Click here to view Knocknagow (1918)

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, authenticity—the “genuine” and the “real”, as it was often termed—was an ongoing concern for Irish-themed entertainment in America. Questions revolved around which entertainment was authentically Irish and which was not. For example, were the stories written or performed by persons from Ireland or of Irish descent? Were the costumes, makeup, and props accurate, or were they intentionally overdone for comedic effect? Did the music evoke Irish traditions, or was it merely representative of American popular song? The answers to these questions came from a variety of sources, ranging from critics to audience members, and their responses were hardly uniform. As Mark Phelan has noted, “authenticity is never stable or fixed, but is rather, capriciously chimerical and in flux” (Phelan, 236). He adds that any theatrical “reproduction of authenticity” is an oxymoron (Phelan, 237). Ascertaining the “genuine” qualities of Irish-themed American entertainment of the period was a difficult task, as illustrated by the fact that performers without Irish heritage for stage purposes sometimes became “Irish comedians”. Conversely, many persons of Irish descent commonly wrote, directed, and acted in non-Irish themed stage productions.

These issues became crucial for early American films, which had to deal not only with the perennial concerns and controversies that had plagued live entertainment in the nineteenth century, but also with new issues specific to the cinema. Many early “non-fiction” films were faked, and some of them created controversies as a result. By contrast, other films, including many fiction films, consciously strove for what was called “realism” or “the real”. As Charlie Kiel has noted:

[T]he issues of realism that had informed discussions of photography persisted in the criticism of narratives, suggesting that the fundamental question remained one of believability; the oft-repeated phrase “truthfulness to life” demonstrates the centrality of verisimilitude to the trade press aesthetic. Trade press critics understood that audience comprehension and involvement go hand in hand, always predicated on a film’s sustained cultivation of verisimilitude. (Keil, 35)

In a 1911 issue of Moving Picture World, C. H. Claudy addressed the matter more bluntly: “[W]e don’t thank you, Mr. Producer, we motion picture audiences, for forcing down our throats, the knowledge that this is only a screen and a picture—we want to think it’s the real thing”.[1]

During the early and silent eras of American cinema, Irish-themed films attempted to construct the appearance of authenticity using a number of strategies, ranging from adapting respected stage plays of the nineteenth century to shooting fiction films on location in Ireland. While individual viewers offered a range of responses to these moving pictures, the Irish-American press almost completely ignored them, including the famous American-produced “O’Kalem” films that have figured in recent scholarly discussions of indigenous Irish film production (see Rockett; Barton). Irish-American newspapers did regularly discuss issues of authenticity with regard to stage productions, literature, poetry, and artwork. Perhaps they viewed Irish-themed fiction films as inauthentic or inferior to other forms of Irish-themed entertainment. At any rate, they avoided discussing them so completely as to not even offer a justification of their reasons for so doing.

By contrast, motion pictures produced by the Film Company of Ireland caused a notable shift in the attention paid to cinema by the Irish-American press. Here at long last was a group of motion pictures that Irish-American newspapers could herald. Unlike the “O’Kalems”, these films need be neither ignored nor denigrated, as was to be the case with several movies in the ’teens and twenties which the Irish-American press perceived as offensive or British propaganda. FCOI releases were instead judged to be authentic: “real” Irish stories filmed in Ireland with Irish actors. And, importantly, unlike Kalem, the FCOI was Irish, not American, an appeal enhanced by the fact that it produced feature-length motion pictures, which, unlike the short subjects of earlier years, generally attracted more attention on theatre programmes. Furthermore, to the extent that FCOI films were nationalistic or propagandistic, they cinematically reinforced the editorial line taken by Irish-American newspapers. The FCOI’s version of authenticity thus met with immediate approval from the Irish-American press, which treated their films with a respect that it seldom afforded motion pictures, publishing numerous announcements and positive reviews of a type that changed the way in which these newspapers covered both Irish-themed fiction films and, by extension, the cinema itself.

Authenticity and the Irish-Themed Entertainment

During the post-Civil War era, as Kathleen Heininge and John P. Harrington have suggested, Irish-themed live entertainment frequently raised the question of authenticity (Heininge, 15–30; Harrington 55–74). The debate over what was and what was not “genuinely” Irish came in the form of publicity as well as in the responses of journalists and audience members who conveyed their thoughts through journalistic reportage and letters to the editors of Irish-American newspapers. Such emphasis on promoting and judging the authenticity of Irish-themed entertainment was not unique to live theatre. For example, Sister Mary Francis Clare’s novel From Killarney to New York; or, How Thade Became a Banker (1877), promised that it would “typify an incident in Irish-American life”; it was, so its title page claimed, “a story of real life”.

The hugely popular Irish-themed plays of Dion Boucicault (c.1820–90) were a key component in discussions of authenticity. In 1875, a group of Irish-Americans congratulated Boucicault for “elevating the stage representation of the Irish character”, notes Deirdre McFeely, who adds: “The mainstream, or Anglo-American, audience equally approved of Boucicault’s representation of the Irish. The theatre critics of the mainstream New York daily newspapers welcomed Boucicault’s portrayal of what they considered to be the real Irish of Ireland” (McFeely, 55). Similar sentiments appeared in the press on numerous occasions during the nineteenth century. In 1874, for example, the New York Times published an article claiming that Boucicault had “created an Irish drama, and almost driven the old-fashioned rough-and-tumble Irishman from the stage. The caricature is gone. The portrait from nature has been substituted in its steed” (15 November 1874, 7).

However, debates over authenticity hardly resulted in consensus. Barney Williams (1823–76), a comedian who, like Boucicault, had been born in Ireland, exemplifies the disagreement generated by discussions of exactly who and what was authentic. Even as early as the 1850s, Williams had been decried as a crude “imitator” of the Irish (Niehaus, 126), although such criticisms hardly deterred him and others from suggesting the opposite (Williams, 86–7). In 1869, an advertisement publicized the “genuine Irish acting” in a play titled The Emerald Ring, which was due to “Mr. and Mrs. Barney Williams in their famous characters of Mike and Maggie Macarty” (New York Herald 14 April 1869, 14). The following year, the New York Herald praised Williams for his work in Innisfallen, or the Men in the Gap, a play by Edmund Falconer, claiming that it offered “real, genuine Hibernian warmth” (22 February 1870, 4). In some ways, Williams had inherited the mantle of the Irish comedian Tyrone Power (1795–1841), who himself had been viewed as “genuine” in the antebellum era (Williams, 86).

The question of authenticity was not restricted to famous comedians and playwrights such as Williams and Boucicault. According to his own publicity, the comedian Joseph Lewis in his guise of “Barney O’ Toole” represented “real, original Irish wit and humor” (Dubois Weekly Courier, 2 February 1882, 3). An Indiana newspaper proclaimed comedian Tom Waters and his musical skit The Mayor of Laughland to be “real Irish comedy” (Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, 12 February 1908, 5). As for plays and sketches, the San Francisco Chronicle described The Ivy Leaf, a play by Con T. Murphy, as “genuine Irish drama of the school that Boucicault has made familiar” (quoted in Reno Evening Gazette, 7 March 1888, 3), while the Oakland Tribune favourably reviewed the vaudeville act A Romance of Killarney by reassuring readers that it was “genuine Irish comedy” (Oakland Tribune, 24 June 1910, 9).

Judgments as to exactly what play or performer was “genuine” were a regular matter of controversy. Debates over Irish-themed entertainment, including whether it was insulting or infused with British propaganda, were conducted in a subtle effort to sway American audiences against the Irish struggle for freedom. Conclusions reached at any given point were hardly fixed and could evolve over time. Heininge notes that “By the end of the nineteenth century, Boucicault was accused of creating a new stage Irish figure rather than eradicating the previous ones” (Heininge, 8), and Gwen Orel has shown how questions about the authenticity of Boucicault’s plays erupted in the Irish-American press in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Orel, 66–7). Even so, the National Hibernian praised Boucicault in 1904 for having “shed luster on [his] profession, and through it on the country that gave [him] birth” (15 January 1904, 4), and the Irish Monthly heralded Dion Boucicault in 1915 as an important Irish playwright in America (November 1915, 731). Examination of pronouncements like these reveals the lack of consensus, even with a narrow time period, about who and what was genuine.

The most famous case of ethnic origins being judged unimportant was the negative reaction of the Irish-American press, particularly the Gaelic American, to the staging of J. M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World in New York City in 1911—despite the fact that the same company of Irish players had already performed the play at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin (Harrington, 55–74). Indeed, Synge was renowned for what Mark Phelan has called his “scrupulous attention to details”, which included ensuring the authenticity of stage props used at the Abbey Theatre (Phelan, 237). The Playboy was not crude vaudeville comedy, nor did it represent the “stage Irishman” as this stereotyped character was known in the early twentieth century. Even so, one performance in New York in November 1911 caused a “riot”; the Billboard reported that “much refuse was thrown at the actors and the police reserves were called. Ten prisoners were taken” (2 December 1911, 40). Being recognized as authentic was no easy matter, particularly when the Irish-American press was the judge.

