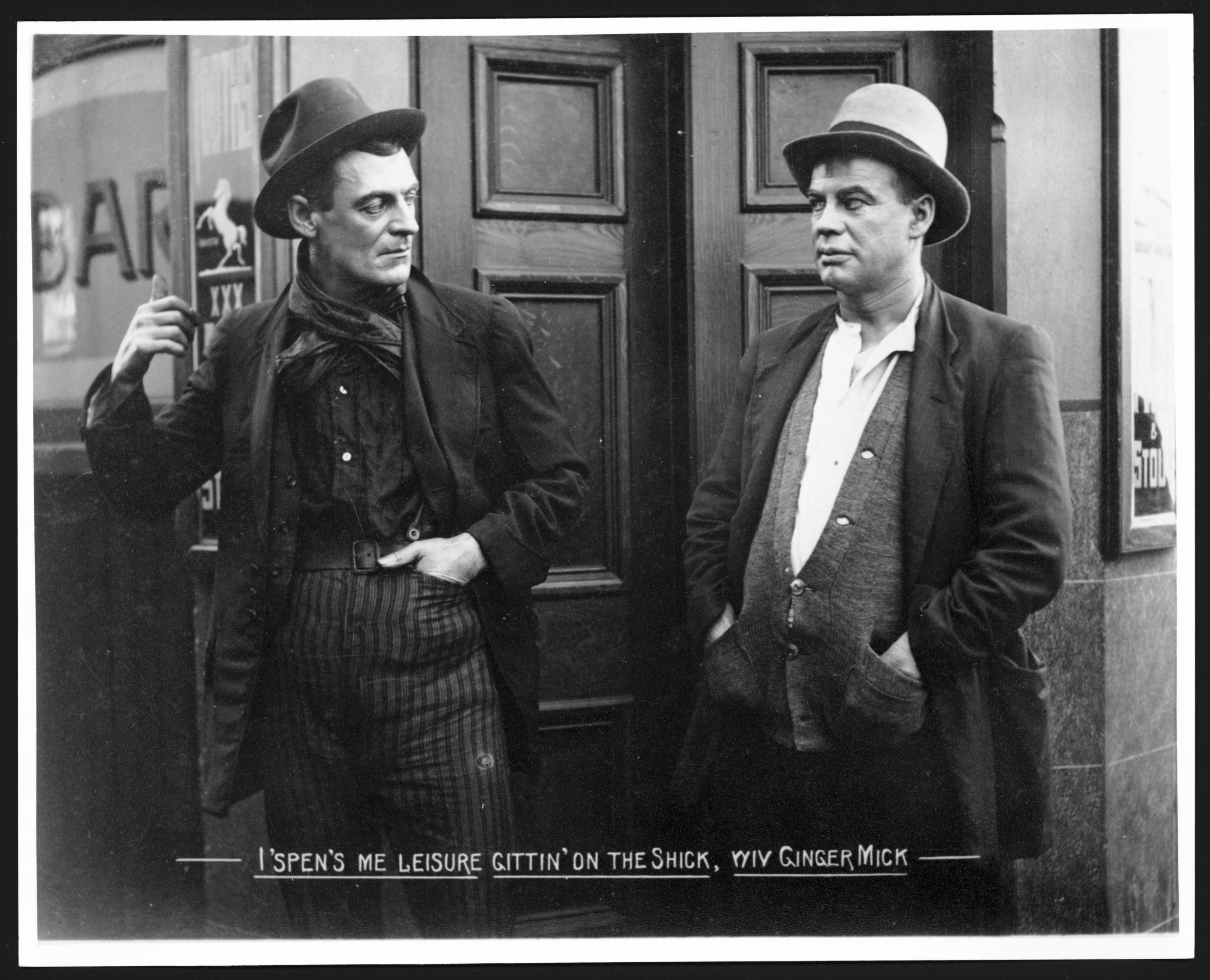

Ginger Mick (Gilbert Emery) and Bill (Arthur Tauchert) in Raymond Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke.

From the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Introduction

Raymond Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke, completed in 1919, is considered a landmark Australian film. Yet audiences in the United States did not feel as enthusiastic about the film as did those in Australia. In fact, the film was withdrawn from its planned US release after a series of unsuccessful test screenings. Several explanations have been put forward for the disparity in reception.[1] This paper takes up the argument made by Robert Dexter, the film’s publicist in Australia as well as the US, that American audiences were alienated by what they perceived as inadequate production values.[2] Dexter’s comments provide a clue that the different responses arose from a collision of two different aesthetic conventions – in fact, two different ways of understanding “production values”. While Australian reviewers praised the film’s “authentic” mise-en-scène, it seems that American audiences were drawn to the sheen and glitter of a completely different visual experience: the newly matured aesthetic of screen glamour.

This paper uses the costumes of Bill, the Sentimental Bloke (Arthur Tauchert) to reveal tensions between “authenticity” and artifice. Hats provide a particular focus, because as well as helping to draw Bill’s character, they contribute to the narrative. For instance, at moments when Bill struggles for words, he communicates by using his hat. He signals frustration or confusion by shoving his fedora to the back of his head, and when he is “properly” introduced to Doreen – after she has twice snubbed his approaches – his hat helps him overcome his awkwardness. “I dips me lid,” he tells us. “I sez, ‘Good Day.’ An’ bli-me, I ‘ad nothin’ more ter say!”

