Uploaded 1 December 2001

A male director’s relationship with his actress is almost always imbued with myth. Kenji Mizoguchi’s (1898-1956) collaboration with Kinuyo Tanaka (1909-1977) is no exception. Stories revolving around the private life of their romantic relationship tend to fall into cliché, crediting Mizoguchi with Tanaka’s “rebirth” as a great actress with The Life of Oharu(Saikaku ichidai onna, Japan 1952). Tanaka’s single-minded, passionate devotion to her occupation is often compared to Mizoguchi’s almost sadistic attitudes toward actors and the eccentricity of his perfectionist approach to filmmaking. Thus, romantic rumours are sublimated into Romantic myth.

It might be tempting to look at artists in Mizoguchi films as Mizoguchi substitutes – characters such as Hogetsu Shimamura (So Yamamura), the theater director in The Love of Sumako the Actress (Joyu Sumako no koi, Japan 1947); or Utamaro (Minosuke Bando) in Utamaro and his Five Women (Utamaro o meguru gonin no onna, Japan 1946). We might then superimpose their romantic and aesthetic relations to such characters as, for example, Sumako the actress or Okita the model onto the “real life” story of Mizoguchi and Tanaka. In spite of many anecdotes which address this off-screen life, however, Tanaka’s on-screen acting is rarely discussed. Do we really know Tanaka and Mizoguchi? The most fascinating aspect of the penultimate scene of The Life of Oharu is the way in which Tanaka scurries through the palace, chasing after her son. How can we account for the fascination generated by her steps?

Another common presupposition is that Mizoguchi took on the role of transformer while Tanaka played the transformed. But isn’t the reverse possible? Tanaka plays the heroine in as many as fourteen of Mizoguchi’s films. [2] Isn’t it reductive to frame the long career of an accomplished actress as a matter of her merely being the docile object of Mizoguchi the Pygmalion? Tanaka made her film debut at the Shochiku studio in 1924 and soon became a star. Her critically acclaimed performance as a young married woman in Heinosuke Gosho’s The Neighbor’s Wife and Mine (Madamu to nyobo, Japan 1931) not only secured her popularity as a talkie actress (contrary to the studio’s worries about her accent), but also symbolically inaugurated the standardisation of sound in the Japanese cinema. It is true that throughout the late 1940s, as Tanaka herself entered her late thirties, she had to struggle to outgrow her old star image as the “eternal girl” (mannen musume), and that Mizoguchi films from this period, by casting her in challenging roles, might have provided her with the chance for a breakthrough. But the fact is that Tanaka had been recognised as a talented actress long before meeting Mizoguchi, and was an independent woman who, after her visit to Hollywood in 1949, left Shochiku to work freelance, providing her with the leverage to choose her directors and the films. [3]

I would like, however, to transpose the issue from a question of who influenced whom – which seems to me in any case extremely difficult to substantiate – to an interpretive hypothesis based on a reading of the film texts themselves. I argue that some properties of Tanaka’s acting effect, or interact with, Mizoguchi’s style. The period of their extensive collaboration, from 1944 to 1954, occurs during a phase of Mizoguchi’s own stylistic transformation. A certain rupture, or rather a gradual shift, in the use of camera movement in relation to depth of field and actors’ movement has been observed in Mizoguchi’s postwar films. His systematic manipulation of off-screen space for its own sake and use of depth of field and plan-séquence, the sum of which dominates actors’ movements, culminate in the late 1930s films such as The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums(Zangiku monogatari, Japan 1939) and The Loyal Forty Seven Ronin (Genroku chushingura, Japan 1941). Later, the strict use of these formal properties gradually diminishes and leads to more subtle camera gestures of the camera in the ’50s.

My goal in this paper is to analyse Tanaka’s acting in relation to Mizoguchi’smise en scène. Hence, my subject is not Tanaka the actress in general, but Tanaka as she appears in these particular films. In Section 1, I will examine critical discourses about Mizoguchi’s transformation, and factors which may have contributed to the change of his film style. In Section 2, I posit the register of power relations as the framework for my analysis of Tanaka’s acting and Mizoguchi’s mise en scène. My intention is not to discuss the general field of representation of women in Mizoguchi’s films, but to consider how his films and her acting manifestly come into shape as multiple power relations visible on the screen. Sections 3 to 6 will be devoted to analyses of films. There I will confine my discussion to Tanaka’s acting in three films: The Love of Sumako the Actress, Miss Oyu and The Life of Oharu. The seduction of Kudo (Eitaro Shindo) by Omocha (Isuzu Yamada) in Sisters of Gion (Gion no shimai, Japan 1936) is also considered in order to define “prewar Mizoguchi”.

1. Depth of Field and Lateral Movement

It seems clear that Mizoguchi’s films underwent a change at a certain point in his postwar career. Even a casual Mizoguchi watcher might notice changes in a number of aspects. Beginning with The Life of Oharu, Mizoguchi tended to draw his subjects from a world of Japanese tradition, and many of his films, whose settings are placed in the pre-modern eras, fall into the category of the period film (jidaigeki). This can be accounted for not only by Mizoguchi’s inherent preferences, but also by his self-Orientalising gestures, as it were, and aspirations for recognition in the West. It was particularly fortunate that his inclination for “Japanese” subjects coincided with the major Japanese studio Daiei’s ambition to develop overseas markets.

Moreover, from a thematic perspective, Tadao Sato’s remark on women in Mizoguchi films sums up the general critical “impression”:

Then, perhaps, what Mizoguchi was finally led to pursue is a phase where a woman, who became a saint after having undergone distress, forgives a man by forgetting their past. It seems that the state of euphoria of being forgiven by women, for which the late Mizoguchi seems to have sought, is revealed in several motifs: the religious image at the end of The Life of Oharu; the wife who, transforming herself into a ghost, welcomes her husband and son in Ugetsu; the blind mother who strongly holds her son close in the last scene of Sansho the bailiff; the smiling heroine heading to the scaffold with her lover in The Crucified Lovers (Chikamatsu monogtari, Japan 1954). [4]

Even though a woman’s devotion to her lover/husband/father/brother is clearly the main theme consistent throughout his entire career, the sublimation of women’s love to more spiritual, religious transcendence notably colours many of the ’50s films. What Audie Bock describes as “a spiritual power to transcend their physical suffering” resonates with Sato’s comment. [5] In the later years of his life Mizoguchi’s belief in Buddhism deepened, and he might have consciously or unconsciously tried to redeem his real-life abuse of women in his films. Moreover, irrespective of such biographical stories, this reading is undoubtedly relevant, if we watch Mizoguchi’s films at the level of the messages he intended to express. I will not, however, delve into the “transcendent” or “spiritual” Mizoguchi here.This is because, firstly, in the three modern dramas (gendaigeki) made after Oharu, i.e., A Geisha aka Gion Festival Music (Gion bayashi, Japan 1953), A Woman of Rumour and Street of Shame (Akasen chitai, Japan 1956), women’s transcendence over earthly social relations is ambiguous or almost non-existent. Second, and more significantly, because I believe that in order to reread Mizoguchi films as possible social criticism it is necessary to bracket off the unambiguous messages Mizoguchi and screenwriter Yoshikata Yoda manifestly convey, messages which can be easily criticised from today’s point of view as a clumsy disguise of patriarchy. As I will elaborate later, what could solicit feminist readings of Mizoguchi films resides not in their transparent messages like “awaken women’s liberation from feudal fetters” (The Victory of Women, My Love has been Burning and Sumako), or the “eulogy of modern romantic love free from feudal society” (The Crucified Lovers), but in opaque signs disseminated in multiple layers of the texts.

Finally, and most importantly, Mizoguchi’s film language underwent a significant transformation. Here, I would like to emphasise two cinematographers [6] who were, in my view, instrumental in the transformation of Mizoguchi’s style: Minoru (Shigeto) Miki in the ’30s and Kazuo Miyagawa in the ’50s. It should be noted, however, that it is extremely difficult, and perhaps misleading, to try to detect the “author” of this or that aesthetic aspect of a shot or sequence. On one hand, the cinematographers tried to follow the Mizoguchian aesthetic which the director had created in his previous films. [7] On the other hand, it is well known that while shooting Mizoguchi never looked through the viewfinder, and placed his entire trust in the cinematographer. Therefore, what I attempt to do is not dig out an “author”, but rather introduce the cinematographer as an analytical frame to define one period of Mizoguchi mise en scène, as I do with Tanaka.

Miyagawa, who photographed most of Mizoguchi’s films made in the ’50s at the Daiei Studio, [8] seems to have consciously contributed to, or played a crucial role in, the transformation of the director’s style. He recalls: “When Mizoguchi lost his enthusiasm for depth of field, he started telling stories ‘laterally,’ with the help of pans or traveling shots. You know, in Japan, there are stories drawn on scrolls which unfold horizontally. Mizoguchi tried to find an equivalent to these, first in the screenplay, and then in the camera work.” [9] Miyagawa’s words testify to Mizoguchi’s shift from the depth of field to lateral traveling.

