unless a man be born again of water

John 3.5

|

In recent years, the health spa experience has become a popular and widespread social practice. The quest for bodily relaxation and wellness is permeating the needs of contemporary society, as a way of counteracting the stressful pace of city life. What is more, health spa centre designers are increasingly integrating thermal services with spaces dominated by moving-image installations, to add an extra dimension to the relaxing and revitalizing experience. As a case study, I will examine the installations of the QC Termemilano Spa & Wellness health centre.[1] In general, a spa is, of necessity, a commercial space, one designed to make money, likely to attract corporate clients and situated in a particularly affluent area of the city. A visit to this spa is quite expensive (the cost of a single entry corresponds with approximately six cinema tickets). Equally, spa-going is not a popular experience, and generally it is not a frequent habit; rather it might be reserved for a special occasion occurring once or twice a year (often for couples, as a romantic occasion). Furthermore, although my focus is upon moving images in the spa experience it must be admitted that the installations are only a small part of the spa itinerary, and they are not necessarily the determining factor in the decision to visit. They are thought to be a sort of ‘extra’ offered to the clients, as an original way of enriching the relaxation experience. Nevertheless, the case study will be examined here through the lens of film and moving-image studies and, in particular, from an aesthetic perspective, leaving socio-economic implications aside. The spa moving-image experience will be framed as a new practice for experiencing moving images and sounds. The analysis is conducted with a focus on the synaesthetic aspects of the sensory-motor and perceptual involvement of the subjects who can be considered as spectators in search of relaxing sensations in a restful environment, rather than merely as customers.

The video installations at Termemilano provide the opportunity for an analysis of two apparently opposed trends in the contemporary moving image experience. On the one hand, they signal the search for a kind of involvement based on immersion of the human body. On the other hand, they help us to reframe theatrical and relocated dimensions of the film experience. The term relocation is used by Francesco Casetti to describe the process through which a media experience is reactivated and offers itself in a different environment from where it originated, via different devices (Casetti, 2009). In the case of cinema, relocation causes the film experience to migrate from one place to another, from its “motherland” in the film theatre to new frontiers (Casetti, 2011). Today, a film can be watched in various places, in various individual and interpersonal contexts, and by means of multiple devices and screens (Friedberg 2000, 2006).

Looking closer, in fact, the relocation of cinema seems have two permutations. On the one hand, it consists of the expulsion of the film experience from the film theatre and its fragmentation into myriad viewing opportunities upon mobile and portable screens (such as the laptop, the iPhone and the urban screens). On the other hand, relocation affects contemporary audio-visual consumption practices as it extends and intensifies the sensorial and bodily side of the experience. This essay adds the water based moving image experience to relocated cinematic practices.

Termemilano spa is housed in a Liberty-style building in the Porta Romana district, one of the most affluent in the city of Milan. Termemilano is part of the QC Terme group, which includes other well-known thermal centres in the Alpine area of Italy (Bagni Vecchi and Bagni Nuovi in Bormio, and Pré-Saint-Didier in Aosta). The location of Termemilano in Milan has particular significance, for whereas the Bormio and Pré-Saint-Didier locations have terrific natural environments that offer visitors views of amazing landscapes, Milan can boast only a Spanish Garden and a huge solarium surrounded by walls built by Ferrante Gonzaga in the sixteenth century. A skyscraper looms over the garden and the noise of the traffic is always in the background. The various different types of screens, high quality installations and interesting spatial design of Termemilano might be seen as a way of compensating for the lack of naturally occurring relaxing elements. A variety of artificial multi-sensorial stimuli seek to recreate the atmosphere of natural thermal environments and provide innovative relaxing experiences. What is at stake, in fact, is not only the proliferation of ‘unconventional’ screens in the city of Milan, but the rise of new styles of moving-image spectatorship in which the spectator’s body is involved in a sense that goes beyond the merely metaphorical. The case of Termemilano shows that relocation – which at first seems to imply a weakening of the involving potential of moving-images – can be combined with immersive conditions of vision.

In the following I shall retrace the Termemilano relaxation itinerary and analyse a number of audio-visual installations, arranged so as to alternate with pools and saunas. The wellness itinerary begins with the immersion in the indoor pools in the basement and continues with the return to the first floor and a long passage, along which are laid out the relaxation rooms, each of which is dedicated to a particular natural element (water, fire, earth or air). The spa-goers meet a first screen in the Sala Aqua. The passage brings them to the buffet hall, where spa-goers can enjoy fruit, cereals and herbal teas. The itinerary continues outdoors in the garden, with hydro-mineral pools and a huge solarium. After the immersion in real water, the spa-goers move on to the final place of the itinerary[2], where they can experience immersion in water in a very special way: the ‘Teatro delle Meraviglie’ [Wonders Theatre], a spacious room which incorporates a series of moving-image installations. These installations offer a kind of experience that extends the interaction with actual, physical water that the spa-goers have during their immersion in pools, to a kind of experience in which the body is not physically but synaesthetically immersed in water. The video’s subject is, in all the cases, a non-narrative representation of water (mostly the waving motion of water). This gives origin to an experience that is not merely a metaphor of image and sound as a flux of water, but rather, of something that is bodily perceived. The spa-goers’ body is not materially in the water, but because they perceive sensations this gives them the kinaesthetic sensation of being enveloped and immersed.

