Writing in early 2012, while the Syrian army besieges whole towns and racks up a death and injury toll of thousands, is it ill-judged to train focus on this country’s cinema heritage, rather than immediate humanitarian concerns? Moreover, it might seem positively distasteful to dwell, as I intend to, on some of the Ba‘ath regime’s laudable contributions to the field of film production. Such a perspective should in no way be interpreted as support for Syria’s leadership. Amongst the countless other atrocities of the past year, government forces arrested (and later released) several state-employed directors, including Mohammad Malas and Nabil al-Maleh, during the July 2011 Intellectuals’ Demonstration, and, that November, filmmaker Nidal Hassan was detained for over a month after a routine visit to collect his passport for a trip to an overseas film festival.[1] It should go without saying that this article condemns such actions and their motivations.

That said, we should be wary of pushing for a Year Zero approach to the Syrian revolution. As a line of anonymous medieval graffiti warns from its home in Edessa church (once in Syria, now in Turkey, along with a multitude of new refugees): “Time has a habit of exiling chosen persons.”[2] Such remnants of vandalism represent history at its most illegitimate, some would say anti-social. But, despite the fact that this sentence was scrawled more than a thousand years ago, it still feels timely. How and why are certain documents from the past preserved, as both objects and as pertinent contributors to contemporary chronologies? This centuries-old statement highlights just how frequently time-in-the-abstract unfairly shoulders the blame for human history-making’s doggedly political actions, its banishment of people, ideas and ways of living that contradict an ascendant mode of governance. In the case of contemporary Syria, the uprisings against the Arab socialist autocracy may or may not result in the country absorbing greater democracy and neo-liberalism. Whatever their outcome, conflicting ideologies are at war here and such upheavals are always driven by the aim of casting something off, discarding it as untimely. What should stay, and what, or whom, should be exiled?

Syrian cinema already exists as one such casualty of history and is in danger of remaining so within the discourse to come on its homeland. For over forty years, the Syrian National Film Organization has been responsible for a number of stylish, provocative, politically-nuanced, yet state-sponsored films created according to a not-for-profit model. However, few of us have ever been afforded the opportunity of viewership. The National Film Organization’s contestation of dominant, exploitative narrative trends and modes of production, I shall argue, is all the more worthy of our consideration right now, even if, in many senses, Syrian state cinema can be construed as an organ of an abhorrent regime, and despite the fact that film culture may not, at first, appear a necessary priority within the fight for equality and freedom in the Arab world and beyond.

In her essay, “Untimeliness and Punctuality: Critical Theory in Dark Times,” the political scientist Wendy Brown pays particular attention to comparable moments of urgency and how critiques and complications of unequivocal exigencies are rebuffed with a “now is not the time to get bogged down in quiddities.” The drawing up of priorities – of what is pressing and what is not – thus earmarks any number of propositions and practices as marginal or redundant. With the denunciation of Ba‘athism, one wonders at the side-lining of the welfarism that endures alongside the ruthless violation of many other human rights. In the company of Friedrich Nietzsche and Walter Benjamin, Brown insists that muffled remnants from a past or passing political system can snag the close and seamless weave of a prejudicial fabrication of politics and history.[3] She argues:

If the charge of untimeliness inevitably also fixes time, then disrupting this fixity is crucial to keeping the times from closing in on us. It is a way of reclaiming the present from the conservative hold on it that is borne by the charge of untimeliness.[4]

My analysis aspires to make similar interjections and it does so in solidarity with Syrian cinema as both industrial and textual practice. In these realms, Syrian cinema itself, since its very inception, has stood as committedly untimely in response to the authority of colonial, capitalist and neoliberal rule elsewhere.

By the day, persuasive discourse and concrete legislation, including the imposition of sanctions by the Arab League, is being churned out in condemnation of the Ba‘ath Party, readily piling up evidence of and materially enforcing its untimeliness. What this article endeavours to tease out are some of the regime’s more laudable accomplishments, lest a current of free market transformation try and sweep them away, all in the name of a highly complicated, even destructive notion of “progress.” One such achievement might be identified as a film industry (in fact many sectors of employment) that upholds much more benevolent working conditions than those familiar to us in “the West,” most markedly, stable wages regardless of shooting schedules, legally-upheld maximum working hours and full pensions. Concurrently, Syrian filmmaking has stood defiantly in the face of the forces of transnational oligarchies and their concentration on exploitative profit-making. There are precious few examples of this left within cinema culture across the globe, so Syrian cinema’s untimeliness opens out onto a wealth of possibilities for us to imagine movies and their conditions of manufacture otherwise. Their filmmaking has operated according to perhaps more humane modes of production, however paradoxical that may seem within contemporary inscriptions of Syria. These factors unsettle the path beaten by the prevailing currents of change in two ways. Firstly, they question whether free trade really does offer the most advantageous means of social betterment. Secondly, Syria’s arguably more pleasant working environment (in cinema and beyond), coaxes a redressing of how capitalist definitions of “advancement” consistently place countries like Syria in a defensive position, maybe all the better for other nations to intervene and financially exploit them.