Furthermore, his emphasis on the suppleness and smoothness of camera movements and his reference to the painted hand-scroll coincide with Noël Burch’s arguments – albeit ironically. Burch, though appreciating the sophistication and grace of Mizoguchi’s 1950s films, dismisses their camera movements as “the long take à la Wyler”. Yet Burch does not simply condemn the loss of the early Mizoguchi’s rigour and systematic application of long takes and the depth of field.; rather, he deprecates the seamless (i.e., “Western”) property of the late Mizoguchi’s découpage:

In particular, one observes in this film [The Life of Oharu] and in the others of the 1950s such an utter absorption in the aesthetics of the long take, its organisation and composition, that it is as if shot-changes simply did not exist. Each cut gives the same impression of perfunctorily ‘turning a page’, as in, say, Visconti’s Il gattopardo [Italy 1963]. When the end of a shot has arrived, we pass on to the next, and the spatio-temporal event constituted by that change seems to be regarded as non-existent, whereas even in Tale of Late Chrysanthemums [Japan 1939], where cuts were rare and were not the object of any special effort, they were almost always produced as caesura. The camera in these later films was, of course, as supple and free-moving as it had ever been before, but totally subservient to a stylised version of the dominant code. [10]

What Miyagawa meant by “hand-scroll” (emakimono) is this smooth flow of images. In this light, Burch’s observation is perfectly in accordance with the cinematographer’s intention, even though his evaluation is negative. Moreover, the subtle difference between Burch’s use of the “hand-scroll” device and Miyagawa’s is troubling, for this figure was, to my knowledge, originally passed on by Miyagawa via Mizoguchi’s own words:

I was always trying to shoot, with the principle of “one scene/one shot” in my mind. When I first met Mizoguchi, he passionately said to me, “Miyagawa, I’d like to make a film like a hand-scroll (emakimono). My films from now on should be, above all, straight and irreversible like a hand-scroll, which you can look through successively, and don’t have to return to the beginning again once you finish looking. You can smoothly follow the story of this hand-scroll in sequence until the end, and its pictures consist of climactic moments, some strong touches and other weaker ones”.[11]

Considering this claim alongside Miyagawa’s above statement in the Cahiers interview, it is likely that Mizoguchi meant by a “hand-scroll” not so much high-angle camera positions and travelling/crane shots as smooth continuity, which might go hand in hand with those techniques. At the same time, Burch employs the figure of the hand-scroll to refer to the ’30s Mizoguchi camera movement and its effects. For Burch, hand-scroll shots serve to highlight two distinctive devices of Mizoguchi films: lateral traveling shots which pass and penetrate partitions; and higher-than-eye-level camera angles. The former achieves a fusion of two contradictory aspects of space, which is to say, successive stages versus steady flow; the latter results in an “ambiguous presentation of the depth/surface relationship.” [12] Here my aim is not to censure Burch’s use of the hand-scroll trope for its divergence from Mizoguchi’s intentions but, by examining the trope, to open up a possibility of scrutinising how Mizoguchi’s camera did, or did not, undergo a shift. In fact, Burch’s analysis of Mizoguchi’s travelling and high camera positions is certainly productive not only in terms of Mizoguchi ’30s films but also the ’50s work.

Burch postulates that The Love of Sumako the actress is the last work in which Mizoguchi displayed his innovative prewar style. This observation takes on further significance in relation to the cinemaphotography, for The Love of Sumako is also the last collaboration of Mizoguchi and Shigeto Miki, the cinematographer who shot most of the existing prewar Mizoguchi films. [13] When Mizoguchi began their collaboration, Miki had already made a number of successful works as a cinematographer, including Roningai (Japan 1928). Cinematographer Kozo Okazaki, [14] who began his career at the Shinko Kinema’s Oizumi studio as an assistant, describes Miki’s work with Mizoguchi in an interview with Tadao Sato: “[I]t is Miki who created the picture which accorded with Mizoguchi’s mise en scène, by using a 25 mm wide lens, which has a deep focal length”. Then, in response to a question concerning the date of Mizoguchi’s turn to the deep focus, Okazaki answers:

There was the cinematographer Tatsuyuki Yokota, who had teamed with Mizoguchi for a long time. [15] He was also a master, known for Jinsei gekijyo [directed by Tomu Uchida, Japan ??] etc., but I think when he was in partnership with Mizoguchi, he usually used the “normal” lens [by which Okazaki seems to mean 40 mm]. It seems to me that after Mizoguchi moved to Daiichi Eiga and worked with Kohei Sugiyama and Shigeto Miki, Mizoguchi’s style started changing. [16]

Probably because the late Miki worked on relatively low budget B-sword dramas and yakuza films in the Toei studio which were not taken as “artistic” (regardless of their high quality), and because in his lifetime (1902-1968) the early Mizoguchi films he photographed had not yet enjoyed wide recognition across the world, Miki’s work did not circulate as widely as Miyagawa’s. Furthermore, his first two films with Mizoguchi were lost. Comparing The White Threads of Cascades (Taki no shiraito, Japan 1933) to The Downfall of Osen (Orizuru Osen, Japan 1935) however, it becomes clear that while in the second almost all the properties of the prewar-sound Mizoguchi, such as distant camera, deep staging and long take, are introduced, the first manifests silent cinema aesthetics, such as kaleidoscopic montage.

2. The Dialectic of Camera and Acting

Mizoguchi’s films are almost always about women. It is, however, arguable that Mizoguchi strongly gravitates not toward women’s beauty or their sorrows but toward women in social relations, and in particular to hierarchical power relations between the sexes. Mizoguchi’s view is succinctly illustrated in a 1952 interview: “In the first place, I have long thought that after Communism solves the problems of class, male-female problems would remain.” [17] Here his reference to Communism, though seemingly casual, reveals that he considered the male-female relation to be something like class relations, i.e., a historically specific hierarchical system that serves as mode of exploitation. Sato accurately points out Mizoguchi’s profound obsession with “the high/low positions in human relations” and maintains:

In Mizoguchi, even a state of love between a man and a woman is under the sway of hierarchy. Or, for Mizoguchi, the most desirable form of romantic relationships might have been a picture of holding down under him someone noble at whom he used to look up… He recognised that every human relation inevitably takes shape as either the act of looking up or that of looking down, even in romantic relationships. [18]

Sato’s observation is helpful in mapping out hierarchical power/romantic relations in the Mizoguchian world. In effect, modern romantic love, which theoretically bases itself on human equality in bourgeois society, is what his films often eulogise as an abstract ideal, but rarely realise in a concrete form. It is symptomatic that both of the films which preeminently foreground romantic love, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum and The Crucified Lovers, deal with love between servant and master. Needless to say, inter-class romance has been the privileged theme of melodrama, literature and film since the nineteenth century. In this regard the two films share rather conventional plots. Yet, while according to the modern romantic mandate love transcends the class difference between the lovers, and thereby generates two equal, loving individuals, romantic love in these films never overcomes the preexistent hierarchy. On the contrary, hierarchy is ceaselessly re-inscribed into the acts of love. Otoku is legitimised as Kiku’s wife in her death bed; Osan and Mohei, bound on a horse’s back together, are led to the scaffold as equal criminals. To my mind, however, it is not so much that Mizoguchi tried to offer a critical exposition of the feudal society which would not allow the lovers to be equal individuals until their death, as that his films, or his mise en scène, could never do away with hierarchy.

This raises a further question: how are power relations actually registered in Mizoguchi’s films? Sato tries to answer this question, as he implies in his use of the words “looking up/down” in the above excerpt, by focusing on his preference for high angles. According to Sato, in Mizoguchi films a character’s domination over another is represented through acts of looking up/down, which work together with low/high angles. He takes as an example the scene in Ugetsu in which Princess Wakasa (Machiko Kyo) reveals her true nature to her lover, Genzaburo (Masayuki Mori). In fact, the threatening ghost princess’ back is captured by the high angle camera placed behind her, in connection with the shots of her face from the point of view of Genzaburo who sits petrified on the floor. Sato argues that here Mizoguchi registers the princess’ supernatural, social domination over the potter by spatial construction through the respective camera positions. [19]

The matter is, however, more complex than Sato suggests. First and foremost, the analytical breakdown of space in this example is rather exceptional in Mizoguchi’s repertory of spatial constructions. What marks his films is, as I will examine later, the camera that captures both the oppressor and the oppressed within a single frame. Therefore, it is not always valid to claim that the camera angles formally lay out the power relations between characters in the space. Secondly, but of equally significance, unless the camera position is firmly motivated by a character’s psychology (as is the case with POV shots), it is highly questionable whether we could uncritically ascribe this or that camera movement and position to any anthropomorphic meaning, especially in Mizoguchi’s case. It is also misleading to regard high-angle crane shots as Mizoguchi’s dominating gaze at actors or people in the real life. By doing so, we would assume the identification of author with film-narrator too easily.

