Ford At Fox

Part Two (a)

A Brief(er) Introduction

Born Reckless (1930)

– Addendum: Cast and Character Issues

Up The River (1930)

What would you think of an architect who arrived at his building wondering where to put the staircase? You don’t ‘compose’ a film on the set, you put a predesigned composition on film. It is wrong to liken a director to an author. He is more like an architect, if he is creative. An architect conceives his plan from a given premise – the purpose of the building, its size, the terrain. If he is clever, he can do something creative within these limitations.

John Ford, interviewed by Jean Mitry[1]

A Brief(er) Introduction

For me, the films in this part of Ford’s career at Fox in part document the director’s initial encounters with sound. Some of these are pretty interesting, and I am particularly sorry the The Black Watch (1929) is not in the Ford At Fox box set, because Gallagher says it makes inventive use of sound. I think that ambitious directors of this period tended to use sound flamboyantly early on, and in the films considered here it seems obvious that Ford paid pretty close attention to the contribution that sound could make in constructing a fictional diegesis. Sergei Eisenstein was in the United States and Mexico from 1928 to 1932, much of the time in Hollywood. Eisenstein had signed a well-known “Statement on Sound” (1928) that advocated using the soundtrack “dialectically”, that is, not always to underwrite what was going on onscreen. I wonder whether Ford and Eisenstein met. If they did, what did they talk about and if not, why not?

William Fox had a particular interest in sound-on-film technology. In converting to sound, he and Winfield Sheehan, Fox’s head of production, made Fox News Service into Fox Movietone News, cornering the sound newsreel market for a time and building one of the most successful newsreel operations in the world. The studio, however, moved fairly late into other talking productions. A John Ford picture, Napoleon’s Barber, was featured on the studio’s first all-talking program at the Roxy in 1928.[2] This three-reeler, less than one third the length of Hangman’s House, is now apparently lost. Ford made use of the studio’s newsreel-developed expertise with location sound recording for one short sequence and later claimed to have been the first person who “ever went outside with a sound system” (Bogdanovich 50). To Bogdanovich he pooh-pooled the idea that sound made much difference to the way he worked, but there is evidence in some of the films in this set that someone associated with Ford’s productions paid a great deal of attention to what we would call sound design.[3]

In April of 1929 William Fox bought a controlling interest in the Loew’s cinema chain, an aggressive expansion which threatened to upset the balance of power in Hollywood at MGM’s expense. In July of that year he suffered a serious automobile accident in which his chauffeur was killed, followed by three months in the hospital.[4] In October the stock market crashed. In November the Hoover government instituted an anti-trust action against Fox. After some tumultuous battling in which Winfield Sheehan, who had been with Fox since 1912, threw in his lot with Fox’s opponents, William Fox was forced out of the company in April 1930. Three presidents followed in quick succession, culminating with Sidney Kent, whose tenure began in 1932. Kent, quite reasonably, was suspicious of Sheehan, a man with a reputation as something of a dictator as well as a turncoat,[5] and devoted considerable time and effort to infighting with him. Sheehan finally took a golden handshake in 1935, when Kent made the deal with Joseph Schenck (chairman of the board) and Darryl Zanuck (head of production) that created 20th Century Fox.[6]

Fox Films did not make all that many big box office hits up to 1935 – a serious failing for which Winfield Sheehan is usually held responsible. It seems reasonable to hypothesise that all the feuding and fussing and fighting also had something to do with it. For example, in the conversion to all-talking production, Fox instituted a “two director” system that lasted for several years. Directors who could claim some stage experience were hired to supplement the presumably limited talents of veterans like Ford, almost always to bad effect. I think it may have been in response to what would surely have been a pretty dismal working atmosphere that Ford began to get himself loaned out in 1931 (he made six features elsewhere during the period covered by this section of the review). It also looks like he was either resisting doing westerns or that Raoul Walsh had become the studio’s big-budget western specialist. To make matters worse, Ford had not directed a real hit since 1928’s Four Sons and none of his films for Fox look comfortable or accomplished until 1933’s Pilgrimage.

At any rate, and for whatever reasons, the first few years of sound at Fox do not seem to have proved congenial to John Ford, so I guess that I don’t miss Salute (1929), or The Brat (1931), which Gallagher says do survive in more or less complete sound prints, much less Men Without Women (1930) a complete print of which appears to survive only in a silent version.[7] But, as I said earlier, I do wish I could have the opportunity to see The Black Watch (1929).

Considering the Depression and its effect on the American imagination at the time, maybe it is not so surprising to find that Ford’s Fox films during the early sound period are so focussed on communities. Or perhaps what I mean is that it is not surprising that at this time Ford, of all directors, would have focussed so much on small communities, functional and dysfunctional, and their relations with men and women of virtu, functional and dysfunctional.

Gallagher has a lot of time for the films made during the latter part of what he calls Ford’s “Age of Introspection”; that is, from Arrowsmith (1931) to The Whole Town’s Talking (1935), years to be covered in Part Two (b) of this review. He sees them as exemplary products of Ford’s “polyphonic” style, which will be discussed a little in conjunction with Seas Beneath (1931). In keeping with his insistence on the importance of the dark or critical side of Ford’s vision, Gallagher stresses the ways in which these films show a society that “is insular, static, misanthropic, and oppressive, every individual victim to determinist forces” and says that Ford’s heroic figures

find themselves ridiculous and destructive, and turn introspective. Their alienation symbolizes the common woe, serves to mature and reintegrate them, but only gradually becomes a positive force for altering social rot. . . Only with Hannah, then more fully with Will Rogers, in Doctor Bull and Judge Priest, does the Fordian hero appear, as one capable of containing the contradictions that in earlier heroes threatened sanity and demanded resolution. . . one whose knowledge of right and wrong transcends ordinary human limits and who single-handedly elevates his community out of its sloughs of intolerance and onto a higher moral plane. Outside normal human history, he is generally celibate. (85)

Because Gallagher does not here stress the ways in which the men and women in these movies distance or separate themselves from the communities to which they are attached (which he does do in his analyses of individual films), this portrait of “the Fordian hero” seems to me to have rather disturbing fascist overtones. But then, it is also the case that there are a lot of that brand of neo-fascist hero around in the popular cinema of these, and most other, years. There are some pretty close correlatives in Born Reckless, Up The River and Seas Beneath, movies which precede the period Gallagher is describing. I think that what tends to separate Ford’s conventional protagonists from proper conventional fascist protagonists is precisely their ability (not to mention the film’s ability) to recognise their own ridiculousness and/or futility, their comic aspect. Here the political importance of comedy is its finite levelling tendency: what it does to ambition, self-esteem, absolutism of any sort. The larger achievements of any of Ford’s protagonists are, in a sense, always by-products of specific goals set in and for specific circumstances. I think this is the quality he, and many others of his generation, admired so much in Abraham Lincoln.

Finally, five of the films from the 1930-35 period included in the Ford At Fox box set represent a kind of private internal dialogue on “race” couched in the conventions of the day. Up the River is the first of those films and is discussed here. I believe Ford thought of “race” in terms that would be understood these days as “ethnicity” (a word which, like “sexuality”, often has an unacknowledged biological component: people are compelled against their wills/better judgements/social pressures to adopt certain specific formal responses to social circumstances). I guess in 2009 the ways in which an Irish-American director dealt with African-Americans during the 1930s may be of some interest.

*****

Born Reckless (1930)

[See addendum: Cast and Character Issues]

This is supposed to be a gangster movie, but it is a gangster movie in the way that certain pre-World War I westerns were westerns. The gangster genre as we have come to understand it is overshadowed here, as it is in Alibi (West 1929) and Bad Company (Garnett 1931), by other melodramatic conventions. Indeed, it is only with some experience of movies like these (and Up The River) that it is possible to properly appreciate what Little Caesar (LeRoy 1931) and, particularly, The Public Enemy (Wellman 1931) did to differentiate a gangster movie from any old melodrama about a criminal.[8]

Born Reckless is based on a novel, Louis Beretti, written by Donald Henderson Clarke and published the previous year. Dudley Nichols is credited with “screenplay and dialogue”, but the film unspools very much as though it might have been based on a play – as was the case for Hangman’s House. There are three signposted “acts” which in turn seem to be divided into “scenes” that take place within certain locations (that is, there is not much cutting between locations within any given narrative episode).

