Ford At Fox

4.1 Introduction to Part 4

4.2 Documentaries (1941-43)

4.3 [My Darling Clementine (1946)]

4.4 When Willie Comes Marching Home (1950)

4.5 This Is Korea! (1951)

4.6 What Price Glory (1952)

4.7 Summations

1. Ford At Fox

17 May 2013. This is a good moment, even a good week, to look swiftly over the whole Ford At Fox project, for on this date in the New York Times Dave Kehr wrote, “Fox has one of the best archival operations in the business, as can be seen in the superb work the studio did on the landmark John Ford box set, “Ford at Fox,” released in 2007 and still a triumph of the DVD medium.” [1]

Kehr’s is a good assessment. After writing the first review, where I thought Fox had not done right by simply going with the print of 3 BAD MEN which they had used back in the seventies, I found little or nothing seriously wrong with the actual restoration work – although sometimes the presentation on DVD left something to be desired and certainly Fox could have included some titles that it determined not to. A great deal of the restoration work was not done specifically for this Fox project (especially the Will Rogers and Shirley Temple films) and sometimes recycling already-released restorations with no written update or reconsideration was not the best plan (The Iron Horse, My Darling Clementine). New, better and more pointed commentaries for every film would have greatly benefited the series. That is, given the general excellence of the product, there seemed to be more penny-pinching than such a significant release warranted, and not enough input from some of the critical and scholarly talent they could have called on.

2. Ford at war

For Ford himself at first it seems that the war changed everything, that from this point “the guilt, paranoia, and irrational momentum of war” [2] never let him go.

“[War] was my racket for a while, and there wasn’t anything funny about it. I wonder what s.o.b. will be the first to make a comedy about Vietnam?” (Ford in Bogdanovich, p. 89).

“Whatever else war might be, Ford tells us [in The Battle of Midway], it is regardless an ultimate sort of experience of one’s life. What is life, or love, or death compared to it?” (Tag Gallagher, p. 236)

“of the thirty-three films made after 1948, eighteen are directly concerned with studying the problems of military communities, while nine others treat, in much the same terms, quasi-military communities (wagon trains, missionaries, political parties, police), while two others have military life as a background (The Searchers, Donovan’s Reef).” (Gallagher, p. 282)

However, war in general and military experience on active service in particular are significant topics in many Ford films prior to his service in the Second World War. In the Ford At Fox set these issues are to the forefront at least in Four Sons, Born Reckless, Pilgrimage, The Seas Beneath, As The World Turns, and Wee Willie Winkie before the period covered by this section of the review.

Like many others who saw active service during World War II, Ford came home with a specific freight of experiences, mostly undigested. The aftermath of Second World War may have furnished Ford with an audience receptive to military stories as well as providing that personal motive for their production. In the years that followed he had to come to terms with his wartime experiences within the context of a world at once changed and unchanged by the war and which, in its turn, continued to generate unsettling events apparently even more rapidly than before.He returned to work in an industry in the process of being pulled apart. Although he took (somewhat complicated) positions in the political events of those times, he was also an actor in the industrial restructuring that began with the United States Supreme Court’s “Paramount Decision” in 1948, which effectively ended the vertical monopolies that the major motion picture studios had enjoyed until that time. He worked out his contract at Fox, depriving himself of the security and infrastructure that the studio had provided as well as its interference, indifference and corporate direction. In its place he started his own production company, Argosy, and experienced the instability and penuriousness of being on his own as well as the freedom to fail on his own terms and to succeed on the box office drawing power of others.

If “guilt, paranoia, and irrational momentum” are characteristic of war, they are also appropriate to the American experience, and to Ford’s experience in particular, in the first decade following the end of the war.

[1] I have Jonah Goldstein to thank for drawing my attention to Dave Kehr’s article, “Dusting Off Items In Fox’s Attic” in The New York Times for 17 May 2013, which I had every reason to have read without his having to point it out for me. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/19/movies/homevideo/inconsistent- quality-from-fox-cinema-archives.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

[2] Rory Stewart, “Lessons from Afghanistan” New York Review of Books 18 August 2012, p. 82.

‘Our job,’ Ford once told a newsman, ‘was to photograph both for the Records and for intelligence assessment, the work of guerillas, saboteurs, Resistance outfits . . . Besides this, there were special assignments.’ (Bogdanovich, p. 132)

The World War II documentaries included in the Ford At Fox set are to be found on the disc titled Becoming John Ford under the menu heading “Special Features” and then, under the “Special Features” menu, “WWII Documentary Short Subjects Directed By John Ford”. This heading is not, strictly speaking, accurate because the long version of December 7th, credited to Ford and Gregg Toland, is not included. Sex Hygiene, definitely a documentary made by Ford, was completed and released in 1941 before Pearl Harbor and is, thus, not a “WWII Documentary Short”. Another documentary, We Sail At Midnight (1943) is sometimes credited to Ford but, according to Tag Gallagher, “attribution to Ford is very dubious” (573).

Sex Hygiene (1941)

“I looked at it and threw up.”

Made before Pearl Harbor, while Ford was still working at Fox, covered here for the sake of convenience.

Darryl Zanuck was a reserve officer and he said to me, ‘This would just be for the Army – but these kids have got to be taught about these things. It’s horrible – do you mind doing it?’ So I said, ‘Sure, what the hell, I’ll do it.’ And it was easy to make – we did it in two or three days. It really was horrible; not being for general release, we could do anything – we had guys out there with VD and everything else. I think it made its point and helped a lot of young kids. I looked at it and threw up. (Ford in Bogdanovich, p. 80)

This is the sort of film you would expect to find on the internet in countless downloadable iterations. However, the quick and superficial searches which I have made have only come up with a few images (one of which graces the previous instalment of this review) and not one YouTube, download, streaming, or the like video. So I guess those of us with strong stomachs should be sorry that it was not included in the Ford At Fox set.

And, since Sex Hygiene seems to have been another instance of a successful Zanuck-Ford collaboration, it is even more of a pity that it was not included.

The Battle Of Midway (1942)

“I [shot] all of it – we only had one camera.” (Ford in Bogdanovich, p. 82).

America’s first war documentary (it received the Academy Award as such), filmed during the actual battle. Although he was wounded in the first attack, Ford continued to photograph the events himself. (Bogdanovich, p. 132)

It [The Battle of Midway] is even a sort of autobiography, for war is an extension of one’s cognition, down toward hell, up toward heaven, and broadly across a horizon no longer two-dimensional. (Gallagher, p. 237)

Never was Ford to make a film more cinematically and formally perfect than The Battle of Midway. The concision of its seventeen minutes never demands concession to amplitude. (Gallagher, p. 239)

I cannot imagine any improvement on Gallagher’s scrupulously detailed and characteristically eloquent analysis of this film (pp. 236-245). Additional footage shot for the film is also included on the Becoming John Ford DVD and, as is usually the case with such footage, there is something to be learned from comparing it with what was actually used.

Torpedo Squadron (1942)

The dead return

Just before the battle of Midway, a photographer in Ford’s unit took some 16mm colour footage of life on a PT Boat – Torpedo Squadron 8. When all but one man in this squadron were killed during the battle, Ford had the footage edited and reduced to an 8mm film to be seen only by the families of the dead boys. Prints were delivered to them by personal envoys (such as Joe August) and the film was never used for any other purpose. (Bogdanovich, p. 132)

Despite its apparently private purpose, the film appears along with The Battle of Midway and the short version of December 7th on the Becoming John Ford DVD in the Ford At Fox set. The squadron memorialised in this way was destroyed in the Battle of Midway and the footage is thus something of an appendix to Ford’s cinematic memoir of the battle. I feel an uneasy sense that a particularly important privacy has been violated by exposing it to the public.

