both the performer and the director alike. Using examples from the works of such artists as Andy Warhol, Ron Rice, Jack Smith, Gunvor Nelson, Gerard Malanga and others, I’ll attempt to examine the question of what defines “performance” in the world of experimental cinema, and the many ways in which it manifests itself in some signature works of this multifaceted genre.

In the early 1960s, before the specter of AIDS consciousness closed off the body into a site of dis/ease, American experimental filmmakers were more intent on exploring the limits of their physical/mental existence than on more formalist questions of filmic structure and syntax, which would dominate the American avant-garde in the 1970s and 80s. All of these filmmakers shared one thing in common: a highly personal and deeply felt vision of a new and anarchic way of looking at film and video, fueled by the inexhaustible romanticism of the era and the fact that film and video were both very “cheap” mediums in which to work during the 1960s.

The Flower Thief is a good example of the essence of performativity as content and as the informing structure for creating a finished cinematic work. Produced to final, optical sound print for considerably less than $1,000 on outdated black and white film stock (specifically, leftover aerial gunnery film in 50 ft. cartridges from World War II, donated at the last minute, curiously, by the notoriously cost-conscious Hollywood producer Sam Katzman) the film follows Taylor Mead, the Chaplin of the 1960s underground, on a series of picaresque adventures in and around San Francisco. The film has little plot, and needs none; the title derives from a random incident in which Mead steals a flower from a street vendor, then fantasizes that the police are about to arrest him for his crime. Escaping down the steep San Francisco streets in a Radio Flyer child’s wagon, desperately clutching his much-abused teddy bear, Mead is at once pathetic and endearing, projecting an image of holy foolishness on the screen.

As the film progresses through its 75-minute running time, Taylor Mead interacts with groups of roving beatniks, school children, jazz musicians, and North Beach hustlers to create a portrait of a man unfettered by the constraints of society. The film’s construction is equally anarchic, incorporating as it does light flares, punch holes, mere fragments of film edited together to form a semi-coherent whole, and, at times, entire 50’ reels of film unedited, straight from the camera. The soundtrack for The Flower Thief is, appropriately enough, a mixture of scratchy old records and Beat poetry; no attempt at image/sound synchronization is made. The soundtrack is every bit as rough in its execution as are the images; it is simply the gathering of Mead’s acts of performance that interests Rice above all other formalist concerns. Considered perhaps the most uncompromising and genuinely avant-garde feature film of the very early 1960s, The Flower Thief is a paean to the plight of the common man in a world that is both unresponsive and unyielding.

This motivated extravagance extended to Rice’s other films, most notably Chumlum (USA, 1964), which starred Mario Montez, Gerard Malanga and Jack Smith – more on these widely variant personalities later in what René Micha in Les Temps Modern described as “an infinite spectacle, superimposing bodies swinging in hammocks, back and forth through gossamer draperies that slow the movements, and suspend them on the edge of the abyss” (as qtd. in FMC Catalogue No. 4, 125). Shot in ravishing color, the film is an indolent spectacle of pleasure run rampant, existing in a world in which the only pursuits are desire and temptation. In sharp contrast to the “rough and ready” look of The Flower Thief, Chumlum is quietly seductive for its brief 26-minute running time, aided considerably by Angus MacLise’s trance-like musical accompaniment. In this film, performance consists almost exclusively of a series of poses; inaction becomes action, and passivity enticement. It is enough to drift through the world of Chumlum with its protagonists; Rice has created a pansexual dream world in Chumlum that is both intoxicating and mesmerizing.

Ron Rice himself died of bronchial pneumonia in Acapulco, Mexico in 1964, not long after making Chumlum; his excessive lifestyle, and his insistence on putting the cost of film production before all other considerations (food, rent, and other more mundane expenses), seemingly ensured his early death from spectacular, performative self-neglect. In the late 1990s, looking back on the career of what he described as “the greatest director I ever worked with,” Mead described the genesis of The Flower Thief and how the film represented for him, and for Ron Rice, a departure from the conventional cinema as it was then being practiced, even at the margins of production:

