Historical “understanding” is to be grasped, in principle, as the afterlife of that which is understood.(Walter Benjamin)[1]

The Exiles (Kent Mackenzie, 1961) is a film that virtually disappeared for fifty years. As a dramatic film about first nations people living in the city, it challenged the norms of both documentary and narrative filmmaking when it was originally released in 1961. Its “rediscovery” occurred in a compilation film about Los Angeles by Thom Andersen, who recognized the cultural value of a film that documented the coincident destinies of a city and a people, and made apparent uncanny parallels between latent colonialism and urban renewal in postwar America. The untimeliness of The Exiles, I want to argue here, is redeemed by a mode of film practice that is uniquely able to represent a non-linear history. Reading these two films, The Exiles and Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself (USA 2003), through the lens of Walter Benjamin’s radical historiography will demonstrate the potential of archival cinema to represent cultural history in new, untimely, ways.

The term “archival cinema” can refer to at least three different forms of cinema. In the first place, it can refer to found-footage and compilation film practices in which filmmakers mine the wealth of the archive to produce new work out of old. Secondly, it can refer to the restoration and recovery of films lost to the ravages of time and forgetfulness, a process that has been greatly enhanced by technologies that can produce new and cleaner restorations, as well as new modes of exhibition and distribution of film history. Thirdly, films on DVD are frequently packaged with their own “archive” of support materials, as one film often spawns a plethora of paratexts for the home viewer’s own archive. This essay will address all three of these practices in order to point out how Walter Benjamin’s theory of dialectical historiography is potentially realized in archival cinema.

Thom Andersen’s 2003 film Los Angeles Plays Itself is a compilation film that underscores the role of the essay film in the production of knowledge. Not all compilation films are essayistic, and not all essay films are based in archival footage, but these categories of compilation and archive frequently impinge on each other in the essay film, and when they do, they arguably provide a unique way of knowing about the world, mediated through cinema. Andersen’s essayistic narration is a critique of Hollywood and the ways that the film industry has appropriated Los Angeles for its various nefarious, fantastic and duplicitous ends; but it is also a melancholy ode to a city that has had to continually remake its own history in the face of its simulacral servitude to the dream factory. Los Angeles is a comparatively young city, burdened with its own lack of historicity. The deep irony of Los Angeles Plays Itself is that Andersen betrays his own obsessive cinephilia with his vast knowledge of film history, displayed in a brilliant montage of excerpts from genre cinema, auteur cinema, art cinema and independent cinema.

Amid the dozens of clips of Hollywood movies, Andersen lingers occasionally during the 169 minutes to offer more extended interpretations of a number of key titles, including Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1943), Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) and the television series Dragnet (1951 and 1967). Andersen’s commentary is full of insight and analysis. His montage is expertly paced, and the film offers a unique perspective on the relation of film to urban space in general, as well as the specific aspects of the L.A. setting. Los Angeles Plays Itself is far from comprehensive – especially since the focus is almost exclusively on the postwar city – and yet it is an excellent example of film criticism in the form of archival cinema. Moreover, it has had a direct impact on film history, in its recovery and redemption of The Exiles that had been more or less “lost” until Andersen “found” it and included it in his film.

Andersen returns to The Exiles three times in the course of his film, giving it as much attention as many much more well known titles. The Exiles had a limited film-festival run and some University screenings before being relegated to the University of Southern California archive, where it was occasionally shown in film classes by those in the know.[2] Set in Bunker Hill in downtown L.A., in a neighbourhood that was razed shortly after the film was shot, The Exiles is an anomalous cross between film noir and ethnography. Andersen introduces it as the movie that offers an antidote to Hollywood’s lies:

The best Bunker Hill movie is The Exiles, an independent low-budget film by Kent Mackenzie, about Indians from Arizona exiled in Los Angeles, shot in 1958, completed in 1962. It reveals the city as a place where reality is opaque, where different social orders coexist in the same space without touching each other. Better than any other movie, it proves that there once was a city here, before they tore it down and built a simulacrum.[3]

Towards the end of Los Angeles Plays Itself, Andersen describes “a city of walkers, a city of walking. It begins with The Exiles by Kent Mackenzie…” Excerpts of the film are followed by clips from films by Charles Burnett, Haile Gerima and Billy Woodbury, which Andersen classifies as “neorealist,” which for him “posits another kind of time, a spatialized, nonchronological time of meditation and memory.” Andersen’s mystification of the alterity of these disparate works may be somewhat simplistic and overblown, and yet his inclusion of The Exiles in Los Angeles Plays Itself launched a restoration of the film and a DVD release by Milestone, accompanied by its own “archive” of special features to contextualize the film. The restoration project, headed by Rob Lippman, produced a beautiful black-and-white print from the original 35mm negatives, with surprisingly high production values for an independent film.

Historical Dialectics

The conjunction of Los Angeles Plays Itself and The Exiles points to a new relation between cinema and its archival potential. With the proliferation of new digital technologies, the restoration, distribution, and exhibition of film history has entered a phase of re-invention and remaking. The Exiles has finally found an audience almost 50 years after being made, and it has done so through the cinephiliac mediation of archival cinema. Mackenzie’s film is a remarkable portrait of loss, redemption and cultural exile in which Native American cultural history is represented as a component of the modern city and cinematic representation. Moreover, its rediscovery serves as an excellent example of how historical discontinuity and its expression in untimely montage form can produce a dialectical image of history. The Exiles was “found” (or awakened) as part of a city-based compilation, taken apart and reassembled in pieces alongside films as diverse as Kiss Me Deadly (Robert Aldrich, 1955) and Omega Man (Boris Sagal, 1971).

The image archive has given us a film resource that the avant-garde has been mining for decades. In its earliest forms, Bruce Conner, Guy DeBord and Arthur Lipsett used the language of the found-footage fragment for a critique of image-based corporate culture.[4] In what Walter Benjamin described as the ongoing catastrophe of modernity, the film archive has become one of our most valuable resources for a language that can speak to the impasse of what he called historicism, or mystified forms of historiography. Archival film practices are now perhaps the emblematic art of the digital age and constitute the foundation of a new language of historical knowledge. In his note on “Excavation and Memory,” Walter Benjamin actually suggests that memory itself might be a medium.[5] It seems abundantly clear that we can point to the image-bank of contemporary media-saturated society as the realization of that medium, of which Benjamin glimpsed only the beginnings.