As the description of the wellness itinerary at Termemilano will show, my case study is very different from the ‘proper’ moving-image experience in a number of psychological, spatial and economic aspects and must not be confused with the former. More akin to video art installations in a museum (though, as discussed above, occurring in a commercial rather than artistic context), the Termemilano installations are non-narrative pieces that offer composite and unusual sensorial experiences and share some of the features of contemporary amusements such as imax, theme park rides and highly illusionistic museum installations, i.e. the spectacular and enveloping nature of both the screen and the images. Nonetheless, the Termemilano moving-image experience also has a number of points in common with the theatrical film experience,[3] namely the psychological dynamic between absorption and immersion; the dark, large and bordered environment in which it takes place and the pseudo-social condition in which a group of people have an experience individually. At the same time, it helps us to focus on some of the traits of the relocated film experience as an annex, an extra added to other experiences, that takes place in a space that is not a movie theatre, and which implies a kind of gaze that not does necessarily have to be constantly focused on the screen.

A crucial component of my argument will be the debate between different theoretical accounts of the tendency first, of film to immerse the beholder and second, of the beholder to ‘dive or be absorbed in’ the film. In the light of the framework of this bidirectional dynamic, I will argue that the spa moving-image experience helps us to reframe both the theatrical and relocated dimensions of the contemporary film experience.

Absorption/Immersion

There is a deep connection between water and the moving-image, which has the intrinsically aquatic nature of a flow of visual stimuli through a virtual three-dimensional space. Images and sounds stream on the screen like an inexhaustible flow of water, with a mechanical fluidity that perfectly expresses the spirit of modern times. The relation between filmic water and the city dwellers’ body has been a subject of early cinema, which turned the ancient rite of the spa into the modern custom of going to the swimming pool. One of the first Italian films is I bagni di Diana (1896; known also as Les Bains à Milan, Bains de Diane, or Les bains de Diane à Milan), shot by Lumière operator Giuseppe Filippi. The 45-second film shows people diving from three boards set at different heights in the public baths called Bagno Diana in Milan (the first Italian public swimming pool). As some people watch from along the pool’s edge, others dive into the pool, using a variety of different styles. The film premiered on 12 July 1896 at the Grand Café in Boulevard de Capucines, Paris. An additional note to the program of those projections informs us of an extremely interesting event: the last two reels – La démolition d’un mur and Bains à Milan – “seront passés a l’envers”, will be projected in reverse motion (see Rittaud-Hutinet 1985, 39). This trick added to the spectacular motion of the diving bodies and the splashes of water an estranging and funny effect. The bodies re-emerge from water and move against the laws of gravity.[4] The trick reveals the mechanical nature of cinematic fluidity.

Other examples from the silent era are Sutro Baths, Sutro Baths, No. 1, and Lurline Baths, three actualities produced for the Edison Manufacturing Company by James White and Frederick Blechynden in 1897. The films are set in two swimming pools in San Francisco. Albeit with some differences, all three films depict bathers descending from the slipway. The swarming crowd in the pool creates splashes of water up towards the camera. These sensorial stimulations are linked with the specificity of the cinematic medium, through being intended for projection in the theatre space. “Instead of producing a mere attraction, the formal qualities of these films insist on the materiality of moving pictures that has to do with a particularly 1897 understanding of and attention to projection” (Daniel 2010, 21). Indeed,

we discover a creative impulse in this group [of actualities], one that insists on performing what the medium can do in order to urge creative intervention from its viewers instead of trying to render it transparent in order to immerse the spectator in a diegetic world (Daniel 2010, 21, my emphasis).

Rendering transparent the illusive machine of cinema and immersing the spectator in the diegetic world were, conversely, the main aims of Hollywood classical narrative cinema. The term immersion here gains a precise, limited and metaphorical meaning in relation to the nature of the world in which the spectator is immersed, i.e. a diegetic meaning. It is as if the classic spectator immerses his/her head and witnesses the fictional story from the edge of the swimming pool (the screen) – a kind of immersion in which the beholder, as it were, stays dry. The term absorption seems to fit better with cinema’s tendency to offer “the feeling that while watching a film, ‘you are there’, while simultaneously producing the acknowledgment that ‘you cannot be there’” (Rushton 2009, 50, emphasis in original), such is the classic description of illusion, as the real experience of a fictional world while maintaining the awareness of its fictional nature. Nevertheless, not only does the beholder seek a ‘risk-free’ and illusive involvement in the diegesis, but also as Rushton puts it the “mode of viewing in the classical cinema is … one which establishes a tense dialectic between the spectator’s seeking of the film, that is, the spectator’s absorptive pull into the film, and the film’s seeking of the spectator, the film’s attempt to ‘present’ itself to the spectator” (Rushton 2004, 234, emphasis in original). In a more recent article, Rushton (2009) calls the two poles of this dynamic absorption and immersion. In the absorptive mode, the spectator “is drawn into” or “goes into” the film, whereas in the mode of immersion, “the film comes out to the spectator so as to surround and envelop her/him” (Rushton 2009, 49, emphasis in original).