Syrian movies themselves, within their very story-lines, regularly expose these kinds of social injustices. They dedicate their efforts to the kinds of narratives with which movie production and programming, so often guided by the tyrannies of entertainment, has dispensed. We acquaint ourselves with: farmers (Verbal Letters (Abdullatif Abdulhamid, Syria, 1991)); religious minorities (Al Lajat (Riad Shaya, Syria, 1995)); bit part players (The Extras (Nabil al-Maleh, Syria, 1993)); domestic abuse sufferers (Dreamy Visions (Waha al-Raheb, Syria, 2003)); rape survivors (Stars in Broad Daylight (Oussama Mohammad, Syria, 1988)); and refugees from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights (Something is Burning (Ghassan Shmeit, Syria, 1993)), Palestine (Red, White and Black (Bashir Safiya, Syria, 1976)) and Iraq (The Tissue Vendor (Mohammad Malas, Syria, 2009)). Barely a glimpse of the rich and powerful is to be savoured, except when they loom in as corrupt aggressors to these sympathetically-portrayed protagonists. The characters inhabit a leftist subaltern topography that differs wildly from the bourgeois vistas of much globally-distributed movies. Like so much graffiti, the details of lives such as these are customarily expunged from orthodox cinema and history both. And, while these protagonists have long been commonplace within Syrian cinema, the movies have not stalled within a complacent representational agenda: they continue to probe issues that are considered untimely within their own country too. Sacrifices (Oussamma Mohammad, Syria, 2002), for example, brings us a character returning from the conflict with Israel, someone who has seen female conscripts amongst his enemies and wonders why the Arab world cannot countenance such roles for women. A pronouncement about superior equal rights through a balanced concession to Syria’s mortal adversaries is quite some proposition. In addition, and almost as a matter of course, Syrian movies are sharply disparaging of many elements of Ba‘athist rule. A sizeable and growing number of the state’s film sector employees have compiled or signed a recent online petition which denounces the Ba‘ath Party’s responses to the uprisings, claiming, amongst other things, that they “believe that a reform which does not start with putting an end to security forces [sic] control over our people’s lives and bodies, and with closing an era of shameful political imprisonment for good, is not enough.”[5]

When the army and security forces are cracking down so aggressively, less courageous people might regard their declarations as untimely, not really in their individual best interests.

What Syrian cinema elucidates about the untimely on the textual level also echoes through the industry’s mode of production, one under threat during the current period of civil unrest. Taking the untimely seriously here can help ward off reform’s throwing out of the baby with the bathwater. How exactly, then, does Syrian cinema function? Since independence, a significant proportion of it has been produced under the auspices of the National Film Organization, a state-run, not-for-profit enterprise whose employees hold permanent, full-time civil service contracts. This set-up is itself untimely, an orphan of Warsaw Pact film culture, which helped instate Syria’s own public sector industry by providing training and distribution support. The spectral presence of Eastern Europe invites an analysis of contemporary Syria in light of post-1989 transitions, allowing us to learn from some of the mistakes that were made then. This legacy creates an application of history as reciprocal, emphasizing the possibility for global coalitions (such as those between the former second world and non-aligned nations) while simultaneously underscoring, through Syria’s isolation, how and why these links have been dissolved. The shrinking ambits of Syrian cinema have similarly prompted a wane in its audiences, given that the theatres of Sofia, Bucharest and Moscow no longer welcome it with regularity. A new international fan base is hard to drum up when next to none of these movies have been released commercially, a situation which then side-lines this oeuvre just as much as the subject matter it esteems. Syria’s cinema clubs have also lost out to home viewing of television serials and pirated DVDs. Gone, largely, are these public fora, lost to a different form of sociality, one that is private, frequently family-, rather than community-oriented. Yet still the anachronism lives on – just, and for who knows how long, especially if civil war and marketization grows apace in Syria. The NFO’s slow and meticulous methods, I shall point out, sit uneasily within the pacing of rationalized movie production. Nor, as has been observed, does the NFO favour broadly saleable topics, preferring to grapple with issues like incest and refugee rights, as well as direct critiques of the government that currently funds it. Almost none of the movies the NFO make could be considered propagandistic; on the contrary, they tend to stand against the unswerving dogma typically associated with comparable dictatorships.

That task of proselytizing has been more efficiently carried out by other Ba‘ath Party actions. Predicable government organs include state television, rallies and awnings, but also the actual and symbolic treatment of territory. The town of Quneitra, to the south of the country and near the border with Israel, has changed hands between the two countries several times, culminating in much of it being razed as Israeli forces beat their retreat in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Now sheltered by a United Nations Disengagement Observer Force, Quneitra is under Syrian jurisdiction, but preserved as a barely-populated ruin, “museumified” as a relic of blame at the expense of Quneitra’s refugees, most of whom are barred from resettling. Significantly, though, Quneitra as it once was is the setting for a good number of Syrian movies. The willful suspension of Quneitra, the disinclination to exploit its resources for basic and immediate material use-value or profit, invokes the suggestive political power of non-productivity, something, as will become clear, that Syrian state cinema also does. Ironically, the perceived threat of Israeli invasion also sanctioned the imposition of emergency law in Syria. Typically, this is considered a pressing, but temporary means of administration in desperate times. In Syria, emergency law reigned from 1962, rescinded only after the first wave of protests in April 2011. As both an anti-colonial declaration against Israel and a curtailment of its citizens’ rights in favour of military rule, emergency law became as ossified as Quneitra itself. It has also funneled funds for the arts away to the arms industry.[6] These stultifications conform to the Moroccan thinker Mohammed Abed al-Jabri’s pre-uprising disparagement of Arab society and historiography:

The temporal in recent Arab cultural history is stagnant… for it does not provide us with a development of Arab thought and its movement from one state to another; instead, it presents us with an exhibition or a market of past cultural products, which co-exist in the same temporality as the new, where the old and new become contemporaries. The outcome is an overlapping between different cultural temporalities in our conception of our own cultural history… This way, our present becomes an exhibition of our past, and we live our past in our present, without change and without history.[7]

Al-Jabri’s compatriot, the historian Abdallah Laroui, stratifies these monumental and official temporal remnants. He does so in an attempt to detach reform from conservatism:

[I]f you want to be an actor in the social process you have to decide between traditionalism and historicism. Both of them are ideologies, ways of interpreting social realities, but the fact is that traditionalism cannot help modernise society even if it can revolutionise it, while historicism can.[8]

Filmic representations of Quneitra are frequently historicist, figured as complex and persistent reminders of explicit moments in time, rather than eviscerated of their contexts. These untimely flashpoints on the Syrian landscape thus obtrude and begin to conduct meaningful political work. Here, Quneitra emerges as something of a phantom limb, a palpable and intermittent presence within dreams, deliria and reminiscences, materializing in a variety of incarnations. It does so to remind Syria of not only the anguish suffered when territory is captured by the enemy, but also the government’s unhonoured duty to the Golan refugees. These unhinged and unresolved histories frequently bleed into each other, as happens during the opening sequence of The Night (Mohammad Malas, 1992, Syria) when Wissal’s voiceover from the present (where she is a refugee) clings to her simultaneous, but diegetically-tethered and embodied dialogue, which is situated in pre-conflict Quneitra. Elizabeth Grosz, under the influence of Nietzsche, and not referring to cinema specifically, offers insight into these types of overlay:

This access to the out-of-step can come only from the past and a certain uncomfortableness, a dis-ease, in the present. The task is to make elements of this past live again, to be reenergized through their untimely or anachronistic recall in the present. The past is what gives us that difference, that tension with the present which can move us to a future in which the present can no longer recognize itself.[9]

The Night later recreates Golan spaces in pronounced and unbroken ways, the camera carefully exploring, but also lingering, as if to re-acquire every inch of surrendered territory and proudly showcase Quneitran heritage. As its director reveals “I was looking for a lost place, namely, Quneytra, the village destroyed by Israel. I reconstructed it and recovered its life, cinematically.”[10] The documentary imperative also emerges in Something is Burning when a family photo of the Golan (a rare, concrete record of ownership) melts into a pre-war flashback. On another occasion, the movie logs one of the uncommon visits refugees are allowed to make to the border, from where they greet their estranged neighbours across a barbed wire fence. “A stone’s throw separates me from my house. Who’d have thought we’d be away for so long?” muses the protagonist-patriarch, Abu Ramzi, cuing a flashback scene of his youthful self gamboling through an orchard. A good handful of these returns-to-the-past conjure the Golan as a rural idyll and one might be forgiven for initially reading them, according to Laroui’s distinction, as nostalgic traditionalism. The camera movements are fluid and uninterrupted; long pans unify various agricultural activities such as olive harvesting and grape-treading. Cranes enable a sweeping over, surveying and recapturing of multiple planes of the countryside, summoning lands beyond its makers’ and audience’s reach and imploring the renewed consideration of a means of return. However, these sections of The Night and Something is Burning work in dialogue, as Elizabeth Grosz would hope, with the present and the elsewhere, gracefully gliding backwards and forwards through time and space, their unnerving smoothness pointing to the affective mythification processes of cinema and history alike, as well as the possibility of unhindered return.

The films achieve this precisely by, on other occasions, enforcing their untimeliness through sharp stylistic schisms. Something is Burning does its best to recreate the disorientation of warfare and exile, the historicism that points to the geopolitical specificity of Israeli invasion that can serve to denaturalize emergency law. There are many instances when we do not know exactly where we are, and still more which are roughly and discontinuously latched together, jolting us from Quneitra of the past, to the desert, to inner city Damascus (in the films’ present). Plumbing the relational possibilities of editing, Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov (familiar to all these directors via their training in the Eastern Bloc) asserts:

thanks to montage, it is possible to create, so to speak, a new geography, a new place of action. It is possible to create, in this way, new relations between the objects, the nature, the people and the progress of the film.[11]

For Kuleshov, editing is dialectical, as the untimely can also often be. Montage roughly supplants the borderlands of the Golan with the desertscapes of another Syrian border, where one character, Ramzi, has taken up as a smuggler in order to escape the poverty of landless refugee life. By doing so, he transgresses into the spatial and moral fringes of Syrian society. Meanwhile, his law-abiding father, Abu Ramzi, can never feel truly at home outside his birthplace, his stunted life in Damascus underscored by a graphic match between a flourishing Golan tree and a flimsier city specimen, forlornly poking up through a concrete surround. Dramatic inter-cutting later plunks Ramzi’s desert-set murder of his villainous uncle, Abu Hamdi, next to scenes of bulldozers pummelling Ramzi’s father’s new home. The house has been built without a permit and only after years in temporary rental property prompted by Abu Ramzi’s inability to accept the family’s unlikelihood of ever returning home to Quneitra. The causes of these tragedies are one and the same, and utterly determined by the untimely delays of refugee existence. Keystones of traditional masculinity – decency, respect and provision for one’s family – crumble amidst a geography of displacement, one repercussion of the urge to maintain Quneitra as a ghostly memorial, rather than a dwelling place.

Such filmic proclamations enact an aspiration Walter Benjamin presents in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” By colliding past and present, a rupture opens up that can reveal an opportunity for revolution, which, in turn, contradicts the complacent and exploitatively ideological marshalling of historical narration. Gilles Deleuze leverages a subjectivity into all this, a political agency that involves merging:

back into the event, to take one’s place in it as in a becoming, to grow both young and old in it at once, going through all its components and singularities. Becoming isn’t part of history; history amounts [to] only the set of preconditions, however recent, that one leave behind in order to ‘become’, that is, to create something new.[12]

Deleuze’s call to action unites with Benjamin’s thinking here. Benjamin heeds the threat of “danger” as it might debilitate class struggle, and both authors profess faith in untimeliness as a propellant and mobilizing force. Here one might define this danger more specifically as the increasing infringement of film (and other) workers’ rights, not just in Syria, but globally. A real-world, embodied politics, a taking of one’s place, to quote Deleuze, is actualized through how labour is apportioned, defined and defended in this context.