The DVD is particularly praiseworthy, with good crisp images. Early sound films traditionally suffer from tinny soundtracks. The soundtrack for Born Reckless seems to have been treated very well indeed. The original sound recording seems inadequate, with lines (almost) dropping out whenever actors turn their heads or change their voice registers. This and other deficiencies in practice or equipment cannot, and ought not, be entirely overcome. But it seems to me that what there was to work with has been well reproduced and properly enhanced for DVD release, so that one can with some effort hear pretty much all that it was intended that we hear.

When he was interviewed by Bogdanovich for the latter’s John Ford book, the director said that the story for this film was not good, but that he was interested in the baseball game played by the American troops in France, which he put in for comedy (the game hardly exists in the current print, and other sources say he claimed it was cut out). Ford says, “in those days, when the scripts were dull, the best you could do was to try to get some comedy into it”, which suggests he may have read some of Howard Hawks’ interviews. His reasons for thinking the story was not good seem to have to do with mixing genres: “something about gangsters – and in the middle of the picture they go off to war” (52). Yet, taken seriously, a story that mixes comedy and melodrama in an small community (an urban neighbourhood) and structured around a central figure who is himself a mixture of virtue and vice (an honourable gangster, a good bad man) … that is a pretty standard Ford formula, much in evidence in his next Fox picture, Up The River.

The question is, why is this such a dull, bad movie? Is it just a question of a genre (gangster) and a setting (urban multi-ethnic community) that did not interest Ford? Perhaps Ford was put off by Louis Beretti’s treatment of his family, which he deceives and patronises. Beretti’s mother (Ferike Boros) is cut from the same conventional cloth as Mother Bernie in Four Sons, but she gets no respect from the story and Beretti tricks her into providing an alibi for members of the gang. Or perhaps it is simpler than that: merely the result of a raft of truly terrible performances, especially Edmund Lowe’s as Louis Beretti.

Ford told Bogdanovich a story about finding his “friend”, Andrew Bennison, who had been hired “to rehearse the actors”, drunk on the set. This story, true or not, is probably intended to be an alibi for all that very stiff acting (124). Gallagher opines that, “Andrew Bennison may have added to Born Reckless’s woodenness”, but does not say why we should think so (618, n145).

“Staged by Andrew Bennison” is what the opening titles say of that man’s contribution to the film. He has another such directing credit on a Ford film, Men Without Women (“stage director”). Why was Bennison chosen to “stage” early sound films? The word “stage” suggests that he must have had some experience with directing for the stage, but at this point most of what I know about the man has directly to do with his career in the movies. In the movies he was mainly a screenwriter, and he has a writing credit on an earlier Ford Fox film, Strong Boy (1929). Other pertinent writing credits include Defying The Law (Bracken 1924), which deals with Italian-Americans, The Wizard (Rosson 1927), which might be an interesting horror thriller, Air Circus (Hawks 1928), and Captain Lash (Blystone 1929), a Victor McLaglen vehicle using the same initial plot premise as Eugene O’Neil’s The Hairy Ape. Ford’s anecdote would seem to suggest that perhaps his “friend” was at the tail end of a useful working life. Bennison does not seem to have worked with Ford again, and his film directing days were virtually over. However, in 1930 he was still many years away from his career’s lowest point, if he ever reached it. He died twelve years later, still in the business – having spent 1934-39 writing Three Stooges and Johnny Mack Brown vehicles before things turned slightly up just before the beginning of the war (Pot O’ Gold, 1941). Ford’s comment obviously provides a frame for interpreting Bennison’s career as a downward alcoholic spiral, which may be a good reason for not doing just that.

Surely Ford ought to have taken some responsibility for the performances. There is Hangman’s House, a silent film with performances just as stilted, if not more stilted, than Born Reckless. The “serious” parts of Up The River, Seas Beneath and Pilgrimage are in the same performance register, if not quite so excruciating. Acting style alone is not what is in question. An old fashioned melodramatic and theatrical acting style is much more bearable in such films as Morocco (von Sternberg 1930), The Big Trail (Walsh 1930), Madame Satan (De Mille 1930), Les croix de bois (Bernard 1932), La chienne (Renoir 1931), Tell England (Asquith 1931), Hindle Wakes(Elvey 1931), Westfront 1918 (Pabst 1930), and even suits the many horror films of the period. The problem is the film’s articulation of that style, and it is a problem that it is evident in other Ford films of the thirties. Even as late as The Lost Patrol (1934) and Mary of Scotland (1936), the director was not always getting convincing performances from actors in the studio.

At the centre of the acting problem is Edmund Lowe. I don’t think there is anything that he does right in this movie, and when you’ve got a one-dimensional wooden actor as the focus of a film that has been written about a complex, changeable (if stupid) character, you are signed on to a death ship. Even in the military scenes, where he is conspicuously more relaxed, Lowe delivers each line as though he had just laboriously hand-lettered it onto his palm. And the lines themselves are no help either. I can’t help mentally comparing Lowe’s characterisation with Robert Armstrong’s similar character, Dude, in Tay Garnett’s 1929 Oh, Yeah?, but that’s not really fair since Oh, Yeah? is just flat out an extraordinary movie, and Born Reckless is not.

Louis: “Frank was the kind of a guy you would go the limit for”. Note the fist, but honi soit qui mal y pense. This is a John Ford movie.

Gallagher hints that maybe the story is a problem. “Building up tangential incidents in Born Reckless nearly diverts us from its pointless story” (81). His plot summary reads: “New York, 1917: For publicity, a D.A. sends three burglars to war instead of “up the river.” After France, one, Louis Beretti, swears vengeance on a mobster who shot his sister’s husband, but we hear no more of that storyline. He goes to propose to Joan, but meets her fiancé; so much for love. 1920: prospering with a speakeasy, he alibis for Big Shot, who shot a stoolie. 1922: Big Shot kidnaps Joan’s child; Louis rescues her and kills Big Shot” (552).

In spite of Gallagher’s disparaging (and, as we shall see, slightly inaccurate) summary, the story is perfectly coherent, and surely would warrant some positive comment if it had, for example, been made in France or Italy after the Second World War, since it plays with the cynicism and idealism engendered by war throughout its length. Indeed, it is not really all that easy to find as many “tangential incidents” as Gallagher implies, outside of the war sequence itself.

It seems to me that Gallagher has chosen to treat the film story as though Beretti’s character is not its central concern. But the story is about Beretti’s combination of goodness and badness, his two kinds of honour (not much different from a samurai’s giri and ninjo), his loyalty to friends and to an intuitively-derived code evoked by love and service – that is, it has the same ethical polarities as 3 Bad Men (which is a film Gallagher doesn’t like as much as he ought to). Moreover, the narrative structures its relations very much the same way as Just Pals and Doctor Bull, two of Ford’s most successful films from these early years. That is, there is a dialogic relation between the protagonist’s character and its milieu, in which each is shown refracted by the other: Beretti as both product and shaper of what is around him, and his milieu both apprehended and misapprehended by Beretti. Like many of Ford’s other films of this period, Born Reckless is a story in which an outsider finally settles a tricky relation with a small community.

Gallagher’s three-part division of the narrative into dated “acts” is the one proposed by the film’s own intertitles, but his account of what goes on in each of the acts is, I would say, deficient. Four acts works better for me, and I would summarise the events of the story somewhat differently.

In the first act, in which Beretti goes to war, a great deal of time is initially spent showing us Louis’ ambiguous relations with his own family. He deceives his parents (played by Ferike Boros and Paul Porcasi), is very protective toward his sister Rosa (Marguerite Churchill), and introduces her straight arrow boyfriend, Charlie, to his gang. O’Brien (Lee Tracy), the reporter, manipulates District Attorney Cardigan (J. Farrell MacDonald) into offering Beretti and his two companions (Eddie Gribbons, Mike Donlin) the chance to go into the army rather than serving time. This sort of deal was much celebrated in allied countries during the First World War. (C.J. Dennis’ second novel-in-verse, Ginger Mick, is directly about the same thing). However, Born Reckless goes out of its way to undercut the pompous easily-manipulable posturing of stay-at-home politicians and thus the war waged at their behest. At the first muster of new recruits Louis meets a rich kid, Frank (Frank Albertson), who has joined up because he really does want to fight for his country and who refuses the chance to become an officer. This scene also sets up Louis’ hopeless passion for Joan (Catherine Dale Owen), Frank’s sister. To end the act, two episodes are set in France. The first, which takes place in farmhouse, establishes Louis and Frank’s friendship and his continuing interest in Joan, but also shows that Louis is easily tempted by the charms of a French girl (Yola D’Avril). The second shows us “the horrors of war” in an intriguing way: as a sustained aerial attack on Beretti’s cavalry unit.

