Uploaded 9 January 2002

Introduction

Photographs, along with theatre schema, books, trompe l’oeil paintings, and maps have served as memory technologies that draw on visual and spatial systems. These technologies function as repositories for memory, a place where the past is deposited and later retrieved. If as Ada Lovelace envisaged, the computer is in essence a memory technology, multimedia as an imprint of zeros and ones with spatial dimensions is ideally suited to the portrayal of the fluid and multi-layered constructions of the past. Indeed, recent multimedia works have repeatedly used critical practice to rework theoretical debates about memory.

Currently, we are at a preliminary stage of conceptualising the computer screen as an exploratory space with aesthetic dimensions. I would argue that a more focused grasp of the aesthetic dimensions of computer screen space is a vital component in understanding contemporary new media practice. This paper attempts to open up this discussion by exploring debates about technologies of memory and illustrating these issues through reference to a section of my own digital media work: Meander.

Meander is a multimedia work in progress [1] that draws strategies from both the autobiographical and documentary areas of media practice to establish a conversation between actuality (domestic photographs, 8mm home movies) and the personal (recalled memories). These aspects are foregrounded in relation to feminist discourses about memory and subjectivity and digitally constructed into memory scenes. In these scenes, I attempt to integrate ideas about photography as a medium of memory into the techniques of collage as a strategy for the visualisation of a subjectively positioned past. In so doing, I contest ideas about digital media as mere surface spectacle and facile pastiche and instead argue that new media enable a productive interplay between conceptual ideas and visualising techniques in the spatial dimension.

In using my own work, the paper investigates how questions about re-constructing the past might be articulated through multimedia design – specifically conceptual design and screen imaging. The key questions I am exploring are: what is the act of memory; how have photographs functioned as domestic media of memory, and how might these ideas be incorporated into a multimedia screen design? In answering these questions, I attempt to theorise how domestic photography and film function as media of memory within a particular form of media arts practice.

Acts of Memory

Whatever the reason may be, I find that scene making is my natural way of marking the past. Always a scene has arranged itself: representative, enduring(Woolf,142).

In a series of memoirs written in 1939, Virginia Woolf recalls her first memories: the colours of her mother’s dress close up on a journey; hearing the waves breaking; the blind being drawn at St. Ives and feeling “the purest ecstasy I can conceive” [2] . For Woolf, the past was divided into moments of being and non-being. Moments of being were life lived consciously as rapture, compared to non-being, the cotton wool everyday type of existence. These descriptions of heightened experience relate to what James Joyce would have called an “epiphany”. The most famous literary example of this accelerated moment of recollection must be Marcel Proust’s ecstatic moment in A la recherché du temps perdu, where a flood of involuntary childhood memories are activated upon eating a Madeleine. These recollections understood as “a token of some real thing behind appearances” (Woolf,84), suggest involuntary memory as a key to an unproblematic version of the past. This notion of memory as a direct link to an essential truth echoes the Greek understanding of mnemonics as a conduit to transcendental knowledge.

For the Greeks, memory was mnaomai – to mention something or somebody. The Greeks devised mnemotechnics as a strategy of recall where information would be visually mapped onto a real or imagined space. In The Art of Memory, Frances Yates describes how students of rhetoric would mentally map the elements of the speech onto the geographic space of a building in order to memorise it. In re-constructing the speech they visualised walking through the imagined building, accessing the room structures and their associated elements of knowledge. During the Renaissance there were hopes that this memory system with its emphasis on cognitive knowledge and the occult would become a universal language based on spatial, visual systems. Thus, within the rules of the mnemotechne, space both real and imaginary was perceived as a technology of memory.

Amongst the most important Renaissance practitioners of this form of the art of memory were Giulio Camillo and Giordano Bruno. For them this technology of memory was seen as the key to essential truths and transcendent knowledge. Giordano Bruno devised memory images out of a history of human observation, shapes, forms and colour and the rotation of heavenly bodies. Giulio Camillo built what he called a memory theatre, an amphitheater where all the memory of the world was inscribed through a variety of little boxes, niches, images, figures and ornaments. In this memory theatre, iconic artefacts located within the architectural landscape set up an indexical relation between the object and its mnemonic element. As a system of recall, these memory systems start to look very contemporary in light of computer technologies and particularly multimedia with its reliance on visual systems, spatial analogies and trompe l’oeil style representation.