Setting aside camera movements, is Sato’s related remark that the characters’ positions in space reflect their status in the diegetic hierarchy relevant? In his sophisticated analysis of A Geisha, entitled “Oga to kenryoku [Lying down and power]”, Hisaki Matsuura dissects its intricate fabric of power relations by reversing Sato’s schema. Matsuura points out that in A Geisha, “by placing those with the upcast look in the throne of power, contrary to the common idea, Mizoguchi constructs a thoroughly tense filmic space which naive psychological readings can never penetrate.” [20] To put it more concretely, the rules of the game he deduces from A Geisha are: the dominator occupies the lower position, especially by lying down, while the oppressed occupies the higher position. Presumably Matsuura is alluding to the “naive psychological readings” of Sato, and as far as A Geisha is concerned, his analysis is detailed and convincing. The power relations in A Geisha, mediated by money and sex, are certainly inscribed by the reversed high/low dynamics in a number of scenes, such as when the government official Kanzaki (Kanji Koshiba) brazenly remains lying on a futon when Miyoharu (Michiyo Kogure) is brought to sleep with him against her will. Although Matsuura’s rules are not always applicable to every Mizoguchi film, his “Lying down and power” offers a significant perspective lacking in Sato. Space in Mizoguchi films is always loaded with tense power relations, and the relations are registered by the dialectic of camera and acting, determined not by conventional, anthropomorphic camera positions, but the intrinsic norms of the Mizoguchian world.

What marks Tanaka’s acting? How does it interact with the camera movement, and Mizoguchi’s mise en scène? To examine these points, I will focus on “seduction” scenes from Sisters of Gion, The Love of Sumako the Actress, Miss Oyu and The Life of Oharu. There are several reasons for chosing this particular motif. First of all, it seems likely that male/female power relations are highly legible as they become crystallised in seduction scenes. Also, since in these films sexual politics is always interwoven with a socio-economic hierarchy, seduction can never be purely romantic. Secondly, but equally importantly, in seduction scenes where tension has to be enacted, the four points that I consider crucial properties of Tanaka’s acting are most relevantly mobilised: her smooth, prompt and light way of walking; fluid but restless gestures; inclination to avoid eye contact; and ambiguity in facial expressions. Sisters of Gion serves to clarify the difference between Isuzu Yamada’s acting and Tanaka’s. Finally, each seduction scene has its own distinctive reason for being included in this analysis. To wit: Sisters of Gion exemplifies Mizoguchi’s films in the prewar-sound era; Sumako is a transitional piece which shows how Tanaka acts in the Mizoguchi-Miki space, i.e., his prewar-sound style; Miss Oyu, Mizoguchi-Tanaka’s first collaboration with Miyagawa, reveals her peculiar acting in its seemingly seamless découpage; and Oharu posits a culmination of the Mizoguchi-Tanaka collaboration. Whereas the development of my discussion follows chronological order, I do not thereby mean either to subscribe to the view which accounts for a transformation of the director’s mise en scène as a “maturing process” or “evolution”, or to evaluate late Mizoguchi at the cost of early Mizoguchi.

The above four properties of Tanaka’s acting were exploited by other directors to different ends. For example, Keisuke Kinoshita’s The Army (Rikugun, Japan 1944) capitalises on Tanaka’s smooth, prompt steps and ambiguity in facial expressions (points 1 and 4 of the above schema) to bring the film to its truly melodramatic climax. The mother (Tanaka) runs, searching after her son who is about to be sent to the China front. After she finally discovers her son, lateral travelling shots capture her plowing her way through the excited crowd in order to keep up with her son marching in the army procession. It is well known that this sequence was criticised by the Home Ministry’s censor for failing to glorify the war, and yet it was too ambiguous to be banned. Tanaka’s acting, in cooperation with the overwhelming effect of the travelling camera, hinges on her command of multi-layered expressions rather than enigmatic opacity. Accompanied by non-diegetic music with patriotic lyrics, she registers a variety of emotions which have at last broken through the repression of “selfless devotion to the state”, solely by means of a sequence of facial expressions and the act of running: anguish, joy, affection, ecstatic delight, despair and anxiety. In this sense, she puts her expressive capacities on full display in order to create another layer of meaning that is not verbally articulated, but presumably legible to the spectator. In other scenes of The Army, Tanaka’s fluid, relentless gestures (point 2) contribute enormously to embedding the role of a hardworking woman into everyday details of a lower middle-class milieu in Hakata (a large city in the Kyushu island located south of the Japanese mainland). Her inclination to avoid eye contact (point 3) also works to inscribe her character’s modest personality, as in other Kinoshita films. What I would like to stress is that the four properties of Tanaka’s acting in The Army are not organised into the pattern characteristic of her work with Mizoguchi.

Tanaka’s acting in Ozu’s postwar films, such as A Hen in the Wind ( Kaze no naka no mendori, Japan 1948), The Munekata Sisters (Munekata kyodai, Japan 1950) and Equinox Flower (Higanbana, Japan 1958) marks a stark contrast both twith Kinoshita and Mizoguchi: she looks into the camera, as Ozu’s other actors do. (Particularly memorable is the “staggered/diagonal (sujikai)” [21] exchange of direct addresses to the camera in A Hen in the Wind, between Tanaka and her mirror image at the moment when she makes up her mind to turn to prostitution.) Tanaka’s look in Ozu’s films leads us issues of culture and film. Although Ozu is sometimes alleged to be the “most Japanese” of directors, looking into the eyes (a conduct with which his films played a game) was not a broadly endorsed practice, and was sometimes even taken as embarassing in Japanese society. [22] This suggests that both Tanaka’s tendency to avoid eye contact and contemporary everyday custom are utterly transformed by Ozu’s film language. Likewise, whilst Tanaka’s acting and Mizoguchi’s mise en scène are embedded in, and make use of, multiple facets of Japanese society (from architecture to manners which tend to clearly register the person’s social status), neither of them can be reduced to mere typologisation. My goal, therefore, is to show as a working hypothesis that the Tanaka-Mizoguchi collaboration produced a form of staging specific to Mizoguchi films.

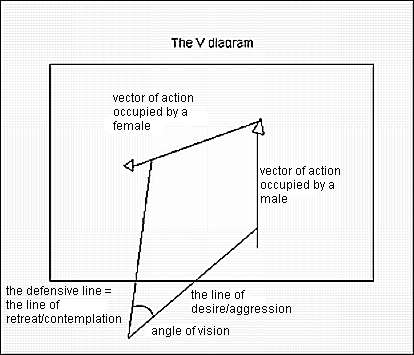

In scrutinising Mizoguchi’s staging, Jean Douchet’s schema, which can be called the “V diagram “, is a splendid tool. Douchet’s diagram is, as far as I know, the only attempt at schematising actors’ movements in Mizoguchi’s films in terms of their relation to the camera. [23] This schematic exposition, based on his recognition of Mizoguchi as “un cinéaste du désir” (“a filmmaker of desire”), does not end up in the gratuitous geometric pattern that its name might suggest, but offers a hermeneutics of actors’ movements. His complicated account of the diagram is worth quoting:

The base is the camera eye filming with an angle of vision that Mizoguchi identifies with the spectator. The right line of this angle of vision will be taken as the axis of desire and of agressivity, therefore of action. The other line will be the defensive axis confronting that desire, namely, the axis which folds onto itself, therefore the axis of contemplation. The V of the angle of vision becomes the V which serves as the device for mise en scène on the screen. Frequently the screen closes the V opened by the camera in such a way that if one made this combination into a figure, it would form a lozenge. In the V visible on the screen, the axis of agressivity and desire is occupied by the male, and the other is ascribed to the woman trying to protect herself from attack. [24]

My interpretation is that the two axes of the visible V on the screen should be conceived not as static lines, but as vectors always in motion. In other words, the two vectors on the screen are not the fixed orbits of the actors’ movements, but ceaselessly self-modifying vectors. (In this sense, the formation of the vectors is not determined by a particular environment, such as the corner in a room where two actors’ vectors inevitably or naturally make a V shape.) When the A vector is assigned to a male and the B vector a female, as Douchet explains, the Mizoguchian actors’ choreography of desire comes into sight.