The philosophies of the 50s ‘Beat’ writers came to cinematic fruition […] in the film Pull My Daisy [USA 1959] by Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie. I attended this film with Ron Rice, and we both picked up on how interesting and easy it was to respond to our surroundings in real life and even transfer to cinema. Though the ‘professionalism’ and cost of Pull My Daisy was even beyond our financial and mentally competent or inclined disposition. We thought we could make a ‘worse’ film, and it would cost a fraction of the well-lit and correlated Pull My Daisy. What I think we bought especially was the philosophy within the film of Allen, Gregory, and Peter, and their friends—that this was the new way to do things, including live. And in film Ron Rice’s basic advice to filmmakers was ‘Push the button.’ Unfortunately he carried ‘living’ to its ultimate at the early age of 28 … (Mead, p. 2)

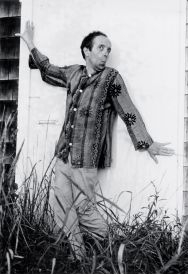

In Taylor Mead’s other performative films of the 1960s, Passion in a Seaside Slum and The Hobo and the Circus (both directed by Bob Chatterton; USA, 1961) and Lemon Hearts (directed by Vernon Zimmerman; USA 1960), Mead retains his childlike innocence in a world that continually seeks, without success, to corrupt him with the desire for conventional material rewards. Lemon Hearts, a 16mm 30-minute black and white film with an optical soundtrack, was financed by the actor Richard Kiley and produced in its entirety on an amazingly low budget of $50 (Sargeant, p. 88). Mead plays eleven different roles in the film, as he drifts aimlessly through the ruins of a series of soon-to-be-demolished Victorian houses, sometimes appearing in drag, sometimes in blue jeans and a sweatshirt.

The soundtrack is once again pirated from jazz records, interspersed with Mead’s own Beat poetry (“Oh God, oh God, oh God, my feet smell … I pissed on Jane Wyman’s picture”). In his lackadaisical avoidance of conventional plot and characterization in those films he appeared in, Taylor Mead, in concert with the filmmakers he worked with, created a cinema in which his performing body was the central focus of the camera’s gaze. Whenever he is off the screen in The Flower Thief or Lemon Hearts, the audience grows restless. Taylor Mead creates, with his gracefully languid nymph-like body and his blissfully blank expression, the perfect picture of absolute innocence in a hopelessly corrupt universe.

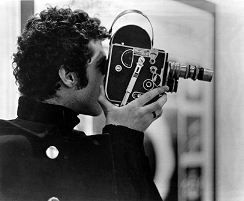

I knew Mead during the Warhol era in the late 1960s, and found him to be a fascinating, deeply innocent and vastly talented performer. Once, at Warhol’s 33 Union Square West Factory, I spontaneously began filming Mead with my Bolex absolutely without warning, and was stunned when he immediately improvised what he later termed “the Dance of the Ruptured Swan,” making up the choreography for the piece entirely on the spot. From a series of graceful pirouettes, Mead suddenly fell to the floor in mock agony, clutching his genitals, screaming “I’ve been castrated!,” while still attempting to carry on with his dance performance with a flurry of vigorous leg thrusts and extravagant arm gestures as he did so.

What amazed me even more was that as my spring-wound Bolex ended each 15-foot burst and needed rewinding, Mead would pause and wait for me to quickly rewind the camera. When we continued, Mead resumed the improvised sequence without a gap. I shot two 100’ reels of Mead in this fashion, without a word spoken between us, and when I had exhausted my supply of film, I simply gestured towards him and remarked “That was brilliant. Thank you.” With characteristic modesty, Mead, now in his non-performance persona, brushed off my praise with a wave of his hand, and I left the Factory with the very real sense that I’d just been in the presence of an authentic performing genius.

The other aspect that struck me as remarkable was that Mead had instinctively responded to the whir of my camera, reflexively kicking into performance mode without missing a beat. Further, I could make no claim for “directing” the footage I had just shot; Mead had improvised the whole thing from the start of filming. Nor did he inquire what I wanted, what I intended to do with the footage, or even who I was (we were relative strangers at the time). Simply put, Mead was the auteur of the sequence much more than I was; I was simply recording his performance on film.

In short, Taylor Mead was an ideal actor for a “hands off” director like Andy Warhol or from Ron Rice; given literally no direction, he transfixed the gaze of the camera with his consummate skill as a performer. But then again, this skill served Mead best in experimental cinema; although he has made a few frays into semi-commercial cinema, such as Jim Jarmusch’s portmanteau film Coffee and Cigarettes (USA 2004), when bound to a script, Mead seems tied down. A perennial free spirit, Mead is best left to his own devices.