Simon Sharma in Landscape and Memory has another take on memory, memory as a projection onto the places and sites of the landscape. He argues that the garden of Western landscape has been conceptualised as a view framed through the cultural habits of humanity. Through these frames, geographical locales have become overlaid with mythology and the human imagination to become embodied memory. One example he provides is the mediation between geography, invention and culture in the German woods of the late 18th and early 19th century. In this mediation the woods are represented as Druid groves, woodland idylls and sylvan Arcadias to create an idea of a utopian primitivism directly link to a notion of the German character.

Pierre Nora, also conceives of memory as a site or place, as a Lieux de memoire. In Realms of Memory, he argues that Lieux de memoire have arisen as a replacement for the lived experience of memory within a community, the milieu de memoire. For Nora, modern memory is first of all archival. “It relies entirely on the specificity of the trace, the materiality of the vestige, the concreteness of the recording, the visibility of the image” [3] . He argues that the less memory is experienced from within, the more we rely on external props, in particular the archive and documents of authentication. Nora goes on to say that in the process of not knowing what might be precious in the future, we have lost the art of selectively forgetting, resulting in the increasing burden of mass accumulation of evidence of the past.

In collecting evidence of the past, the computer has become the primary vehicle for storage and retrieval. If the computer then houses the memory theatre, what are the forms of imaging and how do we conceive of the past when multimedia (as the computer’s specific memory technology) allows for and expects an active interplay between user and screen?

Media Arts.

Within media arts, the computer screen offers us a digital mise-en- scène, which references theatre, pictorial traditions and cinematic conventions. Over the last decade, multimedia has emerged as a key device for manipulating these media conventions. My own work Meander draws on the digital techniques of compositing and multilayering to construct scenes as a way of marking the past. Using photographs as the point of departure, it contrasts divergent family narratives through audio-visual re-constructions of recalled moments from the past. Memory fragments in the form of visual tableaus are animated though archival 8mm film, family photographs, soundscapes and recently filmed landscapes and objects. These tableaux seek to articulate moments of epiphany – moments of recollection and revelation that have become embedded in the memory against the background of family fictions.

The past buried in the imagination and refracted through the families media of memory, (photographs and home-movies) is evoked through the archaeological investigations of the author as adult. Viewed from a distance, the domestic and everyday starts to look like the spectacular other – the exotic, aligned to an anthropological study within which there is no fully ‘outside’ position. In the process of observing the past, issues of family dysfunction, the split between the experiential self, the familial other self and the child remembered self are bought into sharp focus. In illuminating the past as personal ethnography [4] , Meander plays with identity positions, questions of power relations and re-arranges family hierarchies. In it authorial subjectivity is on display and held up to scrutiny through the navigable pathways through familial mythologies of memory.

Meander draws on personal ethnography to navigate the territory of memory through the media of authentication (photographs and 8mm home movies) and personal remembering. Whilst archival footage and the documentary interview hold a privileged position in relation to notions of the truth and claims to the real, Meander explores the construction of memory as leaky. By taking photographic albums as a tool of aide memoire, divergent modes of recall and multiple subject positions are taken up by the family. In these positions and resulting filmed narratives, the archival photographs both construct an absence – by referring to that which is no longer present – and construct a mythology of the author’s own subjectivity based on fragments of memory.

The author’s own childhood memory fragments mix the found and the fictional to form audio-visual scenes as sites of exploration. These scenes are constructed through sense memory: words; smells; sounds; visions. Rooms in an Edwardian house in Northern England; old photographic slides in a hand-held projector; eating liquorice on the back seat of the car; a nanny sitting on her hair in a red room; Mr. Snow played on a piano; the texture of fur against skin; the sounds of the garden in the early morning.

The playroom in the house constructed from childhood memory fragments.

