| Mark Harris, Mike Nichols: A Life Penguin Random House, 2021 ISBN: 978039956242 US$35 (hb) 673pp (Review copy supplied by Penguin New York) |

|

| Robert E. Kapsis (ed), Nichols and May: Interviews University Press of Mississippi, 2020 ISBN: 9781496828330 / 9781496831040 US$99 (hb) / US$25 (pb) 269pp (Review copy supplied by University Press of Mississippi) |

|

Mike Nichols (1931 – 2014) is probably best known outside the US as the director of films such as Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), his career-making The Graduate (1967), for which he won an Oscar, Carnal Knowledge (1971), Silkwood (1983) and The Birdcage (1996), as well as the Home Box Office TV dramas, Wit (2001) and Angels in America (2003), both of which earned him Emmy awards.

Perhaps, he’s also remembered as the male half of the estimable comedy duo of Nichols and May, who performed in clubs and on American TV during the late 1950s, their largely improvisational sketches leading to a Broadway hit, An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May, in 1960 (directed by Arthur Penn). The recording of that show was one of three made by the pair and it won a Grammy in 1962 for Best Comedy Album. (A handful or so of the Nichols and May sketches are accessible on YouTube.)

However, in the US, and particularly in New York, Nichols is equally acclaimed as a theatre director, with many Broadway hits to his name – including Barefoot in the Park (1964), The Odd Couple (1965), The Real Thing (1984), Monty Python’s Spamalot (2005) and a Death of a Salesman revival (2012) – as well as nine Tony awards (from 16 nominations).

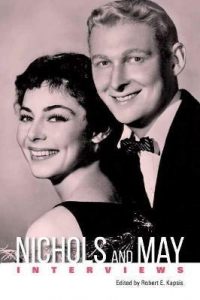

The two books reviewed here deal with Nichols and his work as well as, more or less in passing, with May and hers. One is a conventional biography published by Penguin Random House, which you’ll find in most decent bookshops, perhaps displayed on a table just inside the door; the other is one of the latest in the extensive and generally useful Conversations with Filmmakers series published by the University Press of Mississippi. (In the interests of full disclosure, I should add that I’ve contributed a couple of volumes to the series and have had an ongoing relationship with UPM). It deals mainly with Nichols, but also with May (b. 1932), whose relationship with him continued long after their official performing partnership came to a close in 1961. If you’re lucky, despite the lovely photo of the young Nichols and May on the cover, you’ll find it hidden away somewhere in the back of one of those bookshops amongst the increasingly hard-to-find film books; alternatively, you can order it direct from the publisher or from another of the many sources accessible on-line.

Mark Harris’s fine biography traces Nichols’ life and career from his arrival in the US in 1939 as a seven year-old refugee from Nazi Germany named Michael Igor Peschkowsky (or perhaps, as Harris learned from Nichols’ brother, Robert, it was Igor Michael Peschkowsky) to his death at home at the age of 83 and the subsequent gatherings of theatre and film luminaries to celebrate his life (with, it appears, Harris bearing witness).

In his seventh book for UPM’s Conversations series, editor Robert E. Kapsis offers a thoughtful overview of his subjects and draws together 27 interviews with/features about Nichols and/or May done between 1961 and 2013, several presented in a straightforward Q&A style but most contextualised in more general biographical-analytical formats.

***

Mike Nichols: A Life is Harris’s third book and, like the first two – the groundbreaking Scenes from a Revolution: The Birth of the New Hollywood (2008, Penguin) and the excellent Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War (2014, Penguin) – it’s been thoroughly researched and meticulously footnoted. Surveying Nichols’ career chronologically, it smoothly winds together an account of his often-troubled personal life with expansive production histories of his theatre, film and TV work, punctuating that with insightful commentary.