The social ease created by Bill’s hat thus provides the starting point of this exploration of male screen costuming, a topic that brings together considerations of fashion, gender roles, glamour, beauty, national identity, authenticity, and – underlying all of this -consumer culture.

What menswear can say

Everyday clothing, for all its banal familiarity, is a complex communication system. Honoré de Balzac, for instance, planned a “pathologie de la vie sociale”, of which his Traité de la Vie Elegante, published in 1830, was one section.[3] As Peter Brooks puts it, Balzac’s “vestignomonie” aimed to “establish the principles of legibility of the social animal, the sign-system by which every bodily adornment, movement, and gesture could be read”.[4]

More recently, Joanna Entwistle writes:

dress in everyday life … is an intimate aspect of the experience and presentation of the self and is so closely linked to identity that these three – dress, the body and the self – are not perceived separately but simultaneously.[5]

However, the late-eighteenth-century adoption of the three-piece suit in sombre colours has been labelled the “Great Masculine Renunciation”.[6] While the constraints of menswear can be “interesting” for a costume designer, suits provide only a “narrow spectrum” within which to work.[7] Menswear, many believe, reflects men’s “natural” restraint and “says” much less than female clothing about its wearer. Furthermore, in contrast to “logical” men, women – because they are “impulsive” and “emotional” – were seen as “natural” shoppers who were fanatical about fashion and self-display.[8] Brent Shannon counters this idea, arguing that “a more nuanced, rigourous examination of nineteenth-century middle-class male engagement with clothing and shopping” (598) reveals advertising between 1860 and 1914 that focused on men “broadened the range of acceptable masculinity” (599) and, moreover, consumer culture encouraged each man “to have a visual, physical, erotic self to be appraised by the public” (600). This suggests a robust and complicated visual environment in which men’s clothing, within its own muted symbolic system, conveyed information about the wearer’s personality, class, employment and income, and allegiance to social groups.

In 1918, when The Sentimental Bloke was made, menswear – including hats, “those great male emblems”[9] – contributed to changing ideas of masculinity. Thus Freud’s 1911 comment that “A hat is a symbol of a man (or of male genitals)”[10] does not do justice to the complexity of headgear, which can signal a range of cultural dimensions:

An event hidden in plain sight, the hat acts identity [sic.], combining signifier and signified as few objects do. The crown, helmet, habit, veil, yarmulke, turban reveal instant social status …[11]

Even far away from metropolitan centres of commerce and fashion, Australian males of the early twentieth century were aware of global trends in conventional headgear, and faced a plethora of choices when choosing their hats. In 1900, the London and American Store in Melbourne announced the arrival of a new shipment of Borsalino felt hats, imported from Italy, “a few of them in the new Slate Shade so fashionable in London at present”.[12] Five years later, Broken Hill gentlemen were invited to visit Reeks, Trenaman, and Co, for a Borsalino – “THE WORLD’S BEST” – and chose from “four different shapes and eight different shades”.[13]

Hat behaviour had its own social vocabulary, as described by this 1916 writer:

Young men enter the dress circle of a theatre wearing their boaters or their felts, take their seats beside their best girls, and remain thus covered during the performance … They like to exercise their freedom, to show their independence of polite custom, and their hats remain as if glued on their heads … So persistent is this dislike in the adoption of polite manners, that in the ordinary act of lifting the hat to a lady the act is of the clumsiest.[14]

Hats revealed even the strength of their wearers’ commitment to the nation. Senator James Guthrie (Victoria, National Party) in 1930 delivered a rousing speech about the necessity of buying Australian goods. “When leaving the luncheon room”, he complained, “I took up a hat that looked very like mine, but found that it … was a Borsalino … I took up nearly every hat in the room and found that most of them were either Stetsons, made in America, or Borsalinos, made in Italy.”[15]

Hats and film costuming

Given that clothing signifies so much in everyday life, it is not surprising that The Sentimental Bloke uses Bill’s headgear and clothing to indicate his progress from drunken lout to responsible husband and father. In part, the Bloke’s costumes infuse the film with cultural associations from the everyday world – as do any costumes. But once on the screen, their semiotic function is condensed, as the “authenticity” of everyday menswear combines with the “artifice” of filmmaking convention.

Silent film costume was not a highly developed language:

While the body was used in acting to express emotional complexities and to enunciate subtle gradations of feeling, costume was expected to simplify … it typified … [Without the actor’s voice] for audiences, attending to costume and gesture was somewhat like listening …[16]

That is, through the process of “typifying”, costume heightened already existing cultural signals, which audiences absorbed effortlessly, as if listening to ambient noise.

Furthermore, hats are connected to the most expressive parts of the body: “fingers, eyes and lips” are highest in the “hierarchy of vehicles of expression”.[17] Hats can hide or reveal the eyes, and focus attention on the face; they are, in fact, “the face’s ultimate theatrical device.”[18]

Certainly a female star’s hats performed complex functions, including displaying her face: “The film hat was the crucial accessory because it circled the libidinous face and framed that face’s other–worldly close-up. It staged those facial features, revealed character, and refracted light and dark.”[19]

Male stars’ hats are also important. The “essential sharp felt” hats of screen gangsters have been described as “the most consistent of the overdetermined accessories”.[20] Cowboys’ hats can denote “anti-hero status” (Marlon Brando’s sombrero in One-Eyed Jack [USA, 1960]), or historical accuracy (“Montana-Peak” hats in Lonesome Dove (television show, USA, 1990s).[21]

Hat 1: Battered, floppy and formless

The Bloke ambles into the film’s opening scenes wearing a pale-coloured soft-felt hat with a darker band. The hat has no particular shape or style. Its crown hasn’t been shaped; by comparison, the fedora worn by Ginger Mick (Gilbert Emery) has pinches in the front of the crown.

