Introduction

The actors in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Canterbury Tales (I racconti di Canterbury [1970]) are English and Italian. The film has an English and an Italian version, both dubbed. The speech of the characters in the two versions is ‘popular’, the speech of ordinary people.

Almost certainly Chaucer’s poem in Middle English went through a series of transformations for the different language versions of the Pasolini film. Middle English was modernised into everyday English in turn translated into Italian. The Italian was then retranslated into Italian common speech and slang, much of it Neapolitan, while the English dubbed version, a long way now from Chaucerian Middle English, became colloquial English ‘modern’ speech and slang, that is ‘like’ Chaucerian English but not Chaucerian English. The similarity between the two linguistic versions and their differences are simultaneously present as the precondition for a comparison between languages and the historical and social differences and above all linguistic-poetic differences that unite and oppose them.

The linguistic shifts between languages made one language the likeness of another without each losing their otherness. Thus, modern colloquial English speech in the Pasolini film functions as a comparative to 14th century Middle English, at once different and an equivalence. The same is true with the Italian in its relation to the English. In either case the linguistic analogies refer to an earlier time, to Renaissance England or to Italy before, according to Pasolini, language in Italy had been homogenised first under Fascism and then with post-war consumerism into a bureaucratic unified Italian from the late 1920s.

The film ‘goes back’ to the 14th century while remaining nevertheless in the present. Neither the one time nor the other is effaced. There is no make-believe in the Pasolini film as in most historical film spectacles set in the past and sustained in the present by the illusion of the past in which the present is temporarily negated for the sake of the believability of the film. Pasolini turns a make-believe ‘reality’, reality in the usual sense, into a linguistic play of comparatives, of analogy and metaphor between languages and times, both made evident.

Prologue

The Canterbury Tales was written by Geoffrey Chaucer toward the end of the 14th Century. The Tales are told by pilgrims walking from Southwark near London to the shrine of Thomas Beckett at Canterbury Cathedral. The telling of the tales is a contest between characters for the best tale told. The tales and the telling are entertainments to pass the time. There are two narrators: Chaucer who presents the tales of the pilgrims in a Prologue and the pilgrims who recount their tales. Chaucer’s Prologue frames the various narratives that follow. The narratives, predominantly written in verse, are Chaucer’s, though Chaucer pretends otherwise as if they are documents of the ‘people’ that he has recorded. His fiction is that the pilgrims are narrators of the tales rather than that is he who ‘impersonates’ them, a Chaucer in disguise, a likeness. Such an act of duplication and its deceit marks Pasolini’s Canterbury film as well and perhaps all his films.

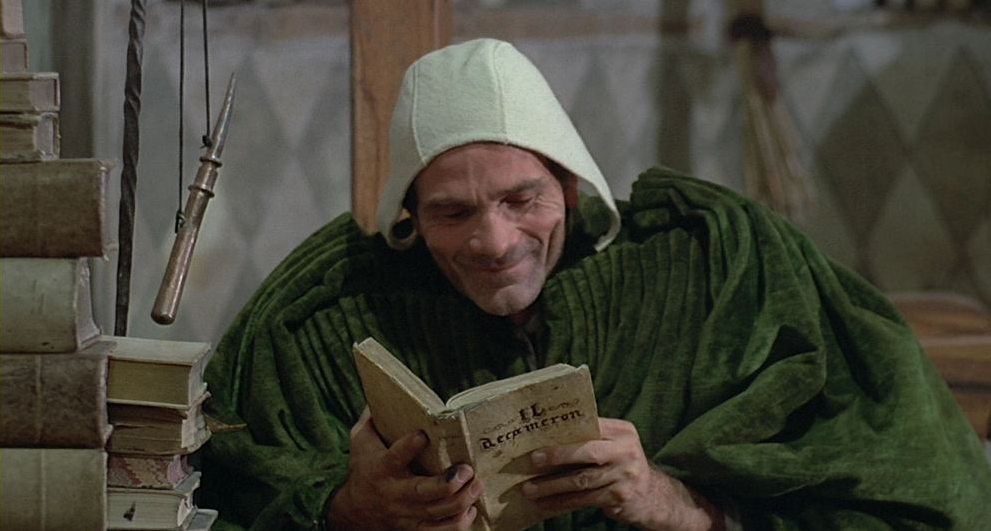

Chaucer and his tales are cited, rather than represented, which is equally the case in Pasolini’s films that cite myth: Edipo re (1967), Medea (1970), Porcile (1969), Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (1964), (which Pasolini noted was his film closest to Il Decameron [1970]). Il fiore delle mille e una notte (1974) set in a mythical Arabia is a series of mythical tales whose structure is similar to the other two films in the Trilogia di vita, and, as he himself said, to Il Vangelo.

Chaucer’s (and Pasolini’s) fiction of multiple voices and languages create analogies between the tales and between the authors. Each tale, though different, is, in its form, like another tale, a play of comparatives between similar structures and mirrored, serial contents.