In a similar vein, Mario Montez (born Rene Rivera in 1935 in Puerto Rico) was another distinctive performer, although his work was in a somewhat narrower vein, adopting the drag persona of a 1940s movie siren, patterned after the iconic Maria Montez, the “Queen of Technicolor” in such films as Robert Siodmak’s Cobra Woman (USA 1944). With her premature death at age 33 of a heart attack, Montez became the patron saint of gay “underground” actors and directors, and René Rivera, a New York City postal worker, adopted Montez’s name and extravagant attitude, bursting forth from the screen in a series of experimental epics, beginning with Jack Smith’s notorious Flaming Creatures (USA 1963), in which he was billed as Dolores Flores (“Zagria”). Flaming Creatures, a parody of the Arabian Nights costume pictures both Smith and Montez were so fond of, climaxed in a transvestite orgy coupled with an earthquake. The film was an instant success du scandale, and the object of numerous obscenity busts, but it became Smith’s signature work, and launched Montez into a sort of twilight stardom.

Subsequently, in Mario Banana No. 1 (USA 1964), Montez solidified his screen persona by seductively fellating a banana for four minutes in lavish, explosive color – just the sort of mise en scene that Maria Montez herself would have appreciated in form, if not content. Shot in style of Warhol’s “screen test” series – 100 ft. rolls of film run through a Bolex camera with an electric motor to capture all the action in one take – Mario Banana is at once a homage to 40s camp, and effectively Queers the entire costume drama genre with its shimmeringly aggressive shot composition. Framed in a tight, glamorous close-up, Montez regards the camera as a potential suitor, an object to be seduced, even as he eagerly consumes the banana for the spectator’s implied pleasure.

Montez then appeared in Warhol’s Screen Test Number 2 (USA 1965), as well as Warhol’s Harlot (USA 1965), loosely based on the cult of Jean Harlow, and Hedy (The Shoplifter) (USA 1965), a spoof of Hedy Lamaar’s Hollywood career. Her penultimate appearance in a Warhol film was a brief cameo in Chelsea Girls (USA 1966), in which Warhol pushed her in front of the camera to sing “They Say Falling In Love is Wonderful,” while two men engage in a sexual liaison on a sloppily made bed. Montez’s performance has a double edged verisimilitude; one is conscious of the drag aspect of his on-screen persona, but at the same time, Montez embraces his alter ego with such fervent devotion that the masquerade becomes almost transparent; he is what he presents himself to be, a transgendered figure of androgynous desire, upon whom the audience can project either a male or female gender identity.

As Montez says forthrightly, “I learned my acting basically from watching old movies,” and so his performances form a link not only between masculine and feminine performance styles, but also classical Hollywood and the New American cinema of the 1960s, which discarded many of the “rules of the game” by which the cinema had previously operated. Not that he made much money at it; “With Warhol, everyone was forced to sign releases before you did anything. We were all naïve and we signed away […] I was working [in] the daytime as a clerical worker and I had to squeeze in time to do things for Warhol, [as well as theatrical performance artist] Charles Ludlam. I don’t know how I did it” (Martorell). Eventually, Montez decided that New York was too inhospitable a climate, and in the late 1970s, moved to Florida, more or less abandoning his performing career, although he is from time to time lured out of retirement at benefit screenings for Warhol’s films, or those of Jack Smith.

Gerard Malanga, once Andy Warhol’s right-hand man, and now a fulltime photographer and archivist, created a series of deeply romantic films in which his own persona of “the young poet” was foregrounded in each frame. In contrast to the gaze of Warhol’s detached, somnolent Auricon camera, loaded with 35 minutes (1200 ft.) of 16mm film at a clip to record the happenings staged by Warhol’s Factory regulars, Malanga’s films, shot almost entirely with a hand-held Bolex, present a world in which all is celebration, beauty, and sacrifice of the self for art. While such early Warhol films as Camp (USA 1965), a shoddily improvised “variety show” featuring Paul Swan, Baby Jane Holzer, Jack Smith, Mario Montez, and Tosh Carillo also present the human body as the sole point of interest to the gaze of the camera, Warhol’s informing strategy in such films as Horse (USA 1965), The Life of Juanita Castro (USA 1965), Vinyl (USA, 1965), Poor Little Rich Girl(USA 1965), and his magnum opus The Chelsea Girls (USA 1966) is to confront the performer (and spectator) with the documented image of the performing body.