The practice of collecting, appropriating and reusing archival sounds and images remains an important technique of essayistic film practices. The archive and the archival have never been stable concepts, but inevitably shift with new technologies and new social formations. Not all uses are necessarily progressive, as the nationalistic popular documentary mode of Ken Burns, for example, demonstrates. In Benjamin’s own time of writing the Arcades Project, he assembled fragments of text that he “found” in the Bibliotheque Nationale as if they were images. Applying the surrealist mode of photomontage to the history of Parisian modernity, Benjamin was able to reconstruct the phantasmagoria of the emergent commodity culture of the 19th century city. When Benjamin declares that memory is a medium, he invokes a familiar archeological metaphor, suggesting that:

Genuine memory must yield an image of the person who remembers, in the same way a good archeological report not only informs us about the strata from which its findings originate, but also gives an account of the strata which first had to be broken through.[6]

The doubleness of Benjamin’s notion of memory clearly aligns it with modernism, and with psychoanalysis. Benjamin’s approach is echoed elsewhere, most notably by Derrida and Sven Spieker, who both argue, in somewhat different terms, that Freud at once undermined the archival principle and transformed it into a modernist medium. Benjamin’s larger body of work on the topic helps to further underscore how it was the cultural diffusion of film and photography, in conjunction with psychoanalytic discourse, that reformed, revised and reinvented the archive in the first decades of the twentieth century.

In Derrida’s reading of Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi’s reading of Freud’s reading of the Old Testament, Derrida argues that the archive after Freud is located at the breakdown of memory. As the threshold between inside and outside, the private and the public, the archival economy is predicated on a principle of loss. “Archive fever” is Derrida’s term for an archival desire that is closely bound to the infinite possibility of forgetting. If the archaic definition of the archival is one of consignation, of entrusting to a kind of house arrest, in its modern form, the practice of archiving has become unhoused and destabilized, precisely because memory, recollection and recall have themselves become challenges to the law of the institution. Derrida’s remarks on Freud’s attempt to write history have ramifications for the modern form of the archive more generally. He says:

The limits, the borders, and the distinctions have been shaken by an earthquake from which no classificational concept and no implementation of the archive can be sheltered. Order is no longer assured. [7]

Sven Spieker has very usefully fleshed out some of these theoretical ideas formulated by Benjamin, Derrida and Freud in terms of the avant-garde’s preoccupation with the archive manifest since the 1920s. He points out that the doubleness of the archive invokes a coextensive principle of order and chaos; that on the other side of the bureaucratic systems of classification that enable the instrumentality of the archive lies a productive disorder.[8] In fact, this is also what makes an archive so useful. Objects and documents are collected under one principle of classification, but they become legible according to other principles once they are removed from their original contexts and displaced into the archival setting.

The surrealist inquiry into the archive, which was also the impetus behind Benjamin’s archival method, involved an inversion of this principle. By collecting and archiving that which was previously unarchiveable – cultural trash aligned with the unconscious and preconscious – the archive becomes a medium of revelation. Spieker’s account foregrounds the spatial geography and temporal structure of the archive, noting how “in the modernist archive we encounter things we never expected to find; yet the archive is also the condition under which the unexpected, the sudden, the contingent can be sudden, unexpected and contingent.”[9] He also shows how the archival principle became linked to montage. The fragmentary and serial forms that objects and documents tend to take up once collected are co-extensive with the decentered gaze of modernist art practices.[10] Although he does not address archival film practices per se, Spieker provides a valuable framework for considering those practices within a larger cultural reconfiguration of the archive that took place over the course of the last century.

The claim that the use of “found footage” in the essay film constitutes a new form of knowledge contains an implicit revision of the critique of appropriation. The politics of appropriation have been typically associated with postmodern art practices and a co-extensive historical anxiety around work on “the signifier.” Where theorists such as Frederic Jameson saw appropriation as a kind of historical detachment, the practice has more recently been linked to the construction of cultural memory. Jan Verwoert, for example, describes the use of archival imagery as taking a distinctive turn with the shifts in global geo-politics that took place in the 1990s. The recourse to the archive is linked to “the re-emergence of a multiplicity of histories” that had hitherto been hidden within cold war ideologies. The ghosts of the past that return in the form of archival images speak to the many incomplete, unresolved, and latent histories of the 20th century. Verwoert also notes a shift in the critical discourse “away from a primary focus on the arbitrary and constructed character of the linguistic sign toward a desire to understand the performativity of language.”[11]

Thom Andersen’s narration in Los Angeles Plays Itself borrows some of the postmodern critique of image culture, but complicates it with a recognition of the untimeliness of historical disjunction and displacement. He points out that because L.A. is a city where there are few historical landmarks outside those that designate former movie locations, the reality of lived history in the city is overlaid with fictional representations of life in the city, including the full repertoire of car chases, explosions, thrillers, romances, teen pics and horror films. By organizing his cinematic collection around the use and reuse of specific L.A. locations, Andersen evokes a key principle of archival film practices. He says, “If we can appreciate documentaries for their dramatic qualities, perhaps we can appreciate fiction films for their documentary revelations.”[12] Extracting a sense of place from the multitude of films set in L.A., Andersen reveals cultural significance precisely by transforming Hollywood films into archival fragments.

Some of the highlights of Los Angeles Plays Itself are the sequences about specific buildings such as the Bradbury Building in downtown L.A., Frank Lloyd Wright’s Enni house, Union Station, Richard Neutra’s Lovell house, and other architectural sites in the city. The film’s documentary exegesis is accompanied by a sense of recognition and familiarity as the clips inevitably evoke the pleasures of American film history. Despite Andersen’s melancholic critique of the way the film industry has hijacked the city from its inhabitants, the film is lovingly constructed from the trivia and detritus of a cinephiliac collection. Los Angeles Plays Itself uses archival fragments of fiction films to reveal the documentary of Los Angeles that is concealed within Hollywood film history.

The indexicality of the imagery renders the films as traces of what Emma Cocker calls a “charged space of contestation and reinvention.”[13] Cocker’s position is that archival film practices develop what she calls “empathetic forms” of making meaning and cultural memory (9). Andersen’s film is a good example of this, and it furthermore exploits the doubleness of the archival film fragment once it is detached from the phantasmagoria. It becomes allegorical in Benjamin’s sense of the term, but it is far from dead. Each fragment retains some of the sensory aesthetics, formal properties and dynamic movement of Hollywood cinema, while situating these forms at the cusp of a lost city, a city that has always been disappearing behind its own preoccupation with representation.

Benjamin’s examination of the Paris arcades, which proceeds methodologically by assembling its various fragmentary documents, personalities, histories, views, representations and practices into archival form, is preoccupied with the analysis of the phantasmagoria. He takes this term to mean the conflation of display culture with commodity fetishism, invoking both Marx and Freud in his elaboration of the term. In his 1939 exposé, or introduction, to the Arcades Project, Benjamin quotes the dissident Blanqui as saying, “humanity will be prey to a mythic anguish so long as phantasmagoria occupies a place in it,”[14] and yet he also finds that a practice of appropriation is already part of the same social formation that produces the modern phantasmagoria. The collector is nominated as one of the unique figures in urban modernity who can divest things of their commodity character, by creating his own “phantasmagoria of the interior.”[15] In his conception of the collector, Benjamin struggles to recognize and reconfigure the utopian impulse within the modern phantasmagoria, and to rescue it from its deadening service to commodity capitalism.