Bill’s companions at a two-up game nearly all wear felt hats, most of which are well shaped. Possibly the floppiness of Bill’s hat is a sign of poor quality materials, and thus of poverty: “The hat manufactured from wool is, of course, a lower grade, and has neither the appearance nor wearing capabilities of the fur article”, said Mr J Macfarlane, department store owner, in 1927.[22] Whatever the reason for Bill’s shapeless headgear, it suggests his own forlorn state, an impression amplified by his other garments. The edges of his cardigan are flaccid and uneven, his white shirt worn without its collar.

Unkempt when he goes into jail, Bill is still unkempt when he is released; when he hawks vegetables in the street; and when he first sees Doreen. (It is telling that, as Bill eyes Doreen at the market, his headgear looks particularly dirty, and a woman in the background energetically brushes a second-hand hat.) By the time of their “proper” introduction, however, the Bloke has smartened up. Although his hat is still quite formless, he wears a tie. A striped waistcoat, with a firm lower edge, replaces the cardigan with its over-stretched hem. Bill further polishes his appearance for his first date with Doreen. He again wears his striped vest, and has added a cravat.

Later still, the Bloke and Doreen watch a theatre production of Romeo and Juliet. His new job in a printing works explains his small bow tie. It is difficult to be completely sure, but it seems that he still wears his old hat. But whereas, on their first date, the crown of the hat sometimes seemed to have a pork-pie shape, now it resembles a bowler, and the brim is jauntily turned up all around.

National identity: affectionate “authenticity”

Early reviewers emphasised the “authenticity” of The Sentimental Bloke, an aspect of the film still much discussed.[23] Indeed, today’s writers are as intrigued and perplexed by the links between “realism” and nation as were those writing at the time of the film’s release. A Green Room writer predicted that the “Australian” nature of the film would ensure overseas commercial success:

The Sentimental Bloke is essentially Australian, but he belongs to the world at large, and his whims and fancies, his quaint philosophy and his altogether likeable personality, will be as readily welcomed in Britain and the United States as in the land of his creation.[24]

The film’s “natural”, “true to life” acting, reviewers said, surpassed Hollywood performances:

A noticeable feature of the acting is Doreen’s ability to keep her face true to the situation. You never catch a suspicion of a smile at the wrong moment, whereas a number of vaunted American screen-actresses are apt to lose control of the countenance under a temptation to smile where sadness or madness is required.[25]

This “naturalness” indicated the film was morally superior to Hollywood films:

it is a blessed relief and refreshment [sic.] after much of the twaddlesome posturing and camouflaged lechery we get in so many of the films that come to us from America … the story lives and has somewhat of the poetry of honest, inevitable workaday prose.[26]

Even before The Sentimental Bloke was released, reviewers at an early private screening praised the “wonderful realism” of Tauchert’s performance: “He might have been the actual ‘bloke’ who was born in the sordid slum areas …”[27] Gilbert Emery, playing Ginger Mick, was seen as similarly “authentic” with his “true Woolloomooloo slouch and manners perfect for push life”.[28] “Graceful” Doreen (Lottie Lyell) was “natural and life-like from beginning to end of the larrikin romance”[29] , wrote one reviewer, while another said: “Doreen … is impersonated with a naturalness and fitting charm that gives the real touch …”[30]

Location shooting in Sydney locations such as Woolloomooloo increased “realism”:

The incidents in the slums are depicted with vraisemblance which is most convincing. Many of the localities are easily recognised by those who know their whereabouts, so they are no mere cardboard and scrim fakes as is so often the case.[31]

Although Dennis’s verses were inspired by Melbourne’s larrikins, Sydney’s inner city areas – Paddington, Darlinghurst, Glebe, Newtown – had been notorious for larrikin behaviour.[32] Indeed, the director’s father, John W. Longford, had been Darlinghurst Goal’s Senior Warder and Recorder during the nineteenth century.[33] As a boy, Raymond Longford lived there and would have been keenly aware of the gangs.

The interiors – shot on open-roofed sets at Wonderland Amusement Park in Bondi – are complete artifice that conscientiously communicates the characters’ impoverished lives. The Bloke’s mean quarters, with its loud wallpaper, and even Mar’s Delft-filled sitting room, strongly resemble 1920s Sydney police photographs of crime scenes.[34] Cramped passageways, narrow sagging beds, mis-matched chairs, shelves with chipped paint, and even the way the furniture sits in the rooms: the film’s sets resemble the ghastly real-life interiors, illuminated by flashes from police cameras.

Similarly, police photographs show the crooks’ clothing styles are replicated in outfits worn in The Sentimental Bloke. And far from presenting newly purchased costumes or just-built sets – or a romantic idea of poverty – the film invites the audience to notice time’s effects on surfaces, in the build-up of grease, dirt, and sweat, the wear-and-tear of fabrics.

The Straw ’at Coot

After the play, Bill, Doreen and Ginger Mick visit a milkbar, a much more genteel milieu than the pubs in which we have seen Bill and Mick flirting with barmaids. The Straw ’at Coot, Bill’s rival, comes “dodgin’ round Doreen”. The Coot is only ever identified by his headgear, which somehow seems to sum up everything loathesome about him. But why is it so emblematic?