Although Douchet himself does not acknowledge any fundamental shift or rupture in Mizoguchi’s filmography, [25] in my view the V diagram is particularly relevant to his postwar work. While Yamada’s acting in Sisters of Gion cannot be explicated by the diagram, the first three aspects of Tanaka’s acting style listed above, i.e., her movement and way of looking, are in operation within the V schema. Tanaka tries to move away with her smooth, light footsteps, meanwhile avoiding eye contact. Ambiguity of facial expression (point 4) also works to activate the diagram, but only indirectly. As I will discuss periodically, the very ambiguity of what the character knows about the other, and what s/he her/himself desires facilitates and perpetuates the slippage of the two vectors. These vectors can neither merge into one nor stop moving, because the aggressive one desires to know the other’s desire which s/he her/himself does not know, and thus the former’s desire becomes indiscernible from his/her desire to know.

What is especially extraordinary about Tanaka as an actress is her ability to consummately play not only roles of the oppressed, but also the oppressor. In effect, many women in Mizoguchi’s films, not exclusively played by Tanaka, occupy the position of the oppressor or the dominator. Therefore, while power relations in Mizoguchi films are almost always gendered, it is not that the role of the oppressor is always assigned to the male and the oppressed to the female, as Douchet maintains. The cruelty of the Mizoguchian world resides in its continuous rearrangement of the oppressed and the oppressor; in other words, the power relations do not establish themselves as a stable hierarchy, but organise themselves as a set of multiple micro-politics. [26]

3. The Love of Sumako the Actress: Restlessness in Depth of Field

The successful opening of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House as a historical marker in the development of Shingeki [modern theater] forms the backbone of The Love of Sumako the Actress. Sumako Matsui (Tanaka), who has just been “discovered” by the director Hogetsu Shimamura (So Yamamura) among his drama students, makes her debut as the first star actress in the modern Japanese theater, playing Nora in Ibsen’s play. That night, Sumako and Hogetsu stroll along the street together with Kichizo Nakamura (Eitaro Ozawa). Slightly drunk, they remain in an excited, opening night mood. After Nakamura leaves Hogetsu and Sumako, the actress invites the director to her place.

The seduction in question takes place in a shot-sequence. Throughout the first half of the sequence, Tanaka’s restlessness goes to an extreme within the depth of field. At the beginning, Miki’s camera is positioned in Sumako’s small garden, displaying a wooden fence. We can discern Sumako and Hogetsu through the slits of the fence. Sumako says, “Why don’t you drop in? I’d like to hear more of Magda’s story”, and Hogetsu agrees. The camera promptly dollies left, following their movement, although their figures are barely recognisable because of the fence. This tantalising of the viewer’s perception is, needless to say, characteristic of Mizoguchi’s films, especially those from the late ’30s. Then Sumako enters frame from the left, and Hogetsu follows her. Although the hydrangea between the actors and the camera partially obstructs the viewer’s sight, Sumako races toward her room, and the camera keeps up with the figures by panning. Saying to Hogetsu, “Please come in,” Sumako flies into her room, turning on the light in the middle of the background. The camera stops moving, and distantly frames her room obliquely from outside left. After the light is turned on, we gain a clear view of the whole field thanks to deep focus.

While Hogetsu still stands at the threshold, Sumako quickly turns to the foreground, puts a tray away, and then goes right to the corner in the background to remove her kimonos from a hanger, saying, “Oh, my goodness! It’s really messy, you know, because I’ve been very busy with the theatre”. The camera moves slightly forward, as Sumako throws her kimonos into a closet and brings a cushion for Hogetsu. Meanwhile, Hogetsu moves slightly to screen left, finds leftovers on a small table, and teases her by saying, “Oh, you have such a nice meal”. Sumako immediately comes to the table, saying, “My goodness! Don’t look at such a thing, Professor Shimamura!” then goes behind the shoji screen at the left edge of the frame, carrying the leftovers away, and returning quickly to the frame. Hogetsu moves screen right, and the camera adjusts the frame to his positioning. Sumako turns to Hogetsu’s back, suggesting he take his haori jacket off, helps him do so, and hangs it on the hanger in the background.

Throughout the flow of movement, Tanaka never halts. No doubt, as the uplifting, suspenseful non-diegetic music suggests from the outset, this is a banal, but obviously tense situation: a man visits a woman’s room for the first time. Furthermore, their relationship in the public sphere is one of theatre director/actress, as well as professor/student, which certainly emphasises the soap operatic tension between the two. While her actions could simply be summed up as an act of cleaning, firmly motivated by the character’s psychology and verisimilitude, her restless acting contains a certain excess. The extreme fluidity with which she moves on from one action to another suggests an air of choreography. The choreography of two actors embodies the V diagram, albeit not in its perfect form. Clearly it is Sumako who takes the active part, though without being aggressive. Up to this moment, however, the two actors are positioned in different sections of the field, and Sumako’s and Hogetsu’s vector always form an angle of around forty five degrees: in reaction to Hogetsu’s movement toward the little table in the left foreground, Sumako moves to the right background; when she returns to the table and chides him, he walks right into the middle of the field as if she had pushed him.

In the second half of the sequence, the tempo of the actors’ movements slows down but tension is maintained, or rather enhanced. Screen right, in the middle of the field, Hogetsu (using a round fan) sits down with his back to the closet, and seems relaxed. Sumako also sits down across from him, and fans him. This is the first time they occupy the same section of the field. Asked by Sumako to continue his story about the heroine of their next play, Hogetsu starts talking with his body thrust forward. The two look at each other, but soon Sumako turns her gaze away and brings an ashtray close to him. Then Sumako stands up, and exits frame left. Hogetsu lies down, talking to Sumako, “Oh, I remember an interesting line of hers . . . ” As he lies down, the camera makes a subtle pan right to adjust the composition, and the shoji screen which used to be visible at the right edge leaves the frame. “‘I’ll sing, and beat them by singing. I’ll beat all of them by my song.'” While Hogetsu is reciting the heroine’s line, Sumako re-enters the frame, and sits down at Hogetsu’s feet. Hogetsu continues: “‘I’ll have my own way by my song. This is my way of singing.'” Sumako says, “She sounds just like me,” pouring water into a glass. Around here, the non-diegetic music’s melody gradually approaches exaltation. Sumako reveals her passion for theatre, occasionally casting glances at him: “You know, my feeling when I entered your drama school was just like that.” She offers the glass to Hogetsu, putting it beside him. She starts fanning him, looking at him, but suddenly pauses her action, startled. She withdraws her body, and absentmindedly keeps fanning him. Hogetsu gets up, calling her name, “Sumako!” The music disappears, and the camera slightly rearranges the frame to the left.

The above actions take place in depth of field, so it is hardly possible for the viewer to see the actors’ facial expressions. Hogetsu’s face, especially as he lies down, sinks into the darkness, and it is not clear what makes Sumako pause. Here, Mizoguchi’s mise en scène and Tanaka’s acting reach extreme subtlety. This is an exceptionally sophisticated representation of male desire in a love scene, since Sumako explicitly recoils at the sight of man’s desire expressed in his eyes, or on his face, even if his face is not revealed at all. This motif can be construed firstly as the reverse of the Mizoguchi-Tanaka mandate, “not to look into the eyes”, which will be reasserted between Sumako and Hogetsu in the rest of the sequence. Secondly, a somehwat “reflexive” property of Tanaka’s acting is condensed here. A number of actors, and staff, recollect that in his notorious rehearsals Mizoguchi reiterated this somehow enigmatic phrase: “Are you reflecting?” This sounds more nonsensical in the Japanese original than in English, since the Japanese verb for “reflect”, hanshasuru, does not cover the meaning of “to express” or “to speculate.” The actors seem to have interpreted this phrase as “Can you express the character’s psychology?” which could be right, since sometimes Mizoguchi added the word “feeling” to the phrase, although he did not answer “whose” feeling the actor should “reflect”.

Regardless of what Mizoguchi actually meant, however, the word “reflection” can be employed as a hermeneutic label for the property of his actors’ performance on the screen (as might be the case for Douchet’s essay title). Mizoguchian actors, Tanaka in particular, reflect the other’s desire, and thereby shape her/his recoil with productive passivity. Through the act of reflection, Mizoguchi gives desire an articulation beyond the dichotomy of the desiring subject of the gaze (and of POV), and its object.

Until Hogetsu calls out her name for the second time, he and Sumako keep looking at each other. Only the slight tinkling of a wind chime is audible. Sumako stands up and walks to the corner background with her back to the camera, i.e., she averts her eyes from Hogetsu. Along with her move, the camera shifts the frame to the left. Hogetsu, gazing at her back, stands up and repeats, “Sumako.” She turns to him, murmuring, “Please, don’t. You and I are. . . ,” and comes to the foreground. Hogetsu folds his arms, and the camera moves a little bit backward left. Although Sumako’s face is directed toward Hogetsu, their gazes do not meet since his is cast toward the corner. Here the V shape plainly appears, Sumako being the active vector, Hogetsu the passive. While Hogetsu expresses his self-destructive, fatalist determination to risk his social status as a professor/husband/father/son-in-law, Sumako walks ahead like a somnambulist. Hogetsu states that he had not known any joy until he met her. Sumako looks back, but Hogetsu does not move his gaze from where he fastened it. She leans on the shoji screen in the left foreground, the lamp hung in the middle of the field creating a back light around her head. As Hogetsu says, “Neither my art, nor my life could be animated without you,” Sumako slowly collapses to her knees. The camera pans left a little to capture her through the shoji screen, and the sequence fades out.