What I would call the second act brings the demobbed Louis back to the city, where he tells the D.A. that both his companions have been killed in the war and, in an ambiguous gesture, tosses him the medals that one of them has been posthumously awarded. He swears vengeance on the unnamed gangster who killed Rosa’s husband, Charlie, while he was away, but he accepts Rosa’s refusal to name the man; and he makes no subsequent effort to discover the one who did it, presumably because he respects what she has said. He visits Joan, and we learn that Frank too was killed. Just as Louis is working up the courage to declare his love, Joan’s fiancé (Randolph Scott) arrives for dinner.

By 1920 Louis has opened a nightclub, called Beretti’s, which serves as a hangout for his old gang and its boss, the Big Shot or “Big” (Warren Hymer) – although it seems Louis himself has given up active wrongdoing. Big invokes the bond of their longstanding friendship to get Louis to accompany him and Joe (Ben Bard) as they go to confront Ritzy (Paul Page), a stool pigeon who has earned Big a stretch in the big house. After Beretti leaves, Big shoots Ritzy in the back. When he rejoins Beretti, the latter argues that Big doesn’t need to croak anyone, but Big says that Ritzy didn’t keep his nose clean. Louis then dupes his mother into furnishing both of them with an alibi for the time of the murder.

The last act, which takes place two years later, begins with the Big Shot’s release from prison, having served his time on the charge resulting from Ritzy’s stooling. Louis tells Big that the gang has fallen on tough times and offers him a chance to “come in” with him at Beretti’s, but Big says that all the gang needs is a leader and that he has a plan to put them on top again. A short while afterwards an upperclass child is kidnapped and O’Brien finds out where the girl has been hidden, tipping off Big and Joe in the process. Rosa brings Joan to ask Louis for help; he discovers that the missing child is Joan’s and swears to bring her back. He journeys out to a swamp with O’Brien, rescues the child, lets two of her captors go, and is wounded by Joe, who has been hiding behind a curtain. At first Louis thinks Joe alone has organised the kidnapping, and when Joe boasts that he is going to kill Louis and that he was also the guy who killed Charlie, Louis shoots and kills him. A telephone call from Big to the hideout puts Louis wise to the fact that Big is the one behind the snatch, and he warns Big that he is coming for him. Then Louis, by now badly wounded, returns to the club and shoots it out with Big. Wounded again, he declares that he now realises that Big never knew what it really meant to keep your nose clean, and collapses. “He’ll be all right; get him a drink,” says O’Brien. But Louis looks like he is dying.

On the face of it, Born Reckless, like Hangman’s House, falls into two (very unequal) chunks: in this case, the city and the war. Carlos Clarens points out how the war scenes are very “John Ford” and how they contrast with the material about gangsters, in tone as well as setting.[9] These more fluid and “relaxed” scenes are the only ones even partly shot on location. It is also the case that almost nothing that happens in the war sequence serves to advance the plot – and that the deaths of Beretti’s companions in the war (Frank, Gibbons, Donnelly) are not shown at all. Combat is figured as an aerial attack upon a mounted cavalry unit, suggesting the vulnerability, not to say unsuitability, of cavalry in the war. I imagine that it is not entirely accidental that Louis learns something of a new code of honour by serving in a cavalry unit. This is not just a new gang; it is a gang with a direct historical and cultural connection to the old west, and one at odds with the contemporary mechanical age.

But the incidental meaninglessness of the war scenes also serves an even more abstract diegetic function: these passages imagine, they concretise, what Louis learns that can never be put into words – indeed what he himself does not realise until he is at the point of death. It occurs to me that, for an Irish-American, John Ford was awfully sceptical about the value of beautiful words or fine speeches. I think he thought that rhetorical elegance was a kind of charm antithetical to truth. This may even help to account for the raggedy nature of his films.

What happens in the city during Born Reckless happens in one limited fictional place in which events are violent and corrupted by the manipulation of appearances. War is violent and unpredictable, but no one is masquerading as something he is not. Moreover, the war takes place in “real” locations shown to us as points in passing. Within the last act there is another kind of spatial contrast: between Beretti’s bright, open, clean club and the dark, cramped, dirty shack on the river. Louis journeys out from the city and back, as he did to war, in order once again to pay a debt to society (saving a child and securing its future safety). There is a sense in these scenes of looking behind the façade that the club has made for Louis and of his having to recognise and destroy the lies of his past – which he does finally in a deliberate evocation of a classic western shoot out, complete with swinging saloon doors.

Gallagher thinks this little set-piece is a nice directorial touch. “The final shoot-out in Born Reckless (1930), mimicking a Ford western, complete with beloved bartender, is realized within a single long take — as are many action scenes in Seas Beneath. Such pyrotechnics are exceptions, rather than the rule” (81). Interesting that Gallagher would call what happens here “pyrotechnics”, when it seems much more like stylish penny-pitching and is so much in tune with the proscenium-bound style of the rest of the picture until shots are exchanged and the camera rapidly backs out of the scene (a cheap effect in two senses of the adjective).[10] However, there are a number of interesting and intelligent directorial touches in this movie. The opening sequence, right up to Beretti’s return home from “work”, is nicely handled in the kind of virtuoso neo-Weimar style common in early sound films, and there are several other nice moments, a few of which I will deal with a bit later.

According to Gallagher, Ford’s virtuoso work with sound in The Black Watch (1929) had impressed Fox studio executives (80-81). He devotes a neat endnote to a list of the sounds heard in that film that is too good not to reproduce.[11] Now, as it happens, Winfield Sheehan and William Fox were particularly interested in location sound, much featured in The Black Watch. Providentially, their idea of what to do with sound dovetailed beautifully with Ford’s penchant for location work. At the very least we can assume that Ford made use of the studio’s predilection to further his personal agenda of getting out of the studio as much as possible, which can’t have been all that easy in the earliest years of talking film production. It seems to me that it may be possible that the striking difference in quality between scenes shot in the studio and on location in so many of Ford’s films at this time has something to do with how Ford made use of Fox’s interest in location sound.

That said, the most interesting sounds in Born Reckless are associated with scenes shot in the studio. The sound design of the film seems to have received some pretty systematic attention (even though everyone knows that there was no such thing as sound design in movies before the 1950s). For example, there is a varying sound motif that occurs three times, consisting chiefly of noises made by automobile and truck horns. What makes this motif notable is that the sounds of the horns are like nothing you have heard in other movies from this period, and they appear to have been deliberately varied from instance to instance in the style of musique concrète (also, as everyone knows, a post-World War II invention).

1. About three and a half minutes in. The gang escapes.

2. About 40 minutes in. Transition to 1922.

3. About one hour and 4 minutes in. Beretti and O’Brien leave the club.

The opening scenes are quite consciously constructed to feature contrasts of loud and soft sound (marching bands, gunfire; silence, soft dialogue, background street noise). Throughout the film, dialogue overlaps black screens at the beginning and end of scenes. This kind of thing is not uncommon in early sound films, where experimentation was encouraged in order to feature the novelty of sound, but it is evidence that Ford, or someone, did pay close attention to some aspects of production, no matter what might have been said to interviewers in later life.

