Abstract

Approaching the millennium, and in its immediate wake, a strong sense of historical lateness emerged, a very particular fin de siècle. In film history, this was immediately preceded by the milestone of 1995, with its retrospective gaze across the first century of cinema, complemented by a gaze into the future. And the rise of digital technology ensured that the circulation of future images would take different paths. The present article explores the confluence of these currents in cinema history and national history. The four main case studies are The Hours; The Thin Red Line; Run Lola Run, and Mulholland Drive.

…..

Introduction

The films treated here appear at a very particular point in history, the millennium, spanning a couple of years each side of the year 2000. These films – The Hours (USA/UK 2002), The Thin Red Line (USA 1998), Run Lola Run (Germany 1998) and Mulholland Drive (France/USA 2001) are the main points of reference – were made at various stages of their directors’ careers and life-spans. As a group, the films considered here in no sense resuscitate for postmodern times the anachronistic notion of a shared artistic core, a ‘movement’. But they, as well as their contemporary audiences, were conscious of the convergence of three historical markers, 1) the first centenary of cinema, celebrated globally in the year 1995; 2) a sense of the end of the century being nigh; and 3) a further sense of this being a fin de siècle [1] unlike others, namely the threshold to a new millennium. In relation to periodization, that kind of Janus-faced[2] historical vantage point is comparable to terms like ‘neoclassicism’ (with reference, say, to Stravinsky), the conscious citation of an older, but not immediately preceding direction, while celebrating the new ‘take’ on it. There is little, if any, sense in these films of an apocalypse, such as permeated German Modernism’s take on lateness, though we might be tempted to look for such elements with our knowledge of their proximity to 9/11. An extensive body of such millennial films exists, more in the domain of disaster movies. The latter express what Kirsten Moana Thompson calls ‘apocalyptic dread’, as a reflection of ‘social anxieties, fears, and ambivalence about global catastrophe’.[3] In the films discussed here, on the other hand, there is little trace of such dread, and little, too, of the Eurocentrism that attaches to the usual suspects in late style discussions (Beethoven and Shakespeare in particular). Such tunnel vision overlooks a director like Kurosawa, who proves to be fertile territory well before his own dreams/Dreams (USA/Japan 1990) of old age. On the Madman DVD commentary to his film The Bad Sleep Well (Japan 1960), to some extent Kurosawa’s Hamlet adaptation, Ross Gibson draws attention to the echoes of film noir interacting with echoes of Shakespearean themes, and both with a still older Japanese courtly society.[4]

The editor of The Musical Quarterly referred recently to ‘the now fashionable concern for “lateness” as an interpretative category within biography and history’.[5] Different issues arise when speaking of movements or periods within and even across the arts, Late Romanticism, etc. If ever valid, the Romantic notion of late style, of a corpus of late Beethoven music or late Shakespeare plays that stands out from their earlier works, can not be applied to film.[6] Within film history, however, lateness can be meaningfully applied to stages like the transition from the silent era to the talkies (or its failure, the glorious anachronism of Norma Desmond), or else the demise of the Hollywood studio system, the latter clearly present for instance in John Huston’s The Misfits(USA 1961)[7] and Godard’s Contempt (France/Italy 1963). Film was an artform not in existence when the notion of ‘late style’ emerged. THE new art form of the 20th century has set others in motion in a way not contemplated when the notion of ‘late style’ first peaked.

The analyses that follow do not pursue the twilight years’ output of auteurs, but commonalities of style, and narrative patterning, at a historical turning point marked by lateness. The focus on this aspect necessarily restricts more general interpretation of the foregrounded films. Lateness becomes a particular form of intertextuality, defined by Riffaterre as “the reader’s perception of the relations between a text and all the other texts that have preceded it or followed it”.[8] And the millennial group considered here then becomes a particular example of lateness, which prominently exhibits intertextuality. The historical window of the main examples is narrow – a mere half decade in history, and in contemporary film history. But potentially the threshold of digital technology – significant here in Run Lola Run and Mulholland Drive – can already be ranked in importance alongside the coming of sound, or the decline of the studio system. And viewed that way, the avant-garde quality that had held so long for film as art is thrown into question. Beyond the waxing and waning of movements, genres and industry factors, the very nature of the image, at the end of a century dominated by images, comes to be at stake.