December 7th (1943)

An Academy Award-winning documentary about the bombing of Pearl Harbor. According to Ford, his unit arrived about six days after the attack. ‘Gregg Toland directed that,’ he says. ‘I helped him along, I was there, but Gregg was in charge of it.’ (Bogdanovich, p. 132)

Bogdanovich’s account belongs to a more innocent age. It is now accepted that there were two versions of this film – one feature-length and one a little over half an hour (34 minutes, to be exact). The latter was the one (finally) released, the one that won the Academy Award. The DVD included in the Ford At Fox box set contains only the shorter version – although Ford gave a print of a longer version to the US National Archive in 1946 and it has been released on DVD. [1] Two iterations of the longer version can be viewed at the US National Archive site [2] , and I have found instances of the film in different versions on YouTube.

Much of the movie, December 7th, was eventually shot at Fox, with Ford and Toland co-credited as directors. For reasons that remain cloudy, the film was confiscated and Roosevelt issued a directive subjecting all future Field Photo material to censorship. (Gallagher, p. 246)

There would seem to be a rebuke implicit in President Roosevelt’s directive, just as there is something that looks awfully like prototypical producer interference in the “coda” to The Battle of Midway, “added at FDR’s request, [that] swishes paint across three successive signs tabulating the Japanese vessels destroyed” (Gallagher, p. 244). In time Ford came to dislike Roosevelt intensely.

December 7th was apparently originally intended as a report, “a complete motion picture factual presentation of the attack on Pearl Harbor” (Frank Knox, Secretary of the Navy) [3] . I say “apparently” because (1) intentions are not always easily discerned at the best of times, (2) in a wartime bureaucracy it is even less easy to track intentions, and (3) Knox was a Republican (as was Ford’s OSS boss, Wild Bill Donovan) whereas the President at the same time was a Democrat. At any rate what eventuated was rather more of a tendentious argument, a piece of oratory, than the dry documentation expected of an investigation. It seems a reasonable assumption that the Presidential directive cited by Gallagher represented the administration’s negative response to the long film’s argument.

In 1943, Ford and Robert Parrish eliminated December 7th’s fingerpointing, changing it from an investigation to a paean of the navy’s ability to bounce back. . . . It was screened, and it won Ford his fourth Oscar in a row. (Gallagher, p. 249)

It is impossible to deal properly with the short version included in the Fox At Fox set without taking the long version and the controversy surrounding it into account – and this is why it is such a pity that the long version was not included in the set. In order to offset that absence somewhat I am afraid I am going to have to spend more time and use more words than perhaps any of us would like.

Today the long version is a troubling and troubled film, difficult to read, while the short version is none of those things. Yet the long version is the parent of the short one: the latter is crafted entirely of the body of the former and preserves portions of its sense as well.

At least two different versions of what I have been calling “the short version” are currently in circulation. The one included in the Ford At Fox box set seems to be the one which won Ford another Academy Award; and I shall call it the “authorised” version from this point on. Another short version seems to have been included on the same DVD that contains the long version, but this impression is misleading. What the chapter menu for that DVD calls “the censored version” is actually only the last 42 minutes of the long version encoded on the disc. Nothing has been “censored” from that footage; in fact, it contains 8 minutes more than the authorised version. The authorised version also contains at least one shot from the long version which does not appear in the censored version.

Actually the differences between the long and the authorised versions of the film are instructive, and those differences are obfuscated if the viewer gets the idea that the last 42 minutes of the long version are the same film as the 34 minute version that won the Academy Award.

Here is a summary of the authorised version.

December 7th (1943).

Introductory sequence. Terror music. Ship, plane destroyed. “Your War and Navy Departments present December 7th”. Pan down to V shadow and Navy cap. Victory music. Black screen.

Opening. Palm trees: The narrator [4] : “Early Sunday morning …”. The initial argument stresses that adequate precautions had been taken against sabotage which the military had repeatedly warned was a danger. Sunday morning as usual. Field mass subsequence: Christmas is coming says the Chaplain. Radio message unheeded.

Attack. 7:50 am, the attack begins. Planes. Washington and the Japanese envoys. Cut back to planes. “They knew that our task forces were at sea, they knew their disposition, they knew too that no long distance airplane reconnaissance, no inshore airplane patrol, was being maintained”, etc. That is, the attackers had a great deal of information about their target. However, the opportunity to say directly that this information may have come from spies is not taken, and the phrase “favoured by our lack of readiness” suggests instead that American policy may be to blame. The attack sequence is long and apparently quite detailed. “By 9:45 the attack was over. One hour and fifty minutes of perfidy.” These words come to an end pretty much precisely 17 minutes into the film – that is, halfway through.

Aftermath. The dead. Their voice from the grave (Dana Andrews). Memorial service (including ribbon from Gold Star Mothers). “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” sung by an invisible African-American (?) male. Reappearance of Chaplain from the Sunday morning service as mourner. Fade to black around 24:14.

Lies and Truth. “Tokyo is calling Nagasaki, Kobe, Otaru”. Debate begins. “Mr Tojo”: “The aircraft carrier Enterprise, capsized and lost”. Narrator: “Incorrect. That’s the old target ship, Utah.” And so on. As the debate is concluded there is a shot of palm trees from beneath which recalls the “Early Sunday morning” shot. The camera pans down and left to reveal sandbags and an Asian soldier on guard. The “American schoolchildren” who go into “zig zag trenches” are mainly Asian, as is to be expected in Hawaii.

Section on Japanese in Honolulu. “Yes, your bombs, Mr Tojo, brought many changes, and in no small measure served to complicate the already complex life of the Japanese in Hawaii. As though to permanently erase their relationship with the homeland, they wiped out or removed every vestige of the written Japanese word. Closed are the language schools, empty and boarded up, the Shinto temples, gone the flag of the rising sun.” Visuals are about signs and writing.

Coda. Ironically the Japanese have not achieved what they set out to do much less what they claimed they had. The US has come back stronger than before and now Hawaii is on the alert. “For all that take the sword shall perish with the sword” are the last words of the narration, ending at 34:00.

This summary is intended to address two lines of argument which are highlighted in the long version but downplayed or absent in the authorised version. “The original eighty-three-minute version of the film argues not only that the military was caught off guard during the attack but also that it was blind to spying by much of the Japanese-American population of Hawaii”, McBride asserts (p. 354). That is, put in more report-like terms, both a lack of proper preparation and espionage by local Japanese contributed to the attack’s success.

Gallagher, however, makes a somewhat different claim.

Everyone who has written about December 7th, including myself, has assumed that the cause of official displeasure was the film’s bitter exposé of how administrative oversight had left Hawaii vulnerable. . .

Yet there is little criticism of the Navy in December 7th and, when a censored 34-minute version of the film was eventually released in 1943, at the Navy’s request, to be shown to servicemen and industrial workers, criticism was still there – the lack of reconnaissance patrols around Oahu, the grouping of planes at Hickam Field that made them easy targets . . .

The real reason for December 7th’s confiscation, then, was not its allegations of lack of vigilance, but rather a change in Roosevelt’s policy regarding the Japanese-Americans resident in Hawaii.

In Roosevelt’s judgment, the 110,000 American citizens of Japanese descent living on the West Coat were a terrible threat to national security. Accordingly, he [sic] had been interned in concentration camps, suddenly and brutally. Obviously, the 160,000 Japanese-Americans on Hawaii posed an even greater threat, since Hawaii was the most critical American base in the Pacific. Roosevelt wanted these potential subversives locked up as well, and the task of December 7th was to argue for this necessity by indicting the loyalty of 160,000 Hawaiian citizens.

But something rare in recent American history occurred. The military governor of Hawaii, General Delos Emmons said, in so many words, “Nuts, I won’t do it!” – and he prevailed. The Nisei stayed free. Accordingly, December 7th’s denunciation of their disloyalty was replaced with a tribute to their patriotism. And not a single hostile act by a Japanese-American was reported.

Hawaii’s successful defiance of Roosevelt is an ignored event in American history – not surprisingly, because it gives the lie to the excuse that continued internment of 110,000 people (mostly Californians) through almost four years of war (and the effective confiscation of their property to the profit of their neighbors) was an understandable precaution in the heat of the moment.