A limited selection of music is deployed with a certain degree of irony. “When the Caissons Go Rolling Along” plays under the opening credits and is sung a capella by a male chorus as the cavalry unit in France moves out (only to be attacked from the air soon after). The same tune underlies a shot of returning American troops at the end of the war and the film’s end title. “Over There” is played by a recruiting band as the movie opens, fading under the robbery that will soon cause Beretti and his cohorts to “volunteer”. A record of a dance band arrangement of “Over There” announces to Louis that Rosa is entertaining “her first suitor”, Charlie. (Once Louis approves of Charlie, he replaces it with a record of romantic Italian music). “Over There” crops up one more time when Brophy whistles a few bars after he finds Louis’ draft card. “Moonlight on the Wabash” is sung a capella in France by a barbershop quartet including Gibbons, and then in a dance band arrangement years later by a quartet of rotund waiters, some of whom resemble Gibbons.

There is a linking structure here, tricked up with media variations. “Caissons” (credits) to “Over There” (recruiting) to “Over There” (recording) to romantic music (recording) to “Wabash” (a capella) to “Caissons” (male chorus) to “Caissons” (return) to hot jazz (nightclub) to “Wabash” (dance orchestra plus quartet) – then, after a long music-less interval, to “Caissons” (end title). Various bugle calls are played during the short war sequence; and the use of “Caissons” to bookend the story tends to make the point that this movie is, after all, about the effects of the war. All of this music seems as well-matched to the period as those crazy automobile horns. The only false note is struck by some mid to late twenties hot jazz – instead of say, music in the manner of Art Hickman or Paul Whiteman – played under shots of what is supposed to be a floor show in 1920 at Beretti’s.

And then there is the film’s lavish use of the varieties of spoken language – another sometime feature of early thirties movies. We hear Italian (the Beretti family, Needle the bartender) and French (quite long exchanges). We hear snobby English and everyday Irish-American. Lowerclass American urban dialect provides occasions for ribbing: in the army Gibbons is chosen as a bugler because he gives his former occupation as “boy-gler” (burglar); Frank teases Louis’ pronunciation of “spurs” as “spoys”. There’s a lot of slang (even the word “yegg” is in there), and Needle uses some pig Latin when he is conveying messages to mob members.

The film is not devoid of visual style either. Blocking and framing are at times telling. Here are five examples.

Louis and Mama react as Rosa appears.

Early scenes are played out in the dining room or the parlour immediately behind it. This shot shows proscenium staging that combines the two virtual locations. When Rosa opens the door at the rear to welcome Louis home from the war one cannot but be impressed by the simplicity and efficiency of the way in which the dining room set has been expanded and “deepened” by the implied linking of the two places, the direction of the characters’ gazes, and the choreography of their movements.

Rosa, Mama and Papa witness Louis’ oath.

Shortly afterwards Louis learns of Charlie’s murder and Rosa sobs “I know what you do: more killing, more trouble, prison. Oh, I don’t want to lose anyone else that I love” and swears by the Madonna that she will not tell him who did it. Louis storms out and swears in turn that he will take revenge on the man. Although his back is to us as it was in the previous shot, he is now the object of all eyes, as Rosa was in the previous – as neatly realised “reverse shot” as you could want, and one that carries a great deal of formal and affective weight in, for example, the way in which the family blocks off the open space beyond the door.

O’Brien behind Cardigan. Can you see his lips moving?

O’Brien on the phone with Big and Joe nearby. Lee Tracy was a master of body language.

These two instances depend upon Lee Tracy’s stock reporter character, a staple of early thirties movies, called Bill O’Brien in this one. In each O’Brien is manipulating the action, much as a film director does, only without seeming to do so. In the first scene, he has just talked the District Attorney into offering Louis and his companions the chance to enlist rather than serve time – and Ford shows O’Brien as literally the man behind the D.A., practically ventriloquising him. The second is more peculiar. O’Brien is phoning his editor to tell him that he has found where the kidnapped girl has been hidden, but behind him at screen left are Big and Joe, the kidnappers. Does O’Brien know they are there? Of course: he is shown scoping them out just before he calls. Is he tipping them off? Why, yes. Will he tell Louis about them when he and Louis go to the kid’s rescue? Well, yes and no (he tells him about Joe). O’Brien gets the last line in the movie, an assurance that the collapsed Louis will be “all right”. If John Ford were Fritz Lang someone else would be writing about this kind of thing.

Poor Louis, he’s no metaphor for a film director; he’s just a sap. No wonder he walks to the kidnappers’ shack through a set like this:

Fog and branches (decorative and symbolic). A set too good to die (and see Up the River)

By the time the movie is over Louis has proved himself nothing more than an extrusion of the social fabric, a kind of cultural pseudopod. He is convinced by any dream whatever: the gang’s dream, O’Brien’s dream of rehabilitation, the dream of “Over There” (“Sherman was wrong!”), Frank’s great guy dream of noblesse oblige, his own dream of impossible love, Rosa’s postwar dream of an end to the cycle of killing, the old phoney dream of loyalties (“I’ll never ditch a guy I’ve been pals with all my life”), Brophy the cop’s dream of a lawful society (“You can’t beat old John Law, Louis, all your life”). And in the end it looks like all that the “we’ll-make-a-man-of-you” dream of the wartime cavalry did was to kit him out with a peculiarly American style of killing and dying in the service of the upper classes.

Louis: “I think I’ll go home”.

*****

Up The River (1930)

Talking to Bogdanovich, Ford seemed happy with this film, although he claimed he and William Collier Senior rewrote Maurine Watkins’ original script (52). Neither Ford nor Bogdanovich (nor Carlos Clarens) mentions how very choppy and full of plot holes the film is, but Tag Gallagher says, “the surviving print is missing numerous shots” (553), and any viewer of the DVD of the film included in the Ford At Fox set will agree that there are a lot of jumpy bits. However, it seems to me that in the first half or more of the film most of them occur within shots rather than signalling that entire shots are gone. That is, the earliest cuts are missing frames.

This is significant, because the film as it now appears is almost defiantly acentric or picaresque, zig-zagging from incident to incident, hardly glancing forward or back; viewers can never be entirely certain what the next sequence will show. There do seem to be quite a few holes in continuity, particularly in the second part when it seems that entire sequences must be missing. I suppose it could be that all those holes were created by all the stuff that was once in the movie and is no longer there, but I don’t think so. For me this holey quality gives the picture a lot of sloppy, quasi-improvised charm. I guess if I want to be totally fair about this I would say that it seems likely that certain lapses are the result of footage that has indeed been lost from this print, but that at least some of the continuity holes are likely to be just the result of how movies, especially comedies, were made back then and, yes, they do suggest an indifference amounting to contempt for well-crafted narration. In comedy, Aristotle or Eco or Cole Porter must have said, anything goes.

Given the state of the surviving material, the DVD has come up really well. The image is fairly clear and crisp, as I have come to expect from this set, and the sound is very well captured. This is the one disc where print damage is noticeable all the way through, but surely most of the people who look at the film will not be put off by that. Most of the early jumps seem to take place on the soundtrack. This is an illusion, of course, but one that maintains at least a little continuity in the viewing experience, and I imagine that is what most viewers want. By the time we get to the really big holes (a scene where con men begin their swindle of the hero’s mother and possibly a scene where some of those very con men take revenge on the major villain are both missing), the print has taught us tolerance and maybe even enlisted us in a game of filling in the gaps.

There is one extra on the disc: a stills gallery. This is the kind of extra I usually don’t bother with, but in this case it proves pretty interesting. Not that any of the stills tell us anything about missing scenes – but that only a handful are “production stills” in the sense of having been taken on the set. Most are photographer’s studio shots making use of a minimum of props and some quasi-expressionist shadows. And most of these, but by no means all, are of the film’s romantic couple: Judy (Claire Booth Luce) and Steve (Humphrey Bogart). And then the photographer makes another, utterly improbable couple out of Judy and Danny (Warren Hymer).

Ford claimed to Bogdanovich that “Sheehan refused to go to the preview”. In context this apparently means that Sheehan was miffed because Ford had turned what he (Sheehan) hoped would be “a great picture about a prison break” into a comedy (52-53), but it may also suggest that Sheehan felt the resulting picture was too sloppy to deserve his presence – or simply that he had more important things to do.

The first funny thing that happens in Up the River is that it seems to be taking up just about where Born Reckless left off. A guy named Louis escapes from prison along with his pal, played by Warren Hymer. They run to what might as well be the same car that brought Beretti and O’Brien to the kidnapper’s hideout in the previous movie, parked in the same foggy, dark set, accompanied by the same low horn tooting. There are just too many coincidences here for someone not to be chuckling in the background. Or maybe not.