The form of the Chaucer is duplicated in Pasolini’s film where Pasolini ‘plays’ Chaucer, pretends, like Chaucer pretends, to speak and inhabit other voices and other characters. Pasolini’s film goes further since Pasolini assumes the role of Chaucer and the roles of the various pilgrims. In both cases, in language, in dress and in gesture, the works are masquerades, everything and everyone disguised, including the authors who are not what they pretend to be.

The Chaucer has twenty-four tales, the Pasolini, eight: the Merchant tale, the Friar’s, the Miller’s, the Wife of Bath’s, the Reeve’s, the Pardoner’s, the Summoner’s.

Cinema and Film

Pasolini’s The Canterbury Tales/I racconti de Canterbury is a pastiche of elements from Renaissance and Mannerist paintings, fourteenth century literature, dialect, languages, popular and classical music, some of it Italian, some English, some German, but not of films. The film is a film, but the cinema has no cinematic reference, no presence.

French Films of the Nouvelle Vague, especially the films of Jean-Luc Godard are filled with citations to other films and overwhelmingly to American films of the 1950s and 1960s. The cinéphilie of the Nouvelle Vague was a love of American cinema, the films of Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, Vincente Minnelli, Nicholas Ray, Anthony Mann, Ernst Lubitsch, Otto Preminger, Raoul Walsh, Richard Brooks, Elia Kazan, Sam Fuller, of Westerns, gangster films, melodramas, musical comedies, war films, the genres that typify Hollywood cinema. The historical ‘cinematographic’ presence of references to American films in French films (true still today) was true critically as well. The essential focus of French films and French criticism at least to the mid 1970s remained the American cinema.

The ‘school’ of film attended by Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol and others was the front row of the French Cinémathèque whose director and Nouvelle Vague hero was Henri Langlois, who had not only introduced them to the world of cinema, but sustained it and nurtured it. The Cahiers du cinéma was devoted to American ‘auteurs’, whom the journal interviewed, promoted and whose interviews it published over the years from the late 1950s. American films and filmmakers were central to the politique des auteurs of Cahiers du cinéma, its enthusiasm for the cinema and its idea of the cinema, that included a rejection of a literary, uncinematic French cinema, what it called, “a cinema of quality”. The importance of the American cinema was not only crucial to the French cinema, also to European film culture of the period and to film modernism.

There is little or no trace of an American presence in Pasolini’s work, neither in his films, nor his criticism, indeed, there is little presence of the cinema at all, except perhaps for the films of Charlie Chaplin whom he admired. Pasolini disliked American films (he loathed Hitchcock and Hawks, for example, for their make-believe, their continuity editing, their linear narratives, had no apparent interest in the ‘new’ American cinema of Ray and Mann) and seldom referred to other films, American or otherwise, in his writings, nor did he take other films as his models. Pasolini’s citations in his films, his references are essentially pictorial from Medieval, Baroque and Mannerist paintings: from Giotto, Cimabue, Masaccio, Piero Della Francesca, Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino, Caravaggio or are citations of myth and fairy tales. It is these elements that his films from the first to the last exemplified. When he wrote about the cinema, his writing tended to be ‘theoretical’, for example his 1960s essays on semiotics and film signs or his poetic-philosophical discourse on the shot sequence and his overly dense and overworked notions of reality. His theoretical writings can be opaque and confusing and their value as ‘theory’ questionable. They illuminate Pasolini’s work and thought, but less so, if at all, do they illuminate the cinema. Specific films as films, as style or as structure, were seldom referred to and individual filmmakers or films hardly figured in his ‘theory’ which tended toward abstraction.

Consecration, Sacredness, The Fetish

The images of paintings Pasolini cites are citations of their forms. They are shot frontally, in close up, in counter point to other images, like rhymes, close-up to close-up, movement in one direction to movement in reverse, shots and sequences organised symmetrically. The shot isolates the image, each shot a register not so much of a reality than of an ideal reality cut out and marked, consecrated, at once sacred and mythical as in an altar piece … or a fetish. Salò is perhaps Pasolini’s most evident filmed fetishism, though the image as fetish and myth is the dominant feature even of his earliest films.

The close up and the cutting out, the rejection of continuity by Pasolini, has a double yield or consequence.

One, is a reversal. What is cut out and consecrated may be like the high art of the early Renaissance in its forms, but in its subjects or contents are something else entirely. The juxtaposition of form and subject create a comparison and associations between what are scandalous or grotesque or dirty or blasphemous: the form of a Masaccio painting, for example, with a subject of low life, whores, pimps, criminals, murderers, sadists, are framed like saints, are sanctified. The reversal is crucial to all of Pasolini’s work, to its shock and outrage and power. The sacred and profane trade places as comparisons and oppositions, turned, as in Carnevale, upside down, the low worshipped, the high defiled.