Ford and Toland, whatever their sentiments at the time, were following orders. A year after the war was over, in December 1946, Ford made a point of depositing in the National Archives in December 1946 an 82-minute print, unreleased (but now on dvd), containing Toland’s unreleased sequences preceding the 34-minute released sequences. As a single film it makes no sense: the second part contradicts the first, blatantly. Yet it documents a government policy that we have forgotten ever even happened. (Gallagher, pp. 246-247).

Gallagher presents a strong case for the effect of Hawaii’s special policy about internment on the administration’s attitude toward the long version of December 7th. However, the argument that this was “the real reason” for that attitude seems to assume there could be only one reason why the Roosevelt administration wanted the film shelved. And the idea that the long version “makes no sense: the second part contradicts the first” does not conform to my reading, at least. McBride’s summary, quoted above, more closely represents what I see and hear from the screen, although I do not believe it is entirely accurate either.

Below is Gallagher’s summary of the long version. I have highlighted in boldface the sentences which apply to the authorised version in the Ford At Fox set.

December 7th (1943 [5] ). Long version. On December 6, 1941, a character called “U.S.” — a traditionally garbed Uncle Sam (Walter Huston) — is musing about “Hawaii, Territory of Heaven,” but white-suited Mr. C (for Conscience: Harry Davenport) suggests U.S. is complacent. U.S. Narrates the cultivation of Hawaii, comparing it to the winning of the West. Sugar cane, pineapples, big business. From grass huts to modern Honolulu, its university libraries, schools, arts academy, streets, homes, trees, churches, 248 hotels, beaches, ports (typically repetitive: e.g., not one exemplary church, but eight different churches), businesses. “The Big Five” companies: “Castle & Cook, Alexander & Baldwin,” etc., “the nerve center… of the territory. Grandsons, aunts, held together by blood ties and interlocking directorates. Scratch one and the other bleeds.”

But, says C, the laborers are mostly Japanese, 37 percent of the population, at work in fields, restaurants, flowermarts, their streets, slums, Japanese telephone book, magazines, banks, their own “Big Five.” Thirty two(!) Japanese shop signs, with superimpressions of street life. Japanese boy scouts salute the flag. But the Japanese language is taught, too, “along with their morality and their culture” and their Shinto churches. Declares a monk [or “priest”, Philip Ahn]:

⁃ In Shintoism we worship the first Japanese emperor, whose creation started the world of mankind. … [Gallagher: Emperor Hirohito] is the mortal image of our immortal deity. … Shintoism preaches honor of the ancestor, thereby keeping alive the fires of nationalism and preserving a racial and social bond with the unbroken and divinely descended Imperial dynasty. To be a Shinto is to be a Japanese. This is not, nor can it be, a matter of choice. It is a duty.

Seventeen thousand Hawaiian children are registered for Japanese citizenship; the consulate carries on extensive espionage. We see various eavesdropping Japanese: a gardener outside a men’s room, girls in a barbershop, a chauffeur, a girl on a date. A Nazi tells the consul how overheard club talk helped him sink a destroyer (a frequent “plot” in propaganda films).

But U. S. remains optimistic. Nine lovely girls represent minority groups; children perform ethnic customs; six girls say “Aloha.” But U.S. dreams of the war in Europe. And, Sunday morning, the squadrons appear, “swooping down like flights of tiny locusts,” as Japanese envoys confer in Washington. Ten minutes of battle footage. Fifty of two hundred planes are downed, but 2,343 Americans die. The camera frames a grave. “Who are you boys? Come on, speak up some of you!”

A voice identifies itself as Robert L. Kelly, USMC. We see his picture on the wall at home. He comes from Ohio, he tells us, and introduces his parents. The same voice continues through six more dead soldiers, each representing different services, different regions, different racial origins. Iowa parents pose American-Gothic-like before their silo; a black mother hangs laundry. “But, how does it happen that all of you sound and talk alike?” “Because we are all alike. We are all Americans.” Notably Fordian is the funeral held on a shore midst white sand and flags (terribly beautiful photography). A tenor sings “My Country ’Tis of Thee”; an elderly officer and wife stand in attendance, she struck with such fragile sorrow that, though it looks actual, one suspects Ford posed her in his patented way; tracking shot looking up at palm trees.

From a map of Japan a radio tower arises, a Godzilla-like monster sprouting waves: our narrator corrects Tojo’s victory claims. Before-and-after shots chronicle salvage operations. “Who is that saucy little girl…? [A small ship sailing past.] By George, it looks like…Yes! It is! The mine-layer Oglala…!” Now Hawaii prepares for attack. Barbed wire, tunnels, drills, children in gas masks. Some Japanese buy war bonds; others are forced out of business, others arrested. But not a single act of sabotage. All traces of Japanese language are removed, all those signs changed, temples closed.

In Arlington Cemetery a Pearl victim talks to a Marine casualty, who points out where everyone’s buried. “I saw the General the other day,” the marine says, meaning George Washington. The World War I vet is cynical but the marine says, “I’m putting my bets on the Roosevelts, the Churchills, the Stalins [6] , the Chiang Kai-sheks!” Twenty-four UN flags pass in review. (Gallagher, pp. 247-249)

A comparison of the two summaries, mine and Gallagher’s, supports the latter’s contention about how the Japanese in Hawaii are treated in both films. The long version does contain quite a lot of words and images which argue that the Japanese in Hawaii are untrustworthy and dangerous enemy aliens, whereas the authorised version is parsimonious and positive in its references to the same group. However, it is also the case that both films contain criticism of the military response and overall preparedness, although the long version lays the blame ultimately on the government and “the people” (in the person of Uncle Sam) for adopting an attitude of appeasement. This is an issue that Gallagher’s summary does not address.

But if we accept, as I do, that Knox’s brief was the basis for making December 7th in the first place, military preparedness was what the film was intended to investigate or document. On the face of it, this is rather a strange goal for a motion picture as distinct from a written report. Presumably such an investigation is bound to be a contentious one with a potential for depressing public morale. The circulation of reports is routinely limited, whereas films are always made for wider audiences and generally for the public at large. To specify that the investigation be represented in a popular or mass medium suggests either that there will not be a thorough investigation or that the film is deliberately intended to question the United States’ military preparedness and, in the process, to upset the public at large. That is, Knox’s request, coming as it does from a prominent Republican advocate of preparedness in the year following Roosevelt’s 1940 Presidential election victory, is a disingenuous one: no “factual presentation” was intended as the result, instead the film was intended to argue the case that the military services, and the United States in general under the policies of the Democratic administration, were unprepared for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

McBride asserts that Gregg Toland (“director and cinematographer”) and Samuel G. Engel (“writer-producer”) were the team principally responsible for the long version, with Ray Kellogg providing miniature work (pp. 354-355). Gallagher only credits Engel as “crew”, but gives George O’Brien and James K. McGuinness credit as “narration writer[s]”. He also credits Kellogg with second-unit work and claims that “[a]ll the battle footage (accepted as actual for years) was staged by Toland and Ray Kellogg, mostly at Fox, using rearscreen” (fn. 355, p. 632). Robert Parrish, who edited the authorised version, is cited by McBride as claiming that it was only after Ford went to Pearl himself that the director “discovered that Toland and Engel had concocted an ambitious but bizarrely misguided scheme to turn December 7th into a feature-length hodge-podge of documentary and dramatization” [7] (pp. 354-355).

Now Parrish, by his own admission, broke with Ford over a conversation about Parrish’s Oscar for Body and Soul (Rossen 1947), in which the Oscar for the authorised version of December 7th played a part [8] . He confesses that he idolised Ford and, from his story about what he did at Ford’s behest during the editing of The Battle of Midway, one suspects that while he was working on December 7th he routinely believed everything Ford told him. He has also proved to be an imperfect witness of what happened on the set during Drums Along The Mohawk (see part 3c of this review). I suggest that the story about Ford’s unearthing Toland and Engel’s “bizarrely misguided scheme” and Ford’s concern about the content of what they may have been producing is one that only a bunny would have believed. Parrish seems to have accepted that the result of Ford’s concern was that he spent some time in Hawaii shooting scenes, got himself kicked out, told Toland and Engel to work undercover and then to “keep up the good work” as he left – not, I submit, a very reasonable course of action to scupper a misguided scheme. It really makes a lot more sense to think that, following Knox’s brief and in line with what Donovan wanted, Ford was thoroughly aware of, believed in, and may even have spelled out the “message” of the long version as well as the revisionist “message” of the short. I think December 7th is a “John Ford film” at least as much as The Grapes of Wrath is a “Darryl Zanuck film”.

