Petulia (1968) sits at a crucial juncture in American/British director Richard Lester’s career. Some elements of its filigreed and somewhat hyperactive style relate it clearly to the often kinetic films that precede it – such as A Hard Day’s Night (1964), The Knack… and how to get it (1965), Help! (1965), and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966) – but the often innovative, integrated, substantive and novel use of these elements also suggests a series of other thematic and aesthetic possibilities and developments that Lester and his collaborators were only then beginning to explore (and only managed to return to intermittently afterwards). Although Petulia is rightly and routinely considered to be a “Richard Lester” movie, one in which he was characteristically involved at virtually all stages of production[1] ,it also has many affinities with the subsequent directorial work of its brilliant cinematographer, Nicolas Roeg (and Petulia was the last film in which he acted solely as Director of Photography)[2] . Nevertheless, it is Lester’s defining involvement in the film that has dominated most of the critical discussion since its release. Petulia is a film that is both in and out of time, a product of a particular moment in history and also somewhat detached from it. It provides a significant transition between classical narration, European art cinema and the emerging sensibility and spatio-temporal dynamics of New Hollywood.

Lester’s first American feature initially faced a relatively circumspect critical and popular response, but it has gained a significant reputation over the years. In some respects its status has outstripped that of Lester himself, whose often-claimed status as one of the most vibrant, refreshing and important auteurs of the 1960s barely outlasted the decade’s end. Nevertheless, in the following 40 years, and at various points in time since, a small group of critics have attempted to rethink Lester’s career, often coming to regard many of the more “mature” and circumscribed films he made in the 1970s – particularly The Three Musketeers (1973), but even films like Cuba (1979) and Superman II (1980) – as his greatest, most lasting and truly substantive contributions to the cinema. For example, Richard Corliss has argued for the superiority of the ’70s films and the less ambitious social and cultural projects they purvey: “Lester has proved as susceptible as any intelligent artist to the lure of the Grand Statement; but when he curbs his dogmatism and hires himself out [as he did in the 1970s], he can do handiwork as rich and satisfying as any in contemporary cinema” [3] . But most of these critics – including Lester’s greatest supporters, Neil Sinyard [4] and James Monaco[5] – have also made an exception of Petulia, a film that marks an important watershed in the director’s growing and more outwardly expressive emotional engagement with the cinema. Such an approach is, of course, hardly revelatory, as Lester himself has often singled out Petulia as the first of his films to feature fully rounded characters and a degree emotional depth: “Petulia is the only three-dimensional film that I’ve ever set out to make” [6] .

Although Petulia was somewhat ensconced by the end of the 1970s as one of the key American films of the previous decade and a half [7]

, including a significant turnaround from an initially ambivalent Andrew Sarris who had roundly dismissed Lester’s cinema in his seminal book American Cinema (arguing that his maddeningly fragmented work was “becoming increasingly irritating”)[8] , it is seemingly a film that still (and often) needs rediscovery. I think this is because it is a truly frank film that is difficult to pin down and compartmentalise, and also because, as I will discuss, it is a work both in and outside of the moment it outwardly purports to represent (San Francisco, 1967). This is, I think, almost the opposite of a film like Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967), which now seems badly dated and almost completely mired in its historical and cultural moment [9] . Petulia is, in essence, not a comfortable or easy film, taking as its “centre” a spluttering relationship between a world-weary surgeon, Archie (a somewhat sensitive and almost new-age George C. Scott), and a “kooky” – the film is based on John Haase’s 1966 novel, Me and the Arch Kook Petulia [10] – difficult to psychologically pin-down, neo-socialite Petulia (Julie Christie). As Richard Combs has suggestively argued, “The film itself twists and turns, seeking an outlet, seeking forms of expression, much as the characters do. Its despair escapes its subject, making Petulia itself a haunted film.” [11] Part of what I think Combs is trying to get at in his evocative and suggestively circular argument is the mercurial nature of Lester’s film, the ways in which its approach and view escape easy summarisation (or praise or dismissal).