The other yield that relates to the cutting out of images, is when images become like figures of speech, pure form, pure utterance, an object without continuity, without a narrative, only itself, elements that can be rhymed, associated, made into metaphors, made objects of adoration, figures of language, the material for making poetry.

Linguistic Fictions

The mix of characters is a mix not only of languages, but of skills, themes, points of view, comportment. Language is always a form. Its other aspects, for Pasolini, including physical ones and tonalities and gesture become language too. For Pasolini, they ‘speak’.

The Tales are as diverse as the characters who recount them. The two crucial voices are that of the one who frames (Chaucer) and those who are framed (the pilgrims), a single voice governing multiple ones. Some voices are in verse, others in prose. The collection of tales is a collection then of differences held together in a unity of time, place and intention by the fiction of a pilgrimage.

The pattern is the same in Pasolini’s I racconti though set off by further differences, not only Pasolini to Chaucer, but Italian to Middle English, and an Italian often in dialect, and, as with Chaucer, a language of everyday. In this respect, the difference, verse to prose in Chaucer, rhymes with the difference standard Italian to dialect Italian in the Pasolini. There are further rhymes between the two works of the physical (appearance) to the spiritual (character), the common to the High, the vulgar to the sacred, parody to the serious.

The Middle English of Chaucer is notable for its use of dialectal forms. There is a profusion of characters and tales, languages, linguistic differences that accumulate and spiral. These differences encourage comparisons: between works, languages, societies, past and present, customs, class, Italy and Medieval England, the body and the spirit.

—

Pasolini was born and educated in Bologna in Central Italy. During the war, he, with his mother, lived in Casarsa, in the Italian countryside of Friuli at the extreme North East of Italy where Pasolini taught school. What was spoken in Casarsa, besides Italian, was Friulian, the local language. Pasolini loved Friuli and its language. He studied it and adopted it and partly was responsible for reviving and preserving it. He adopted not only the language, but the place and also its people. It was as if the sophisticated, highly educated Italian, a student of the Fine Arts, was in masquerade in Friuli playing a rural figure, not what he was but what he would have liked to have been. And what he would have liked to have been, his fiction, is what he fundamentally became and at heart and by sympathy what he was, at once himself and other than himself, as if possessed by that ‘other’ as more real, his dream a reality.

From 1942 to 1953, Pasolini’s first books of poetry were in Friulian not Italian, more precisely, they were translations from Italian into Friulian. The poems were first written in Italian, then translated by Pasolini into Friulian. In the published editions, Italian is present at the bottom of each page, as a footnoted ‘translation’ from Friulian, the opposite of what actually occurred: the translation was Friulian from Italian but made to seem as if it was the reverse. And Pasolini, like the translation, in disguise.

Friulian was not Pasolini’s language, but the language of an ‘other’, the peasantry, his mother, which Pasolini brought in or brought back by a complex exercise of translation and identification, a miming by which Pasolini, as in his I racconti di Canterbury, fictionally assumed another identity and another language, each doubled whose origins were made obscure by a borrowed, adopted persona.

The ‘other’, Friuli and Friulian, was for Pasolini an idealised peasant society, mythical even, pure, innocent, as yet uncorrupted by modernity, belonging to the past but doomed by the modern to disappear. To adopt its language, its accents, was to identify with an ideal and its threatened loss.

Soon after, in the early 1950s, Pasolini was forced to flee Friuli for Rome, once again with his beloved mother. He had been accused of sexually molesting young boys, and, he was, and perhaps even worse, a Communist, a double outrage, sexual and political. The flight from Casarsa for him was like an expulsion from the Garden of Eden, or so he imagined it to be.

In Rome, Pasolini found another Paradise among the sub-proletariat of the Roman slums. They became, as Friuli and Friulian had been, a social, poetic and linguistic model, but this time, it consisted of a different ‘other’, not the bucolic, but the reviled and the marginalised of the Roman slums: thieves, whores, pimps, slobs, cheats, criminals, those for whom work was, if not a curse to be avoided, a sign of belonging to a society they had rejected or had rejected them, a rejection romanticised by Pasolini as a purity of the refusal to conform, even thereby a sacredness.

The sub-proletariat Roman slang was uttered not simply by their tongues, but by their bodies and gestures, their being. If, from an established social perspective those of the Roman borgate might be thought of as degenerate or vile or worse, from Pasolini’s perspective they had the virtue of being genuine and that virtue, their rejection and refusal of what conformed to social norms, made the vile something positive to him, even noble.

Pasolini learned his Roman with the help of Federico Fellini and which Pasolini adopted as he had learned and adopted Friulian. Roman dialect is present in Fellini’s 1957 film Le notti di Cabiria on which Pasolini was involved.

Roman and Friulian were, for Pasolini, ancient languages, a survival from the past. The Roman borgate was for Pasolini a Paradise, albeit shabby. More romantically still it was Paradise Lost, a remnant and, like its inhabitants, in rags, and like Roman and Friulian, threatened with extinction by modernisation. This set up a series of reversals for Pasolini whereby the ancient had more value than the modern and the despised was more sacred than the Sacred. All that society said was good, he rejected , and all it rejected Pasolini embraced.