The long version of December 7th then, is interesting to this project for what it says about the figure I have made around the words “John Ford”, and the authorised version mainly for what it suggests about what remains of the director’s vision when it is drastically re-edited in accordance with demands other than those which originally inspired it.

It is characteristic of wartime documentaries that they are overt propaganda, but it is also the case that propaganda is a determining component of many documentary films and that analyses of some methods of propaganda are often employed in interpreting documentary films. Propaganda, more or less concealed, is also a feature of many fiction films. At least one such Hollywood film bears an interesting, doubtless coincidental, relationship to December 7th – the 1933 MGM release, Gabriel Over the White House (La Cava). Walter Huston is a heavily figural presence in both, and political speech-making about American government policy is characteristic of both. More to the point, both are clearly didactic allegories rather than reportage or entertainment and both are critical of the course that the government of the United States has taken. Gabriel Over the White House called for a visionary President to assume dictatorial powers for the good of the nation, and it specifically stressed an enhanced and pre-emptive global military posture. The film was known to be a favourite of the Roosevelts’. It is worth noting that this unusual, tendentious film was made for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and intended for widespread theatrical release, and thus some of what seems strident or even avant-garde to us today about December 7th may not have been quite so striking to audiences in 1943.

It is also the case that the paradigms of textual analysis employed in a great deal of film criticism in general, including mine, are drawn as much from (Continental ideas of) rhetoric as they are from (Continental ideas of) narrative or literary discourse in general. Inevitably (for me) much of what I have been writing about Ford’s films has treated them as arguments or quasi-arguments (“thinking”) in which narrative elements, stylistic markers, certain images (“figures”) and so on, are significant mostly insofar as they contribute to a particular (“Fordian”?) way of making sense of things, which, if I am lucky, you will think of as “Ford’s vision”.

At any rate, the long version of December 7th is an overt exercise in moral suasion rather than a dispassionate investigation. The film gives prominence to three highly-stylised debates rather than taking the form of an enquiry. These debates take up almost all of the first half of the long version and its coda – which is to say most of what has been cut from the authorised version. The long version is also of specific interest for the means by which it represents those arguments, and for the repellent nature of some. Twice decent people who are clearly “on our side” argue with each other about the immediate past and the future, at times in ugly terms acknowledged by the speakers. This film is quite deliberately a slippery object in which different points of view are exposited at length and dishonestly.

The debates

– Mr C versus Uncle Sam

The long version of December 7th begins with a long debate between two figures, Uncle Sam (Walter Huston) and Mr C, for Conscience (Harry Davenport). That is, at the beginning we are placed within a fiction that is not a story (or, at least, not much of a story).

Uncle Sam, we are told, is in Hawaii to escape from the tensions engendered by America “making up its mind”. The first shot of this debate is a tight close up of the face of “Miss Kim”, lushly lit and with glowing lips, reading back Uncle Sam’s dictation in a heavy Asian accent. The words have to do with the “tropical beauty” of Hawaii – “not excluding the opposite sex”. We know this situation – the ageing boss ready to let his hair down and have some fun and the hot, exotic secretary there to fulfil his every wish – but does it belong in a documentary about the attack on Pearl Harbor? That kind of movie wouldn’t be about a May-December love affair; it would be about Americans and Asians fighting each other. Indeed. And this is where we might begin to think about the implications of the figuration of desire in this movie.

At another point during these preliminaries Mr C claims that what he says is “as factual” as Uncle Sam’s claim that the Hawaiian “air is filled with the scent of a million flowers” – a warning to those with the ears to hear it that there will be no “facts” in this exchange, only assertions. The “fact” here is that two points of view are disputing for our acceptance, two positions are being performed cinematically. Beyond this there are no “facts” at all, only unverifiable, questionable, words and images.

It is a situation that any viewer of Judge Priest or Young Mr. Lincoln ought to recognise – and it is wise to keep in mind the visionary ideas of truth, justice, character and argument that suffuse those sequences when considering this one. The antagonists are in some ways more complex, or conflicted, than the opponents in the other films. Uncle Sam, an idealist, does not seem to be vouchsafed the clarity of vision that characterises Priest and Lincoln, although he does share their tolerance and goodwill. Indeed, Uncle Sam is a deal too self-indulgent and expansive: he is unwilling rather than incapable of recognising the danger Hawaii is in. Mr C, on the other hand, does exhibit Priest’s and Lincoln’s dogged persistence and their sense of the urgency of the situation, as well as a great deal of their rumpled, shyster folksiness – but he may also seem to be acting like a paranoid and cynical misanthrope.

The (fairly long) “spy sequence” which climaxes the debate between Uncle Sam and Mr C consists of staged footage using “Japanese” – that is, Asian – faces (taking pictures, driving cabs, working in beauty salons, etc) with voice over dialogue suggesting that these are the faces of agents gathering intelligence and spreading disinformation. One wonders just where these images were shot (Hawaii or L.A.), what was told to the people who appear in them during the shooting and how their cooperation was enlisted. Gallagher and others have remarked that Fox soundstages were used to add drama (fiction) to the sparse actuality footage of the attack, but these shots serve a different, more malign, purpose.

This sequence is the crux of the film, even though near the end of the debate Mr C concedes that the danger it asserts has been taken into account in the United States’ military planning (“The Army and Navy have been aware of the Japanese spy activities for years. They even have a little black book, a grab list, of all suspicious persons if and when trouble starts”). It is the crux of the film because it is the climax of all that Mr C has been warning Uncle Sam about. Mr C has mounted an argument grounded in the ethnic variety of racism that Ford espoused. He asserts that Japanese culture, and specifically its religion, demands loyalty to Japan above and beyond any loyalty to the United States (an argument one would have thought would have given a practising Roman Catholic a guilty twinge, especially one as versed in American history as Ford was). Children, some pledging allegiance to the US flag, some absorbing Japanese culture in language schools, are shown in a way that seems to stress the similarity of the two activities and the triumph of the latter.

This argument is never repudiated by the film in either version (and, to be fair, is hardly presented in the authorised one). Both versions do attribute some of the devastating success of the attack to intelligence. And there is one shot which appears in both versions and is the subject of the same direct narrative comment in both that obliquely confirms Mr C’s racist stance even as the film in both versions appears to be modifying it.

“This young American Japanese gave the best illustration that over Hawaii the rising sun had begun to set”. Really? Who would believe in the loyalty of someone who can so quickly switch a Japanese war slogan to an American one (especially when that war slogan had been recently heard in the film as the sound of triumphant Japanese propaganda)?

Racism is not the only ugly factor here. Walter Huston’s Uncle Sam is drenched in images of seductive women when he makes his final case for “a melting pot in which everything literally melts”. That is, it is suggested that women, seduction, desire, are principal means for undermining American security. This is what Uncle Sam sees “with [his] head buried in the sand” (Mr C), and just before he has his “nightmare”, which prefaces the film’s account of the actual attack and its aftermath. John Carpenter’s Hallow’een (1978) is not more explicit in making a significant connection between (hetero)sex and violence.

The end of this debate suddenly switches ground when Mr C concedes that the military are indeed fully informed and could be fully prepared; what is missing is a popular will to fight.