Irish-Themed Films

Despite the travails of Irish-themed entertainment in the nineteenth century, and the upheaval caused by Ireland’s own ongoing struggle for independence, early Irish-themed non-fiction films were distinguished by an emphasis on authenticity. This was due in part to the fact that these films were in most cases shot on location in Ireland. For consistency, they films often revisited particular locations such as the Lakes of Killarney or the Giant’s Causeway, or particular ethnographic scenes such as workers in peat bogs or Irish citizens in urban markets, which had been depicted in nineteenth-century lantern slides and stereoviews. The same sites had also been made famous by popular songs and other live entertainments.

Similarly, Irish-themed fictional films sought to be—or at least appear to be—“realistic” and “genuine”.[2] At times, this approach meant casting Irish actors or embedding Irish characters into fictional stories based on current events. In other cases, specifically Edison’s European Rest Cure (USA 1904), it meant incorporating non-fiction footage into fictional films.[3] However, such efforts to create “genuineness” were often at odds with the exaggerated ethnic caricatures that had been a feature of Irish-themed films since the earliest days of cinema. These stereotypes involved exaggerated makeup and recognizable costumes such as beards and clay pipes as well as hackneyed character traits and behaviour such as fighting and drinking (see fig. 1) . Tension between these two forces—authenticity and stereotype—is thus a hallmark of Irish-themed fiction films, and especially comedies, of the early cinema period.

The catalogue descriptions for Biddy’s Day Off and Irish Couple Dancing Breakdown, two films distributed by Lubin in 1903, similarly suggests that they featured fictional characters who engage in dancing even as they use an identical formulation—“real, old Irish breakdown”—to describe the onscreen action (Complete Catalogue of Lubin’s Films, 52, 68). Lubin also promised that Irish Reel, with its apparently fictional characters Biddy Murphy and Mickey Roach, included a “real Irish reel” (Complete Catalogue of Lubin’s Films, 68). Despite the claims implied by their publicity, these films were all shot in America, possibly with non-Irish cast members. As such, they have more in common with American Mutoscope and Biograph’s Why Mrs. McCarthy Went to the Ball (1900), whose title character “drops into a jig” at a dance, than with non-fiction cinema (Picture Catalogue 35).Although most Irish-themed comedies produced in America featured stories set in America, this did not deter film companies from promoting their Irish authenticity. For example, the F. M. Prescott film catalogue of 1899 describes Christening Murphy’s Baby as a “real Irish christening” featuring a “genuine ruction” after the characters “imbibe too much of the flowing bowl”; the rest of the synopsis, which concludes by promising that the film is a “corker,” reveals that Christening Murphy’s Baby is a fictional comedy (Catalog of New Films, 70). The film may have been neither “real” nor “genuine” but Prescott did not hesitate to claim otherwise.