Modern Italy and Italian was for him not only the reverse of difference, but a threat to it and thus a threat to language and to poetry, to ‘life’, for Pasolini, a danger not simply to be avoided, but challenged, attacked.

Translations

Traditional films have tended to hide the film behind an illusion that what is represented is real. For the illusion to be convincing, a series of dramatic and stylistic mechanisms are set in motion to eliminate anything other than the fiction, as if there is no contrary to it, no other reality, but itself. The essential relation is between what is represented—the subject, the ‘content’—and the representing of it—‘form’, languages.

That the dimension of the representing, may become evident and noticeable, ‘starred’ and emphatic, highlighted in order to be attended to, noticed and recognised, risks causing a break in the unity of what is represented, disturbing the illusion, hence a threat to its maintenance and of a certain kind of fiction and fictional writing, of verisimilitude, and of the coherence they depend upon for their effects.

Pasolini’s stress on language in its variety and multiplicity and that included the particularity and uniqueness of poetry, plays upon incomprehensibility, even the opaque, what is alien, restricted, marginal, antique, nonsensical, sometimes scandalous, obscene and outrageous, in any case, what is incomplete and unresolved and traditionally unacceptable. Its purity and presence as language, for Pasolini, rather than as representation, is a process rather than a finality. It calls language itself into question: “What is this for? “What does it mean?” “What is going on?”, “Where is it leading to?”, without providing answers. It resists a resolution or harmony or agreement that might efface representing and language by becoming invisible and instrumentalised with only the represented, one-sided, intact, present and irrefutable.

One way of understanding the importance for Pasolini of the plurality of languages and reality and their differences and range is by the ubiquity of translations in his work whereby one thing is translated into another and in such a way that both survive, openly make-believe, a possession, a ventriloquism, an ‘act’, theatre (often of the absurd).

Every Pasolini film is based on a literary text, like I racconti di Canterbury is based on The Canterbury Tales. The shift—translation is always a shift—from one language to another, one medium to another, one practice to another, is not for Pasolini adaptation where one term disappears to become an other term, but rather a comparison between elements simultaneously like and not like, that move ‘between’, where what is crucial is not one thing nor the other, but a relation, like the copresence of Friulian and Italian, Neapolitan and Middle English, Roman slang and literary Italian, street kids and Renaissance art.

Translation can be generalised beyond the movement of one language displacing another. The displacement may involve prose to poetry, writing to film, reality to fiction, words to gestures, the past to the present, the abstract to the physically concrete, that is, as some kind of transposition between forms and genres. One of Pasolini’s most interesting essays relating to the cinema—written in 1965—is entitled La sceneggiatura come “struttura che vuol essere altra struttura” (The screenplay as “a structure that seeks to be another structure”). The title could be applied to most if not all of Pasolini’s work, and to the conduct of his life, where ‘another’ is a quest, a shifter and a value and where context and language meet and redefine each other. With Pasolini, there is always a distance between terms and practices made evident and once made evident set into play, a precondition for comparatives, for metaphor.

Rhymes

Each of the Tales of Chaucer or those ‘translated’ and ‘transposed’ into Pasolini’s I racconti have repetitive themes which are essentially similar. Each tale is like another. Each involves desires that require some kind of duplicity, betrayal, dishonesty, deceit to be satisfied and realised, hence their comedy. Such themes belong to what the tales in their various languages and various contents represent. Because the contents are repeated they function as rhymes. Each tale is a return, and each a variation, likenesses proliferate as comparisons.

Two translations are at work in I racconti. The first involves a content becoming a form, becoming language, by the fact of repetition and rhyme such that each turn and scene in the film, each tale because repeated without being identical is a form, for example, duplicity in its various guises (dishonesty, trickery, secretiveness, false identity) which is always a comparative. The ‘content’ of the film then necessarily gives birth to form (comparatives, oppositions, repetitions, negations, metaphor, variation, rhyme, exaggeration, parody, masquerade). The second is the conversion of the form to a content. What else are these processes, what else could they be but forms pretending to be a content? And what else is its content but its form?

Such double reversals are like his translations: Italian to Friulian, Friulian back to Italian, each the other and both related.

Chaplin

One of Pasolini’s models is Chaplin, cited in Pasolini’s ‘comedies’ with Totò and Ninetto Davoli, both like puppets, and also La ricotta (1963): Uccellacci e uccellini (1966), Che cosa sono le nuvole? (1967), La terra vista dalla luna (1967) and La sequenza del fior di carta (1969). There is Pasolini’s brief essay of 1971: La “gag” in Chaplin.

In Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), Chaplin is Henkel and Henkel is Hitler and both are Chaplin, the Jewish barber, and the Jewish barber is all the Jews. These are relations of resemblance, of similitude. One of the great scenes of the film is when, at the end, the three characters threaten to meet and unravel the masquerade and deceit on which the film depends: Henkel, a citation of Hitler, the Jewish barber (who suffered amnesia), and Chaplin himself who is never not Chaplin, anymore than Charlie is never not Chaplin, or Pasolini never not Pasolini no matter what role he plays, or Orson Welles in La ricotta or in Welles’ own films never not Welles, made explicit in Welles’ F for Fake (1974) and Mr Arkadin (1955). The impersonations are self-evident, like circus masquerade and are satires and parodies not only internally, but of reality itself, which is permanently called into question, burlesqued.

The Chaplin film, The Great Dictator, is composed of layers of parallel doubles and duplicities, of likenesses that overlap and in overlapping disturb. The film is a riot of impersonations and metaphors.

Henkel is not Henkel yet he is. Hitler is not Hitler and yet he is. Henkel is not Hitler and yet he is. The same is true for Monsieur Verdoux (1947) and true for all of Chaplin. He is Charlie (the character) and Chaplin (the person) all at once. His films move within a space of comparatives where each resemblance is revealed as a difference.

In Pasolini’s first film, Accattone (1961, the title character is a pimp, a sneak, who betrays his friends and exploits his women. He does no work. The shots of him in the film, frontal as they are in I racconti is a framing derived from the Italian paintings of the Renaissance. In this case, Accattone, the sordid, is likened in images after paintings, to be saintly, and when he is at his worst, made sacred and revered. The mix and contrast of identities and of costume, rags and riches, duplicates the images of Charlie, dignity in rags, and also his character, a deceitful (and comic) honesty, mean and sentimental. Accattone as Chaplin?

The Cook’s Tale in I racconti with Ninetto Davoli is filled by Chaplin’s presence. Chaplin is everywhere cited in the film: in the gag of the eggs, the slide into the river (twice), the soup kitchen scene, the dance sequence (as in Uccelllacci uccellini [1966]), the chase, the policemen like Keystone cops, and by the clothes Davoli wears (the hat, the cane, the trousers a bit dishevelled come from Chaplin’s wardrobe), and the doubling it contains of elegance and tattiness, respectability shredded, yet ridiculously, pathetically maintained.

Chaplin’s films are parodies that depend on doublings of similarities as oppositions. Parody is based on comparatives. In the persons of Davoli and in Totò, Pasolini found his Charlie, a Chaplin who is critical in his being and in his gestures and in all his comedies of society and its hypocrisies, an assault against a single-minded, unified, established world without difference. What is established, what conforms, the respectable for Chaplin (and Pasolini) is not quite human or livable in. The attraction of Chaplin is that he lives differently as if out of the world.

Chaplin’s films, their essence and the essence of his character Charlie, are constructed around the double, where whatever is, is seldom what it appears to be or could be (for example, a cake as a hat, a hat as a cake, infinite translation and unending, riotous metamorphosis), as if the only acceptable attitude is founded on opposition, refusal as a precondition for any change. Reality is a state of mind that can be refashioned, thought differently, not immutable, and therefore easily reimagined and transformed. The delight of Chaplin’s work depends on this possibility of difference, no matter what.

The presence of Chaplin in Pasolini’s films and especially perhaps in films like I racconti di Canterbury and the two other Pasolini films of La trilogia di vita, is not exceptional. Chaplin, I believe, was the only filmmaker to be cited and present in virtually every Pasolini film and to whom Pasolini paid homage, a citation indeed, a medal of distinction, of high art in low wrappings.

In the end, life in America for Chaplin became untenable. He was, for the Americans, dangerous, a subversive, a scandal in their midst, like Pasolini, better elsewhere.

Montage

Traditional montage is linear and consequential, linking differences to create a logic of continuity as its instrument for erasing the evidence of representing, the form of things, what in France is referred to as mise en scène, for the sake of the ‘reality’ of the representation. D.W. Griffith was the master of such editing, the father of the narrative cinema and of its industry, Hollywood.

Eisenstein created another kind of montage, hence another kind of cinema, that of ‘attractions’, collision, contradiction and of distant associations where language is asserted as a declarative presence not to be buried beneath the thick weight of representation. In Eisenstein’s cinema every shot, sequence, scene is noticeable by a gap that is never completely ‘filled’. If Griffith’s cinema brings everything together, concludes in a resolution, the cinema of Eisenstein takes apart by dissolution, inconclusion. One depends on harmony and integration, what it makes believe, its ‘fiction’, the other relies on dissonance and transgression, its ‘truth’, a denial of make-believe.

The Soviet avant-garde of the 1920s valued a comic and popular tradition derived from the circus, popular entertainment, music hall, vaudeville, burlesque, the Café concert and above all, perhaps, from the slapstick of early American films that privileged the ‘gag’, the blow, the kick in the arse, rather than drama, story, development, logic, motivation, character, psychology, reality. It was a way of thinking that was usually destructive leading to chaos, an out-of-control subversion and always exaggeration: the comedies of Mack Sennett, Hal Roach, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Fatty Arbuckle, Buster Keaton and later, of Jerry Lewis, naive, idiotic, and in the present, the disturbing ‘comedies’ of Pier Paolo Pasolini, so shocking and outrageous.