Malanga’s hand-held, restlessly moving camera interprets the actions he records; with In Search of the Miraculous (USA/Italy 1967), Malanga creates an emotional, vivid poem of adoration for his then-fiancée, Benedetta Barzini. Other early Malanga films also put the performer center stage within the filmmaker’s lens, which once again extends rather than contains the performances it records. Mary for Mary (USA 1966) is a portrait of the actor Mary Woronov; Donovan Meets Gerard (USA 1966) documents a performative meeting between Malanga and the folk singer, Donovan, at Warhol’s studio, which is obviously staged for the recording camera. One of Malanga’s most ambitious works, the 60-minute, split screen, two-projector, stereo sound Pre-Raphaelite Dream (USA 1968), documents the filmmaker’s friends and extended family in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as they perform their lives for the camera. In The Recording Zone Operator (Italy 1968), shot on location in Rome in 35mm Techniscope/Technicolor, Malanga worked with Tony Kinna, Anita Pallenberg, and members of the Living Theatre to improvise a 40-minute performance piece in which a group of gay “angels” accost passersby in a local park, leading to an orgy in a nearby apartment.

The almost forgotten Kip Coburn created a series of sensuous personal films, working entirely in standard 8mm reversal color, with sound-on-tape accompaniment. Such films as Cocain [sic], Flesh, Hitchhiker, Johns Doll [sic], Trips, Stoned, and Colors (all USA; all undated) document an internal odyssey in which the filmmaker is at one with the world he creates, presenting himself as the ritualized performer in a drama of the artist’s quest for life beyond the boundaries of normative experience. Similarly, Storm de Hirsch’s Divinations (USA 1964), Peyote Queen (USA 1965), and Shaman: A Tapestry for Sorcerers (USA 1966) extend the filmmaker’s body into the performance space of the film frame, as de Hirsch photographs herself, nude, through a variety of prismatic lenses and diffusion filters, presenting her body as the site of ritualistic display to her audience.

Ed Emshwiller’s Dance Chromatic (USA 1959), Lifelines (USA 1960), and Thanatopsis (USA 1962) center on the body in motion, particularly in dance as a location of celebration of the human instinct for physical pleasure and self-expression. Arnold Gassan’s Marsyas (USA 1963) follows the plight of an African-American who seeks to escape, metaphorically, the suffocating domination of the white world around him. Fleeing from the city into the woods, he is symbolically castrated, and then, in the final images of the film, confronts himself as a negative-imaged ghost in his bathroom mirror. Disturbing and powerful, Marsyas offers us a performative vision of the loss of human identity through the twin exigencies of social alienation and racial marginalization, and focuses on only one character, Don Crawford (as Marsyas), throughout its 12-minute running time.

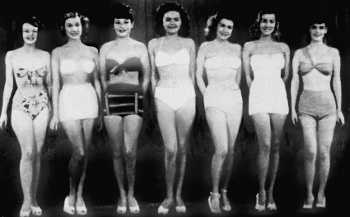

Gunvor Nelson, working with Dorothy Wiley, created the groundbreaking film Schmeerguntz (USA 1966), which deals almost exclusively with the traditionally non-documented physical aspects of childbirth and child rearing: nausea and vomiting, cleaning dirty diapers, morning sickness, and the general chores that one must accomplish when one gives birth to a child. Intercut with clips from 1930s beauty pageant films and other images of the “idealized” feminine corpus, as well as clips from the Jack La Lanne exercise program (“Merrily we exercise!” Jack sings, as Gunvor Nelson and Dorothy Wiley, in their ninth month of pregnancy, struggle simply to navigate the length of their cramped apartment), Schmeerguntz is a 15-minute expression of anger, disgust, and protest against a society which artificially sanitizes and erases images of the reproductive body from the mainstream media.