This article pursues epochal ‘lateness’, not individual late style.[9] These directors view lateness not as an either/or between return or advance, but as combining both. One of the main indicators of such lateness is intertextuality, but of a particular brand, not cinephilia as such. Intertextuality in this context foregrounds historical linkages and faultlines, locates texts within (a well advanced stage of) problematized genres, and operates in an almost archaeological sense of layering tectonic plates. It characterizes works steeped in late history, which can be cinema history and/or national history. Ahead of the main films considered, these two categories will be established via briefer analysis of other millennial films.

Cinema history/National history

Todd Haynes’ Far from Heaven (USA 2002) addresses cinema history (with its direct references to Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (USA 1957) and Fassbinder’s Fear Eats the Soul (Germany 1974)). It also gives a melancholy gloss on US national history at the level of bourgeois domesticity, as the small-town family, the heart of so much melodrama, implodes at the end. The autumnal tones are not exhausted by this film’s atmosphere (Cathy’s soft voice and frequently glazed expression, departures from which are all the more spectacular) and mise-en-scène (the Fall colours; costuming). They extend too to the historical positioning of the melodrama genre, and to the narrative discourses of sexual politics – gay rights, and the feminist movement, then, and now, and in between then and now. In cinema history Fear Eats the Soul occupies just such an ‘in between’ (surrounded by the two US examples). Its strong presence takes Haynes’ film far beyond the scope of a kind of Sirk remake; it is at most a Sirk remake of the second order, filtered via Fassbinder’s engagement with Sirk. Fassbinder’s film is most notably echoed in the intimacy and soulfulness of Cathy and Raymond, the Afro-American catalyst, dancing in a no whites club. This contrasts with the ritual, stilted dance of Cathy and her husband Frank on New Year’s Eve (another marker of lateness, and liminal temporality). Fassbinder’s blend of social commentary with the domestic themes and spaces of melodrama is more direct than Sirk’s, and it is arguably that blend that Haynes is most strenuously trying to recuperate. Frank’s façade of overtime at the office is easily sustained, while in fact he’s cruising male-only beats. This is a striking variation of classic 19th century melodrama, where the male would, maybe would be expected to, visit prostitutes, but only ever females. The already complex engagement with lateness gains from our own timeframe, just eight years on from the film’s premiere, with the significant extra dimension of Barack Obama as President of the country of Hartford, Connecticut. Not only in the film’s pre-integration time setting, but probably still to Haynes, that was beyond imagining. But the early 21st century context of the film’s conception also implies the lateness of 19th century residues in melodrama, perhaps the genre most in danger of being viewed universally rather than historically.

Sokurov’s Russian Ark (Russia/Germany 2002) is a historically late take on national history. It embraces a conscious rearguard action, with its ‘insistence on a legendary Petersburg’ serving as ‘an ill-disguised rejection of the Soviet regime’.[10] Beyond the virtual confinement of its historical arch to pre-WWI years, the film retracts Eisenstein montage as a marker of film history, by providing its polar opposite. It has the length of a feature-film, yet is shot in a single take. Far beyond his aesthetic stance, that of a cinematographic flâneur, Sokurov returns us to pre-Soviet history as well as cultural history. The film evokes the past that the city could have had, in that one sense akin to the historical subjunctive mood of Goodbye Lenin (Germany 2003).[11] And historians’ growing interest in counterfactuals shows a discipline seeking a stylistic equivalent to virtual reality, and an ontology which extracts from nostalgia as lateness the filter of desire, not the pretence of mimesis. Russian Ark marks a parallel to Said’s claims for Richard Strauss’ relationship to music of the 18th century[12] ; retro almost as artistic and historical credo, rather than as one stylistic choice among others. Sokurov’s undoubted achievement is to signal film’s capacity to suggest synchronicity independently of editing as technique, to genuinely rove across the chronological borders of history (including those bounding ‘lateness’).

The Hours

The converse typifies Stephen Daldry’s The Hours. The film’s title foreshadows a cyclical lateness. But the film is also about what lies beyond lateness.[13] David Hare’s screenplay closely follows Michael Cunningham’s 1998 novel of the same name. Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) saturates, but far from eclipses, Cunningham’s novel. The Hours was the original working title of Woolf’s novel; Woolf herself is one of Cunningham’s characters. In both novel and film Woolf’s life is paralleled with Laura Brown (suburban domesticity in LA, 1951), and Clarissa Vaughan (a New York publisher, 2001). Their connectedness across generations and geography is established early in the film by match-cuts, with the editing of match shots sutured still further by the ongoing flow of Philip Glass’ music.