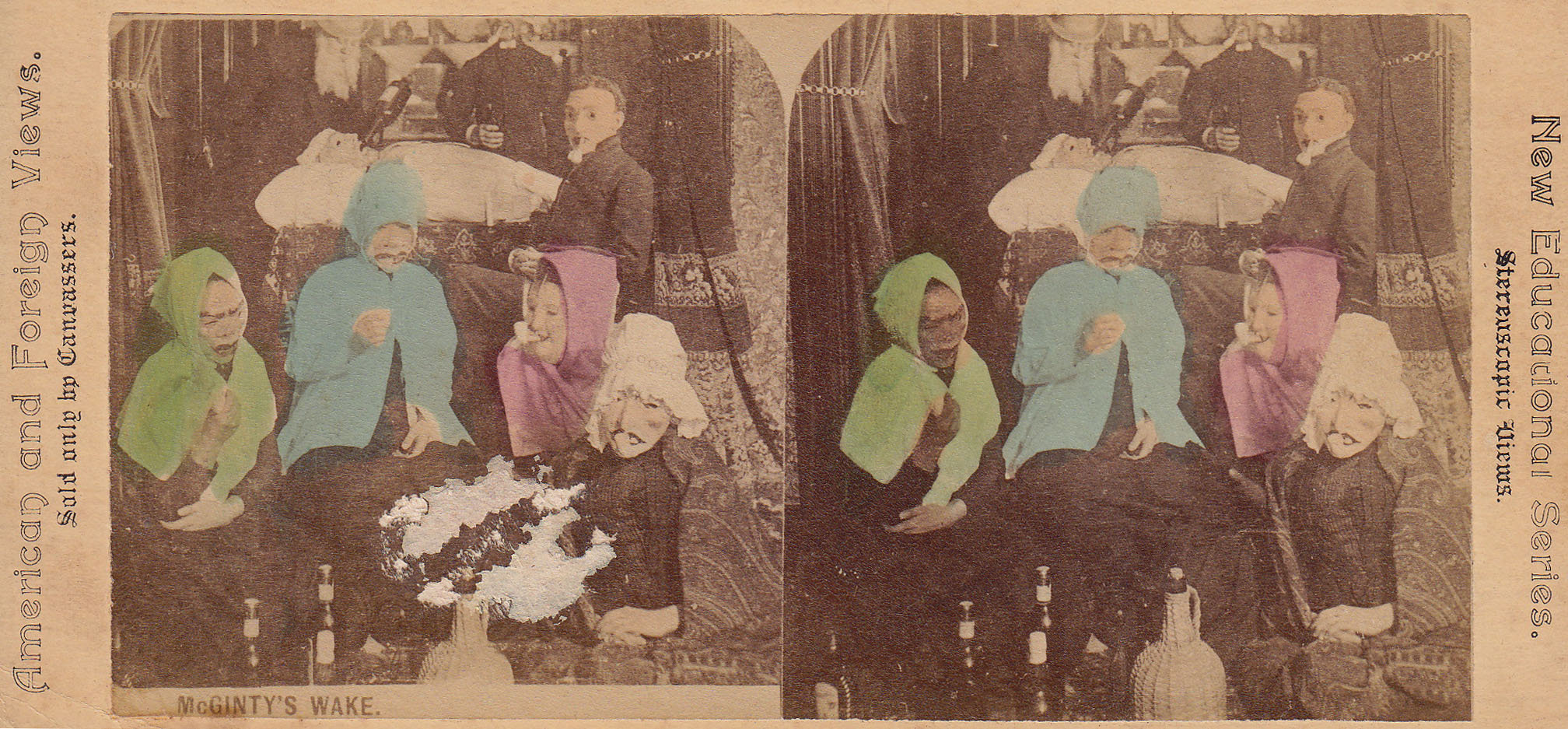

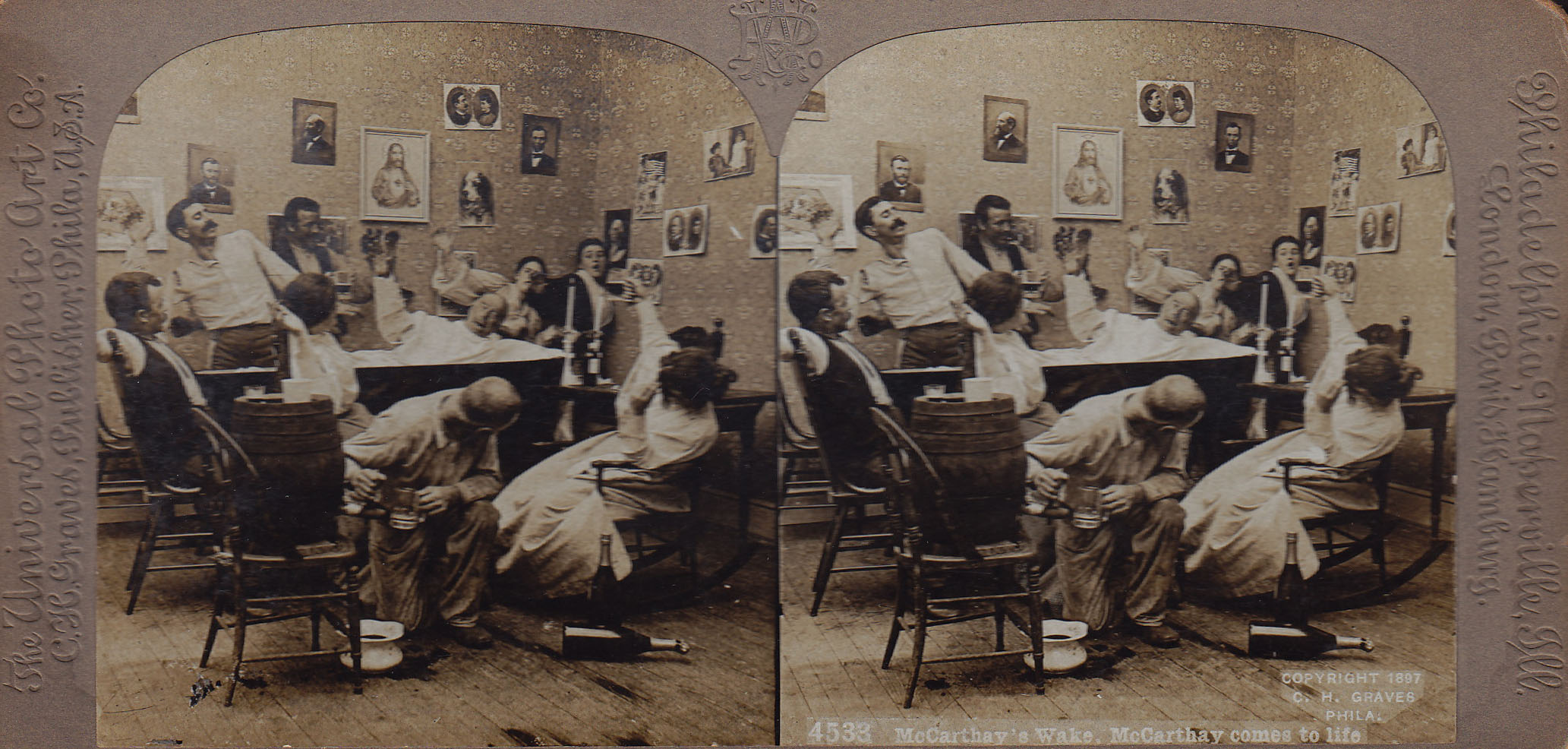

Other comedy films sought to build a degree of authenticity by adapting pre-existing fictional works which already had credibility with audiences. The Gaumont-British film Murphy’s Wake, released in the United States in 1903 (New York Clipper, 21 November 1903, 944), was an adaptation of a sequence from Boucicault’s play The Shaughraun (1874).[4] Using an approach for which Kalem would later become famous, this was the first attempt to adapt for the screen a noted and (for many general American audiences and at least some Irish-Americans) respected stage play with an Irish theme. At the same time, and in further illustration of the tension between authenticity and ethnic stereotype, Murphy’s Wake drew upon the larger culture of Irish wake humour that had been a prominent feature of nineteenth-century vaudeville acts, comic lantern slides, and comic stereoviews (fig. 2 and fig. 3 )—few of which could be called “genuine”.[5]

However, the most common resource for “genuine” Irish film narratives were those nineteenth-century stage plays, such as Boucicault’s, which continued to enjoy popular success in America. The intermedial quality of pre-nickelodeon Irish-themed films, which depended on the audience’s knowledge of a given tradition such as vaudeville humour, became less important to these “genuine” Irish-themed films, which often featured story structures founded on an idea of unity intended, as Keil notes, “[to] bind together the stages of the narrative’s progress” (Keil, 53). Titles and inserts aided the narration, allowing viewers without prior knowledge of the original stage play to makes sense of the film.While the pre-nickelodeon era is rife with examples of comic fiction films featuring Irish stereotypes, it was not until the start of the nickelodeon era, approximately ten years after the first public film screenings in the United States in 1896, that American moving picture companies began producing dramatic Irish-themed fictional films that eschewed ethnic caricature. Moving picture companies that wished to create “real” Irish-themed films usually sought to adapt pre-existing works, sometimes even turning to nineteenth-century music or poetry. The Edison Manufacturing Company was the first to produce films of this kind with its 1906 version of Kathleen Mavourneen, and subsequent efforts included Vitagraph’s The Shaughraun (1907), and An Irish Hero (1909), Selig Polyscope’s Shamus O’Brien (1908) and A Daughter of Erin (1908), and Thanhouser’s Robert Emmet (1911).

At the same time, moving picture companies in the nickelodeon era chose to adapt Boucicault’s Irish-themed stage plays. They did so for two connected reasons. First, the popular success of Boucicault’s plays across the United States during the final decades of the nineteenth century meant that their titles and stories remained well known. Film adaptations drew on this enduring fame; whether or not audiences had seen the original stage plays mattered less than the fact that they had heard of them, a factor of great importance for their marketing. Second, the film adaptations attempted to harness for their own ends the respectability of plays that had been embraced by critics and audiences alike. The desired result was a film that would be seen as authentic, and Boucicault’s Irishness, coupled with the frequency of Irish words and names in the titles of his plays and their dialogue, reinforced the general audience’s perception of their realism.

These Irish-themed fictional films also marked a change in that their narratives, unlike those of comedies, were often set in Ireland. Their Irish setting became a regular feature of publicity promoting the authenticity of these films. For example, the producers of The Irish Blacksmith (USA 1908, Selig Polyscope) promised that it possessed “scenery marvellously faithful to the locality in which the dramatic events take place”.[6] Locations such as Blarney Castle that had long been depicted in non-fiction lantern slides were a common feature of these settings, and were factored heavily into the narrative of Come Back to Erin (USA 1911, Powers) (Moving Picture World, 11 March 1911, 549). Film companies such as Kalem tried to add greater realism to Irish scenes by shooting on location in Ireland. A reviewer of Kalem’s The Shaughraun (1912) announced that the film, having been shot “upon Irish soil”, was as a result “accurate in every detail” (Waterloo Reporter, 17 March 1913, 5); such claims pointedly differentiated the film from earlier adaptations of Murphy’s Wake in 1903 and 1906. For some film critics and, presumably, some general audiences, the mere fact that Kalem shot its films on location provided verisimilitude, irrespective of the actors’ ethnicity, the costumes, or Boucicault’s storyline.

Even Kalem’s less well-known Irish-themed films tried to create an aura of authenticity by including footage of Irish locations with which general audiences had been made familiar by decades of non-fiction lantern slides, travel lectures, stereoviews, and films. For example, advertising for The Irish Honeymoon (USA 1910, dir. Sidney Olcott), a fiction film, invited audiences on “a bridal tour through the beautiful scenic sections of the Emerald Isle”, promising that they would “See the actual feat of kissing the Blarney Stone” and promoting the same kind of authenticity as had Gaumont’s non-fiction film Kissing the Blarney Stone (1904). Kalem even appended the subtitle A Trip through Ireland to The Irish Honeymoon in an echo of numerous non-fiction travel lectures of the nineteenth century as well as of non-fiction moving pictures such as Hale’s Tours’ Trip through Ireland (USA 1906) and Trip through Ireland (USA 1906, Lubin) (Film Index, 4 March 1911, 21). Yet the Irish-American press never mentioned The Irish Honeymoon.

The Irish-American Press and American Cinema

The key Irish-American newspapers of the early cinema period—the Gaelic American, Irish-American, Irish-American Advocate, Irish World and American Industrial Liberator, National Hibernian, and Pilot—printed very few articles on moving pictures and notably few on Irish-themed fictional films.[7] Published in and around New York and Boston, these newspapers (apart from the monthly National Hibernian, all weeklies) catered to Irish-Americans across the United States, supplying news of Ireland and Irish-America that ranged from the Irish independence struggle to critiques of Irish literature and stage productions. Before exploring the possible reasons why these newspapers addressed cinema so irregularly, it is important to note that they did not coordinate their reportage or editorials. For example, the Gaelic American frequently decried editorial positions taken by the Irish World.

Does the lack of coverage of moving pictures suggest an effort, albeit uncoordinated, on the part of these newspapers to appear more upstanding and middle-class? It is highly unlikely given that they did publish articles on moving pictures that were often positive in tone. In 1896, the Irish-American reported on the “wonders of the Lumiere Cinematographe at Keith’s Union Square Theatre” in New York City (3 August 1896, 1; 17 August 1896, 5; 31 August 1896, 4; 14 November 1896, 8.). In 1909, the Irish-American Advocate ran a brief story about an exhibition of “the first [moving picture] views of the Italian earthquake” (30 January 1909, 3). Two years later, the Irish-American reprinted part of a Chicago Tribune article on “Moving Pictures and the Eyes” dealing with current fears about film viewing as a danger to eyesight (3 June 1911, 4). It later published two brief articles on Kinemacolor and an article on “movies” written by a theatrical manager (18 January 1913, 8; 22 August 1913, 8; 21 February 1913, 2). And in 1912, the Pilot announced that Pope Pius X had witnessed a moving picture show featuring images of the “inauguration of St. Mark’s Campanile at Venice” (13 July 1912, 1). Articles such as these differ little from the moving picture news that was published in newspapers for general audiences, and hardly suggest a boycott of the subject.