A long cherished dream of humanity was the power to fix the reflections of the mirror and make pictures without the aid of the artist’s pencil [5]

When the image from the camera obscura was first fixed onto a pewter plate in the 1820s the process was seen as both scientific and magical. In its association with positivism [6] , the camera was established as a direct recorder of observable facts and reality – a scientific instrument for recording an impersonal and objective neutrality. Simultaneously, the chemical process of fixing the sun’s rays was seen as alchemic and magical. For Fox Talbot, the inventor of an improved version of the photogenic drawing, the Calotype, photography was an aid to memory, a means of easing the burden of ever-accumulating information and sense impressions. For Talbot, photography, as an attempt to retain the past, was the new technology of memory for drawing nature, ‘the pencil of nature’. [7]

In Camera lucida, Raymond Barthes argues that the legitimate antecedents of photography were chemical transformations rather than the camera obscura and perspective. It is indeed easy to imagine that the process of an image appearing and being made permanent would have held a fascination at least equal to that described on viewing the Lumiére brothers’ film: The arrival of a train at La Ciotat station some sixty years later. Photography thus conceived by Barthes as an “emanation of past reality: a magic, not an art”[8] takes its place within a history of 19th century spectacle and illusionism along with the diorama, magic lantern and phantasmagoria. These devices draw attention to temporality, to the space between the still images, the interrupted sequence of a new slide or a change of lighting. The focus rests with the creation of a spectacular mise-en-scène based on curiosity and fascination, rather than with the perspectival illusions of the new optical devices.

Over the next forty years, the emerging phenomenon of photography took another twist into domestic consumption through the family portrait and the carte de visite. These visual wonders allowed a personal image to be preserved and carried around for the first time. Becoming the rage by the 1860s, the carte de visite or carte portraits were sent to friends and collected in albums. By 1888 Kodak set up the family as amateur photographer by introducing the box camera with pre-loaded and roll film. Since then the family photograph as domestic snapshot, as captured magic moment, has become intrinsically bound up with memory production, domestic pleasures and family viewing.

Slide of the house and garden, 1963.

Through the development of the snapshot, the family’s past becomes framed for the future through the dominant discourse of family relations as safe and enduring. For my father returning from a war that he refused to speak about, photographs erased the past, monumentalised and stabilised the family for the future. “I was just taking pictures thinking this would be good to look back on in later years when I’m old and grey and the children are grown up and we can look back and say these were happy days” [9] . Family photographs chronicle the passage of time, signify rites of passage (christening, communion, and first day at school, birthdays etc) and construct middle class narratives of status and success. This process takes place primarily in four stages: the construction of the family through the devices of lens; framing and composition at the time of taking the image; the organisation of the photographs into a context for viewing; and finally the re-working of the images and act of reviewing in the present. In producing, organizing and re-looking at the images of the past, the photograph as a medium of memory is subject to multiple meanings, specific fantasies, subject to present situations and the acts of remembering and forgetting. As Annette Kuhn says “the past is made in the present” [10] and the past becomes a contested zone with each reviewing and family narration.

These single moments captured by the click of the shutter remain isolated. As separate moments they have no center, they occupy empty space. They require a narrative to re-construct them. As Susan Sontag argues; “only that which narrates can make us understand”(Sontag, 23). Since the 19th century, the primary vehicle for constructing these freestanding particles into narratives or stories of collective family memory has been the family album. The process of editing images into icons undertaken through the ordering, composition and accompanying text of the family album constitutes a story of domestic lives from which images of conflicts, difficulties and labor are erased. During it, images undergo inclusion, exclusion and various framings. What types of narrative are constructed through this process?

For my family the photograph albums have been the battleground for control of a family narrative. First my father’s chronological organisation of “happy moments” with white pen identification of place, location and name in leather bound albums. Then my mother, who in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease cropped each photograph to simulate photo corners and arranged them without accompanying words or linear chronology. More recently, my own retrieval and removal of photographs from the album, some still with the glue residue and torn backing paper into a Tesco’s plastic bag. The removal from the album forms the preparatory stage for another construction through photomontages and animation. What are the meanings of these different editing processes? Was my father’s aim to make the snapshot a point of stability in turbulence? My mother’s to make sense of her past and tell her story as a person losing her memory? Mine to construct a context that I can inhabit?

The construction of a photo album offers a fractional story with different narrators, many authors and based on the expectation of future generations of readers. It is structured from a series of past unrelated moments, stories and anecdotes into a fragmented narrative. Such narratives function like hypermedia texts with disjunctions, leaps from one event to another, dead ends and little sense of closure. Within the book of the family, what is left out often becomes more significant than what is immediately visible – the excluded photographs, the traces of the on-going narrative outside the moment captured and the off-screen visuals beyond the edge of the frame. For in looking at the albums there is the shock of non-recognition, the contradiction between the memory and the image. The photographs become, as Barthes has pointed out, “both a pseudo-presence and a token of absence” [11] . The photograph ultimately points to loss rather than reminding us of presence. It “does not necessarily say what is no longer, but only and for certain what has been” (85). This “certificate of presence”, the authenticated image provides a code, a direct encounter with the maker of the image in direct opposition to the experience of involuntary memory.