In a much more celebratory vein, the late Barbara Rubin’s Christmas On Earth (USA 1963), astonishingly created when the filmmaker was only 18, is a 30-minute 16mm double-projection film, in which two separate reels of images of the human body engaged in sexual intercourse, straight and gay, are superimposed to create a landscape of desire and corporeal performance which remains one of the most audacious cultural statements of the 1960s. Rubin photographed the images for the film in a free-form, documentary manner, then cut the developed reels of film into short strips, threw them into a basket, and drew the individual shots out one by one, splicing them together in random order.

As Daniel Belasco notes of the making of the film:

In June 1963, [Rubin] corralled five friends into the Ludlow Street crash pad rented by musicians John Cale and Tony Conrad and instigated a night of playful debauchery. “Barbara held us hostage for 24 hours, from early evening to the next day. It was very Cocteau-ish. We were locked in and hermeticized in this apartment, it was a very freewheeling situation,” recalled Gerard Malanga, one of the performers in the film [in a telephone interview with Belasco].

This free-associational approach to the shooting and editing of Christmas On Earth extended to the film’s presentation, as well. After extended consideration, Rubin cut the finished film into two separate reels, screening the images on two projectors simultaneously to create another layering of imagery within the work. While requesting that one projector’s image fill the entire screen, and the second projector’s image be “approximately 1/3 smaller, [filling] only the middle of the screen,” Rubin was very much interested in enlisting the projectionist of her film as a co-creator of the work, as evidenced by these remarks to the projectionist, found on a sheet of paper enclosed in the film can:

It doesn’t matter which reel is on which projector. During the screening, the projectionist is asked to play with color changes by holding colored filters in front of the lens of one or the other projector, or both. Moreover, the film has neither head nor tail – it can be projected either way. (FMC Catalogue No. 4, 129)

Rubin’s vision of the human body as a performative site of pleasure, desire, mystery, and ritual role play is certainly one of the most direct to come out of the 1960s American Experimental Cinema, and one of the most unashamed. By holding up the human body (male and female) to the careful scrutiny of the camera lens, Barbara Rubin in a single film managed to reclaim the sexualized body from the zone of pornographic representation it inhabits in the Dominant Cinema, as a location of fear and prurient desire. Instead, the Edenic images Rubin offers the viewer in Christmas On Earth remind us of our own genesis, our life and breath, and our concomitant mortality.

Ben Van Meter, a West Coast filmmaker most active in the 1960s, created a gorgeous series of films that celebrate the human body in such works as The Poon-Tang Trilogy (USA 1964), Colorfilm (USA 1964-65), Olds-Mo-Bile (USA 1965), and his epic Acid Mantra: Re-Birth of a Nation (USA 1966-68), a 47-minute color and black and white work of such propulsive energy and intensity that viewing it is almost an exhausting experience. Starting with footage of various rock bands in concert, including the Velvet Underground and the Grateful Dead, the film superimposes as many as ten different layers of images simultaneously to engulf the viewer in a cornucopia of sight and sound, all leading up to a climactic orgy during a summer picnic at a party in the Bay Area countryside.

Men, women, and children are seen frolicking about nude, unashamed before Van Meter’s camera: swimming, playing Frisbee, lounging on the grass in the late afternoon sunlight. As the film enters its final third, the men and women participate in a celebratory group sex experience, which we barely glimpse through a haze of filters, quasi fabrics, and competing imagistic material. As the couples engage in ecstatic sexual performative role-play, Van Meter drips blobs of colored paint directly on the film, as if to suggest the intensity of the energy that is being released by this performance. As the film ends, we see family units once again engaged in relaxed outdoor activities still in the nude, playing various sports, relaxing, or walking in the tall grass with their children.

Carolee Schneemann created the beautiful film Fuses (USA 1964-1968), a 22-minute meditation on the act of lovemaking, which Schneemann photographed with her partner during the act of intercourse. Unlike the stratified images of sexual activity removed from any human context, Carolee Schneemann, throughout the film, allows her camera to film the family cat disinterestedly watching them or window curtains blowing in the afternoon breeze. Schneemann also created a number of performance pieces during the 1960s and 70s, which involved the use of her body as a site of performative ritualistic display; sometimes these events were documented, but often they remained merely as memories in the minds of those in the audience. José Rodriguez-Soltero’s Jerovi (USA 1965) and Naomi Levine’s Jaremelu (USA 1964) celebrated the act of masturbation as a rite of sexual performance and self-actualization in a way in which even censors of the period found unsettling. Jerovi and Jaremelu were both denied admission to the 1965 Ann Arbor Film Festival on the grounds that they were “pornographic,” as the late Gregory Markopolous reported in an essay on the festival.