Petulia refuses to see things in only one way, its fragmented and bifurcated structure and point-of-view a clear illustration and reinforcement of these qualities. As Lester has himself claimed: “I want to offer the scattershot of experience to an audience and make them work. I want to make each person sitting in a row see a different film.”[12] In this respect, Petulia marks an important development in Lester’s cinema, a shift away from the self-consciously Brechtian situations and comic book-like characters of many of his earlier (and often later) films. This is a development exemplified by the often-associational but hardly simple or one-dimensional asynchronous editing patterns that provide the film’s dazzling surface structure. Although Pauline Kael, in her famous essay “Trash, Art, and the Movies”[13] , was somewhat justified in criticising the more abject and straightforward of these associations and equivalences – say between domestic violence (a key theme) and the Vietnam War, ubiquitously playing on the film’s mostly silent and artfully framed television screens – she fails to recognise that these associations are actually more complex, varied, and self-consciously serialised than she distractedly observes. In fact, Kael is completely withering in her assessment of the film, stating that she had “rarely seen a more disagreeable, a more dislikeable (or bloodier) movie that Petulia” [14] , dismissing it – along with Stanley’s Kubrick’s equally Zeitgeist defining 2001: A Space Odyssey – as characteristic of the “obscenely self-important”[15] pretensions of what she considers the worst excesses of the “trashy” Hollywood art movie. In some ways Kael’s (not so) extraordinary outburst reveals more about her own prejudices, suspicions and disenfranchisement with the movies than it does about Lester’s film. These statements also revealingly suggest how much the film and Lester’s vision got under her skin. This is not to suggest that some of Kael’s criticisms haven’t “stuck” to the film, nor that they fail to exemplify and define a particular strand of still pertinent Lester criticism. But Kael’s patented brand of smash-and-grab film spectatorship, which rarely allowed for a film to work its way into her consciousness, or even raise the possibility of being revisited, was not in any way well-suited to Petulia’s slow-burn sensibility.

From a contemporary perspective, I think that Petulia is a film that has, in many ways, improved over time, particularly once its need to “stand in” for or comment on a particular time and place – San Francisco, 1967, the “hippie” movement, a shallow West Coast consumerism and a broader malaise – dissipated. This is a key reason as to why the film’s critical reputation never really coalesced until a decade or so after it release. In her general desire to celebrate the “good” trashy qualities of Hollywood mainstream cinema – and as a kind of flipside to the then dominant auteurist approaches of critics such as Sarris that celebrate the same films and even directors but on different terms – she abjectly fails to account for the tone, substance or even style of Petulia. Thus Kael zeros in on the film’s sharp but dizzying editing strategies as the most obvious symptom and demonstration of its shallow ideas and arguments – and it is true that the film’s withering viewpoint is a little “archer” than would seem necessary. But more complex and equivocal connections are also only part of the film’s overriding aesthetic.

Petulia also contains sequences of great and sustained power that are reliant on the fully engaged performances of its main actors, particularly Scott as Archie. A particularly strong example of this is the extended first scene between Archie and his recently divorced wife, Polo (Shirley Knight). Lester manages to give a sense of both what the couple once saw in each other and of the elements that ultimately tore their relationship to shreds, in this intense but deflating scene. This fraught sequence relies heavily on how each of the characters relate to the space and objects around them. It also uses these elements to frame the depleted nature of their relationship, despite the habitual and gestural bonds that still shade it: at various points the characters sink back into the physical and vocal mannerisms that would have once sustained their day-to-day interactions. The still simmering domestic tension between the couple finds an apt symbol in the tightly packed home-baked cookies that Polo brings as a peace offering and that Archie subsequently hurls at her back (in a wonderful conclusion we see Archie nibble some crumbs when Polo departs the scene). Although Petulia is often a slow-burn rather than a white-hot melodrama, this scene does foreground the theme of incipient, often domestic, violence that ranges across the film. This aspect finds its fullest articulation in the relationship between Petulia and her “too perfect”, almost plastic husband, David (Richard Chamberlain).