Washington’s on to Mr Hirohito and company, but Washington has its hands full trying to keep the isolationists from disbanding the Army and at the same time trying to put our factories on a war footing. So it’s just a case of letting the Japanese push us around until you [Uncle Sam], every a hundred and thirty millionth part of you, provide Mr Roosevelt, Mr Stimson, Mr Hull and Mr Knox with good size clubs to back up their words with actions. . . You want peace but you want it the easy way. You want to go on leading your own way of life but you don’t want to fight for it. And if anyone suggests doing something about it – hah! – he’s called a war-monger. Watch out, U.S., some day one of these “incompetent, stupid little children of the Orient” will choose you – and when they get ready to square off, they won’t worry about offending you; they’ll pick their time and their method, and they’ll come over here, and they’ll blow that bastion of military might behind which you sleep so easily into smithereens.

According to Mr C, in Uncle Sam’s world the attack on Pearl Harbor, or something like it, has become a necessary precondition for war (a criticism of Roosevelt’s policy which would resurface in later years). The rather unexpected and harsh condemnation of the people of the United States, “every a hundred and thirty millionth part of you”, was dropped from what was finally released, and that circumstance surely does allow some credence to the notion that the film’s criticism of American policy (under the smoke screen of a figurative representation of the American people) may have been one of the things that got it into trouble in the first place. What Mr C favours is a policy of pre-emptive action – not unrelated to the policy that has been followed by the United States since the end of the Second World War, with results we continue to experience today. This is the foreign policy to which Ford himself certainly adhered after the war, and which became the cornerstone of his anti-communist conservatism. [9]

The narrative outcome of the argument between Uncle Sam and Mr C is that the former has a nightmare which the narration for the authorised version claims was an accurate representation/recapitulation of the events of 1941 short of Pearl Harbor, and surely a premonition of the attack as well. Mr C’s bleaker vision of the state of the world would seem to have prevailed.

However, in the course of this debate the focus has been shifted away from American military preparedness or the lack of it and onto spying by the Japanese in Hawaii. We ought not to be surprised by this, since Donovan’s OSS was the branch of the administration tasked with making the film and it was in the interests of this new branch of government to emphasise the importance of its area of activity and the apparent failings of the FBI in policing such matters. Mr C’s argument is that the Japanese, as a people, as a race, are untrustworthy and disloyal. So much time is given to this argument, and so sensational are the words and images associated with it, that any other arguments are overwhelmed. In addition when the attack comes, some of its success is directly attributed by the narrator, whose “voice of truth” has taken control of the images of the film, to Japanese espionage. Mr C has prevailed rhetorically as well.

What is upsetting about these outcomes is that the more or less even-handed multi-culturalism often displayed in Ford’s fiction films seems to be exposed as a pose, for although a great deal of time is spent showing Uncle Sam’s argument for tolerance and fairplay, little or none of it is validated. His images and words are a delusion, at best an insignificant part of the truth (they are, indeed, history as legend), whereas Mr C’s are not. Hawaii might be the proto-America Ford celebrates in Drums Along the Mohawk but it is not, and that is apparently because of the Japanese. That is, the film is dishonest and racist, and its existence reminds us that Ford was often dishonest and racist as well.

There is an apparently liberal, tolerant “Fordian” sequence which is identical in both versions of the film – one that perhaps prefigures some of the avant-garde theatrical artifice of The Battle of Midway. Representatives of the soldiers and sailors who died in the attack on Pearl Harbor are summoned to identify themselves on the soundtrack. They all speak with the same voice, Dana Andrew’s, although they are from different, easily identifiable ethnic and regional backgrounds – and they say they speak this way because “we are all Americans”. Here the message would appear to be the same as that of Drums Along the Mohawk – but in no version of December 7th, are there any Japanese, indeed any Asians, among the military dead; and although civilians are shown injured during the attack, the film says nothing about civilian deaths either, presumably because to do so might raise the question of how the attack had impacted on the 37 percent of the population of Hawaii who were Japanese-Hawaiians [10] .

The attack, or rather “early Sunday morning”, the prologue to the attack, marks the place where the authorised version begins. It seems to me that actually there is nothing in the authorised version which contradicts or conflicts with the racism presented in the long version. It is the long version that asserts that there were no acts of sabotage, suggesting that the military alert in effect was wrongly focussed on the local Japanese community and not enough on a possible threat from outside. The authorised version merely reproduces those lines – in the same cursory tone. It is the long version that describes how the situation of the Japanese in Hawaii changed as a result of the attack. Indeed, editing the authorised version down to 34 minutes allowed Ford and Parrish to take out some of the strongest pro-Japanese-Hawaiian footage, representing the community’s tangible support of the war effort (see Gallagher’s summary and my [lack of] emphasis above).

– The narrator versus Tojo

The debate motif resurfaces after the “rollcall of the dead” sequence when the narrating voice of the documentary directly challenges a “Japanese” accented voice that the former calls “Mr Tojo”. Here the cards are obviously stacked in favour of the American narrator, the voice of truth in most documentaries and newsreels. In the long version the parallel between the previous debate is instantly noticeable, but in the authorised version the ground for the narrator’s suddenly breaking the glass wall of the genre and becoming a character in a fictional debate is laid by the flashy artifice of the preceding rollcall sequence.

In this debate, as in the previous, the participants apparently command both words and images. “Mr Tojo’s” voice is greeted with a “banzai!” cheer. Shortly after, it misidentifies the image it has summoned on the screen as a ship that was not sunk in the attack – or so claims the American narrating voice in a kind of meta-misidentification. For of course all the sounds and images in this debate have been put there by the film makers, not by either of the voices in the film, just as the sounds and images attributed to Uncle Sam and to Mr C are not “theirs” but those provided by the authoring writing of the film. In this instance, however, the fact that the apparent argument is no argument at all is cause for various triumphant assertions instead of something buried or elided or obscured by the text’s presentation as a dramatised debate.

– The sailor versus the World War I veteran

Dana Andrews appears visually as well as aurally – and again as the all-American living dead – in the long version’s final debate. This exchange takes the form of an extended exchange staged in Arlington Cemetery, carrying clear overtones of the opening debate between Uncle Sam and Mr C. I think that Gallagher’s identification of the two figures in this debate in the summary of the long version above is not quite right. Andrews is a sailor, not a marine, and his opponent (Paul Hurst), whose face we never see, may be a marine, but is more definitely just one of those unknown foot soldiers who died in the First World War. They are dichotomous representatives of youth, age and their respective branches of the military (sea and land), as well as of the casualties of each war.

The debate itself appears to be another argument between idealism (the sailor’s claim that this war will indeed end all wars) and paranoid cynicism (the veteran’s “heard it all before” response). The veteran explicitly shares Mr C’s distrust of the common people. An extended, and slightly zany, baseball metaphor underpins their argument and has the effect of highlighting its fictionality. Then: “Six will get you twelve that fifteen or twenty years from now they’ll be opening up new sectors in here,” says the veteran. (He is too optimistic; in 1950 the United States went to war in Korea). And Andrews goes into a peroration: “I’m puttin’ my dough on a ballslugger called Reason, on a pitcher called Commonsense, on an outfield called Decency. Faith, Brotherhood, Religion, teams like that, are warming up all over the globe. They’re in spring training now but when the season starts they’re gonna be all out there slugging, pitching, fielding their way to a World Series pennant called Peace”. “Yes, all over the world!” chimes in the narrator, as a montage of flags begins, “in Australia! Belgium! …” and so on as a male chorus sings about “united nations on the march” until a fighter plane writes a white V in the sky, complementing, rewriting, the black V shadow which opened the (long version) film. [11]

This outcome surely invites understanding the argument of the film as a whole as vindicating Uncle Sam’s tolerance and hope. That is, it tends to reverse the outcome of the first part of the film, in which Mr C appears to win the argument. But although the long version of December 7th is rhetorically crude in the way in which it stigmatises one racial/ethnic group, loads its arguments against Japanese propaganda, and inflates an American sport beyond all reason and commonsense – not to mention its continuing and obvious recourse to fiction as a means for understanding actuality – there is also one subtle strand of a kind we have seen before in Ford’s work.

