Uploaded 1 December 2001 | Modified 11 January 2002

I. The Projectionist’s Window

There were years when I went to the cinema almost every day and maybe even twice a day, and those were the years between ’36 and the war, the years of my adolescence. It was a time when the cinema became the world for me. A different world from the one around me, but my feeling was that only what I saw on the screen possessed the properties required of a world, the fullness, the necessity, the coherence, while away from the screen were only heterogeneous elements lumped together at random, the materials of a life, mine, which seemed to me utterly formless.

Italo Calvino[1]

The opening lines of Calvino’s “A cinema-goer’s autobiography” seem to tell a familiar story, a story of growing up and moving through the world hand in hand with the image. In Calvino’s tale the cinema is no longer simply a matter of images projected on to a screen, images that duplicate a world that exists elsewhere. For a time in the narrator’s life – the years of his adolescence – the cinema becomes the world, a world different from the shapeless mass of elements and events surrounding the cinema but capable of demanding its own form of engagement. “[I]t satisfied”, Calvino goes on to observe, “a need for disorientation, for the projection of my attention into a different space, a need which I believe corresponds to a primary function of our assuming our place in the world, an indispensable stage in any character formation”. (38) For anyone with more than a passing interest in the way we understand film and its relation to history there is something beguiling about Calvino’s tale of cinematic obsession. Forming part of a series of autobiographical reflections that take in the author’s war time memories of a battle, his relationship to his father and reflections on modern Italian life, “A cinema-goer’s autobiography” provides an extraordinary account of audiences and viewing habits. It is a story of the architecture, the smells and class structures of provincial Italian cinema-going seen through eyes transfixed by the magic of 1930s Hollywood cinema. It captures the peculiar moment common to Italian cinemas of the time when the side doors of the cinema are opened during the interval between the first and second reel “and the passersby and the people sitting in the cinema would look at each other a little uneasily, as though facing an intrusion equally inconvenient to both”. (44-45) There is also an account of the powerful sense of disorientation felt when one steps out of the cinema to discover that day has turned into night:

The darkness softened the contrast between the two worlds a little, and sharpened it a little too, because it drew attention to the passing of those two hours that I hadn’t really lived, swallowed up as I was in a suspension of time, or in the duration of an imaginary life, or in a leap backwards to centuries before. (43)

Without doubt, these reveries and reflections produce their own cinematic effect. They allow us to reclaim something of the enchantment that draws us back to the cinema. And, most importantly, they also highlight the capacity of the cinema to open up a space within our lives marked not only by mystery but a relation to time in which we move forward and back simultaneously. In Calvino’s story the cinema occupies that part of ourselves in which time flows in all directions. Beginning with a reflection on his provincial childhood and moving through the years of post war adulthood, the cinema-goer occupies both ages at once: “As in the analysis of neurosis”, Calvino writes towards the end of the piece, “past and present perspectives become confused; as in the outbreak of an attack of hysteria, they are exteriorised in spectacle”. (72) Perhaps what I am trying to identify can be put quite simply. Much more than a cinema-goer’s nostalgia or enchantment with the image, Calvino’s tale is also of a spiriting away. “One does not simply observe the framed space of an effective movie fantasy”, writes Georges Toles, “one aspires to own it, to be lord of the dominion, as a child owns the secret spaces she reserves for play”.[2] Yet there is another form of relation to the image that Toles speaks of, one in which the terms of ownership are overturned. “[W]hen the movie image asserts with unaccustomed strength its own claims over you (shattering the illusion that the movie is obedient to your will, and comfortably knowable), the terms of ownership shift”. (95) In this altered form of relation, the images which move across the screen are not simply a passport for a journey elsewhere or a form of escape from the world. They also have the power to claim us, to both form our history and spirit it away.

It is this sense of dispossession whereby the circuitous time of personal memory becomes entangled with the public life of cinematic images and sounds that one can hear in Calvino’s autobiography:

The projectionist’s room had a small window that opened onto the main street and would blare out the absurd voices of the film, metallically distorted by the technology of the period, and all the more absurd thanks to the affectations of the Italian dubbing which bore no relation to any language ever spoken, past or future. And yet the very falseness of those voices must have possessed a communicative power all its own, like the sirens’ song, and every time I passed that little window I would sense the call of that other world that was the world. (44)