The “stager” (second director) on this picture was William Collier Senior, he who helped rewrite the screenplay and who also plays Pop, the lovable, irascible coach of the prison baseball team. I would say it is clear from the evidence in the film that he got along with Ford, and it is also the case that the acting in the film is not nearly so woeful as it is in Born Reckless. However, we are still saddled with wooden romantic leads. Did Bogart ever play a juvenile lead that wasn’t wooden? If your most famous stage line were, “Tennis anyone?” I guess you would be pretty wooden too.[12] Gallagher likes Luce; he says that Ford “abandoned for once his eye-or-lower camera angle to frame her from above in three quarter profile” to call attention to her “charisma and helplessness” (81). But the shot in question is a classic DOP set up (by Joseph August) that does nothing for anyone’s “charisma”, although it does perform the narrational task of emphasising her helplessness in a slightly sadomasochistic way.[13]

What I want to say is that Ford is still having a lot of trouble with melodramatic characters. Steve and Judy are simply blanks, entirely dictated by convention. Like the couple in Hangman’s House they exist in a tangent to the world that Ford can envision. Here is an example. In prison Steve and Judy have to meet with a barred gate between them and to talk with their backs to each other. This situation creates a problem for sound recording practice at the time. Only one mike, on a boom between them, can be used. So they end up turning their heads and talking over their shoulders to speak their lines – calling attention to the limitations of the sound technology of the day in an awkward fashion, and entirely at odds with most of the rest of the film’s more casual and understated staging of dialogue scenes. There must have been fifty ways to get over this problem and make their encounters more of a piece with the rest of the film. The decision to go instead with a notably uncomfortable way of staging the scene suggests either that Ford just didn’t see the point of trying anything else or that he wanted to isolate this romantic couple and their story from the mainstream of the movie.

The case for the latter tactic is not so far-fetched as you might think. Gallagher makes a great deal of the contrast in this film between melodrama and comedy, also partly a contrast between expressionism and naturalism – and the film begins by playing up those contrasts. In the first sequence, where St. Louis (Spencer Tracy) and Danny (Hymer) escape, the first thing we see is an expressionist prison wall from the inside at night – with lights and guards patrolling, the whole deal. It is only as the scene plays out, and particularly when St. Louis speeds away in the car, stranding Danny who has already managed to complain about almost everything, that it is clear that everything in the sequence, expressionism included, is intended to contribute to its humour.

The next time the film’s dominant tone becomes melodramatic is when Steve first appears and the question of class is first canvassed (Steve, a trusty, is from an upperclass family, which is the plot machine for the story of his romance with Judy, just an ordinary kid). This time the melodrama is no joke – but it is also something we don’t care very much about because it is presented so unconvincingly. Another upperclass guy, Morris (Steve, aka Gaylord, Pendleton), who believes that his criminal career killed his mother and seems on the verge of a nervous breakdown, receives some serious, bracing advice from Steve, who reveals that he is keeping his own criminal career secret from his mother. Maybe this film, like Hangman’s House, is irritated with the perceived woes of the upperclasses. Certainly it is the case that the most convincing scene between Steve and Judy is not a melodramatic one: it takes place when Judy, not cowed even a tiny bit, is interviewed by a smitten Steve on her first day in prison. By the end of the film anything like “expressionism” has been eschewed for a flat, workmanlike visual style; and the wooden dialogue of the first part has become merely stagey (Steve and Judy have no direct contact in the latter part of the film).

Along about now you might be asking yourself what Spencer Tracy has to do with all this. After all, Up the River is his first feature, and one would not be surprised if that were one of the main reasons it was included in the Ford At Fox box set.[14] As a matter of fact, the movie is much more about St. Louis than about the romantic couple, and Tracy’s role is far more central to the film’s development than, say, McLaglen’s similar role is to Hangman’s House. There are no major problems with Tracy’s acting either. Ford apparently dug the way he moved, as well he might. I like the casual way he delivers most of his lines and the way he projects what was to become his not-quite-to-be-trusted charm.[15]

Up the River was released just five months after Born Reckless, but it is notably more assured in its sound recording. A few shots track along a group picking up key lines as they are said. The studio interior seems to have been traded for the backlot in most outdoor scenes, resulting in a flatter, less reverberating sound. All of this contributes notably to making the film feel more relaxed and casual. Of course what is lost in such a change is precisely the sense of “sound for itself” that surfaces so often in Born Reckless. Instead, Ford seems to have found a way of making sound an element of his diegetic vision, like his pictorial camera style and the way he used conventional characters, situations and other cultural tropes.

“Singing … becomes the sign of fellowship in Up the River“, writes Gallagher (301). But communal singing is a common cultural trope of the period not, as “becomes the sign of fellowship” suggests, something peculiar to Ford’s development as an artist. It recurs with dismal frequency in prison pictures. There are just two instances of group singing in this movie (one in prison); but there are also two brass bands: a “Salvation Army” type of band in which Danny finds himself, and the Bensonatta prison band, which turns out to welcome St. Louis and plays for the baseball game that climaxes the movie. These recall the military brass bands of Born Reckless and point forward to a host of brass bands in a host of John Ford movies. Those brass band are common cultural tropes too and, like communal singing and many, many other conventions of Americana, they are deployed here with Ford’s schizoid Irish-American charm – wryly, a little distanced – light years away from, say, Frank Capra’s swilling-it-up-to-the-tonsils commitment to the American cliché.

That is, Ford tends to treat such things as bands and community sing-along as subspecies of performance. During a community hayride in which everyone sings, for example, there is also a point when May and June (disconcerting twins played by Elizabeth and Helen Keating) sing “If I Had the Wings of an Angel”. The twins have already been established as self-conscious performers who always say everything in unison, and in this case their performance even has a plot-provided audience who decode the song in terms of what they know that the twins supposedly do not: Steve, St. Louis, and Danny (who is so much affected by their song that he seeks it out on the radio later on). Indeed, the hayride itself is ostentatiously laid on by the movie’s one-damn-thing-after-another narration (and announced by the twins), as a just slightly off-kilter event with just slightly naughty overtones. Surely on some level most viewers will be aware that the songs sung on the hayride are not so very different from the vaudeville performances in the section just preceding (which have a secondary meaning as cover for St. Louis and Danny’s second prison escape) – or, for that matter, from the con games practised as a way of life by St. Louis and Danny – and every other prisoner and criminal in the movie.

So Up the River is a comedy about performance; and in this case what that means is that there is nothing solid in the film except performance – appearance. When Steve returns home after being paroled, he is constantly performing his old, “real” self for his mother (Edythe Chapman), concealing where he has been and what he has done. Her life too, is a round of performances: we see her attending church, entertaining guests, taken in by a con man, summoning her son to come upstairs each evening to tell her goodnight. Gallagher calls her “pixilated” (82), but it seems to me that she is just someone fulfilling a (fictional) socio-cultural role, no more and no less wacky than Ma Beretti or Mother Bernie – or the dowager do-gooder in this movie, Mrs Massey (Louise Macintosh[16] ). As we watch Steve’s family interact with St. Louis and Danny, who are pretending to be travelling salesmen, we slowly realize that Steve’s sister (Althea Henley) seems to be ready and willing to be wooed by either while continuing to play the good daughter’s role, not all that different from Steve’s assumed role of the good son.

With this world made of performances, one would expect that the specially marked vaudeville performances would operate in paradigmatic ways, and I am not going to resist the temptation to suggest a couple of those ways. These vaudeville acts are supposed to represent prison-organised entertainment, like the entertainment organised by the English soldiers in La grande illusion (Renoir 1937). Prisoners perform for each other (and patrons like Mrs Massey) in acts that mimic music hall and vaudeville. The film coverage alternates shots of what is happening on stage with shots of the reactions of the audience of (male) prisoners. For the purposes of the story, these amateur theatricals also function as the occasion for St. Louis and Danny, a featured act, to sneak out.

