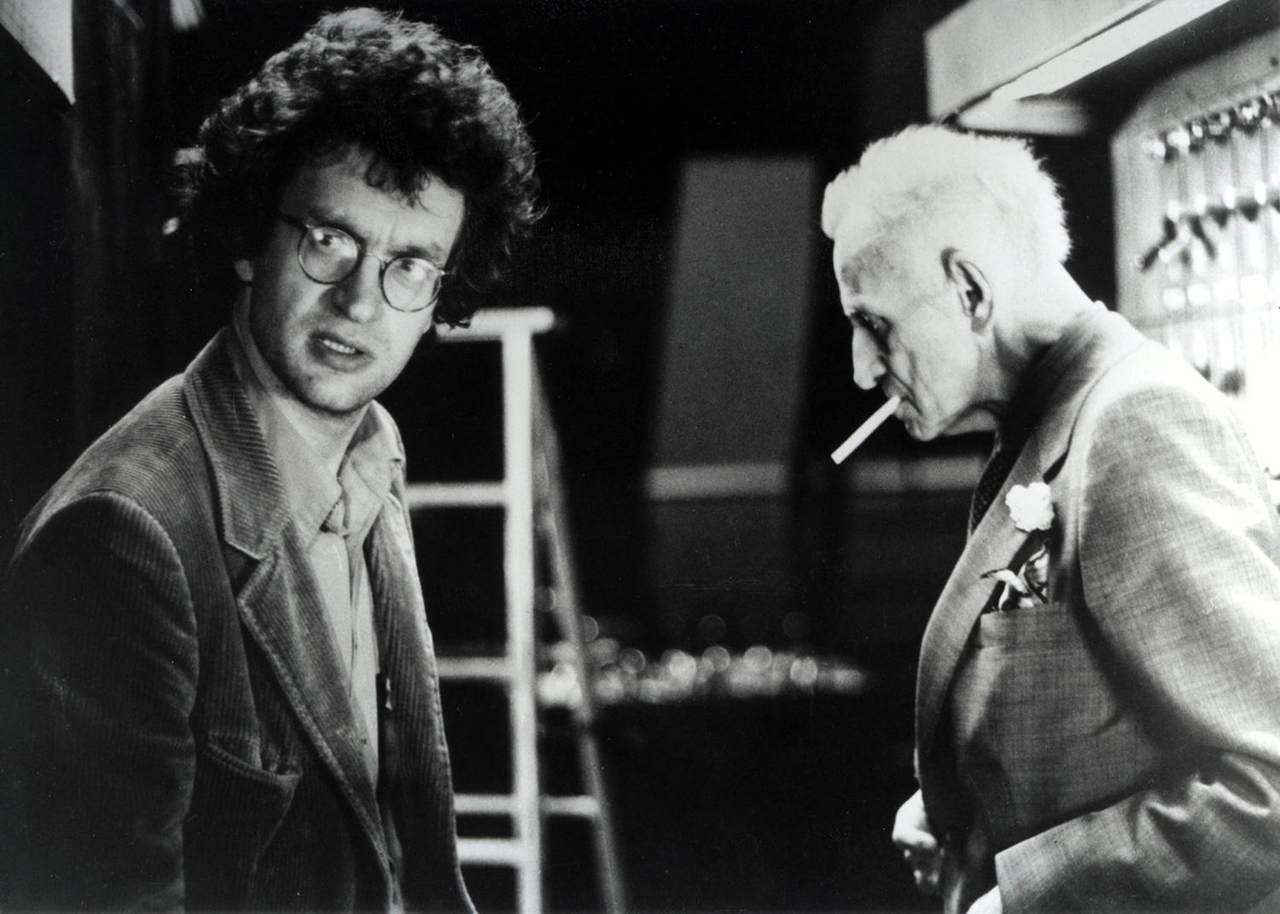

In Wim Wenders’ The American Friend, actor-director Dennis Hopper kills off filmmaker Sam Fuller (star of Hopper’s then seemingly last movie, The Last Movie, about a filmmaker making his last movie). Hopper’s character is a shady middleman art dealer caught between a dead artist who isn’t really dead (portrayed by director Nicholas Ray) and a dying art restorer who isn’t really dying (Bruno Ganz) – but dies anyway. In Lightning over Water, Wenders “collaborates” on- and offscreen with a dying Nicholas Ray in the latter’s last movie, about a dying filmmaker making his last movie, except that Ray dies before his – or perhaps only the film’s – time. In Wenders’ The State of Things, director Patrick Bauchau plays a German director whose first Hollywood film literally proves to be the death of him. Tokyo-Ga, Wenders’ docu-exploration of the city, soon turns into a panegyric pilgrimage tracing the life, films, times, and shrines of the late Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. In Room 666, Wenders’ filmed questionnaire on the state of the art, a succession of live filmmakers drop by Wenders’ deserted hotel room to file monologues on the death of cinema – and the film poetically acknowledges that one of them, R.W. Fassbinder, had died by the time it was edited.

This morbid self-referential maze is further infolded by the fact that Hopper’s Easy Rider was the celebrated Sixties version of the road movie, of which Ray’s 1948 They Live by Night might stand as the classic prototype, and that Wenders’ production company was called Road Movie – not too surprising since most of his films are road movies. All of which points toward a textbook case of what some literary and film critics have dubbed the Anxiety of Influence. Loosely defined, the term refers to a quasi-Oedipal self-consciousness on the part of artists toward their seminal predecessors, and their various attempts to deal with these overshadowing progenitors.

The unmistakable figure of Robert Mitchum strides across a rodeo arena, hitches a ride on a truck, and roots around the Old Homestead, finding under the porch the comic-books hoard of childhood. This sequence from Nicholas Ray’s The Lusty Men (1952) – compositionally, thematically, and otherwise very very like several scenes in Wenders’ Kings of the Road – appears in Lightning over