Daldry’s film yields both a retrospective view of the historic Virginia Woolf and her legacy, as well as a patterning of narratives across literary, visual and musical forms. Beyond adaptation issues, the medium of film could be seen as one ‘late style’ of literary narrative, despite the interest of Woolf and many of her contemporaries in film. But the relationship between literature and film changed radically between the age of Virginia Woolf and that of the contemporary story in The Hours. Referring to the 1920s, Mikhail Iampolski writes:

The cinema promised the overcoming, within language, of the literary tradition. A literary text oriented towards the poetics of film was thus obliged to enter into a negative relation with the intertext of the broader literary arena. The cinema drew such a text into a kind of negative intertextuality, one that denied the wider context of culture.[14]

The reverse of such ‘denial’ holds for Daldry’s film, based on Cunningham’s novel, itself a stage of the reception history of Virginia Woolf’s novel. The Virginia Woolf sequences of the film negotiate territory which, unlike literary adaptation, is not obviously congenial to the moving image – the very processes of creative writing itself. The gestation process behind the written word is more akin to prose (unless exposed to the vagaries of voice over in film), and more at home in prose. A biopic subgenre of prominent writers and their creative processes (as opposed, say, to prominent composers) is likely to be sparse, even with a director with rich soundtracks such as Jane Campion (Sweetie [Australia 1989], The Piano [Australia/NZ/France]). When engaging with the biography of a writer (Janet Frame, in An Angel at My Table [New Zealand 1990], or Keats in Bright Star [UK/Australia/France 2009]), she reduces the narrative presence of creative writing in favour of other details, less related to the inner life, which are hence more readily realizable in a medium with images as concrete as film’s. But in her depictions, and all the more so with Daldry, writing emerges triumphantly as a legitimate cinema subject, not simply a topic for dialogue. If a ‘negative intertextuality’ prevailed at an earlier stage of cinema history, one of overweening assertiveness, then by the millennium this imbalance has been redressed. Viewed thus, The Hours embodies lateness in its bedrock of intertextuality – the centrality of Woolf’s novel – but also in the positive intertextuality it affirms between film and literature.

Cunningham’s novel combines a homage to Woolf’s with a reworking of it, at two generational/historical removes. The triptych of women represents the creation, the reception (Laura Brown reads Mrs Dalloway in bed) and an enactment of Woolf’s novel. Virginia Woolf conceived Mrs Dalloway but remained without biological children; Clarissa in New York has a child through artificial insemination. These mirror images show that, both in career and motherhood, the advances for which the historical Virginia Woolf strove have led to unexpected outcomes at the end of her century. As well as being late flowerings of the core text, both film and novel become ruminations on late history (e.g. the known circumstances of the death of Virginia Woolf; millennial anxieties about AIDS, the cause of Richard’s suicide). The historical Virginia Woolf and contemporaries like Faulkner and Joyce strove to privilege individual consciousness in the wake of the 19th century omniscient narrator. At the end of the millennium, Glass’ score stands in for the anachronism of an omniscient narrative viewpoint. The panoramic, millennial perspective of Cunningham’s reader and Daldry’s viewer is one that contrasts strikingly with a single divergence from Glass’ score. Affording a brief afterglow of Romantic self-transcendence, one of Richard Strauss’ Four Last Songs is counterpointed against Glass’ music, presenting a Janus-face on contemplating death, and on recalling the summer shared by a youthful Clarissa and Richard. The pivotal role of this music in the narrative of Daldry’s film creates an afterlife for Strauss’ own late style. All three women share a proximity to death, though with increasing distance; with significant refraction, the spirit of Virginia Woolf lives on.