As it happens, theirs is the most sensational of the performances: a knife-throwing act in which St. Louis (of course) outlines Danny’s figure in a more or less classic way (less only in that the usual subject of outlining is a woman).[17] I think it must have been important for Ford to have Hymer actually trussed on the traditional backing board while knives are actually thrown around him, because the movie goes to some lengths to make sure that we can see that this is the case, at least for most of the knives. The plot point is that once again, Danny has been taken advantage of by St Louis, but Hymer looks rather more “realistically” uncomfortable than he does “in character” uncomfortable. Danny seems to have been suspended for the length of the time that Hymer is acting as an outline marker. St Louis, on the other hand, has yet to drop his mask.

Morris, the kid that Steve talked with near the beginning of the movie, performs his character-function too – and his performance is just as conventional as theirs. He sings “M-O-T-H-E-R” (“M is for the million things she gave me”) in a tenor of course, a capella and with male vocal trio backing by the end of the song. We get a series of close up reaction shots: mostly young males, all expressing what is presumably intended as strong filial feeling. If this were a more recent film, Morris’ performance might be a sign that he has learned to mourn, but in this context he is only expressing what he knows in a way that allows others to join him in that knowledge, perhaps one way that this film understands performance itself.

I have saved the first of the vaudeville performances until the last because it directly raises the issue of race or ethnicity to which Ford returned over and over during this period. Before dealing with that performance, however, I want to discuss some other instances in which this film deals with race.

There is one humongous hole in all the cast and characters lists for Up the River I have seen so far, including Gallagher’s (552-553). A light-skinned African-American woman plays one of the women prisoners, called Jennie and Genesis in the movie. She is very savvy and is given some showy smartass business in the first half.

We see her first behind a line of young, pretty white women, most of whom seem to be blonde. They are the latest intake for the women’s section of the Bensonatta prison. Jennie darts from side to side behind the newbies, bugging her eyes and doing double-takes to whatever they happen to be saying – and they are talking a lot. One, the one furthest to our virtual right, is putting on hoity-toity airs and making out that she is somehow superior to the rest of them because of the kind of crime she is in for. Jennie reacts with awe: “The extortionist? [Beat] Honey was you in the circus?” Right then you know she is a dangerous woman.

But the most notable thing she does is puttin’ on ol’ missus (or massa) by conning Mrs Massey (get it?), who is leading a visiting delegation of upperclass white women. Take a look:

In this scene Jennie plays to all the culture’s prejudices about “good darkies” so appropriately that she takes in the younger women inmates as well (and maybe you and me – all of us prisoners of what we believe to be cultural expectations). I wish I knew who the remarkable person playing Jennie was.[18]

Such a positive, assertive portrayal of an African American is unusual in John Ford’s film, and I think that one reason Jennie is something of an exception is because she is a woman (as well as so impressive a performer). It seems to me that, in general, racial stereotyping tends to be derived from, or to produce, structures in which gender, generation and the poles of light/dark skin colour also play determining roles. Jennie is a light skinned (“mulatto”) young woman. Central to the 30s American (white male) imagination of its “racial” other is a dark skinned masculine figure that is almost invariably shown as powerless, childish, enfeebled and/or feebleminded. In Ford’s work this figure makes its most memorable and sustained impression in the films that feature Stepin Fetchit (Lincoln Perry), which will be discussed in the next part of this review. Figures of strong(er)-willed black women tend to show up, not only in Ford’s films but in the culture as a whole somewhat obsessively as if a balance had to be struck. In the same way, good older African American men (often preachers) can counterpoint sinful, idle younger men. And although I am concerned with this structuring as it appears in these movies from the 1930s, I should point out that elements of it are apparent in the recent television series, The Wire, as well – and that the axes of strong-weak, masculine-feminine, light-dark, young-old can be, and are, mapped on other fictional grids besides “race”. What makes this a racially stereotyped structure is the specific way a character like Jennie acts in a movie, which is a combination of her performance, the script of the film and the way in which scenes are directed and edited.

Without wanting to make too much of it, one can make a parallel between how Jennie acts (sassy, aware, strong, independent, performing all the time) and the way St. Louis acts. She is the closest thing to a female counterpart to the brash, admirable white con man that the film offers. Of course, there is a difference, and a significant one: for when Jennie is not acting up, she is mopping up (the floor). Nobody takes any notice of her when she is doing that. Her head is down, her back is bent. She is performing the acceptable convention. And at those times she is virtually invisible, which St. Louis never is.

But Jennie is not the only virtually invisible African American character in Up the River. There is another one, a man, and he is the object of extraordinarily concentrated racist vilification, executed at first quite casually, and then in a literally confronting scene.

This character is called Big Pete (and the actor who plays him does not appear in any credit lists either). He is as noticeably black as Jennie is noticeably light skinned. The first time he appears is also in one of the earliest scenes introducing Bensonatta Prison. The old baseball coach, Pop, and other seasoned inmates are looking over a bunch of new arrivals, probably with an eye to whether they can be used in the band or Pop’s baseball team. Pete is conspicuous in the set up, behind Pop and to the right of the screen. At first I thought, so naively, “that’s interesting, did they have integrated prisons in 1930?” and then, “He must be on the baseball team. I didn’t know Ford was so enlightened”.[19]

But all that went by the board when the scene finished with five lines of dialogue, reproduced beneath the stills from the scene below. This is a very casual, seemingly insignificant exchange that is almost gone in a flash. Its story intention is only to establish the jokey, free atmosphere of Bensonatta prison. As the exchange starts Pop looks disapprovingly at the last two emaciated white prisoners to arrive.

1. Pop: They wouldn’t even allow those kind of guys in here in my time.

2. Slim: Well, how’d they keep ’em out? Blackball ’em?

3. Pop: You know what they woulda called Big Pete in my day?

4. Slim: What?

5. Pop: A sissy.

As it has been written, blocked out and directed, this is a fairly complex exchange every line of which is intended to insult and humiliate Big Pete and, by implication, other African American males. It is complex because Pop and Slim are talking in code: “those kind of guys” “blackball” “what they would have called him” “sissy”. Big Pete’s name may be in code too. “Peter” was apparently African American slang for “little boy’s penis” at least by the 30s and may have been current in other sections of American society at the time this film was made.[20] Considering the care with which all this nastiness has been crafted, there seems good cause to understand that Big Pete’s big peter is the main reason he might have been called a “sissy” (contemporary double-meaning slang for gay male) in Pop’s day. Consider also how Pete is ignored as the lines about “those kind of guys” and “blackball” are delivered and then how Pop’s gesture towards Pete, when he uses his name, actually stops short of eye contact or direct acknowledgement. Finally, notice how Pete’s expression, even his position, remain almost unchanged throughout. The entire exchange is predicated on Big Pete’s visible invisibility and his inability to understand and/or to react to an invisible insult. This little sequence is also, I note, an instance of what Tag Gallagher calls “invisible humour” in Ford’s work (82).

Five lines, then, carefully and deliberately condense and refine much that is ugly in American racism, but there is worse to come. The very first vaudeville performance of those I discussed earlier is by a blackface act apparently known as Black and Blue, playing prisoners called Slim and Klem (at least this is what Gallagher’s credits attest). Yes, the “Slim” in the exchange above (the man on the far left of screen, balancing Big Pete) turns up as one of the members of the blackface duo. The act itself is built around novelty musical instruments and would be mildly entertaining if it were not for the blackface makeup and dialogue. What makes the act almost unbearable for me is that Ford chooses to feature Big Pete laughing uproariously in a series of reaction shots – over and over again. He does not appear in any audience reaction shots after this. In the context that this movie provides for itself, this can only be an intensification of that earlier sequence: confronted by racism in a way that one would think he could not avoid, Big Pete approves, joins in, the performance. The film humiliates him.

There is another, glancing but telling, allusion to race and invisibility later in Up the River. While St. Louis and Danny are at Steve’s house they are guests for dinner with Steve’s mother. As I have already mentioned, the dinner is interrupted by the twins and others announcing the hayride. In the process Danny is displaced from the table and cannot find another seat. Everyone is ignoring him anyway. Finally he spots a chair that is placed behind a screen in the dining room, and sits down, isolated and disconsolate (which is commonly his lot in life). He has become invisible to the others around the table.