… I learned that certain films had not been admitted to the festival because Mr. Manupelli’s selection committee thought them unworthy of inclusion. Among these were Naomi Levine’s lovely Jaremelu and Jose Soltero’s Jerovi, another film on masturbation like [Nathanael Dorsky’s] Ingreen [USA, 1964] but more direct. A part of the selection committee ran Jerovi and they were visibly shaken. One young woman immediately proclaimed it “pornographic.” “What’s pornographic about it?” I asked. No reply … (FMC Catalogue No. 4, 128)

Warren Sonbert began his filmmaking career with Amphetamine (USA 1966), a student film Sonbert shot in February of that year featuring his friends and roommates shooting up amphetamine on camera, then engaging in passionate gay sexual displays of performative lovemaking. The film was stunning both in its apparent artlessness as well as its unashamed embrace of both the drug culture and the performative act of homosexual lovemaking, performed directly in front of Sonbert’s camera. Shot in 16mm black and white and scored to the beat of 60s rock and roll, Amphetamine was hailed as one of the clearest and most direct films of the 1960s, receiving an ecstatic review from critic James Stoller

… Amphetamine is especially symptomatic as in its intimation that the filmmaker has not performed enough work for this to be art. But I would suggest that the work has indeed been done, although principally in an unaccustomed direction: the direction of freeing the imagination first so that a statement could be made for which, in its transparency and unpretentiousness, there was no comfortable precedent. The result is beautiful and pure: behind the bald surface we feel, first, that many inessentials have been cleared away, and then, that the need for them has been cleared away. (FMC Catalogue No. 4, 141)

One of the most compelling images in the film, indeed, is the result of an accident. As Sonbert told me in 1969, he was shooting another film about the denizens of 42nd Street in Manhattan, then a notorious zone of drugs and debauchery, when the film in his camera lost its loop, resulting in a (supposedly) completely unusable image. When the footage came back from the lab, he was advised to simply throw the material away. But Sonbert saw the value in embracing this mistake, much as Marcel Duchamp would have done, and cut sections of the light, fluttering material into Amphetamine to create what Stoller referred to an “exquisite blur,” right before a “shock cut” to two young men locked in a passionate embrace, while Sonbert’s camera swoops around them in an ecstatic dance of communal abandon.

Sonbert went on to a long and riveting career as a filmmaker; while his later works are much more formalist, starting with the structuralist film Carriage Trade (USA 1971), his early films, such as Where Did Our Love Go? (USA, 1966), Hall of Mirrors (USA 1966) and The Bad and the Beautiful (USA 1967) belong to the classical period of American experimental cinema, and document the lives and loves of his large circle of friends and colleagues, often scored to rock and roll soundtracks, to create an indelible, ineffably romantic portrait of life in New York City during what was arguably its greatest period as an artistic breeding ground for all the arts, not just film.

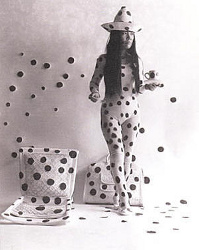

In similar fashion, Jud Yalkut’s Kusama’s Self Obliteration (USA 1967) offers us a vision of the Japanese performance artist, Yayoi Kusama, engaged in a “self-obliteration” ritual in which she paints dots of color on leaves, animals, various other objects, and finally on a group of people ecstatically copulating in one of Kusama’s endlessly mirrored “Infinity Chambers,” who carry on making love, seemingly oblivious to Kusama’s painterly brushstrokes being applied to their naked skin. By linking nature in the form of trees, flowers, grass, and animals to the human experience of performative re/production, Kusama demonstrates that the physical fact of “individuality” is mediated by the performative act of “self-obliteration,” in which individuality is subsumed into the larger fabric of shared existence. Kusama, whose work as a performance artist, painter and sculptor is now undergoing a major renaissance, was one of the first artists in the 1960s to incorporate performativity into her work, which was presented with or without the apparatus of documentation. It is only because Jud Yalkut was present with his camera that we have the record of Kusama’s performance work in her Self Obliteration piece; many of her performance works were documented only with stills, or not at all.