One of the key concepts of The Arcades Project is that the “afterlife” of cultural phenomena is made possible by challenging conventions of historical progress and decline, or the grand narratives of history.[16] Benjamin’s historiography might, therefore, be considered as a theory of untimeliness. His own method was to allow the rags and refuse “to come into their own: by making use of them.” He furthermore thought of his practice as imagistic, working on “the historical index” of images that says “that they belong to a particular time; it says, above all, that they attain to legibility only at a particular time.” [17] Benjamin’s apparent mysticism may have confounded many of his critics, and his theory of dialectical images is open to many interpretations, and yet in light of the archival phantasmagoria of The Exiles, it can be extraordinarily convincing as a method of archival film historiography. From its curious history of apparent failure, followed by a virtual disappearance and subsequent rediscovery, it would seem that it is only as an archival film that The Exiles becomes legible.

The Exiles Revisited

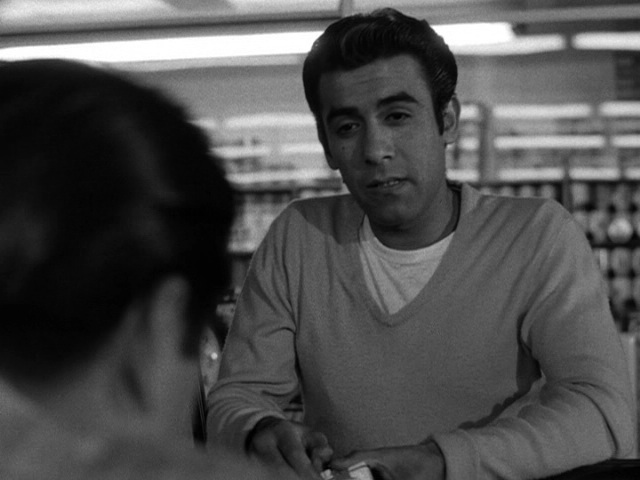

Mackenzie’s film was shot on 35mm, and one of its most striking features is the cinematography. The crew and the equipment were all borrowed from the industry, and they managed to translate their subjects – the Native Americans and their Bunker Hill location, into the expressive vocabulary of the Hollywood idiom, particularly film noir. The characters’ lives revolve around juke-boxes, fast cars, bryl-cream and girls in sweaters and New Look skirts. The film’s real accomplishment is to depict the lives of Native Americans as part of the popular culture of the 1950s. These people are exiles from the reservation, and their life in the city is certainly seen to be difficult. And yet, they are nevertheless depicted as being fully part of modernity, very much “of” their time, rather than being “outside of time” on the reservations with their parents.

Shots of the reservation include trailer homes and other paraphernalia of modern life, and yet these scenes are inserted as if they were flashbacks, provoked by letters from home and memories, creating the distinct sense of another temporality for those outside the city.

The novelty of The Exiles is commented on repeatedly by Sherman Alexie on the DVD audio track. He enthusiastically reports that this is the first time an Indian is seen wearing chinos in a movie. This is the first time we see an Indian getting gas in a movie, and so on. Whether this is true or not, his testimony confirms the central role of this film in American cultural history. The modernity of everyday life in the city also marks the end of other more traditional modes of life, and the film is far from a celebration. The climactic scene of a nighttime drumming circle in the Hollywood hills with all the paraphernalia of rockabilly delinquency is a remarkable scene of urban ritual, even while the women are clearly left on the sidelines, and the film does not shy away from a critique of gender roles. In fact, one of the three characters whose voice-overs narrate the film is that of Yvonne, and her gendered subjectivity points to another way in which the film is ahead of its time.

Among the many supplements on the Milestone DVD of The Exiles is Kent Mackenzie’s MA thesis on the making of the film, deposited at University of Southern California in 1964. This is a fascinating and well-written document that not only illuminates the filmmaker’s objectives and methods, but also constitutes another dimension of the archival scope of the digital archive. Mackenzie, who died in 1980, made a student film about Bunker Hill in 1956 in which he featured some elderly residents who speak in voice-over about their “village” in the middle of the city that was on the verge of being demolished. The technique of featuring non-professional actors in their everyday setting, with their thoughts and feelings in voice-over is the basic strategy of The Exiles and Bunker Hill, both of which were shot with non-synch equipment. The DVD package includes Bunker Hill along with three other of Mackenzie’s short films from the 60s, and two additional documentaries on Bunker Hill, clips from Los Angeles Plays Itself, two audio interviews with Sherman Alexie and others, and a collection of documents under the rubric, “The Mackenzie Files.” The auteurist bent is counter-balanced by an acknowledgement of the collective filmmaking approach articulated in Mackenzie’s thesis, and in an audio recording of a 2008 panel that includes several of his collaborators.

Mackenzie’s 1956 film does not note the presence of Indians in Bunker Hill, but a short film by Greg Kimble in the Milestone package does.[18] Laurié, an art director who worked with Renoir and Chaplin, shot some beautiful “everyday” footage in the 1940s, although he never apparently edited or released it in documentary form. His focus is primarily the decaying Victorian architecture, but he also shows what appear to be Indian children playing in the alleys and yards of the “neighbourhood in decline.” The casual, poetic feel of his footage recalls Flaherty, and Kimble’s narration tends toward the poetic, glossing over the evident litter, disrepair, blatant poverty and urban decay that have clearly already affected the area. This footage makes an interesting comparison with both of Mackenzie’s Bunker Hill films, which tend to sidestep signs of poverty in order to focus more strongly on the communities in residence.

Bunker Hill was developed in the mid-1880s with huge, sprawling, Victorian mansions overlooking the city. The Angel’s Flight funicular was established in 1901, and the conversion of mansions to rooming houses started as early as the 1920s. Cheap hotels and apartment buildings were squeezed in between the old houses, creating a labyrinth of densely populated, narrow streets, darkened by the Angel’s Flight overpass and the deep shadows of tall buildings on a steep incline. Not surprisingly, the neighbourhood became a choice location for film noir. As Andersen says, “by the 1950s it had become a neighbourhood of rooming houses where a man who knew too much might hole up or hide out.” Following clips of Shockproof (Sam Fuller, 1949), The Unfaithful (Vincent Sherman, 1947) and Kiss Me Deadly, he cuts to The Exiles as, “The best Bunker Hill film,” privileging it over the Hollywood treatments. And yet the remarkable thing about The Exiles is just how Hollywood it is. Unlike Laurié’s footage, Mackenzie’s is scripted, staged, lit and post-synched. Mackenzie claims to have been influenced by Flaherty and Humphrey Jennings, and yet his aesthetics in this film are much closer to that of Aldrich and Kiss Me Deadly. He shows no Indians passed out on back porches as Laurié does, but instead shows them going to movies, drinking in bars, driving fast cars and horsing around having fun.

