When the Hollywood silent movie actress Claire Adams married Australian grazier Donald “Scobie” Mackinnon in 1937, the Australian press embraced the event as a glamorous love story. [1] After the couple moved to his property, Mooramong, near Skipton in the Western District of Victoria, Claire Mackinnon became part of the emergent, modern Australia of the mid-twentieth century. Remodelled by the Mackinnons in a style influenced by Beverly Hills homes, Mooramong brought modernity and distinctive glamour to rural Victoria. The Mackinnons also documented their lifestyle in home movies that include some of the earliest Australian amateur colour films. This article explores the ways in which Mooramong, now owned by the National Trust of Australia (Victoria), provides insight into the significance of Claire Adams in Hollywood, Australian society in the mid-twentieth century and the historical value of home movies. Although the story of Claire Adams is linked to Australia’s history of being dazzled by imported American commodities, ironically a full understanding of her story derives much from the preservation of Mooramong rather than from the United States. Mooramong provides insight into the complexity of the relationship between Australia and Hollywood in the mid-twentieth century, forming a contrast with the then commonplace notion that imported American entities were incompatible with and a threat to local culture.

The significance of Mooramong is linked to home history: the collecting, describing and analysing of residences. As historian Thomas J. Schlereth notes, the home is “a site, a space, and a symbol of enormous importance” for understanding the past; it has been variously “an inspiration for the literary imagination, a subject of artistic creativity, a metaphor for social reform, and an icon of social and economic status”. [2] That the historical significance of a home extends beyond private life to be part of the public sphere, and can be linked to important social developments, is exemplified by Mooramong, which Claire Adams Mackinnon bequeathed to the National Trust upon her death in 1978. The surviving property includes the house, its furniture and other contents, gardens, farm buildings and farm equipment, Claire’s collection of Hollywood publicity stills and the Mackinnons’ home movies. As a “historic house museum”, Mooramong is the locus of a “material culture” [3] that is significant partly because its boundaries exceed those of any one cultural form, presenting a view of a whole way of life. Like other “major institutional formats” of home history, such as the period room in a museum, the historic house offers a more immersive sense of the past than can be acquired from a document, a painting or an empty building. While the aspects of Mooramong that are most relevant to this article are its relationship to Claire Adams’ film career and the home movies, other aspects of the property are inextricably linked to these. Famous chiefly for being the home of a former Hollywood actress, this property and its preservation are exceptional in light of the fact that many other silent Hollywood actors lived their later lives in obscurity or guarded privacy. A fuller understanding of the property’s significance can be gained from becoming acquainted with Claire Adams’ earlier life, her career and marriage to Scobie Mackinnon.

Claire Adams in Hollywood

The early life and career of Claire Adams reveal the origins not only of her acting career but also of her life in Australia. She was born Berylvere Nassau Adams in 1896 in Winnipeg, Canada, a rural region in which she developed a love of the outdoors that she described as “an essential part of me”, and which prefigures her life at Mooramong. [4] Indeed, in 1920 she expressed to Motion Picture Classic magazine her discomfort with crowded American cities and the sense of remoteness from nature in New York. [5] The daughter of an opera singer, Stanley Adams, and a pianist, Lillian, Claire had two sisters and a brother, of whom the latter, Gerald Drayson Adams, became a Hollywood screenwriter (Kissin’ Cousins, USA 1964). Claire was educated in Canada and England [6] before appearing in short films for the Edison Company as Clara Adams in 1912 and 1913, and in later short films as Peggy Adams. She moved to Los Angeles to act in Riders of the Dawn (USA 1920) for independent producer Benjamin B. Hampton, a widower eleven years her senior, whom she married in 1924; she appeared in twelve films for Hampton from 1920 to 1922. Part of the significance of Claire Adams’ film career is in the number of her films, which include twenty-four shorts from 1912 to 1918 and fifty-three features from 1917 to 1927. [7] She has the principal female role in approximately two-thirds of her feature films; [8] those in which she is unequivocally the protagonist include two films for Hampton, The Dwelling Place of Light (USA 1920) and The Money Changers (USA 1920), and a Goldwyn production, The Great Lover (USA 1920). Her most prominent film is King Vidor’s The Big Parade (USA 1925), one of the highest-grossing silent features, [9] in which Adams plays the woman that Jim Apperson (John Gilbert) leaves behind when he goes to war. That Adams was a well-known actress is evident in letters published in the fan magazine Photoplay and entries about her in Who’s Who on the Screen (1920) and The Blue Book of the Screen (1924). [10] Closer examination of her career provides further insight into her distinctive relationship to the emergent Hollywood studio system.