The Thin Red Line

A different layering effect characterizes Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line. Loosely based on the James Jones novel of 1962, which had been filmed in 1964 by Andrew Marton, Malick’s version has a less direct relationship to its primary text than Daldry’s film to its point of departure. The Thin Red Line represents an extreme example of the war movie genre, and its historical inflections, as well as being a philosophical reflection on war. In relation to Malick’s art, Simon Critchley pleads for understanding film as a form of philosophizing, which would make film a latecomer style, but also a rejuvenated style within the discipline of philosophy[15] Remote from national self-aggrandizement, the frequently disembodied voice-overs in this film pose questions like: ‘This great evil, where does it come from?’ Not least, this is a gloss on the Hollywood war movie’s assumption of fighting for an unquestionably right cause, in WWII, and also on the intervening wave of progressively disillusioned Vietnam depictions. Already strikingly different from Spielberg’s Oscar-winning Saving Private Ryan (USA 1998), released the same year, Malick’s film is different again from another example of lateness within the genre, Clint Eastwood’s companion pieces Letters from Iwo Jima (USA 2006) and Flags of Our Fathers (USA 2006).[16] Eastwood’s films attempt to balance the ledger of depictions of the enemy, with depictions of the one battle from opposing perspectives.[17] Market forces, film (self-) censorship and cultural memory combine to make this enterprise probably only conceivable at a significant historical gap from the events depicted.[18] Malick’s film embodies a ‘transnational aesthetic’[19] , a term that Randall Halle applies to lateness in the war movie genre in a European context (historically of course a very different context).

With Malick, the real battle of Guadalcanal recedes from the foreground. Despite being a military victory, i.e. unlike Vietnam, it does not need a Rambo-type figure to rewrite history. Guadalcanal is taken as a given, a historical starting point for examining far broader cosmic concerns. Backlit forest canopies here are reminiscent of establishing shots in Platoon (UK/USA 1986). But with Malick they are just part of the parallel, yet superimposed realm of nature, which makes this film so distinctive when viewed as a genre-film. When Captain Staros shelters his men, Lieutenant-Colonel Tall tries to harden him by claiming that Nature is cruel, a Darwinian view of life that is to be transferred to warfare. But the cinematography and editing of the film have consistently told us otherwise.[20] Private Witt ultimately gives his life so that others might live. His progressively Christ-like depiction echoes the death throes of the William Dafoe-figure in Platoon or the Robert de Niro-figure prostrate beneath a basketball frame before the battle sequences of The Deer Hunter (UK/USA 1978), but without their overt iconography. In Platoon, this image completed the Stations of the Cross of post-Vietnam US. Malick’s film, further distanced from Vietnam, encompasses this body of films, but far exceeds their narrative ambitions. This is lateness, as Gordon McMullan suggests of late style, as ‘a form of commemoration’.[21] But in a pivotal scene after the Americans have captured a position held by the Japanese, rhetorical questions in voice-over are meditative, anything but triumphal. An American soldier and a Japanese captive hold a dual-language ‘dialogue’ seemingly past each other.[22] The scene is unified by roughly three minutes of music not belonging to Hans Zimmer’s original score. It is a composition by Charles Ives, like Malick something of an exceptional genius in his homeland. So over two languages not in dialogue, we hear the language of music, a piece whose programmatic title poses a philosophical question, ‘The Unanswered Question’. Referring to the culturally loaded Venice in Britten’s opera Death in Venice, Said wrote of a ‘recapitulation and return for a long artistic trajectory’.[23] With Malick, such a trajectory – key for the representation of lateness – is present with the body of Vietnam films as sub-genre of the war movie, and with its historic subject matter viewed in hindsight.

Run Lola Run

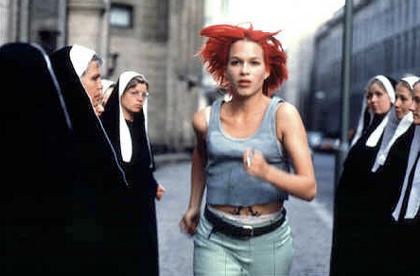

Tykwer’s film Run Lola Run celebrates the ultra modernity of post-unification Berlin, ‘arguably the iconic millennial city.’[24] Its own narrative ‘resonates with some of the most prevalent Berlin discourses at the turn of the millennium.’[25] It locates the new, post-unification Berlin within a broader time spectrum, reflecting both this city and the cinematic precursors of Lola as a big city film.[26] Beyond its more global accessibility, it can also be read as a millennial glance back at this direction of German cinema, with inbuilt markers of a whole tradition. Some motivic examples of this: the spiral rotating figure in a shop window (M [Germany 1931];Berlin, Sinfonie der Grossstadt [Germany 1927]); the blind woman who alone ‘sees’ the tramp with the bag (cf. the blind ‘hearer’ rather than ‘see-er’ in M); Lola’s laying on of hands to restore her putative father in the ambulance (an early scene in Wings of Desire [Germany/France 1987]).[27] Beyond this stylistic panorama, Run Lola Run also gives an overview of the technological possibilities developed by film during the twentieth century.[28] Of all the directors treated here, Tykwer is most attuned to the ‘Zeitgeist’, when the ‘Zeit’, the age, is technologically advanced. The incursion of cartoon and animation figures complement the backward gaze, and position this film on the threshold between conventional cinematography, and computer-generated images.