In keeping with film coverage by other newspapers, the Irish-American press occasionally published concerns about “immoral films” and the necessity of censorship in much the same way as they from time to time wrote about “evil” and “immoral” dime novels, comics, and—above all—stage plays.[8] While the Irish-American printed one article about “insidious” moving pictures (25 January 1913, 6), the Pilot took the lead, unsurprisingly, given that of all the Irish-American newspapers it was the most consistent and outspoken on religious issues. Between 1910 and 1911, it printed three articles on the “Moving Picture Nuisance” (3 September 1910, 4; 8 October 1910, 4; 2 December 1911, 4). These articles, which make no mention of Irish-themed films, offer early examples of the religious opposition to the depiction of murder and sexuality in cinema that would lead to the formation of the Legion of Decency in 1933.

Had their readership, which consistently made its voice heard through letters to the editors, at any point during the early cinema period desired coverage of Irish-themed moving pictures, one or more of these Irish-American newspapers—particularly those New York titles that were in competition with one another—would likely have acquiesced. In short, these six newspapers seem to have largely avoided coverage of Irish-themed moving pictures at this time because they did not perceive sufficient interest among readers. To be sure, it is far from certain that all Irish-American viewers, especially children, preferred films with Irish themes. It is also quite possible that many Irish-Americans saw moving pictures as little more than a tangential feature of their daily lives. Indeed, during the pre-nickelodeon era and the nickelodeon era venues screening films often did not trouble to announce the titles of specific films. Many nickelodeons changed films regularly, some on a daily basis. Unlike a play, which might be touted in advertisements and staged on numerous occasions, some Irish-themed films would have disappeared from nickelodeons even before their existence became widely known.

What is certain is that Irish-American newspapers of the pre-nickelodeon era did not complain about the many cinematic depictions of the stage-Irish. They did not mention Edison’s Irish Way of Discussing Politics (aka Irish Political Discussion and Irish Politics) (USA 1896, Edison), Pat and the Populist (aka Pat Vs. Populist) (USA 1896, Edison), or any of the other early Irish-themed moving pictures. Some newspaper editors and readers may have disapproved of these comedies, which appeared year after year, but they did not bother writing about them. In 1910, the Irish-American Advocate briefly noted a negative reaction to the “usual makeup of the stage Irishman … on the canvas” at a Brooklyn nickelodeon whose manager had complied with a female patron’s request that the films be “withdrawn” (26 March 1910, 1). Yet such criticism of the stage-Irish in film almost never found its way into print.

By contrast, the Irish-American and other Irish-American newspapers regularly editorialized against “stage Irish” characters in live theatrical and musical performances. In June 1902, the National Hibernian spoke out against such stereotypes, citing the continued performance of Drill Ye Tarriers, Drill, a song written in 1888 which inspired American Mutoscope and Biograph to release a film of the same name in 1900 (15 June 1902, 4). However, the National Hibernian did not mention the film version, either explicitly or implicitly. Instead, editorials usually focussed on offensive stage plays and vaudeville acts, both well-publicized events that were often performed repeatedly at the same venue. Offensive sheet music and post cards were also a concern, as they might be sold in stores for months at a time. The fact that individual moving pictures in this period were not usually advertised by title, the fact that they were embedded within larger film programmes (themselves often just a feature of still larger vaudeville bills), and the fact that they were sometimes screened for only a day or a few days all probably account for why film proved to be too small a target for editorial foes of the “stage Irishman”.

Apart from two advertisements in the Irish-American Advocate promoting screenings of Edison’s Kathleen Mavourneen in 1906 and 1907 (1 December 1906, 4; 20 April 1907, 8), Irish-American newspapers in the years prior to 1915 generally ignored Irish-themed dramatic films. None of the six aforementioned Irish-American newspapers mentioned the “O’Kalem” fictional films, whether to describe the novelty of their Irish locations, to announce their release, or even advertise screenings. Nor did they publish any articles on Irish-themed fictional films produced by companies other than Kalem. If one had to rely on Irish-American newspapers for information about these films, it would be as if they had never existed—in stark contrast to the consistent coverage given by each of these publications to Irish dance, literature, stage plays, and other entertainments.

Between the dawn of projected film and 1915, the main Irish-themed films mentioned by Irish-American newspapers were non-fiction films, a logical extension of the coverage they had given to travel lectures featuring non-fiction lantern slides during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. For these newspapers, such moving pictures exemplified the “real.” Even so, their coverage was still quite brief, and mostly appeared in the Irish-American Advocate, which sponsored screenings of Irish-themed films in 1905. An advertisement for one of them promised:

Plenty of Fun and amusing incidents in the trip that are side splitting with humour. These pictures are faithful reproductions of live and interesting places in Ireland. They were taken last summer and many of the places and scenes will be familiar to every reader of this paper. The entire series of thirty odd views will be equal to a tour of Ireland. (11 February 1905, 4)

In 1907 and 1909, the Irish-American Advocate promoted similar screenings of non-fiction films, presumably because it was again a sponsor (8 March 1913, 1; 27 February 1909, 8).

During the early cinema period, the Irish-American press thus ignored fictional Irish-themed moving pictures and gave only scant coverage to non-fiction Irish-themed films. The only American-produced film about Ireland covered at any length by the Irish-American press the feature film Ireland a Nation (USA 1914, dir. Walter MacNamara). This five-reeler recreated key moments in Irish history, particularly the independence struggle, including non-fiction footage of a Home Rule meeting in 1914, and, on later reissues, non-fiction footage taken in 1919 and 1920. In addition to covering the release of Ireland a Nation, Irish-American newspapers reported on it many subsequent reappearances, including a screening at a “Monster Irish Entertainment and Ball” in New York City on St. Patrick’s Day, 1915 (Irish-American Advocate, 6 March 1915, 7). Two years later, the film was again shown in New York at the Twelfth Annual Irish Ball and at a “Monster St. Patrick’s Night Celebration and Entertainment” organized by the Ancient Order of Hibernians (Gaelic American, 13 January 1917, 8; Irish-American Advocate, 20 January 1917, 8; Irish World, 10 March 1917, 12; Irish-American Advocate, 24 February 1917, 8.).

However, Ireland a Nation received its most extensive promotion in the Irish-American press after the end of the early cinema period, when it was reissued by the Gaelic Film and Amusement Company in 1920. Rather than mentioning director Walter MacNamara, publicity materials concentrated on Emmett Moore, who is probably the most overlooked figure in the history of the Irish-themed film in America. His re-edit of Ireland a Nation played three weeks that year in Manhattan at the Lexington Theatre on a program also featuring “Larry Reilly with his Irish Pipers” (Gaelic American, 3 April 1920, 8; Irish-American Advocate, 3 April 1920, 8, and 10 April 1920, 6; Gaelic American, 17 April 1920, 8, and 24 April 1920, 8). It then moved to the Standard Theatre for one week (which included a personal appearance by Emmett Moore), after which it played for two weeks at the Manhattan Opera House (Irish World, 1 May 1920, 6; Irish-American Advocate, 1 May 1920, 6; Gaelic American, 1 May 1920, 5). Ireland a Nation also appeared in Brooklyn’s Academy of Music on a program including “Irish songs” and “an all-star series of Irish vaudeville”, after which it was screened for one week at the city’s Montauk Theatre (Gaelic American, 13 March 1920, 8; Irish-American Advocate, 13 March 1920, 6, and 22 May 1920, 6; Gaelic American, 22 May 1920, 8; Irish World and American Industrial Liberator, 22 May 1920, 6). An advertisement in the Gaelic American announced that “President De Valera has personally sanctioned Ireland a Nation as a picturization of the reality” (13 March 1920, 7).

The Irish-American press directed a great deal of attention to Ireland a Nation, even while regularly ignoring other Irish-themed fictional films. Since they did not comment on the fact of MacNamara’s having been born in Ireland, and even ignored him when the film was reissued, his background seems not to have played a role in their coverage. They were likely drawn to Ireland a Nation’s feature-film length, its use of non-fiction footage of Ireland (an area of the cinema in which the Irish-American press had expressed only slight interest), and perhaps most particularly its perceived propaganda value in the United States, where Irish-American newspapers were concerned at the screening of British propaganda films in theatres. Indeed, the phrase “Ireland a Nation” had itself appeared repeatedly in news reportage and editorials in newspapers such as the Gaelic American. At any rate, the Irish-American press’s coverage of Ireland a Nation provided a template for how it would cover the Film Company of Ireland.