One appeal of Syria’s untimely means of organizing film labour – protective, as will be revealed, in the face of the freelance hegemony – is that it is resilient. We do not have to dredge it from a buried past because it has still functioned until extremely recently, albeit obfuscated by the contradictory and obstructive intentions of much of the rest of the planet’s film production. This hardiness is, of course, what renders it untimely and might well allow us to carry it into the future, a rare and apt alternative within a period of post-socialist supremacy that often cannot even imagine a cinema that doubts capitalism, in infrastructure as well as form and content. For Jacques Rancière, these strategic dippings in and out of history are the very fabric of politics:

Each present may be grasped within a plot of temporality interweaving and possibly clashing different lines of temporality. And politics is one of those interweavings of time… It’s a broken history of forms of subjectivization, a time of promises, memories, reputations, anticipations, and so on.[13]

With this in mind, it makes absolute sense to strive to fulfil Benjamin, Laroui and Deleuze’s entreaties for revolutionary action – through rupture, through historicism, through becoming – congruous as they are with the actual functioning of politics.

How, then, does Syrian state cinema intermesh past, present and future formations of labour? Firstly, the NFO’s employees have been housed within the public sector, which, in recent times, has employed 58% of university graduates in urban areas and 75% of those in the countryside, providing them with job security, enhanced retirement benefits and shorter working hours than the private sector.[14] Under these conditions, civil servants could expect to retire at sixty and are not supposed to work for more than 42 hours per week.[15] Their salaries cannot match their equivalents in the realms of, say, western cinema, but they are 20% above the average government wage and, most importantly, they remain constant, regardless of production schedules.[16] As Syria’s economy grows more fragile, it should be noted that the International Monetary Fund, who may well come running to the rescue, have a penchant for blocking a nation-state’s own determinations of a minimum wage. Post-socialist history, a legacy to which Syria has been tightly and economically bound for decades, reveals that the kinds of subsidies that nourish state infrastructure are often sacrificed on the various altars of the ideologies of privatization and pragmatic cost reduction.[17] Real wages typically plummet as salary differentials, homelessness and health problems rise.[18] Should the NFO lose its government support, it would probably conform to the methods of most filmmaking elsewhere, where almost all casts and crews are freelance, unsure of where their next job will come from and rarely provided with complimentary pensions or healthcare. All these are the cost-cutting measures of the for-profit model, ballasted by free trade philosophy. On set, six day weeks are a norm and, in Britain, for instance, working days often run beyond twelve hours with less than a twelve hour turnaround for rest.[19] Certain sectors of postproduction, in the G-8 countries too, are referred to as “digital sweatshops” on account of their corner-cutting around overtime pay, benefits and sanctioned leisure (even sleep) time. In a climate where competition trumps all else, at every phase of manufacturing, the industry does what they can to undermine union rulings on fair pay, hours and compensation, to co-produce, off-shore or cannily subcontract to a number of smaller, less regulated operations, all the while demonizing collective organization.[20] Within socialism, whatever other criticisms it might prompt, high employment and welfare safety-nets are (or, more rather, were) routinely expected and trusted. Any call for freedom of speech, democracy, marketization and de-militarization in times of change for Syria should not be allowed to drown out these other similarly crucial human rights – the kind that often stand in the way of untrammeled capitalist accumulation and are as timely now as they ever were.

Syrian films uphold this belief in the importance of fair labour within both fictional and documentary registers. Our Hands (Abdellatif Abdulhamid, Syria, 1982), which consists almost entirely of close-ups, interweaves a panoply of manual tasks – from laboratory work and type-setting to cotton processing and book burning – with other social gestures, such as conversations in sign language.

Paid labour sits comfortably within the contexts of community and nation, never an unwelcome but financially-necessary intervention into more enjoyable activities. Watching this portrayal of work-as-social right now, while Syria disputes its future, helps recall transitions from socialism to capitalism that have already been weathered. Such adaptation does not simply involve replacing one political belief system with another, it brings about a profound transformation of how time is framed by and for a community and what it means on the inter-personal level. Summing up the core characteristics of what she terms post-communist nostalgia, Maria Todorova mulls over how the past continues to reverberate through attitudes to work:

it is not only the longing for [lost] security, stability, and prosperity. There is also the feeling for a very specific form of sociability, and of vulgarization of the cultural life. Above all, there is a desire among those who have lived through communism, even when they have opposed it or were indifferent to this ideology, to invest their lives with meaning and dignity, not to be thought of, remembered, or bemoaned as losers or “slaves.”[21]

Across a number of its expressive planes, Syrian cinema preserves these socialist ideals in a now-untimely fashion. To start out with, the typical Syrian worker and their activities gain much more screen time than they might elsewhere. Today and Everyday (Oussama Mohammad, Syria, 1986), a twelve minute, largely dialogue-free document of everyday life in the port city of Lattakia, necessarily dedicates the bulk of its time to the toils of bakers, fishermen and construction workers. Even when these figures are not visible on screen, they are present on the soundtrack. A momentary disjunction of sound (the thump of a hammer on an anvil) and image (citizens grocery shopping) draws manual labour into every aspect of daily activity, refusing to conceal the travails of manufacturing, particularly at the point of consuming its products.