I would like to draw three points from this seduction sequence. First, this sequence, particularly its second half, bears a close resemblance to the “Kishibojin temple tea house” sequence in The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, in which Kiku (Shotaro Hanayagi) proposes to Otoku (Kakuko Mori). Certainly part of the resemblance is derived from the common situation of the two sequences: a man from a higher social class confesses his love to a woman from a lower class, putting his social position at risk. More importantly, with the same cinematographer and the same set designer (Hiroshi Mizutani), the camera’s movement and angle are quite similar: both sequences begin with a traveling shot through obstacles, and the couple inside is captured from the outside via deep focus. Furthermore, the woman’s reaction to the man’s confession is almost the same: she stands up, walks, leans on the shoji screen, and collapses, although the front and the back are reversed. But this similarity illuminates the crucial difference between the two sequences in terms of relations between the camera and the actors’ performance. In The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, or rather in Mizoguchi-Miki prewar films in general, the actors’ movement through sections of depth of field is more restricted, and when it happens, it is definite and significant. In Sumako, the heroine ceaselessly moves, and even in the second half she walks through the field and returns.

Second, this seemingly banal, soap operatic sequence contains ambiguity. It is certainly a seduction, but by whom? Perhaps Hogetsu is the subject of the seduction, and Sumako the object. To some extent, however, it can be said that Sumako, by inviting him to her place, staged the seduction. She also always controls the field of action in the first half, and by acknowledging the presence of his desire through her “reflection”, in effect, facilitates his enactment of desire in the second half. This ambiguity of seducer and seduced is characteristic of such scenes in Mizoguchi.

Third, although Tanaka dominates, the social hierarchy between the two is registered in every action. To put it another way, while the Mizoguchi-Tanaka collaboration creates a form of domination which is not necessarily a crude translation of the social hierarchy, it is also obvious that Tanaka’s efficient and tactful gestures fit the role of cleaning and serving. Together with the honorific expressions in the Japanese dialogue, Tanaka’s restless gestures and movements compared to Hogetsu’s slow, contained gestures eloquently enunciate the characters’ positions in the social hierarchy.

4. Sisters of Gion: Manipulation by Glances

In this section, a seduction sequence in Sisters of Gion is analysed in order to spell out how Yamada’s acting differs from Tanaka’s in relation to Mizoguchi’s mise en scène and Miki’s camera. The sequence of the seduction of Kudo (Eitaro Shindo) by Omocha (Yamada) has attracted scholarly attention for its conspicuous use of long take and depth of field. Burch points out: “Here, then, camera movement serves to maintain both distance and the de-centered composition which is its essential complement. More importantly, we begin to see here that Mizoguchi’s systemics often involves as well a particular kind of ‘montage within the shot.'” [27] Donald Kirihara focuses on the crosscutting between the inside where Omocha and Kudo are talking and the outside where the clerk Kimura (Taizo Fukami) is trying to overhear their conversation, in order to argue that this seemingly classical device functions on the contrary to draw the viewer’s attention to itself and to “block out” the smooth deployment of the conversation. Consonant with Burch’s view of “montage within the shot”, Kirihara maintains that the long-take shot in the sequence has an obscuring effect on the spatial construction of the diegetic world. [28]

I agree with Burch and Kirihara’s observations, but I cannot dismiss Yamada and Shindo’s acts as illegible or dissolved into the setting. My focus here will be basically confined to the last shot of the seduction sequence. Three criteria are transferable from my hypothesis about Tanaka’s acting: way of walking; gestures; and eye contact. To begin with, let me examine a couple of key moments of Yamada’s action. The high-angle camera with a deep-focus lens frames Omocha and Kudo sitting in a room. Omocha faces Kudo, who is on her oblique right, with his back to the entrance. His flattery (“A pretty girl and not popular?”) enhances Omocha’s confidence. She casts a quick glance screen left, i.e., toward the area around a brazier (naga hibachi, also used as a tea table), saying, “Talking with you, I forgot to offer tea.” Then she gets up, walks, and sits down at the naga hibachi. The camera keeps capturing her and Kudo by tracking backward. Omocha occupies the foreground with her back to the camera, and Kudo remains in the background. She opens a bottle of beer, and calls him over to the naga hibachi. This is the “montage within the frame” that Burch and Kirihara discuss, and it is an efficacious device not only because it manipulates the spatial construction in a purely formalist way, but also because it enables the camera to display the seduced and the seducer in a single frame. From the perspective of acting, Omocha’s move to the naga hibachi is not gratuitous choreography but the clever tactic of a seducer, aiming to “complete her conquest” [29] by making the man “spontaneously” fall into the trap.

Indeed, Kudo happily joins her, sitting down to face her. Following him down, the camera moves slightly to adjust the frame. Omocha’s action at the naga hibachi is carefully calculated, and supported by confidence: she lights a pipe and gives it to Kudo and changes her seat in front of him to his side, but this increase in intimacy happens only after he is persuaded to “listen to her talk.” She eventually cheerfully declares, “I chose you as my patron! You don’t mind?” While Kudo does not answer, perhaps in order to conceal his joy, she takes his haori jacket off, puts it somewhere off-screen, returns, and lures him to stay there and relax, by helping him with a gown (tanzen). As the two stand up the camera rises a little and the image fades out. Thus, she finally conquers. Omocha’s aggressive, but calculated actions punctuate their dialogue.

It is true that Omocha’s seduction scene differs from Sumako’s in terms of situation: a clever, cynical geisha’s seduction of a rich merchant, with the aim of making him her patron; and a clumsy, serious-minded actress’ seduction of a drama professor, out of romantic love. This difference, however, seems to be connected with some profoundly different characteristics in the acting itself. It would be impossible for Tanaka to play this sort of manipulative seducer. This speculation seems to be confirmed by the fact that Oharu was transformed from an amorous seducer in Saikaku Ihara’s original to the perpetually seduced in The Life of Oharu. In terms of actors’ movement in depth of field, although Omocha and Kudo traverse the space, their movements are more linear, and they never enact the V diagram. The dialectic of acting and camera in ’30s Mizoguchi is determined not by choreography of desire but by “montage within the shot” and drastic changes of composition via camera movement.

One of the possible factors that may affect the acting/camera relations in Sisters of Gion is Yamada’s look, which is of crucial significance in comparison to Tanaka’s acting. In shots preceding the last long take, Omocha and Kudo look at each other during their conversation. Even though their act of looking is not represented by shot/reverse shots, the viewer can clearly recognise that they exchange glances. To take an example, in the third indoor shot of the sequence, Kudo rebukes Omocha for having lured his formerly upright employee into corruption. Omocha daringly gazes at him, saying contemptuously: “Is that so? He’s upright?” If this had appeared in one of the late Mizoguchi films, this kind of “rebuke” scene might be organised as a disconnection of glances to set the V diagram going. In this long take, Omocha’s seduction is successfully staged not only by her gestures and canny talk, but also her seductive glances. While Kudo is complimenting her beauty, she responds to his gaze of desire by glancing back. After they move to the naga hibachi area, her victory is achieved through the flirtatious act of looking.

Isuzu Yamada is an actress who is extraordinarily gifted at “looking”. The first half of The Downfall of Osen is marked by Yamada’s trenchant glances. In the family dinner scene in Osaka Elegy, her glances (which her family never returns) inscribe her solitude. In Sisters of Gion, her confident act of looking, together with Shindo’s gaze of desire, function to rivet their movements. On the other hand, Kinuyo Tanaka is an actress who tends to reflect or deflect the look. In a couple of particular cases in Mizoguchi, however, her look works as the pivot of a film’s whole structure, as my next analysis elaborates.