In the classical age of cinema, however, absorption/immersion remains a disembodied dynamic. It is only from the 1970s onwards that the advent of new expressive styles and new technologies leads to a film experience that is strongly based on a more physical involvement and a less metaphorical and disembodied absorption. Today early cinema’s original tendency to offer acrobatic and spectacular events to attract and astonish the audience has been dramatically superseded. The movie theatre is neither a crowded bath with splashes, as in early cinema, nor a marvellous aquarium that confines the spectator to appreciating fine specimens at a distance; rather, it is a huge pool, an ocean bed, a swampy marsh or a limpid bay in which spectators experience a sense of being engulfed and dragged toward the waterfall of perception, or getting sucked into a whirlpool of emotion. Contemporary mainstream narrative cinema engages the spectator in a physically demanding experience, an experience packed with thrilling chases and explosive crashes, impulsive acts and natural disasters, falling and fighting bodies. Therefore the film experience has progressively become embodied, in the sense that it engages not only the eyes of spectators, but their bodies as well, through a wide assortment of stimulations that range from eliciting neurophysiological reactions to cognitive-based emotions (see D’Aloia 2009, 2011).

The same can be said of the embodying potential of sound. As Richard Maltby (2003) argues, the first major technological innovation of post-classical Hollywood cinema was the improvement in the quality of sound. As a consequence, according to Michèle Lagny (2004, 259),

[t]he audience can literally be ‘hit’ with sound, experiencing the movie with a far greater degree of physical involvement than was previously possible. As the soundtrack has become more intricate, more complex, and straightforwardly louder, the audience has become less a participant in the performance, and more simply an auditor. The movie theatre has become less of a space of social interaction and more of a three-dimensional extension of the screen’s two-dimensional image in which the audience is surrounded by sound.

In this kind of immersive cinema, as suggested by Robert Stam (2000, 317-318), “The spectator is ‘in’ the image rather than confronted by it. Sensation predominates over narrative and sound over image, while verisimilitude is no longer a goal; rather, it is the technology-dependent production of vertiginous, prosthetic delirium.”

Here, again, immersion might be a contradictory and misleading term. The idea that the film comes out of the screen and surrounds the beholder “has become a very popular mode of contemporary theorizing, whether one is writing of expanded cinema, new media, high-octane blockbuster cinema, horror or ‘body genre’ cinema” (Rushton 2009, 50). In a book examining the skills that spectators deploy when relating to spectacular and immersive architectural structures, large-scale illusionistic media, and interactive modes of exhibition, Oliver Grau (2003, 13) states that “Immersion is undoubtedly key to any understanding of the development of the media, even though the concept appears somewhat opaque and contradictory.” Immersion offers observers “the option of fusing with the image medium, which affects sensory impressions and awareness” (Grau 2003, 13, my emphasis). In most cases, immersion is “mentally absorbing and a process, a change, a passage from one mental state to another … characterized by diminishing critical distance to what is shown and increasing emotional involvement in what is happening” (Grau 2003, 13). What is at stake in these discussions of immersion is the opposition between sensory and cognitive, between mental absorption and intellectual activity, between emotional involvement and critical distance.

Today, the dynamic absorption/immersion is more radical than its classical significance. It is no coincidence that the main response of theatrical cinema to the displacement and impoverishment of the film experience (due to the process of relocation) has been to offer an experience that is more comfortable in a very physical sense and, above all, to search for new and enhanced forms of immersion, refining its spatial environments, technical means and special effects. The intention is to give the spectator both the impression of really being in the space of the fictional events depicted (absorption) and an intense sensorial experience (immersion). The representation of water on screen seems to offer a useful perspective for understanding this radicalization. In contemporary mainstream narrative cinema, many films embody aquatic modes of expression and perception, even if water is not explicitly used as a subject or a setting, this observation helps us to understand the connection between experiencing real water in the spa pools and experiencing ‘visual/aural water’ in video installations. These narrative films tend to ‘enwater’ the spectators, i.e. embody them in water, in an immersive and fluid experience (see D’Aloia, 2010).

In order to go beyond the absorption/immersion dichotomy, I propose a description of the relationship between spa-goers and the moving-image that is based on the idea that both the skin and the screen are ‘osmotic surfaces’ that continually and mutually exchange a substance; this substance, i.e. water, constitutes a common experiential environment, a space in which the subject sensorially, synaesthetically and imaginatively experiences the deep, dense sense of water symbolism.

Osmotic surfaces

A crucial point for my argument is the key role that pre-cognitive and pre-linguistic knowledge play for the moving-image experience. This kind of experience is grounded in the empathetic capability of the body to feel the concepts expressed by a work of art or a communicative object and to grasp them directly, rather than trying to understand them through a series of deliberate inferences. Viewers explore the surface of the screen, with no recourse to cultural background or cognitive activity. Only after this immediate approach to the expressive forces of moving images do spectators dive into the depths and call on their socio-cultural knowledge and background skills in order to interpret the meaning. Moreover, the surface of the water inevitably refers to the surface of the cinematic screen. Water makes the screen a fluid and interconnecting threshold between two places, between here and there, between presence and absence, the conscious and the unconscious, waking and sleeping. Just as the screen both separates and brings together the fictional and the real worlds, water is also a plane of separation and connection between two different but not incompatible worlds.