Water. And indeed, Lightning over Water is nothing if not a psychodrama of anxiety of influence. Is Nicholas Ray, Wenders asks himself in the voice-over soliloquy that rhymes the film, his father-figure? Is Wenders killing Ray off or keeping him alive? Is he helping Ray to make his last movie or exploiting his death to make his own? Has he come to praise or bury his king of the road?

It has always seemed a particularly niggardly, finger-pointing question, that of influence. And copying the old masters was ever a more-than-acceptable form of learning one’s craft. Orson Welles reportedly watched Stagecoach dozens of times to “figure out how to make a movie”; Richard Fleischer’s early works look like Diabelli variations on one or another ten-minute sequence of White Heat. But for a generation that served its apprenticeship watching rather than making films (or “directing” in the hothouse artificiality of film school), the question has become a very loaded one.

Of course the “anxiety” of influence needn’t involve any literal angst. Godard, like some demented chipmunk, cheerfully strewed his films with allusions, tips of the hat, and clips from many and sundry of his favorites. And Brian De Palma gleefully thumbs his nose at audience and critics alike in his flamboyantly shameless two-fisted raids on the archives (how many times can you remake Vertigo, the story of a woman who is and isn’t dead?).

The directors of the French New Wave were the first to systematically denaturalize the ongoing evolution of film vocabulary, to make conscious the process of influence (Rivette sitting down cast and crew of Duelle to watch Kiss Me Deadly, Robert Aldrich and A.I. Bezzerides’ telling placement of global paranoia in atomic perspective). But in critically reexamining their Hollywood origins, the French effected a very real liberation from their own whimsy-and literary-laden “cinema de papa” – and nobody forced them to throw out the Renoir-Becker progeny with the bathwater. Since the New Wave took place, not coincidentally, within a general reevaluation of the implications, ideologies, and contradictions of bourgeois artforms, and since postwar American film had, thanks to the likes of Ray, Fuller, and Aldrich, gone much further than any other in questioning its own values, they were quite simply in a position to enjoy their Hollywood cake and critique it too.