The Film Company of Ireland

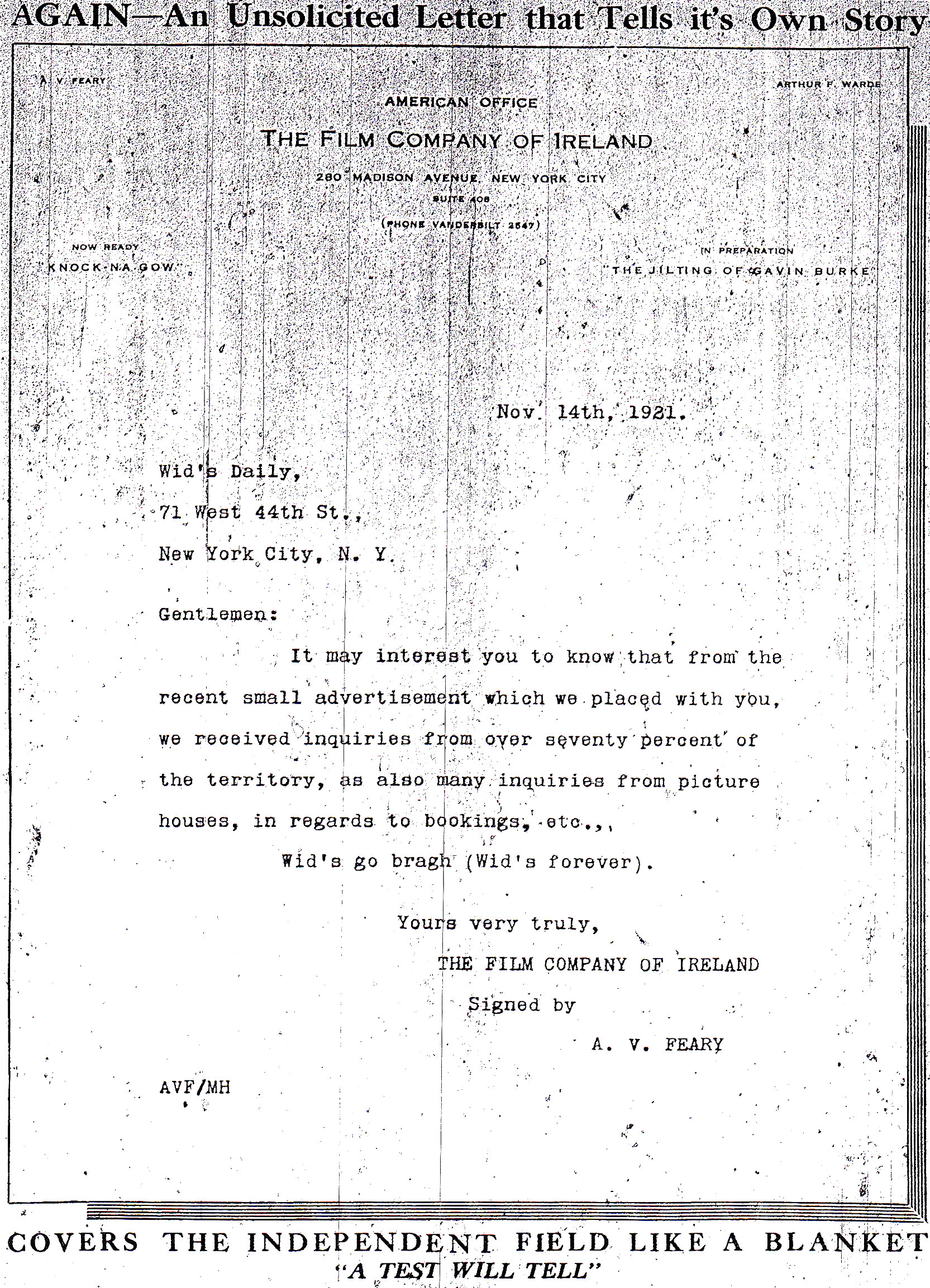

The Irish-American press heralded the arrival of FCOI films at screenings sponsored by the “Irish Film Company of America” (fig. 4) . The first FCOI screening took place at the Tremont Temple in Boston on December 9, 1918. The Pilot reported large ticket sales for an “opening exhibition” at which viewers would receive free “souvenir picture card[s]” of actor Bryan Magowan (7 December 1918, 7). The screening featured an eight-reel version of Knock-Na-Gow, or The Homes of Tipperary (also known as Knock-Na-Gow and Knocknagow, 1918), which headlined advertisements in the newspaper together with a “two-reel comedy” Widow Malone (1916) as a further attraction. The Tremont Temple’s advertisements also promised viewers: “See the beautiful scenery of all the counties of Ireland. One reel of which will be given each afternoon and night” (30 November 1918, 5). Introducing the various films was an array of live music, including organ and piano solos and a ten-piece orchestra that would present “many of the well-known melodies that have characterized Ireland’s music for centuries” (Pilot, 7 December 1918, 7).

The Irish atmosphere is remarkably reproduced in this picture play, it would be impossible to create it by the mere acting and scenery of the conventional drama. The hunt, the hurling match, the wedding festivities, the renting eviction are typical of the “Fields and Homes of Tipperary”, while a tinge of pathos is added by the daughter’s deathbed scene “neath the thatched roof of the humble tailor. The reuniting of the lovers in America and their return to Ireland, as well as other leading characters who had gone abroad, concludes the romance, deftly unfolded”. (14 December 1918, 2)The following week, the Pilot reported that the Tremont had been “crowded all the week, afternoon, and evening, by delighted audiences gathered to witness the first presentation in America of the great photoplay Knock-Na-Gow”:

Ignoring Widow Malone, the Pilot’s review lauded the added attraction of non-fiction images of Ireland, although its description of them as “over one hundred views” sounds more like a description of magic lantern slides than the promised film footage.

To help promote a third week of screenings at the Tremont Temple, the Pilot continued to publish articles on the film and advertised “special prices at the matinees for children” and the arrival of “new” non-fiction “scenery” of Ireland (21 December 1918, 6) (fig. 5) . As December 25 drew nearer, the newspaper promised readers that Knock-Na-Gow had “many features of a Christmastime interest”:

In light of the approaching holiday, The Pilot predicted that Knock-Na-Gow would attract its largest audiences during its third week.One of the inspiring scenes of the play is the assembling of the people on Christmas morning for early Mass in the town of Mullinahone in Tipperary by “Mat, the Thrasher”, while later on the interior of Maurice Kearney’s house is shown with a magnificent breakfast scene, wherein is displayed all the refinement and culture of the Irish gentleman’s home, surrounded by his wife, beautiful daughters, and guests. (21 December 1918, 6)

Knock-Na-Gow ended its run at the Tremont Temple in early January 1919. For its fourth and final week, The Pilot continued its coverage by reminding readers that the film was authentic:

In order to get the opening scene of the play which represents the Village of Kilthubber of the Book, it was necessary so that no 1917 costume would spoil the atmosphere, that the village be given up to the [film] company by the people for an afternoon. . . . Thousands of people came from all parts of Tipperary and Waterford to witness the camera at work.

The scenes were all laid around Kickham’s own home and “The Homes of Tipperary” were the ones that nestled under the giant sentinel Slieve-Na-Mon. In many instances descendants of the Kickham characters in Knock-Na-Gow (though to be sure he used fictitious names) are to be found in the old homesteads that he depicted, and to their generous courtesy much is owed in giving this picture a touch of reality seldom achieved. (28 December 1918, 6)

The Pilot concluded that Knock-Na-Gow, more than just a “telling of the joys and sorrows of an Irish Hamlet”, was “symbolic of life in the dear old home land as it was lived in the nineteenth century”.

Nearly two years later, Knock-Na-Gow was finally screened in New York State, where it formed part of the annual “entertainment and ball” organized by The Waterford Men and Ladies’ Association at the Yorkville Casino on 4 December 1920. The Irish-American Advocate told its readers that the film’s New York premiere would “be an attraction for those interested in the present Irish movement” (20 November 1920, 2). However, Knock-Na-Gow’s most publicized New York appearance came four months later at the 63rd Street Theatre (also known as the 63rd Street Music Hall) in New York City where it opened on 16 April 1921 together with an FCOI two-reeler, The Miser’s Gift (1916), and “high class Irish vaudeville talent” (Irish-American Advocate, 9 April 1921, 8). Advertisements in the Irish-American press promoted the fact that Knock-Na-Gow was “Presented by the Irish Film Co. of America—the only company in America promoting Irish Photo-Plays made in Ireland by Irish Actors” (Gaelic American, 9 April 1921, 8; Irish American World, 9 April 1921, 10). The Gaelic American later reported that the theatre was “being filled to capacity at each performance”, adding that members of the Tipperary Men’s and Ladies’ Association and the Tipperary Hurling and Football Club would converge at the screening on 17 April to make it “Tipperary night” (16 April 1921, 2).

In a separate review of the film, which it referred to as “Knocknagow, or the Homes of Tipperary”, the Gaelic American praised its authenticity:

All the charm, humor and pathos which [novelist Charles J.] Kickham put into his work is reflected in its picturization, which is a credit to the Film Company of Ireland. The acting in this photo-play was done and the camera . . . was operated in the very locality which Kickham loved and of which he wrote.