Yet perhaps the group of Syrian workers most immortalized within Syrian cinema are those grafting within the rural economy, with the farm as the primary location for Al Lajat, Stars in Broad Daylight, Verbal Letters, The Chickens (Omar Amiralay, Syria, 1977), Nights of the Jackal (Abdullatif Abdulhamid, Syria, 1989), and Listeners’ Choice (Abdullatif Abdulhamid, Syria, 2003). Adroit camera movement and careful composition engross the farmer-protagonists with the soil they work. Nights of the Jackal’s second scene commences with a dexterous four minute, 35 second single take. First, the camera performs a slow, almost 360 degree pan across the rural vista before wandering through the protagonists’ farm, locating each character as they gird themselves for a day in either the fields or the household. This sequence is one of many content simply to leave the workers to get on with quotidian tasks. The seemingly humdrum is near-sanctified by the generous screen time apportioned. Furthermore, the temporalities of rural work often dictate the pacing of the movies. The annual rhythms of different harvests function as chapter markers in Nights of the Jackal, while its soundtrack is evenly punctuated by the repetitive noises of local manual labour: grinding corn, churning butter and such like. Routine farm tasks consume the bulk of Al Lajat’s first act, a movie that stresses the cyclical character of agricultural time and links its protagonists to elemental forces through Salma’s repeated voice over “wax and wane, wax and wane.” A politically-utilitarian, linear inscription of history that abandons what it deems untimely carries less weight here.

At other moments, the organization of Syrian labour is treated critically. In Nights of the Jackal, fluctuations in crop prices ruin the plot’s central family. The Chickens provides a damning exposé of collective farming. Step By Step (Oussama Mohammad, Syria, 1978) proffers further documentary cynicism, interlacing children’s declarations about what they want to be when they grow up (doctors, engineers) with details of how child labour interrupts school, the long working hours non-civil service adults endure (at least ten hours per day) and the sheer numbers who are forced to leave their villages to take up jobs in the military or day-rate construction in order to survive. A May Day speech on the radio saluting workers, so typical across the socialist world, seems hollow in the context of these hardships and specific individuals are implicated when a prominent road-side poster of former President Hafez al-Asad comes into view during a travelling shot.

The literal untimeliness of certain working days, ones that are more arduous than those of the filmmakers, becomes evidence to trigger a rejuvenated struggle for Syrian social rights. However, the filmmakers’ own types of labour also very clearly enter the picture. Compositions are never rough or haphazard in Syrian state cinema; they are frequently the result of precise prior planning that refuses to take the easy filmmaking route. Helicopter shots, crane shots, frames-within-frames that incorporate mirrors, crowd scenes, scenes with animals, precisely choreographed battles, all captured within long takes that are unforgiving of the mistakes that such unpredictable contributors can precipitate.

The end result is a cinema that wears its artistry on its sleeve and thereby highlights the efforts of creative labourers. Viewers are less likely to be swept up in an immersive alternative world, more inclined to involve themselves in wondering how certain dexterous techniques were achieved, something that is less eagerly promoted within the output of those filmmakers across the world employed on seventy-plus hours per week contracts. Narratives also incorporate cultural workers, such as Marwan, the lead character in Under the Ceiling (Nidal al-Debs, Syria, 2005). As a struggling but principled filmmaker, Marwan must weigh up the disadvantages of making a tourist documentary purely for the money while his friend Ahmad, a politically-committed poet, charges to the front to fight in the Lebanese Civil War.

Political decisions about how to expend (artistic) labour time are not, evidently, restricted to the confines of the cinematic text. As has become apparent, the Syrian film industry does not comply with the typical “rationalization” processes of capitalist production, meaning that the movies roll out at an unrushed rate of one and a half per year. As with the government’s treatment of Quneitra, there is a benefit to what might appear to be non-productivity. Quality of employee life cannot be forfeited for output. This model refuses to accept that the tempos and time constraints of most other movie production schedules as somehow “necessary.” Syrian cinema has all the time in the world and, largely because of this, it may well be running out of time, squeezed by the costings of casualized manufacturing.

The decisions Syrian cinema has made consequently demand a recasting of a notion of value: not value for money or what can be garnered from economies of scale amidst lucrative global circulation networks, but the value of not placing employees in painful, even dangerous situations courtesy of unbearably long working hours. By announcing “we make films without any commercial pressure”[22] Mohammad Malas, one of the NFO’s most well-known and recently-arrested directors, exposes the disparity between Syrian working regimens and one of the fundamental principles of capitalism: that objects be created with the primary goal of generating profit. His NFO colleague, the director Nidal al-Debs, corroborates: “Cinema is culture and culture is not supposed to make monetary gain.”[23] To those of us living in a world where films are first and foremost a commodity, the idea that they might exist and circulate under terms other than those of consumerism brings forth alternative ways of thinking about and, perhaps, producing cinema. It raises, for instance, the idea of a film culture that is shared, rather than bought or sold. On a multitude of fronts, then, Syrian cinema compellingly insists that culture can be thought of, and can function, outside and in opposition to the ambits of private property or its supposed utility. As will become clear shortly, this perspective resonates through how these films are made available – or, rather, unavailable.

If Syria’s future is indeed chivvied towards increased marketization, the NFO’s anti-capitalist sentiments will seem as incompatible with local trends as it is with foreign ones. Chances are that the chief argument against the NFO, and other state institutions like it, will be one of cost-efficiency. Evidently, this logic runs completely counter to how the NFO’s staff have been encouraged to define cinema and operate as employees. Yet, even on these terms, it is questionable as to whether a marketization argument would win. Syrian films cost around one million US dollars to make, but look significantly plusher due, largely, to the time spent on them.[24] Most other movie production has so long been inculcated within the tenets of risk management, within a post-Fordist schema that manufactures project-by-project and just-in-time, that it has had to pay out much higher freelance wages, studio and equipment hire fees and insurance. This means filmmaking of an equivalent standard costs significantly more outside Syria than within it.