As in the earlier books, Harris shows himself to be an astute critic and observer of trends. Economically contextualising the workings of the Nichols-May partnership, he writes, “In the mid-1950s, sketch comedy tended to be situation comedy – and the situations were generally so timeworn that audiences knew where the laughs would come before a word was spoken. The first few years of network television had made the set-ups numbingly familiar… To a form that was in serious danger of going stale, Nichols and May brought something slyer, sharper and wholly new – a comedy rooted in deep observation of the tics, vulnerabilities, insecurities, vanities, and pretensions of others, and of themselves.” (p. 59)

Harris is also excellent in the ways he goes about identifying Nichols’ preoccupations as a director. He leaves us to draw the connections between his subject’s depression after his split with May and how, when he saw Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? on stage, he would have been (borrowing Nichols’ words) “uncomfortably familiar with the way ‘the two main characters compete in recruiting the audience to their side’ and with how ‘they enjoy each other’s prowess…’ So, Harris asks “What was Virginia Woolf if not the story of a long and dangerous improv?” (p. 125)

Then, a few pages later, with Nichols in preparation for the theatrical production of Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park (Nichols’ Broadway debut), initially reluctant cast member Robert Redford asks him what on earth might have interested him about the play. “Plenty,” said Nichols, who knew how much could be made of the push-and-pull between an uptight man and a smart, alluring woman who alternately attracted him and drove him crazy. “It’s a battle,” Nichols told him. “These two are in a full-scale war.” (p. 125) The words come from Harris’s interview with Redford.

Discussing Nichols’ interest in Benjamin Braddock, the protagonist of The Graduate, Harris (guided by his interview with Nichols, done during the time when he was writing Scenes from a Revolution, in which The Graduate has a starring role) sees a clear link between the director’s increasing affluence and Benjamin’s alienation. “At the time,” Harris writes, “Nichols, who was acutely aware of how much his own life had become about buying whatever he wanted, and of how little pleasure it gave him, started to see The Graduate as the story of a young man suffocating beneath a surfeit of material goods while he himself is treated as a prized possession.” (p. 211)

Harris’s approach here is not in accordance with the traditional auteurist line: that is, one which seeks out a creator’s thematic and stylistic continuities and developments from one work to another. Instead, his goal is to excavate links between Nichols’ state of mind at a particular points in time and the films and the plays he’s working on at those times. And his growing appreciation of the options provided by film techniques and budgetary possibilities. Sometimes, there’s little to find: Harris recognizes that many of Nichols’ choices were wrong-headed (like the troubled production of Catch-22, which became known on the set as “Kvetch-22”, and The Fortune) or a waste of his time (like What Planet Are You From?) and that there were also times when he was simply going through the motions. But when he’s able to identify what might be driving Nichols – and it’s always a “might”, Harris sensibly holding back from ascribing clear-cut motives for Nichols’ involvement in a project – it enriches the human drama at the heart of his biography.

For his portrait of the artist as a man who, whatever other talents he might have had, was destined to be a director, Harris has drawn extensively on original interviews that he’s done with a wide range of Nichols’ collaborators and other professional colleagues, as well as numerous friends and intimates (including three of his four wives). There’s an alphabetical list of them in the Acknowledgments at the back of the book, and it covers two and a half pages. Which is not to say that Harris has unquestioningly accepted everything they had to say to him. Some of the anecdotes about Nichols have the air of the apocryphal about them, and Harris is wise to this.

The Nichols who emerges from the book is something of an enigmatic figure, as is evident in the conflicting views Harris draws on in reference to the director’s skill with actors and crews. While many of those who were consulted sing Nichols’ praises, others frown over their discomfort with his sometimes tyrannical ways.

Looking back on her experience working with him on Silkwood, Meryl Streep is unqualified in her praise: “‘He would take an idea from anybody,’ she says. ‘He wasn’t threatened by other people, and many, many directors are – when you say something, you can just see them bracing themselves. Mike never did that, and it was glorious.’” (p. 369) The book’s account of the director’s ongoing collaboration with Streep is one of its major highlights, unexpectedly moving in the way it captures their mutual excitement at working together. Harris also cites Silkwood writer Nora Ephron’s enthusiastic description of Nichols’ approach in rehearsal and on the set: “‘Mike… basically uses metaphors to direct actors,’ she said. ‘He’ll say, ‘It’s like when you were in high school and nobody would choose you.’ This gives an actor a way to connect to his character through some mutual experience.’” (p. 370)

