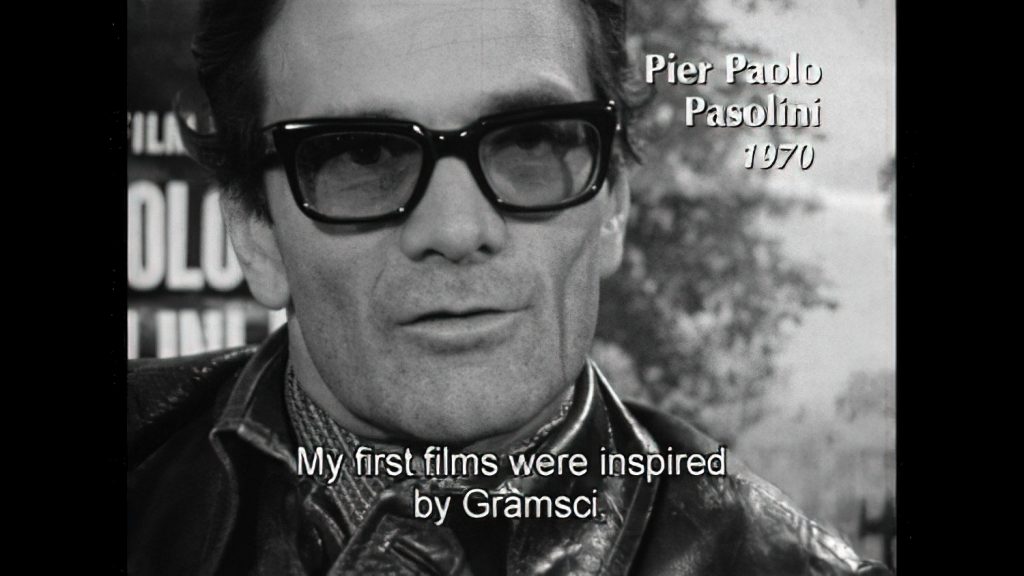

No film director, local or foreign, can claim such an impact on the politics and the arts in Australia now as the poet, communist and homosexual, Pier Paolo Pasolini, dead now for more than 20 years. (David Marr, 1998)

When it comes to classification in Australia, no film has had quite the same history as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom (Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma, 1975). Initially banned upon its release in 1975, Salò was eventually granted an R18+ classification by the former Film and Literature Board of Review in 1993 for less than five years before having its classification revoked by the Classification Review Board in 1998. The film remained banned in Australia for another twelve years until 2010 when its R18+ classification was reinstated, making it legal for adults to see for the second time since its release. This article considers why Pasolini’s film attracted so much censure and, in particular, focuses on the twelve-year ban of Salò between 1998 and 2010.

Salò’s long classification history and battle with the censors raises important questions about the state of censorship in Australia and the inconsistencies inherent in our classification system. The introduction of the Classification (Publication, Film and Video Games) Act 1995 (the Act) as federal law, ratified longstanding socio-political anxiety and public fear around images of explicit sex, sexual violence, child pornography and other deviant sexual behaviours such as sadomasochism and fetishism. Under the newly formed National Classification Scheme, which came into effect on 1 January 1996, a set of legal guidelines and principles would come to govern classification decisions in Australia. However, the application of these principles and guidelines would rest in the hands of the members of the classification and classification review boards, who over the years have applied them in remarkably inconsistent and varying ways. Salò’s classification saga is just one case in point.

The first principle established in the National Classification Code (the Code) is that “adults should be able to read, hear and see what they want.” [1] This fundamental notion is (unsurprisingly) qualified, by subsequent principles that “everyone should be protected from exposure to unsolicited material that they find offensive” and “the need to take into account community concerns about: (i) depictions that condone or incite violence, particularly sexual violence; and (ii) the portrayal of persons in a demeaning manner.” Further restrictions are placed on the enforcement of this principle under Section 11 of the Act which lists four considerations that must be taken into account during the classification process. Of particular relevance here, is the need to consider “the standards of morality, decency and propriety generally accepted by reasonable adults” and “the literary, artistic or educational merit (if any) of the publication, film or computer game.” Additionally, the Guidelines for the Classification of Films (the Guidelines) stipulate that a film must be refused classification, read banned, if it contains gratuitous, exploitative or offensive depictions of sexual violence, cruelty or real violence; or gratuitous, exploitative or offensive depictions of sexual activity accompanied by fetishes or practices which are offensive or abhorrent, incest fantasies, or other fantasies which are offensive or abhorrent.

The 1995 Code also states that films must be refused classification if they “depict in a way that is likely to cause offence to a reasonable adult a person who is, or who looks like, a child under 16 (whether or not engaged in sexual activity).” As will be discussed later in this article, the youthful appearance of the characters in Salò was of major concern for the members of the 1998 Classification Review Board and was used to justify their decision to ban the film. Interestingly, this consideration was amended in the 2005 Code to read those films which “describe or depict in a way that is likely to cause offence to a reasonable adult, a person who is, or appears to be, a child under 18 (whether the person is engaged in sexual activity or not)” (emphasis added). The increased threshold concerning the representation of children from 16 to 18 highlights the growing anxiety over the depiction and sexualisation of young people in media, and elsewhere. In their Explanatory Statement, the Censorship Ministers stated that this amendment would continue to ensure the prohibition of child pornography but would not “adversely effect the material that is permissible in dramatic films” (Explanatory Statement). Despite this, one of the reasons given by 2008 Classification Board in justifying their decision to deny a modified version of Salò an R18+ classification was that the film contained offensive and exploitative depictions of people who were, or appeared to be, under the age of 18 (Classification and Review Board Annual Report 2008).

Salò: Going to the Extremes of Propriety

Pier Paolo Pasolini was one of the most famous modernist directors of his time. Some even consider him to be one of “the most sophisticated directors . . . of all film” (Salvage, p. 86). He received great critical acclaim throughout his career and, before his murder in 1975, won numerous prestigious awards for his films including: Best Screenplay and the Jury’s Special Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival in 1958 and 1974, respectively (Festival de Cannes); three Silver Ribbons from the Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists in 1960, 1965 and 1967; the Special Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1964 (la Biennale di Venezia); and the Silver Bear and Golden Bear in 1971 and 1972, respectively, at the Berlin Film Festival (Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin).