Ultimately, though, any battle between private enterprise and state sponsorship would be ideological, and probably not won according to the outcomes of such accounting. As post-socialist history confirms, the state-owned film industries of Eastern Europe lost the bulk of their government subsidies, along with the preferential tariffs and international distribution circuits that supported them. In practice, this paved the way for their transferral over into the private sector. Sizeable public assets were sold off, resulting, as was the case in Czechoslovakia/the Czech Republic, in inflated rents for film manufacturing facilities that are now beyond the reach of locals. By capitulating to the sway of competition, Czech movie personnel, expertly trained at government expense, were relegated as cheap labour for foreign runaway productions at the cost of developing their indigenous cinema culture. The narrowing down of employment options when a planned economy is dismantled, all in the name of a supposedly free market, prompts an investigation into just how engineered the replacement schema can be, albeit by profiteers in collaboration with powerful institutions such as the World Bank, IMF and World Trade Organization. At best, co-production becomes an option, as it has been in another socialist country: Cuba. However, the stipulations to pander to a wealthier audience and a more lucrative, expanded market can often derail creative and political aspirations. To date, Syrian state cinema has refused co-production for reasons that a deeply critical Oussama Mohammad (another director on the NFO payroll) lays out:

The National Film Organization regards collaboration with European counterparts as the road map for colonization. The argument goes like this: How could countries that once colonized us, or coveted our riches with colonial designs be attributed good intentions. Europe does not really recognize Israel’s occupation of our territory as a crime, and they have absolved Zionism from the occupation of Palestine, the expulsion of its people from their homes. Europe does not see Zionism as an ideology of terrorism. How can we collaborate hand in hand with countries that defend all these crimes?[25]

For reasons like these, Syria has been reluctant to enter into similar arrangements for the distribution of its movies. While a matrix of spectatorship once existed between various second world and non-aligned nations, this is now drastically diminished, meaning that Syrian films made since the dissolution of these socialist circuits are more likely to air only at the bi-annual Damascus Film Festival, and then never again resurface in a theatre. Nidal al-Debs explains:

The National Film Organization owns the films and does not care to make prints or distribute them. It finds no need for that. Why do it? They will simply be screened at festivals and that will be enough. Syrian cinema makes no profit anyway, so why strike more than one print?[26]

Positioned thus, the movies unequivocally refuse that cornerstone of capitalism: the maximization of profit. The unavailability of the movies reinforces parallel demands, already determined throughout the stages of the films’ production: that we detach from our standard, predictable attributions of value and the reasonings of revenue generation in our understanding of cinema. The oeuvre and its inaccessibility provide a sad object lesson in how impossible circulation can be for movies that are not, primarily, commodified, that do not function hand-in-glove with the oligarchical structuring of global film distribution.

Our gazes can then be redirected from the value of the end product towards its modes of manufacture, which are, perhaps, a more promising site for political action. The dream would be not to immediately judge these movies obsolescent because of their narrow availability, or because they spring from a mini oligarchy all their own. That mission to declare redundancy, after all, is the logic of capital in its ceaseless search for new commodities and, with it, the need to deem others past their sell-by date so they can be replaced. Instead, an interrogation of novelty as a value within marketplace demarcation should be undertaken. Certainly, by bypassing the dominant networks of access in the name of socialism, this material becomes the property of everyone, but no one. Yet it then has the capacity to extend outwards towards broader questions about ownership. A radical mining of history via this rare, untimely outpost of not-for-profit state cinema can surely offer alternatives to prevailing models of intellectual property and commodification. Syrian cinema’s political principles could, for instance, help conceptualize something that is usually considered near-impossible: a film culture that assumes the creative commons model.

Just as the dissemination (or not) of an end film product can act as a craw in the throat of capitalist exploitation, so too can another dimension of Syrian cinema: its ways of working. If capital does its best to obscure the fact that it is a social relation created predominantly through labour and wage differentials, then Syria’s eschewal of profit from movies brings workers’ rights acutely to the fore. In all the discussions of human rights violations in Syria, it has seemed untimely to most commentators to mention certain better conditions to be found there. Yet is this not a deeply ideological resolve? One that rides the chariot of democracy rough-shod over some entirely enviable labour practices, pensions, and securities, perhaps towing, if post-socialist history serves us correctly, a worrisome neoliberal agenda in its wake? For all workers, there is much to be learnt from studying the untimely spectre that is Syrian state cinema, even, in fact expressly because we can barely access these films.