If we listen closely as we pass the projectionist’s window we can hear the call of this other world that Calvino speaks of and sense its attraction, the attraction of a world in which time moves forward and back. And if we pause for a few seconds outside the tiny window something else starts to take shape. In the metallically distorted din of voices and sounds are the traces of a history of cinema very different to the way we usually understand film history. This is a history of cinema understood not as a series of technological developments, institutional ruptures or individual careers. It is something both more concrete, tied to everyday experience, yet far more elusive. The history of cinema that I am referring to is, on one level, bound to a project of popular memory where the experience of cinema-going forms part of a larger social and cultural narrative. The cinema-goer looking back over the past, we often hear, is unsure as to what part of their recollection is drawn from lived experience and what part is drawn from the affective capacities of the cinema. Robert Burgoyne has recently referred to a certain anxiety or disquiet concerning the impression of an overwhelming cinematic influence over the historical imagination, a sense that “film has somehow claimed the mantle of authenticity and meaningfulness with relation to the past — not necessarily of accuracy or fidelity to the record, but of meaningfulness understood in terms of emotional and affective truth”.[3]

Cinema, he goes on to note, has the capacity to replace actual memories with a series of cinematic experiences and impressions which are “burned in” and form part of a personal archive of experience. Calvino’s story proves so illuminating precisely because it too is concerned with the nature of this experiential relationship between cinema and memory. Yet what it suggests is something quite different to Burgoyne’s assessment. In Calvino’s reflections on the life of the provincial Italian cinema-goer the image stands in for something unknown and mysterious within us, a type of memory neither fully realised nor wholly dispersed but rather resonating across the different ages of the spectator. For Calvino the power and allure of the cinema is drawn from its capacity to reconstitute both our relation to the world – woven around a series of public and personal memories – and the temporal logic through which we make sense of our lives.

For the brief span of our lifetimes, everything remains there on the screen, distressingly present; first images of eros and premonitions of death catch up with us in every dream; the end of the world began with us and shows no signs of ending; the film we thought we were merely watching is the story of our lives. (72-73)

II. Writing and Memory

The importance of understanding the cinema-goer’s relation to time and memory is also central to the work of the French film writer Jean Louis Schefer. Located to one side of any easily identifiable theoretical context, Schefer’s writings construct an account of cinematic reception that draws attention to the cinema’s capacity to produce and engage with figures and sensations that stay with us and form what he variously refers to as “the unknown center of ourselves”, an enigmatic or paradoxical body. These terms stand in for a point of unknowability in our relation to the image, an unknowability that stems directly from our unfinished relation to time and memory. Paul Smith puts it very well when he observes that the enigmatic body “constitutes ‘what is missing’ from our encounters with art objects and writing: time and memory separate us from any realizable figuration of ourselves”.[4]

If time and memory do separate us from any realizable figuration of ourselves they also inaugurate a procession of unknown figures that inhabit our relation to the cinema.

If the cinema, apart from its constant renewal in every film and each projection, can be defined by its peculiar power to produce effects of memory, then we know – and have known for several generations – that through such memory (in this case, through precise images) some part of our lives passes into our recollection of films that might be totally unrelated to the contents of our lives. (111-112)

The understanding of filmic engagement that emerges in Schefer’s work is very different to those more familiar notions based on a concept of an imaginary identification with the image or inversely a more playful ironic form of relation. In L’homme ordinaire du cinéma Schefer reconfigures the abstract notion of the subject that has dominated film theory with a consideration of the effects of memory and time. The cinematic spectator is scattered through and through by the effects of memory drawn from our conscious world but also from what Schefer describes as an interior history characterised by aphasia. “[A] lived existence”, Smith surmises, “includes a whole series of enigmatic and imperfectly formed fictional subjects in memory which go toward the experience of an individual but do not entirely cover it. We exist for ourselves, then, as a series of moving images, caught between our momentaneous experience in time and the passing of that experience into memory”.[5]

The power of cinema resides in the way it connects with that part of ourselves lost to the effects of time. As Schefer puts it, the images on screen “make an immediate pact (story, pictures, affective colors) with a part of ourselves that lives without expression; a part given over to silence and to a relative aphasia, as if it were the ultimate secret of our lives – while perhaps it really constitutes our ultimate subjecthood”. (112) When Schefer explains the motivation behind his writings on cinema, he speaks of an effort to write or give voice to an “internal history”:

I wanted to explain how the cinema stays within us as a final chamber where both the hope and the illusion of an interior history are caught: because this history does not unfold itself and yet can only – so feebly does it subsist – remain invisible, faceless, without character, but primarily without duration. [6]