Inspired by an article in Harpers, Mackenzie wanted to make a “truthful” film about Indians displaced from the reservation. He came to know the younger generation living in Bunker Hill by meeting them in the bars along Main Street and Broadway. He wanted to make a film that would, on the one hand, show the inner emotions of the men and women, and on the other, avoid all the pitfalls of dramatic commercial cinema, which he found to be far removed from real life. His training at USC, however, had only prepared him for the film techniques used by the industry, and all of his crew were also USC recent graduates with very limited experience but access to sophisticated 35mm equipment. He speaks of his team in the first person plural (“we”) and they were all committed to re-inventing cinema along the lines of Flaherty and the neorealists as a kind of collective intervention. The Exiles took three years to make, from 1958 to 1961, and had an extraordinarily difficult production history, due to limited financing, experimental methods and general inexperience. Mackenzie readily admits that his ambition far outstripped his financial means and his technical abilities.

The film challenged audiences’ perception of Indians by situating them in an urban environment. To help orient audiences, the filmmakers added a prologue of conventional, familiar, imagery of the romanticized Indian photographed by Edward S. Curtis, with a voice-over explaining the history of the reservation system and the postwar exodus of young people.[19] However, critics of the time did not take kindly to the depiction of drunken Indians, and the film was deemed “too negative” at the prestigious Flaherty Seminar in Puerto Rico in 1961.[20] Mackenzie’s elaborate attempt to portray Indians as urban citizens with urban experiences and challenges was appreciated only at European film festivals – Venice and Manneheim – where the film was very well received. Mackenzie understood himself as part of a new “movement” of realistic film practices that included Kurosawa and Cassavetes, even if his own experiment he deemed to be a failure. American audiences and critics did not seem to recognize “Indians” without the “untimely” conventions of colonial romanticism. They were perhaps more comfortable seeing native peoples in rural settings cut off from modernity, and prejudices against Indians “misbehaving” in the city prevented Americans from appreciating the kind of characters that are developed in The Exiles. European audiences seemed more ready to accept the characters as cinematic “others,” or as Americans first and Indians second.

Despite Mackenzie’s own negative assessment, and the film’s 47-year disappearance, the re-release, which is “presented” by Sherman Alexie and Charles Burnett, has been endorsed by contemporary critics of independent, alternative cinema. It was included in lists of the best films of the year in both Film Quarterly and Film Comment in 2008 when it was theatrically released,[21] and it received rave reviews, although no extended analyses, in Cineaste, Cahiers du Cinema, Sight and Sound, Filmmaker, Cinema Scope, and The New Yorker.[22] The restoration itself accounts for some of the praise, as the new print has the rare glitter and glow of a freshly minted black-and-white gem from the period. Several critics declare the film to be a neglected masterpiece of the American Independent cinema, and Richard Brody in the New Yorker goes so far as to say that it displays “epic grandeur” and “monumental intimacy.” Brody concludes his brief endorsement with: “Few directors in the history of cinema have so skillfully and deeply joined a sense of place with the subtle flux of inner life.”[23]

Not surprisingly, the best commentary on the film upon its belated re-release is Thom Andersen’s contribution to Film Comment. He points out how The Exiles’ loosely-wrought narrative of a night-in-the-life of a group of friends creates an unusual sense of temporality.[24] They pass the time by drinking, dreaming, and going to the movies. One of the characters, Tommy, says in his voice-over monologue that he doesn’t mind doing jail time. Time is time: “it’s just time to me.” It is precisely this existential sense of being that lifts the film out of its alcoholic haze and renders the characters as fully modern. He comes close to being a Baudelairean literary character, acutely aware of the existential duration of everyday life, not unlike the writer-hero of John Fante’s Ask the Dust, set in Bunker Hill in the 1930s. Andersen points out that this sense of time is especially intense in light of the “dreamtime” of a flashback (which is not a flashback at all) to the reservation on the one hand, and the imminent demise and total eradication of the Bunker Hill neighbourhood on the other. And yet, the latter event is never actually addressed in The Exiles. Unlike Mackenzie’s Bunker Hill, made five years earlier, the anticipated demolition and displacement is only extra-textual knowledge. The Indians themselves live without a future.

The single “flashback” occurs as Homer, one of the three main characters, reads a letter from home while his buddy buys some wine in a liquor store. In front of the window display of bottles and signs, Homer is alone on the night-lit street. Dissolve to shots of a rural scene with a man chanting, children playing, women lounging under a shady tree, and a mountain-ridge landscape framing the compound. Unlike the montage of Curtis photos with which the film opens, it is clearly set in the present-tense of 1950s America. You can tell by the trailer home that the “flashback” is not necessarily set in the past, but in a parallel universe of the present. The characters back home speak in both English and an un-subtitled Indian language that underscores their cultural remoteness from the city. While the Curtis photos set up a contrast of representational strategies, the flashback sets up a spatial contrast in which the coevalness of rural and urban temporalities is given vivid expression. One of the effects of this contrast is to emphasize the glamour and energy of the city in relation to the banality of the “everyday” in the countryside. As the title of the film stresses, the residents of Bunker Hill are in exile from that other place that seems distant both in space and in time, but which is still very much part of who they are.

The Exiles’ accomplishment is precisely its depiction of the expressive phantasmagoria of “everyday” in the city at night. Mackenzie and his cinematographers, Erik Daarstad, Robert Kaufman and John Morrill, were all trained at USC to shoot and edit according to the Hollywood model. Against all odds, they managed to light the scenes and shoot them with truck-loads of equipment and elaborate set-ups. Even if they were aiming to recreate a “natural” feel, the result is that of movie lighting with shadows and depth, and because it is mainly at night, the source-lights of neon signs, shop windows, and car lights give the film its distinctive noir feel. Many of the daylight shots have a softness to them, perhaps because they were shot in the early morning hours. The whole film is bathed in a kind of glow of the city which gives the film its transcendent quality.