It was altogether different during the shoot for The Day of the Dolphin (1973), though, as Nichols became increasingly aware that the project was doomed. “He got so brusque with the crew that toward the end, he told his cinematographer, William Fraker, that he wanted to apologize to his team for the way he had behaved. Fraker shook his head. ‘It’s too late for that,’ he said. Nichols had had a similar warning five years earlier from Robert Surtees on The Graduate, but this time, ‘it took my breath away,’ he said.” (p. 285) And after he had mercilessly berated Garry Shandling during the shoot for What Planet Are You From?, Annette Bening “intervened and told Nichols privately that she couldn’t stand to see him behave that way towards a colleague”. She recalled the incident to Harris: “‘I’m sad to say that Mike just treated Garry terribly, in a way that I had never seen. He was humiliated.’” (p. 504)

Finally, the overall impression that Harris conveys is that Nichols was a complicated fellow whose life away from his creative endeavours often affected the way he went about his work. A troubled human being, he was prone to fits of depression and fears of becoming destitute; there was a time when he became addicted to Halcion, a drug prescribed to deal with his insomnia which had devastating side effects on his personality. Harris quotes Nichols’ friend Jack O’Brien’s assessment of him: “‘[Mike] told me, ‘I was a terrible person for a long time.’ I don’t think he was, but it was clear that the drug period was bad and that he felt he had been mean to people. I mean, there was a lot of broken crockery behind him.’”

Harris also includes Steve Martin’s description of what he could be like: “‘I remember walking down the street with Mike trying to convince him to direct [The Jerk],’ says Martin. ‘This was at a point when he was saying no to everything, and the more he said no, the more people would ask him. I said, ‘What a beautiful night,’ and he looked up at the sky and said, ‘Yes – isn’t it ironic?’” (p. 331) But, as Whoopi Goldberg and others discovered, he could also be inspirational and enormously generous in the support he gave to many who crossed his path.

And the weight of the testimony provided by his peers makes it clear that, when he was at his best, he was a gifted shaper of material, whether on the stage or the screen. Harris traces the course of his development from his time as a beginner, learning about his craft, working with the Chicago-based Compass Players, attending courses run by Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio in New York – “‘What I didn’t really understand,’ he said later, ‘was that [Strasberg] was not only teaching acting, he was teaching directing.’” (p. 44) – to his fame as sought-after veteran who knew how to make things work. He became legendary for the inventive methods he developed over the years to help casts get in touch with their audiences and their characters. “‘Elaine and I had a rule,’ Nichols said. ‘Never try for a laugh. Get the laugh on the way to something else. Trying for it directly is prideless and dangerous, and the audience loses respect.’” (p. 60) It was a rule he maintained throughout his career.

During the Broadway run of Neil Simon’s Plaza Suite, when Maureen Stapleton came to him unable to understand why a scene wasn’t working, he knew what to do. “Stapleton said, ‘I lost a solid built-in laugh. I tried everything I knew to get it back, but it wouldn’t come. I called Mike and asked him to… see if he could figure out what I should do. Mike came to a performance and afterward said, ‘Just take the second half of the line an octave lower.’ I did what he told me and like music to my ears the laughter rolled over the footlights.’” (p. 243)

Several passages in the book outline how he astonished actors struggling with their roles during rehearsals for the theatrical productions of The Prisoner of Second Avenue, Uncle Vanya and The Gin Game. He would switch off the lights, have them lie down together on couches placed in the performance space, and whisper their lines to each other. In every case, it worked. As Clive Owen who worked with Nichols on Closer (2004) put it to Harris, “‘He put you in a place where he made you feel you could do it, and then he let you go and made you want to deliver for him.’” (p. 543)