The situation of the New German Cinema filmmakers was in no way as fortunate. Beyond the infinitely negative ramifications of the Third Reich legacy loomed the 20-year wasteland of German film – Hitler having managed to empty the larder of all those who hadn’t already left for more lucrative or saner pastures. Unlike the Japanese, whose cultural isolationism kept their cinema functioning and intact, Germany was left with a sparse heritage, more disturbing than inspirational, in the form of Leni Riefenstahl. Compounding the problem, to the victors the spoils: America occupied the land and the screens, often with the recycled products of German émigrés. As succinctly stated by Hans Zischler in Kings of the Road -raising high his bottle of Johnny Walker – “the Yanks have colonialized our subconscious.”

Some cinéastes, like Werner Herzog, responded by mystifying their Germanity, going off the Teutonic deep end in full Wagnerian death-wish panoply. Others, like Reinhard Hauff or, in his own cockeyed way, Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, clothed the already melodramatic life-and-death struggle of the German Left with apposite remnants of misguided or merely doomed mythologies. In the Shakespearean mode, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, safely ensconced in sexual otherness, recorded the passing scene, self-destructing in life but never on film.

Indeed, the example of Fassbinder, with his self-avowed lifelong debt to Douglas Sirk (formerly Detlef Sierck), points up the paradox of German cinema. Far from shunning or mythologizing the past, Fassbinder was quick to realize that he was in a unique position to record three generations of history that had no cinematic record. And what better mentor for the Fifties transition from war to peace than the director of All That Heaven Allows and Imitation of Life? Germany, too, moved to the suburbs.

Which makes Wim Wenders something of an anomaly in German film. In willfully (and oh so politically) disassociating himself from politics, Wenders allied himself with his contemporary subconsciousness-occupiers – inheriting their hangups in the process. For the peculiar configuration that here goes under the name Anxiety of Influence is most truly at home in Hollywood.

The first to act out the new American film-disciple mentality was Peter Bogdanovich, wearing his aficionado heart on his sleeve as he scurried around interviewing his directorial idols, and bursting upon the box office with his updated version of a John Ford Western (The Last Picture Show). His subsequent attempts to resurrect dead forms and dead processes – screwball comedies (What ‘s Up, Doc?), musicals (At Long Last Love), small-screen black and white (Paper Moon), silents (Nickelodeon) – met with lessening enthusiasm.

Far more successful than Bogdanovich’s pious earnestness was Brian De Palma’s pubescent impudence as he threw in everything but the kitchen sink in Hitchcockian pyrotechnic overkill, not caring – or perhaps willing – that the films fall apart in the process. For those who preferred good taste to bad, John Carpenter offered a critically brilliant, somewhat empty filmed analysis of Howard Hawks in his out-of-Rio-Bravo-via-The-Thing study of besieged enclosure, Assault on Precinct 13. Even Carpenter’s less derivative flights of fancy took the form of nightmarish, oddly seductive ancestors come back from the grave to gobble up their descendants and play out their primal scenes (The Fog), or fiends that just won’t die returned to exorcise those scenes (Halloween).

Steven Spielberg, having converted to born-again optimism under Reagan, had to farm out his own revenant nightmares to Tobe Hooper and Joe Dante: dead Native Americans wreaking havoc on their graveyard desecrators in Poltergeist; cute E.T. knockoffs turned nasties in Gremlins – creatures out of a musty Chinese den of antiquity, not some shining techno-future. For the past, like murder, will out.

That it will out murderously is due at least in part to the American wunderkinds’ quite conscious choice, after the debacle of major-studio production in the late Sixties-early Seventies, to reinvent Hollywood rather than reinventing cinema. Spielberg, queried about the future of cinema in Room 666, could speak only of money – as Herzog, denying all angst, could speak only of angst.