5. Miss Oyu: The Ambiguity of Looking

Miss Oyu is among Mizoguchi’s most underrated films. Why has this exquisite work, to which the complete “all star staff” of late Mizoguchi rallied for the first time, been dismissed? [30] Mizoguchi himself, who tended to swallow contemporary critics’ evaluation of his work, regarded it as a product of his slump. [31] The grounds for the underestimation seem to converge on two interrelated factors: the original novella, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’s masterpiece Ashikari, was considered too “literary” to adapt into a film; and the persona of Kinuyo Tanaka was quite divergent from Tanizaki’s heroine. The screenwriter Yoshikata Yoda recollects the most agonising aspect of the adaptation: since the heroine Oyu is such a well-bred, unknowing woman, her role in the development of the story inevitably becomes a passive one. Yoda adds, “What was also troubling was that Ms. Tanaka was not like Oyu. It is not at all that she was not so beautiful as Oyu, but that Ms. Tanaka’s cleverness consists of her smart, sensible awareness of everyday life matters. We could not kill this quality”. [32] Yoda is probably right in that the knowing quality Tanaka’s acting expresses itself even when playing Lady Oyu. [33]

Perhaps the best way to appreciate the film is to forget aboutits literary source. When we put aside the original novella, Miss Oyu emerges in a new light. This is a cruel film about the power relations among a beautiful widow (Oyu), her submissive sister (Oshizu), and the brother-in-law who is in love with her (Shinnosuke). The “seduction” scene, which is Mizoguchi-Yoda’s original idea, happens between Oyu (Tanaka) and Shinnosuke (Yuji Hori). The story takes place in an upper-middle class milieu in Osaka in the Meiji era. At a tea ceremony arranged for him by his aunt, Shinnosuke mistakes the beautiful Oyu for the modest Oshizu (Nobuko Otowa) as his prospective partner, and falls in love with her at first sight. He soon learns the truth, but cannot stop his attraction to Oyu. Her husband died young, but she still lives in her in-laws’ home with their child. Shinnosuke is hesitant to marry Oshizu and the marriage arrangement remains in the air. One summer afternoon, Shinnosuke by chance finds Oyu suffering from heatstroke on a bench by the street. He takes her to the house of an acquaintance, and takes care of her. He sends for a doctor, but the doctor tells him she will be all right if she lies quietly. In the meantime Oyu’s family members are worried about her disappearance. The house’s owner is out, and Shinnosuke is left with the still sleeping Oyu.

The following analysis seeks to draw attention firstly to the issue of ambiguity in Tanaka’s acting, and secondly to the V diagram which acts in conjunction with Miyagawa’s camera. What is remarkable in this enactment of the V diagram is that the woman, Tanaka, occupies the vector of the oppressor. The seduction scene, consisting of six shots, can be broken down into three segments, which I will examine in the order they occur: the expression of Shinnosuke’s inner conflicts; Oyu’s coming to consciousness; and Oyu’s persuasion of Shinnosuke.

Shinnosuke sits fanning the sleeping Oyu. She lies in the foreground with her head screen left; Shinnosuke is positioned behind her, at quite a close distance. The clear view of a corner of the room in the background indicates the use of deep focus. Shinnosuke’s face is large enough for the viewer to read an explicit expression of agony. The non-diegetic music (Japanese flute) further evokes the tension of the scene. Then Shinnosuke abruptly tries to bend over Oyu’s body, but immediately recoils from her, turning right with his back to the camera. The shaking Shinnosuke makes another quick turn forward screen right; along with his turn, the camera swiftly tracks forward, and frames him alone in a full shot size. This smooth reframing, probably aimed at dealing with the compositional distance between Shinnosuke and Oyu created by his turn, is adept but somewhat conventional.

Shinnosuke takes a cigarette box out of a sleeve of his kimono. Holding a cigarette in his mouth, he tries unsuccessfully to strike a match with his quivering hand. He tries another, but again fails. With an unlit cigarette in his mouth, he turns to Oyu, and the cigarette drops. He tries to bend over Oyu again, but ends up retreating, turning backward right as he had done in his first attempt. In this series of actions, the camera follows Shinnosuke’s attraction to Oyu with an unobtrusive crane, capturing the two in a single image, and then frames Shinnosuke in the center, without any cutting. The desperate Shinnosuke casts a quick glance at Oyu, but eventually escapes to the veranda (engawa), and sits down. He turns his face again to Oyu, but lowers his shoulders.

The point I would like to make here is about the “unambiguity” of Hori’s acting. Every action he performs in this long take (whose actual length might not be noticed because of the seamless reframing of the camera) registers one single thing: the agony of a man who is split between his desire for the woman he loves and social/moral mandates. Everything, especially his handling of cigarettes, is legible, univocal, unambiguous and transparent in terms of meaning – perhaps it is so well articulated, or rather overdone, as to border on caricature or stereotype. I am not saying that Hori’s acting is one-dimensional in comparison to other Mizoguchi actors. Referring to this scene, Shigehiko Hasumi has remarked that in Mizoguchi’s mise en scène generally, ambiguity is the privileged property of women’s acting, while men’s acting is inclined to be univocal, sometimes almost caricatural. [34] Hori’s turns to some extent suggest a nuance of gratuitous choreography yet, partly owing to Miyagawa’s human-centered camera movement, his expressions hardly offer multiple possibilities for interpretation.

The following shot is a medium close-up of Oyu. At first, with her eyes closed, she seems to be peacefully sleeping. Then, she slowly opens her eyes without moving any other part of her body, and looks screen right. Curiously enough, this shot retroactively creates for the viewer the illusion that the previous shot of Shinnosuke’s back was issued from Oyu’s POV since, at its end, the camera’s position and angle can be roughly identified with Oyu’s look. Then, however, Oyu’s “genuine” POV shot is cut in. This is Shinnosuke’s back, a little tighter than, but shot from almost the same angle as, the end of the long take; Shinnosuke seems to have slightly changed his posture and position. This chain of shots is singular in a number of respects. Firstly, even for ’50s Mizoguchi, so close a shot as the one of Oyu’s bust is quite exceptional. Secondly, a POV shot is rare in Mizoguchi films. Thirdly, and most importantly, how should we interpret Oyu opening her eyes? This action is highly ambiguous. At this moment, it is obvious that Oyu does not try to let Shinnosuke know of her coming to consciousness; she neither speaks nor moves. Furthermore, her slow, calm way of opening her eyes without even blinking makes the viewer doubt if she has really been asleep.

The next shot further deepens this doubt. The first frame is of Oyu’s waist, shot from a high-angle, behind her neck. Oyu, quietly breathing, gazes screen right at Shinnosuke. Then, as she turns her head around to the viewer’s side, the camera (in accordance with the movement of her head) gradually tracks backward, framing Shinnosuke’s back at the veranda in the background and Oyu in the foreground with a clear deep-focus view. Oyu momentarily fixes her look, moves her slightly widened eyes from left to right, and finally raises her head upright. After a deep breath, Oyu begins to speak calmly: “Oh, have I been asleep here?”

Oyu’s silence and eye movements before she speaks out seem to reveal that she is aware of Shinnosuke’s affection for her. It is impossible, however, to know “in fact” whether Oyu is awake during Shinnosuke’s agony, and whether, if so, she keeps silent for a while so as not to embarrass him, or to let something happen. Rather, it is important to acknowledge the ambiguity of Oyu’s look, thereby to scrutinising how this ambiguity functions in the romantic power relations among Oyu, Shinnosuke and Oshizu, as well as the ways these relations are registered. Throughout the many Mizoguchi-Tanaka collaborations, Tanaka’s act of looking is rarely represented by a POV shot, but at least two POV shots ascribed to her play crucial roles: one is this shot in Miss Oyu; the other is Oharu’s look at Buddhist sculptures, with which the flashback begins. In both cases, Tanaka’s expressions flesh out the character as a locus of intense subjectivity but resist any reductive reading of content.

The shot continues. Oyu, raising her torso, thanks Shinnosuke for taking care of her, tells him that she has to hurry home, and gets up. The camera keeps framing the two until Oyu gets up, and then Oyu, fixing her kimono, exits the frame screen left. It should be stressed that, throughout these actions, Oyu’s glance and Shinnosuke’s do not meet, partly because they are separated in the foreground and the background. The following shot, the final one of the sequence, displays Oyu fixing her sash in a plan américain. Asked by Shinnosuke where she planned to go, Oyu replies that she was heading to his place, and comes up to him, looking in his direction. The camera smoothly follows her steps and contains Oyu and Shinnosuke standing on the veranda in a single image. While this time they look at each other, the difference of height between their positions will soon contribute to creating a disjunction of glances. Oyu says to him, “Some time ago, Osumi [their go-between] came over, and told me that you said you wouldn’t marry”, and sits down. The camera lowers slightly. When Oyu asks, “Is that true?” Shinnosuke sits down too, with downcast eyes, and then the choreography of domination begins.

In the rest of the sequence, Oyu plays the part of the oppressor, trying to persuade Shinnosuke to marry Oshizu, her favorite little sister. Given that Oyu might already be aware of Shinnosuke’s love for her, this is obviously a conscious act of control. Oyu asks him, “Shinnosuke, do you dislike Oshizu?” and he tries to look up to her, saying, “No, not at all”, but immediately turns his eyes away. Here Oyu occupies the aggressive vector by gazing at Shinnosuke, and he the passive vector by always avoiding her gaze. The angle between the two vectors is around sixty degrees, which is maintained by the perpetual rearrangement in relation to their movements. Oyu attacks him, demanding, “If you don’t, please marry her.”