Various cultures have taboos against this certificate of presence; either at the point of the photograph being taken or in viewing the photograph after the subject has died. For even at the time of its inception, the photograph, as an image from the past anticipates death. In so doing, it can effectively function as the opposite of memory as an erasure of memory. As Barthes argues: “not only is the photograph never, in essence, a memory…but it actually blocks memory, quickly becomes a counter memory”(91). My sister recounts how photographic media have become her memory: “If I didn’t have photographs, I don’t know what I’d remember. My memories are cinefilm and photographs. They’ve gone into my mind.”

As simulacra of memory, family photographs with their albums and mantelpiece frames claim the space of history. The past becomes reflected within domestic photography as the holder of memory. My father, the director of the family’s photographic archive describes the photographs as memory: “I wanted to preserve the memories because the memories fade quickly and it’s nice to have them on record”. The photographs form the lieux de memoire of the family, enshrined within ideas of leisure and the artefacts of middle class consumerism: the house, the caravan, the beach holiday and the motor car.

My attempt has been to set up questions of memory, to situate photographs as material for interpretation and evidence – to concur or disprove personal reminiscences. For what is remembered of the self when the observed is there as masked performance? In the face of the shock, the discord, we can’t recall looking like that, being in that place, but the photo shows we were there, Barthes “That has been“(77). Photographic images function as a trace, as a code or clue to a meaning that is located elsewhere “like a riddle read and decoded”(Kuhn,18). The process involves a search for a self that has been erased through the photograph and more emphatically through the construction of the album. It is an attempt to reconstitute an absent self in defense of what is invisible, what has been hidden by the masked performance.

My father’s album image: Manchester, 1969

Jo Spence has taken up this theme of masked performance in a series of phototherapy works inquiring into positions of subjectivity behind the photo album. With Rosy Martin she explores the mother-daughter dyad in self as mother, self as cleaning woman, late mother. Other examples draw on photo documentary techniques in order to mimic the tropes of the domestic and studio portraiture, such as, self as Hollywood virgin bride. The documentary images of self as medical victim in the drama of infantilization explore “where fact and fiction, past, present and future intermingle in the timelessness of dreams and memories” [1] .

Cindy Sherman, like Jo Spence, sets herself up as the subject performing within the frame. Sherman’s work draws on the fictions of cinema to explore and reverse Laura Mulvey’s notion of the gaze. In working with the codified styles of ‘B’ movies and late ’50s and ’60s film noir, the femme fatale image becomes the body posing as subject for itself. Apparently exposed for the male gaze, Sherman’s self-portraits invoke the syndromes of exhibitionism and voyeurism whilst simultaneously constructing their own image as speaking voice. By scrutinising subjectivity itself and reversing the tropes of cinematic female positioning the body is invested with autonomy. Both Sherman and Spence counter photography as bodily intrusion by turning it into a mirror-mask to reflect back conventional bodily gestures of the female subject and expose dominant visual conventions of photographic stills.

This reflection and exaggeration of photographic visual conventions is a key element in underscoring the recorder/subject dichotomy inherent in the family snapshot. In moving the image past its domestic site and to draw attention to the subjective, Meander further develops the idea of the mirror-mask through an interplay between the self as imaged in the original photograph, the ‘tangible object’ and the re-worked scene. These forms of representation take place within a history of collage with the photograph looking back to its status as a physical object and forward to its position as the photo-graphic.

Electrobricolage

Photographs as physical objects offer a slice of the frozen past. As objects of memory they can be kept, re-framed, organized and developed into a series of narratives through the photo album, the slide show with voice over narration, or made sacred within the shrine on the mantelpiece or the piano. As analogue objects they are effected by time – they can rip, yellow, be lost, torn and eventually thrown out. Our understanding of photographs is shaped through their impermanence, their placement and location within the domestic setting. How do these meanings change when they become part of digital media?

I would argue that the surfeit of digital images and the speed at which we receive them increases the potency of the paper-based photograph as an icon of nostalgia. The original photograph can be scanned, digitally simulated, viewed on screen, sent as an email attachment or uploaded into a family web site. In so doing, it becomes screen based, a digital trace of zeros and ones. As a less fragile memory trace of its analogue image, it is highly suited for the archive, but less precious as a link to the past losing some of its original symbolic or mythological power. As Nora notes “the trace negates the sacred but retains its aura”(Nora,9). In retaining its aura, the digital media refers back to the original photograph which itself is a reflection of the original moment captured. This dilution of the past initiates a rupture of the narrative of cozy domesticity from which it came.