In Wenders’ case, one has the feeling that spectres from the past were not initially cinematic. There’s a curiously ill-defined sense of ancestral guilt in his German films that never manages to fix or express itself. Rüdiger Vogler returns to his deserted childhood home in Kings of the Road only to be seized by an unaccountable rage, smashing windows in an exorcism that, though apparently cathartic, is never explained. His fellow traveler Hans Zischler also returns home to tell off his editor father about the way the latter treated his mother. But he holds him captive for a peroration that never comes, using the linotype to compose a mass-media Extra that the film fails to deliver.

In The Scarlet Letter (1973), a husband who is not a father and a father who is not a husband revolve around the mute figure of Hester Prynne, whose confused messages pass through a Cassandra-like surrogate in an atmosphere of vague machinations and unheard confessions. In Wrong Move, a 20th century Wilhelm Meister leaves his mother to latch onto a sexy teenager and her father, whose Nazi past causes our hero to try to kill him – except that the hero’s too detached to have any personal stake in it at all. In the same film, an uncle’s grief over the death of his wife leads him to commit suicide – except that he’s nobody’s uncle, only a chance stranger misremembered from a bad poet’s past.

Inarticulate messages to inarticulated figures; fathers dead in the war perhaps, or relations best left in the dark; ghosts that walk the ramparts without ever giving up their secrets. Wenders, too young to have played any part in Hitler’s Master Plan, can apparently neither assign nor assume this floating inherited guilt – except, of course, for the guilt of noninvolvement. Hence the odd displacements, the makeshift reconstructions by which one restores someone else to a family that can never be one’s own.

In Alice in the Cities, a writer takes a child, who’s been abandoned by her mother, over the river and through the woods in search of grandmother’s house. In Kings of the Road, a wandering projectionist-repairman picks up, befriends, carts around, and restores to society a demoralized psychologist-linguist who has just broken up with his wife. Dennis Hopper in The American Friend first exploits Bruno Ganz’s love for his son to involve him in a murky Mafia plot, then, swayed by his growing liking for the man, becomes himself involved in a murderous last-ditch attempt to save Ganz and return him to his family. In Hammett, the writer abandons his role of disinterested observer in an attempt to save his father-figure mentor, the unnamed protagonist of his stories and the man who has taught him all. And in Paris, Texas, a veritable orgy of familial salvage, Dean Stockwell reclaims brother Harry Dean Stanton from an autistic sleepwalk in the desert, only to have Stanton take off with his Stockwell-adopted son on a mission to save his lost wife and reconstitute a family in which he then declines to take any part.

In this confused atmosphere of aleatory knight-errantry, it’s not hard to understand Wenders’ kinship to Ray, past master of indirect salvation (to the point of autodestructing in a vain attempt to impose his vision of Christ on the Pontius Pilates of Hollywood). For beyond those all-too real and constantly derealized shadows of best-forgotten ancestors lurk the adoptive cinematic fathers, themselves engaged in fictional appeasements of class and racial violence.

Yet next to the unthinkable, unexpiable guilt of systematic genocide, what is an old woodsman’s slaughter of flamingos (Ray’s Wind across the Everglades), or a suburban schoolteacher’s cortisone-induced commandment to kill his son (Bigger Than Life), or the death of James Dean’s rival caught in the trappings of a jaydee chickee-run (Rebel without a Cause), or an Eskimo trapper caught in a white man’s riddle of justice (The Savage Innocents)? If Ray’s heroes are ultimately doomed to disjunction, death, or a tenuous happy-ever-after, the force of their passion and commitment, for all its limitations, begins to approach the vastly superior forces of personal demons and social inequity arrayed against it.

But for Wenders’ heroes, burnt out, beyond commitment and sometimes even curiosity, their desultory rescue jaunts seem far less callings to save others from their own or the world’s destructiveness, than passing-strange happenings in an otherwise figureless landscape – happenings that promise, for a time at least, to make up a story.