The very first accounts of empathy were based on the idea that this type of immediate comprehension of the world was possible because of an intrinsic analogy between the internal nature of the human body and the nature of the outside world. According to Empedocles, all matter is comprised of four roots, or elements. Knowledge originates in the encounter between an element within a human being and the same element outside of him/her: ‘For with earth do we see earth, with water, water, with air bright air, with fire consuming fire, with Love do we see Love, Strife with dread Strife’ (Empedocles, B 109). This osmosis between internal and external substances suggests the naïve idea that immersion in an environment, e.g. water, is a kind of experience whose significance is founded on co-substantiality, the sharing and mutual exchange of common characteristics. As we know from physiology, the human body is about 60% water for adult males and 55% for adult females. Ideally, immersion in water means merging water into water, a return to the natural substance of life.

This empathetic understanding of the world is grounded in the osmotic flow that merges internal and external waters. In terms of our case study, both the features of the space in which moving-image installations are located and the aesthetic features of their non-narrative images and sounds affect our basic layers of sensory and perceptual experience and do not require the subjects to perform any demanding motor or cognitive activities. Of significance in this regard is the experience of relaxing in the Sala Acqua (Fig. 1) one of the four rooms in the Termemilano relaxation area. Spa-goers can lie on their backs on water beds and observe the undulating light-blue images projected onto a screen that covers the entire surface of the ceiling. The salty tang of the sea wafts up from a diffuser and the gentle lapping of waves filters in through a sound system. Alongside the other elements detailed above, the slow, liquid movement of the images and the suffused light they radiate, the breadth of the projected surface, the relaxing sounds, the pleasant smells and the comfortable posture give the spa-goer a full-immersion experience. This is achieved by projecting the expressive properties of water outside the space of the screen and by using multi-sensory stimulations that literally and metaphorically construct a water-based environment, a place to share an experience in which spectators can feel fully involved. Even when not actually immersed in material water, spa-goers’ bodies experience the water synaesthetically and imaginatively, remembering what the water felt like and, more or less consciously, recalling its symbolic meanings.

Figure 1: The ‘Sala Acqua’ at Termemilano

Prior to exploring this aspect, I want to clarify that the particular kind of empathy I am referring to does not affect the relationship with other subjects, given the non-narrative nature of the images. Whereas the mode of absorption and the ideal act of entering the film hold forth “the possibility of being another being” (Rushton 2009, 50, emphasis in original), i.e. the film character, “with immersion comes the sensation that the film is entering your own space, perhaps even that it is entering your own body” (Rushton 2009, 50, emphasis in original). In contrast to absorption, immersion only offers the “option of remaining firmly within the bounds of one’s own selfhood”, “a refusal of ecstasy, a denial of the possibility of becoming other” (Rushton 2009, 53). Spa moving-image installations ask the spa-goers to tune in to their own body (and even lose awareness of it), in a kind of (hedonistic and individualistic) empathy that could be termed auto-empathy.

Synaesthetic anaesthesia

Empedocles’ ideas were further developed by Aristotle to assert that the elements all arise from the interplay between the archetypal properties of hotness and coldness, dryness and wetness. Water, for example, is wet and cold and its qualities are fluidity and flexibility, which make it able to adapt to external conditions (Aristotle, 1998). As a consequence, water tends to be expansive, to fill spaces in its surroundings. In De Anima, Aristotle divides the senses into two categories: the senses of touch and taste that apprehend their objects by direct contact, and the distance senses – sight, hearing and smell – which approach their objects without immediate contact. The objects of sight are perceptible through media. The medium of sight is composed of simple elements, e.g. air and water. The power of sight must be realised in an organ made of a transparent liquid, for it to be receptive of colour and light (Aristotle 1993, III: 1).

The idea that the transparency of water allows sight to pass through space and reach its object suggests an analogy between the transparency of water and the act of vision. Contemporary theories of immersion also start from the primacy of the gaze. Virtual realities, for example, “seal off the observer hermetically from external visual impressions … expand perspective of real space into illusion space … install an artificial world that render the image space a totality or at least fill the observer’s entire field of vision … integrate the observer in a 360° space of illusion, or immersion, with unity of time and place … offer a completely alternative reality” (Grau 2003, 13). Nevertheless, “[t]he most ambitious project [of virtual reality] intends to appeal not only to the eyes but to all other senses so that the impression arises of being completely in an artificial world” (Grau 2003, 14). This essay addresses the senses through the use of interfaces that combine simulated stereophonic sound, tactile and haptic impressions with thermoreceptive and even kinaesthetic sensations.

Water on the screen seems naturally to embody this immersive multi-sensorial aptitude as well. “Diving into water … or sinking into a bath, we are not only in the realm of the audio-visual sensorium; all our senses, in fact all of our body, is encapsulated, surrounded. In that sense, it is a haptic experience, not merely an optical one” (Holmberg 2003, 132, emphasis in original). Whereas during the wellness itinerary at Termemilano, all the five senses are actually involved (I can feel the warmth of the water on my skin, I can drink the herbal tea, I can smell the hydro-mineral water, I can hear the splash of the jets, and so on), the moving-image installations activate synaesthetic perception. As bodily stimulation is crucial for a relaxing experience, the senses of sight, hearing, taste and smell round off an experience that is based on the sense of touch over the entire surface of the body – the skin – and connected to proprioceptive perception.