For although Mr C wins the debate with Uncle Sam, the actual course of events in the attack and its aftermath goes some way to undermine his case, thus questioning the anti-Japanese rhetoric of that part of the film. According to the narrator, whose status gives what he says a great deal more cachet than either of the first two debaters, some Japanese in Hawaii did provide information used in the attack, but most proved loyal to the United States, and there were no acts of sabotage. Uncle Sam’s idea of Japanese Hawaiians seems closer to what the immediate circumstances of the attack revealed than Mr C’s idea does. To some extent, at least, what Mr C has been claiming finds not very much support in the attack and its aftermath. The question of Japanese loyalty raised by the first part of the film is still on the table at the end of the second.

At the end of the film, in the final part, or coda, the outcome would appear to be the opposite of what occurs in the first part – with the sailor’s passionate idealism winning the day this time. But the sailor, like Uncle Sam, is making an argument about something that has not yet happened. The difference is that at the end of December 7th we still have no idea of what the actual aftermath of the war will be, whereas the outcome of the attack on Pearl Harbor can be presumed to have been known even before the long version of the film was made, much less viewed. Neither the sailor’s faith nor the veteran’s cynical assessment of human and political failure has been put to the test. As in the first case, the winner of the argument may not prove to have made the most accurate prediction of events, only the most convincing case. Anyone viewing the film today knows that, no matter how many flags are flying and voices singing, the old veteran is right and the sailor is a fool. Would the response have been all that different in 1943?

A distinction is being drawn by the film between arguments based on (visionary) conviction and what actually happens historically. Effective, convincing arguments are not always predictive of historical outcomes, but equally, the actualities of history do not necessarily vitiate the authority of an argument based on vision. That is, we are in the “print the legend/this is what really happened” territory of Fort Apache and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence. If what I sense about the film is indeed the case, then it is a very good example of Ford’s commitment to the conviction of immediate experience. What is left unanswered by this strategy as applied to the nonfiction referent of December 7th is the question of what is to be done when the legend is a foul, corrupting lie.

The long version is supposed to be 82 minutes. The “censored” version is 42 minutes. This means that about 40 minutes is spent in the Uncle Sam/Mr C debate. By my accounting, this debate is the longest single section of the film. The attack and its aftermath make up another section (all the material in the authorised version plus what was cut from the long version’s “retraction” of Mr C’s anti-Japanese-Hawaiian stance). The sailor/veteran debate in the Arlington Cemetery would be the final section or coda.

I believe I have made a case for believing that the long version does put forward certain criticisms of the nation’s “preparedness” and that those criticisms do constitute reasonable grounds for the Roosevelt administration’s reluctance to release the film. But I think that the arguments Gallagher outlines also played an important part in its “suppression”. First, I think that the jingoistic hatred of the Japanese displayed in the long version made some in the government uneasy. Supporting evidence for this may be adduced from the delay in releasing Frank Capra’s Know Your Enemy–Japan, which pretty faithfully follows the line set down in the long version of December 7th. [12] Second, December 7th in its long version tacitly raises the question, “if the Japanese in Hawaii are so terrible why aren’t they all in concentration camps like the ones on the mainland?”, a question that the Roosevelt administration did not even want raised, much less answered.

Authorised Version

The authorised version runs 8 minutes less than the part of the long film covering the same events. The re-editing was not quite so simple as cutting two sequences from the last 42 minutes of the long version (for example, a few lines of narration had to be (re)written and (re)recorded), but that description is pretty close. Certainly it was not at all the careful excision and fiddly reconstruction that seems to be implied in some accounts of the process of change.

That is – assuming that the print Ford deposited at the archive was in fact the long version before Ford had made any substantive changes to it. There are some circumstances that suggest a least one substantial change may have been made before the long version we now possess. McBride, presumably following Parrish, claims that Budd Schulberg and James Kevin McGuinness were hired to write “a new narration”, presumably to replace the one provided (or merely suggested) by Toland, Engel and/or George O’Brien (p. 385). In point of pure fact, there are only a few lines which differ from the existing long to the existing short version, so a professional two man team of rewriters seems like overkill if what they were to rewrite was the narration of that long version. On the other hand, I cannot find any reference to a script of an earlier narration – which, if it did exist, would of course provide a good deal of weight to claims that Ford did or did not make substantive changes to what had been done under Toland’s supervision.

All of which is to say that the relation between what Toland “directed” and what Ford “directed” remains cloudy. What is certain is that Ford can be placed at a key, gate-keeping, point for each version: the man who deposited a print of the long version at the archive, and the man who at the very least produced and supervised the short version. Parrish claims that Toland was so upset with the reaction to his original film that he asked to be re-assigned to Rio. It is also a matter of record that Toland never worked with Ford again, even though he is said to have been asked to at least twice by the director.

Close analysis 1: four shots in the authorised version

Immediately surrounding the attack, four shots are of particular note, all of them images of Asians supposedly living in Hawaii and, I would argue, all supposedly Japanese.

1.

The shot from which this image is taken occurs in the short “authorised” version of December 7th. This man is shown cutting vegetation and looking out over a harbor during the “Sunday morning” preliminary to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Like the two images of Asian faces which follow, the man seems to be there as a witness to events which are, in this case, just about to happen.

The shot from which this image is taken occurs in the long version of December 7th. This shot is longer than its counterpart in the authorised version, and it “shows” more. In the long version the shot is part of the lengthy and elaborate sequence on spying by Japanese-Americans which was cut from the short version; it does not appear in the “early Sunday morning” prologue to the attack. In the first scene of the long version devoted to espionage, a Japanese consular employee reports to his boss that “the sugar cane fields … have a fortunate proximity to Pearl Harbor”. Shortly thereafter, in a scene which also implicates Japanese-Hawaiian children in spying activities, the shot showing the man cutting cane appears, and he is shown to be observing the movement of a ship. Thus, this image, which in the authorised version apparently signifies only peaceful agricultural activity, to the film makers bore an additional inferential sense of local Japanese espionage.

To be fair, this image as all the images in all versions of this film, is historically complex – for presumably it does not depict a Japanese-American spy, but any-Asian-man-whatever, engaged by the film makers to chop vegetation against a harbor with a warship moving in the background. We do not know what this man may or may not have been told about his fictional role in this documentary; indeed, we do not know what pressures or incentives may have resulted in his appearance in the film. We do know, however, that his image was appropriated and re-appropriated into the film’s two differing systems of meaning, and that he appears first as a villain, then as a victim – that is, that the film makers treated this image (as they treated all the others) as a sign-function, as a rhetorical device, purely as a means to an end, in both versions.

There is a significant difference between the images to which I am referring and those images, like those in which a Japanese consular official appears, in which actors impersonate fictional spies. The latter are often clearly indicated because the people in them speak. In the still of “Mr Kita” below (item 4) even the two-shot composition indicates that it is fictional, displaying the contemporary style of a fiction film not the contemporary style of a documentary. The silent images of Asians, however, carry strong connotations of actuality footage; and because they are usually brief shots, silent and apparently taken in situ, they also appear to be “spy images”, images stolen from actuality without their subject’s full awareness. The spying spies have been spied upon: the film reproduces the activity it shows and condemns. That is, the complexity of these images is as much a matter of how they appear within both versions of the film as of the actual circumstances of their acquisition or the specific sense they are made to make.

It seems to me that this use of domestic Asian images in wartime adds a particularly nasty dimension to the long version’s demonisation of the Japanese which the authorised version cannot wholly erase. Ethnic prejudice has shaded into racial prejudice partly because the camera can make no ethnic distinction between Asian faces. Ford’s gesture in depositing the long version in the US archives means that we cannot, ought not, ignore either face of that racism: the appropriation of those images or the sense they are made to make in the long version. Ford’s visionary ability in the cinema was perfectly suited to fictions in which he argued for the value of that vision, but it made any attempt of his to match his vision to the world in which he and others actually lived both insensitive and tyrannical to say the the least. Wherever the two, vision and world, came into conflict, as they did in most of his documentaries and sometimes on the set, he showed himself to be brutal, cruel, ignorant and, most of all, deluded. The most notable exception to this may be Battle of Midway, a film in which the paranoia induced by the experience of war has one of its most calculated and effective expressions or, to put it in another way, a film in which delusion and ignorance are brutally and cruelly set out as a privileged account of war and warfare (thus a good fiction but a dubious account of reality).