Stuck in an undifferentiated present tense where each day resembles another, on an undifferentiated odyssey among interchangeable landmarks (Dennis Hopper to his tape recorder in The American Friend: “I know less and less about who I am or who anybody else is. Even this river, this river reminds me of another river”), mired in an existential impassivity not unconnected to their sexual and emotional impotence, Wenders’ heroes are the obverse of Ray’s. But the observe of the same coin. For Ray violence is the fatal original sin, seductive in its action ethos, irresistible in its brute force and simplicity; for Wenders, to be the hero or villain of a story seems the impossible dream. Ray’s films are about the alienation of action, the failure of the ego, a frail center that cannot hold. (Poor rich kid Sal Mineo in Rebel, pursued by demons of his own, his parents’, and the LAPD’s making, dies for no particular reason in a blaze of light on the steps of a deserted planetarium, blind galaxies moving within.) Wenders’ films are about the alienation of passivity, the dispersion of the ego in a time and space outside narrativity.

In Wenders’ remarkable visualization of Peter Handke’s celebrated novel The Goalie’s Anxiety over the Penalty Kick (1972), a goalie (Artur Brauss), having let pass a point in a moment of distraction, suddenly checks out – of the game, the job, and life as it’s usually lived on this planet. Cut off from any particular order, sequence, or thing to do, his day-to-day existence takes on an almost hallucinatory clarity as moments, events, objects, strung together with no particular logic or urgency, lose their subjective dimension and become, at the same time, flat and arresting. His pickup of a movie box-office girl whom he follows home, beds, breakfasts with, and strangles (she plays with her belt, he plays with her belt, and then, suddenly, apparently unwilled by anyone or anything, it’s around her neck and she’s dead) has little more resonance than, say, his throwaway conversation with a package-laden matron on a bus.

Even the newspaper followups of the murder, anxiously then casually perused by the goalie, and the tantalizingly meager clues – a few dimes and quarters left at the scene of the crime from the goalie’s talismanic souvenirs-of-America hoard; more coins subsequently dropped into crevices and conversations in traditional “suspense motif” fashion – refuse to add up to a story. They come fleetingly into focus no longer, indeed less insistently, than the story of a missing deaf-mute boy found floating in the river. The goalie cannot appropriate people or events. Everything and nothing is a story. Everything and nothing is his story.

Goalie’s protagonist stays very sharply etched throughout, a dead stillness at the center of the frame, the enigma around which everything crystallizes. In Wenders’ second collaboration with Handke, the Goethe-derived Wrong Move (1975), the central character (Rudiger Vogler) acts as an ambulatory floogle factor, a half-assed identification principle who constantly throws the frame out of whack. Desperately seeking something to write about, our would-be novelist hero wanders through a Germany where adventures bloom in riotous profusion and mysterious figures beckon, ripe to unbosom their secrets. Yet he sees and learns absolutely nothing. Stumbling around in the dark, he can’t even manage to sleep with the right woman.

Wrong Move, in its jerky, restless futzing-around, traces a succession of neurotic missed opportunities that’s sporadically quite funny in its mock-Wagnerian romanticism: golden-haired movie queen Hanna Schygulla hanging out her train-compartment window, flashing lustrous promises to our hero on another track, while their two trains obligingly loop and glide under and around each other for improbably long minutes. Yet, perhaps because Wenders’ sense of humor is not his most developed faculty (no Skolimowski he), the less pathological his protagonist, the less objective and effective the rhythm of his disjunction. Wrong Move waffles between humor and bathos, its hero too close for comfort, too far for enlightenment.

That seems to be the problem with all Wenders films with a writer at the center. Alice in the Cities, Wrong Move, and Hammett alike suffer from a blurring of focal distance – an almost autobiographical fallacy, as if the director’s own anxiety about having to tell a story began to beg sympathy and derision in equal doses. (The same might be said of Lightning over Water and The State of Things, his films about filmmakers.)