Slapstick directly comes from 16th century Italian theatre, the commedia dell’arte, a theatre of masquerade, acrobatics, caricature, distortion, perpetual movement, sudden reversals, surprise, shock. The commedia was made with stock characters who are ridiculous, sad and lyrical like clowns are. The commedia dell’arte is a theatre of provocation, a refusal of the established, a revolt against the ordinary, a defiance that is essentially visual and gestural, illogical rather than reasonable, physical rather than verbal. Jean Renoir reproduced aspects of commedia dell’arte in his The Golden Coach (Le Carrosse d’or, 1953).

All of Pasolini’s films and especially his later ones including, I racconti di Canterbury, are indebted to these traditions. One way of understanding his I racconti (and also, I think, provocatively, the Grand Guignol terror of his Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma [1975]) is as burlesque theatre.

A direct line is evident that links together the cinema of Pasolini, the theatre of commedia dell’arte, Eisenstein’s theatre and films, Renoir, early American silent comedy, and the burlesque where ‘the body’ and facial expressions and movement displace the interiorisation of drama in conventional theatre. This new and disruptive theatre, so evident in Pasolini’s films, is one of spectacle, surface, gesture, violence, mischief, exaggeration, trickery and physical delight. It is connected to magic and is ‘magical’.

Eisenstein directly invokes this theatre in his “montage of attractions”, attractions, as in circus attractions, as in the fairground, essentially gags or ‘numbers’ (as in variety theatre) in bizarre costumes, an appeal of shock, clashes, eccentricity, governed not by sense, nor linear logic, nor consequence, instead by inconsistency, mockery, satire, discord, theatre against ‘the theatre’, acts at odds with each other, literally, a revolution.

Eisenstein’s Strike (1925) is a perfect example of this aesthetic undermining and overturning, as are scenes in his The Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928). In such theatre and in the films that developed from it, acting and character do not coalesce, acting is not an expression of psychology or drama, nor of ‘reality’, but a defiance, an anti-(bourgeois) theatre that constructs by dismantling.

The immediate context for Eisenstein’s “montage of attractions” was the Soviet theatre of FEKS (The Factory of the Eccentric Actor) founded in the Soviet Union just after the Revolution in 1922 and devoted to the Revolution. The theatre of FEKS was like Commedia dell’arte, like silent comedy, and like, I believe, Pasolini’s late films, such as I racconti di Canterbury. FEKS, in turn, was indebted to the Constructivism of Vsevolod Meyerhold’s theatre and to Vladimir Mayakovsky’s futurism, in short to the avant-garde. Surrealism, Dada and the films of Luis Buñuel in their turn owe an enormous debt to Soviet Modernism as Pasolini owes them a debt, and especially perhaps above all to Buñuel.

Despite all the writings, and they are voluminous, by Pasolini and about Pasolini, there is little reference to the fact that his work is an outstanding example of artistic Modernism. Perhaps the silence is due to his fierce dislike and rejection of Modern society. As with all Pasolini’s films his Modernism is centred on a return of a Past, largely mythical and literary, for example, his I racconti di Canterbury. La trilogia di vita in particular, by its citations of Chaucer, Boccaccio and the Arabian Nights are citations of the early Renaissance, of an art and language and culture at the borders of the coming of the modern world. His is a view of a world and society he adored and that was, in its becoming, about to be effaced by what he loathed and whose loss he lamented. I racconti di Canterbury is that lament.

Clowning

I racconti di Canterbury is an extreme instance of clowning, the circus, slapstick, the physical, of burlesque, Grand Guignol (the Theatre of the Big Puppet). Ninetto Davoli, who ‘plays’ in I racconti and in other Pasolini films, is, like, Totò, a Clown and a Puppet. He sings, dances, plays pranks, seldom speaks (like Harpo Marx whom he resembles) is ridiculous, silly, naive, absurd, an idiot, the opposite of a hero. Pasolini, as Chaucer, is also a clown, though neither he nor Davoli are thereby necessarily funny as clowns are often not funny. They can outrage everything even including comedy because their exaggerations can be cruel and sadistic, even brutal, terrifyingly absurd.

Fellini’s La Strada is a perfect example of such clowning, where the clash between Zampano and Il Matto ends in a terrible death, a prank gone wrong (the same is true in Il Bidone [195x]). The entire film, like other Fellini films, derives from the circus.