The actors did their work under the shadow of old Slievenamon, and the little Anner River meanders through the plot, reviving memories of the “lily of the mountainside, who withered far away”. (23 April 1921, 5)

For the Gaelic American, the film owed its realism not only to having been produced in Ireland with Irish actors, but to its fidelity to Kickham’s novel. In other words, Knock-Na-Gow represented something wholly different from anything the reviewer had ever seen. It was “real” for reasons that had eluded American-produced films.

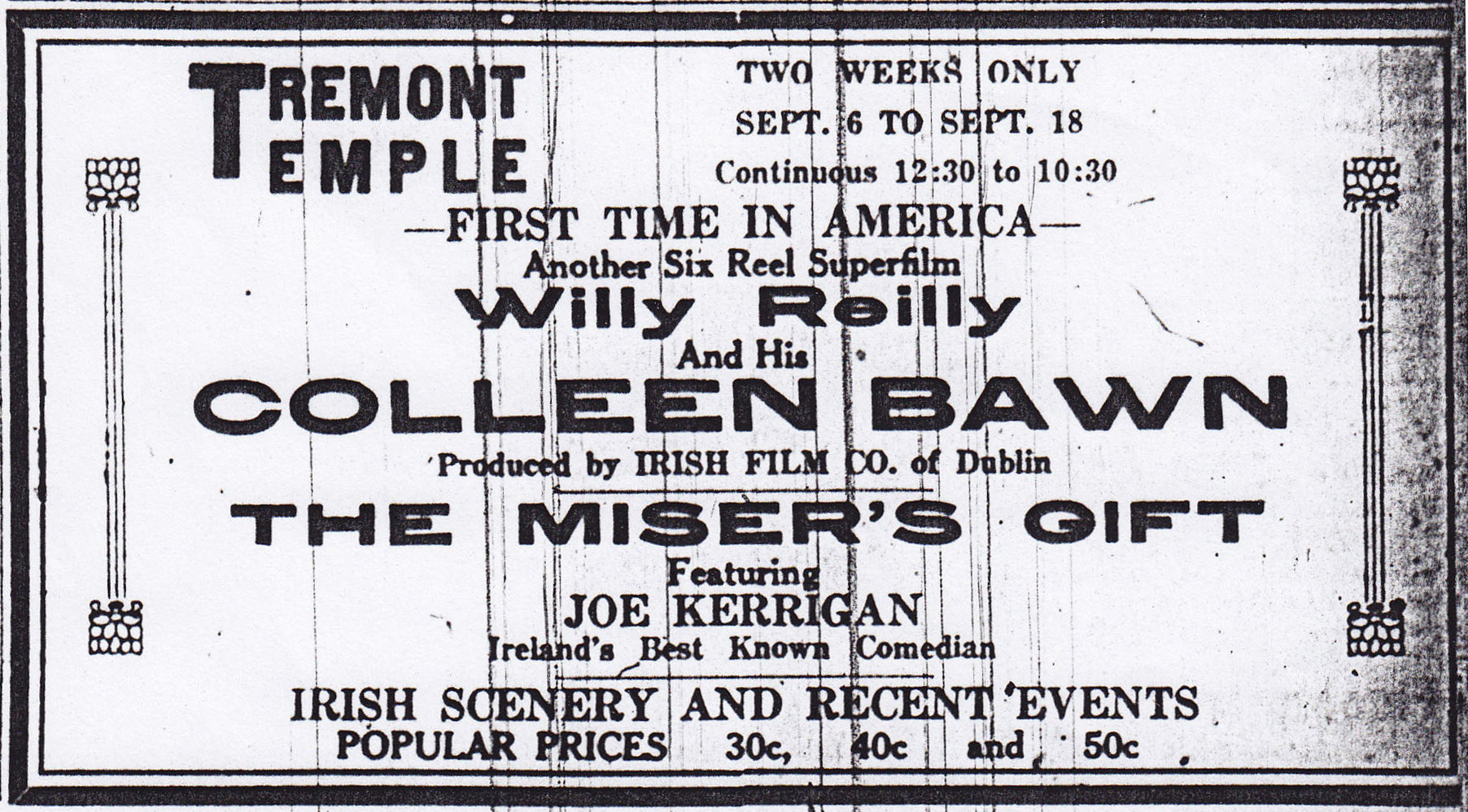

The Irish-American press gave similarly extensive coverage to the FCOI’s six-reel film Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn (1920). As with Knock-Na-Gow, Willy Reilly made its inaugural American appearance at the Tremont Temple in Boston, where it ran for two weeks in September 1920 on a bill with The Miser’s Gift and non-fiction footage referred to as “Irish Scenery and Recent Events” (fig. 6) . Willy Reilly received the top billing and was heralded by the Pilot as a “Superfilm” (4 September 1920, 3). In its review, The Pilot noted the favourable reception given by Tremont audiences and summarized the film’s many strengths:

The newspaper concluded by describing Willy Reilly as “best that has come from the Irish Film Company at Dublin”.The magnificent scenery developed in connection with the production has appealed strongly to all those who have attended. The photography is excellent and the acting of the characters by the players is all that could be wished. Especially pleasing is the admirable character of Helen Folliard, the Squire’s daughter, which is taken by Miss Frances Alexander, a Dublin girl. In the role of the Colleen Bawn, Miss Alexander has already won the hearts of all those who have seen the new photoplay, while Brian Magowan, as “Willy Reilly” commands the same admiration that came to him in the production of Knock-Na-Gow. Dermid O’Dowd, National Treasurer of the Sinn Fein in Ireland, takes the part of Squire Folliard. (11 September 1920, 7)

Approximately four months later, Willy Reilly had its New York State premiere on 9 January 1921 at the Yorkville Casino on a bill with Irish Scenery and Recent Events, as well as a “programme of Irish vaudeville talent” and “Professor McNamara’s orchestra” (Gaelic American, 1 January 1921, 8). The Irish-American Advocate published two lengthy articles on the film, the first a preview of the film:

Thousands of Irish folks have been spending their Sunday afternoons and evenings at Proctor’s and Loew’s and other local theatres. They seldom see a real Irish motion picture doing justice to Ireland and the Irish owing to the fact that the British censor refused to allow such pictures to be imported. Those who desire to see a real Irish motion picture will be given an opportunity to see one Sunday evening. (1 January 1921, 2)

The Advocate’s second article, published after the screening, claimed that the venue had been so crowded that large numbers of would-be viewers were turned away. It also assured readers that the film was “realistic throughout” (Irish-American Advocate, 15 January 1921, 4).