Despite announcing the centrality of Julie Christie’s eponymous but ultimately wearisome character in its title, Petulia is held together by Scott’s soulful, world-weary performance, as well as by the largely circumstantial but fine-grained descriptive detail it gives us of San Francisco, 1967. After research trips he took in 1966 and early 1967, Lester was, of course, well aware that he was filming during what was to become known as the “Summer of Love”. His view of this era or moment is more deflationary than celebratory, the end result providing a partial recognition that the true innovations and interest of the moment he was peripherally documenting were already passé (or had moved on) by the time of its popular discovery and the arrival of his film crew (though vibrant and vital pockets continued to flourish). Lester is himself very candid about the deficiencies of what he found:

By the time we came back to shoot in 1967, the sense of despair that I felt, the sense of depression and menace, was extraordinary. With all this flower power on the surface, the cynicism underneath was so strong […] In a year, the Haight-Ashbury scene had gone rotten. In our minds, it had become totally false, and the innocence was being used.[16]

Although the film tries to establish a somewhat flippant anti-Zeitgeist groove it still provides a fascinating, deflated but curiously vibrant document of the period. This is particularly revealing in relation to the release of the film, which although it documents the “era” of 1967 was actually released into the very different year of 1968: this difference was made painfully apparent to Lester and his producers when the film failed to screen at the abandoned Cannes Film Festival of that year. As a result, the film also has a sense of almost instant nostalgia (though it is in no way nostalgic in tone), both futuristic and eternally trapped in an impossible, inaccessible and now almost inconceivable moment. As I will discuss, this aspect is most apparent on the “edges” of the film, often in brief cameos, and in relation to the film’s often beautiful but sometimes-disjunctive soundtrack.

Ultimately, Petulia is a perplexing film that is tricky to look back on at a distance of over forty years. On the one hand, it seems like a prime example of the worst excesses of a temporally distressed, spatially convoluted and endlessly fashionable late ’60s countercultural American cinema. A symptom of a transitional cinema stranded between the forms, characters and values of old Hollywood, and the more spatially and temporally deconstructive tendencies of European cinema: influences which Lester had already absorbed in his previous work. In regard to this second influence, Petulia appears to be particularly indebted to such Alain Resnais films as Muriel ou le temps d’un retour (1963) and La guerre est finie (1966) – metaphysically and technically, if not politically. On the other, it is a soulful meditation upon a society’s loss of core values, purposes and representational systems, as well as a character’s clear sense of being in the world (or even in a film). At its core, this is one of those films where characters wander endlessly across familiar but ill-defined landscapes. In the process, an understanding of lost purpose and emptiness emerges from characters who have seemingly wandered in from a late ’30s romantic, at times virtually screwball comedy and are wondering what all the disappointment, disharmony and endlessly redefined sexual parameters are all about. This sense of the “rebooting” of an established and faded genre – so common in the decade to come – is reinforced by the actions of Petulia and the reactions of Archie, but the sensibility and romantic élan of 1930s Hollywood has well and truly departed the scene.

Perhaps one of the reasons for the film’s very mixed reception – championed by some, pilloried by others [17] – is because it has almost always been seen and critically regarded (both praised and condemned) as a “Richard Lester” film. This is a process and critical framework established and foregrounded in the film’s very formation and conception, as well as in its promotion. For example, a promotional film made to frame and somewhat conceptualise the film, Petulia: An Uncommon Movie (1968), relies heavily on statements that foreground the point-of view and approach of the director, and his “uncommon” approach to filmmaking. In this regard, the film is often too readily compared to such earlier, and less rounded, societal and group portraits as A Hard Day’s Night, The Knack… and how to get it and How I Won the War (1967). Lester’s own comments on Petulia, though still very much promoting it as an expression of his and his collaborators’ views of contemporary society, and the research they had undertaken, suggest that it should be regarded as a break from the director’s previous work, a cooler, “pristine”, but more soulful portrait of a culturally significant place and time at a key moment of transition. Even one of the director’s fiercest critics, David Thomson, who damningly claimed that “Lester’s example is a horrible warning” to other expatriate American filmmakers working in Europe, begrudgingly regarded Petulia as “his one American and most viewable movie”[18] . Although I intend to reconfirm and follow this auteurist approach to the film throughout the rest of this chapter, particularly within this essay, Petulia does suggest and encourages a series of other interpretative possibilities and approaches. It is a truly restless film, both in terms of its shifting surface and its broader social and cultural implications.