Film history here is characterized by a mise-en-abîme effect. Lola’s capacity to shatter glass with her voice, indelibly etched on the viewer’s eardrums by her primal whoop in the casino, evokes Günter Grass’ figure Oskar in The Tin Drum. But even it of course has its special place in cinema history, with Schlöndorff’s adaptation of the source novel winning an Oscar. Novel and film traditions converge, just as they do with Grass’ acknowledged mentor, Alexander Döblin. Like the ‘and then…’ alternative sequences in Tykwer’s film, Döblin’s big city novel Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929) imagines the future of peripheral figures. This dispenses with all classical notions of narrative logic and economy, while both endowing Döblin’s omniscient narrator with visionary powers, and foregrounding the performance aspects of his narration. These accents clearly apply equally well to Tykwer’s film. Döblin’s assembly of adjacent facets of Berlin life, almost as a verbal diorama, finds its postmodern equivalent in Tykwer’s film with three variations of the one story in the film’s three chapters. These divisions in turn provide a modern gloss on the cinema’s observance of Greek drama unities of time and place in Zinnemann’s High Noon (USA 1952), the countdown in real time to the noonday shootout. Tykwer’s Low Noon (the botched gun episode at the supermarket) operates with an impossible real time – in the profilmic Berlin Lola could not cover this ground in the time available. The very structure of three variations on the one story line, the last version being closest to a fairytale, evokes the impossibility of real time as linear progression, calling for a further reappraisal of lateness as a chronological category. But the variations on its own core narrative also transport the film’s intertexts into the realm of a truly future-focussed Janus-face, the hypertext.

The embedding of film history in Tykwer’s film corresponds to the archaeology inherent in any Berlin setting, one on which films like Goodbye Lenin also draw creatively. The layers of history simultaneously coexisting in countless Berlin buildings (the ultimate subversion of the city’s division across decades) balance digital effects which are ahistorical in their referentiality, but of course strong markers of a stage of film history. This mise-en-abîme of a century of film technology encapsulates the potential of that century’s new directions. It demands new styles of story-telling. But in roving across film’s pre-digital age, it also evokes the potential loss of history. The depiction of Berlin, both technically and historically, embodies a late or at least an advanced style in its representation, in keeping with Berlin’s old/new status as capital of a unified nation. Berlin is no longer a microcosm of a problematic nation divided into two states. Instead, with a pulsing soundtrack that in turn situates Berlin as a world metropolis, in this case the hub of German techno music, the city is the natural setting for youth culture. Berlin, of all contemporary cities, is available for ‘transcultural appropriation and hybridization’.[29] These are ramifications of contemporary history, well beyond the aesthetics of lateness, which tilt the millennial balance in a film like Lola in favour of future developments.

Mulholland Drive

Just ahead of David Lynch’s film Mulholland Drive, a book appeared whose subtitle it could well have shared, David Thomson’s Beneath Mulholland: Thoughts on Hollywood and its Ghosts (N.Y.: Vintage Books, 1998). The graveyard of Hollywood yields up its revenants with Lynch, but their restless presence is felt not so much through the reembodiment of stars, as through the haunting disturbance of genres. Where Run Lola Run functioned as an exhilarating Berlin film museum, complete with a futuristic pavilion, Lynch’s film functions as a waxworks of Hollywood, to take over a term from Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (USA 1950). With its quintessential exposé of the underbelly of Hollywood, Wilder’s film is strongly present behind Lynch’s, not least with its story of a faded star on the skids. With Lynch, both Sunset Blvd. and Mulholland Drive recur as street signs, while the former also locates one outlet of a diner chain called ‘Winkies’ (a reference to The Wizard of Oz [USA 1939], and obliquely to Eyes Wide Shut (UK/USA 1999], both of them ritualized dreamscapes).[30] Signage altogether is important, with the letters ‘HOLLYWOOD’ sprawling across the hills behind LA, sometimes framed by immense palms bordering the real Mulholland Drive. However the sense is never of documenting a place or an industry, but of the liminal space between reality and illusion. That space opens up in the first minutes of a long film with the disorientation of Rita/Gilda as sole survivor of the car crash. Mulholland Drive was her destination, and her amnesia amidst the ghouls signals Hollywood’s self-reappraisal at the end of a century of exhausted genres.[31]