Shinnosuke casts a quick glance at Oyu, turns away, walks screen right into the small garden, and then enters the next room. The camera tracks laterally in order to capture him through a partition and reed screen. Then Oyu enters from screen left and ambushes Shinnosuke in the next room. Oyu (crossing the frame from left to right in the foreground) and Shinnosuke (moving right to left in the background) momentarily intersect each other. Eventually both of them settle down in the next room. Oyu is at Shinnosuke’s right, looking screen left; Shinnosuke looks down right. She starts speaking, turning her gaze to him: “I have a closer relationship with Oshizu than with any other sister of mine. Oshizu visits me almost everyday so that I don’t feel lonely. I don’t want Oshizu to be married to the kind of man who wouldn’t allow me to visit her at their home.” Oyu glances down once, but generally keeps looking him in the eyes, while Shinnosuke always averts his look. Oyu’s line, “You won’t mind no matter how often I may come by, will you?” drives Shinnosuke to abruptly turn screen left, towards her, calling her name, but he eventually turns away in the opposite direction, with his back to the camera. Pushed to confess, he says, “No, of course not. I really want to do whatever makes you happy.” Oyu directs her body to him, then crawls up and tries to look him into his eyes, insisting that therefore he should marry Oshizu. Shinnosuke keeps avoiding her look, by turning left, but at last says yes. Further bending her body so as to look at Shinnosuke, she finishes the victim off: “Are you sure?” Shinnosuke says yes again, and shrinks. The sequence ends with a dissolve.

This is, though relatively short, a typical example of late Mizoguchi choreography. It is especially noteworthy that neither the actors’ turns nor the upward/downward movements are psychologically motivated. The V diagram holds sway over their movements, while Miyagawa’s camera keeps action flowing gracefully. As for power relations, the sequence organises itself on the basis of a carefully calculated allocation of knowledge to the two characters and to the viewer. Dominique Païni, drawing attention to Oyu’s POV, remarks: “Hereafter the spectator knows that Oyu knows, and that she lies and especially lies to herself in refusing the necessity and the obligation of desire.” [35] I would argue that Oyu does not refuse her desire, but seeks to fulfill it in another form. Shinnosuke has to fall prey to Oyu, precisely because she knows, and can pretend not to know, his love.

One can agree that Tanaka was miscast as Oyu. Or, to put it differently and more precisely, the gap between the star image supported by her acting style and the role was so large that a number of details in the film (such as the one where the supposedly childlike Oyu tickles Shinnosuke in front of Oshizu) become awkward and even clumsy. In relation to the seduction sequence, however, this miscasting works productively. The opacity of Oyu’s look embodies the result of this miscasting – a knowing actress plays an unknowing lady. One can compare this disjunction to James Naremore’s fine-grain analysis of Lillian Gish’s performance in True Heart Susie (US 1919). Naremore mentions a shot in the classroom in which Gish betrays a mature, knowing face in order to point out “a polar opposition” that her acting brilliantly conveys. “Her performance ranges between innocence and experience, between stereotypical girlishness and wry, sophisticated maturity – the latter quality giving True Heart Susie much of its continuing interest.” [36] Throughout the film, Gish carefully crafts this balance to make the country maiden Susie more complex and interesting than a stereotype.

In fact, Tanaka, a clever actress whose prewar star image was that of a “maternal child woman” like Gish (albeit lacking in the latter’s fragility), does a similar balancing act in roles more fitting for her. On the other hand, the fissure which Tanaka’s opaque look opens up in the Oyu character is neither properly developed nor mended by the other parts of the film; it keeps threatening to pull the film into contradiction. But I believe this makes Miss Oyu intriguing rather than defective. Since Tanaka’s Oyu inevitably appears to be aware of Shinnosuke’s love, the supposedly unknowing Oyu’s persuasion of him can read as an enactment of the sadistic drama of domination. In other words, the vacillation between knowing and unknowing confers upon the sequence the cruel dynamic of romantic power relations.

6. The Life of Oharu: the magnetic field of power relations

The Life of Oharu consists of a chain of seduction scenes. This structure of narrative development is closely related to Tanaka’s acting. It is tempting to say that her “reflective” acting demands not love scenes but seduction scenes in which desire takes shape in the V diagram. Here I will take up Katsunosuke’s seduction of Oharu as the high point of this choreography of desire.

Although the seduction scene gives the impression of being shot in a long take, in effect it is broken down into three shots. The first shot begins on the back of the sitting Katsunosuke (Toshiro Mifune). The camera turns around and follows him walking to the room in which Oharu (Tanaka) settles. He kneels down, and opens the shoji screen, calling her name. Inside the room, Oharu stands, wearing a kimono like a veil. Katsunosuke is positioned screen right in the foreground, and Oharu screen left in the background. When he mentions the letter he has sent to her, she throws him a glance, but quickly turns away again. Considering the vertical and horizontal gap between their positions, the V is produced in a “three dimensional” form. In response to Oharu’s dismissive answer that she burned the letter from him, a low-class samurai, without reading it, Katsunosuke raises his head. The cut is made on this action.

The second shot is taken from the inside, from an angle approximately ninety degrees left of the previous camera position. This cutting is a blatant violation of the one hundred and eighty degree rule, and can be classified as donden (or “sudden reverse” cutting), even though the shift is not as large as 180 degrees. This donden reverses the background and the foreground of the previous shot, but maintains the V vectors of the actors. Oharu and Katsunosuke get into an argument over the superficial elegance of the aristocrats around Oharu. Whereas the seemingly offended Oharu turns away and moves, avoiding Katsunosuke’s gaze, Katsunosuke keeps up with her every move by opening shoji screens. Katsunosuke at last steps into the room, and demands that she admit whether she has refused him because of his class or because of his personality. Since he approaches her, Oharu turns her body away and tells him that she hates him as a person. As she turns, Oharu’s face is revealed to the viewer for the first time in the sequence. Oharu orders him to leave, and states that she will wait for Katsunosuke’s master.

Significantly, it is precisely when she tries to exercise her power as an aristocrat that Oharu takes her kimono-veil off and gazes at Katsunosuke. This time it is Katsunosuke, who has taken her into the inn under his master’s name, who must avert his eyes. Here the aggressive vector and the defensive one are completely reversed. In addition, at the level of historical referents, the kimono-veil was reprotedly worn by upper-class women in order to screen out such gazes. It is remarkable how splendidly it functions in Mizoguchi’s films. Oharu’s act of taking the kimono-veil off registers her willingness to occupy the aggressive vector as the subject of looking.

Katsunosuke discloses the truth that his master won’t come since he told her a lie. Learning this, Oharu turns and breaks into a run in order to escape to the outside. Katsunosuke catches up with her at the threshold and swiftly steps down to the ground. The third shot is juxtaposed by cutting on Katsunosuke’s stepping action. The angle of this shot is ninety degrees right of the second shot. Katsunosuke, kneeling on the ground, apologises and declares his love. Oharu passes in front of him and stops. She reveals that she has in fact read his letter, and laments that their romantic relationship is forbidden by the class system. However, what should be noticed here is not her social criticism per se, but the fact that, in disclosing her affection for Katsunosuke, she keeps avoiding his look. Even when he holds her tight and tries to make her turn to him, showing his determination to run away with her, she does not look at his face.

Oharu frees herself from Katsunosuke, and starts staggering, with her back to the camera, but it is no longer clear why, and from what, she is fleeing. She stops near the fence. The camera follows her move, and frames her standing back in a long shot. Katsunosuke, taking a different route from her, catches up with her. Oharu stands crying, covering her face with her sleeve. Murmuring, “Lady Oharu,” Katsunosuke, struck, kneels down. Oharu throws herself into Katsunosuke’s arms and embraces him. Katsunosuke’s kneeling is certainly a sort of “reflection” on the part of a Mizoguchi actor – Oharu’s desperate ecstasy which might be expressed in her face strikes him, and makes him kneel down. Then, she faints in his arms and collapses on the ground, covered with dead leaves. Katsunosuke takes her in his arms and exits the frame. The camera cranes down so as to place two stone lanterns in the center.