If nothing else, the straw hat sets the interloper apart. Although only one other minor character is seen briefly wearing similar headgear, it was popular for both men and women at the time. A style of hard-straw dress hat, its appearance around the end of the nineteenth century “marked the emergence of a new social informality and less rigid class structure.” [35] It was worn for casual summer activities such as picnics, seaside visits and – naturally – boating. Reekie describes the subtlety of its symbolic language:

Above all, a man’s boater represented masculinity. A lady’s straw sailor hat may have been almost identical in appearance except for the addition of a decorative ribbon. But those few inches of ribbon transformed a masculine hat into a clearly feminine one.[36]

The boater was acceptable wear among US middle and working classes[37] , so Bill’s disdain isn’t necessarily class-based. However, Sydney police photographs, mentioned earlier, show that crooks and larrikins from 1912 to 1948 avoided them, with almost all wearing well-brushed, well-shaped felt hats or, sometimes, cloth caps. Given its connection with leisure, working men may have believed that felt hats were a more sensible purchase because they could be worn for work as well as for leisure. The Straw ’at Coot, through his choice of headgear, may have been a walking insult to workingmen’s restricted choices, by signifying affluence (he had a hat just for leisure) as well as access to greater leisure time.

National identity: beauty and glamour

For Australians, the film’s “realism” affectionately celebrated Australia; for US audiences, the “realism” was, apparently, just ugly. The Sentimental Bloke was made far from Hollywood where the screen glamour became fully established during the early 1920s – so that, when the film was trialled in the United States in 1922, three years after the Australian premieres, it was seen in the context of an aesthetic that was reaching maximum impact.[38] Significantly, notions of beauty and glamour were entwined with American national pride, just as Australians saw the film’s unassuming “authenticity” as proudly representing their nation.

The US venture began after the film’s Australian success, when producers/distributors EJ and Dan Carroll investigated distribution through US distributor First National, headed by JD Williams.[39] According to Bob (Robert James) Dexter, Williams was enthusiastic about the film, and his previous years in Australia as an exhibitor meant “his sympathies were entirely Australian.”[40] Indeed, Longford claimed that Williams had provided the impetus behind the film by thrusting Dennis’s poems into Longford’s hands.[41]

At the time of the film’s US tests, Dexter, himself an Australian, was director of advertising and publicity for First National. He also had a previous connection with the film: before leaving for the US, he had handled the advertising for its Australian run.[42]

At the end of 1921, the film was screened in Los Angeles to an audience “entirely composed of Australia-born actors and actresses now playing in American photoplays”. These performers included Louise Lovely, Sylvia Bremer, and Enid Bennett.[43]

This was not, however, the first time The Sentimental Bloke had been seen in California. The Oakland Enquirer reported in December 1919 that “the first showing in this country of an Australian-made moving picture” took place at the St Francis Hotel. The reviewer, like the Australian and British critics, responded positively, declaring that the film:

is one of the most charming I have ever seen. The story is of homely heart-interest, clean as a whistle and brimming with appeal to all the better emotions. And how excellently the Australians cast the characters in their picture! The actors are of high excellence.[44]

The Oakland reviewer did, however, caution that Australian slang might be “too hard for a movie audience”:

If some of the slang in the captions to this truly superior picture are translated into American slang, and if this translation process is carried just far enough to make the captions easy of understanding without destroying the racy flavor … then The Sentimental Bloke will be a great success. [45]

The film’s US success did not eventuate, for reasons not entirely clear. Dexter explained that First National submitted the film to “six or ten public trials” as a condition of release:

We produced posters, press-material and accessories and announced The Sentimental Bloke on our schedule for the year, but in every public test the picture failed. That the public did not understand the slang cannot be offered as the reason … The Sentimental Bloke failed because of its inferior production qualities. From Australian standards it was a masterpiece; in comparison with American and Continental techniques it was hopelessly outclassed.[46]

Speaking of the dismal reception of Longford’s later CJ Dennis film The Dinkum Bloke (1923), Dexter said that his New York office staff asked him, “Is that really how Australians, dress, and live, and look?” He continued: “Nothing opened my eyes more to Australia’s film deficiencies”, adding:

Beauty is the merchandise of the motion picture, and Australia is practically barren of beauty. Nature made a wonderful job of this continent, but as human beings we are an ugly race … For screen purposes our features are all wrong.[47]

Although he was Australian, Dexter was immune to Longford’s visual representations of “typical”, “natural”, “authentic” Australians. Instead, he believed that Longford’s two films lacked beauty—the motion picture’s “merchandise”—and this lack undermined Australia’s international standing.

Nor was Dexter alone in connecting “beauty” with a sense of national pride (or shame). Enid Bennett, an Australian actress married to prominent Hollywood director Fred Niblo, played Maid Marion in Douglas Fairbanks’ 1923 Robin Hood and, in an interview publicising the film, supposedly said:

The strength of a nation has always been in the beauty of its women and civilization never would have been advanced so remarkably had there been no such beauty to wield such potential influence … Egypt, Greece and Rome, each, in turn, ruled the world and it was in these countries that physical pulchritude reached its highest standards of the times.[48]

Studios publicised beauty as a commodity they “owned”, from at least the mid-1910s[49] , but this focus intensified during the 1920s, with the development of the cohesive, studio-controlled design for the screen encompassing visual aspects from makeup to hair to set design. The glamour aesthetic, enshrining artifice as a virtue, was characterised by decadence, embellishment, luxury, and exotic references, especially to Oriental design.[50] Its exaggerated stylisations created a fantasy world that deliberately contrasted with “reality”. Merging “aristocratic, fashionable, sexual, theatrical, and consumerist appeals”, glamour created “the American motion picture’s signature style … [that] exercised an unprecedented influence over global aspirations, desires, and lifestyles”.[51] At the same time, the movie screen became a “shop window”[52] and, increasingly, “beauty” could be purchased from cosmetic surgeons.[53]

This encompassing, cohesive visual approach required that studio costume designers take over from ad hoc approaches in which stars provided their own screen clothes.[54] Costume departments, reflecting the studios’ centralised control of production, assumed responsibility for developing costumes that integrated with, and enhanced, the film’s narrative.