Petulia’s complex representation of place, space and time is, of course, one of its defining features. The most common view of the film is that it expresses something of the Zeitgeist of the late ’60s, its temporal, spatial and inter-personal fracturings characteristic of both post-nouvelle vague cinema and the very real shifts that were occurring in contemporary Western experience and perception. This is illustrated by the central relationship between Petulia and Archie, one that almost avoids physicality and moves immediately toward romantic (or something like it) obsession. In an ironic echo of the fragmented sex scenes in La guerre est finie, the film bypasses the direct representation of sex between Archie and Petulia and moves onto its interludes and aftermath. It elides this “revealing” moment of physical expression and instead shows both of them, in turn, sitting contemplatively in an adjacent room distractedly gazing at the other sleeping (or on far sides of the bed). This sequence, characteristically, splices and compartmentalises space, using editing and the dimensions of the frame to illustrate the full distance between the couple within Archie’s plaintively austere apartment. But as is also characteristic of the film in general, this sense of ennui and dislocation is tempered at various moments in the sequence, showing a warmer and more caring set of interactions that question the selective and highly elliptical moments that dominate the scene. This sequence also communicates and demonstrates the film’s precise command of cinematic temporality.

At times, the “content” of Petulia comes down to a rather clichéd and commonplace view of the malaise of contemporary society exemplified by mis-communication and the super-abundance of images, but more commonly it precisely and densely matches the film’s form. In fact, such a straightforward distinction between form and content is pretty much obliterated by the film. Lester has rightly and somewhat revealingly commented that part of the reason for the film’s deconstructive surface, its reliance on flashbacks, flashforwards, and other disorientating splinterings of image and sound, was the rather mundane and clichéd nature of the source material. In a fashion akin to Jean-Luc Godard, Lester has often been quick to state how much he disliked this source, using it as “template” to deface as much as adapt. Although Lester protests a little too much, it is in fact a perfectly serviceable novel that is nevertheless too driven by dialogue, the transformations wrought upon it reveal many of the key innovations (and some of the annoyances) that Lester, at his best, brought to the cinema. The two most obvious changes are in terms of locale – shifting from Los Angeles to San Francisco – and emphasis (essentially from the prosaic to the truly descriptive). Although Petulia contains often witty – for example, at one moment, in reply to Petulia’s premature claim, “I’m going to marry you, Archie”, Archie quips, “It’s the Pepsi generation” – revealing and sometimes quite wrenching dialogue, the details of mise en scène, the physical and psychological impact of objects and environments, and the gestural expressiveness of its characters are given much more emphasis. This contributes to the film’s layered sense of time and space. Although Lester claims he shifted locations due to the visual noisiness and dynamism he found in Los Angeles, his film is more attentive to and anchored by the specificities of place than the novel (which is very spare and almost non-descript in this regard).

Other key shifts between novel and film include the introduction of a more bifurcated point-of-view and a chronologically scrambled narrative structure, as well as the removal of tired and overly familiar framing sequences featuring Archie’s visits to his analyst. Although Lester claims he chose the non-chronological structure to help disguise the slightness of the film’s plot, it ultimately proves a perfect fit for the displaced and dissatisfied characters that lie at the story’s centre. Both emblematic of contemporary society and subject to its deficiencies, Archie and Petulia try hard to maintain a lightness of being that is both part of and alien to their natures. Lester is not that interested in imposing an environment or set of ideas on his characters in Petulia – a criticism that can be leveled at several of his other films – rather, he is concerned with that specific environment – or set of surroundings – and the characters who cannot be separated or distinguished from it. Although hardly as rigorous or metaphysical as the work of Terrence Malick in this respect, Lester’s concern for the “space around”[19] his characters has some interesting parallels with the cinema of Robert Altman. This concern for environment, the world and the character, is even true in relation to such “pre-ordained” personas as the Beatles featured in A Hard Day’s Night and Help!. At one level, the group seem to be somewhat distanced and “above” the mediated world they find themselves within. But they also emerge from this environment and are almost inconceivable outside of it. Petulia marks a maturation of style and outlook in this respect. Although Lester and his scriptwriters have stripped the novel of its expressed point-of-view – it is told, somewhat matter-of-factly through the perspective of Archie in the novel – this has not diminished the human qualities of the film, but rather spread them more equitably across it. It can be argued that none of the characters are very likeable, and all are infuriating and somewhat lost, but each has a complexity and weight that moves beyond the source.