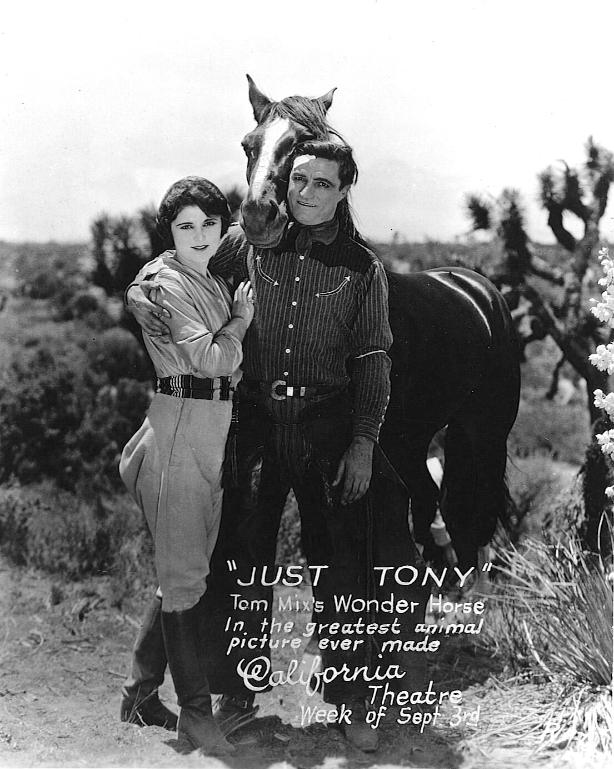

Claire Adams’ career is of significance for spanning a period of major changes in the American film industry, including the transition from short films to feature-length productions, the industry’s relocation from the East coast to Los Angeles, the establishment of the star system and the formation of vertically-integrated major studios. As Adams worked for both major and minor companies, her career provides an overview of a range of American film-making that is often not evident in histories that centre on major studios and major stars. Although her fame did not rival that of Mary Pickford, Rudolph Valentino, John Gilbert or Gloria Swanson, who were her contemporaries, the fact that she was employed almost continuously during her career is a considerable achievement in light of the “perennially overcrowded” aspect of the acting profession, which attracted “thousands of would-be motion picture performers […] to Hollywood in the 1910s and 1920s”. [11] A glimpse of the early film industry before its dominance by a small number of major studios can be obtained from Claire Adams’ work in the late 1910s for the Florida-based Klever Pictures and Pennsylvania-based Betzwood Film Company, of which the latter was described as the “largest, most advanced film studio” before the industry moved west. [12] That she was adaptable and eminently employable is suggested by the range of companies for which she made films in the 1920s, including five of the major studios (Fox Film Corporation; Universal Pictures; Warner Bros; Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, later Paramount Pictures; and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer) and smaller companies such as Tiffany Productions, Choice Productions, Chadwick Pictures Corporation and Zane Grey Pictures. She worked with such prominent stars as Lon Chaney (in The Penalty, USA 1920), Tom Mix (Just Tony, USA 1922; Do and Dare, USA 1922; Stepping Fast, USA 1923; Oh, You Tony!, USA 1924), Clara Bow (Helen’s Babies, USA 1924) and Adolphe Menjou and ZaSu Pitts (The Fast Set, USA 1924). While her films serve as an index of major changes in the film industry, Claire Adams’ career can also be linked to female types that appeared in Hollywood publicity during the emergence of the star system.

Adams’ public persona can be understood in relation to the idea of the New Woman. A social type that was identified in the 1890s with middle-class women who “engaged in educational, political, and occupational pursuits outside the home”, [13] the New Woman had by the 1920s become associated less strongly with feminism and social reformism than with individual fulfilment and, in the media, “consumerism and sexual expressiveness”. [14] Stephen Sharot writes that the “New Woman type that most closely signaled [sic] the relationship between consumerism and women’s emancipation […] was the flapper”, whose “short hair, use of cosmetics, smoking, short skirts, and flamboyant dancing […] was seen to personify a lifestyle condemned by conservatives as undermining morality and religion”. [15] Publicity for Claire Adams both echoes and distinguishes her from such contemporary Hollywood stars as Mary Pickford and Clara Bow. In publicity photos for one of her early films, Salt of the Earth (USA 1917), for instance, Adams displays a long, curly hairstyle and girlish appearance that can be likened to the public persona of Mary Pickford, who was strongly associated with “little-girl roles”. [16] Whereas Pickford was unsuccessful in shedding her little-girl persona in later years by portraying a flapper, however, by 1920 Claire Adams had adopted a more modern persona by wearing her hair up or in a bob style, of which the latter would become her trademark for the rest of her life. Indeed, Adams’ public persona can be seen to form a transition between the old-fashioned, somewhat Victorian persona of Mary Pickford and the flappers portrayed in films by Colleen Moore and Clara Bow. In contrast to Moore’s boyish flapper and Clara Bow’s more overtly sexual version of the flapper type, [17] Adams embodied a demurely feminine version of the New Woman. This is evident in Helen’s Babies, for example, in which her supporting role as the maternal character of Helen contrasts with Clara Bow’s portrayal of a neighbour who seduces Helen’s brother. While Claire Adams exhibited visual similarities to the flapper type, her public persona was associated less with sexual daring, smoking, dancing or parties than with demure roles or the outdoors.

Admired for her beauty, Claire Adams usually plays sympathetic, often refined, women, never vamps, predators or villains. [18] The construction of her public persona as alluring and warm without flamboyance is evident in a description in Motion Picture Classic magazine:

She is patricianly beautiful, Claire Adams, in a dark, intense way, patently a woman of the world, and possessed of all the easy charm that worldliness implies. Her voice, influenced by her life in Canada and London, is modulated and quiet. […] And this English deliberation has crept into her being, until it is an integral part of her life. [19]

Claire Adams is positioned in Hollywood as a more conventional female object of romantic desire than the unorthodox and overtly sexual New Women exemplified by Colleen Moore and Clara Bow. In her films, Adams is often cast in roles where she waits for a man and is sometimes rescued by a man. Men in several of her films compete for her love. Her role in the surviving Hampton film, Heart’s Haven, exemplifies the casting of her in roles typical of silent domestic melodramas, which place emphasis on female “martyrdom”, “anxiety” and “frustration”. [20] In this film, Adams’ character becomes paralysed in a fall and undergoes a miraculous recovery before forming a romantic union with the male protagonist, whose obnoxious wife has recently decided to divorce him before dying suddenly in a car accident with her lover. The film’s use of a somewhat implausible plot to explore themes of loveless marriage and romance is characteristic of silent film melodrama. Through these themes, Heart’s Haven attempts to reconcile a nineteenth-century view of love as an economic transaction with a more modern equation of love “with personal happiness and the affirmation of the self”. [21] Thus, Claire Adams’ persona has affinities with the New Woman through being linked to modern ideas about love, but is largely distinct from the flapper’s more controversial trait of sexual daring. Indeed, Adams’ most daring work on screen is associated not with melodrama but with the less prestigious genre of the silent Western.

Claire Adams’ equestrian skills form the basis of arguably her greatest achievements on screen. Earning a reputation as “one of the best horsewomen in the movies”, [22] she appeared in four films with Tom Mix, one of the most popular stars of silent Westerns. That her work is not more well-known may be attributed to the low status in this period of the silent Western, which since 1915 had attracted mainly younger viewers. [23] Nevertheless, Mix’s films were enormously popular. Their sprightly pacing and emphasis on entertaining stunts influenced the low-budget B-Western films of the 1930s. [24] Claire Adams’ equestrian skills are evident in the surviving film Just Tony, for example, in which she plays the only female character, Marianne Jordan. In this film, Adams rescues the hero, Jim Perris, played by Tom Mix, from being held captive. She also joins him in a horseback chase scene, in which Marianne rides ahead of Perris until both characters lose their rides and are rescued by Tony, his horse. Adams mounts the galloping stallion to join Perris, whereupon the trio speeds to safety. Thus, instead of waiting for a man, in Just Tony Claire Adams initiates events and performs stunts. Moreover, the fact that she appeared in three subsequent films with Tom Mix positions this series as an important component of her career. Her equestrian skills are further evident in another film, Where the North Begins, in a scene in which she is abducted on horseback. That she performed similar stunts in other films, which do not survive, is suggested in a review of When Romance Rides, in which Claire Adams is praised for her ability to “turn jockey and win a horse race at a moment’s notice”. [25]

The frequent prominence of animals in Adams’ films prefigures her life at Mooramong and echoes her rural upbringing in Canada. In light of her later contributions to animal welfare charities in Australia, the possibility that she chose to act with animals when the opportunity arose is supported by sympathetic depictions of animals in several of her films. Indeed, in Tom Mix’s films the character of Tony, played by Tony the Horse, has as much agency as the human characters. Also known as Tony the Wonder Horse, Tony belonged to Tom Mix and appeared in more than thirty films during the 1920s and 1930s. Animals are also central in several of Claire Adams’ other films. For instance, she appeared in two adaptations of Anna Sewell’s novel, Black Beauty, Your Obedient Servant (USA 1917) and Black Beauty (USA 1921). Narrated by the horse, the goal of Sewell’s novel to cultivate “empathy for those who cannot speak for themselves” [26] encapsulates a theme that has a recurrent significance in Adams’ films. In Where the North Begins, for example, a climactic scene centres on the reluctance of the canine character of Rin Tin Tin to trust his closest human friend after the man wrongly blames him for an infant’s disappearance. Similarly, in Just Tony the relationship between Tony and Jim Perris is positioned as an exception to the wild stallion’s usual distrust of humans. Dogs and horses are also central to When Romance Rides and feature in Heart’s Haven and The Man of the Forest (USA 1921). [27] Given the importance of animals’ rights in her films and in her life at Mooramong, Claire Adams’ oft-cited statement that Rin Tin Tin was “her favourite leading man” [28] is not as flippant as it might initially seem.