From a phenomenological perspective, synaesthetic immersion and personal experience seem to be strictly linked. The experience of touching or immersing oneself in water is inseparable from the experience of being touched by water. By means of this ‘double sensation’ (the experience of sensing oneself being touched), the touched hand can sense that it is being touched, as in the famous example of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty (Merleau-Ponty 1962, 93). As Vivian Sobchack would argue in the wake of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s notion of reversibility (Merleau-Ponty 1968, 139), the spectator is both a seeing and seen subject (Sobchack 1992, 103-104), involved in both the act of perceiving and the act of perceiving his or her perceiving.

Nevertheless, the return to a synaesthetic experience of water for the spa-goers, after it has been actually experienced, suggests that the spa moving-image experience is different in many ways from the cinematic (viewing and hearing) experience that Sobchack discusses. The spa moving-image experience has its own distinctive characteristics in terms of the particular sensorial involvement it offers. Once in the Teatro delle Meraviglie, Termemilano spa-goers are invited to assume a comfortable position (reclining on a hammock, lying down on a waterbed or on a body pillow, on their own or with their partner) and to relax with the help of images and sound. To complete the multi-sensorial stimulation, the salty tang of the sea wafts up from diffusers.

One of the installations in the Theatre, called Il nido [The nest], consists of a looped projection onto the wall of a video of a school of fishes in deep tropical water (Fig. 2) The undulating flow of the fishes creates a movement that involves the spa-goer in a relaxing (almost hypnotic) experience. In front of the screen is placed a white plastic alcove with a waterbed. The alcove is shaped like a jellyfish, evoking the experience of a bed resting on the sea bed. The viewer reclines on the bed in the alcove and relaxes to the movement of the fine specimens.

|

|

Figure 2: The installation Il nido in the Teatro delle Meraviglie at Termemilano |

These images are relaxing because the bodily stimulation consists of a sort of synaesthetic anaesthesia, achieved through a multi-sensorial bath and a complete immersion into synaesthetic water, which has an ability to lighten the body and ease its movements. Paradoxically (given the prominence of moving images to this experience), in order to achieve full relaxation, the spa-goer must close his/her eyes.

With Eyes Wide Closed

Actual immersion in water corresponds to a return to the security of the womb. Every spectator has a primordial sense of liquidity or fluidity and has an (unconscious) memory of the in-utero state. The fullest manifestation of anaesthesia is sleep. A new world of perception gapes in front of the sleeper’s eyes: the dream. In Freudian psychoanalysis, the presence of water in dreams refers to the in-utero state: “A large number of dreams, which are frequently full of anxiety, and whose content often involves … being in water for a long time, are based upon phantasies concerning the intra-uterine life, the sojourn in the mother’s womb” (Freud 1913, 250). Immersion in water also takes us back to birth: “Dreams of this sort are parturition dreams; their interpretation is effected by reversing the fact recorded in the manifest dream-content; thus, instead of ‘flinging oneself into the water’, read ‘coming out of the water’ – that is, ‘being born’” (Freud 1913, 250).

As Carl G. Jung stated, in dreams and fantasies, the sea, or any large expanse of water, is the commonest symbol for the unconscious, the “deep valley of the psyche” (Jung 1959, 17-18). The way of the soul in search of something or someone that has been lost “leads to the water, to the dark mirror that reposes at its bottom” (Jung 1959, 17); “the treasure lies in the depths of the water” (Jung 1959, 24). Nonetheless, “This water is no figure of speech, but a living symbol of the dark psyche” (Jung 1959, 17). The living nature of the symbol of water suggested by Jung allows us to clarify that the use of water in the moving-image – conceived as the concrete and perceivable projection of an inner projection of the psyche – is not intended merely as a film setting, nor as a mere aesthetic solution to express the internal state of the character. Water is a substance capable of communicating symbols and meanings to the spectator directly, reducing the separation between the fictional space on the screen and the psychic space in front of the screen.

Inspired by both Jungian archetypes and his interest in alchemy, Gaston Bachelard pointed out, in his study on the “imaginary waters” in poetry and literature, that water ranges from the clear, slow moving, innocent and transparent river, (see Bachelard 1983, 33), to the deep, heavy and running waters that symbolise the passing of time and death (see Bachelard 1983, 46). Bachelard argued that human imagination does not draw on interpretation but rather is supported by “direct images of matter” (Bachelard 1983, 8), images in which “the form is deeply sunk in a substance” (see Bachelard 1994, ix). Daydreaming (rêverie) sends waves of the unreal into reality and allows the daydreamer to reach the sleeping waters within themselves. The sensorial and sensuous experience of matter, memory and imagination find expression in poetic imagery based on water: “A poet who begins with a mirror must end with the water of a fountain if he wants to present a complete poetic experience” (Bachelard, 1983, 21-22, emphasis in original). This experience takes place in physical spaces in which human beings dwell, physical spaces that themselves influence human memories, feelings and thoughts. Inner and outer space – the mind and the world – are reciprocally implicated (see Bachelard 1994, 201). If we include the film theatre in the space of poetic experience, we may approach the water-based moving-image experience as an immersion of the material imagination. Even more so, in the spa moving-image experience, the absence of material water recalls the vast symbolic imaginary of water and stimulates the imagination.