Mackenzie also edited his footage according to conventions of continuity editing, so despite the challenges of working with nonprofessionals on location, the film has a remarkable fluidity. Once one reads Mackenzie’s account of the production, which was largely fueled on alcohol, and involved a lot of misplaced extras and A.W.O.L. actors, this is especially remarkable. Members of the cast periodically disappeared to do jail time, and members of the crew were drafted and shipped off to Korea for periods of time. The rhythm of the film is partially accomplished through the use of pauses and transitions that include emblematic shots of the city and shots of passers-by and extras. Dissolves are used for these interruptions and for many of the transitions, while action scenes are cut with quick close and medium shots. The voice-overs of the three main characters are used over some of the transitions, and some of the dialogue scenes in which the on-screen dialogue is silenced. The post-synched dialogue is at times stilted, but it is mainly characters egging each other on, “Come on, man,” being the most repeated phrase in the film. The dialogue functions on the same level as the juke-box music and the lighting: to create atmosphere.

The irony of The Exiles is that despite the filmmakers’ eagerness to get away from the norms of commercial cinema, they actually used those techniques to give expression to the unusual subject-matter. The non-professional Indian actors, who re-enact stories and scenes from their own lives, contributed a great deal to the script, but their monologues are nevertheless carefully shaped in order to create characters with minimal means. Homer is a tough guy who spends the evening in bars, playing poker and picking fights. His pregnant wife, Yvonne, longs to raise her child in the city and improve her standard of living. She gazes into shop windows and talks about how she has stopped praying and going to church because her prayers have never been answered. Tommy, on the other hand, is a party boy with the graceful moves of a James Dean or a rocker of the period. He picks up a girl in bar and takes her up to Hill X where the community gathers for Indian drumming and dancing at the end of the film.

The gathering on Hill X gives the film a sense of dramatic closure, ending with a small group straggling home the next morning. The partying is a celebration of Indigenous roots and also an opportunity to drink all night. In the aftermath of colonization, cultural rituals are combined in complicated ways. As Andersen puts it, the “Indians’” attempt to reclaim ancestral rites is somewhat pathetic: “Their efforts to revive the old ceremonies and solidarities breaks up into almost desultory sexual assaults and fights.”[25] Tommy is rebuffed by his girl, who crawls into the backseat of a car with a blanket around her.

The Exiles is remarkably acute about gender roles and inequities in this displaced community. Yvonne remarks that she would like to go out with Homer and the boys, but he doesn’t want her around. So, after she cooks a meal for them, the men drop her off at the movies before heading out to carouse. The movie marquee says The Iron Sherriff – a Western, ironically, starring Sterling Hayden. She ends up spending the night at a girlfriend’s home where they talk about her pregnancy and look at old photos. Yvonne’s longing for domesticity is the film’s gesture toward pathos; although she also seems torn, longing equally for the fast life when she gazes down at her husband and friends returning at dawn to Bunker Hill.

In one of the film’s most remarkable scenes, Tommy, Cliff, and two girls, Clydean and Mary, pull into a gas station in Cliff’s Oldsmobile convertible following a dynamic scene of them laughing, drinking and driving through the 3rd street tunnel. As Tommy, Cliff, and Clydean wander away from the car, huddling over some incomprehensible matter, Mary is left in the car to pay for the gas. When she goes to the bathroom, the others drive off without her. The whole scene is bathed in a brilliant white light in which the white gas station attendant watches the kids’ antics with a curious passivity. They seem to be putting on a show, and Tommy is indeed a showy character. The gang are all well-dressed and Cliff’s car is a sleek machine. As they smoke, drink, and carry on, the attendant’s gaze is caught in reverse-shot cutting as a kind of stand-in for the film’s audience.

The characters’ behaviour is not necessarily condoned by the filmmakers, but observed with a certain detachment. The film is not critical of the gender inequities but places them center-stage and casually incorporates them into its depiction of everyday life. Tommy’s misogyny is finally challenged when Clydean fights him off. Mackenzie himself seems to read the gender politics a little differently, further evidence of the temporal displacement of archival cinema. He says that he doesn’t believe in the scene, “either that the girl would resist that way or Tommy would give up that easily.” He wishes Tommy had “succeeded” in, presumably, “getting laid.” Curiously, he says the scene is “unreal,” although it is not clear whether it was the script or the improvisation that he lost control of.[26] In this way the film manages to avoid moralizing and commentary, adhering to the aesthetics of detachment and objectivity that later came to inform the practices of observational cinema. Only a few years later, in 1966, an ethnographic film program was established at UCLA by Colin Young. Some of the first students included Judith and David MacDougall, Herb Di Gioia and David Hancock. Like Mackenzie and his cohort at USC a few years earlier, they were inspired by neorealism and hoped to “reinvent” cinema.[27]

Among the various proponents and accounts of observational cinema that emerged from this school, Herb di Gioia has been singled out in a recent history as a key figure in the training of visual anthropologists. Anna Grimshaw and Amanda Ravetz describe his approach as:

Working observationally heightened the sense of the integrity and uniqueness of lived experience, an integrity stolen as it were from the continuous flow of daily events. The challenge was to seek out revelatory moments, those flashes of connection between what would otherwise be lost to flux.[28]

This account of observational cinema is evocative of Benjamin’s theory of the dialectical image as the crystallization of present and past. The images that break up the continuity of historical progress, such as those in the non-linear structure of the compilation film, produce a dialectics of awakening. While observational cinema is more typically a realist aesthetic, it also operated according to a logic of revelation, recognition and emergence.

Mackenzie’s process was precisely to reveal the uniqueness and integrity of the Bunker Hill Indians, taking years to hone down the material to a succinct 72 minutes. In an attempt to “reinvent cinema” Mackenzie and his crew ironically predated the advent of portable equipment and vérité strategies by only a few years. The nagra tape recorder was not available to filmmakers until 1962. This is yet another of the many untimely historical ironies of the film: the filmmakers from USC attempted to accomplish something similar to cinema vérité (or direct cinema as it was called in the States) using non-portable, non-synch, industrial equipment. They wanted to capture the spontaneity of everyday life, even if they had to re-stage it and coax it out of their non-professional actors/subjects. Jean Rouch was conducting similar experiments in France with films like Moi un Noir (1958), and Lionel Rogosin was likewise working with proto-observational strategies in New York around the same time with On the Bowery (1957). Although other filmmakers such as Rouch were using hand-held cameras in the 1950s to achieve intimacy with documentary subjects, Mackenzie’s crew did not choose that route, probably because of the lighting challenges of their chosen locales. The style of their film was in many ways governed by the specific night-time experiences they wanted to capture.