Alice (1974) does possess one great advantage over Wrong Move: its ability to replace the failed poetry of literature (Rudiger Vogler, out of words, frantically snaps Polaroids) and romance (Vogler’s sexual turndown by a onetime girlfriend, one in a long litany of bedsheet discontents) with the one poetry that is authentic in Wenders – that of the road. Alice is the first of the director’s road movies; the goalie and the wrong-mover may travel, but they haven’t learned to enjoy the trip. That’s the one thing the hero of Alice does manage to learn. Not that it’s easy: a few days’ traveling along the motel-and McDonald-strewn wastelands of the U.S. of A. produces one smashed TV set and a strung-out writer who hasn’t spoken for two days. But once back in Germany, with an unwanted precocious little girl and the photograph of an unknown destination (a picture of grandma’s house), and Vogler’s on his way to being as much of a road junkie as he’s discovered to be at the opening of Kings of the Road (1976).

For the road, in its hypnotic black-and-white sameness, its strange attenuated time-sense (regulated stops freeing up lazy floating intervals, so that even taking a crap opens duned vistas), is highly addictive. Enter Hans Zischler, having abandoned job, wife, home, car: he drives his VW right off the road into the drink, to the watching Vogler’s stupefied admiration. An unlikely partnership is forged. The two self-styled kings of the road proceed to play off each other in madly convoluted ways. Psychologist Zischler insists upon a return to primal scenes, but in matched ludicrous sunglasses and on a commandeered motorcycle with sidecar; Vogler doggedly goes his projected rounds only to erupt into primal cinema – surprising a reluctant Zischler into a faultlessly timed Chaplinesque pantomime behind a movie screen. Finally, in a deserted U.S. Army barracks on a nameless frontier, all bets are off. Linguist Zischler deciphers the overlapping GI graffiti on the wall to read “THINGS MUST CHANGE” – a farewell note to his erstwhile friend.

A weird, fluid sense of passivity suffuses Vogler and Zischler’s Mutt ‘n’ Jeff adventures in the Twilight Zone. Everything shifts and nothing changes. Picaresque vignettes they just pass through – a bereft man mechanically tossing stones down a shaft in an industrial wasteland; chattering, anonymous children sailing paper boats under a medieval bridge – seem more vivid and personal than anything that supposedly happens to them. So, too, the angel come to corporeality in Wings of Desire who, despite his yearned-for shot at “real” life, remains no more connected to “his” story than he was to the various human figures over which he hovered unseen.

Unable to entirely be there for themselves or others, Wenders’ characters never manage to do anything. They are Hamlets all; opportunities, kingdoms, Ophelias slip through their fingers almost unnoticed. They’re not really adapted to action, any more than Wenders’ compositions are adapted to narrative. Stuck on an apolitical fence, unwilling to name the social logic of revolt or acceptance that would link image to image, Wenders can find no narrative framework other than that of dissociation (Goalie, the first part of Paris, Texas), false starts (Wrong Move), or multiple unfinished stories (Kings, American Friend, State of Things, Wings of Desire).

There’s a curious tension in Wenders’ work, a sort of contradictory anarchic self-sufficiency not unrelated to the political contradiction of his allegiance to Ray and Fuller on the one hand, Ford and Ozu on the other. Wenders’ compositions neither exclude (Ray and Fuller in their truncated syntax accusing all the human possibilities left out, violently) nor include (Ford and Ozu seeking, through stasis and ancestral communion, to preserve a vanishing way of life). Voided-out and dispassionate, his images – in their charged emptiness, their various displacements of motive and motivity – are like doors thrown open on the antechambers and aftermaths of an unknown play: hitting the epiphanies and the time-outs, just missing the action that would make all clear. Thus the complementary pairings, the insistence on alternatives – as if two dead ends were better than one.

The only real communication in Wenders is that of ships that pass in the night. The goalie and his box-office girl, half out of frame in the stark insistence of chairs, tablecloth, bowl, coins, under the nearby-airport noise of planes landing and taking off, talk of places they have been or would like to be, or where others have been. The two kings of the road, denied a proper leave-taking, meet in a semi-miraculous pas de deux as Zischler’s train and Vogler’s van sway, dip, glide on the separate routes that approach and recede in elegiac recognition.