What could be more outrageous and less amusing than Pasolini’s Salò, a film of torture, sexual abuse, sadism, shit-eating, pissing in the face, rape, a contest for the most sublime arse, no faces, no persons evident, only bottoms, lined up, on display, sodomy and, finally murder. Yet, nevertheless, I believe, the most productive way of regarding that film and perhaps all of Pasolini’s films, is as an example of the burlesque. Salò is not funny, but then neither is much of slapstick. The scenes in I racconti are refusals, revolt, rejection. If commedia dell’arte is a kick in the arse to conventional theatre, Pasolini’s Salò and his I racconti di Canterbury are equally that, and more radically so perhaps.

Bodies

I racconti di Canterbury can be thought of as ethnogaphy and Pasolini as a social anthropologist recording the customs of a newly discovered outlandish people, obscure, unique, unknown, the Pasolini tribe. His film is crowded with persons, each different by social class, by appearance, gesture, speech, comportment and bizarre customs seldom ever seen before. And, though these ‘persons’ are ‘characters’, the reality of their person is never absorbed by the fictional roles that they play. The best of such ‘primitivism’ is its ritualised behaviour. It seems that all persons in the film are in disguise, in crazy costume, describing grotesque movements. It is disguise, however, that reveals what is beneath the mask.

Character and person then are not unities but differences to each other and differences as comparatives. It is not unlike Jean Rouch’s 1956 Les Maîtres fous, the recording of a possession ritual in Ghana, in West Africa, where the participants become what they are not (because they are ‘possessed): they slaughter a dog, put it up to boil and eat the flesh. They drool, foam at the mouth, moan, shout, parade stiffly like puppets, not quite human. The fiction, central to possession, brings them face to face with their hidden self, an ‘other’ identity. They are what they are not (their true self) and they are not what they are (a false self, imposed and socially dictated).

Not only is there an abundance, an overflow, a teeming of person-actors in the Pasolini film, but the differences between them have less to do (indeed have little to do) with their acting, yet everything to do (or nearly so) with their persons. It is bodies that principally ‘act’ in I racconti. The actions privileged by Pasolini are ‘natural’, in the sense that rather than being dictated by social conventions, social control, they violate conventions, are out of control, not exactly improvisations, but a spontaneity: farting, burping, side-splitting laughter, smiling, sneering, sleeping, dreaming, being silent, erections, gesticulating, dancing, nudity, fighting, mutilation, pissing, shiting, massacring (the ‘sacred’ Il Vangelo secondo Matteo of “the massacre of the innocents” from the Gospels is eerily similar to the torture and slaughter of young people at the close of Salò), the one scene, the one film mirrored in the other.

It is in these respects, in the assertion of the natural that the Pasolini film, and all his films perhaps, reveal their origins in silent slapstick comedy. Visual revolt and revulsion and provocation are not simply matters of the obscene, the lewd, the lascivious, the brutal and the vulgar and forbidden, but part of a more general refusal and provocation in which the natural is posed against false realities, the absurd against the normal, in film and in life, as if it is reality that is coded, denaturalised, conventionalised such that the real becomes the unreal while only the natural, the bodily, the irresistible, the uncontainable and the ungovernable, the unreal made real is the only reality.

‘Reality’, real reality, in Pasolini’s work is always elsewhere, always other, just beyond reach, unattainable, the object of a quest whose means is his poetry, essays, novels and films. There is no end to such quests, no closure. It is bound by a joyous perpetual disillusion, anger and disappointment, a delight in the despised, a cultivation of the shocking. It belongs to the Pasolini production machine whose poetics thrive on what is lost, on the impossible, the negative and the unforgivable.

Pasolini’s actors-characters in I racconti and perhaps, most disturbingly in Salò, engage either in obscene acts or violent and vicious ones, or both together, for example, in The Friar’s Tale in I racconti, where the character played by Franco Citti spies on homosexuals making love then denounces them to the Church authorities. The homosexuals are visited by the Church police and blackmailed: homosexuality is a crime and for Pasolini, the crime is a delight. The real culprits are not the homosexuals, the depraved, but the Church, Holiness. Citti gets his cut of the blackmail loot then watches the condemned receive their ‘just’ punishment.

There are two homosexuals accused in the film, one rich, one poor. The poor one, unable to pay the money demanded by the Church, pays with his life. He is burned alive in religious pomp and ceremony, ‘barbecued’: “You are fried”. Franco Citti mingles with the crowd attending (and enjoying) the ‘frying’. He sells hot frittelle (fritters) as at a sporting event.

The scene is grotesque and comic, an ironic satire aimed at the Church and its hypocrisy.

There are similar scenes of agonising death and corruption, equally absurd, ghastly and comic in Salò. And, equally, there are the mechanisms of differences, the comparative, metaphors, the linguistic formed by bodies.

Perfection

Salò is a small town in the province of Brescia in the northeast of Italy. From 1943 to 1945, it was the capital of the fascist Italian Social Republic under Benito Mussolini, created by the Nazi’s after Mussolini’s government fell to the Allies in 1943 and Mussolini was replaced by Marshal Badoglio under the Allied armies. Italy overnight went from being an ally of Germany to its enemy. Guns were turned around, friends became foes and foes friends.