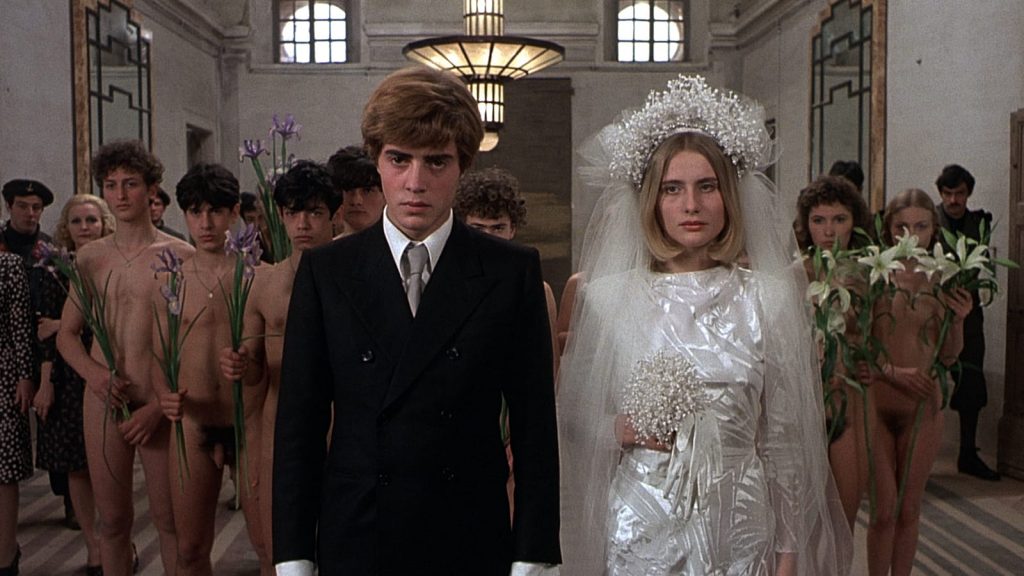

Salò, an adaptation of the Marquis de Sade’s infamous novel 120 Days of Sodom, is Pasolini’s last and most controversial film (Tropiano, p. 215). Set in 1944 Italy, during World War II, four powerful Fascists abduct a group of young men and women and imprison them for 120 days in a remote chateau in the Republic of Salò. Here these young victims are subjected to inconceivable acts of torture, depravity and physical, mental and sexual humiliation. According to Pasolini, Salò was his “first modern film about the modern world” (qtd. in Salvage, p. 91). These depictions of extreme cruelty are intentionally used as a metaphorical statement about the corrupting effects of fascism, absolute power and exploitation (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p. 150; Lane; Indiana; see also Pasolini). Forty-five years after its release, the film maintains its ability to shock audiences and has been called everything from nauseating to a masterpiece. Pasolini’s unforgiving portrayal of human degeneracy and his unwillingness to compromise his work for mainstream sensibilities is notable. However, it is these artistic choices which would also guarantee an ongoing battle with the censors.

Salò has been released for public exhibition in Britain, the United States, France and Japan and was publically screened in Australia prior to its 1998 ban (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p. 150). However, even though the film has been widely distributed in the US and Europe (Browne), it has not been without controversy. Cries for censorship by those who consider Salò to be gratuitously graphic, depraved and offensive have followed the film around the world. In 1994, an American book shop owner was prosecuted for selling the film in his store. While in Britain Salò has rarely been shown uncut and did not receive a video distribution certificate until 2000 (Mallett, p. 84). Upon its release the film was briefly screened in Frankfurt and Stuttgartbut, Germany but was stopped after protests by the Catholic Parents Association. And, of course, there is Australia’s own censorship saga. As the boundaries of acceptable cinematic representations go, “Salò goes to the extreme of propriety” (Mousoulis). It is such extremity which has made the film a controversy around the world and guaranteed its notoriety.

Critics of the film have called Salò immoral and irresponsible, accusing Pasolini of provoking violence and glorifying rape by creating a film that is so completely outrageous and gratuitously graphic (Mallett, p. 84; Mousoulis). Others agree that Pasolini intentionally created Salò to shock audiences, but also believe that the film has deeper significance and social merit. Robert Mallet, for instance, in his review of the film, suggests that rather than simply attacking Salò for its supposed immorality, these disturbing images should be understood as “designed to awaken a slumbering society and to warn them of past horrors” (p. 87). Like Mallett there have been others willing to defend Pasolini’s work and the importance of his final film. Australian journalist and influential social commentator David Marr, in an article written for The Sydney Morning Herald entitled “Art vs Innocence,” stressed Salò’s value as a “study of extreme human degradation.” Another advocate of the film is Mark Spratt, director of Australian distributing firm Potential Films. When asked in an interview with Bill Mousoulis about the potential harmful effects of Salò, he stated:

It carries with it a great deal of intellectual thesis and stylisation. It may be disturbing or disgusting, but that’s its point! I think you’d have to hypothesize a film in which state brutality, intolerance, racism, child abuse and inhumanity were in some way not disturbing or an acceptable alternative to our values to call it potentially harmful.

There is no doubt that Salò is a confronting, challenging and at times difficult film to watch. Nevertheless, it has been well established as an important film by one of the twentieth century’s most significant Italian filmmakers. Even the majority of the 1998 Review Board acknowledged the importance of Salò to anyone studying Pasolini’s work (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p. 149). Despite this recognition Salò has been subjected to more censorship battles than any other film that has come before the Australian classification system (Mills, The Money Shot, p. 127; Browne; Marr, “Art vs Innocence”). This article asks why.