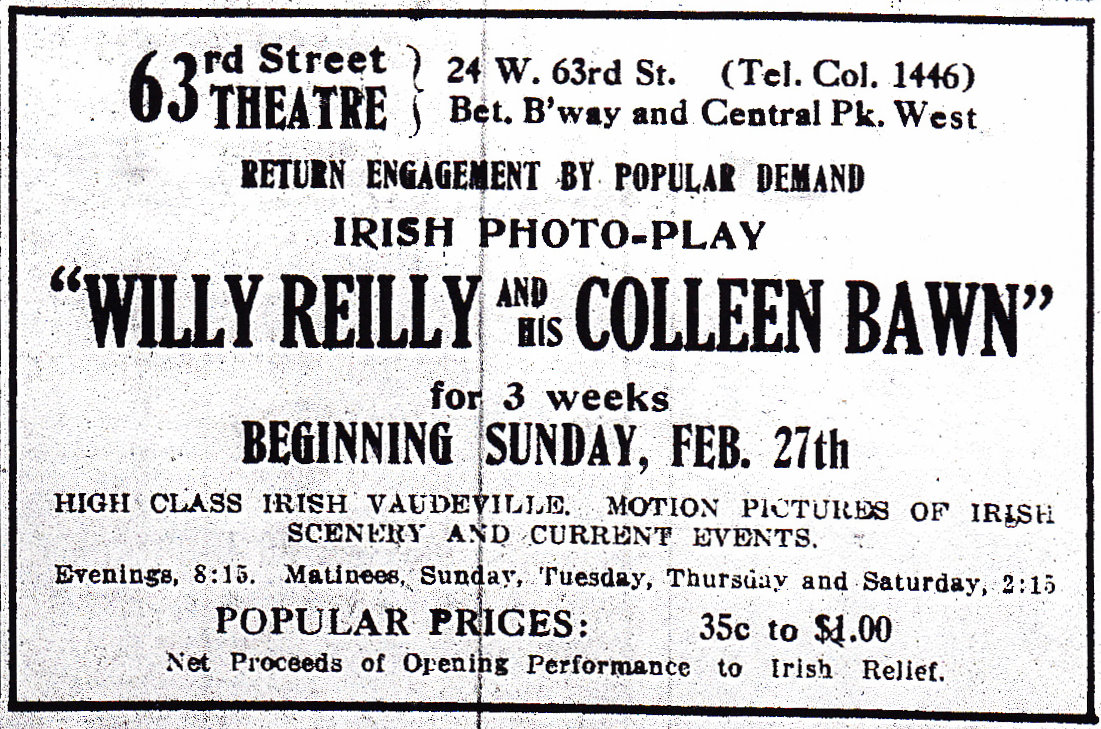

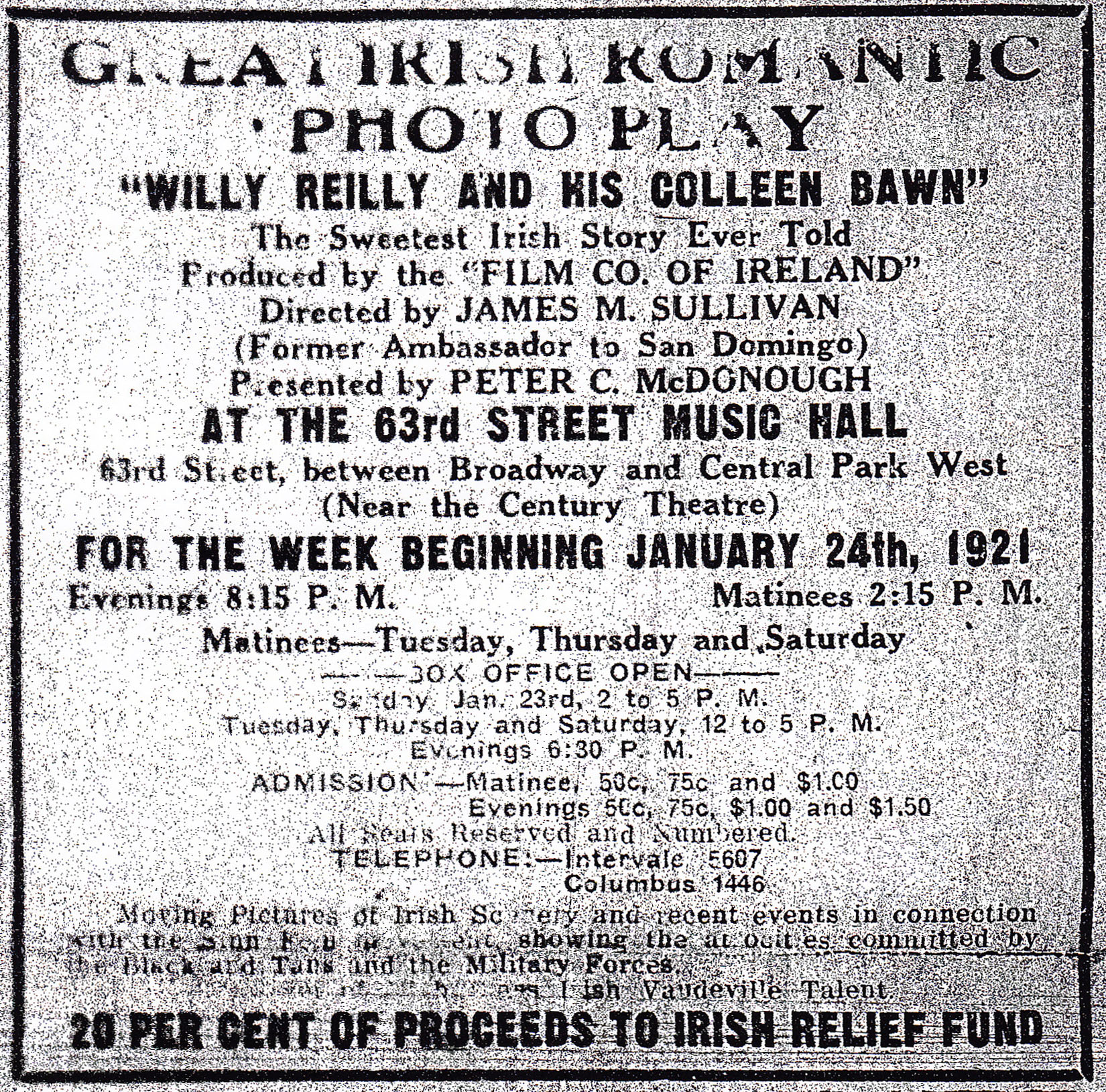

Later that month, Willy Reilly, Irish Scenery and Recent Events, and a vaudeville show appeared for six evening performances and three matinees at the 63rd Street Theatre in New York City (Irish World, 22 January 1921, 10) (see fig. 7) . Twenty percent of the proceeds went to the Irish Relief Fund (see fig. 8 ) . The shows proved so successful that Willy Reilly returned to the same venue for a scheduled three-week run staring on 26 February (Gaelic American, 5 March 1921, 8; Irish-American Advocate, 19 February 1921, 2; Irish World, 26 February 1921, 6.). All proceeds from the first night’s performance were donated “to the relief of the victims of British atrocities in Ireland” (Gaelic American, 19 February 1921, 2).

awaken many tender memories of childhood days and nights in Irish homes, listening to the familiar tale told, read, and sung around the fireside of the mansion or the blazing hearth of the cabin. In a series of thrilling scenes, splendidly acted by Irish actors in Ireland, and with photography which equals the best in the world, this photo play is linked together with superb art, and holds the attention of the audience in a firm grip to the close. (19 February 1921, 2)Discussing this return performance, the Gaelic American wrote that Willy Reilly would:

In another article, it stressed that the film had been “brought from Ireland, where it was produced with the real Irish settings” (5 March 1921, 2). The Irish World reported that the 63rd Street Theatre had been “crowded” at every performance (12 March 1921, 14), apparently a true statement since Willy Reilly was eventually screened there for more than three weeks, ending on 1 May 1921 (Irish-American Advocate, 30 April 1921, 8).

Knock-Na-Gow and Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn returned to a few American screens in 1927 and 1928 (fig. 9) , presumably due in part to the fact that the Irish-American press, led by the Gaelic American, had become involved in a heated battle with Hollywood studios over ethnic caricatures in films such as The Callahans and the Murphys (USA 1927, dir. George Hill). Revival screenings of FCOI features served as an important example of “real” and “genuine” Irish films that gave the lie to the “stage Irish” stereotypes of Hollywood.

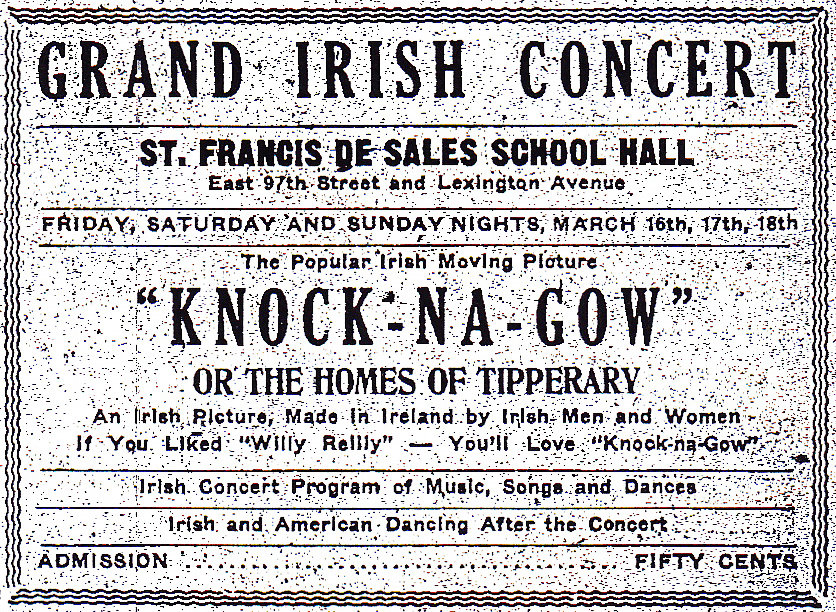

Yet Knock-Na-Gow and Willy Reilly were by this time being represented by Irish Photo Plays, Inc., a company based in New York (National Hibernian, November 1928, 3). The “authentically” Irish films had outlived the companies that originally produced and distributed them.Willy Reilly was the first to reappear, playing at St. Augustine’s in Brooklyn during the Irish Festival Week in June 1927 (Gaelic American, 4 June 1927, 5). The Brooklyn Academy of Music then screened the film on numerous occasions in January 1928 (Irish-American Advocate, 21 January 1928, 2, and 28 January 1928, 4). In March, Knock-Na-Gow was the featured attraction at a “Grand Irish Concert” staged at New York’s St. Francis De Sales School Hall (Irish-American Advocate, 17 March 1928, 3). The following month, the Clan-na-Gael of Western Pennsylvania screened it twice in Pittsburgh as an example of a truly “Clean Irish Film”—apparently because it lacked what were felt to be ethnic slurs in Hollywood films such as The Callahans and the Murphys (Gaelic American 14 April 1928, 8)—and on Thanksgiving Day, the Hibernians of Baltimore (who had earlier screened Willy Reilly) showed it as an example of motion pictures “Made in Ireland” (National Hibernian, November 1928, 3).