The circumstances surrounding Adams’ retirement from the screen are linked to her marriage to Benjamin Hampton. However, the professional advantages of her relationship with him are unclear given his pivotal but unsuccessful significance in the industry. In 1916, Hampton had proposed a merger of the distribution companies Paramount Pictures and VLSE (Vitagraph, Lubin, Selig and Essanay) with production companies Famous Players and Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company. The move was foiled by Adolph Zukor, who proceeded to expand Paramount Pictures into production and exhibition, thereby forming a model for the vertical integration of the film industry. [29] Although Hampton had been an early advocate of integrating film production and distribution, he unsuccessfully opposed the addition of exhibition to this model. [30] He was also one of the first film-makers to adapt the novels of Zane Grey to the screen and Claire Adams appears in five of these films. However, Hampton’s films were unprofitable and Grey sued him. [31] By 1926 Hampton had retired; [32] his most enduring contribution to film is his book, A History of the Movies (1931). By contrast, the possibility that Adams’ career was still ascending when she retired is suggested by a reference to her in Photoplay in 1925 as “a star in the making”. [33] Her retirement preceded the impact of talking films, confounding the question of whether her career would have survived the concomitant industry upheaval that contributed to ending the careers of such prominent contemporaries as Mary Pickford and John Gilbert. The most plausible reason given for Adams’ retirement is that Hampton became ill and the couple moved to Glen Arden Farm in Pawling, New York. [34] The move prefigures Claire’s relocation to Mooramong, in that Hampton, like Scobie Mackinnon, was a gentleman farmer. [35] However, the idyllic setting contrasts with the discovery by Adams’ biographer, Heather Robinson, that Benjamin Hampton physically abused his wife. [36] After inheriting half his estate of almost US$200,000, Adams sailed in 1936 for Britain, hoping to “break into films”, and performed on radio as a singer, [37] trained by her father, who later moved to Mooramong. Although Claire Adams appeared in no Australian feature films, she brought to rural Victoria an international influence that contributed to the increasing cosmopolitanism of Australia after World War Two.

Claire Adams and Mooramong

A Hollywood actress who migrated to Australia was an anomaly in the 1930s. Historian Richard White estimates that less than 1% of Australians had travelled overseas, but that for “those who could afford it, the 1930s were great years for travel” because the “luxury passenger liners were in their heyday”. [38] For the less affluent majority, Hollywood movies were a source of fantasies about “where they would go if time and money were no object”. [39] Most Australians who travelled abroad went to Europe. [40] A view of the activities of some Australians is provided by journalist Dorothy “Andrea” Jenner, who knew Claire and had also appeared in silent Hollywood films. [41] Jenner became concerned upon hearing of Claire’s engagement because a French law enforcement official had warned her of “Australian con-men” who were “known to be operating in Europe” and were considered to be “the best in the world”. [42] Scobie Mackinnon had inherited his wealth, however, and, like Claire, moved in privileged circles and had an interest in horses. [43] Born Donald John Scobie Mackinnon in 1906, his father was Lauchlan Kenneth Scobie Mackinnon, a Victorian Racing Club (VRC) chairman after whom the L.K.S. Mackinnon Stakes is named. Scobie received Mooramong as a twenty-first birthday gift from his father. He met Claire Adams Hampton at a London party in 1937, they married three weeks later, and, after a year-long honeymoon, moved to Victoria in 1938. [44] Although Scobie was prominent in the racing community and his horse, Contador, won the VRC Grand National Hurdle in 1962, [45] much of the public attention to Mooramong centres on his wife. Her association with Hollywood became a source of fascination for a post-war Australia that was coming to see itself as part of the modern world. Although Melbourne was “the most self-consciously modern” Australian city, writes historian Graeme Davison, in the 1950s and 1960s it was still “sometimes pathetically unsure of who or what it was”. [46] Indeed, Claire Mackinnon commented that Australia “seemed dull after the sophistication of the States and Europe”, although she later reversed this opinion. [47] Mooramong came to manifest the arrival of the modern and the international in rural Victoria.

Claire and Scobie’s transformation of Mooramong occurred during a period in which American influence in Australia was increasing. In the 1930s, the area of Australian life in which the presence of the United States was most strongly felt was the cinema. Australian feature film productions would become more infrequent in the 1940s and 1950s, presenting little competition to Hollywood on local screens. In the late 1930s and the 1940s, 75% of films in Australian cinemas were from Hollywood. [48] It was also in the 1940s that the United States sought to expand international markets for a wide range of American products by promoting a “liberal international economic order” that would replace existing “economic arrangements centred on colonial systems or socialist economies”, including Australia’s relationship with Britain. [49] Through exporting domestic and other goods that included cars, televisions and domestic appliances, as well as suburban lifestyles and advertising, the United States, “[m]ore than any other society, […] realised and encouraged that which was modern in the postwar world”. [50] Among the repercussions of such developments in Australia was increased debate about “Americanisation”, a term often used pejoratively to depict Australia as adopting “social practices and cultural values” associated with commodities from the United States, which were purported to be “not meaningful within the Australian context” but were seen as a threat to the nationalistic notion of “a uniquely Australian cultural and political identity and consensus”. [51] The relationship between Hollywood and Mooramong, however, defies a simple polarisation of American and Australian culture. Indeed, the significance of this property can be understood more fully in light of the more recent view, shared by various commentators, that “so-called Americanisation” is inseparable from the global process of “modernisation or consumer capitalism”, which is not simply a product of the United States. [52]