Even if, by sheer fluke and the help of an American friend or two, one of Wenders’ symbiotic pairings lands his heroes (Hopper and Ganz) in a grand guignol Mafia gangwar instead of limbo, they have no place to go. Instead, they relate to each other in a crazy nonfunctional dialectic that takes the place of action. Just as Hopper sucks Ganz into his shoot-’em-up saga, his no-man’s-land time and space (appearing from nowhere in an isolated room of some or another city, to disappear and reappear elsewhere), so will Hopper be drawn into Ganz’s familial drama, his interconnected time and space (the overpeopled rooms of Ganz’s apartment cozily spilling into one another, the routes from his apartment to his car to his shop on-line and well traveled). Then, as plots thicken, Ganz’s still-detailed itineraries become increasingly erratic, disoriented: he bumps into walls, sets off electric shocks, till finally a handheld camera, striding purposefully forward from Ganz’s POV, illogically discovers … a sleeping Ganz. Meanwhile, back at the ranch, Hopper’s apparitions take on a lodestar inevitability – poles more fixed, trajectories more predictable – until each man is trapped in an impasse of the other’s devising.

The American Friend (1977), in its complex crosscut intersection of half-told tales, walks an exhilarating tightrope between the marginal and the conventional, continuity and discontinuity, American and European film. Wenders’ subsequent move to Hollywood tipped a balance that existed more in time than in space. For the Hollywood that Wenders found was not the one he sought. Gone the postwar uncertainty of Nick Ray or Sam Fuller, gone even the freewheeling marginality of the Sixties road movies. Hammett (1980), Wenders’ first Hollywood film, is grounded in thin air.

The layered fiction at the center of Hammett – the story he’s writing forever dreamsliding into the one he’s living (through and beyond his looking-glass typewriter) – never drops anchor. Good cop-bad cop duos, Chinese beauties, rich fat men, shady gunsels, Fu Manchus, and the gorgeous redhead next door pass by in shadowplay against one lurid backdrop after another. Even Hammett‘s nostalgia trip down film noir lane gets lost in subtexts without a text, in a clutter of superannuated oddball characters in odd corners with no angles, following the winding logic of sexual desire through a bordello where nobody’s buying.

In a fevered, unconscious way, Hammett looks like an ironically inverted mirror of that emptiest of neo-Hollywood forms, the clunky Chandler remakes. Farewell My Lovely may get glued down in the interior-decorator literalism of its propped-up reconstructions, but Hammett floats away on ballooned levels of supposition until all that’s left is the décor – surreal, to be sure, but still décor. And if a past-it Mitchum half-wakes to find himself condemned to relive lost Marlowe parts in a cardboard mockup of his heyday, Frederic Forrest, still wet behind the symmetrical patches of gray over his ears, looks as if he’s winging it until the script arrives.

It’s probably fruitless to speculate whether Wenders had the misfortune, the stupidity, or the unconscious desire to hit Hollywood at its most consciously fake mythoconservative. And certainly it’s unfair to blame the director entirely for the confused heroics of Hammet – his peculiar coda’ed editing style, his buildups to nothing and builddowns to events largely left on the Zoetrope floor. But Paris, Texas (1984) is very much a Wenders film. If Nick Ray occupied his films’ foreground, John Ford and The Searchers were always lurking in the woodpile. [1]

Strands left unfinished in Wenders’ German films, guilts still to be laid to rest, suddenly resolve themselves in the newfound innocence of overblown Hollywood simplicity. What was something to do becomes a heroic act, out-of-it wanderers turn into disinterested seekers-after-truth, while the limitations and ellipses of his characters become those of the film. The heretofore specifically placed male fear of sexual and familial involvement, for example, is conveniently integrated, in Paris, Texas, into the blame-mommy mentality of such Ordinary People as Kramer vs. Kramer. In fact, Wenders goes it one further to forgive mommy for her prostitute-underglass sins in a burst of masculine largesse. (How the hell the hero’s “grateful” wife is supposed to support the kid altruistically thrust upon her is left floating on the sentimental backwash of a reconstituted, somewhat lopsided family that now owes all to daddy as he poetically fades into the sunset.) Even Ford in The Searchers didn’t expect buck-ravaged Natalie Wood to thank John Wayne for returning her to her family instead of killing her for her ethnic fall from grace.