Despite his cumbersome equipment, there are in fact a number of passages in which Mackenzie was able to pick up some unplanned and unscripted footage. The bar scenes are all populated with extras, who are simply bar patrons going about their business. In one sequence, two men are dancing, clearly gay men who seem to be as at home in this marginal place as the Indians. The handheld camera captures their fancy footwork along with their joyful, relaxed faces.[29] This footage is intercut with shots of Homer drinking alone in a corner, fuming and prepping for a fight. When he finally goes for it, the provocation seems to be a man hitting on a girl, and not the gay men, who are there as part of the general atmosphere and expression of the L.A. nightlife. This accidental footage points to the possibilities of cinema vérité that were just around the corner with the introduction of portable sound and film equipment. Nevertheless, Mackenzie’s approach to his material, trying to improvise as much as possible within scenes staged to capture “typical” activities, comes close to that sense of revelation that is so key to successful examples of observational cinema.

On the soundtrack, the voice-overs of the three principle actors are delivered in a distinctive “reservation” accent, which Alexie notes, may be the first time these voices were heard in the movies.[30] Mackenzie’s choice of music for the film is a key element in its evocation of the “feeling” of the time and place. He wanted to use as much of the rock and roll that the Indians were actually listening to, but because he could not afford the rights, he contracted one band, The Revels, to record all the music for the film, including the radio commercials. They recorded 20 tracks, including a variety of musical genres that played on the radio and juke boxes of the time, giving the film a lively energetic upbeat character. The music itself conveys the revolutionary sense of social change associated with the youth culture of the late 1950s. And yet, again, it is largely with the clarity of retrospective vision that audiences can now understand the full impact of these changes in popular culture that were “infecting” America during this period. The Indians were the James Deans, Marlon Brandos and Shirley MacLaines of their generation, but nobody knew about them. The Revels themselves were a forgotten band until they were revived on the soundtrack of Pulp Fiction in 1994.

A Revolutionary Film

The “revolutionary” character of The Exiles is not due to its originary status, because it did not start a movement or even belong to one. Its revolutionary character is due to its status as an historical marker of unrealized possibility, the way that it records the untimely dynamism of the might-have-been. It is not only a portrait of a particular group of people at a particular moment in time; its sheer novelty as a “document” made it virtually invisible, and yet also potentially explosive.

When Andersen includes an excerpt of the gas station scene in Los Angeles Plays Itself, alongside gas stations in Kiss Me Deadly and Messiah of Evil (Willard Huyck, 1973), he says in his voice over narration:

Of course, there are certain types of buildings that aren’t designed to last. They must be rebuilt every five or ten years so they can adapt to changing patterns of consumption. So the image of an obsolete gas station or grocery store can evoke the same kind of nostalgia we feel for any commodity whose day has passed. Old movies allow us to rediscover these icons, even to construct a documentary history of their evolution.

Concerning Mike Hammer’s reel-to-reel answering machine in Kiss Me Deadly, Andersen notes, “What was new then is still with us.” This sequence of Los Angeles Plays Itself culminates in a scene from The Disorderly Orderly (Frank Tashlin, 1964) featuring the spectacular implosion of stacks of cans in a supermarket. In other words, the “antiquity” of the 1950s is an antiquity of novelty. Commodity capitalism has to continually reinvent itself, a process that, in retrospect, can constitute a kind of awakening or demystification of “progress.”

The Exiles incorporates Indians into the language of modernity, into the glow of the city and the energy of its novelties, challenging the conventions of both narrative and documentary cinema, as well as the not-yet-constituted principles of observational cinema. Despite Andersen’s attempt to frame it as neorealist, the film radically eschews any kind of Bazinian aesthetics of long-take deep-focus realism, indulging instead in dramatic editing and pacing, with close-ups of the principle actors guiding the narrative. Fast cars and lonely nights, memories and desires, as well as a desperate embrace of the moment charged with the “now-time” of the present: these coextensive experiences of time are also evidence of the failures of modernity to accommodate the Indians and their aspirations. The failure of the film to attract an audience in its own time, further points to the real failure of 1960s America to understand the desires invested in the power of expression of Mackenzie’s cinematic tribute to his friends in the city. Even if his avowed friendship with Tommy, Homer and Yvonne was inevitably conflicted with his offer to make them movie stars, he nevertheless attempted to give them a voice and a presence in the modern world.

Once we consider Los Angeles Plays Itself as an archival film, it is apparent that it creates the conditions for understanding The Exiles, precisely by creating the categories and classifications necessary for knowledge. For Foucault the archive “is that which, at the very root of the statement-event, and in that which embodies it, defines at the very outset the system of its enunciability.” The archive does not collect “the dust of statements that have become inert once more, … it is that which defines the mode of occurrence of the statement-thing: it is the system of its functioning.”[31] Andersen effectively places Mackenzie’s film within a language of the city, architecture, film history, and cultural history; by placing it side-by-side with Kiss Me Deadly, he is grasping the image from within, from its discursive formation and not from its humanitarian objectives or anthropological fumblings. In keeping with Foucault’s notion of the archive, Los Angeles Plays Itself “deprives us of our continuities” and it “breaks the thread of transcendental teleologies.” [32] And it does so precisely by grasping the image from a movement in its interior, which is how Benjamin describes the “historical index” of the image—what distinguishes it from the essences of phenomenology.[33]

Although Andersen also links The Exiles to Killer of Sheep (1981) by Charles Burnett, Burnett did not know about The Exiles when he made his film about an African-American working class neighbourhood in L.A..[34] The “problem” of The Exiles is that it exists outside any spheres of influence. Mackenzie was not aware of Rogosin or Rouch; likewise neither Cassavetes nor Burnett, not to mention The Maysles and Fredrick Wiseman, knew about him. Cinema was being “re-invented” all over the world during the 1950s in disparate ways and The Exiles is anomalous in its glamorous re-enactment of classical film techniques in the service of ethnography, and so its “dirty realism”, as Sherman Alexie calls it, is not really as dirty as On the Bowery or Moi, un noir, or even Salesman (Maysles Brothers, 1968) for that matter. It therefore arguably remained illegible until it was placed side-by-side with Kiss Me Deadly as a film about a city.