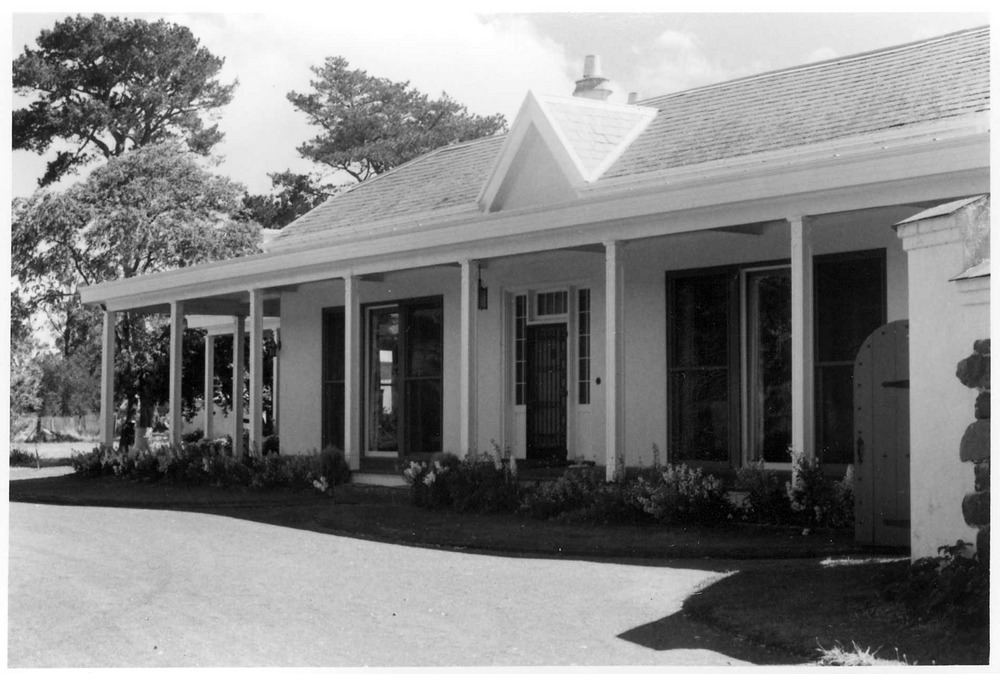

The Mooramong homestead was remodelled by the Mackinnons in a modish style that reflects the influence of American architecture. As originally designed for Alexander Anderson Jnr. in the 1870s by architects Davidson & Henderson, the homestead was a single-story Victorian house with “Gothic motifs”. [53] The renovations that Claire initiated in 1938 were designed by Melbourne architect Marcus Martin and included the removal of nineteenth-century interior details and Gothic exterior details; other changes included replacing windows, remodelling doors, applying white stucco rendering to the exterior walls and adding a swimming pool, pavilion, pergola and rendered wall. [54] This modernisation is consistent with other work by Marcus Martin, who was a fashionable “key figure” in Melbourne architecture. [55] Martin had designed homes in Toorak and South Yarra for such clients as William Murray-Smith, Tristan Beusst and L.K.S. Mackinnon, whose 1935 house at 220 Domain Road [56] became Scobie and Claire’s city residence. Martin’s work reflected the influence of the Mediterranean revival style, which had proliferated in California and was inspired loosely by Spanish mission architecture. [57] The popularity in Australia of Spanish and other Mediterranean architectural elements is exemplified at Mooramong by the unadorned, white stucco walls and arched doorways. [58] At Mooramong, Martin also incorporated modern elements such as fireplaces with strong horizontal lines, updated light fittings, built-in kitchen and bathroom fittings and benches made of Formica, which was not widely available in Australia. [59] In homemaker articles in The Australian Women’s Weekly, for example, “tempered pressed wood” is promoted as the ideal material for kitchens in the 1930s; Formica is not featured until the 1950s. [60] That the Great Depression had halted the Australian “suburban boom and […] much building activity for the rest of the decade” [61] also made Mooramong unusual. At the same time, the fact that the homestead’s basic structure remained unchanged is consistent with the idea that the modern involves a convergence of “historical moments”, forming “an amalgam of the past, the contemporary and the future”. [62]

Mooramong can be likened to the famed homes of early Hollywood stars. In particular, the Mackinnons’ renovations echo the Mediterranean revival styles of the homes of Buster Keaton, Charles Chaplin, Gloria Swanson, Rudolph Valentino and Tom Mix. [63] At Mooramong, the influence of contemporary American popular culture is particularly evident in the games room, where the Mackinnons added a cocktail bar featuring “a green leather dado with chrome cover strips, green carpet, curved bench and recessed fireplace”. [64] An extravagance consistent with Hollywood became apparent with the addition of large mirrors and the renovation of the bathrooms, including a mirrored vanity with elaborate lighting that brings to mind the dressing rooms of film stars. Most strikingly redolent of stars’ homes is the swimming pool, which received publicity for being “the first private heated pool with change room in Victoria” [65] and is a setting for many of the Mackinnons’ home movies. Similarities between the homestead and contemporaneous Californian architecture can be seen in reels of the home movies that are filmed at Claire’s house in Beverly Hills. Like Mooramong, the Beverly Hills house is in Spanish Revival style and features white stucco rendering, arched doorways and a statue of a reclining nude woman, of which the latter is now situated at Mooramong. [66] Whereas many Los Angeles homes of Hollywood silent actors have been either renovated beyond recognition or demolished, however, the architecture and interiors at Mooramong remain almost unchanged since the 1930s, even surviving a bushfire in 1944. [67] Far from Beverly Hills, at Mooramong the juxtaposing of Hollywood styles with a rural Australian location seems to confirm that Hollywood “isn’t really” Los Angeles but “a state of mind” without boundaries. [68] The significance of Mooramong manifests the idea that “cinema culture knows no borders: each cinema artefact, of whatever origin, leaves a memory trace with its audiences.” [69]

The preservation of Mooramong as a museum in the style of the 1930s echoes the Mackinnons’ conservation of the natural environment. Predeceased by Scobie in 1974, Claire’s bequest to the National Trust specifies that Mooramong, its gardens and surrounding lands be maintained “as a wildlife sanctuary and flora and fauna park for the people”. [70] Central to her ethos of conservation was Claire’s love of animals, [71] which is evidenced in her charitable contributions to the Animal Welfare League Lort Smith Animal Hospital and the Cat Protection Society, as well as her adoption of homeless dogs. [72] Like Claire’s earlier life in Pawling, [73] Mooramong belongs to a tradition of wealthy patrons of small towns. Formerly “synonymous with the Victorian squattocracy”, the region retained the idea of a Western District Establishment even though many of the original families had left. [74] Local beneficiaries of the Scobie and Claire Mackinnon Trust include the Skipton & District Memorial Hospital and Skipton Primary School. [75] Claire’s father, known as “Pop” Adams, founded Carols by Candlelight and a Music and Drama Society in Skipton and raised money for the Australian Comforts Fund by giving wartime performances with Claire. [76] Young people from the Skipton area were invited to use the Mooramong pool, where the Mackinnons filmed a children’s Christmas party in 1939. [77] Although they brought American influence to the Western District, the Mackinnons’ contributions to the environment and the local community reflect their lasting investment in Australia.