Family Values Vs. Art: The Rise of the Religious Right and Growing Conservatism in the Howard Era

The theatres and video stores of the Western world offer a glut of more violent, more sexually explicit, more frankly disgusting movies that hardly anyone objects to, but Salò remains, to borrow a phrase, off the reservation, proscribed, unacceptable. (Indiana, p. 90)

In the sixties art was a defence to obscenity; it was the key (Marr, 1999, p. 183). That art could redeem what was perceived as an offensive, immoral and dangerous film like Salò made Christian groups throughout Australia furious (Marr, 1999, p. 185). So began the religious right’s fight to ban Pasolini’s film. According to Marr, in his book examining the influence of the church on Australian politics and freedom, The High Price of Heaven, Salò was “stalked by the forces of censorship ever since its release” (p. 193). Adamant that the film set new low standards of extreme sexuality and violence, Salò became a “rallying point for everything the conservatives thought was wrong with the Office of Film and Literature Classification” (Brown, qtd. in “Deliver Us From Evil”). The 1993 Board of Review had released Salò because they argued that although the film was brutal, revolting and hard to watch, it was still a great work of art by a great filmmaker (Marr, 1999, p. 185). However, according to some conservatives, such as former Liberal Party Senator John Tierney and National Party Senator Julian McGauran, the 1993 board had placed far too much emphasis on Salò’s value as a work of art. When the National Classification Scheme was implemented, art was no longer a defence to obscenity. Art was “downgraded” to a mere consideration that the boards should take into account when classifying a film (Marr, 1999, p. 183). Senator McGauran rejoiced in this, revealingly stating: “I’m actually over the moon that the artists have been pulled back into line . . . artistic merit doesn’t mean much to me” (qtd. in Lane). In effect, the new classification laws meant that Salò’s release could no longer be justified solely on the grounds of its artistic merit. In line with the 1995 Classification Act and increasingly conservative socio-political landscape, the 1998 Review Board would not put artistic merit on as high a pedestal as the former board members had. The ability to stifle artistic freedom with their own brand of decency, morality and propriety was seized upon by conservatives in Australian politics.

For the five years prior to its classification review in 1998, Salò was unbanned and free for adult consumption. It is impossible to measure exactly how many Australian adults saw Salò during this five-year period. However, despite its notoriety, by all accounts the film had “exhausted its small audience” in Australia by the mid-nineties (Marr, 1999, p. 90). Why then did Salò find itself subject to further censorship? The increasingly stringent and regulatory regime of the classification system in Australia can be seen in many of the classification decisions made by the Classification Board and Classification Review Board during the late nineties, naughties and beyond. Harsher guidelines and classification decisions to ban films like Salò, and others such as Baise-Moi (2000), Ken Park (2002) and A Serbian Film (2010), further restricting the freedom of adults to watch what they choose, evidences what those in anti-censorship circles have called a “censorship creep” in Australia (Watch on Censorship; Mills, “Film Censorship”). As a film which challenges notions of decency, morality and propriety, Salò was used as a means of political point-scoring, targeted by Christian politicians as “a gesture of power” (Marr, 1999, p. 90) in an increasingly nanny state. The re-banning of Salò reflects the socio-political agenda of the Howard administration (1996-2007) and a period dominated by a liberal conservatism indicative of the government at the time.

Although social conservatives had lost much of their influence during the eighties and early nineties (Maddox, p. 76), John Howard’s right leaning campaign revived the ties between religion and politics in Australia. The Howard administration “assiduously cultivated” conservative Christian ideals (Maddox, slip jacket) and put family values back on the political agenda. As Marion Maddox states, in God Under Howard: The Rise of the Religious Right in Australian Politics, Howard willingly exploited the social agenda of the religious right and “embrace[d] the extreme end of conservative Christianity” (Maddox, p. 74). Backed by the Lyons Forum, a group of right-wing Christian Coalition MPs, fundamental to Howard’s ascendancy during his reign as Liberal Party leader, Howard ran a “successful family values crusade” (Maddox, p. 30). The rise of the religious right in Australia and socio-political agenda of the Howard government had a real impact on the arts in the nineties and early naughties and provides an important context to understanding the censorship of Salò. The success of Howard’s family values campaign meant that publicly defending the liberty of the screen came to be considered bad politics, even though polls suggested that around 70 per cent of Australians at the time believed that adults should be able to see, hear and read what they want (Marr, 1999, p. 76). As Marr explains in The High Price of Heaven, liberty was not the issue in the nineties; it was the problem (p. 80).

While statistics suggested that the Australian public overwhelming supported the notion that adults should be free to make their own consumer choices, politicians discovered it was not the typical Australian that decides who runs the country, but the “anxious, at times vindictive, often militantly Christian 30 per cent” (Marr, 1999, p. 77). Howard’s readiness to use family values as a means of obtaining this Christian, conservative vote further supported his rise to power (Maddox, pp. 71-106). One target of this campaign was Australia’s classification system. In implementing his crusade for stronger family values, Howard promised that he would tighten film and video censorship in Australia (Maddox, p. 75). To ensure this happened, he would rid the classification boards of all the “experts and city types” that were currently appointed and replace them with “real” Australians (Marr, 1999, p. 184). The Howard government claimed that these “experts” were unrepresentative of ordinary Australia and therefore out-of-touch with the community (Kampmark, p. 355). In fact, Queensland Attorney-General Denver Beanland’s 1998 request to appeal Salò’s R18+ classification was made on the basis that the new classification review board was known to be “full of normal people, as opposed to film critics” and the out-of-touch academics that had previously allowed for the film’s release (Lane). The six members of the 1998 board were supposedly more representative of “reasonable” Australian adults who, like Beanland, would be deeply offended and disgusted by the kinds of gratuitous violence and abhorrent sexual activity portrayed in Salò. However, as Michael Ramaraj Dunstan argues in “Australia’s National Classification System for Publications, Films and Computer Games: Its Operation and Potential Susceptibility to Political Influence in Classification Decisions,” the favouring of “ordinary citizens” over “experts” was merely a strategy that allowed for political manipulation (p. 149). As the criteria for selecting “ordinary citizens” is far less objective than that for selecting “experts,” who require professional qualifications or industry experience (Dunstan, p. 149), Howard’s position that current board members were out-of-touch with the community gave his administration the ability to change appointees for political reasons (Dunstan, p. 150). Despite claims that the classification boards would be more representative of the Australian public, in actuality the classifiers were replaced with those willing to support and enforce Howard’s conservative censorship agenda.