The emergence of the new generation of Indians, challenging the norms and protocols of their parents’ generation is set against the radical transformation of urban renewal in The Exiles. The redevelopment of Bunker Hill in the 1960s is described by Greg Kimball as “the largest urban renewal project in history,” and indeed the political background to the project is an ugly story of capital investment displacing public housing on an exaggerated scale. Residents were relocated with a pittance of support, and the century-old homes were razed to a naked hump of a hill. The reconstructed Bunker Hill includes such cultural monuments as the Museum of Contemporary Art, Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall, and the Bonaventure Hotel, and Anderson cites it as the location of a series of post-apocalyptic fantasy movies such as Omega Man (1971), Night of the Comet (1984) and Virtuosity (1995). Other nearby neighbourhoods and landscapes, including Hill X, were similarly razed during the 60s and 70s as L.A. sold itself to international capital to claim a place in the global marketplace. Most of the displaced people were Mexican and Asian immigrants, seniors and Indians—people already displaced from their original homelands.[35]

John C. Portman’s Bonaventure Hotel, constructed in 1975, was famously described by Fredric Jameson as the emblematic “postmodern hyperspace,” and the Bunker Hill redevelopment can be compared on some levels to Baron Haussmann’s reconfiguration of Paris in the nineteenth century. For Walter Benjamin, Haussmann’s urban renewal project (which may actually have been larger in scope than the Bunker Hill project) created the conditions for flânerie and the display culture of the Arcades. But the Bonaventure Hotel clearly shuts down these possibilities, radically cutting off the “private space” of the hotel from the public space of the now deserted streets. The faux-public spaces of the hotel’s interiors, including a nostalgic recreation of L.A. as garden, is radically separated from the city, as Mike Davis has pointed out.[36]

Davis has challenged Jameson’s embrace of the Bonaventure Hotel as a postmodern Utopia. The parallels between the Bunker Hill gentrification project and Benjamin’s analysis of the Paris Arcades have to include the displacement of urban populations that made way for two different kinds of display cultures. For Davis, the Bonaventure Hotel symbolizes a profoundly anti-urban impulse, “hardly a possible entryway to the new forms of collective social practice towards which Jameson’s essay ultimately beckons us.” [37] Jameson concludes his essay with a question about “whether postmodernism can resist the logic of consumer capitalism?” A film like The Exiles points in this direction, and perhaps it is best read as an untimely postmodern film (avant la lettre). The “truth” of the Indian experience is apprehended through the transformation of their everyday life into the phantasmagoria of image culture; but this is the truth of their hopes and dreams, their sorrows, and their disappointments. It is a language of affect and melodrama, even if the drama is downplayed and distended. Thom Andersen may position the film as an antidote to the simulacrum of the city; and yet, the techniques of re-enactment in which every shot is staged are precisely those of the postmodern simulacra. In their profound inauthenticity, the “exiled” Indians perform their own impending displacement by corporate capitalism.

And yet there is a larger drama being played out in the untimeliness of this idiosyncratic film. The obliteration of the Bunker Hill neighbourhood, the displacement of native populations, and indeed all the “losses” of modernity, find archival form in the early 21st century in a new form of memory. Films like Los Angeles Plays Itself point to the ways that the cinema has spawned a new medium of archival cinema. Traces of the past, culled from the vast repertoire of 20th century culture, can be recombined to write a new history of the 20th century. The Exiles in this sense depicts a culture of alcoholism, poverty, and sexual politics; but it also inscribes its characters into a larger firmament of popular culture. The Indian characters are no longer outside looking in, but a full part of the generational energy that surged through American culture in the 1950s.

The only critique of The Exiles I’ve come across is Manohla Dargis, who points out that the film keeps the Indians in the dark, with no exit. She describes the film as “postcolonial noir,” borrowing a term from Norman M. Klein, which evokes the tone of the film very well.[38] I would argue that the film also bathes its characters with the glow of Hollywood, and that their return to darkness is in keeping with the documentary “truth” of real poverty, alcoholism, and displacement. For a critic to even propose a Hollywood ending for these people on the margins is evidence of the desires that the film opens up through its idiosyncratic techniques. On the other hand, the enthusiasm and intelligence of a self-appointed spokesman for native identities, Sherman Alexie, in the “new” archive assembled by Milestone, points to the outside of that older archive of despair.

The archive in the early 21st century has become a dynamic site of reconstruction, reordering and re-animation of the past. The walls are crumbling and the memories of unheard voices are rushing in. When Benjamin says that, “the concept of progress must be grounded in the idea of catastrophe,” he points to the radical potential of a film such as The Exiles to interrupt the story of cinema, of Bunker Hill, ethnographic film and the noir mystique. “Phenomena,” he says, are rescued from “‘their enshrinement as heritage.’- They are saved through the exhibition of the fissure within them. -There is a tradition which is a catastrophe.”[39] The archive is always predicated on loss, and the division between that which is inside and that which is outside. But for Derrida, there is an archival drive, which he finds already in the psychoanalytic dispositif; in the archival cinema discussed here, that drive is clearly linked to the desires embedded in narrative cinema.

What we can learn also from a film like The Exiles, is how archival desire is manifest in the black-and-white phantasmagoria of the Hollywood image-machine. It has the power to evoke an intimacy and closeness with America’s first peoples that few would have imagined possible. In this sense, Benjamin is exactly right when he says, “the historian is the herald who invites the dead to the table.”[40] One of the most poignant moments in the audio recording of the premier of the restored print of The Exiles in 2008 is when Yvonne, who has come to the screening, asks where Kent is. She is told that he passed away 18 years ago, and we realize how remote her world remains from that of the cinephiles gathered to celebrate the film.

Seeing The Exiles as a restored, heavily annotated DVD release, or excerpted in Thom Andersen’s melancholic treatise on L.A., one is confronted with ghosts. But these are ghosts with whom we can communicate precisely because they are ensconsed within a phantasmagoria that still enchants. The sensory detail of the film—including its soundtrack music—enables us to engage with the people and the city on a cinephiliac level. Through our ability to share a certain kind of non-intellectual, sensual experience of light, sound, speed and style, we can better grasp the sense of lost possibility, historical incompletion and “unfulfilled beginnings” that are implicit in The Exiles. This is precisely the utopian edge of the untimely phantasmagoria that Benjamin sought to recognize and document in his study of Paris.

Archival cinema renders film untimely and exploits its untimeliness through temporal displacement and fragmentation. As the example of The Exiles demonstrates, this untimeliness may enable a film to find new audiences, and its documentation of a now-time allows a present-tense to become legible in all its immanence. The phantasmagoria of cinema offers a sensory experience of the past renewed in the present, an untimely present-tense that Benjamin might recognize as a kind of awakening from the nostalgia of lost cities and lost peoples, and a recognition of their failed promise. In The Exiles, the dynamic energy of 1950s popular culture, including rock and roll, noir cinema and car culture encompasses the image of Indians in the city, offering a rare glimpse of a key moment in American cultural history.

WORKS CITED

Andersen, Thom. “This Property is Condemned,” Film Comment 44 (2008).

Antin, Eduardo (Quintín). Cinema Scope 36 (2008).

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Benjamin, Walter. “Excavation and Memory.” In Selected Writings Vol. 2, edited by Michael W. Jennings. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard, 1999.

Brody, Richard. The New Yorker, September 15, 2008.

Chaput, Luc. “The Exiles,” Sequences Mai-Juin, 2009.

Charity, Tom. Sight and Sound 20 (2010).