Extending this rupture, the photographic trace in digital form reworks the privileged text through the process of montage. Readily available tools on the desktop computer enable multiple perspectives, reorganizations and interpretations simultaneously. William Mitchell, in his analysis of post-photographic forms of representation calls this process electrobricolage. The ability to endlessly manipulate, layer, re-size and colourise the scanned photograph poses a disruption of the integrity or authenticity of the photograph. Two uses of this technique that spring to mind are the collages of Hannah Hock and Tracey Moffatt. As a Dadaist in a pre-computer era, Hock used disruptive montages of dominant iconic representations. In re-working the controlling narratives of popular culture, Hock worked with the cut up, juxtaposition, multi-layering and text to make ideological statements of resistance. Moffatt’s large-scale cibachromes in the Something More series also employ collage to offer a critique of unified anthropological constructions of culture and gender. In these, characters as isolated spheres are imposed into the landscape with an eerie spatiality. The cut and paste look and multi-layering techniques evoke the messiness of memories – intense moments of recollection set against a background of emptiness. This translation of memory traces and atmospheres into scenes operates in ways that suggest childhood memories as described by Woolf. “Many bright colours; many distinct sounds; some human beings, caricatures; comic; several violent moments of being, always including a circle of the scene which they cut out: and all surrounded by a vast space” (Woolf, 92).

Morphology of Memory

Through the digital apparatus of the computer and its multimedia software new forms of digital visualisation emerge that extend far beyond the visible realms available to camera lens technologies. The creations of multimedia screens are thus more closely aligned to the chemical transformations of photography rather than any lens based apparatus, magic rather than scientific observation or the purely documentary. In Meander, these curiosities are used to resurrect personal recollection from the purely testimonial “That has been” to produce a tableau of multiple subjectivities. In making the scenes, I piece together formerly disconnected pieces of material from the family albums,8 mm home movies footage, with graphic re-constructions, soundscapes recorded at the location and recent video interviews. In the reconstructions, I place myself in the foreground and create another story in the background unsettling any unified family narrative. The composition draws on traditional genres of photography – the single portrait, the group shot, and holiday photographs. These are set within the extended landscape of such tropes as the beach scene, the perfect summer’s day, the first day at school, the first communion.

The primary site for these collective nostalgias becomes the home as often the main acquisition of the family and the location of family interactions and togetherness. In and out of it, the architectural fabric, the surrounding garden, the rooms and objects become overlaid with symbolic association. The house functions as a type of cabinet of curiosities, with its collection of objects, souvenirs from another world and recalled artefacts of childhood.

Main menu screen Meander – the house of many windows.

The house of many windows functions as the main menu offering navigable pathways through the family’s deviating forms of recall and constructions of the past across the key sites of house interior, the church, the school, the beach holiday, and the garden. An Edwardian house leads the way to scenes in the kitchen, the bedroom, the attic and the playroom where we hear the contesting stories of the brother, the sister, the father and the nanny. My brother describes his memories of “different levels, different things happened on different levels, great fun, great home”. My sister recalls “which room is which. . . . the furniture, decorations, things that went on in various rooms”, whilst my father recalls his areas of responsibilities, the car, the fencing, the lawn. The nanny recalls the house: “quite awe inspiring, huge, suddenly appeared at the end of this drive, quite magnificent. I remember seeing it for the first time walking up to the front door – beautiful yellow bricks, that was lovely, then going inside”. These differences point to the varied power relations within the family and the way that personal memory is used to reinforce or contest these positions.

In the interviews, family members are asked to describe their memories on seeing the photographs and to consider the construction of their own recollection in relation to the photographic images. The family’s responses shot on video use the talking head technique of documentary and form a moving element of the composited screen tableau. The family reflects on memories after looking at photographs from the past, offering divergent narratives constructing what might be called mythologies of remembering.