During Howard’s time in office, the classification boards were reformulated with the Liberal Party supplying the Office of Film and Literature Classification with a “more conservative panel of censors” (Maddox, p. 76). In “Moral Cleansers Past Their Used-by Date,” political commentator Ross Fitzgerald describes how Howard “carefully installed puritans” in key positions throughout the government, leaving Australia with a “wowserish administration” ill-fitted to deal with modern society. Others such as Binoy Kampmark have also used the term “wowser” to describe the conservativism of the Australian media landscape during the Howard years. According to Irene Graham, editor of the censorship and freedom of speech website libertus.net, “a remarkable number of appointments made since 1999 indicated positions on the Classification Boards were regarded as jobs for mates of Commonwealth Liberal Party Government politicians and/or the Liberal Party generally.” Graham is not the only person to have made this claim. In 2007, then Australian Labor Party Shadow Minister for Homeland Security, Arch Bevis argued:

The chief problem facing Australia’s classification regime these days is simply the fact that the government has spent the past 11 years making sure that, instead of community representation, Liberal Party mates are more than well represented on that Classification Review Board . . . In other words, we have a board that, in large part, is representative not of the community at large but of a narrow political ideology represented in the Liberal Party. How can the Australian community have confidence in the classification watchdog when more than half of its members are representative of such a narrow constituency?

Members of the classification boards who had connections with Prime Minister John Howard and the Liberal Party include: Donald McDonald who served as the Director of the Classification Board and was “widely reported to be a close friend” of John Howard (Graham); Trevor Griffin who was Attorney-General in the South Australia Liberal Party Government and “during which time . . . demonstrated the traits of an arch conservative” (Graham); former Convenor of the Review Board, Maureen Shelley, a Liberal Party candidate in the 1998 Federal election and a Councillor and former Deputy Mayor of Ku-ring-gai Council; former Review Board member, Rob Shilkin, Liberal Party member; and former member of the Review Board, Gillian Groom, wife of Ray Groom, Liberal Premier of Tasmania from 1992-1996.

The number of Liberal Party members or associates appointed to the Classification Board and Classification Review Board during the Howard era reveals that they were far from representative of the Australian community. Given Howard’s connection to the religious right, his promise to tighten film and video censorship in Australia and the conservative politics of the Liberal Government more generally, this goes some way to explaining why Salò was refused classification after five years of having been released. The 1998 re-banning of Salò was a victory for Howard and the repressive Christian right. While the ban placed further restrictions on the civil liberties of Australian adults, conservatives triumphed at the film’s censorship.

Banned (Again): Overturning Salò’s R18+ Classification

The re-submission of Salò to the Classification Review Board in February 1998 came about at the request of then Queensland Attorney-General and Minister for Justice, Denver Beanland. Beanland had previously sought a review of the film a year earlier, after the Classification Board reclassified Salò R18+ in June 1997 but was unsuccessful in having the classification overturned. Adamant that Salò should be refused classification in Australia, Beanland urged then Commonwealth Attorney-General Daryl Williams to apply for a review of the film. This time the appeal was successful and the Review Board revoked Salò’s R18+ classification, classifying the film RC (refused classification). [2] Despite having been released and screened in Australia for the previous five years, Salò was once again banned. Although Beanland was apparently a firm believer that adults are mature enough to choose what they watch, he was also of the view that Salò’s “outright brutality and pedophilia” was not acceptable and described it as a “depraved and disgusting film that should never have received an R rating in the first place” (qtd. in Marr, 1999, p. 194). The Review Board clearly agreed with this sentiment. This section looks closely at the 1998 Classification Review Board’s report on Salò, detailing the reasons and rationale behind their ultimate decision to refuse classification of the film and thereby re-ban it.

Offensive and Cruel: Representing Sexual Violence and Fetishes

The most significant factors leading to the banning of Salò by the 1998 Review Board were the film’s depictions of cruelty and its offensive images of sexual violence. While the Review Board agreed with the Classification Board that much of Salò could be accommodated by an R18+ classification (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p. 146), the two boards strongly differed in their interpretation of what constitutes cruelty. Whereas the majority of the Classification Board believed that the scenes in question portrayed acts of violence that could appropriately be accommodated by an R18+ classification, the majority of the Review Board believed otherwise. Rather, they held that many of the scenes in Salò not only depicted violence and sexual violence but went one step further depicting cruelty and persons in a demeaning manner (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p. 147). The Review Board stated that their understanding was that “violence is usually defined as physical force inflicted with the intent to seriously hurt or kill, or the outcome of such. Cruelty, on the other hand, involves delight in the infliction of, or indifference to another’s pain” (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p. 147). Moreover, they found that in addition to depicting acts of cruelty, the scenes were of high impact and, crucially, they were offensive. As stated in the Guidelines, offensive material is defined as that which “causes outrage or extreme disgust” (p. 14). The following scenes were identified by the Review Board as depicting cruelty, of high impact and offensive:

31 mins: prolonged scene of boy being whipped

32 mins: girl eats cake with nails in it, screams, and blood runs from mouth

63 mins: girl forced to crawl across the floor and eat faeces

71-73mins: all in the dining room are forced to eat faeces as meal

102 mins: girls tied up in a vat of filth (faeces and urine)

105-111 mins:

>boy has penis burned with candle

>girl has nipple burned with candle

>boy has tongue tip cut off

>girl endures forced anal sex and is hanged

>boy has eye gouged out

>girl endures forced anal sex

>girl is scalped

>girl and others are whipped

>boy is branded with branding iron

(Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p. 147)

The Review Board also determined that several scenes in Salò depicted sexual violence and fetishes in an offensive way. [3] The following scenes were held to contain offensive depictions of sexual violence or sexual violence accompanied with fetish activity:

29 mins: girl forced to urinate on face of male sexual aggressor

49-52 mins: girl forced, with screams, on to all fours, for extended (with some scene cutting) anal intercourse with soldier

62 mins: girl cries, is stripped under extreme duress, with the dialogue “the little slut’s howling is the most exciting thing in my life”

77 mins: girl forced to urinate on face and into mouth

(Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p. 148)

In their findings on Salò, the Review Board further argued that many of the scenes in the film were both sexually violent and cruel. They maintained that these depictions of sexual violence and fetishism were demeaning to the young people involved, and thus, were even more offensive and unclassifiable within the scope of the R18+ category (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p.148). The representation of young men and women being forced to eat faeces and urinate on the faces of their oppressors, for example, were found to debase in a sexual nature these young characters. While depictions of sexual abuse, degradation and other violent acts may be permitted within the R18+ classification, a film must not appear to approve of or encourage the immoral sexual behaviour and, importantly, the material must be justified by context. Although in this case the Review Board did not dispute that Salò was anti-violence and therefore not condoning of the acts being portrayed, they nevertheless held that the cruelty being inflicted on the victims was not sufficiently contextualised. In their opinion these sexual acts were offensive because they were not justified by context and as such were excessive and gratuitous. Moreover, they found the sexual imagery in Salò exceeded the boundaries of social and moral acceptability, arguing that the film would likely trigger feelings of “outrage” or “extreme disgust” in reasonable viewers. Therefore, the film was deemed too offensive, even for adult audiences.