Cocker, Emma “Ethical Possession: Borrowing From the Archives,” Scope 16 (2010) http://www.scope.nottingham.ac.uk/cultborr/chapter.php?id=9

(accessed June 12, 2011).

Dargis, Manohla. “Despair and Poetry at the Margins of Society,” The New York Times, July 11, 2008.

Davis, Mike. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. London: Pimlico, 1998.

Davis, Mike. “Urban Renaissance and the Spirit of Postmodernism.” In Postmodernism and its Discontents: Theories, Practices, edited by E. Ann Kaplan. London: Verso, 1988.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Trans. Eric Prenowitz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Foucault, Michel. “The Historical a priori and the Archive.” In The Archive, edited by Charles Merewether. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2006.

Garson, Charlotte. Cahiers du Cinéma, 651 (2009).

Grimshaw, Anna and Amanda Ravetz. Observational Cinema: Anthropology, Film, and the Exploration of Social Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Mackenzie, Kent Robert. “A Description and Examination of the Production of The Exiles: A Film of the Actual Lives of a Group of Young American Indians,” MA Thesis, University of Southern California (1964).

Naremore, James. “Films of the Year, 2008,” Film Quarterly 62 (2009).

Russell, Catherine. Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.

Spieker, Sven. The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

Verwoert, Jan. “Apropos Appropriation: Why Stealing Images Today Feels Different,” Art & Research 1 (2007) http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/verwoert.html.

Wees, William. Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films. New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1993.

[1] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 460.

[2] Sherman Alexie refers to a “battered VHS copy” that he saw as a student, which was very likely a non-commercial transfer of the print in the USC archive, as there is no evidence of a commercially-released VHS version of the film. Sherman Alexie and Sean Axmaker, Second Interview: Audio Bonus Feature in The Exiles (Milestone DVD release, 2008).

[3] The text of Thom Andersen’s narration (which is spoken in the film by Encke King) is transcribed at: http://filmkritik.antville.org/stories/1071484/ (accessed June 12, 2011). Although Andersen dates the film as 1962, the Milestone materials date the first theatrical release as April and May 1961.

[4] Compilation film practices can be traced back to the 1920s with work by Esther Schub and Walter Ruttman, but it was not until the postwar period and films such as Night and Fog (Resnais, 1955), that the found footage mode took on political and critical forms of address. See my chapter “Archival Apocalypse” in Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999); and William Wees, Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1993).

[5] Walter Benjamin, “Excavation and Memory,” in Selected Writings Vol. 2, ed. Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard, 1999), 576.

[6] Benjamin, Selected Writings, 576.

[7] Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

[8] Sven Spieker, The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008).

[9] Spieker, 173-74

[10] Spieker, 114.

[11] Jan Verwoert, “Apropos Appropriation: Why stealing Images Today Feels Different,” Art & Research 1, no. 2 (2007): 3.

[12] The text of Thom Andersen’s narration (which is spoken in the film by Encke King) is transcribed at: http://filmkritik.antville.org/stories/1071484/ (accessed June 12, 2011).

[13] Emma Cocker, “Ethical Possession: Borrowing From the Archives,” Scope 16, February 2010, http://www.scope.nottingham.ac.uk/cultborr/chapter.php?id=9

(accessed June 12, 2011), 4.

[14] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 15.

[15] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 19.

[16] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 460.

[17] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 463.

[18] In Mackenzie’s documentation, and also in the recently recorded commentaries on The Exiles, the American terminology of “Indians” is used systematically and without quotation marks. Sherman Alexie claims in his interview on the Milestone disk that he prefers the term “Indian” to “Native American,” as it is the term he grew up with and identifies with. In Canada this term has long been replaced by either “First Nations” or “Native Peoples,” but I have chosen to use Mackenzie’s term throughout the paper in keeping with the terminology in the texts under discussion.

[19] The Exiles Press Kit, Milestone DVD release, 2008. Included as PDF file in DVD package.

[20] Kent Robert Mackenzie, “A Description and Examination of the Production of The Exiles: A Film of the Actual Lives of a Group of Young American Indians,” MA Thesis, University of Southern California, 1964, 156.

[21] “Final Cut 2008: Terra Incognita: Unknown Pleasures from Around the World,” Film Comment 45, no. 1 (January 2009): 41-45; James Naremore, “Films of the Year, 2008,” Film Quarterly 62, no. 4 (July 2009): 26-27.

[22] “Staff recommendations: Cineaste editors tout their favorite DVD releases,” Cineaste XXXV:2 (Spring 2010); Tom Charity, Sight and Sound 20, no. 2 (2010): 86. Charlotte Garson, Cahiers du Cinéma, 651 (2009): 75; Antin, Eduardo (Quintín); Cinema Scope 36 (2008); Richard Brody, The New Yorker September 15, 2008, 84, no. 28: 22; Luc Chaput, “The Exiles,” Sequences Mai-Juin 2009: 260.

[23] Brody, 22.

[24] Thom Andersen, “This Property is Condemned,” Film Comment 44 no. 4 (2008): 38-39.

[25] Andersen, 39.

[26] Mackenzie, MA Thesis, 99.

[27] Anna Grimshaw and Amanda Ravetz, Observational Cinema: Anthropology, Film, and the Exploration of Social Life (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 55.

[28] Grimshaw and Ravetz, 119.

[29] In the audio recording of the panel discussion at the theatrical release in 2008, one of the participants, either Eric Darstaad or Robert Morrill who were both in attendance, notes that he and the other two principle cameramen had been drafted (for the Korean war) and this footage was shot by someone else.

[30] Sherman Alexie, “Second Interview” with Sean Axmaker, Audio special feature, The Exiles Milestone DVD, 2008.

[31] Michel Foucault, “The Historical a priori and the Archive,” in The Archive, ed. Charles Merewether (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2006), 29.

[32] Foucault, 30.

[33] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 462.

[34] Burnett was not aware of Mackenzie’s film until Thom Anderson brought it to his attention. In a radio interview, he says that after reading Mackenzie’s notes, he realized that they were working towards the same ideas about filmmaking, although Mackenzie did so ten years earlier than he. (WNYC Leonard Lopate Show with Sherman Alexie, Charles Burnett and Denis Doros. Audio Bonus Feature on Milestone DVD release of The Exiles.)

[35] Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (London: Pimlico, 1998), 72, 74.

[36]Mike Davis, “Urban Renaissance and the Spirit of Postmodernism,” in Postmodernism and its Discontents: Theories, Practices, ed. E. Ann Kaplan (London: Verso, 1988), 86.

[37] Mike Davis, Urban Renaissance, 87.

[38] Manohla Dargis, “Despair and Poetry at the Margins of Society,” The New York Times, July 11, 2008: 12.

[39] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 473.

[40] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 481.