While seemingly frivolous, the phenomena of glamour and beauty can be seen as part of wider social transformations affecting both men and women. T J Jackson Lears identifies the early twentieth century as a period of “crucial moral change” which:

was the beginning of a shift from a Protestant ethos of salvation through self-denial toward a therapeutic ethos stressing self-realisation in this world—an ethos characterised by an almost obsessive concern with psychic and physical health …[55]

Plastic surgeon Dr Henry J Shierson, whose celebrity clients included Fanny Brice, reflected the interconnection of outer “self realisation” with inner, “therapeutic” health, in Variety in 1923: “The man or woman who has been made good to look upon through plastic surgery … has mental peace.”[56]

Cecil B DeMille defined his approach as “sex, sets and costumes”[57] , and, like other directors, used glamour’s glittering surfaces to explore sweeping post-War social changes. These productions “defined the limits of the moral revolution on the screen for the next decade”.[58] By 1922, when The Sentimental Bloke reached the US, DeMille had already made over ten features with extravagant production design and tantalising titles like Don’t Change Your Husband (USA, 1919) and Old Wives for New (USA, 1918).

It is easy to see, then, that the “natural” faces, clothes, sets and streets of The Sentimental Bloke held little appeal for audiences for whom glamour, beauty and consumerist inspiration were the hallmarks of a good film. “In view of the fact that 70 per cent of cinema audiences are women,” stated Bob Dexter, “and women’s interest lies primarily in the garments of the principals, extraordinary care must be taken if Australia desires to avoid the reputation of being a country of antiques.”

Ironically, though, the Bloke’s journey of “self realisation” aligns, to a great extent, with glamour’s endorsement of consumerism. Where, then, does his journey diverge from those shown in Hollywood films?

Hat 2: The brawler’s bowler

The Bloke and Doreen have a “ding dong row” over the attention Doreen receives from the Straw ’at Coot. Bill’s outfit, with new stiff white collar, displays his improved social standing, along with his involvement in consumer culture. Topping it all off is a new hat: a dark, hard-felt bowler that contrasts to the earlier formless soft-felt hat.

The bowler was worn informally when introduced in the 1860s. A favourite of working men, by the 1920s it nudged aside the top hat to become “correct day or business wear”, appropriate with an ensemble of black jacket/striped trousers or with the sort of dark lounge suit[59] worn by the Bloke.

Bill’s efforts to upgrade his clothes – and status – are, however, undermined by his unruliness towards the Straw ’at Coot, and then his belligerence towards Doreen. His behaviour has not kept pace with his appearance; there is dissonance between the clothes and the man.

As for the Bloke himself, Arthur Tauchert’s face and physique are those of the beefy “blue collar” brawler, a masculine type that was already superseded in Hollywood. A 1923 article reported:

The leading man of yesterday was a big six-footer, with a chest like a wrestler. He had wavy hair, a massive chin, and measured seventeen axe-handles across the back. But he’s out of date now. Enter the smaller, more refined type.[60]

One example of the older type was William Farnham, whose trademark was his on-screen fistfights.[61] By comparison, the Straw ’at Coot, sleek and slim, looks somewhat like the new type of leading man, best exemplified by Douglas Fairbanks. Fairbanks’ roles showcased his “playful physicality”[62] , and by the early 1920s, he had featured in expensive adventure films like The Mark of Zorro (Fred Niblo; 1920) and Robin Hood (Allan Dwan; 1922) – productions full of artifice and fantasy that contrasted strongly with the prosaic “authenticity” of The Sentimental Bloke.

Tea with Mar and the Yankee suit

Advertising targeted men as well as women with the same message. Everyone can buy commodities to construct a new, better identity: “If man was the victim of himself, the fruits of mass production were his saviour.”[63] Furthermore, by the end of the 1910s, achieving “success” was associated with the arts of “impression management”.[64]

Thus when Bill visits Mar for tea, he has obviously shopped for the occasion. His outfit is almost entirely “noo”, and his three-piece “Yankee suit”, garish tie, and two-tone shoes are hilariously excessive. The coat is long; it has multiple buttons on the pockets and flaps; the shirt collar too high and stiff; and the shoes too tight. The hat may be his faithful original, but it is brushed and shaped, and when he takes it off, his hair lies neatly combed across his balding forehead.

But what was a “Yankee suit” and why did Bill choose it for meeting Mar? The American-style suit had been in fashion since at least 1912, when George Davies Suits advertised “THE REAL AMERICAN SUIT!” in the Sydney Morning Herald:

I know I am kicking up plenty of noise about these American suits of mine—I can’t help it, I’m enthusiastic. So would you be, too, if you wear the American Suits, and saw the kind I make. They’re the real thing. Nifty, and just what you’re looking for.