In Wender’s German films, the transpositions were explicit: heroes that wander in space because they cannot place themselves in time, seduced by the Lorelei call of Hollywood because they have no story or, being German, no story that can be told and lived with. Their surroundings emerge with the hard-edged clarity of what’s missing, and the incongruity and even the beauty of what’s there. But when Wenders tries to regain what’s lost, to recapture the plenitude of an image that belongs to an alternative, continuous system of representation, he finds neo-Hollywood reproducing itself in an incestuous nightmare of remakes and sequels to the Reaganist myth of the eternal return.

The various cute-kid stages of Harry Dean Stanton’s resocialization in Paris, Texas are all the harder to take coming as they do after an extraordinary opening: Stanton’s walkabout in the lone vastness of desert and his subsequent uneasy reentry into American civilization – his zombie presence constantly threatening to shift the plasterboard parameters of this jerrybuilt world by the very blankness of its intensity.

Some of this same intensity marks Wenders’ own reentry-into-Germany film Wings of Desire (1988). In many ways Wings of Desire is archetypal Wenders – the familiar lament of the artist-observer with no story of his own, in the guise of a parable of disaffected angels whose depressing job is to “observe and record” earthling miseries. They eavesdrop and take notes (their main hangout is the public library), stooping occasionally to administer hit-or-miss solace until driven by impotent rage and pity to desire either life (Bruno Ganz falls in love with a girl on a flying trapeze and dreams of saving her from herself and for himself) or death (brother angel Otto Sander, failing to stop a jumper, commits symbolic suicide in an act of empty empathy) – anything but this black-and-white limbo of unfinished lives, this litany of wars and waste. And somehow, despite the transparency of the premise and the accompanying whine of self pity, Wings often succeeds in conveying the orchestrated confusion of a mind too full of images, a mind in love with images. Newsreels, WW2 footage, reminiscing old men, oddball angel-actors, dizzying leaps into the void, autobahn underpasses, multilevel concentration-camp sets, neon nimbi of library lamps, and stretches of ramp jostle each other into feverish disorder as two angels follow “The Course of Time” – Im Lauf der Zeit, the German title for Kings of the Road.

This rich tension in time and of time survives even the brightly colored awfulness of Wings’s happy-ever-after, Bruno-Ganz-in-the-real-worId-with-a-story-of-his-very-own ending – not to mention its unspeakable, if spoken, moral: find a love story that will erase history, and you’ll find a story you can “really” live with. Better to cast back (impossible not to cast back) to the primacy of the black-and-white images that preceded the hyperchromatic finale, with their resistance to linear cause-and-effect, their refusal to be named, claimed, or appropriated.

Wenders here opts to parade history in a willful attempt to get it over with and get on with life as others, less obsessed with memory, lead it. If he but knew, the reality he seeks is the image. If only he could find the real house that corresponds to the photo of grandmother’s house, even if it’s not his grandmother, and even if she’s moved. In Tokyo-Ga, Wenders’ camera dazedly wanders the streets of the ultramodern capital, seeking in vain traces of Ozu’s tranquil city – according to his plaintive commentary, a world and a story that never changed, untouched by the war and its guilts, from a child’s camera position and through a 50mm lens that never varied. Like Keechie and Bowie who lived by Nick Ray’s night, Wenders has “never been properly introduced to the world.” Only to the movies.

Endnotes:

[1] The Searchers surfaces more and more explicitly in Wenders’ post-German films: in passed-around book form in The State of Things; the referent, visually and narratively, of Paris, Texas; and in a faded John-Wayne-at-the-graveyard clip in the graveyard-strewn Tokyo-Ga.

Originally published in Film Comment, Vol. 16 No. 1 (Jan/Feb 1980), pp. 54-64, 80.

Republished with permission from the estate of Ronnie Scheib.