The Review Board’s position that Pasolini fails to provide context for the inclusion of such material is curious given so many others have defended the film’s violent and sadistic representations on the grounds that Salò is intended as a metaphorical statement against fascism and absolute power. Father Michael Elligate, who was on the 1993 Board of Review, has remarked that Salò is “perhaps the most powerful modern critique of the whole issue of fascism and the totalitarian state” (qtd. in Marr, “Art vs Innocence”). The images of sexual violence, torture and sadism in Salò are prolonged, disturbing and shocking but integral to Pasolini’s purpose and are neither erotic nor titillating (Milliken, p. 75). As Stephen Tropiano has said of Salò, there is “nothing remotely erotic about all this debauchery” (p. 216). These sexual acts are “presented as brutal, sudden eruptions that occur without modulation, seduction, or the traditional elements of building cinematic tension” (Salvage, p. 92). They lack elements of cinematic foreplay or the “strip tease” which is often what makes portrayals of sexuality erotic (Salvage, p. 92). In other words, Salò does not arouse the spectator because unlike Hollywood depictions of sex it lacks elements of seduction. Rather the sexual imagery in Salò is what Tanya Krzywinska calls political bondage, domination and sado-masochism. She explains in Sex and the Cinema that films characterised in this way “use BDSM imagery and themes to comment on broader power relations or politics. [They] actively set out to disturb the erotic gaze by aligning sex and desire with . . . power” (p. 196). In Pasolini’s own words, sadism is used in the film as “a sexual metaphor for class struggle and power politics” (Pasolini, p. 39). His intentions are clear in this comment made to Bachmann in an interview during the filming of Salò:

My film is planned as a sexual metaphor, which symbolizes, in a visionary way, the relationship between exploiter and exploited. In sadism and in power politics human beings become objects. That similarity is the ideological basis of the film . . . there you have two basic dimensions: the political and the sexual. (p. 40)

Elsewhere the film’s depraved and sadistic imagery has also been widely interpreted as an attack on corrupt, bourgeois capitalist society (Tropiano, p. 216). Even the minority of the Review Board disagreed with the majority’s claim that these images were not sufficiently contextualised. In contrast, they argued that these depictions were not gratuitous, excessively prolonged or detailed and were well within the context of the storyline (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p.150). For the minority of the board, like other supporters of Pasolini’s work, Salò is a “powerfully realised political statement on the violation of innocence and freedom” (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p.151). In response to the majority’s claims regarding the audience’s likely reaction to such content, the minority argued that although the film may cause outrage or extreme disgust in many people, it would not have this effect on most people electing to see the film (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò p.150). Therefore, the minority concluded that Salò was not offensive under the intended definition of offensiveness outlined in the Code and should be given an R18+ classification on the grounds of its artistic merit. However, the majority members did not agree. As will be shown below, Salò’s artistic merit was not enough to protect it from allegations of offensiveness or secure the film a classification.

A Serious Work of Art or Indefensible Cinema?

Artistic merit was of vital importance to the 1993 Board of Review in granting Salò an R18+ classification. They considered the film to be “a serious work of art pursuing a serious political purpose” (Connonlly qtd. in Marr, “Art vs Innocence”), and the depictions of degradation and abuse at the hands of powerful authority figures integral to the film’s intentions. In recalling the decision to classify Salò R18+, Deputy Convener of the 1993 Film and Literature Board of Review, Keith Connolly explains that although members of the board were shaken up by the film, they understood that Pasolini was a great filmmaker and that “serious film-goers shouldn’t be deprived of the opportunity to see his work” (qtd. in Marr, “Art vs Innocence”).

In 1998 the new Review Board, as required by Section 11 of the 1995 Classification Act, also considered Salò’s artistic and educational merit before making their final decision. In their report, the Review Board acknowledges that Salò was Pasolini’s last film and therefore vital to any study of the auteur’s life work. However, this consideration was ultimately outweighed by the “offensiveness” of the material being depicted. While a year earlier the Classification Board had held that Salò was “of considerable artistic merit” and the depictions throughout justified by the “context of a defensible story line” (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò, p.146), the Review Board, somewhat dismissively, stated that “the film is said to have been intended as a serious work of art” (emphasis added) but its intention to make a statement about the abuses of power could have been achieved “without the overall depth of offensiveness” (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò p.149). Moreover, as discussed above, they did not believe that the film had effectively made any connections between fascism and the horrifying abuses of power being portrayed. It was therefore the opinion of the Review Board that the frequent depictions of young people forcibly participating in activities involving cruelty and sexual violence with offensive fetishes could not be justified by context and the defence that the film is intended as a serious work of art.

The Review Board’s decision to ban Salò because of its perceived offensiveness is indicative of a classification system which consistently rewards conformity and reinforces mainstream Hollywood cinema, while placing limits on artistic expression and freedom of choice. The labelling of imagery as offensive in this way is often used to justify censorship in Australia, particularly if the material is controversial and of a sexual nature as in the case of Salò. While artistic merit is something that the boards are required to consider when making a classification decision, as was pointed out earlier, it is no longer a defence to obscenity, or in today’s language offensiveness. It is not enough for a film to simply be labelled art. Instead, the classification boards must decide whether the artistic value of a film warrants its classification, or, if the offensiveness of the material outweighs any artistic merit the film is said to have. Indeed Helen Vnuk, in Snatched: Sex and Censorship in Australia, asks whether there is a sliding scale which measures how much artistic merit a film has, and whether a film which has more artistic merit can get away with showing more gratuitous and exploitative scenes than a film with less artistic value (p. 209). Vnuk raises an interesting point. However, while some films, such as Catherine Breillat’s Romance (1999) and Michael Winterbottom’s 9 Songs (2004) have gotten away with depicting more gratuitous and exploitative sexual imagery based on the director’s prestige and the film’s perceived artistic merit, there also seems to exist a somewhat subjective boundary of acceptability where artistic merit alone will not save a film from censorship. In the case of Salò, Pasolini’s international acclaim as a filmmaker and the intrinsic artistic value of his work were not enough to defend the film against charges of offensiveness and prevent the Review Board from banning it.