SPECIAL CUTTER FROM AMERICA.[65]

In December that year, another Sydney establishment, Murdoch’s, urges “smart Xmas dressers” to consider buying a “Yankalian Suit” in “a particularly nobbly lot of fabrics for the festive season”:

These “Yankalian” suits embody

THE BROAD FULL SKIRT,

THE LONG LAPEL,

THE LOW-CUT VEST,

THE FULL TROUSERS

OF THE AMERICAN SUIT.[66]

In preparing to meet Mar, Bill may have consulted a sales assistant, just as he sought advice on “correct” behaviour from an etiquette book. Since the purpose of the visit was to gain Mar’s approval for his marriage to Doreen, it was important to get everything right. New clothes indicate disposable income; new American styling indicates an energetic, go-ahead type of personality; and the effort at presentability indicates a willingness to enter the middle-class world. But – comically – his clothes emulate those of the Straw ’at Coot, perhaps proving he was at least as worthy as his rival.

Through his efforts in “impression management”, however, Bill also successfully differentiates himself from the subcultural larrikin style exemplified by Ginger Mick. Mick folds his shiny scarf intricately around his neck, and his high-waisted pinstripe trousers express aggressive individualism. James Murray’s study of nineteenth-century larrikins notes their exaggerated costume of flared trousers worn with high-heeled, pointy boots. What really set apart larrikin dress, though, was “the way it was worn … the ‘leery’ look, the grin of studied and often maddening contempt, and the ability to spit through the teeth”[67] – all of which Ginger Mick demonstrates.

Hat 3: The working husband’s new fedora

Newly married, Bill gambles and drinks at Steeny Isaacs. During the misspent evening, the crown of his hat is dented, again reflecting the personal flaws of its owner. But, following forgiveness and redemption, Bill wears a light-coloured fedora – decorated with a prominent bow on its band – when he collects Uncle Jim at the railway station; Uncle Jim wears a very battered dark felt hat. And even though Uncle Jim remarks that he likes Bill’s “ugly mug”, Bill has a presentable middle-class look. It is no wonder, then, that Jim sees Bill as respectable and responsible – just the man to take over the farm.

Conclusion: The farmer’s functional hat

Bill’s rise in the world goes hand in hand with his growing literacy in clothes. Through his various jobs, he builds capital that he invests in commodities with which to re-make himself. He changes and adapts his hats – and also his collars, ties, vests, shirts, jackets and shirts – until he wins the girl and becomes a property owner. From the first formless hat onwards, his headgear displays his personality, taste, income, class aspirations, hopes and dreams, even the levels to which he pays attention to grooming. The hats also communicate the shame of his backsliding, and signal his understanding of, and compliance with, a more genteel, middle-class masculine identity.

While this coincides with the consumerist message of glamour – that people can, and should, improve themselves through shopping – the final scenes of the film undercut this position.

Bill, in the orchard, prunes branches while wearing working clothes. His hat, battered but functional, is almost comical, turning up at the front. Doreen joins him, carrying their baby, and they chat amongst the blossom. Next, we see Bill after work, on the verandah with Doreen and baby. Mirroring Uncle Jim’s habits, he smokes a pipe rather than cigarettes as he watches the sun set. He is content and prosperous-looking, hatless, and wearing a soft-collared white shirt and a soft cloth tie.

He neither slavishly follows Ginger Mick’s flash style, nor the “conspicuous” fashions of the Straw ’at Coot. After his long journey, he rejects both the larrikin subculture and fashion; he is a producer rather than simply a consumer. The source of his satisfaction is not membership of a clique, or stylish clothes, or even property ownership. Rather, the film makes clear that his satisfaction arises from a purposeful, productive life.

The hats in The Sentimental Bloke are, in conclusion, incessantly chatty. Not only do they “talk” for Bill when he is inarticulate; they “talk” about Bill, telling stories about his personality, frame of mind, class and income; and in these ways, they support the unfolding story. But most intriguingly, the hats also critique the narrative trajectory they have helped to create.

In one sense, then, the hats indicate that the production values of Longford’s film were high, since visual details like headgear were so carefully considered and so loaded with meaning. Far from simply reproducing documentary “reality”, there was, in fact, a high degree of artful arrangement behind the “authenticity.” But these production values are diametrically opposed to the kind of aesthetic ascendant in 1920s Hollywood, that delivered glittering, glamorous people, clothes and sets, and promoted stylised artifice. And certainly, any film that critiqued glamour and consumerism would find it hard to win the hearts and minds of 1920s American audiences.

[1] Some explanations are:

• the film’s lack of structure, compared to classical Hollywood cinema (David Boyd, “The Public and

Private Lives of a Sentimental Bloke”, Cinema Journal, 37, no. 4 (1998), 3-18);

• the film’s slang (Les A Murray, “The Sentimental Bloke”: Filming a Poem”, Metro Magazine, 74/75 (1987), 8-15;

• lack of sympathetic and committed promotion (Ina Bertrand and William D Routt, “The Big Bad Combine: Some Aspects of National Aspirations and International Constraints in the Australian Cinema, 1896-1929”, in The Australian Screen, eds. Albert Moran and Tom O’Regan (Ringwood, Vic.: Penguin, 1989).

[2] Commonwealth of Australia, Evidence Given to the Royal Commission into the Moving Picture Industry in Australia (Canberra, 1928). Robert James Dexter, Transcript: 873.