Sara Kathryn Arledge, a pioneering feminist filmmaker who began making 16mm color films in 1941, produced a series of meditations on human sexuality and ritual body display in such films as Introspection (USA 1941-1946), What Is A Man? (USA 1958), Tender Images (USA 1978) and others, which celebrated the union between masculine and feminine with a directness of address that still strikes the viewer as being fresh and original. Arledge was a pioneer in this area, making films that were uncompromising in their graphic specificity for the era, depicting sexuality as a performative human act rather than inhabiting the pornographic zone of the forbidden.

As Judith Butler notes, with filmic pornography, “‘construction’ is not simply the doing of the act … but the depiction of that doing” (p. 221), depicting the act of sexual intercourse in a manner which can be construed as degrading and/or dehumanizing. Arledge’s work directly tackles the issues of filmic sexual performativity and transcends the mere documentation of human sexuality through the mediation of her humanist gaze. In similar fashion, husband and wife Marie Menken and Willard Maas collaborated on the precedent shattering film Geography of the Body (USA 1943), which re-viewed the human body in extreme close-up with the aid of magnifying lenses and specially designed filters.

All of these films retain their power to impress audiences today, if only because of their inherent innocence and lack of shame, a visual and sexual freedom that arose out of an era of pre-viral consciousness. We will never see the like of the performative “body work” films of the 1960s again. It would be impossible and inauthentic to attempt to recreate them. These performative films of human sexuality and ritualized body display were a response to the repressive atmosphere of the 1950s and a breaking down of then-established rules of gender, sex roles, and social taboos. In the films discussed in this essay, the viewer can see the human body as the site of ritualized displays within a social context of imagistic and sexual self-actualization, a revolutionary act that altered the course of the cinema both in its explicitness and honesty. The legacy that these films bequeath to us today is a terrible vision of the beauty of the human body as a performative locus of both fear and desire, the domain of the spirit made visible and tangible.

In all experimental cinema, “performance” is a value that is very much in flux, both during the production and viewing of the film. Straight viewers get one set of responses; gay viewers another; lesbian and transgendered spectators yet another series of insights; and bisexual viewers receive still another series of takeaway impressions. Gender performance is one of the central concerns of classic experimental cinema, but added to that, such artists as Warhol (and his scenarist, the late Ronald Tavel) purposefully set out to investigate the limits of filmic narrative, and question what passes for a “performance” in a film. In conventional, mainstream cinema, foreign or domestic, the role of the actor is clearly defined, as a person who can learn lines, hit marks, and seemingly “become” the character they are playing, shedding their own personality as part of the performative process.

Experimental films largely rely on their protagonists to bring themselves, rather than a set of inherently artificial and mimetic skills, to the set: thus, in a very real sense, the individuality and intensely personal approach one sees in the films discussed in this article represents arguably a more genuine connection to the “real” than any scripted performance. There is a genuine element of risk and spontaneity in these films that is often absent from mainstream cinema, with its all-too-often predictable story arcs, twist endings, and recycled plot lines.

Experimental cinema, in contrast, puts the heart on trial, as it exposes the fears and ambitions of its protagonists, performing for the love of the art, rather than any conventional critical acclaim. In the end, then, experimental films, almost by definition, interrogate the very process of traditional screen acting, and find it innately superficial, and often lacking in real human resonance. Not everyone is willing to open himself or herself up to the scrutiny of such a naked gaze; those who are gesture towards a re-evaluation of theatrical and cinematic standards of performance, and in the process, bring us closer to ourselves.

Works Cited and Consulted

Arledge, Sara Kathryn. “The Experimental Film: A New Art in Transition.” Arizona Quarterly (Summer 1947): 101-112.

_____________. “Brief Statements.” Canyon CinemaNews 1980/6-1981/1: 5.

Banes, Sally. Greenwich Village 1963: Avant-Garde Performance and the Effervescent Body. Durham, NC: Duke University P, 1993.

Battcock, Gregory. The New American Cinema. New York: Dutton, 1967.

Belasco, Daniel. “Barbara Rubin: The Vanished Prodigy,” Art Signal 5, http://magazine.art-signal.com/en/barbara-rubin-the-vanished-prodigy/. Accessed October 25, 2010.