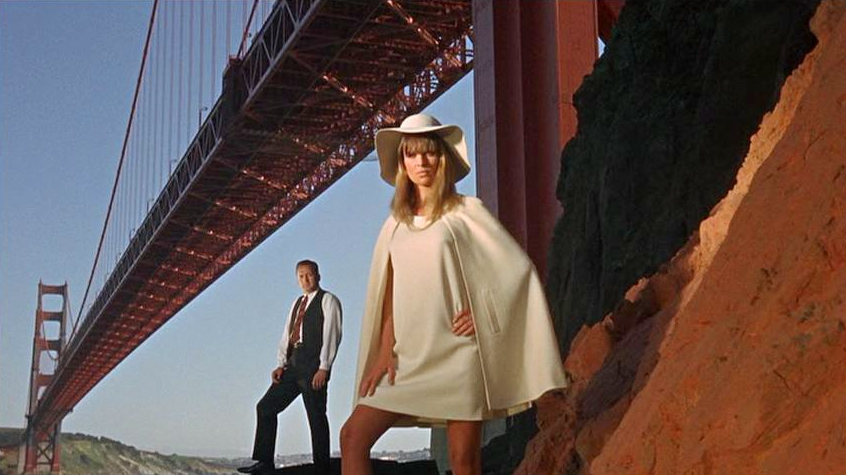

An interesting illustration of or supporting framework for these qualities is found in the film’s use of music. John Barry’s often-melancholy score at times seems to be channeling the more wistful elements of Bernard Hermann’s music for Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). In these moments the film reveals the extent to which its representation of the city of San Francisco is haunted and shaped (or at least marked) by earlier cinematic renderings. Petulia’s choice of locations also seems to both refer to these earlier, defining representations, and counters them by rendering the city as both eerily and materially familiar and somewhat non-descript, a modern or postmodern anywhere that just happens to be San Francisco (a quality that Don Siegel also plays with in Dirty Harry [1971], three years later). Whereas Hitchcock’s San Francisco is mesmerising in terms of its lonely and often depopulated streetscapes and municipal spaces – and in relation to the ways in which the characters drift hypnotically or drive silently through them – Lester’s is more vibrant, messy and (if this is possible in comparison to Vertigo) solipsistic. In the process, San Francisco emerges as something both familiar (all those end-of-the-’60s artefacts, the Muir Woods of Vertigo, etc.) and curiously, if commercially, surreal. This is best illustrated by the slightly vague sense of temporal disorientation (when and where are we?) and the carnivalesque that stretches across the film. These are, of course, some of the qualities that Kael most hated about Petulia, feeling that Lester failed to do justice to the beauty of San Francisco, her “home” town, while rubbing salt into the “wound” of contemporary America by “showing that even the best the country has to offer is rotten” [20] . Although Hitchcock’s film is truly transformative, taking the pictorial reality of San Francisco and subtly transforming it photographically[21] , I think it is inaccurate to take Kael’s lead and state that Petulia presents a straightforwardly negative view of contemporary American society and one of its “picture book” cities. The San Francisco presented here is often beautiful, and its quality of light not always so far removed from the foggy filters seductively imposed by Hitchcock, but Lester is concerned with creating and presenting a more circumstantial or encyclopedic view.