Conclusion

Just as articles in Irish-American newspaper on Ireland a Nation had paved the way for Knock-Na-Gow and Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn, so, too, did coverage of the FCOI influence press reporting of later fiction films shot in Ireland. Needless to say, the influence cannot be localized at the level of word choice or graphic design on the printed page. Rather, it lies in the very fact that subsequent Irish fiction films received any coverage at all, as would not have been the case prior to the FCOI releases. The Irish-American Advocate published three favourable articles promoting In the Days of Saint Patrick (Ireland 1920, dir. Norman Whitten), a feature film produced by the General Film Company of Ireland (8 January 1921, 4; 15 January 1921, 4; 22 January 1921, 6), and later promoted the feature film Irish Destiny (Ireland 1926, dir. George Dewhurst) (7 January 1928, 2). But Irish-American newspapers did not give either movie the same amount of coverage as they had the FCOI’s releases, which they evidently regarded as the pinnacle of Irish film production during the silent era.

Indeed, for at least a few years, Irish-American newspapers continued to praise the FCOI’s films as exemplary of “genuine” Irish motion pictures. Like Ireland a Nation, films such as Knock-Na-Gow and Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn embodied a kind of authenticity which Irish-American newspapers valued, one that led to their receiving positive reviews and extended coverage which the Irish-American press gave to no other Irish-themed films produced by American companies in the early and silent film periods. By 1925, the National Hibernian—which had continued to ignore American-produced Irish-themed films, with the exception of a few that it considered particularly offensive—lamented that “the Irish do not make any films of their own” (June 1925, 4). Two years later, it called for the production of educational films on Irish history and began to lobby for increased film production in Ireland, claiming that “There are few Irish photo-plays and still fewer pictures which reflect the psychology of the Irish people” (March 1927, 4; May 1927, 4).

Such laments, which derived at least in part from the demise of the Film Company of Ireland, offer an insight into the dearth of positive Irish-American press coverage of Irish-themed films produced by American firms. Irish-American newspapers arguably appreciated the FCOI not only because it was an Irish company that produced films in Ireland using Irish stories and actors, but because its films reflected what they believed to be “psychology of the Irish people”: even if the films were propagandistic, the Irish-American newspapers agreed with their bias. In a time when authenticity in Irish-themed entertainment in America was a chimerical quality, the FCOI provided the Irish-American press with a brand of cinematic realism that finally seemed real.

Images

Figure 1. George Cooper, Cooper’s Irish Dialect: Readings and Recitations (New York: Wehman Bros, 1891).

Figure 2. C. H. Graves, “McCarthy’s Wake: McCarthy Comes to Life.” Undated stereoview.

Figure 3. “McGinty’s Wake.” Undated stereoview.

Figure 4. Letter published in Wid’s Daily (New York), 20 November 1921.

Figure 5. Pilot (Boston), 21 December 1918.

Figure 6. Pilot (Boston), 4 September 1920.

Figure 7. Gaelic American (New York), 19 March 1921.

Figure 8. Irish-American Advocate (New York), 22 January 1921, 8

Figure 9. Irish-American Advocate (New York), 17 March 1928.

Works Cited

Newspapers and magazines:

Billboard (New York).

Pilot (Boston).

Dubois Weekly Courier (Dubois, Pennsylvania).

Film Index (New York).

Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette (Fort Wayne, Indiana).

Gaelic American (New York).

The Irish-American (New York).

Irish-American Advocate (New York).

Irish Monthly (New York).

Irish World and American Industrial Liberator (New York).

Moving Picture World (New York).

National Hibernian (Camden, NY).

New York Clipper.

New York Times.

New York Herald.

Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California).

Optical Lantern and Kinematograph Journal (London).

Reno Evening Gazette (Reno, Nevada).

Views and Film Index (New York).

Waterloo Reporter (Waterloo, Iowa).

Wid’s Daily (New York).

Books and articles:

Barton, Ruth. 2004. Irish National Cinema. London: Routledge.

Catalog of New Films for Projection and Other Purposes. 1899. New York: F. M. Prescott. Available in A Guide to Motion Picture Catalogs by American Producers and Distributors, 1894–1908: A Microfilm Edition, Reel 1.

Complete Catalogue of Lubin’s Films. 1903. Philadelphia: S. Lubin.

Clare, M. F. 1877. From Killarney to New York; or, How Thade Became a Banker. New York: Irish National Publishing House.

Claudy, C. H. 1911. It “Went Over”. Moving Picture World (4 February): 231–2.

A Guide to Motion Picture Catalogs by American Producers and Distributors, 1894–1908: A Microfilm Edition. 1985. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Harrington, John P. 1997. The Irish Play on the New York Stage, 1874–1966. Lexington: University of Kentucky.

Heininge, Kathleen. 2009. Buffoonery in Irish Drama: Staging Twentieth-Century Post-Colonial Stereotypes. New York: Peter Lang.

Keil, Charlie. 2001. Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking 1907–13. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

McFeely, D. 2009. Between Two Worlds: Boucicault’s The Shaughraun and its New York Audience. In Irish Theatre in America: Essays on Irish Theatrical Diaspora, ed. J. P. Harrington, 54–65. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press.

Niehaus, Earl F. The Irish in New Orleans, 1800–1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965.

Orel, Gwen. 2009. Reporting the Stage Irishman. In Irish Theatre in America: Essays on Irish Theatrical Diaspora, ed. J. P. Harrington, 66–77. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Phelan, Mark. 2009. “Authentic Reproductions”: Staging the “Wild West” in Modern Irish Drama.” Theatre Journal 61, no.2 (May): 235–48.

Picture Catalogue. 1902 (November). New York: American Mutoscope and Biograph Company. Available in A Guide to Motion Picture Catalogs by American Producers and Distributors, 1894–1908: A Microfilm Edition, Reel 1.

Rockett, Kevin. 1987. The Silent Period. In Cinema and Ireland, ed. Kevin Rockett, Luke Gibbons and John Hill, 16–32. London: Croom Helm.

Williams, W. H. A. 1996. ’Twas Only An Irishman’s Dream: The Image of Ireland in American Popular Song Lyrics, 1800–1920. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

[1] For examples of other articles in the same publication on “realism” in the cinema, see 23 September 1911, 868, and 1 February 1913, 477.

[2] Such descriptions appeared in the moving picture catalogue synopses for Caught in the Undertow (USA 1902, American Mutoscope), The Prodigal Son (USA 1902, Selig Polyscope), Chariot Race (USA 1903, Lubin), and The Poachers (USA 1903, Edison).

[3] As of May 2010, a copy of European Rest Cure is available at the Library of Congress’ “American Memory” website http://memory.loc.gov.

[4] This film should not be confused with Murphy’s Wake (USA 1906, Walturdaw Co.), which was released in England in September 1906. For more information on the latter, see Optical Lantern and Kinematograph Journal, September 1906, 201.

[5] Stereoviews of this kind include The Wake (James M. Davis, 1888), By the Howly [sic] St. Patrick (Strohmeyer and Wyman, 1894), Mickie O’Hoolihan’s Wake (Strohmeyer and Wyman, 1894), McCarthy’s Wake (C. H. Graves/Universal Photo Art Company, 1897), Patrick Brannigan’s Wake (Keystone, n.d.), By the Holy St. Patrick! There’s Brannigan’s Ghost (Keystone, n.d.), and McGinty’s Wake (Canvassers, n.d.).

[6] No. 79, The Irish Blacksmith (Chicago: Selig Polyscope Company, January 1908), unpaginated; included in A Guide to Motion Picture Catalogs by American Producers and Distributors, 1894–1908, Reel 2. See also Views and Film Index, 25 January 1908, 11, which offers a synopsis of the film. An identical synopsis appears in Moving Picture World, 25 January 1908, 63–4.

[7] I base this claim on page-by-page examination of the six Irish-American newspapers named in the main text for the years 1896–1915.

[8] For Irish-American editorializing against “immoral” and “evil” stage plays, see Pilot for the following dates: 5 June 1909, 4; 8 January 1910, 4; 28 May 1910, 4; 31 December 1910, 4; 1 April 1911, 4; 8 April 1911, 4; 27 May 1911, 4; 2 September 1911, 4; 4 January 1913, 4. The Pilot published similar denunciations of dime novels (5 November 1910, 4) and comics (30 April 1910, 4).