Mooramong and Claire Mackinnon became objects of fascination for an Australia that was embracing consumer culture and styles from abroad. After World War Two, in particular, the lives of Australians were transformed by the availability of domestic appliances, cars and other commodities. [78] The transformation of Mooramong into a “district showplace” had foreshadowed the modernisation of the lives of ordinary Australians, and after the war it continued to embody the extravagant lifestyles of rich and famous people. [79] For instance, the aspirations of the majority of Australians as consumers in the 1950s centred on owning such items as a “Holden, nylons, and Heinz baby foods”, whereas the Mackinnons had owned a Bentley and a Rolls Royce throughout the wartime rationing of petrol and before many Australians could afford a car. [80] While contemporary American popular culture became very influential in Australia after the war, Claire Mackinnon represented an earlier phase of Hollywood in which the idea of the movie star had its origins. A fascination with Hollywood glamour is evident in the memoirs of ABC radio publicist Bonnie McCallum, who writes that Claire exuded “star quality from top to toe, from her big dark eyes shaded by a softly swathed cloche […] to her high-heeled ‘showgirl’ ankles” and in her “shopping sprees in the best film star tradition”. [81] That much of the story of Claire Adams Mackinnon has been told in Australian publications [82] can be attributed partly to the availability of a wealth of information at Mooramong but also to a recognition that this story represents an intriguing, local alternative to the trajectories of other silent Hollywood actors.

Claire Mackinnon’s glamour is central to her attraction for Australians. Although “glamour is notoriously difficult to define”, writes Stephen Gundle, “all agree […] that it is a quality attaching to persons that is instantly perceptible to those who encounter it.” [83] Rarely disputed is that the “most complete embodiment of glamour […] is the Hollywood film star.” [84] Gundle identifies the birth of the modern age with the inception of glamour, which offered “an imaginative synthesis of wealth, beauty, and notoriety that was enviable and imitable rather than a hereditary prerogative.” [85] Indeed, Australians had exhibited a strong attraction to glamour before Claire Mackinnon arrived. Australian women, in particular, had been influenced by styles of personal adornment in theatre and the movies since the first years of the century. [86] Grooming habits and favoured products of Hollywood stars were featured in Australian newspapers of the 1920s and 1930s. [87] However, some commentators believed that in Australia the importance of “local individuality” continued to vie with “excessive deference” to imported trends in fashion. [88] Indeed, for Australians in the early and middle decades of the twentieth century, glamour was commonly associated with that which originated from abroad. In Claire Mackinnon, the premise of the Hollywood star system that “anyone, potentially, could be a star” [89] seemed to be encapsulated by the fact that she was a Hollywood actress who lived in Australia. Just as glamour encompassed a circulation of information, products and experiences that seemed to extend this quality to all, the Australian public’s interest in Hollywood fuelled enthusiasm for glamour locally.

Claire Mackinnon can be situated within a history of European fashion in Australia after the Second World War. The Mackinnons became part of high society in Melbourne, where their presence at the races, the theatre, charity balls and Government House functions was reported in newspapers. [90] Despite making local friends and acquaintances, however, Claire’s glamour seemed exotic in the conservative context of post-war Australia, where women had long been interested in fashion but Paris designs were traditionally available only to the wealthy. [91] Anecdotes about Claire Mackinnon’s propensity to stop to rescue injured dogs while “being driven to a function in full evening dress” [92] attest to a local impression that her glamour was unusual in this environment. Indeed, her activities contribute to a fuller understanding of the relationship between the local and the international in post-war Australian fashion. As fashion historian Margaret Maynard notes, Australians in the late 1940s and the 1950s responded with “anxiety” to imported styles, such as Christian Dior’s “New Look”, and exhibited ambivalence towards European fashion. [93] Whereas histories of post-war Australian fashion are dominated by accounts of the influence of Georges and Le Louvre, stores situated in Melbourne’s Collins Street, less detailed information is available about who their customers were. Claire Mackinnon, for example, acquired a reputation for parking outside Georges in her “lavish lime and grey Rolls Royce” and making extravagant purchases within. [94] She also contributed to broadening conservative tastes by organising fashion parades to raise funds for the Lort Smith Animal Hospital. A 1952 function at the Menzies Hotel, for instance, featured clothing from Le Louvre and hats by Henriette Lamotte. While the event attracted considerable interest, The Argus newspaper was prompted to reassure its readers: “don’t be alarmed, for as Le Louvre’s Lil Wightman says: ‘Chic women are chic the world over, and Melbourne women […] will adore and adapt the new line in spring fashions’”. [95] Claire Mackinnon helped to introduce foreign styles and the possibility of everyday glamour to mid-twentieth century Australians.

The Mooramong home movies

Among the most vivid documents of the Mackinnons’ lifestyle are Claire and Scobie’s home movies. As well as serving as a historical record of Mooramong and the Mackinnons’ social life, the films have significance in relation to the history of amateur film and Australian society. Like the historic house museum, the home movie is a form in which family history intersects with public institutions, social iconographies and consumer technologies. [96] Although home movies have traditionally been judged by historians and other scholars to be “lowbrow” and not worthy of “serious” consideration, amateur films are increasingly being recognised to have significance and a range of potential uses, including as historical and cultural records. [97] Home movies on film are precursors to today’s amateur digital videos, of which abundant examples are available at YouTube, and manifest the potential for “anyone” to “become a producer” in order to utilise the “egalitarian” potential of audiovisual media, a goal famously outlined by Hans Magnus Enzensberger in 1970. [98] Patricia R. Zimmermann argues that home movies challenge existing ways of thinking about cinema by forming “a visual practice emerging out of dispersed, localized, and often minoritized [sic] cultures” and by offering alternatives to official history through being linked to “the more variegated and multiple practices of popular memory”. [99] In contrast to official histories of film, home movies offer “a different formation of film history from below”. [100] Situating the Mackinnons’ films in a tradition of home movies enables a fuller understanding of how these films bring together the private and public, the individual and the social, the expository and the performative.

In relation to the history of Australian home movies, the Mackinnons’ films are significant for including relatively early amateur colour films. Enabled by the invention of 16mm film in 1923, home movies were initially made only by the wealthy because cameras were expensive. [101] Early Australian colour home movies that are housed in the National Film and Sound Archive include tinted films made about the Albion family in the 1920s; Frederick Simpson Dyer’s films of family events in 1941; and Ewan Murray-Will’s films of Australia’s 150th anniversary (1938) and the Ballet Russes (1939). The Mackinnons’ home movies consist of more than 170 reels of silent 16mm film, almost all of which are colour, produced by the couple in the years from 1937 to the early 1970s. Most of the Mackinnons’ films are undated and only two have been edited into narrative form, with the result that the temporal and chronological contexts of most reels and the exact geographic settings of some reels are unknown. Their films encompass both private and public subject matter, including historic colour footage of MacArthur Park and the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles. However, the majority of the content of the Mackinnons’ home movies is Australian.