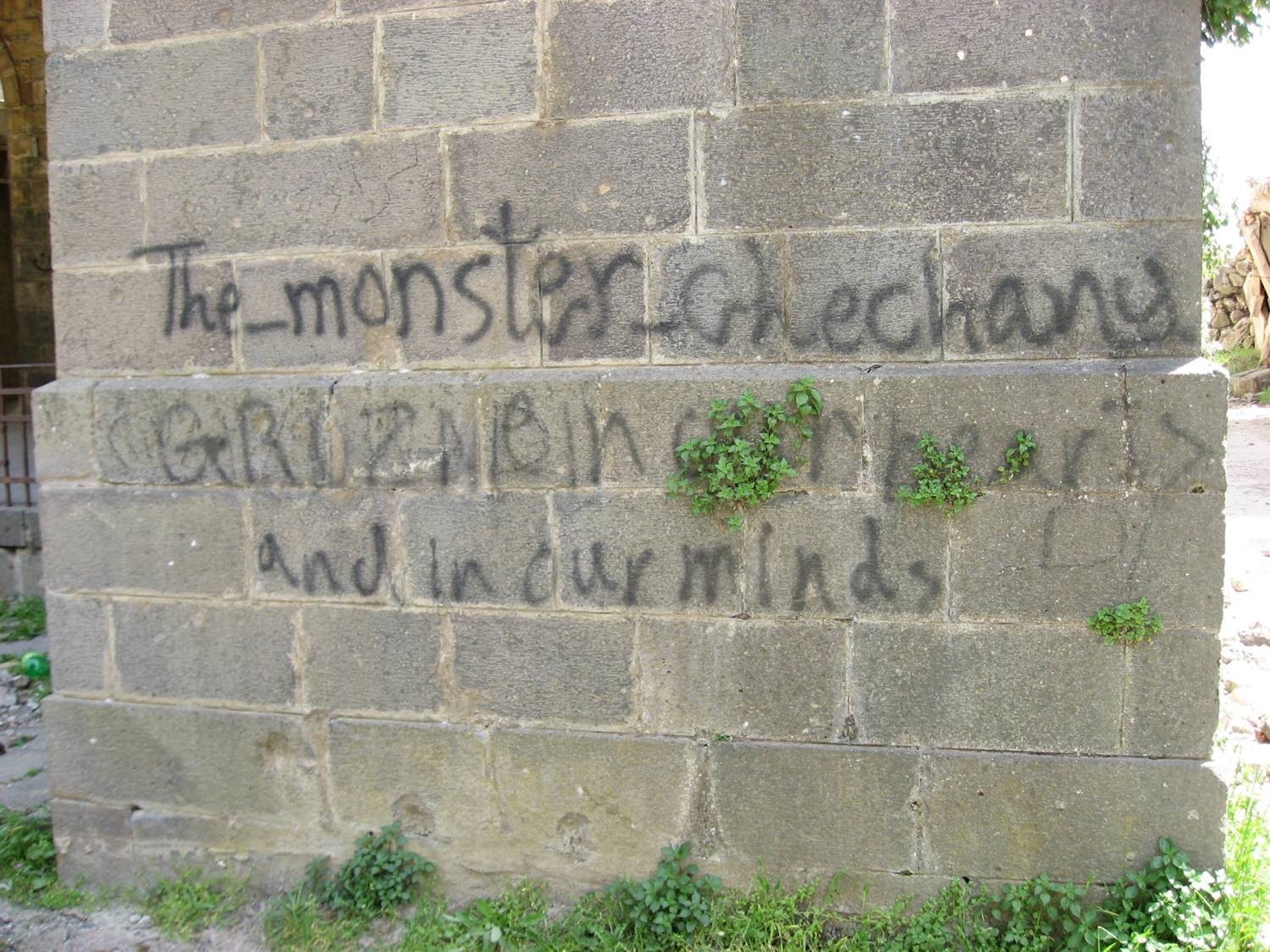

In Quneitra, on the side of a half-destroyed building, probably scrawled by a member of the UN army in a language not quite their own (English), one can read the following graffiti: “The monster Chechny [sic]. Grozne in our hearts and in our minds.”

This emotional declaration acts as an unsanctioned reminder of the potentially catastrophic consequences and repeated aftershocks of a transition out of socialism, a socialism that may have brutally crushed dissent to maintain a questionable type of stability, but whose overthrow offered no simple solutions. History-making, as a discourse with meaningful political impact, perhaps does not want to hear such statements at present – as its present. Syrian cinema’s thematic preoccupations and means of production similarly rankle any easy dismissal of everything a denounced, flailing and defensive socialism stands for within the rhetoric of change in the Middle East. A stubborn insistence upon the dynamic critical relevance of chronologies that are marginal or suspiciously pronounced defunct (even both at once) could well halt something entirely worse replacing them, but without lapsing into the mummification of a stale or forced continuity either.

My thanks to Michael Lawrence for his patience as I tested out embryonic ideas, his suggestions on a later draft, and for weekends that are never actually lost.

WORKS CITED

al-Isfanani, Abu al-Faraj. The Book of Strangers: Mediaeval Arabic Graffiti on the Theme of Nostalgia, trans. Patricia Crone and Shmuel Moreh. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2000.

Al-Jabri, Abed Mohammed. Naqd al’‘aql al’‘Arabi 1: The Construction of Arab Reason Beirut: The Arab Cultural Centre, 1991.

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1969.

Brown, Wendy. Edgework: Critical Essays on Knowledge and Politics. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Caldwell, John Thornton. Production Culture: Industrial Reflexivity and Critical Practice in Film and Television. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Deleuze, Gilles. Negotiations, trans. Martin Joughin. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

Emporiki Bank. “Country Trading Profiles: Syria – Labour Market,” http://www.emporikitrade.com/uk/countries-trading-profiles/syria/labour-market (accessed 22 Dec. 2010).

Gallagher, Nancy. “Interview – The Life and Times of Abdallah Laroui, a Moroccan Intellectual.” The Journal of North African Studies 3 (1998), 132-151.

Grosz, Elizabeth. The Nick of Time: Politics, Evolution and the Untimely. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Holmes, Leslie. Post-Communism: An Introduction. Cambridge: Polity, 1997.

Kuleshov, Lev. Cinema in Revolution. Edited by Luda Schnitzer et al., trans. David Robinson. London: Secker and Warburg, 1973.

Malas, Mohammad. “Between Imaging and Imagining, Women in Film,” Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers. Edited by Rasha Salti. New York: AIC Film Editions/Rattapallax Press, 2006.

Marché du Film. Focus 2009: World Film Market Trends. Cannes: Festival de Cannes, 2009.

Mohammad, Ousamma. “Tea is Coffee, Coffee is Tea: Freedom in a Closed Room,” Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers. Edited by Rasha Salti. New York: AIC Film Editions/Rattapallax Press, 2006.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Untimely Meditations. Edited by Daniel Breazeale, trans. R. J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Øvensen, Geri and Pål Sletten. The Syrian Labour Market: Findings from the 2003 Unemployment Survey, Oslo: FAFO, 2007.