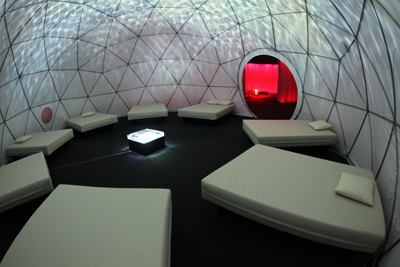

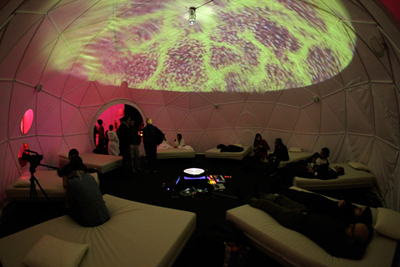

The Magic Dome

The apotheosis of this kind of empathetic multi-sensorial immersion experience is represented by an installation that has been set up in the Teatro delle Meraviglie in 2011. The so-called Magic Dome was designed by Ronald Lewis Facchinetti (in collaboration with Andrea Modica and Mattia Trabucchi) of Kilohertz, an Italian company that creates multi-sensory installations and media environments for use in special environments at hotels, clubs, lounge rooms, cafes and trade shows and that are especially suited to relaxation areas at spas. The Magic Dome consists of a 30-foot-diameter dome, with eight waterbeds beneath. In the middle of the dome a circular water container is placed on a black cube inside which a subwoofer produces the sound. From the top of the dome, a video beam projects a coloured stream of light on the container. The vibration produced by the music (with its dominant low frequencies) generates micro-movements in both the water in the container and on the beds. The movement of water is in turn reflected on the parabolic surface of the dome, creating a kaleidoscopic visual effect of abstract shapes (Figs. 3 and 4).[5]

|

|

|

Figure 3 and 4: The Magic Dome at Termemilano |

|

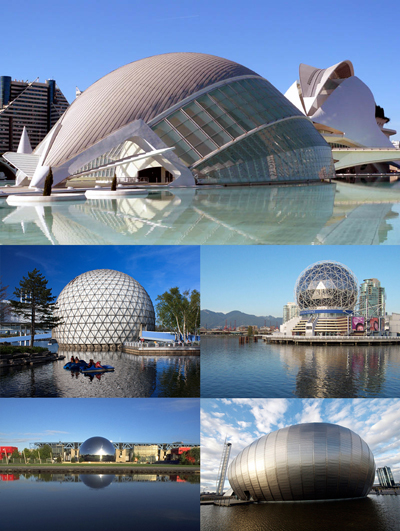

The dome surface inevitably refers to relatively new trends in cinema screen and movie-theatre design, dating from the 1980s. The geodesic or hemispheric architectural structure of an omnimax (i.e. imax Dome) offers a fully immersive and enveloping experience, re-evoking the attractional tendency of early cinema, which was aimed at engendering physical involvement by astonishing the spectator.[6] Nevertheless, as Heide Hagebölling (2004, 13, emphasis in original) writes, “Immersive cinematic experiences in the form of panorama or dome projections can be seen as predecessors of … experiments with virtual environments”. These experiences “presuppose an appropriate architecture or special projection technologies and images of films produced specifically for them [and] are representative for this development of illusionist cinematic experiences” (Hagebölling 2004, 13). As far as we are concerned, it is no coincidence that many of these buildings look like spheres or seashells and are located on a waterfront or near rivers or artificial lakes (e.g. La Géode at Parc de la Villette in Paris, the cinema at Telus World of Science in Vancouver, the cinema in the Parc du Futuroscope in Poitiers) or even partially submerged (e.g. L’Hemisfèric at La Ciudad de las Artes y de las Ciencias in Valencia, the Ontario Place Cinesphere in Toronto or the cinema at the Glasgow Science Centre) (Fig. 5).

|

Figure 5: from top, clockwise: Spherical imax and geodesic cinemas in Valencia, Vancouver, Glasgow, Paris, and Toronto |

The aim of such mammoth theatres and giant screens is to render the great spectacle of nature. They represent a surfeit of realism, with the aim of seducing the spectators and offering them a special experience (as befits their settings in science museums or amusement parks).

What looks like a floating structure from the outside looks like an underwater one from the inside. As if in a sort of capsule for underwater exploration, viewers are deluged by a flood of images. Unsurprisingly, omnimax and imax shows very often include 3D films with water-based settings (e.g. Sea Monsters by Sean MacLeod Phillips for the National Geographic, USA 2007; Dolphins and Whales: Tribes of the Ocean by Jean-Jacques Mantello, USA/Bahamas 2008 Under the Sea by Howard Hall, USA/CAN 2009; Wild Ocean by Luke Cresswell and Steve McNicholas, USA 2009, to cite some of the most recent seasons only), whose properties clearly present an opportunity for a spectacular immersive experience. As Lagny (2004, 151, my trans.) writes in an article on circular and spherical cinema in France,

the giant screen, and its spherical incarnation in particular … was created as a prosthesis of real space, in order to thoroughly stimulate the senses usually engaged by film, namely sight and hearing, and to accentuate the impression of movement. The intention is to create a kind of total cinema that envelops the viewer, but the kinaesthetic effects it produces, in terms of physical sensations … are often considered key success factors in their own right.