The statements made by the Review Board in relation to Salò show that in certain circumstances images of sexual violence and fetishes may be permitted but only if they occur infrequently, are not represented in a way that is seen as approving or encouraging of the behaviour and, most importantly, are explicitly justified by context. If these elements are in doubt, that is, if the sexual material is seen as excessive, cruel or not clearly contextualised, then these images are at risk of being characterised as gratuitous. The interpretation of Salò’s sexual violence as unjustifiable and offensive is what led to the film being refused classification. Had the Review Board accepted that these sadistic depictions were integral to the narrative and Pasolini’s intended metaphorical statement about fascism and the abuses of power, an R18+ classification could have just as easily been given on the basis of the film’s artistic merit. However, in an era marked by social and political conservatism and a lack of appreciation for the arts, artistic merit clearly does not hold much weight. Even though Salò was seen to exist within the realm of art, the Review Board still prohibited its release by labelling the film offensive to the reasonable adult of whom they are supposedly representative of.

Youthfulness of the Characters

Despite claims to the contrary, the age of the young characters in Salò was a significant factor in the Review Board’s decision to ban the film. David Marr believes that it was the youthfulness of Pasolini’s actors that would “eventually bring Salò undone” (Marr, 1999, p. 201). While the 1993 board barely mentioned the age of the young people being depicted, the reformulated Review Board paid careful attention to whether the young people looked as though they could be under the age of 16 (Marr, 1999, p. 201). Five years earlier, when he sat on the review board, Father Elligate stated that Pasolini used young people, not children: “Whatever this was, it’s not pedophilia” (Elligate, qtd. in Marr, 1999, p. 201). However, the new classification guidelines and code, introduced in 1995, specifically instruct that films should be refused classification if they “depict in a way that is likely to cause offence to a reasonable adult a person who is, or who looks like, a child under 16.” Marr explains that “[o]nce the film was declared an artistic failure, the question of the age of the actors became crucial” (1999, p. 204).

In their report, the Review Board considered the age of the young people being portrayed and asserted that some of the characters in Salò could have been under the age of 16 (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò p. 147). They suggest that this is further emphasised by the scenes in which the characters are dressed as school children (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò p. 147). [4] However, the Review Board qualify their position later in their findings when they state that the offensiveness of Salò was increased by the “involvement of young people who, if not clearly under 16 years, nevertheless looked like persons under the age of 18” (p. 148). Given that the code was not amended to read 18 until 2005, the Review Board appears to be implementing their own regulations here, rather than making determinations based on the guidelines before them. Nevertheless, the majority of the Review Board believed that the apparent youth of some of the characters should be considered given the portrayal of the sexual abuse of young people throughout the film.

While the Review Board stated that the youthfulness of the characters alone could not warrant an RC classification, they did believe that the age of the young people being abused was important in considering the overall offensiveness of the film (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò pp. 147-148). The Review Board clearly used the youthful appearance of the characters to further justify their decision to ban Salò. In stating that the actors “nevertheless looked under the age of 18,” the age of legal adulthood in Australia, the Review Board was implying that the characters were still represented as children. Even the terminology used by the Review Board evokes images of childhood. For example, the terms “boy” and “girl” are used rather than male and female when describing the victims in their report. This appears to be a tactic to infantilise the young people being depicted. The Review Board could then argue that any reasonable adult would find the depiction of children in a demeaning manner offensive. By emphasising the youth of the young characters, the Review Board sensationalised Salò into a paedophilic film about children being abused rather than a film about fascism and the corrupting effects of absolute power (Elligate in Marr, 1999, p. 204).

Adults should be able to see what they want, unless . . .

One of the fundamental principles of Australia’s National Classification Code is that “adults should be able to read, hear, see and play what they want.” [5] The Review Board acknowledges in their report on Salò that they are required to consider this guiding principle. However, they explain that their decision must also take into account community concerns around representations of sexual violence (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò p.149). The Review Board claimed that Salò’s depictions of cruelty, sexual violence and fetishes would “offend against the standards of morality, decency and propriety generally accepted by the reasonable adult.” This is what ultimately allowed them to overturn the R18+ classification that Salò had maintained for the previous five years and once again ban the film.

Historically, community concerns have often been used as a convenient way to override all other principles regarding film classification, including those related to consumer freedoms. The hypocrisy that lies at the core of our classification system is that it vows to ensure that all adults “be able to read, hear, see and play what they want,” while at the same time restricting that very freedom by banning certain materials from adult audiences. Margaret Pomeranz, respected film critic in Australia and member of Watch on Censorship, has said of Salò’s ban: “I can’t stand the idea of this nanny state, which says, ‘We’re not going to let you see something, it’s too revolting.’ This is outrageous” (qtd. in Browne). Terry Lane calls the Review Board’s decision to ban the film “a triumph of stupidity and anti-intellectualism.” He believes that it “marks a regression into the infantilism and paternalism of the past” (Lane). In contemporary liberal societies, such as Australia, words like “censorship” are actively avoided in favour of less authoritarian notions like “classification.” However, in practice, the system still acts to prevent both children and adults alike from accessing certain content. Australia’s classification legislation has been created to allow for the prohibition of films categorised as immoral, gratuitous or offensive and thereby restricts adult audiences from exploring different ideas and making their own moral judgments.

When the Review Board bans a film, as it did in the case of Salò, it suggests that Australian adults are incapable of making a rational choice about whether or not a film is appropriate for them to see, or that they are not intelligent enough to understand the material before them. Clearly the right of adults to see what they want was not at the forefront of the Review Board’s classification decision. Despite allowing for the possibility of Salò’s release, the Review Board was able to subjectively apply the Act, Code and Guidelines to ban a film that in their opinion lacked artistic value, was offensive and immoral.