[3] Honoré de Balzac, Traité de la Vie Elegante (1830), rpt as Treatise on Elegant Living, trans Napoleon Jeffries (Wakefield Handbooks, Cambridge, MA, 2010).

[4] Peter Brooks, Body Work: Objects of Desire in Modern Narrative (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 83.

[5] Joanna Entwistle, The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2000), 10.

[6] The term originated in JC Flugel, The Psychology of Clothes (1930), London: Hogarth Press.

[7] Philippa Hawker, 2012, “The Very Model of a Savile Row Spy”, Sydney Morning Herald, January 23, p.9. The article discusses Jacqueline Durran’s costume designs for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (France/UK/Germany; 2011).

[8] Brent Shannon, “Refashioning Men: Fashion, Masculinity, and the Cultivation of the Male Consumer in Britain, 1860-1914”, Victorian Studies 46, no. 4 (2004): 598; Reekie, 61.

Reekie summarises studies of gender, shopping and department stores (up to 1993) in the Introduction to her Temptations: Sex, Selling and the Department Store: “Retailing and commerce were not beyond questions of sex and sexual difference, but constituted by them” (xiii).

[9] Anne Hollander, Sex and Suits: The Evolution of Modern Dress (New York: Kodansha International, 1994), 23.

[10] Sigmund Freud, quoted in Stella Bruzzi, Undressing Cinema: Clothing and Identity in the Movies (Routledge: London, 1997), 76.

[11] Drake Stutesman, “Storytelling: Marlene Dietrich’s Face and John Frederics’ Hats”, in Fashioning Film Stars: Dress, Culture, Identity, ed. Rachel Mosely (London: BFI Publishing, 2005), 30.

[12] Advertisement, Argus, 8 October 1900, 3.

[13] Advertisement, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 13 August 1906, 1.

[14] “Hats Off”, Mercury (Hobart), 20 November 1916, 3.

[15] “From the Capital”, Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton), 13 February 1930, 7.

Graham Shirley and Brian Adams note a tenuous link between Raymond Longford and Borsalino hats. Guiseppe Borsalino had financial interests in Italian feature films. To ensure distribution of the films in Australia, around 1912 he invested in the Fraser Film Release and Photographic Company. The Frasers between 1913 and 1915 distributed four of Longford’s films. Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, [Sydney, NSW]: Currency, 1989), 34.

[16] Jane Gaines, “Costume and Narrative: How Dress Tells the Woman’s Story”, in Fabrications: Costume and the Female Body, eds. Jane Gaines and Charlotte Herzog (New York: Routledge/AFI, 1990), 187-8.

[17] Gaines, 187-8.

[18] Stutesman, 30.

[19] Stutesman, 29-30.

[20] Bruzzi, 76.

[21] Jane Maria Gaines and Charlotte Cornelia Herzog, “The Fantasy of Authenticity in Western Costume”, in Back in the Saddle Again: New Essays on the Western, ed. Edward Buscombe and Roberta E Pearson (London: BFI Publishing, 1998), 174.

[22] “Australian Industries: Interesting Address”, Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton), 2 February 1927, 14. Macfarland was an owner of Rockhampton department store Messrs James Stewart and Co.).

[23] This paper deliberately focuses on perceptions at the time of the film’s release. In addition to Bertrand and Routt (1989), previously cited, more recent writers who engage with the “authenticity” of The Sentimental Bloke include:

• John Tulloch, Legends on the Screen: The Narrative Film in Australia, 1919-1929 (Sydney: Currency Press, 1981);

• Ina Bertrand, “The Sentimental Bloke: Realism and Romance”, in Film and the First World War, eds. Karel Dibbets & Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 1995);

• Susan Dermody, “Two Remakes: Ideologies of Film Production, 1919-1932”, in Nellie Melba, Ginger Meggs and Friends: Essays in Australian Cultural History, eds. Susan Dermody, John Docker & Drusilla Modjeska (Malmsbury, Vic.: Kibble Books, 1982);

• William D Routt, “Me Cobber, Ginger Mick: Stephano’s Story and Resistance to Empire in Early Australian Film,” in Twin Peaks: Australian and New Zealand Feature Films, ed. Deb Verhoeven (Melbourne: Damned Publishing, 1999).

Routt comments, “each writer has added new insight” to the discussion of authenticity and Australian-ness. He adds to the mix a non-Australian’s view that the film displays an “ordinariness” that is not particularly Australian.

[24] “Dennis’ Characters Step from His Famous Book”, Green Room, 1 November 1919.

[25] Bulletin, 16 October 1919.

[26] “The Sentimental Bloke”, Triad, 10 November 1919.

[27] “The Sentimental Bloke: Successful Private Screening of Film Version”, Advertiser (Adelaide), 27 November 1918.

[28] “Dennis’ Characters Step from His Famous Book”.

[29] “The Sentimental Bloke”, Sydney Morning Herald, 20 October 1919.

[30] Table Talk, 5 December 1918.

[31] Table Talk, 5 December 1918.

[32] James Murray, 1973, Larrikins: Nineteenth-Century Outrage (Melbourne: Lansdowne Press), 11.

[33] Murray, 180.

[34] Peter Doyle, Crooks like Us ([Sydney, NSW]: Foundation for the Historic Houses Trust, n.d.),

and Peter Doyle with Caleb Williams, City of Shadows: Sydney Police Photographs 1912-1948 (Sydney, NSW: Foundation for the Historic Houses Trust, 2005).