Changes in the shape of the theatre and the screen also affect the spectators’ experience. Lagny’s article is an extremely useful aid to understanding (partially as a counterexample) the psycho-physical involvement of spa-goers at the Magic Dome. As she explains, due to the enveloping screen and surround sound “the frame disintegrates and their gaze penetrates the image itself, right to the heart of the action”(Lagny 2004, 156). Changes in the mode of perception engender an uncomfortable sensation in the spectator, with the loss of the reference points of the traditional cinematic view and the system of orientation used in everyday life, in which the senses of touch and smell cooperate with the eye and the ear in immediately reconstructing the space. At this point, Lagny (2004, 156, my trans.) puts forward the notion of vection:

It is known that a moving visual scene may in fact induce a sensation of bodily movement in a motionless observer, which may be referred to as ‘vection’. This ‘vection’ can be a source of conflict between the data from the visual receptors that create the illusion of movement, and that from the vestibular, proprioceptive and tactile receptors located in the inner ear. This conflict creates postural disturbances (falling), which are sometimes combined with psychosomatic reactions that occur as dizziness or nausea … It is as if there were a conflict between amplified auditory and visual data, on the one hand, and other (incapacitated) senses, on the other: the loss of balance is somehow a form of revolt on the part of the inner ear, which is subjected to an exercise of the most unusual kind.

This sense of imbalance is primarily a result of the off-screen space ceasing to exist and becoming entirely incorporated in the geodesic screen, which covers the viewer’s entire field of view and constitutes a completely continuous surrounding surface. As Philippe Jaulmes (1981, p. 38) has stated, the spectator “tends to be alone in the presence of an image that represents his/her perception”; an effect of ‘subjective perception’ is achieved. The screen merges into and literally corresponds with the architectural space of the theatre, which becomes a sort of swimming pool. In the ‘geodesic cinema’, the theatre and the film, “the material and the immaterial”, become inseparable (Virilio 1986, 35-39, my trans.).

The spectator is thus involved in a demanding activity. In order to solve the vection conflict and re-orientate the perception, he/she has to perform a rebalancing through the activation of cognitive compensation. As Laurent Jullier (1997, 83, my trans.) noted in relation to the new cinema screen, “[r]ather than present itself as a space for building, or rebuilding, instead the film space becomes a space to be explored, to be visited”, demanding of the spectator the effort of continually reconstituting distorted images and localizing sounds. Immersion is an insidious challenge for the senses. If we look again to both ancient and modern thought, we find that Plato (1993, 66a) pointed out, in Phaedo, that a straight stick appears bent when dipped into water. The problem is to recognise and distinguish reality from the distorted images of what is not reality. And as Freud himself remembers, referring to Aristotle, “the best interpreter of dreams is he who can best grasp similarities. For dream-pictures, like pictures in water, are disfigured by the motion (of the water), so that he hits the target best who is able to recognise the true picture in the distorted one” (Freud 1913, 71).

Also at the Magic Dome, liberated from the constraints of the traditional cinematic orientation of the body and the social rules that impose a standard posture, spa-goers can literally explore the space with their bodies and senses. Nevertheless, they are not disoriented and overstimulated, but rather are invited to enjoy the sense of bodily immersion and perceptual ‘dispersion’; they are involved in a relaxing moving-image experience with their senses. They are not required to perform demanding motor or cognitive activities, but rather to abandon themselves to the gentle swaying of the water. This is possible, of course, because of the abstract and non-narrative nature of the images and sounds, which are intimately connected to the essence of nature and are designed to achieve the empathetic purpose of merging the external movement of images and sounds and the internally (affectively and bodily) perceived movement. In so-called dynamic cinema (which can be experienced in omnimax theatres in amusement parks), the body is subject to the physical movement of both the space and the seats, which combine with the movements depicted on the screen. At the Futuroscope in Poitiers, for example, there are rows of seats that move synchronically with the film and panorama projections that include the ceiling and floor. Conversely, in the case of the Magic Dome at Termemilano, the mutually reinforcing movements are intended to create a sense of relaxation through a sort of harmonic synchronization between the undulating motion of the images and sounds and a visceral sense of swaying. As when underwater, gravity feels less intense and spa-goers can explore the screen without the need either to understand what is happening on it or to be exposed to a storm of emotions or sense of dizziness.