Salò was created by the Nazis as a puppet government.

The 1975 Pasolini film, Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma, is based on a text by the Marquis de Sade. It begins with a round up of young boys and girls by a Fascist militia. The young people are then housed in a villa in Salò. Four libertines representing Power (sacred and profane) are in charge. They first select their victims on the basis of the most desirable, those without a blemish, those physically perfect. There would be little force or pleasure to defilement if victims were less than perfect. What could be more sublime than besmirching the pure, like the rape of nuns? There is on the one hand, Beauty and Innocence, and on the other, ugliness and corruption. They require each other, assume each other more, not for the sake of a reality, but for the sake of an opposition and a comparison, a linguistic trope, a semiotic form, and a metaphor, not one without the other.

Some of the young people, stripped naked, are rejected for the slightest physical defect: bad teeth, poor skin, eyes crossed. Only the physically perfect can be accepted to be tortured, violated, defiled, dirtied, ultimately murdered.

The scene of selection is not unlike the casting for a film (it is in fact a parody of casting) as in Fellini’s Intervista (1987). It is like throwing out a net, to catch the right, appropriate, desired, suitable, beautiful, edible fish. In movies, actors must be perfect, especially stars, especially female stars, and especially in the films of Hollywood. For Pasolini (and for the Marquis de Sade) the perfect is an opportunity not for celebration, but desecration, besmirching, the high brought low and violated.

The origin of such behaviour is the medieval Carnevale, where everything is reversed, turned upside down. It is Rabelais and later would become de Sade.

I racconti di Canterbury begins somewhat differently, most of the characters, are of the ‘people’ have bad teeth, poor complexions (blotchy, pimpled), are obese or scrawny, often ugly, decrepit, drooling, disgusting, dopey, lecherous, like the old man in The Merchant’s Tale (and like the libertines in Salò), have unpleasant grating voices. There are some few characters, however, such as the young bride whom the Merchant marries in a scene that mirrors the marriage scene in Salò, or who are perfect as in The Cook’s Tale: pretty young girls, heads covered like nuns, but otherwise completely naked, their bodies moving to music, seductive and charming, who sing and dance at a wedding celebration, joined by Ninetto Davoli. He imitates the movements of the young girls, parodies them and in so doing ‘brings out’ their movements, parody and outrage as instruments of emphasis, of highlights.

It is a paradoxical situation where the grotesque, the spontaneous, the natural function as a protest to the orderly, the decent, the reasonable, the civilised and the bourgeois, and where it is the innocent and the beautiful who are defiled … and physically eliminated. The paradox is a reversal. It is as crucial to Pasolini’s work as the comparative. In it, the despised are close to the sacred. Whores and pimps assume the costumes and manners of saints, as in Renaissance and Mannerist Italian paintings where the socially useless and the despised are depicted as High Art images, as Divine, as sublime.

Throughout Pasolini’s work, a work of extraordinary poetic force and passion, what is socially valued is decried and what is not valued, honoured. The poetic yield for Pasolini is in part its social outrage, turning what is acceptable into what is not because not natural and accepting the unacceptable because it is subversive, asserting an opposition, even if loathsome, to whatever is and whatever is established. The real crime for him is conformism. Pasolini’s work is a slap in the face to the normal and the expected, and like classic comedy, anarchic and disruptive. Pasolini is less the heir to Karl Marx (despite Pasolini’s politics and social indignation) than to Groucho, Chico and Harpo Marx, indignation and scandal enacted and made concrete, outrage as outrageous.

Epilogue

The final tale of the film is The Summoner’s Tale. A summoner is one who gives notice to others to appear in court, literally a summoner presents a “summons”, more generally, a summoner, takes or sends someone from one place to another, a transporting, in the case of this film, to Hell.

At the beginning of the tale, a friar attends the deathbed of a dying man from whom he asks a bequest to the Church. The man responds by bestowing the friar he says, with his most “precious” gift, a loud smelly fart in the face. In the next scene, a Summoner appears, played by a pretty young boy costumed as an angel and framed in a doorway as if from a painting. He transports the friar to the scene of The Last Judgement, itself a caricature. Its figures are painted in various colours, outlandish, garishly dressed as devils and acting like whores. Satan himself is painted an elaborate vulgar red. Out of his arse hole, like little turd balls (metaphors to the end, at the end—an arse hole), come noisy farts that accompany an explosion of miniature leaping devils flying through the air, as if liberated, a hellish, devilish fireworks.

Those in Hell make love: The Last Judgement as sexual orgy and absurd comedy, and, like Salò, hell on earth, and yet also reminiscent, I believe, of the lyrical and pathetic dream sequence of heaven, of angels with wings dressed in white, flying aloft in a slum in East London in Chaplin’s 1921 film, The Kid .

Chaplin was a Cockney, like Chaucer, and Chaucerian comedy is Cockney as is the Dickensian also Cockney.

Comparatives indeed.