For Schefer the activity of writing is where the shifting and unfinished relations of time, memory and the image are brought together in a struggle against disappearance. It brings into being a series of figures caught either too soon or too late that push writing to the brink. The writer is caught in the awkward position of moving both forward and back, unbalanced yet alert to the flickering allusive presence that is always drawing away at the same time as it leaves something behind: “It’s . . . a matter”, Schefer observes, “of lending a voice, however briefly, to a memory, to the spectacle of its effects, and to render a certain threshold tangible”. (111) In their different ways, both Schefer’s recounting of the experience of the ordinary man of the cinema and Calvino’s “A cinema-goer’s autobiography” mark a form of writing on the cinema concerned with this threshold of memory, a writing on the cinema in which the image is subject to a certain treatment or reflection that involves a combination of autobiography, third person narration and essayistic reflection and also stands in for what is unknown or cannot be comprehended in our relation to time. This is a relation to the image haunted by the possibility of aphasia yet also compulsively drawn back to the task and exigency of writing and reflecting on the experience of cinema. For both Schefer and Calvino it is writing – pushed to the brink of memory – which teaches us how we exist in relation to the image.

III. Father hunger

A machine whirls, representing simultaneous actions to the immobility of our bodies; it produces monsters, even though it all seems delicious rather than terrible. In fact, however awful it really is, it’s always undeniably pleasurable. But perhaps it’s the unknown, uncertain, and always changing linkage of this pleasure, this nocturnal kinship of the cinema, that asks a question of both memory and signification; the latter, in the memory of film, remains attached to the experience of this experimental night where something stirs, comes alive, and speaks in front of us. (111).

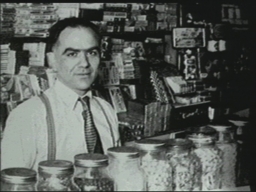

Schefer’s evocative notion of a nocturnal kinship between the cinema and our memories has powerful resonances in the video work of John Conomos. In a number of writings, the radiophonic work Smoke in the Woods, the video Autumn Song and most recently the video installation Album Leaves the cinema is at the centre of a reflection involving personal and cultural displacement, memory and the seductive power of a form of writing based around the electronic image. Each of these texts – especially Autumn Song and Album Leaves – involve a continual returning to images and themes found across the body of work. Taken together, these creative works form a larger memory text dealing with Conomos’ relation to his ancestral home of Kythera; the figure of Uncle Manoli, a poet and misanthrope, whose fate is held up by the family as a grim warning to the artist; the legacy of years spent working alongside his father in a milkbar in the Sydney suburb of Tempe; and the power of cinema to establish a series of relations between the subject and their experience of the world. It may be perverse to refer to these multimedia texts as part of a reflection on cinema, a denial of the hybrid nature of their image form. But I want to propose that the strongest aspect of Conomos’ work over many years concerns its understanding of cinema’s phantasmatic force – its ability to give life to images that “claim us”, images that form our history and take it away. As in Schefer’s written reflections, Conomos’ essayistic video work is informed by the problem of understanding what Paul Smith calls “an atopia of the subject”, a subject dispersed across time and written through by the effects of memory. [7]

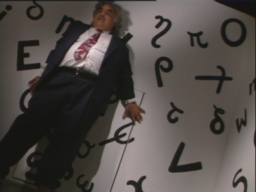

And in Album Leaves, in particular, Conomos positions this temporal displacement of the subject as central to the very form of the image. In other words, he uses video to write an autobiography with images that is both highly theatrical and marked by a constant instability within the very image itself, an image that is always “changing face” much like the subject of the reflection who finds himself caught between cultures, constantly renegotiating a sense of who he is and where he belongs.

In Album Leaves this displacement of both image and subject occurs through a number of different means: sometimes through a morphing of images from Autumn Song, at other times it is through a collage effect, juxtaposing and combining two or more images to form something poetic. But make no mistake, Conomos is not simply a tinkerer, playing with and manipulating images to create a form of cinephilic reverie. He is also a performer, one who places himself in the picture and acts out a particular form of autobiographical dispossession. As Edward Scheer puts it, “He doesn’t so much move into the image . . . as the image moves into him, producing a kind of uncanny displacement of the familiar into the even more familiar”.[8]

The result of this performative drive is to suggest a relation to the cinema in which we inhabit the image and at the same time are inhabited by its lustre and its promise. Here again it is possible to detect a connection with Schefer’s understanding of the mysterious bond between spectator and image in which identification occurs not simply on the basis of character but with the image all over: “It’s with the entirety of that world on screen that the spectator participates or identifies himself, and it’s there that he’s most sensitive to the effects of spatial dislocation, temporal distortion, and especially to emotions”.[9]

Our fascination with certain images, objects or gestures, Schefer adds, is drawn not from a “sovereign consciousness but a disguised body, dressed from the start in a prism of minor passions, sequences of gestures, words, and lighting”. (116)