Berg, Gretchen. “Nothing to Lose: An Interview with Andy Warhol.” Cahiers du Cinema in English 10 (May 1967): 38-42.

Bourdon, David. Warhol. New York: Abrams, 1989.

Burckhardt, Rudy. “Warren Sonbert.” Film Culture 70/71 (1983): 176.

Butler, Judith. “Burning Acts – Injurious Speech,” Performativity and Performance. Parker, Andrew and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, eds. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Canyon Cinema. Canyon Cinema Catalogue No. 7. San Francisco: Canyon Cinema Collective, 1992.

Curtis, David. Experimental Cinema: A Fifty-Year Evolution. New York: Delta, 1971.

Dixon, Wheeler Winston. “The Early Films of Andy Warhol.” Classic Images 214 (April 1993): 38-40.

_____________. The Exploding Eye: A Re-visionary History of 1960s American Experimental Cinema. Albany: State University of New York P, 1997.

Filmmakers’ Cooperative. Filmmakers’ Cooperative Catalogue No. 4. New York: New American Cinema Group, 1967.

Hammer, Barbara. “Sara Kathryn Arledge.” Canyon CinemaNews 1980/6-1981/1: 3-4.

Indiana, Gary. “I’ll Be Your Mirror.” Spring Art Supplement 3.1, The Village Voice, May 5, 1987: centerfold section, 2-3.

MacDonald, Scott. A Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers. Berkeley: University of California P, 1988.

Malanga, Gerard. “A Letter to Warren Sonbert.” Film Culture 46 (Autumn 1967): 20-21.

_____________. “The Secret Diaries” (excerpt). Cold Spring 9 (January 1976): 4-10.

_____________. “Working with Warhol.” Art New England (September 1988): 6-8.

Martorell, Carlos Rodríguez. “Columbia U. Holds Tribute to Mario Montez, a Boricua Drag Performer From Warhol’s Era,” The New York Daily News.

March 31, 2010, http://www.nydailynews.com/latino/2010/03/31/2010-03-31_columbia_u_holds_tribute_for_mario_montez_a_boricua_drag_performer_from_warhols_.html. October 14, 2010.

McCreadie, Marsha. Women on Film: The Critical Eye. New York: Praeger, 1983.

Mead, Taylor. “Notes on The Flower Thief,” Anthology Film Archives Program Notes (January-February, 1998): 2-5.

Mekas, Jonas. Movie Journal: The Rise of the New American Cinema. New York: Collier, 1972.

Moore-Gilbert, Bart, and John Seed, eds. Cultural Revolutions: The Challenge of the Arts in the 1960s. London: Routledge, 1992.

Myers, Louis Budd. “Marie Menken Herself.” Film Culture 45 (Summer 1967): 37-39.

Rabinovitz, Lauren. Points of Resistance: Women, Power, and Politics in the New York Avant-Garde Cinema, 1943-1971. Urbana: University of Illinois P, 1991.

Rice, Ron. “Note from Ron Rice to Jonas Mekas.” Film Culture 70/71 (1983): 100-111.

Sargeant, Jack. The Naked Lens. London: Creation, 1997.

Schimmel, Paul. Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949-1979. Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1998.

Shaviro, Steven. The Cinematic Body. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota P, 1993.

Stark, Scott. The Flicker Pages. http://www.sirius.com/~sstark/welcome.html. December 13, 2009.

Sonbert, Warren. Unpublished interview with the author, Spring, 1969.

Taubin, Amy. “Warren Sonbert, 1947-1995.” The Village Voice, June 20, 1995: 48.

Tyler, Parker. Underground Film: A Critical History. New York: Grove, 1969.

Youngblood, Gene. Expanded Cinema. New York: Dutton, 1970.

“Zagria.” “Whatever Happened to Mario Montez?” A Gender Variance Who’s Who, July 25, 2008. http://zagria.blogspot.com/2008/07/whatever-happened-to-mario-montez.html. December 13, 2009.

Portions of this essay originally appeared as “Performativity in 1960s American Experimental Cinema: The Body as Site of Ritual and Display,” in Film Criticism 23.1. Reprinted by kind permission of Lloyd Michaels, editor.

Created on: Sunday, 7 November 2010