In many ways, Harris’s book is an exemplary biography. As the footnotes indicate, he’s searched far and wide to try to make sense of his subject. If he hasn’t exactly nailed the essence of who Mike Nichols was, he’s got as close as one could reasonably expect. His beautifully written portrait of the artist as a man, a director, a social being, a husband, and a lover might not exactly amount to a warts-and-all one, and there are gaps in his story. The Jesuits used to say, “Show me a boy at the age of seven and I’ll show you the man.” But, except in passing, Nichols’ formative years before he arrived in the US are ignored. As is what he was like as a father. And the questions regarding his longstanding friendship with photographer Richard Avedon – was it purely platonic, or was there more to it? – and, indeed, regarding his relationship with May remain unanswered. Those, however, are minor quibbles: all biographies are, by their very nature, incomplete. However, this is one that doesn’t shy away from its subject’s dark side, that offers real insight into his work and working methods, and that provides a vivid sense of the shape of his life.

***

As a significant influence on Nichols’ life, Elaine May makes regular appearances in Harris’s biography in a supporting role. In Robert E. Kapsis’s interview collection, however, she gets to share top billing. But, alas, even though she’s a participant in almost half the pieces on offer, she’s still very much a shadowy presence: maybe a bit like Fran Leibowitz with her cryptic putdowns; perhaps a hint of her playing the wacky Annie Hall to Nichols’ fretful Alvy Singer.

Part of the reason for her relative obscurity is that she’s always been a reluctant interviewee, which, in the world of modern media, effectively assigns her to a secondary role. Harris appears to have got her talking in a way that none of her interviewers in Nichols and May: Interviews managed to. Most of its interviews with May turn out to be journalists’ accounts of trying to draw her out about her work and failing.

In a 1962 piece from The New York Times, Richard F. Shepard effectively gives up trying to get anything substantial from her when he wins an audience with her during a rehearsal break for her play, A Matter of Position. Instead of the hoped-for profile, he prints their hugely uninformative exchange verbatim. “What inspired you to write this play?” he asks. “I don’t know,” she replies. And so on. It’s only mildly amusing.

Los Angeles Times writer Joyce Haber offers an engaging account of their 1968 meeting, ostensibly to talk about “a forthcoming movie”. They never get to the film, May seemingly using Haber as her comic foil (a stand-in for Nichols perhaps?), getting her name wrong, and riffing on about the failures of the phone company and about how confusing life can be. Dick Lemon, in a 1970 New York Times feature entitled “How to Succeed in Interviewing Elaine May (Try, Really Try)”, makes May’s reluctance to talk his subject, in the process evoking something of her deadpan humour. (A subsequent article on the making of Ishtar, by David Blum, for New York magazine, refers to it as “brainy humour”.)

She’s unusually forthcoming in her public 2006 conversation with Nichols at New York’s Walter Reade Theatre (the transcript was originally published in the now apparently defunct Film Comment). Allowing time for audience questions, they talk freely about their careers, their work together and separately, how difficult Walter Matthau could be as a collaborator, and the movie business in general. Sam Kashner’s 2013 Vanity Fair interview with the pair also catches the same kind of relaxed tone, May explaining during the course of her chat that she’s always uncomfortable doing interviews. “‘We had so much fun at lunch,’ she said, ‘Now look at us. I’m nervous and terrible at this.’” (p. 225)

In sharp contrast, Nichols emerges from Kapsis’s collection as a good talker, happy to expound on whatever topic the interviewer throws his way, the kind of interviewee whom journalists approach knowing that they’re going to end up with more than enough useful material. Perhaps we could do without some of the material about him, like New York Times film critic Vincent Canby’s tedious 1966 “colloquy” after interviewing Nichols, and Charles Champlin’s lightweight opinionating for The Los Angeles Times in 1988. But the articles generally constitute an invaluable mix, approaching the director and his work from a variety of angles.