The seduction scene in The Life of Oharu is enacted with extreme elegance, both by the two actors and by Yoshimi Hirano’s camera. The choreography of desire here is not a crude expression of lust but a flow of refined actions and gestures. It should not be overlooked, however, that every graceful gesture registers not only the couple’s love but also their social positions. Oharu’s avoidance of Katsunosuke’s look sets the perpetual slippage of their vectors into motion. While Katsunosuke repeatedly expresses his belief in romantic love freed from the feudal class system, their romantic love is never realised on screen. Why does Oharu faint? I disagree with Robert Cohen’s diagnosis of her fainting as hysteria. [37] Rather, I would argue that Mizoguchi could not picture the euphoria of romantic love outside the magnetic field of power relations. Alain Bergala beautifully summarises the machinery of this sequence: “By means of subtle variations between the outside (the garden where the samurai keeps himself) and the inside (the room of the young woman of high order), with two changes of the 180 degrees axis, the unbreakable barrier of class which divides them is turned over by one embrace so subversive that the young woman can survive it only by fainting.” [38] In other words, in order to flee from the magnet, Oharu has to faint, and Mizoguchi has to have her faint.

Conclusion

It has been often said that Mizoguchi transformed a “good wife/wise mother” type star into the great actress Kinuyo Tanaka. Once we put aside off-screen personal relationships such as the mythic romance between director and actress, it is clear that a film star’s acting cannot be independent of mise en scène, camera and editing. However, this paper started with a tempting question: why can’t the reverse be true as well? Four properties of Tanaka’s acting (prompt steps, restless actions, avoidance of eye contact and ambiguity in facial expression) interact with camera and mise en scène and thereby, through gradual shifts in the late ’40s, play an important role in the formation of Mizoguchi’s style in the ’50s. This style can be called a choreography of desire in which the aggressive vector of one actor and the defensive vector of the other develop a perpetual slippage of movement. Mizoguchi incarnates the power relations between male and female, with which he was obsessed, in this choreographic form.

Lastly, by reading Burch’s trope of emakimono or the hand-scroll against its grain, I would like to reconsider, or rather reorganise, the relation between camera movement and acting. It seems reasonable to call Mizoguchi’s style in the ’50s “human-centred”, composed with long takes and travelling shots. This term might sound as pejorative as did the “long take à la Wyler”, but given that “human-centered” stresses acting performance, it does not necessarily suggest a “character-centered”, modern psychological drama. According to Burch, Mizoguchi fuses two contradictory modes of space – successive stages versus steady flow. The conflation of these modes is, in my view, applicable to Miyagawa or Hirano’s camera in relation to the actors’ actions. In the choreography of desire, actors’ positions ceaselessly change, and in doing so provide the viewer with a new, distinctive view and sense of space. On the other hand, smooth, lateral movements of the camera organise them as a flow in the frame. To put it crudely, it follows that actors in late Mizoguchi films are rather like the partitions or the shoji screens in his prewar sound period.

So what are “actors” for Mizoguchi? Kirihara’s insightful remark seems to offer a key:

By this time [1935] Mizoguchi was notorious for dominating and exhaustively rehearsing his actors, planning their performances free of stray gestures and unexpected posturing. The self-absorbed attitudes and deliberate movements of the characters in The Downfall of Osen reflect this preparation. Actors’ bodies are less seats of personality and more vectors of force and direction. [39]

Certainly Mizoguchi did not believe in the doctrine of actors’ “spontaneity”. The choreography of desire is nothing other than the objectification of both the subject and object of desire. To say this is not to be contemptuous of actors. Tanaka’s bravura lies in her own objectification of herself as a vector.

Footnotes

[1] I wish to thank Tom Gunning, Adrian Martin, Jonathan Rosenbaum and Yuri Tsivian for helpful suggestions and criticism, and my fellow students at the Mass Culture Workshop meeting on November 3, 2000 at the University of Chicago for valuable comments on a draft of this essay. I am also indebted to Sharon Hayashi and Anne McKnight for their editorial help and suggestions.

[2] The Woman of Osaka (Naniwa onna, Japan 1940, no extant prints); Three Generations of Danjuro (Danjuro sandai, Japan 1944, no extant prints); Musashi Miyamoto (Miyamoto Musashi, Japan 1944); The Victory of Women (Josei no shori, Japan 1946); Utamaro and his Five Women; The Love of Sumako the Actress; Women of the Night (Yoru no onnatachi, Japan 1948); My Love has been Burning( Waga koi wa moenu, Japan 1949); Miss Oyu (Oyu-sama, Japan 1951); Lady Musashino (Musashino fujin, Japan 1951); The Life of Oharu; Ugetsu (Ugetsu monogatari, Japan 1953); Sansho the bailiff(Sansho dayu, Japan 1954); and A Woman of Rumour aka The Woman People Talk About (Uwasa no onna, Japan 1954).

[3]For Tanaka’s own recollection of the period, see, Kinuyo, Tanaka, Kawakita, Kashiko, and Nagashima, Ichiro, “Taidan: Jyoyu, kantoku, eiga,” in Firumu senta, special issue on Kinuyo Tanaka (Tokyo: The Film Center of The National Museum of Modern Art, 1971), 6-7.

[4] Sato, Tadao. Mizoguchi Kenji no sekai (Tokyo: Chikuma-shobou, 1982), 128.

[5]Audie Bock, Japanese Film Directors (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1980), 42.

[6] In Japan there had been no “director of photography”, in the sense that the term is used in the US, until the breakdown of the studio system in the 1970s. Although cinematographers like Miki and Miyagawa definitively had decision-making authority over the image of films, lighting engineers also played an important role and had responsibility in creating light and shadow in close collaboration with cinematographers. The relations between a cinematographer and a lighting engineer were not necessarily hierarchical, though it certainly depended on the case. An assistant director of Mizoguchi’s remembers with a sense of respect the enthusiastic arguments that Miyagawa and Ken’ichi Okamoto, the lighting engineer in chief, often had on the stage. (Miyashima, Hachizo. “Jyokantoku ga kataru Mizoguchi sono hito to enshutsu-ho”, in Eigadokuhon Mizoguchi Kenji, edited by Tsutomu Saso and Noriyoshi Nishida [Tokyo: Film Art-sha, 1997], 39.) Also, in many cases the ’50s cinematographers operated the cameras themselves.

[7] For example, it is said that Miyagawa carefully studied the camera movements of The Life of Oharu, which was shot by Yoshimi Hirano (Sato, ibid.).

[8] Miss Oyu, Ugetsu, A Geisha, Sansho the bailiff, A Woman of Rumour, The Crucified Lovers and Street of Shame.

[9]Cahiers du cinéma, no. 158 (Aug.-Sept 1964): 28.

[10] Noël Burch, To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1979), 244.

[11] Shindo, Kaneto. Aru eigakantoku no shogai: Mizoguchi Kenji no kiroku (Tokyo: Eijin-sha, 1975), 313.

[12] Burch, Ibid., 228-29.

[13] Miki made sixteen films with Mizoguchi: Gion Festival (Gion matsuri, Japan 1933, no extant prints); The Jimpu Group (Jimpuren, Japan 1934, no extant prints); The downfall of Osen (Orizuru Osen, Japan 1935); Oyuki the Madonna (Maria no Oyuki, Japan 1935); Poppy (Gubijinso, Japan 1935); Osaka Elegy (Naniwa ereji, Japan 1936); Sisters of Gion (Gion no kyodai, Japan 1936); The Straits of Love and Hate (Aienkyo, Japan 1937); The Story of the Last Crysanthemum (Zangiku monogatari, Japan 1939); The Woman of Osaka; Three Generations of Danjuro; Musashi Miyamoto; The Famous Sword Bijomaru (Meito Bijomaru, Japan 1945); Utamaro and his Five Women; and The Love of Sumako the Actress. Miki changed his first name from Minoru to Shigeto around 1938. Incidentally, Shigeru Miki, the cinematographer of The White Threads of Cascades(Taki no shiraito, Japan 1933), is a different person.

[14] Okazaki also worked with Joseph von Sternberg as the camera operator on The Saga of Anatahan (Japan 1953).

[15] Yokota made as many as twenty-seven Mizoguchi films in Nikkatsu between 1925 and 1930. The only films with extant prints or fragments are, however, The Song of Hometown (Furusato no uta, Japan 1925), The Tokyo March (Tokyo koshinkyoku, Japan 1929) and Hometown (Furusato, Japan 1930).

[16] Sato, Tadao. “Intabyu: Shinko no kameraman wa genzo, henshu made yatta,” in Shinko Kinema: senzen goraku eiga no okoku. Edited by Tadao Sato, Naoki Noborikawa and Sadashi Maruo (Tokyo: Film Art-sha, 1993), 98.

[17] Mizoguchi, Kenji, and Matsuo Kishi. “Mizoguchi Kenji no geijyutsu,” in Mizoguchi Kenji shusei. Edited by Noriyoshi Nishida (Tokyo: Kinema Jumpo-sha, 1991), 60.

[18] Sato, Mizoguchi Kenji no Sekai, 303-04.

[19] Ibid., p. 284.