The Mackinnons’ films can be situated within a subcategory of home movies that consists of works by people with professional film-making experience, of which the domestic films of Charles Chaplin and videos of Stanley Kubrick are prominent examples. In Australia, amateur films made by people with links to the professional performing arts include Winnie Colleano’s 1939 films of her husband, Australian tightrope walker Con Colleano, alongside which the Mackinnons’ home movies can be situated. Home movies involving professional film-makers or performers are of interest not only because of their famous participants but also because these films challenge us as to what an amateur film is. As Nico de Klerk writes of a series of Dutch films made in 1920 that include scenes of the private lives of American film stars, these early home movies are unusual for being made primarily by the wealthy and for their tendency to display “a professional mode of production” in the guise of amateur style. [102] Similarly, the Mackinnons’ home movies suggest an ambiguous relationship between amateur and professional production in shots in which Claire holds a still camera, and in close-ups that linger on her face in a manner reminiscent of her Hollywood films. The fact that the Mackinnons’ two edited shorts are designed as silent films, including title cards, may be read to suggest that Claire’s professional experience in the years before talking films shaped her cinematic language. Indeed, the power of the silent image is evident in one of the films, A Journey to the Wild Flowers of California, in strikingly reflexive shots of the travellers setting up a still camera in a vast field of flowers. At the same time, however, the Mackinnons’ films have affinities with the wider category of amateur home movies. De Klerk notes that home movies are typified by “cooperative” production and the use of a “home movie visual idiom”, which includes appearances by family members, “convivial, performative” humour, and images recorded as “personal memories” that have a universal capacity to communicate “ordinariness”. [103] In the Mackinnons’ films, cooperative production is suggested by the fact that both Claire and Scobie appear frequently on screen and seem to have shared the task of operating the camera; indeed, Scobie is credited as director and cinematographer on one of the edited shorts, The Birth of a Nation. Similarly, a privileging of personal memories in the films is suggested by the frequent presence of family members and a large array of dogs.

Film history and social history are intertwined in the Mackinnons’ films, which offer a more elaborate view of mid-twentieth century Australian society than is evident in many publicly available home movies. The Mackinnons’ films of their social life are perhaps the most complex component of the home movies because of the large array of people featured in them. These include political figures and members of the performing arts, as well as other striking personages and locations that simultaneously provoke the viewer’s curiosity and elude identification. Among the well-known figures who can be identified at Mooramong are Robert Menzies and his daughter, Heather, whose teenage appearance suggests that these images date from the 1940s, between his two terms as prime minister. Also identifiable in the films are Menzies’ close friends, the tennis champion Sir Norman Brookes and his wife, Dame Mabel Brookes, whom Claire knew through the Animal Welfare League. Other visitors to Mooramong include a youthful Malcolm Fraser, the Aspro heir Lindsay Nicholas and a range of artistic and cultural figures that includes performer Evie Hayes; conductor and composer Eugene Goossens; journalist and broadcaster Dorothy “Andrea” Jenner; soprano Erna Berger; Claire’s brother, screenwriter Gerald Drayson Adams, and her father, opera singer Stanley Adams. [104] The Mackinnons’ home movies offer a more informal view of these public figures than can be obtained from their professional appearances alone. In one of the films, the presence of Zane Grey with Claire and Scobie on a boat suggests that Claire maintained a friendship with the novelist after he took legal action against Benjamin Hampton. As well as offering an intimate and informal view of a privileged Western District lifestyle, these home movies reveal that Mooramong came to serve as an artistic hub where the Mackinnons played hosts to visiting musicians and other entertainers from abroad.

These films offer an alternative to the now commonplace view that Australia in the 1950s was “dull”, “conformist” and “boring”. [105] The conservatism of the period is exemplified by the politics of Robert Menzies, prime minister from 1939 to 1941 and 1949 to 1966, who opposed Communism, denied the existence of class difference in Australia and promoted family values. [106] At Mooramong, however, conservative family values are often absent or are manifested in outlandish ways. Childless, the Mackinnons provided a home for more dogs than children and Claire took equal interest in the welfare of farm animals. In a photograph taken at Mooramong, she proudly supervises five lambs who are feeding from a rack holding bottles of milk. The Mackinnons also developed a reputation for holding sophisticated parties. Lina Caneva’s 2009 documentary, Mooramong: Private Hollywood, credits Claire with introducing the Western District to cocktails, a “new way of entertaining” that made use of the bar at the homestead. In addition, amateur theatrics occurred frequently at the property. An example is the short film, The Birth of a Nation. Here, Claire’s parents and sister are cast as anxious family members awaiting a birth, which Claire ultimately reveals to be, bizarrely, a dog’s litter of five rabbits. The title’s reference to D. W. Griffith’s eponymous 1915 film is irreverent, proudly eschewing the latter’s self-importance, and the film further flaunts its cinematic literacy in the final title: ”What would Lubitsch do?”

The Mackinnons’ home movies are unusual for providing the public with an informal view of the later private life of a silent Hollywood actress. They chronicle a flamboyant lifestyle that is exemplified by an array of musical performances, often in the grounds of Mooramong and occasionally at other properties. Examples are a vocal performance by the Hawaiian tenor Tandy Mackenzie and a Highland dance by Scobie. Many times in the films, Claire dances in the grounds of Mooramong while wearing an array of glamorous bathing suits and glittering costumes. Various friends and family members join her in these uninhibited theatrics, silent musical numbers that recall publicity images of the 1920s in which Claire Adams is positioned as a bathing beauty. In a 1922 issue of Photoplay, for example, she is photographed in Harold Lloyd’s “celebrated” swimming pool with the comedian and five other actresses. [107] The bathing beauty type had featured in Hollywood films and publicity since 1915, most notably in the work of Mack Sennett, and by the 1920s was linked to the cultural significance of the modern, emancipated young woman. [108] In the home movies, Claire Mackinnon can be seen to transpose the bathing beauty from silent cinema into mid-century and post-war Australia. While these performances recall the New Woman type of the 1920s, however, in the Mackinnons’ films this type is presented in a more informal and spontaneous way, as well as in Kodachrome. Defying the conservative dignity of many of her Australian female contemporaries, at an age that can be estimated to be at least fifty in some of the dance numbers, Claire Mackinnon is both an idiosyncratic anomaly in regional, post-war Australia and an influence on Australia’s emergence as a cosmopolitan, international society.

The significance of Mooramong is linked to the Hollywood career of Claire Adams, whose story can be understood more fully because of the preservation of this Australian rural property. As a historic house museum, Mooramong is significant for being the home of a former silent film actress, a Hollywood-style residence that is linked to the emergence of modern Australia, and a property that has served as a regional hub for visiting international performers and other public figures. At Mooramong, the culture of silent Hollywood extends beyond Los Angeles to suggest that a modern, international lifestyle has no geographic boundaries. While associated with the elite classes of the Victorian squattocracy and twentieth-century high society, the Mackinnons’ property is of wider significance because of the property’s relationship to film history, social history, modernity and popular film culture.

Acknowledgments

The staff and resources of the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) have been invaluable to the development of this article. The collections of the State Library of Victoria, the University of Melbourne and the Media History Digital Library were also indispensable.