2.

3.

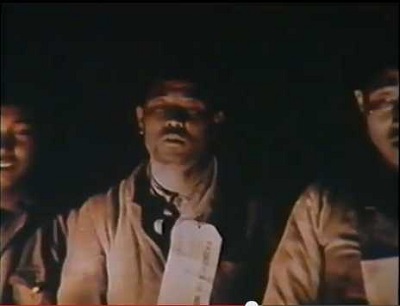

These images occur in both versions and in both version they are the first close up civilian reaction to the attack, presumably either staged or abducted from newsreel footage. The baby cries and points, immediately followed by a two shot of an older couple who stare impassively upwards. The woman turns her head to the left, looking at the man, then turns back to look upward again. These two heavily weighted, and somehow displaced if not misplaced, figural images recalled to me the student witness to gratuitous cruelty in Four Sons and the images of shawlies used to add mythic weight to Hangman’s House more than a decade before, as well as Lindsay Anderson’s remarks on Ford’s use of close-ups in Tobacco Road. They are followed by a single shot from newsreel footage of civilian reactions. Then . . .

4.

“One gentleman, when interviewed … ‘Mr. Kita'” (uncredited Asian actor, playing Nagao Kita, the Japanese Consul General). A recurring character in the long version, this is his first appearance in the authorised version and his last appearance in both versions. Interviewed by a white American reporter (Ralph Byrd), he says he doesn’t think it is an attack by Japan. There is a shot/reverse shot sequence of futile attempts to get him to admit that there is a Japanese attack, culminating in the official’s repeated “I have nothing to say” and his exit. In the long version this character is the director of Japanese domestic espionage operations in Hawaii. However the real Kita was probably not that – or at least that position has been claimed by Takeo Yoshikawa, who was arrested along with Kita shortly after the attack.

Something interesting is happening here. The three images that precede this one have been, momentarily perhaps, troubled. What is clearly marked in them – their “Asian-ness” – has been, might be, infused by a possibility, an opportunity, of “Japanese-ness” – the result of recognising that “Mr Kita’s” Asian-ness is “actually”, “really”, “Japanese-ness”. This invisible, incomplete, transformation, perhaps no transformation at all, prepares the ground for the transformation of the Japanese that will be accomplished later in the film.

Taken together, the four shots make up all the close shots of any civilians before and during the attack. Their placement and the sense they make in the short version may be interpreted as a retraction or partial withdrawal of the main argument of the long version, but the existence of the long version permits a cross-reading which complicates any easy interpretation, since each can be read as carrying with it vestiges of its reading invited by its original placement. Indeed one might say that in an author-centred reading of the authorised version, to which this writing appears to lend itself, a cross-reading of these images of Asian Hawaiian faces is mandated.

*

Although you know it is not my style, I do think that the “real history” of Japanese espionage in Hawaii, or what is accepted as “real history” these days, is relevant in this case. [13] The Japanese Consulate did include a person who was in charge of espionage in Hawaii. Indeed, Takeo Yoshikawa seems to have been in charge of German espionage as well (the chief German spy in Hawaii, Bernard Kuehn, was paid by Japan). He survived the war, although he was arrested shortly after the attack and then freed in an exchange of diplomats with Japan. Before he died he claimed that he personally did all the espionage and disinformation activities in Hawaii. He has also said that he got no help, no cooperation from Japanese-Americans (including nisei interned with him) because they were all stubbornly loyal to the United States.

His story stands in contrast to what is shown in the film, where a network of spies is apparently controlled by two men at the Consulate, and it conveniently exonerates Nagao Kita and the Japanese-Americans in Hawaii while at the same time building Yoshikawa’s image of as dedicated, self-sacrificing and heroic Japanese super spy. Only after I had learned about this man, did it strike me for the first time that there surely must have been some basis for what was said in the film about the spying which had been done in Hawaii – and only then did I begin to think about possible sources of such information and why the specifics of those activities might have been placed in this documentary film.

The film was made after those suspected of spying and disloyalty, including Consular officials and local Japanese-Americans, had been arrested and imprisoned. We are told in the film that these people were known to the authorities, which would seem to suggest that the principal Japanese means of gathering information and spreading disinformation were also known. On the other hand, it is not clear at all that the Americans knew about Yoshikawa specifically, and it does not seem likely that he would have volunteered any information even when interned in Arizona with Japanese-Americans who had been rounded up after the attack. Presumably those working on December 7th got their information about espionage from local police and/or the FBI, who believed that there was an effective local spy ring and that the Consulate only played a small part in its activities. After the attack and the neutralisation of the spy network, the extent of American knowledge of Japanese activities would become something to tell Japan about, in the same vein as “Mr. Tojo’s” boasts about what he thinks he knows about the state of the American navy after the attack. This, of course, could be done by means of a motion picture – and presumably would have been had the long version been released.

*

Close analysis 2: invisible faces in the short version

In contrast to the close-up, iconic Asian faces are seemingly innumerable invisible ones, scattered throughout the film. In the long version such faces act as background, Hawaiian scenery, signifying the ways things are in Hawaii for better or for worse, but in the short version, where we do not see crowds of Hawaii’s inhabitants until after the attack (that is, after the sequence of Asian faces just discussed), they take on a different tone. Here is a brief shot or two that occurs in both long and short versions.

Narration: “. . . together with hundreds of technicians, machinists, welders, mechanics, engineers – many of whom were recruited from the mainland – and working in complete harmony with Navy personnel”. This is an interesting juxtaposition of words and visuals, since the Asian faces would surely not have needed to have been recruited from the mainland. But we notice nothing unusual, relying on the narrator’s voice of truth as one does in documentaries from this period. This is a rather extreme instance of the invisibility of Asians who are actually, visibly, present in the film; for me it works in parallel with the absence of Asians in the roll call of Pearl Harbor’s dead.

These Asian faces appear in midshot or longshot, often surrounded in the shot by other faces or embedded within, and co-opted by, montage sequences intended to illustrate this or that phase of the attack’s aftermath. Many of the schoolchildren we see are Asian, connecting in the short version back directly only to the pointing baby (although in the long version also back to the spy cutting vegetation).

The Asian faces become “Japanese”, but not visible in the same way that the first four close-ups are visible, when the film’s attention is turned to the actions of the Japanese after the attack. In the long version these actions are introduced with the words, “Yes, all the people pitched in, the Japanese too”. (And Germans and Italians, no doubt). There follows a sequence on Japanese-American contributions to the war effort. Blood donors. War bonds. “Those who were known to be disloyal or undercover enemy agents were immediately taken into custody. Many [many what?] were forced out of business and interned. But, despite the wild Tokyo-inspired [“Tokyo-inspired” is good in the context of the long version] rumours and scuttlebutt, not one single solitary act of sabotage was committed on the 7th”.

Then, in both long and authorised versions: “Your bombs, Mr Tojo, brought many changes, and in no small measure served to complicate the already complex life of the Japanese in Hawaii.” (“Complex life” is pretty neat too). In this sequence the images are about signs and writing or, I should say, the effacement of Japanese culture in post-Pearl Harbor Hawaii. The Japanese we see are, then, shown in the process of becoming any-Asians-whatever – cinematically invisible – which seems as much a simplification as a complication when you come right down to it.

That is, what happens in the version that was authorised for public showing is that all Japanese-Hawaiian actions and contributions, both negative and positive, are downplayed whereas they are highlighted in the existing long version. The short version shows the Japanese, with the exception of “Japanese from Japan” as it were, as representative of the civilian Hawaiian populace, as targets, as victims, and finally not as Japanese at all, but Asian.