The Saga Continues

Salò’s censorship saga continued when in 2008 a modified version of the film was submitted to the Classification Board for DVD release. Ten years had now passed since its 1998 ban; still, the Classification Board upheld the film’s RC classification stating:

while the film purports to have some degree of artistic merit and justifiable context (taking into consideration the notoriety of the director, the narrative structure of the Marquis De Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom and the portrait of human degradation which serves as an apparent metaphor for fascism), the context does not sufficiently justify the content of the film to the extent that it can be accommodated at the R18+ classification. (Classification Board and Classification Review Board Annual Reports 2008–2009, p. 50)

The reasoning behind the Classification Board’s decision echoed that of the 1998 Review Board. The board maintained that the film’s depictions of violence, child sexual abuse, fetishes and cruelty were “expressly prohibited under the Classification Guidelines” (Classification Board and Classification Review Board Annual Reports 2008–2009, p. 50). In justifying their decision, the board emphasised the inclusion of offensive and abhorrent fetishes, the offensive and exploitative depiction of characters who are, or appear to be, under the age of 18, and described Salò’s violence as of very high impact, excessively prolonged, frequent and detailed (Classification Board and Classification Review Board Annual Reports 2008–2009, p. 50). This was another setback for distributors and others fighting to have Pasolini’s final film released in Australia. However, the story does not end here; this was not the last time Salò would find itself before Australia’s classification boards.

Conclusion

. . . in a world fearful of ideas, the biggest threat to an open, democratic society is not the portrayal of violence and evil, but the zipping up of the lips that want to express ideas – some of which take the form of perverse stories. (Mills The Money Shot pp. 84-85)

It is no accident that the films which have been banned or censored in Australia have been those valued by both political and sexual libertarians (Mills, 2001, p. 117). As a film which defies the codes and conventions of dominant and acceptable representation, Salò was always going to find itself subject to scrutiny and detest. Naturally some audiences were shocked and even offended by the film but as Janet Strickland, Chief Censor 1979-1986, asks “If we have nothing that makes us feel shocked, how do we know what our value system is?” (qtd. in Guilliatt and Casimir) Controversial filmmakers like Pasolini are important as they make sense of the violence and corruption that exists in the world. These feelings of shock and disgust we experience when watching a film like Salò remind us of our own moral compass and reinforces the value system we hold true as a society. Those responsible for banning films containing more graphic and provocative depictions of sex and violence should be wary of the effects such censorship may have. Mills explains, “[c]ultural and political isolation is ensured as we are left ignorant of how other societies and their cultures do or don’t make sense of inequality, degradation, exploitation and power struggles when moving images are sanitised or banned” (Mills, 2001, p. 93). Simply put, “the results of suppressing screen violence may be infinitely worse than anything its depiction might do” (Mills, 2001, p. 85). Representations of violence, including sexual violence and other deplorable acts of human cruelty, help us to understand real violence that occurs in the world around us. When filmmakers like Pasolini use violent imagery in their films, it is often to make a statement about the human condition. When that screen violence is then banned, we are forbidden the images we need in order to make sense of our humanity and the inhumanity of others. Nevertheless, what this article has shown is that our classification system is not in place to protect such liberties. The 1998 Classification Review Board was uninterested in Salò’s artistic, political or social value; the film was refused classification because it did not reflect the board’s new conservative morality and right-wing agenda.

Art is subjective and so too is the value one places on art. While the 1998 Review Board and 2008 Classification Board could have exempt Salò from being refused classification based on its widely acknowledged artistic merit, the decision in both instances to refuse the film a classification reflects a different imperative. The case of Salò highlights a key issue with Australian classification, that is, that it allows for the censorship of content based on conservative notions of decency, morality and offensiveness. While the first principle of the National Classification Code states that “adults should be able to read, hear, see and play what they want,” this is not the priority of the classification boards. Rather Salò’s ban suggests that the boards’ obligation lies not in ensuring this fundamental principle is upheld but rather in fulfilling their role in “protecting” the community. In order to justify censoring material that they disapprove of, the boards may simply argue that their decision reflects “community concerns” and that it ensures “everybody [is] protected from exposure to unsolicited material that they find offensive.” In the end these latter principles will always triumph the right of adults to watch what they want.

In May 2010, Salò once again found itself before the Review Board and was finally released on DVD for the first time in Australia. On the one hand, the decision of the Review Board to now allow Salò to be released with an R18+ classification was unexpected. On the other hand, given the film’s tumultuous classification history in Australia, and the inconsistent and often contradictory ways in which the boards apply the guidelines and code, this backflip is hardly surprising. The 2010 Review Board classified the uncut DVD version of the film R18+ with the consumer advice “Scenes of torture and degradation, sexual violence and nudity” (Classification Review Board Salò). The two-disk DVD includes three hours of additional documentary material and behind-the-scenes footage. It is this extra material, said to provide the audience with greater context, that made Salò’s release possible. The Review Board states in its report that the additional footage contained in the DVD “facilitated wider consideration of the historical, political and cultural context of the film, and this would mitigate the level of potential community offence . . .” (p. 7). There is no guarantee that anyone who buys Salò on DVD will watch the extensive additional footage and so it is curious that this had such a bearing on the Review Board’s decision to allow for the release of the film. Interestingly, the Review Board also determined that “the impact of Salò, now 35 years old, is reduced by its age, its dated and sometimes technically unconvincing visual effects and construction of the film’s narrative through mostly obscured long or extreme long shot visuals and editing techniques” (p. 7). That Salò’s age was not a major consideration for the Classification Board just two years earlier is telling of how arbitrarily classification decisions are made in this country. Salò’s censorship battle is unusual, unprecedented and perhaps not over but more importantly it is noteworthy as it demonstrates significant problems with Australia’s classification system. There are discrepancies that exist within and between the boards and inconsistencies in how the guidelines and code are interpreted and applied when making classification decisions. So, after having been banned, released and banned again, Australian adults are free to watch Salò . . . for the time being anyway.

NOTES

[1] With the introduction of the R18+ computer game classification in 2013, this was later modified to “adults should be able to read, hear, see and play what they want.”

[2] If a film is refused classification it cannot be legally sold, distributed, advertised or imported in Australia as it is seen to fall outside generally accepted community standards.

[3] The Guidelines define sexual violence as “[s]exual assault or aggression, in which the victim does not consent” and a fetish as an “object, an action or a non-sexual part of the body which gives sexual gratification.”

[4] It is interesting to note here that the Classification Board had previously found that the actors “did not” appear to be under 16 (Reports of the Classification Review Board Salò p. 146).

[5] Note that in 1998 the Code did not include the word “play” as the R18+ classification for video games had not yet been introduced.