This aspect has also met with criticism. But one of the most impressive qualities of Lester’s work has always been his attention to detail – what Corliss calls his “penchant for the colloquial” [22] – his ability to use and see a particular point in time and place as both the place for fiction and of documentary. Amongst the most fascinating aspects of Petulia are those elements and observations that creep into the corners of the frame, or that arise because filming was taking place at a particular point in time. The film was actually shot during the “Summer of Love”, but this “aspect” often appears only on the edges of the film, just part-and-parcel of a fuller picture of San Francisco life that Petulia offers. Lester’s film is not overly concerned or preoccupied with this subculture and fixates more on the rarefied, and frankly conservative, world of the establishment and the professionally rich. Lester’s well-publicised filming style, using multiple cameras and often in actual locations that incorporate some passers-by, nevertheless opens up the possibility of producing a more rounded and incorporative societal portrait. But Lester’s take on late ’60s California moves away from the more self-conscious absences, spaces and explicit “time-outs” of Jacques Demy’s Model Shop (1969) and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970), “sympathetic outsider” films contemporaneous with Petulia that “document” a comparable late ’60s West Coast malaise. It is actually closer in tone and style – if not content – to John Boorman’s largely Los Angeles-set Point Blank (1967), a film that similarly shows a character outstripped and mystified by his or her modern physical surroundings and the abstract institutions of power that define them. Lester’s film shares several locations with Boorman’s more metaphysical tour-de-force (such as Alcatraz and Fort Mason next to the Golden Gate Bridge), but it communicates a much greater intimacy and nuanced sense of gesture (hardly something to be expected of Marvin’s brutal but incorruptible central character). In Petulia, the world is moving too quickly, is too distracted and contents itself too readily with the plastic pleasures of excessive automation, commodification and the gleaming tourist-perfect city. Amongst the “wonders” we see are a hospital that provides “dummy” television sets to encourage patients to want the real thing, an almost completely automated motel, and various synthesised and antiseptic interior environments. Whereas Antonioni and Demy’s outsider views become distracted by the visual field and curious subcultures that Zeitgeist California throws up, we only glimpse these on the periphery of Lester’s film. Perhaps the great achievement of Petulia is it’s representation of late ’60s San Francisco at arm’s length, creeping into the film at the end of shots, almost stumbled upon by Archie and Petulia as they disorientatingly navigate a series of almost vertiginously contradictory (from Nob Hill to Haight-Ashbury) terrains. The film is both soulful meditation and precise dissection.

The more varied tone and restless surface of Petulia is also reflected in the various themes and styles of Barry’s score. But it is equally revealed by the various nods the film makes towards the vibrant and burgeoning contemporary music scene of its day. As in A Hard Day’s Night, and to a lesser extent The Knack… or how to get it, Lester fortuitously found himself at a precipitous moment and place in contemporary pop culture. But whereas the earlier films are preoccupied with rendering that culture, commemorating it, or are at least enmeshed within it, Petulia shows how such a scene – now dominant in many superficial accounts of this era – can be somewhat peripheral, just part of the fabric of its idealised moment. Although Lester’s somewhat jaundiced view of the “Summer of Love” was informed by his own research and what he saw as the rapid commodification of the Haight-Ashbury phenomenon, the film is nevertheless fascinating in terms of what it documents. And, let’s be honest, a key attraction for many contemporary viewers of Petulia is precisely this aspect. If one was to provide a register of the various references the film makes to the counter-culture, the broadly hippie movement and the Bay Area music scene, it might seem that the film was preoccupied by these phenomena. For example, the film opens, somewhat anachronistically, with a series of crosscuts between various paraplegic car accident victims being taken through the back entrance of the Freemont Hotel and a performance by Big Brother and the Holding Company, fronted by Janis Joplin. The way the music cuts in and out in this sequence prepares the audience for the fragmentary, disorientating, mediated and circumspect journey they are about to take. We are shown a full-blooded performance by Big Brother placed within an event we are meant to regard somewhat sarcastically and ironically (aptly named the “Shake for Highway Safety”). We are some distance away here from the galvanising and playful musical numbers of A Hard Day’s Night here (though a little closer to Help!’s more distanced, insular and cynical performances and motives). Those who come to Petulia as a “youth” movie, expecting a record or treatise on the Bay Area counter-culture, will be disappointed. But I don’t think that this opening performance by Big Brother is meant to be regarded cynically, or as a cop-out, but actually points towards a more fully rounded representation of the “environment” that this movement emerged from.

Some of the other references to Haight-Ashbury and the hippie “movement” are more perfunctory and less successful. Although the ubiquitous posters and murals – including one of Jerry Garcia – effectively communicate the vibrancy of this movement and its ubiquitous place within the San Francisco of 1967, the film’s more direct references to various “hippie” characters – including a psychedelically painted “hippie” car that passes by asking for directions to a Chinese restaurant, a less than helpful pair of similarly coded characters that Archie encounters, various members of The Grateful Dead snidely voicing flippantly “hip” comments in one of the film’s worst scenes (where Petulia is taken unconscious from Archie’s apartment by an ambulance crew) – are considerably less charitable. Although these characters are no less positive than others found in the film, Lester deflates their importance and much-publicised idealism (particularly within a scene set in a 24-hour supermarket).