Rancière, Jacques. “Comment and Responses.” Theory and Event 6 no.4 (2003).

Sabry, Tarik. Cultural Encounters in the Arab World. London: IB Tauris, 2010.

Smith, Adrian and John Pickles. “Introduction: Theorising Transition and the Political Economy of Transformation,” in Theorising Transition: The Political Economy of Post-Communist Transformations. Edited by John Pickles and Adrian Smith. London: Routledge, 1998.

Todorova, Maria. “From Utopia to Propaganda and Back.” In Post-Communist Nostalgia, edited by Maria Todorova and Zsuzsa Gille. New York: Berghahn Books, 2010.

Wright, Lawrence. “Disillusioned,” In Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers. Edited by Rasha Salti. New York: AIC Film Editions/Rattapallax Press, 2006.

[1] Khaled Yacoub Oweis, “Crackdown Escalates in Syria, 2 Protesters Killed,” Reuters, July 14, 2011, accessed 20 January 2012, http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/07/14/us-syria-idUSTRE76C65N20110714; “Arab League observers urged to visit jailed bloggers and journalists, demand their release,” International Freedom of Expression Exchange: The Global Network for Free Expression, January 3, 2012, accessed 20 January 2012, http://www.ifex.org/syria/2012/01/03/milan_released/; “Security Crackdown Continues Across Syria,” Al Jazeera, July 2011, accessed 20 January 2012, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2011/07/2011714115151803721.html; Scott Macaulay, “Syrian Filmmaker Nidal Hassan Detained on Way to Cph:Dox,” Filmmaker: The Magazine of Independent Film, November 2011, accessed 20 January 2012, http://www.filmmakermagazine.com/news/2011/11/syrian-filmmaker-nidal-hassan-detained-on-way-to-cphdox/.

[2] As cited in Abu al-Faraj al-Isfanani, The Book of Strangers: Mediaeval Arabic Graffiti on the Theme of Nostalgia, trans. Patricia Crone and Shmuel Moreh (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2000), 34.

[3] See Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, ed. Daniel Breazeale, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997) and Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” trans. Harry Zohn, in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 253-264.

[4] Wendy Brown, Edgework: Critical Essays on Knowledge and Politics (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005), 4.

[5] “A Call From Syrian Filmmakers to Filmmakers Everywhere,” Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/notes/syrian-filmmakers-call/a-call-from-syrian-filmmakers-to-filmmakers-everywhere-%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%B3%D9%8A%D9%86%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86/126777020733985 (accessed 25 July, 2011).

[6] See the lengthy and articulate argument that outlines this issue in Ousamma Mohammad, “Tea is Coffee, Coffee is Tea: Freedom in a Closed Room,” Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers, ed. Rasha Salti (New York: AIC Film Editions/Rattapallax Press, 2006), 152-3.

[7] Abed Mohammed Al-Jabri, Naqd al’‘aql al’‘Arabi 1: The Construction of Arab Reason (Beirut: The Arab Cultural Centre, 1991), 47, quoted in and translated by Tarik Sabry, Cultural Encounters in the Arab World (London: IB Tauris, 2010), 161-2.

[8] Nancy Gallagher, “Interview – The Life and Times of Abdallah Laroui, a Moroccan Intellectual,” The Journal of North African Studies 3, no. 1 (1998): 143.

[9] Elizabeth Grosz, The Nick of Time: Politics, Evolution and the Untimely (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 117.

[10] Mohammad Malas, “Between Imaging and Imagining, Women in Film,” Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers, ed. Rasha Salti (New York: AIC Film Editions/Rattapallax Press, 2006), 119.

[11] Lev Kuleshov, “The Origins of Montage,” Cinema in Revolution, eds. Luda Schnitzer et al., trans. David Robinson. (London: Secker and Warburg, 1973), 68.

[12] Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations, trans. Martin Joughin (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 170-71.

[13] Jacques Rancière, “Comment and Responses,” Theory and Event 6, no. 4 (2003).

[14] Geri Øvensen and Pål Sletten, The Syrian Labour Market: Findings from the 2003 Unemployment Survey (Oslo: FAFO, 2007), 30-1.

[15] Emporiki Bank, “Country Trading Profiles: Syria – Labour Market,” http://www.emporikitrade.com/uk/countries-trading-profiles/syria/labour-market (accessed 22 Dec. 2010).

[16] Lawrence Wright, “Disillusioned,” Insights into Syrian Cinema: Essays and Conversations with Contemporary Filmmakers, ed. Rasha Salti (New York: AIC Film Editions/Rattapallax Press, 2006), 46.

[17] A common observation recapitulated in Leslie Holmes, Post-Communism: An Introduction (Cambridge: Polity, 1997), 208.

[18] Adrian Smith and John Pickles, “Introduction: Theorising Transition and the Political Economy of Transformation,” in Theorising Transition: The Political Economy of Post-Communist Transformations, eds. John Pickles and Adrian Smith (London: Routledge, 1998), 7.

[19] John Thornton Caldwell, Production Culture: Industrial Reflexivity and Critical Practice in Film and Television (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 44.

[20] Caldwell, 80

[21] Maria Todorova, “From Utopia to Propaganda and Back,” in Post-Communist Nostalgia, eds. Maria Todorova and Zsuzsa Gille (New York: Berghahn Books, 2010), 7.

[22] Mohammad Malas, interview with author, 16 Dec. 2009

[23] Nidal al-Debs, interview with author, 17 Apr 2010.

[24] Marché du Film, Focus 2009: World Film Market Trends (Cannes: Festival de Cannes, 2009), 67.

[25] Mohammad, 157.

[26] al-Debs.