REFERENCES

9 Songs. Dir. Michael Winterbottom. Perf. Kieran O’Brien and Margo Stilley. Accent, 2004.

A Serbian Film. Dir. Srđan Spasojević. Perf. Srđan Todorović and Sergej Trifunović. Jinga, 2010

Baise-Moi. Dir. Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh Thi. Perf. Karen Lancaume and Raffa‘la Anderson. Canal+, 2000.

Rachel Browne, “Sadistic Sex Movie Ban ‘attacks art expression’.” Sydney Morning Herald, 20 July 2008 <http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2008/07/19/ 1216163226456 .html>.

Classification (Publications, Films and Computer Games) Act 1995. Commonwealth of Australia.

Classification Board and Classification Review Board. Reports of the Classification Review Board. Salo o le 120 Giornate di Sodoma (Pasolini’s 120 Days of Sodom). Appendix II. Classification Board and Classification Review Board Annual Report 1997-1998. Sydney, NSW. Pp. 144-151.

—. Classification Board and Classification Review Board Annual Reports 2008-2009. Attorney-General’s Department. Surry Hills, NSW.

—. Classification Review Board. Salo o le 120 Giornate di Sodoma (Salo). Surry Hills, NSW. 4 and 5 May 2010. Classification Website. 20 Oct. 2010 <http://www.classification.gov.au/>.

“Deliver Us From Evil.” Four Corners. ABC. 8 May 2000. Transcript. 15 June 2009 <http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/stories/s124743.htm>.

Michael Ramaraj Dunstan, “Australia’s National Classification System for Publications, Films and Computer Games: Its Operation and Potential Susceptibility to Political Influence in Classification Decisions.” Federal Law Review 37 (2009): pp. 133-57.

Festival de Cannes. 2011. Festival de Cannes. 21 Mar. 2011 <http:// www.festival-cannes.org/>.

Ross Fitzgerald, “Moral Cleansers Past Their Used-by Date.” Australian 7 Jan. 2008. 23 Mar. 2011 <http://www.theaustralian.com.au>

Irene Graham, “Classification (Censorship) Boards.” Libertus.net. Ed. Irene Graham. 28 Feb. 2010. 26 Apr. 2011 <http://libertus.net/censor/aboutcboards.html>.

Guidelines for the Classification of Films and Computer Games 2003. Commonwealth of Australia.

Guidelines for the Classification of Films and Computer Games 2005. Commonwealth of Australia.

Guidelines for the Classification of Films and Computer Games 2012. Commonwealth of Australia.

Guidelines for the Classification of Films and Videotapes 1996. Commonwealth of Australia.

Guidelines for the Classification of Films and Videotapes 1999. Commonwealth of Australia.

Richard Guilliatt and Jon Casimir, “The Return of the Wowsers.” Sydney Morning Herald 6 July 1996.

Gary Indiana, Salò or The 120 days of Sodom. London: BFI, 2000.

Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin. 2011. Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin. 21 Mar. 2011 <http://www.berlinale.de/en/HomePage.html>.

Kampmark, Binoy. “A Wowseristic Affair: History and Politics Behind the Banning of Ken Park, Baise-Moi and Other Like Depravities.” Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 20.3 (2006): pp. 345-61.

Ken Park. Dir. Larry Clark and Edward Lachman. Perf. Adam Chubbuck, James Bullard, Stephen Jasso, Tiffany Limos and James Ranson. Busy Bee Productions, 2002.

Tanya Krzywinska, Sex and the Cinema. London: Wallflower, 2006.

La Biennale di Venezia. 2010. la Biennale di Venezia. 21 Mar. 2011 <http:// www.labiennale.org/>.

Terry Lane, “Salo is Rebanned.” Sunday Age 1 Mar. 1998.

Marion Maddox, God Under Howard: The Rise of the Religious Right in Australian Politics, Crows Nest, Australia: Allen and Unwin, 2005.

Robert Mallett, “Film Review – Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom) directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini.” Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 2.1 (2001): pp. 84-87. Informaworld. 17 Aug. 2009 <http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/714005436>.

David Marr, “Art vs Innocence.” Sydney Morning Herald 25 May 1998. 02 Sept. 2009 <http://www.web.archive.org/web/19991113143051/http://www.smh.com.au/news/9805/25/features/features1.html>.

David Marr, The High Price of Heaven. St. Leonards, Australia: Allen and Unwin, 1999.

Sue Milliken, “Violence in the Cinema.” Address. The Sydney Institute, NSW. 19 July 1994. Sydney Papers 6.4 (1994): pp. 70-79.

Jane Mills, The Money Shot: Cinema, Sin and Censorship. Media.culture series. Sydney, Austral: Pluto P. 2001.

Jane Mills, “Film Censorship in Australia.” May 2000. Watch on Censorship. 15 May 2001. Watch on Censorship Inc. 19 Apr. 2011 <http:www.watchoncensorship.asn.au/ guides/20000518.html>.

Bill Mousoulis, “In the Extreme: Pasolini’s Salò.” Senses of Cinema 4 (2000). 31 Aug. 2009 <http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/4/salo.html>.

National Classification Code 1995. Commonwealth of Australia.

National Classification Code 2005. Commonwealth of Australia.

National Classification Code 2005. Explanatory Statement. Issued by the Authority of the Attorney-General. Commonwealth of Australia.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, Interview with Gideon Bachmann. “Pasolini on Sade: An interview during the filming of ‘The 120 Days of Sodom’.” Film Quarterly 29.2 (1975-1976): pp. 39-45. JSTOR. 17 Aug. 2009 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1211747>.

Romance. Dir. Catherine Breillat. Perf. Caroline Ducey and Sagamore Stévenin. 1999. DVD. Madman, 1999.

Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom. Dir. Pier Paolo Pasolini. Perf. Paolo Bonacelli, Giorgio Umberto Paolo Quintavalle Cataldi and Aldo Valletti, 1975. Shock, 2010.

David Salvage, “A Psychoanalytic Consideration of Pasolini’s Salò.” Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry 33.1 (2005): pp. 83-96.

Stephen Tropiano, Obscene, Indecent, Immoral, and Offensive: 100+ Years of Censored, Banned and Controversial Films. New York: Limelight Editions, 2009.

Helen Vnuk, Snatched: Sex and Censorship in Australia. Milsons Point, Austral: Vintage, 2003.

Watch on Censorship. 15 May 2001. Watch on Censorship Inc. 24 Jan. 2011 <http:// www.watchoncensorship.asn.au/>.