Petulia’s use of the defining band of this scene, The Grateful Dead, is equally equivocal. Although snatches of the seminal Grateful Dead song “Viola Lee Blues” are heard throughout [23] , along with frequently inserted images shot at one of the group’s concerts, they appear as just part of the milieu of the film, not a privileged element. Nevertheless, Lester was obviously aware of their significance, as he shows Archie somewhat anachronistically wandering into one of their performances in one of the most self-consciously psychedelic moments of the film. This is also one of the moments with the least motivation, as Archie seems very much out of place in such a sensorially rich environment (we see images of The Dead’s famous light shows and get some sense of why they – or their forebears, The Warlocks – were the favoured band at Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests).

Lester has often called himself an “anti-romantic” [24] . He has also routinely rejected more nostalgic approaches to the material he has formed into his various projects. Petulia is no exception to this patented anti-romanticism, but encounters this sensibility in a more direct fashion. Sarris has argued that the film essentially transplants the situations and characters of classical romantic comedy into contemporary society and cinema. It can indeed be argued that the main problems the central characters face is how to translate the romantic ideals of these forms into the messiness and realities of contemporary, affluent urban life. Lester’s anti-romanticism extends to the film’s somewhat bittersweet conclusion, an ending which marks another departure from Haase’s more optimistic, and bare-bones novel. In a move that is somewhat reminiscent of the coda of Eric Rohmer’s Ma nuit chez Maud (1969), Lester shifts the final action to a year or so later as Petulia is about to give birth in Archie’s hospital. Even at this late moment, the film suggests the possibility of Archie and Petulia running off together, abandoning the social and economic ties that have always stifled the chance of their escape (do they even really want to?). But even when the film seems about to be engulfed by Archie’s slowly turning romantic sensibility he loses his conviction, an (in)action which either illustrates his inability to act impulsively (in true ’30s screwball style) or underlines the out-modedness of such a set of romantic values, forms or even actions. This final deferral is either another cop-out or a weary acceptance of the true nature of things, as well as the shifting values and possibilities offered by both American cinema and society. The final unsettling moment, as Petulia plaintively calls Archie’s name as she is about to be anesthetised, is a moment of supreme ambivalence and uncertainty. Is she confirming her previous equivocal statement about her real feelings for Archie, or is this a final gesture towards the supreme ambivalence and uncertainty of Christie’s cipher-like character?

In this regard, Lester’s film almost seems like an anti-Vertigo. Although Hitchcock provides his own critique of romance, he does so within the obsessions and delusions of the form: James Stewart’s Scottie sees San Francisco as a perfect corollary for the timelessness, ethereality, emotional peaks and troughs (rendered in terms of the geographical highs and lows of the city), and necessary abstraction of such romantic ideals. When his characters visit the giant sequoias of Muir Woods (in Marin County) they are hypnotised and seduced by the “vertigo of time” that the ancient trees represent. In Petulia we are shown a cigarette commercial being filmed in the same place. Although the San Francisco of Lester’s film is still often beautiful, it is considerably less able to contain the romantic reveries and possibilities of its central couple. It has lost its sense of magic and transformation.

Molly Haskell has unsurprisingly attempted to reclaim Petulia as a “women’s film”, “the love film of the sixties” [25] as she calls it, and as a work that marks the key social, sexual and aesthetic ruptures of its era. As Haskell states, in their attempts to reclaim the ground of classical Hollywood romance “The older generation [in the film] has lost the capacity to live by pure feeling, while the new one lashes itself into a frenzy trying. And in the split, in the loss of connective tissue between man and woman, between one generation and another, they all lose the power to regenerate.” [26] This loss of an ability to “regenerate” applies to virtually all aspects of Petulia, including its place within the genres and forms of old Hollywood. Such a shift in emphasis marks a truly profound development in Lester’s cinema and helps provide one of the soul-searching landmarks of late 1960s American cinema.