Endnotes

[1] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 April 1937, 10; Kalgoorlie Miner, 1 April 1937, 5; West Australian, 2 April 1937: 7.

[2] Thomas J. Schlereth, “Introduction: American Homes and American Scholars”, American Home Life, 1880-1930, ed. Jessica H. Foy and Thomas J. Schlereth (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992), 1.

[3] Schlereth, 3.

[4] Motion Picture Classic, December 1920, 76–77.

[5] Motion Picture Classic, December 1920, 76.

[6] Birth date obtained from Manitoba Vital Statistics Agency (http://vitalstats.gov.mb.ca/). Differing birth years are given in other sources, including both of her marriage certificates and a memorial plaque at Mooramong. Charles Donald Fox and Milton L. Silver, eds, Who’s Who on the Screen (New York: Ross, 1920), 239; Ruth Wing, ed., The Blue Book of the Screen (Hollywood, CA: Pacific Gravure, 1924), 1.

[7] Adams is credited in two further feature films, Missing Daughters (USA 1933) and What a Mother-in-Law! (USA 1934), but both are re-released versions of earlier films (Missing Daughters [USA 1924] and The Lunatic [USA 1927] respectively). She also appears in an episode of the TV series Empire (a.k.a Big G) (USA) in 1963.

[8] Her surviving films are The Office Boy’s Birthday (USA 1913), A Misfit Earl (USA 1919), The Penalty (USA 1920), Just Tony (USA 1922), Heart’s Haven (USA 1922), Where the North Begins (USA 1923), Daddies (USA 1924), Helen’s Babies (USA 1924) and The Big Parade (USA 1925).

[9] Richard Koszarski, An Evening’s Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture 1915–1928 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1990), 33.

[10] Photoplay XXII.5, October 1922, 121; Photoplay XXIII.1, December 1922, 123; Photoplay XXVI.4, September 1924, 93; Photoplay XXVIII.4, September 1925, 90; Photoplay XXIX.6, May 1926, 106; Fox and Silver, 239; Wing, 1.

[11] Sean P. Holmes, “And the Villain Still Pursued Her: The Actors’ Equity Association in Hollywood, 1919–1929”, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 25.1 (2005), 31.

[12] Blair Miller, Almost Hollywood: The Forgotten Story of Jacksonville, Florida (Lanham, MD: Hamilton, 2013), 95; Betzwood Film Archive, accessed 16 August 2013, http://mc3betzwood.wordpress.com/.

[13] Stephen Sharot, “The ‘New Woman’, Star Personas, and Cross-class Romance Films in 1920s America”, Journal of Gender Studies 19.1 (2010), 74.

[14] Sharot, 74.

[15] Sharot, 74.

[16] Sharot, 77.

[17] Sharot, 79–82.

[18] In the infrequent instances where Adams plays a character of ill repute, such as a thief in The Brass Bowl (USA 1924), the character is usually redeemed.

[19] Motion Picture Classic, December 1920, 76.

[20] Ben Singer, “Female Power in the Serial-Queen Melodrama: The Etiology of an Anomaly”, Silent Film, ed. Richard Abel (London: Athlone, 1996), 169.

[21] Sharot, 76.

[22] Pawling-Patterson News XXXI.22, 27 May 1932, 1.

[23] Koszarski, 288.

[24] Benjamin B. Hampton, History of the American Film Industry from its beginnings to 1931 (New York: Dover, 1970), 124; Koszarski, 290.

[25] Photoplay XXII.2, July 1922, 54.

[26] Kristen Guest, “Introduction”, Black Beauty, by Anna Sewell (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2011), vii.

[27] American Film Institute Catalog (Ann Arbor, MI: Chadwyck-Healey, 2002).

[28] Bonnie McCallum, Tales Untold: Memoirs of an ABC Publicity Officer (Melbourne: Hawthorn Press, 1978), 32.

[29] Hampton, 150–162.

[30] Hampton, 151–3, 265–272.

[31] Thomas H. Pauly, Zane Grey: His Life, His Adventures, His Women (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 147, 215.

[32] The Yonkers Statesman (NY), 6 April 1926, 5.

[33] Photoplay XXVII.5, April 1925, 23.

[34] Courier-Mail (Brisbane), 1 April 1937, 16; Sydney Morning Herald, 1 April 1937, 10; Pawling-Patterson News-Chronicle (NY), 22 March 1979, 4–5.

[35] Brewster Standard (NY), LXIII.41, 5 February 1932, 1. Glen Arden Farm later became famous for being the final home of broadcaster Edward R. Murrow.

[36] Heather Robinson, telephone conversation with author, 30 October 2013.

[37] Pawling Chronicle (NY), 29 October 1932, 1; Dorothy Gordon Jenner and Trish Sheppard, Darlings, I’ve Had a Ball! (Sydney: Ure Smith, 1975), 230; Western Morning News (Devon), 16 September 1936, 7; New York Times, 19 September 1936; Evening Telegraph (Angus), 16 March 1937, 9; Nottingham Evening Post, 17 March 1937, 6.

[38] Richard White, “Overseas”, in Australians 1938, ed. Bill Gammage and Peter Spearritt (Broadway, NSW: Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, 1987), 438.

[39] White, 439.

[40] White, 439–441.

[41] Bridget Griffen-Foley, “Jenner, Dorothy Hetty Fosbury (Andrea) (1891–1985)”, in Australian Dictionary of Biography, accessed 23 June 2014, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/jenner-dorothy-hetty-fosbury-andrea-12697/text22889.

[42] Jenner and Sheppard, 230;

[43] Motion Picture Classic, December 1920, 76.

[44] Virginia Maxwell, “Mackinnon, Donald John Scobie (1906–1974)”, in Australian Dictionary of Biography, accessed 20 September 2013, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mackinnon-donald-john-scobie-11422/text19553.

[45] Maxwell.

[46] Graeme Davison, “Images of Modern Melbourne, 1945–1970”, Journal of Australian Studies 22.57 (1998), 145, 150.

[47] Pawling-Patterson News-Chronicle, 22 March 1979, 4.

[48] Diane Collins, Hollywood Down Under (North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1987), 66.

[49] Philip Bell and Roger Bell, “Introduction: The Dilemmas of ‘Americanisation’”, in Americanization and Australia [sic], ed. Philip Bell and Roger Bell (Sydney: UNSW Press, 1998), 2–3.

[50] Bell and Bell, 4.

[51] Bell and Bell, 6.

[52] Bell and Bell, “Introduction”, 6; see also Richard Waterhouse, “Popular culture”, in Bell and Bell, Americanization and Australia, 46.

[53] John & Thurley O’Connor, architects, Mooramong, Buildings and Structures: Conservation Analysis Report for the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) (Melbourne: National Trust of Australia [Victoria], 1989), 11, 22–3; Allan Willingham, “Davidson & Henderson”, in The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, ed. Philip Goad and Julie Willis (Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 194–5.