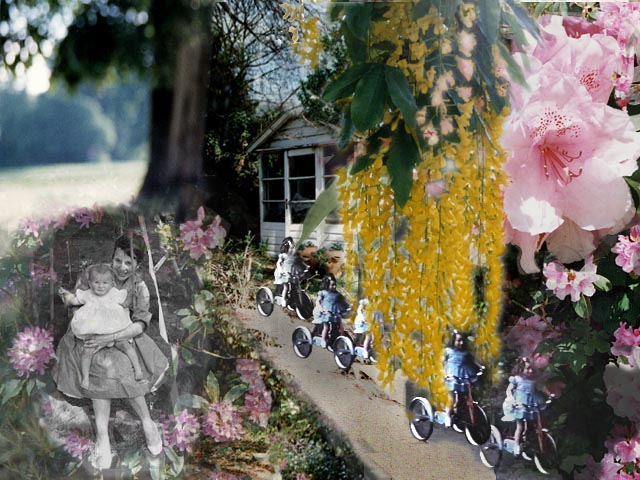

My father, as the photographer of the family, used the garden as a primary site for embodying memory within a type of English middle class romantic landscape. In the interviews my father talks about the landscape of the garden identifying species: sycamore, laburnum, hollyhock, red roses, ivy, mint that went wild, rhododendron, green lawn, and the beech hedge. In the original photographs of the garden shot by my father, these plants along with the children as the less wild creatures form part of the tamed, domesticated outdoors separated from nature beyond the gate. In the reconstructions I put myself back in the picture as both the portrait mask self and as author of the reconstructed tableau in order to de-stabilise memory as a singular transparent truth and to question how photographs have functioned as domestic technologies of memory.

Video sequences form a distinctive component of the Meander scenes. They are used to represent the images that replay and take precedence in the memory – journeying to the beach, lying in the grass, listening to my father playing the piano. These insistent memories are composited in After Effects by animating elements of the photograph with recently shot video footage. They play as short moving video loops against the still photomontage backgrounds in a tradition that returns us to the pre-cinematic linear forms of the Kinetescope and other looped 19th century illusionist devices. This context locates the visual images of the past as medium of memory, not as authenticating documents but as images of magic, spectacle and the imagination.

Objects as artefacts – the commonplace objects recalled, but no longer in the photograph – are re-inserted into the mise-en- scène. These take on a particular significance as repeating involuntary memories; more important perhaps because they don’t feature in the original photographs – the bubble bottomed glass on a lace tablecloth, a picture of Christ, a particular beach towel, the texture of a fur coat. This strategy draws on Barthes’ idea of punctum – the small marks that paradoxically fill the whole picture – a refraction of Joyce’s notion of epiphany in visual form. For the user navigating the multimedia landscape, moments of realisation are archaeological findings, used for investigating, re-interpreting and constructing a story. In a process akin to digging and shifting through an archaeological site with a teaspoon, these missing objects of significance become clues to missing elements of a fragmented narrative.

Techniques from the documentary or ethnographic film – forms of legitimating evidence, such as original photographs, oral reminiscences, film footage and interviews – collide with the collage techniques. On screen, the physical existence of the photograph on the top layer is emphasised, coding it as tangible object and lending it the status of familial memory against the visual depth of the composited scenes. Through this strategy, the rhetorical and aesthetic tension between ideas of real memory and their referents in the family archive – the medium of memory are never fully resolved. Indeed are set out as points of tension or collision within the work. This illustrates the cross over between documentary’s link to actuality and the relationship of pictorial convention to the subjective and imaginary.

Garden collage as memory sequence

The collages deliberately reveal the process of recombination and juxtaposition, the joins, oddities of scale and lack of perspective between objects. In the collages (“collage” is from the French Coller– to stack) images are stacked in layers, overlapped and combined with techniques from pictorial illusionism. This exaggerates the disjunction between the flat plane of the original photograph against the two dimensional picture space – the foreground and background planes of the composited scenes. In using pictorial conventions and techniques that refer back to the screen language of bricolage, photography and the home movie, Meander reveals the continuously variable relationship between the original and the re-worked images, the historical and the subjective.

As a navigable space the user enters a negotiation with the souvenirs of the past. Movement in screen spaces is translated into hyper-leaps between one scene and the next through the motifs of doors, objects, passageways, windows and the photographs themselves. The architectural spaces of memory are navigated by selecting narrative fragments or locations to track. The user can follow a pathway based on a perception of recall or construct hyper-linked connections between photographs by arranging their own album. Meander effectively translates the family memory into the spatial domain through the stacking of planes of memory; the collages of family narratives and constructed scenes of recall. In so doing, Meander becomes a space of memory recalling the artefacts, icons and figures of the memory theatre. This traversing exceeds the bounds of the merely self-reflexive through the universality of the domestic elements – the spaces of a middle class English childhood – the house, the school, the garden and the church. In it the user is engaged in a process of exploration about the ways that photography functions as a medium of memory providing a new understanding of relationships between self identity and the process of familial memory creation.