In his 1998 article for The Los Angeles Times, Patrick Goldstein takes an auteurist line, proposing that secrets are central to Nichols’ work. “Most of the sixty-six year old director’s movies are about secrets,” he writes, “In particular, the messy concealments that come from sexual conflicts…” (p. 163) The director is happy to roll with the idea and on into a discussion about how that’s pertinent to Primary Colours (1998) and why it appealed to him as a project. In the best straight Q&A interview in the book, one that seems to stretch Nichols a bit more than he’s used to, Gavin Smith, writing for Film Comment in 1999, raises the idea that Wolf (1994) is almost a mirror image of Regarding Henry (1991): “Both are stories of transformation, of discovering a new self,” he proposes. And Nichols is more than open to the idea. “Well, yes,” he replies immediately. “(A)ll my pictures turn out to be all about transformation, actually. Transformation and awakening are very powerful themes in our lives. But this was not a conscious… I didn’t send agents out to look for stories of transformation; this is what I was drawn to.” (p. 177)

Most of the interviews with Nichols in the book are, more or less, genuflections at the foot of the artist, which is fair enough, although seeing him defend himself, or his work, against some substantial criticism of it could have been illuminating. Although it’s more of an opinion piece than an interview, only Frank Rich’s “The Misfortune of Mike Nichols: Notes on the Making of a Bad Film”, written in 1975 as a profile for The New York Times* really wants to engage with the director on issues that might challenge him. It’s worth quoting his commentary at length, because it really throws down the gauntlet to the director.

Watching Nichols at work on The Fortune (1975), Rich became aware of how “(he) always kept his feelings in tight control”. “His response to calamity,” Rich writes, “was always to drift off into an edgy silence, light another cigarette, and stare intently at the bustling technicians around him; such behaviour always seemed more unnatural than a shouting match or a temper tantrum would have under the circumstances.”

“Nichols’ working manner,” he continues, “his ability to project a smooth and usually affable presence no matter what he was feeling inside, soon became inseparable in my mind from the tension that informs his work. The frothy surfaces of Nichols’s movies, whether a successful effort like Carnal Knowledge or a failure like The Fortune, may be, in the end, window dressing – a gloss designed to dodge a forthright expression of the misanthropic sentiments that underlie such projects.”

Compellingly, he concludes, “(Nichols’s) view of humanity is not an optimistic one… and he owes it to himself to face up to the fact, to stop distancing himself and his audiences from what he really has to say by putting on a clever face. (He) does have a vision; his job now is to let it flower… even if it means that everything will be less ‘wonderful’ and that he will lose a few friends.” (p. 79)

I’ve always believed that the best film critics are the ones from whom you can learn something, who can make you see a work afresh, or at least encourage you to rethink your view about it. Rich’s essay does this, whether or not you share its estimation of Nichols as a filmmaker or theatre director. Even better, it manages to prevent Nichols from entirely controlling the conversation about his life and work, which is always an aspect of the give-and-take between an interviewer and his/her subject.

Along with Kapsis’s workmanlike introduction contextualising the interviews, Robert Rice’s excellent 1961 New Yorker profile of Nichols and May, and, in a much lighter vein, the enjoyable 2003 Newsweek Q&A by David Ansen and Marc Peyser with the writer, director and cast of Angels in America, and several of the other interviews already mentioned, Rich’s commentary makes Kapsis’s collection a worthwhile investment for anyone interested in American popular culture during the second half of the 20th century.

Thankfully, the book’s flaws are few. Although the entries never descend to the press-kitty gush that fills critics’ in-boxes in the guise of background information (and sometimes ends up in their published commentaries), there’s way too much repetition of biographical information – virtually every profile includes, with minor variations, accounts of what the seven year-old Nichols said when he first arrived in America, how he and May first met and how they worked with each other (“She’d fill things; I’d shape them”) – and one gets the sense that Nichols in particular wouldn’t hesitate to continuing using a line if it worked the first time around. He wasn’t to know that they’d end up being repeated ad nauseam in a single volume.

The book doesn’t include “Making It Real”, John Lahr’s fine 14,000-word essay for The New Yorker (February 21, 2000), centring on his interview with the director on the set of his disastrous What Planet Are You From? (2000), which is a pity. It’s first-rate writing and it clearly left its mark on Harris’s biography (as he acknowledges). Even if it’s way too long to suit the format for UPM’s Conversations series, it would have been nice to have it rescued from the vaults for a work like this.

* Bizarrely, Kapsis misidentifies the source (p. 74)