[54] John & Thurley O’Connor, 15–16; Bryce Raworth, “Marcus Martin: A Survey of his Life and Work” (Thesis, University of Melbourne, 1986), 33.

[55] Bryce Raworth, “Martin, Marcus”, in Goad and Willis, 432.

[56] Raworth, “Marcus”, 9, 11, 20, 25.

[57] Barbara Rubin, “A Chronology of Architecture in Los Angeles”, Annals of the Association of American Geographers 67.4 (December 1977), 528–9.

[58] Rubin, 529; Bryce Raworth, “Mediterranean Influences”, in Goad and Willis, 449; Raworth, “Marcus”, 11–12.

[59] John & Thurley O’Connor, 31; Raworth, “Marcus”, 22.

[60] “Modern Home for a Bride”, Australian Women’s Weekly, 3 June 1939, 58S [sic]; “Kitchen with a Future”, Australian Women’s Weekly, 9 April 1952, Homemaker supplement, 32.

[61] Mark Rolfe, “Suburbia”, in Bell and Bell, Americanization, 67.

[62] Robert Dixon and Veronica Kelly, “Australian Vernacular Modernities: People, Sites and Practices”, in Impact of the Modern: Vernacular Modernities in Australia 1870s–1960s, ed. Robert Dixon and Veronica Kelly (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2008), xv.

[63] Marc Wanamaker, Early Beverly Hills (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2005).

[64] John & Thurley O’Connor, 31.

[65] Donna Hellier, “Social History Report on Mooramong, Skipton”, in John & Thurley O’Connor, 7; George Beiers, Houses of Australia (Sydney: Ure Smith, 1948), 68; Australian Women’s Weekly, 22 November 1941, 43.

[66] Pawling-Patterson News, XXXI.47, 18 November 1932, 1; Hellier, 6.

[67] Claire Mackinnon, Mooramong Fire 1944 (Warrnambool, Vic: Philprint, 1944).

[68] Richard Maltby, Hollywood Cinema (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995), 1–2.

[69] Nico de Klerk, “The Nederlands Archive/Museum Institute”, in Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories, ed. Karen L. Ishizuka and Patricia R. Zimmermann (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 142.

[70] Claire Adams Mackinnon, Will, 31 January 1975, 2.

[71] Hellier, 5.

[72] Felicity Jack, The Kindness of Strangers: A History of the Lort Smith Animal Hospital (North Melbourne: Spinifex, 2003), 91–2.

[73] Pawling-Patterson News-Chronicle, 22 March 1979, 4.

[74] Philip Ayres, Malcolm Fraser: A Biography (Richmond: William Heinemann Australia, 1987), 51–2.

[75] Donald John Scobie Mackinnon, Will, 21 June 1968, 3.

[76] Hellier, 10; McCallum, 30.

[77] Lina Caneva, Mooramong: Private Hollywood (Caneva Media Productions, 2009); Inventory of films at Mooramong, in John & Thurley O’Connor.

[78] Stella Lees and June Senyard, The 1950s: How Australia Became a Modern Society, and Everyone got a House and Car (Melbourne: Hyland House, 1987), 141.

[79] McCallum, 33.

[80] Lees and Senyard, 1, 10–11, 17–20, 54–5.

[81] McCallum, 30, 33.

[82] See, for example, Beverley Will, “Gallant and Romantic were the Days of Claire Adams, Star of Silent Movies”, Green Place, October 1978, 29–31; Virginia Maxwell, “Jazzing It Up: Claire Adams and Donald Mackinnon, Former Owners of National Trust Homestead Mooramong”, Trust News 18.4 (1989), 14–16, 18; Sandra Pullman, “Mooramong, is it Edna’s Garden, or Claire’s?”, Australian Garden History 16.5 (May–June 2005), 10–15.

[83] Stephen Gundle, Glamour: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 2–3.

[84] Gundle, 172.

[85] Gundle, 18.

[86] Amanda G. Taylor, ‘A Fashionable Production: Advertising and Consumer Culture on the Australian Stage’, Journal of Australian Studies, 23.63 (1999), 119–120.

[87] Brisbane Courier, 22 July 1925, 10; Queenslander, 5 January 1928, 46; Register (Adelaide), 21 September 1929, 14; Camperdown Chronicle, 4 January 1930, 4; Brisbane Courier, 10 January 1931, 21; Sydney Morning Herald, 13 November 1931, 4.

[88] Williamstown Chronicle, 10 August 1889, 2; Argus (Melbourne), 24 February 1926, 6; Margaret Maynard, Out of Line: Australian Women and Style (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2001), 16–18.

[89] Gundle, 172.

[90] Sydney Morning Herald, 8 November 1939, 5; Argus, 20 June 1946, 10; Australian Women’s Weekly, 2 November 1946, 17; Argus, 2 November 1948, 9; Argus, 16 May 1955, 11; Argus, 17 September 1955, 9.

[91] Bonnie English and Liliana Pomazan, Australian fashion Unstitched: The Last 60 Years (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 18.

[92] Jack, 92.

[93] Margaret Maynard, “’The Wishful Feeling about Curves’: Fashion, Femininity, and the ‘New Look’ in Australia”, Journal of Design History 8.1 (1995), 51–5.

[94] Courier (Ballarat), 15 July 2001, accessed 8 August 2013, http://www.thecourier.com.au/story/321404/an-insight-into-skiptons-hollywood-home/.

[95] Argus, 23 August 1952, 12; Argus, 8 July 1952, 7; Argus, 24 August 1954, 10.

[96] Patricia R. Zimmermann, Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), ix.

[97] Karen L. Ishizuka, “Foreword”, in Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories, ed. Karen L. Ishizuka and Patricia R. Zimmermann (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), xiii–xiv.

[98] Hans Magnus Enzensberger, “Constituents of a Theory of the Media”, in The New Media Reader, ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 265–6; see also Zimmermann, Reel, ix.

[99] Patricia R. Zimmermann, “Introduction: The Home Movie Movement: Excavations, Artifacts, Minings”, in Ishizuka and Zimmermann, 1.

[100] Zimmermann, “Introduction”, 2.

[101] Caneva; Elizabeth Taggart-Speers, “Curator’s Notes: Australia’s 150th Anniversary Celebrations, Sydney”, Australian Screen, accessed 16 July 2013, http://aso.gov.au/titles/home-movies/australias-150th-anniversary/notes/.

[102] De Klerk, 143–4.

[103] De Klerk, 144–6.

[104] McCallum, 31–33.

[105] Lees and Senyard, 1.

[106] Lees and Senyard, 35.

[107] Photoplay XXII.6 (November 1922), 70; publicity stills for Missing Daughters (1924), National Trust of Australia (Victoria).

[108] Angela J. Latham, “Packaging Woman: The Concurrent Rise of Beauty Pageants, Public Bathing, and Other Performances of Female ‘Nudity’”, Journal of Popular Culture 29.3 (Winter 1995), 151–2.