Hollywood always was self-reflexive. But here that layer extends far beyond Hollywood. After a brief opening sequence to which we shall return, we see a stretch limo driving along Mulholland Drive. The men in the front threaten the woman in the backseat with a gun, but they are the ones to die, when another car comes hurtling round a bend, with wildly shouting youngsters on its roof, and crashes into the limo. The careering car and exuberant youths echo the framing of Antonioni’s Blow Up (UK/Italy/USA 1966), whose ending staged a mimed tennis game, one lent credence by the sound of a ball on a racquet and the camera tracking the trajectory of an invisible ball. European cinema serves Lynch as a different entry point to illusion, a different Dream Factory. The primacy of sound over sight in Antonioni foretells the central scene of Lynch’s film, set at a nightclub called Silenzio. This self-contradictory word, auratically whispered in a final frame by the blue-wigged figure in the gallery/gods, has the final say in Lynch’s long film, just as it does in Godard’s Contempt.[32]

Godard staged a filming of Homer’s Odyssey; an Italian crew shoots on Capri, and Fritz Lang directs, the perfect embodiment of the European/Hollywood axis. The American producer (played by Jack Palance) holds art films in contempt and hires a writer to commercialize the picture, the very tendency which had driven Lang back to Europe. As an instruction to the film-crew, the word ‘Silenzio’ prepares for the shoot itself, which never comes – the camera gaze extends westwards across an impossibly blue expanse of water, looking for the homecoming hero, while Ithaca, rather than being accessible to the lens, is in real geography hundreds of kilometres to the east of the camera. So Godard stages a classical European myth, originally in European film hands, but bought out by American money; his own film is basically the evacuation of the myths of storytelling and of filmmaking. Lynch stages a classical American myth – bright-eyed young starlet trying out in Hollywood. But the casting of the film-within-his-film is taken out of the director’s hands, and the framing by European cinema allusions inverts the power balance hanging over Godard’s film. Where the Odysseus of mythology outsmarted the Cyclops as ‘no one’, Lynch’s wanderer has lost her identity through amnesia, assuming the name ‘Rita’ from a poster of the star in Gilda (USA 1946).

Godard’s film was already situated in the domain of lateness, the endpoint of reliable storytellers inheriting myths; Lynch’s plumbs psychological depths and narrative fragmentation far beyond the dissection of Hollywood in Sunset Boulevard (USA 1950). But his newer medium also transmits to the very process of storytelling itself: “The nonlinear narrative of Mulholland Drive further suggests that the technologies of virtual reality feed back into the culture to change how stories are conceived and created”.[33] This complements a revue of genre history.[34] Beyond its psychological suspense, the film remixes strands of classical genres, starting with the musical. The film opens with 50s jitterbug dancing, already fractured visually and spatially, from which the Naomi Watts figure plus her two elderly guardians emerge as white blurs (after-images of a photo negative). This patterning technique recurs at the end of the sequence, the figures now being the two female leads, whose white silhouettes yield to the blue-wigged figure. Music then becomes central to the choice of a female lead imposed on the director, and finally there’s the Silenzio nightclub scene, where a Roy Orbison classic is rendered in Spanish, and what seems to be a live performance continues beyond the collapse of the singer, the object of the cinematic gaze. But other genres also proliferate. A figure called simply ‘The Cowboy’ makes a cryptic entry, meeting the director out on an isolated part of Mulholland Drive, and a still more cryptic re-entry later. There is considerable farcical humour in the film, mostly relating to genre expectations that are aroused not least by the soundtrack.

From a mid-20th century starting point, the film fans out in two directions, forwards to the end of the century via the 60s European allusions, and backwards to ‘Silenzio’, cinema’s acoustic origins in the silent era, and visual origins in the magic of Georges Méliès. Rather than opposite ends of a historical arc, these stages of cinema history are linked as a continuous spectrum, with the turn of the millennium also being roughly the cusp for digital technology. As Allister Mactaggart puts it a new book on Lynch: “the development of digital technology, as many commentators remark, permits the reinvestigation, from another vantage point, of earlier forms of cinematic technology and production as a means of understanding, in light of changes in technology, what earlier forms of cinematic cultures were doing.”[35] This aspect of Mulholland Drive, its nomadic sampling of genres in a retrospective view of 20th century film, is not an isolated example of lateness, thus conceived.[36]