In films the body (in any situation) is only desirable because of the hope that its clothes can be worn, but at the same time that it can carry away with it all the worldly light in which it has bathed. The initial hallucination in which we mimicked gestures . . . managed to induce, in place of our bodies and like an airy chimera, the same stiffness we saw in the actor, the same pleasure in details; or it managed to teach us that the cinematic body is one that lives “in detail”. . . (116)

In Album Leaves these images and details drawn from the history of cinema and the visual arts have been treated by the artist, souvenired, one might say, and rearranged in a landscape that tries to bridge broader questions of image relation and a personal tale of fathers and sons. In her influential study On Longing, Susan Stewart writes that the souvenir has the effect of “moving history into private time”.[10] In Album Leaves Conomos’ practice of souveniring has precisely this effect of marrying a speculative concern with image culture and the history of cinema with a reverie on his relationships with both his dead father and his own son.

In one particular scene which captures the work’s ambulatory mood of reflection and melancholy Conomos wanders through a graveyard looking for his father’s grave – mumbling to himself as he moves along the row of plots. When he comes to the plot where his father is buried there is both a sense of relief and disappointment – “It’s not what I imagined it to be”. His words trail off, but are picked up at another point in the work. Looking down at his father’s plot, Conomos remarks “It’s so hard to capture him . . . You never do, do you? You just chase your own shadows”. Conomos’ simple but evocative words and actions touch on something very crucial to the fascination drawing us back to cinema: in the projected images passing before us we look for something of ourselves, not an ideal self as we once thought but something unknown and mysterious, something which forms part of our history like a “silent bounty” but which also resists being spoken. In the particular oedipal scenario that works across Album Leaves these images mark a “father hunger” that propels each of our journeys back to the cinema, journeys back to reinaugurate the nocturnal kinship with that part of ourselves lost to time and memory.

For Conomos, then, the cinema not only provides an echo of the subject’s displacement across cultures but also a chance to draw out of this an image that can be held up and scrutinized for its capacity to tells us how we exist in time. In Album Leaves just such an image is drawn from the final moments of Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (France 1959): the now famous conclusion when Antoine escapes from the reformatory where he was incarcerated by his parents. In the closing sequence the film follows Antoine’s flight to a nearby beach where, after running to the water’s edge, he turns and heads back towards the camera. The image then freezes and the camera zooms in on the still image of the boy’s face. When Antoine turns and looks directly into the camera he looks directly at us and, it must be said, also the figure behind the camera whose memories and experiences have passed across to the cinema. Antoine’s gaze marks the autobiographical nature of the tale, its foundation in the director’s own experiences of growing up. And, as a figure of time and memory, his gaze into the camera also suggests the durability of that past – the mark of everything “which does not change in the midst of what we add to ourselves everyday”.[1]

Antoine’s gaze into the camera suggests that these experiences which we look back on only exist in and through an experience of cinema that has ghosted the entire life, an experience of cinema that moves both forward through our lives and projects back, giving shape to our history and spiriting it away. It is this sense of the cinema projecting both forward and back – laying claim to our lives and our history – that is crucial to Conomos’ entrancing reflections on cinema and memory.

Endnotes

[1] Italo Calvino, “A cinema-goer’s autobiography” in The Road to San Giovanni (London: Vintage, 1994) 37-38. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[2] George Toles, “Being well-lost in film,” Raritan 3. 2 (1993): 94-95. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[3]Robert Burgoyne, “Prosthetic memory/traumatic memory: Forrest Gump,” Screening the Past, Issue 6 1999, , (April 1999).

[4] Paul Smith, “Introduction” to Jean Louis Schefer, The Enigmatic Body: Essays on the Arts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), xiii.

[5] Paul Smith, “The unknown center of ourselves: Schefer’s writing on the cinema,” Enclitic 6, no.2 (Fall 1982): 33-34.

[6] Jean Louis Schefer, “Schefer on cinema’, Wide Angle 6, no.4 (1985): 57

[7] Paul Smith, “The unknown center of ourselves”, 34.

[8] Edward Scheer, “Conomos and the anti-uncanny”, Real Time 33 (October-November 1999): 20.

[9]Jean Louis Schefer quoted in Paul Smith, “Our written experience of the cinema: an interview with Jean Louis Schefer, Enclitic 6, no.2 (Fall 1982): 41

[10] Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of he Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, (Duke University Press, Durham,1993), 138.

[11] Jean Louis Schefer, L’ homme ordinaire du cinéma, (Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1980), 61. Quoted in Paul Smith, “The unknown center of ourselves”, 37