Why is there a screen with a chair behind it in the dining room? Well, you see, Mrs Jordan, being an upperclass lady, has a black maid, who appears now and then to do necessary menial tasks that upperclass white ladies do not do (with no screen credit). Sometimes, in more formal dinners, it is convenient to have one’s servants within easy call, but to have them visibly hovering about might disconcert one’s guests. Thus the screen and the chair – and thus when Danny sits down he is literally taking the place of a subservient black woman.

The movie is humiliating Danny (again), and the parallel between Danny and Big Pete is in every way instructive. However, there is another, non-racial, side to what happens to Danny and Big Pete (and Judy) in this movie, and that is the role that humiliation plays in Ford’s vision as a whole. Humiliating one’s subordinates was a tactic employed by a surprising lot of people at the time, not just movie directors, baseball managers and bandleaders like Cecil B. DeMille and Fritz Lang, John McGraw and Rogers Hornsby, Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman. I think it was probably something they all adopted from the military. At any rate, it was characteristic of Ford’s relations with people he considered inferiors that he made them do humiliating things, often onscreen. Gallagher quotes the director as saying of his brother, Francis (who had been a film director before John), “I want to see him lashed” and says that “it was partly to humiliate Frank that Ford cast him always as a loony or drunk” (41; and see also the section of Gallagher’s book called “Building a Legend”, pp. 46-49). Ford, invisibly directing behind the camera, apparently found this sort of thing funny. But then Ford was himself a drunk who often acted like a loony; he knew he was just another mongrel bastard, like you and me. And if he was humiliating people because he actually liked doing that sort of thing, he was also helplessly weaving humiliation into the vision he was creating on screen. Visions of humiliation are tormenting because they are true and one does not want to recognise the substance of their truth. The act of humiliation and being humiliated is never straightforward. Here in particular, evil is within those who evil think.

The last shot of the movie. Honi soit qui mal y pense. This is a John Ford film.

*****

Part Two (b) will include:

Seas Beneath (1931)

[Pilgrimage (1933)]

Doctor Bull (1933)

The World Moves On (1934)

Judge Priest (1934)

[Steamboat ‘Round The Bend (1935)]

[Prisoner of Shark Island (1936)]

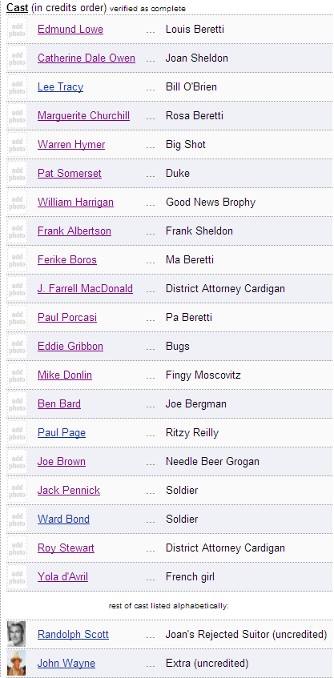

Cast and Character Issues

The level of scholarship on what one might consider the basics of Born Reckless is appalling. The printed cast and characters lists I have seen appear to derive from filmographies going back to 1948. Only one, however, actually names all its sources (Peter Bogdanavich, John Ford, University of California Press, 1968: pages 109 and 144). In this case, as in all the others I have been able to check, one name that actually appears on the film’s credits (of an actor who, I think, actually appears in the film), is not included – which means that a certain fundamental level of scholarship has not been attained.

I am seriously annoyed that the disparities between the information in the film and the information available in print and online are so wide that I feel compelled to write something about them. It is not as though Fox lacked the resources to employ a couple of cluey graduate students to produce better cast and crew credit lists derived from and referenced to existing materials. It is not as though those who have written on Ford’s films could not have done at least what I have done – with the comparatively meagre resources available to a retired academic working in Australia.

The Information in the Film

This is the fullest cast list to appear in the film: sixteen actors. Preceding this list has been the first credit title which says in part, “with Edmund Lowe as Louis Beretti and Catherine Dale Owen, Frank Albertson – Marguerite Churchill, William Harrigan – Lee Tracy, Warren Hymer”. This credit gives us a clue as to how to read the fuller cast list: that is, from left to right across (“Edmund Lowe, Catherine Dale Owen” not “Edmund Lowe, Marguerite Churchill”). In this list, however, the order of precedence has changed somewhat; Frank Albertson has slid down. His name is followed by Ilka Chase and eight others. The order of precedence might well have been significant for movie goers at the time, because they would have thought that the actors highest on the list would play characters who got the most screen time. Contemporary viewers would not necessarily have been able to identify actors like Catherine Dale Owen, William Harrigan, Frank Albertson, Warren Hymer or even Marguerite Churchill. Lowe and Lee Tracy are really the only contemporary box office names in the cast. I have seen a lot of movies from this period and the only other name on the cast list to which I was able to put a face when I first saw the movie was Ilka Chase, someone whom I had seen on television when I was much younger and she somewhat older.

The film text is the most authoritative source of the other half of “cast and characters”: the roles or characters played in the movie. Only one actor and character are linked in the film credits: Lowe and Beretti. But there are a lot of characters in Born Reckless, a lot of roles for actors to play. Here is a list of some of them derived from my viewing of the movie:

1. Louis Beretti

2. Joan Sheldon, sister to Frank Sheldon

3. Rosa Beretti, sister to Louis

4. Bill O’Brien, reporter

5. Big Shot (“Big”), gang leader

6. Good News Brophy, honest cop

7. Frank Sheldon, rich boy volunteer

8. Ma Beretti

9. Pa Beretti

10. Gibbons, arrested with Louis

11. Donnelly, arrested with Louis

12. Joe (Fleischer), hack driver

13. Joe (“Needle”), bartender at Beretti’s

14. Ritzy Reilly, a gang member with aspirations

15. “Maurice”, a gang member with an English toff’s accent

16. J. J. Cardigan, District Attorney

17. Frank’s Uncle Jim, another pompous blowhard

18. Marie (a French girl)

19. Dick Milburn, Joan’s fiancé, later husband

20. Sally, Louis’ neighbour and helper, later hatcheck girl at Beretti’s

21. Charlie (“Banks” “Four Eyes”), Rosa’s boyfriend

22. A Sergeant in charge of recruits

23. A General visiting Frank

24. An ugly soldier in France

25. A gullible socialite, taken in by “Maurice”

26. A kidnapper who warns Louis of a potential ambush

Let’s take a look at the published cast and characters lists.

The Information Available in Print and Online

The most authoritative printed cast and characters list ought to be the one that appears in The American Film Institute Catalog for 1921-1930. It is likely that this is the basis for the cast and characters list that is most often consulted these days: the one at the Internet Movie Database (IMDb).

The earliest cast and characters list that I have for this film is the one on page 33 of Présence du cinéma for March 1965. Présence 21 is one of the sources for the filmography in Bogdanovich’s book on Ford.[20] Its list is identical to the IMDb list above, even in the order in which the names appear, up to and including the credit for Joe Brown. It also includes the names of actors Roy Stewart and Ward Bond, but not the characters that they play. (And, as I have said earlier, it does not include Ilka Chase.) Bogdanovich only adds Pennick’s name and credits him and Bond with playing “soldiers”, but does not add a role for Stewart (Bogdanovich, page 124). What I am saying here is that to my knowledge there has been no substantial change in printed cast and characters lists for this film for more than forty years.

Even if Ilka Chase is still unaccountably missing, there are six actors’ names to add to the sixteen which appear on the credits:

17. J. Farrell MacDonald

18. Jack Pennick

19. Ward Bond

20. Roy Stewart

21. Yola d’Avril

22. John Wayne

Let me clear up the John Wayne thing now. I firmly believe that people more adept at Wayne-spotting have identified John Wayne in this film. I have not. This is, first, because he is not featured so prominently as he is in Hangman’s House, where it is hard to miss him in at least one scene. But it is also because I don’t care. John Wayne will be mentioned only once more in this sidebar.

Unfortunately, there are some new characters in the printed lists too. I say “unfortunately” because the discrepancy means that I will have to spend some time trying to reconcile the printed list of characters with the names or other indicators that I hear on the soundtrack of the film, for these new characters are not clearly identified with any of those I was able to derive directly from the film text.