The last words of the short version are, again, “For all that take the sword shall perish with the sword”. But what of those who, like the figural and fictional Japanese in Hawaii portrayed in December 7th, do not “take the sword” but “also stand and wait”? How shall they perish? December 7th tells us. They shall be effaced.

The maternal

Young Mr Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath, Tobacco Road and How Green Was My Valley all contain strong figures of mothers and motherhood – extended and condensed into a few telling and remarkable lines spoken by Jane Darwell in The Battle of Midway. But in December 7th such figures are absent. Uncle Sam is seduced by young, beautiful women, but the film contains only fleeting, inconsequential images of women as carers and childbearers – maternal images in short.

The principal maternal role in the film is played by a man we have already seen, Captain [Homer N.] Wallin. He directs the salvage and repair of the ships damaged in the attack while characterising “Mr Tojo’s” propaganda as “scuttlebutt” [14] . He takes care of the wounded ships and makes them whole again.

The Chaplain officiating at the waterside mass is one of the few easily identifiable fictional characters who appears in more than one sequence (he is present, but not officiating at the memorial service). In both appearances he too is enacting a maternal (pastoral) role emphasising family and compassion. At the memorial service he stands in for America’s mothers, just as Jane Darwell’s voice does in The Battle of Midway.

It seems to me that strong figures of maternal women are fewer and fewer in Ford’s films after the war, and that maternal roles are taken over by male characters in those films. I am intrigued by the swiftness of the transition from feminine to masculine figures of maternity and by the way in which it is accomplished with neither fuss nor fanfare. “Let’s go home, Debbie” is often all it takes.

*

Honi soit qui mal y pense

1. Sex hygiene 1941? Contagious by touch.

2. An interior shot, coming after the label “USS ARIZONA” and just before an explosion, could have affected the young Kenneth Anger, who was 14 in 1941, the year he has claimed he made his first serious film. On the other hand it would have been surprising if Anger had not had a thing for sailors given the historical circumstances of his early adolescence. So, no: on balance, John Ford was probably not Kenneth Anger’s mother.

3. And there’s this. We (and the enemy) hear what they are talking about, but what has drawn them together?

Finally, scuttlebutt.

*

The thanks of a grateful nation

“Ford’s contributions to the war effort using his talent as a director and filmmaker demonstrate how anyone can aid in the security of a nation.” Central Intelligence Agency, “A Look Back . . . John Ford: War Movies”, 9 January 2009 (my emphasis).

*****

[1] December 7th: The Pearl Harbor Story (Kit Parker Films, 2011), which contains the surviving 82 minute version that Ford presumably deposited at the archive and a short “censored” version embedded within the longer version. The first section of the disc’s commentary for the longer version explicitly summarises Tag Gallagher’s argument, reproduced here, for thinking that the original version was altered and shortened in order to avoid issues raised by the wholesale incarceration of Japanese people on the US mainland. There are significant differences between this long version and the short version in the Ford At Fox set.

There is a great deal of additional material on the Kit Parker disc – two hours and four minutes if I have done the maths properly. This provides an extremely interesting context for understanding December 7th. It seems very clear that Ford’s unseen film had a direct influence on Frank Capra’s 1945 documentary, Know Your Enemy: Japan (included on the DVD), for example; and in footage from earlier newsreels and shorts one can trace some of the footage that appears in December 7th. There is also an excerpt from a Japanese television program about December 7th which finds the long version a very measured treatment.

[2] http://www.archive.org/details/gov.ntis.ava18528vnb1 Dept of War print c81:32 minutes; presumably the source of, or the same as, the print that Ford deposited at the archive. http://www.archive.org/details/gov.archives.arc.40099.bl OSS print 75:03 minutes. The long paragraph purporting to describe the film’s contents on the site linked above raises the suspicion that it may be significantly different from, as well as shorter than, the 81-82 minute version. However, this is not the case. There are some (inconsequential) sequences missing and a short section in which there is no soundtrack, but the film as a whole follows the structure of the longer iteration, both visually and aurally (that is, the description is incomplete). Perhaps what has survived represents a stage prior to a final cut (the last indefinite article in this sentence is quite deliberate).

[3] The text of this letter, undated, appears onscreen, but it is also quoted in Joseph McBride’s Searching for John Ford (University Press of Mississippi, 2011 [2001]), p. 354. (Subsequent references to this book appear as page numbers in the text.) I have avoided using McBride’s book until this point because I have wanted to avoid questions of historical scholarship in what is intended as a work of criticism. McBride’s is unquestionably the most authoritative biography of John Ford; and its account of the protracted making of December 7th and other matters has, I hope, allowed me to approach the work covered in this section of the review with freshened eyes.

[4] There is no credit title screen for either version of the film as presented on DVD, although credits have been superimposed by the DVD’s producers on the opening shots of the long version. Gallagher (all references, p. 573) credits Irving Pichel as Narrator and the December 7th DVD credits Carlton Young (perhaps Carleton Young?). The IMDb credits James Kevin McGuiness as “Narrator (voice) (as James K. McGuiness)” – and lists Pichel as “Narrator (voice) uncredited” but not Carlton or Carleton Young. The IMDb also credits George O’Brien as “Single Voice of the Dead Servicemen (voice)”, but that Single Voice sounds like Dana Andrews to me. Andrews is credited only as “Ghost of US sailor killed at Pearl Harbor” on the IMDb whereas the December 7th DVD identifies him, strangely, as “Lt. William R. Schick”. Gallagher (more reasonably?) lists Andrews as playing “Lt. William R. Schick” AND “dead sailor”. No source I have seen credits anyone with having played Uncle Sam’s secretary, the Chaplain/priest, the Japanese Consul General (“Mr Kita”), or the Japanese woman spy/rumour monger, all pretty big roles. (All credible sources agree that Gregg Toland and John Ford were “co-directors” of the film.) There is more on credits, at least indirectly, in the main text. However I do wonder where all the credit information comes from.

[5] I think it is quite likely that a long version of this film was at least close to completion in 1942, although I am not aware that there is any hard evidence for this one way or the other.

[6] I can’t resist remarking that Dana Andrews pronounces the Soviet leader’s name, “Stallion”.

[7] Parrish’s book, Hollywood Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (NY: Little Brown, 1988), appears to have been McBride’s source, but I have not seen a copy of that book. McBride’s citation and account appear on pp. 354-355.

[8] Parrish’s short account of the incident appears in his Growing Up in Hollywood (NY: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1976), on pp. 176-177. I suspect that Ford felt that the Body and Soul team were communists and that Parrish may have felt that pretty much everything Ford did for the short version of December 7th had actually been done by Parrish.

[9] McBride devotes the latter part of his chapter on Ford’s wartime activities to teasing out the relation between what happened to him in the war and the changes in his political stance in the years following the war, especially his developing anti-communism.

[10] Some 59 civilians are listed as having died during the attack. Apparently many of them may have been victims of unexploded US anti-aircraft shells. There are, as might be expected, many Japanese and Asian names on the list.

[11] There are many absences from the list of nations, presumably enemies and neutral nations, and some “rhetorical” manipulation of the names of those that are present: “England” and “Russia” for example. I wonder what Ford thought about Irish neutrality, a posture much reviled in Britain.

[12] See McBride, p. 386, fn 19. I do not think that Capra’s film was “even more xenophobic” than December 7th; one gets that impression only because Capra’s film is all about the Japanese and Ford’s only partly.

[13] The information about Takeo Yoshikawa in what follows comes from Will Deac’s article, “Taeko Yoshikawa: World War II Japanese Pearl Harbor Spy” (World War II, May 1997), reproduced at http://www.historynet.com/takeo-yoshikawa-world-war-ii-japanese-pearl-harbor-spy.htm

[14] I know you want to know what that word means – or, at least, I know that December 7th wants you to want to know what it means – so here are two definitions: (1) a barrel with a hole used to hold water for sailors to drink and thus, a shipboard drinking fountain or water cooler; (2) slang for gossip.

4.3 [My Darling Clementine (1946)]