The images reproduced in these books have inspired two designer menswear collections, by American Ralph Lauren and Australian Jim Thompson (Georgina Safe, “Old Aussie Crims Model for Ralph Lauren”, Sydney Morning Herald, November 30 2011; Georgina Safe, “Criminally Minded”, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 2011).

[35] “History of Straw Hats and Felt Hats—Straw Dress Hats”, Hat History, 2006-2010, http://www.hathistory.org/dress/index.html (Accessed 20 December 2011).

[36] Reekie, 63.

[37] “History of Straw Hats and Felt Hats—Straw Dress Hats”.

[38] Routt (1999), and Bertrand and Routt (1989), point out, correctly, popular “lower-class” precursor films like the British My Old Dutch (Larry Trimble; 1915) and, from the US, Chimmie Fadden and Chimmie Fadden Out West (Cecil B DeMille, 1915), among others. Their success happened prior to the 1920s watershed for glamour-on-screen, after which their stories, characters, and design were less likely to attract aspirational audiences awash in consumer culture influences articulated through ever-increasing channels of influence.

[39] JD Williams (c.1877-1934) was an American who became an influential entrepreneur in Australian film exhibition. After returning to the US, he founded First National Exhibitors’ Circuit in 1917. See Jill Julius Matthews, Dance Hall and Picture Palace: Sydney’s Romance with Modernity (Strawberry Hills, NSW: Currency Press, 2005), especially 145-152.

[40] Commonwealth of Australia, 872.

[41] Raymond Longford, 1958, “Longford Typescript Memoir”, rpt in Raymond Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke: The Restored Version, monograph accompanying DVD release, National Film and Sound Archive, 2009, Canberra, ACT, pp.153-157.

[42] Commonwealth of Australia, 872.

[43] “How America Advertises It,” Picture Show, 1 January 1922, 40.

[44] “Australian Slang to Be Tried on the Movie Fans: A Slang Classic”, Oakland Enquirer, 20 December 1919.

[45] “Australian Slang to Be Tried on the Movie Fans”.

[46] Commonwealth of Australia, 872-873.

[47] Commonwealth of Australia, 873.

[48] “The Starry Way”, Photoplayer, 25 August 1923, 28.

[49] For example, in 1915, both Universal and the Reliance Motion Picture Corporation had sent “beauty trains” across the US, full of attractive young women who became a public display of each organisation’s “capital” (“Universal Beauty Train Begins its Tour”, Motion Picture News, 12 June 1915, 41; “‘June’ Winners Will Represent Ideal Womanhood”, Motion Picture News, 1 May 1915, 45).

[50] Maureen Turim, “Seduction and Elegance: The New Woman of Fashion in Silent Cinema”, in On Fashion, eds. Shari Benstock and Suzanne Ferris (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 140-158.

[51] Stephen Gundle, Glamour: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p.175.

[52] This connection was fostered by product tie-ins, a phenomenon discussed by Charles Eckert’s “The Carol Lombard in Macy’s Window”, reprinted in Fabrications: Costume and the Female Body, eds Jane Gaines and Charlotte Herzog (New York: Routledge, 1990), 100-121.

In part, this was not a new development. Live theatre preceded film as a showcase of consumer goods, particularly fashion. See Joel H Kaplan and Sheila Stowell, Theatre and Fashion: Oscar Wilde to the Suffragettes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), and Amanda G Taylor, “A Fashionable Production: Advertising and Consumer Culture on the Australian Stage”, Journal of Australian Studies 63 (2000), 119-128, 198-200.

[53] The relationship between Hollywood and plastic surgery started surprisingly early: in 1914, Mrs Syd Chaplin launched a malpractice suit for a nose job that went awry. Both men and women underwent procedures, and an impressive list of procedures were available by 1930: “nose corrections, new chins, pinned-back ears, face lifts, deep acid peels, fat removals …” (Photoplay Magazine, August, 58-59,102, accessed http://www.oldmagazinearticles.com/pdf/BEAUTY%20plastic.pdf, January 6, 2012).

[54] For an insight into how stars worked out what to wear, see “Dressing for the Movies”, Photoplay, January 1915, 117.

[55] TJ Jackson Lears, “From Salvation to Self-Realisation: Advertising and the Therapeutic Roots of the Consumer Culture, 1880-1930”, in The Culture of Consumption: Critical Essays in American History 1880-1980, eds. Richard Wightman Fox and TJ Jackson Lears (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983), 4.

[56] Henry J Shierson, “Plastic Surgery”, Variety, 23 August 1923, 14.

[57] Deborah Nadoolman Landis, 2007, Dressed: A Century of Hollywood Costume Design (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 6.

[58] Lary May, Screening out the Past (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 214.

[59] Penelope Byrde, The Male Image: Men’s Fashion in Britain 1300-1970 (London: BT Batsford, 1979), 185-6.

[60] Picture Show, 1 September 1923, 34.

[61] In 1919, the head of Fox’s scenario department said Farnum “has to have a scenario with a lot of rough and tumble fights, for that is one of the principal things the public goes to see. And he doesn’t wear evening clothes well” (Karl K. Kitchen, “Why Movie Scenarios Are What They Are”, Picture Show, 13 September 1919, 7)

[62] Gaylyn Studlar, This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 42.

[63] Stuart Ewen, Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976), 46.

[64] Lears, 8.

[65] Advertisement, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 1912, 5.

[66] Advertisement, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 December 1912, 3.

[67] Murray, 32-34.