27. Duke

28. Bugs

29. Fingy Moscovitz

30. Joe Bergman

31. Needle Beer Grogan

32. Soldier

33. Soldier

34. District Attorney Cardigan (2)

On the other hand, quite a few of the roles that I identified as occurring in the movie do not appear on the new list. This suggests there are more ennuis to come.

Making a Reasonable Cast and Character List

When I first saw Born Reckless, I recognised some actors from this period in just the way I recognise some actors from our own period: expression and content, signifier and signified were inseparable. I saw Lee Tracy’s image and heard his voice, and I knew it was Lee Tracy. In Born Reckless this was the case for Tracy, for J. Farrell MacDonald, for Ward Bond – and for Ilka Chase. It was also the case for Randolph Scott, who is credited with the film in the IMDb cast list, but not elsewhere.

I knew other actors in the film mostly by their names. I have seen films with Edmund Lowe (What Price Glory?, Dillinger 1945), Marguerite Churchill (The Big Trail , Quick Millions 1931) and Mike Donlin (The General 1927, Beggars of Life 1929), but I would not and, in the case of Donlin, did not recognise them except with extra prompting (Lowe’s credit as Beretti, Churchill’s billing, Donlin’s presence in Doctor Bull and Up The River).

I recognised another actor because of his face: Jack Pennick. Pennick has a very memorable face. That face has appeared in all the DVDs in this set so far and will likely appear in all the others as well (Pennick may be in all of Ford’s films after a certain date), but I put a name to it only in compiling this sidebar.

Born Reckless “taught me” to recognise Warren Hymer. That is, I recognised his name when I saw it in the credits and then his face and voice when I experienced them in the film, but this was the first time I can remember consciously putting the two together.

The various types of recognition of these ten actors enable me to assign them to roles in the film more or less confidently.

Edmund Lowe – Louis Beretti

Lee Tracy – Bill O’Brien

Marguerite Churchill – Rosa Beretti

Warren Hymer – Big Shot

J. Farrell MacDonald – J. J. Cardigan

Mike Donlin – one of Louis’ two companions in crime (Gibbons or Donnelly)

Ilka Chase – gullible socialite

Ward Bond – a sergeant in charge of recruits

Randolph Scott – Dick Milburn

Jack Pennick – an ugly soldier in France

However, most of the actors in this film, in any film, are not going to be recognisable to me. I have to use sources other than my memory to work out which actor’s name ought to be applied to which character. For me, and for most academic researchers into American film these days, one of the largest and most accessible resources is the Internet Movie Database, the IMDb. This means I am about to put myself in an invidious position – for the IMDb is one of the sources of this corrupted cast list, yet I will use it to check and cross-check that very list. Thus, for example, for Mike Donlin, whose name I knew because he was a famous ballplayer rejoicing in the moniker, “Turkey Mike”, I consulted the list of films that the IMDb says he appeared in and located two I could check. I found scenes in those films in which an actor appears who seemed to me to be the same as one I had seen in Born Reckless, and verified a pre-existing suspicion that he played one of the two men who were sent to the war with Louis.

The corruption in the IMDb is not confined to what it has inherited from previously corrupt cast and characters lists. Randolph Scott’s name appears only on the IMDb – which is a plus for that source, since he is definitely in the movie – but he is listed there as playing “Joan’s rejected suitor”, a character that does not exist, unless it is Louis Beretti himself. If I had not been able to identify Scott I would have questioned the IMDb’s attribution. (Scott has been identified as appearing in some pretty embarrassing movies and one ought to exercise some discretion in putting him in places where perhaps he ought not be).

In the end, however, I have tried to rely on the IMDb for this addendum in the same critical way that I strive to rely on other sources. That is, I accept its information if that information seems more or less reasonable (see the cases of Ferike Boros and Paul Porcasi below) and/or if I can cross-check what it says against an independent source (in this case, mainly DVDs to which I have access, as in the case of Donlin above).

The IMDb and its main source, The AFI Catalog, have to be taken as mostly reliable in the information provided on American films. The “corruption” in their listings is like textual “foulness” in old printed editions: errors are not the norm; they are exceptions. These sources have to be taken that way because we – or most of us anyway – have no alternative except what can be gleaned from the film itself, which may (or may not) be reliable, but is also very limited in the information it can provide. I certainly believe that those who put together The AFI Catalog tried to provide the most authoritative information about Born Reckless that they could, and I feel no qualms about accepting their judgement in cases where no strong alternative presents itself.

We are now ready to do some “reconciling”. Let me begin with the remaining ten actors in the credits: Dale Owen, Harrigan, Albertson, Boros, Porcasi, Brown, Bard, Somerset, Gribbon, and Page. I am going to assume that these actors played noticeable, if not always narratively significant, roles in the film. I am also going to assume that those who are highest on the list are the most likely to have been playing narratively significant roles.

Catherine Dale Owen surely must play something like the female “romantic lead” or else she would not be getting second billing. That character surely must be Joan Sheldon, Frank’s sister.

William Harrigan‘s last name is the same as one in a song that a lot of movie goers would have known back then, with a lyric that goes in part, “H A double R I / G A N spells Harrigan / Proud of all the Irish blood’s that’s in me”. This would be a fairish reason for assigning him the role of the Irish cop, Good News Brophy, even if no one else had done so. (As it happens, during the time I have been writing this review I have acquired a DVD of Desert Fury, a 1947 movie in which Harrigan appears and is credited with a role. There is no doubt in my mind that the same man played Brophy in 1930).

Another narratively significant character is Frank Sheldon, the rich kid. Frank Albertson does seem like a good fit for that one. He is someone I ought to be able to remember from fifties and sixties American television too, but I don’t.

Cross-checking their filmographies on the IMDb seemed to confirm what you might expect from reading their names on the movie credits: that Ferike Boros (Hungarian) and Paul Porcasi (Sicilian) were specialists in Mom and Pop European ethnic characters. I do not doubt that they played Ma and Pa Beretti.

I accept that Joe Brown plays the bartender at Beretti’s (the same guy can be spotted playing a very minor role in Up The River, which is in his IMDb filmography), but I do have some trouble with the character’s name in all the cast lists. The character is at first called “Needle” by O’Brien, but later in the film is called “Joe”. I didn’t hear a last name at all, so “Needle Beer Grogan” doesn’t quite fit.

From the very sparse visual evidence I could find about Ben Bard, I think he did play the “Joe” in the film who is first seen driving the getaway cab. But that “Joe” gives his last name as “Fleischer” to a suspicious cop. Again I didn’t hear any reason to think that his last name is really “Bergman”.

In the movie, O’Brien identifies another character, who is masquerading as “Maurice”, a member of the English aristocracy, as “Moe” and then “Co-han”, presumably “Cohen”. Later on, Beretti mentions “the Duke” to O’Brien. Pat Somerset is listed as playing “Duke”, but not “Maurice” or any of those other names, and Somerset was (supposedly) born in England and appears, with a somewhat less convincing toff accent, in Up The River. This is not what I would call a “narratively significant” role, but he does pop up more than once.

The film only distinguishes Louis’ two companions in crime after he returns from France and tells J. J. Cardigan about their deaths. At that point there is no telling “Gibbons” from “Donnelly” since they aren’t around to provide visual clues. Neither of these names, which do have to be taken as the characters’ real names, figure on anyone’s cast and characters list. However, two actors have names which are close to “Gibbons” and “Donnelly”. They are Eddie Gribbon and Mike Donlin (dealt with above). Donlin is skeletal and thus, presumably, the skeletal character is “Donnelly”. According to what I could find on the IMDb, Gribbon was a comedian with a fair list of credits and, serendipitously, I was able to locate a site that seems to have a picture of him from one of his comedies. That picture bears a close enough resemblance to the “burglar bugler” character for me to declare that he played that role, which I am equally sure was “Gibbons”.

Now this does not address the strange names given to the characters that Gribbon and Donlin are supposed to play according to all the cast lists. There is actually a “Bugs” in the movie, but he features only at the end of a telephone line. As for “Fingy Moscovitz”, go figure. Turkey Mike was never a pitcher.

Paul Page belongs in the same category as most of the others who feature in the film credits and have made it into the published cast and characters lists. I have no reason for not accepting the attribution. “Ritzy” is a narratively significant role.

There are two actors who have been added to those listed in the credits with whom I have not yet dealt.