Conclusion – Meander as Memory Space.

If the early hope for photography was to fix the reflections of the mirror, it is a distorting, clouded mirror that brings along with it dreams, perceptions, fantasies. Rather than being a precision instrument, it is one that disrupts and disturbs recollection as much as it embodies or makes the past. In the act of remembering, mnaomai, of mentioning something or somebody, photography as a memory media proclaims absence as much as presence, illusion as much as truth.

As analog photographs erode as icons of family history and own memories diminish, we rely more on our technologies of memory. Meander as an autobiographical technology of memory starts out with a sense of loss, to seek nostalgically for traces of memory in family photographs. At the heart of these photographs is ultimately absence, absence of the past, absence of a singular autobiography or unified family story. This final absence speaks about the limitation of the family photograph as a medium of memory, its failure to restore what has gone – the past. In response to this absence, Meander appropriates the genres of family photography in order to expose their fiction and how these fictions create audience memory. The intent is to dismantle the family album in order to reconstruct the memoirs into ‘moments of being’ through the media of photographs, home movies and family recollections. These memory fragments, re-incorporated into a tableau restore the scene as a space of the past. What is created in the place of a tidy testimonial are the rituals of memory and the construction of a personal mythology. In so doing, another memory space is established – one that is deliberately reflective and self-conscious about its process.

Like the memory theatre of Giulio Camillo Delmino, described in Francis Yates’ Art of Memory, the user can navigate the landscape of memory embedded with riddles and clues. In the process, the interplay between imagination, memory and the autobiographical is mapped into the path of user navigation. In this way, the user is engaged in a process of memory creation and a debate about ways that photography functions as a medium of memory and the work itself becomes a memory space.

Selected bibliography

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (London: Flamingo, 1984).

Jane M. Gaines, and Michael Renov, eds. Collecting Visible Evidence, Visible evidence, Volume 6 (Minneapolis. University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

Martin Lister, ed. The Photographic Image in Digital Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1995).

Peter Lunenfeld, ed. The Digital Dialectic, New Essays on New Media (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1999).

William J. Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye, Visual Truth in the Post-photographic Era (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1992).

Pierre Nora, Realms of Memory, The Construction of the French Past (Columbia University Press: New York, 1996).

Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (UK: Harper Collins, 1995).

Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977).

Jo Spence, and Patricia Holland, eds. Family Snaps: The Meaning of Domestic Photography (London: Virago, 1991).

Jo Spence. Putting Myself in the Picture, a Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography (London: Camden Press, 1986).

Virginia Woolfe, Moments of Being. (Herts, England: Panther, 1976).

Francis Yates, The Art of Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966).

Endnotes

[1] Meander is at the conceptual design stage with some indicative visual media and prototype design.

[2] Virginia Woolf, “A Sketch of the Past” in Moments of Being. (Herts, England: Panther, 1976),75. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[3]Pierre Nora, Realms of Memory, the Construction of the French Past. (Columbia University Press: New York, 1996), 8.

[4] Personal ethnography is Michael Renov’s term for a particular sub genre category of documentary.

[5] Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, A Concise History of Photography. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971), back cover.

[6]John Berger makes the point that positivism and the camera developed in parrallel. Auguste Comte was writing Cours de philosophie positive at the same time of the development of the camera.

[7] The Pencil of Nature is the name Fox Talbot used for the first photographically illustrated book published in 1844.

[8] Roland Barthes, Camera lucida. (London: Flamingo, 1984), 88. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[9] Video interviews with family members by the author, 1997

[10] Annette Kuhn, ‘”Remembrance” in Family snaps: the meaning of domestic photography’in Family Snaps: The Meaning of Domestic Photography, eds. Jo Spence and Patricia Holland (London: Virago, 1991), 22

[11] Susan Sontag, On Photography. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 16

[12] Jo Spence, “Soap, Family album work…and hope” in Family Snaps: The Meaning of Domestic Photography, eds. Jo Spence and Patricia Holland. (London: Virago, 1991), 207