Conclusion

The celebratory citation of other directors and genres characterizes the films considered here by Malick, Tykwer and Lynch, and not by them alone, partly as a legitimation of film history as a part of broader history. These are high profile, largely independent directors. But their medium is from the outset a collaborative one, at a skew to early Romanticism’s notion of ‘the interior genius of the creative individual’, and their citation of others is remote from an ‘imitation of others’. The phenomenon of lateness thematized by these directors is indeed ‘a product of artistic history’,[37] but in the sense of being an assertion of artistic history as history, as claimed above. In this sense, lateness in film can be a useful notion when approaching an epoch. And the examples chosen here, straddling the year 2000, show a more complex take on history, and on film history, than the dystopias of millennial fantasy.

Endnotes

[1] Even this category is unusual in Film Studies. One exception is Devin Orgeron, Road Movies: from Muybridge and Méliès to Lynch and Kiarostami (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 155-56.

[2] An image also chosen by Laura Mulvey in her article “Passing time: reflections on cinema from a new technological age”, Screen 45:2 (Summer 2004), 142-55. She applies it in particular to digital technology as bridging the old and the new. Mulvey also sketches in the synchronicity of the century of cinema and the impending millennium, while exploring quite different issues, via altogether different film examples.

[3] Kirsten Moana Thompson, Apocalyptic Dread: American Film at the Turn of the Millennium (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007), 1.

[4] Madman DVD (2007) – MMA2586.

[5] Leon Botstein, “Music in History: The Perils of Method in Reception History”, The Musical Quarterly 89/1 (Spring 2006), 4. Even within musicology, and with implications beyond it, such ‘fashionable concern’ has not gone unquestioned. Joseph N. Straus writes: “Milton Babbitt and George Perle, for example, are still productive in their 90s, but […] I am not aware that anyone has identified a distinctive late style for either of them”. See Straus’ article ‘Disability and ‘Late Style’ in Music’, Journal of Musicology 25/1 (Winter, 2008), 4.

[6] One need only consider the relatively even output of a Röhmer throughout a long career, or the likelihood that the director of Hiroshima mon amour and Last Year at Marienbad might some decades later turn to the genre of the musical.

[7] See George Kouvaros, Famous Faces Yet Not Themselves: The Misfits and Icons of Postwar America(Minneapolis: Uni. of Minnesota Press, 2010).

[8] Robert Stam et al., New Vocabularies in Film Semiotics: Structuralism, Post-structuralism and Beyond(London: Routledge, 1992), 204.

[9] Hermann Broch’s view of lateness combined the epochal with the individual – cf. Gordon McMullan, Shakespeare and the Idea of Late Writing: Authorship in the Proximity of Death (Cambridge: CUP, 2007), 274. See Broch’s ‘The Style of the Mythical Age’, intro. essay to Rachel Bespaloff, On the Iliad, trans. Mary McCarthy (N.Y.: Pantheon, 1947).

[10] Preserving Petersburg: History, Memory, Nostalgia, ed. Helena Goscilo and Stephen M. Norris (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2008), xvi. The film appeared (2002) in the year before the city’s tercentenary celebrations.

[11] This film has frequently been read in terms of Ostalgie, of an unreflective view of E. Germany’s past. For a counterview see my ‘Goodbye Lenin (2003): History in the Subjunctive’, Rethinking History 10/2 (June 2006), 221-237.

[12] Edward W. Said, On Late Style (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), 45: “Like Adorno, Strauss is a figure of superannuation, a late-nineteenth-century essentially romantic composer living and writing well past his real period, exacerbating his already-unsynchronized idiom by moving stubbornly even further back in time to the eighteenth century.”

[13] An article by Deborah Crisp and myself, ‘Chiming the Hours: a Philip Glass soundtrack’, Music and the Moving Image 3/2 (Summer 2010), explores this film in far greater detail.

[14] Mikhail Iampolski, The Memory of Tiresias: Intertextuality and Film, transl. Harsha Ram (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 163.

[15] Simon Critchley, afterword to Things Merely are: Philosophy in the Poetry of Wallace Stevens (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), 100. For an overview of Malick’s work, see Adrian Martin, ‘Things to Look Into: The Cinema of Terrence Malick’, The Best Australian Essays of 2006, ed. Drusilla Modjeska (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2006), 341-48.

[16] Gran Torino is an intriguing example of ground covered in this paper combined with so much else – a look back at the war movie genre with glimmerings of an Eastwood-persona figure; a Western in a suburban yet transnational setting; and the strong presence of yet another genre, comedy.

[17] There are various oblique references to inversion of more familiar material in Malick. Private Dale collecting gold-filled teeth of Japanese victims or captives evokes concentration camp images with changed signs, while shooting at the feet of the Japanese reverses the balance of power, with a different antagonist, once the Americans are captured in The Deer Hunter. The opening question, ‘This great evil, where’s it come from?’ must look different in the wake of Hiroshima, the vantage point of Malick’s viewers, but not the historical position of his players.

[18] The gap was less, but the phenomenon similar with the better known Vietnam films.

[19] See Randall Halle, German Film after Germany: Towards a Transnational Aesthetic (Urbana and Chicago: Uni. of Illinois Press, 2008), 98: “With the emergence of the transnational era and the destabilization of national identity, why is it that some of the most successful historical films depict that last moment of national antagonism? Why is it that exactly the period of national division and aggression comes to offer material for European transcultural filmmaking? This is what is most profoundly different about the transnational aesthetic and bears closer examination.”

[20] And in fact Tall himself is not immune to the glories of nature, and their transmutation into culture, citing Homer’s ‘rosy-fingered dawn’ as something to have survived his military academy training.

[21] McMullan, 62.

[22] The dialogue is not subtitled.

[23] On Late Style, 159.

[24] Reimer, Robert C. et al., German Culture Through Film (Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing, 2005), 222.

[25] Reimer, 219.

[26] This section draws on the chapter ‘In the Eye of the Story: Film, Music, Narrative’, in Reading Images, Viewing Texts: Crossdisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Louise Maurer and Roger Hillman (Berne: Peter Lang, 2006), 158-160.

[27] For an intriguing comparison with Murnau’s Nosferatu, see Michelle Langford, ‘Lola and the Vampire: Technologies of Time and Movement in German Cinema’, in Cinema and Technology: Cultures, Theories, Practices, ed. Bruce Bennett et al. (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 187-200.

[28] See Christine Haase, ‘You Can Run, but You Can’t Hide: Transcultural Filmmaking in Run Lola Run (1998)’, in Light Motives, ed. Randall Halle and Margaret McCarthy (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003), 413, n. 1: “The film offers almost every trick in the bag in terms of visuals: Tykwer makes use of animated sequences, still photography, and black-and-white footage; he intersperses his 35mm film with grainy video shots, slow and fast motion, and split screens; and he mixes together a barrage of diverse camera angles and cuts, all of which are edited dramatically for tempo and “jolt value”.”

[29] Haase, ibid., 397.

[30] And in the latter instance a further case of ‘lateness’, with Kubrick’s reworking of Schnitzler’s novella, which had long fascinated him, delayed till his own lateness and that of his century.

[31] See Joseph Natoli, Speeding to the Millennium: Film and Culture 1993-1995 (Albany: SUNY Press, 1998), 14: “The real millennium is not only anticipated, it is already co-opted, depleted, worn out. That there is thus nothing ahead but re-runs becomes itself our special twentieth century contribution to the vibe of fin de siècle.” This is recycling of a different order to that of postmodernism.

[32] For plot parallels between the two films, see http://www.mulholland-drive.net/studies/contempt.htm.

[33] N. Katherine Hayles and Nicholas Gessler, ‘The Slipstream of Mixed Reality: Unstable Ontologies and Semiotic Markers in The Thirteenth Floor, Dark City, and Mulholland Drive’, Publications of the Modern Language Association 119/3 (May 2004), 497.

[34] A characteristic shared with Tykwer’s film, which combines a love story with a gangster story, a big city story, a fairytale, but above all a video game. On genre aspects of Lynch’s film, see Debra Shostak, ‘Dancing in Hollywood’s Blue Box: Genre and Screen Memories in Mulholland Drive’, Post Script: Essays in Film and the Humanities 28/1 (Fall 2008), 3-21.

[35] Allister Mactaggart, The Film Paintings of David Lynch: Challenging Film Theory (Intellect: Bristol, UK, 2010), 73.

[36] Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge, released the same year, parades new media and digital technology alongside its celebration of the melos of melodrama. Just as earlier cinema is present, with the moon of Méliès’Trip to the Moon, the musical genre is surveyed right up to Bollywood, with a backwards excursion to Verdi’s La Traviata.

[37] McMullan, 138, with reference to 19th century musicology.

Created on: Wednesday, 1 September 2010