Sound Waves and the Inner Ear

Sound has a crucial role to play in the construction of the regressive (back to the womb), immersive and synaesthetic experience. The ‘sound environment’ specifically designed by Mattia Trabucchi and Massimiliano Biancardi for the Magic Dome is called Influence of Waves and aims to create a fully immersive and relaxing experience. Technically speaking, it is designed for four audio channels, one subwoofer and two transducer files. One of the tracks is called Glockentrip.[7] The work is a blend of generative composition and dubbing techniques. Sounds are abstract, the structure is minimal and a hypnotic rhythm has been created to fade out the outside world. The composition is based on the deconstruction of the triad that defines the harmonic design, with the aim of creating a potentially infinite melody, using the minimum possible number of harmonic tensions. This goal is achieved through the integration of audio-visual and tactile effects, modulated by a single source (Figures 6 and 7).

|

|

Figure 6 and 7: DJ set on the occasion of the Magic Dome inauguration

The concept behind the Magic Dome is closely related to a synaesthetic and tactile experience of images and sounds. The music is conceived not to be in the ears but in the body, which becomes a sort of third ear, an inner ear that is not subject to a conflict of balance, but rather experiences the pleasure of being suspended and floating. The geodesic structure is used to immerse the sentient body, transporting it into a space that is not only visual, but also aural and kinaesthetic. Whereas the sonorization in hemispheric cinemas aims to disorientate and stun the spectators by overwhelming them with stimuli (see Lagny 2004, 152), in the Magic Dome they are wrapped up by the screen and invited to relax in a soothing, fluid sound environment.

As Marshall McLuhan (1972, 456) argued, acoustic space is a space “that has no centre or no margins, unlike strictly visual space, which is an extension and intensification of the eye. Acoustic space is organic and integral, perceived through the simultaneous interplay of all the senses; whereas ‘rational’ or pictorial space is uniform, sequential and continuous and creates a closed world.”[8] The spa-goer’s body offers a space for listening, where sound creates shapes that can be visualized within the dome. The analogous relation between the bodily sensations experienced by the spa-goer through the perception of the movement of water in the beds. The audio-visual sensations created by the liquid image generator on the dome’s surface and the sound environments are different forms of the same, isomorphic, undulating and relaxing movement (a sort of ‘hydro-audio-visual massage’). This formal analogy between sound waves, visual waves and fluctuating tactile sensations has its basis in water. Water functions as the catalyst, bringing vibrations to the body as its refracting light rays produce visual effects. Sound is tuned to one’s own internal bodily sensations. The subject dips into a watery, virtual space and experiences being touched by the sounds and images that seem to be produced by his/her own body.

Re-Emergence

Moving-image installations in Termemilano Spa are a significant example of the integration of audio-visual media into the context of contemporary social practices. Although no material water is present, these installations use the expressive properties of water (such as fluidity, transparency and depth) and its inherent symbolic ‘aquatic’ meanings in order to provide the spa-goers with a ‘multi-sensorial sensation’ of complete immersion. Many of the features of this particular moving-image experience are symptomatic of the general immersive trend of audio-visual experiences, even though, as we have seen in regard to the absorption/immersion debate, the term immersion has several meanings and can even be ambiguous.

The search for immersion derives from the need to be completely surrounded by an intangible yet experienceable substance and to feel fully engulfed and enveloped in a comfortable environment. The spa moving-image experience is a literal metaphorical example of immersion that recalls some of the traits of the contemporary theatrical film experience. Like the movie theatre, health spa centres offer protective, safe spaces detached from the real, troubled world. In this sense, the relationship between architectural space and sensorial or psycho-physical space is crucial, since it is functional in creating a space of experience in which the subjects are bodily involved (e.g. in the extreme case of omnimax). Nevertheless, unlike in contemporary cinema, the enhancement of the sensorial dimension does not aim to shock or bombard the senses, rather the aim is to anaesthetize them. The spa experience offers an opportunity for city dwellers to temporarily abandon the frantic pace of urban living (especially at Termemilano, with its city centre location), to dissolve the cares of their everyday life and let their bodies relax. Moreover, in contrast to intellectual videoart gallery experiences or the empathetic involvement with the film character that is typical of narrative cinema, no interpretation or demanding cognitive activity is required of the spa moving-image-goers. Further, in comparison to geodesic theatres, no attempt is made to restore their axes of perception, instead, they are abandoned to the lapping motion of the water.

Most interesting for film and media scholars is the way in which the spa moving-image experience could be also seen as a response to the practice of locating screens outside film theatres and the consequent loss of immersivity. Outside the film theatre or the videoart gallery, the Sala Aqua and the Teatro delle Meraviglie (in particular the Magic Dome) at Termemilano offer a dislocated (or relocated) immersive moving-image experience. The spa moving-image experience is a response to the threat of the loss of disembodied empathy, typical of classical cinema illusion based on mental absorbing, with a new kind of embodied (auto-) empathy based on bodily immersion.

References

Aristotle, 1993. De anima. Translated from Greek by D. W. Hamlyn. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Aristotle, 1998. Aristotle’s Metaphysics. Translated from Greek by H. Lawson-Tancred. New York: Penguin.

Bachelard, G., 1983. Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter. Translated from French [1942] by E. Farrell and F. Farrell. Dallas: Pegasus Foundation.

Bachelard, G., 1994. The Poetics of Space. Translated from French [1958] by Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press.

Casetti, F., 2008. The Last Supper in Piazza della Scala. Cinèma & Cie, 11, pp. 7-14.

Casetti, F., 2009. The Filmic Experience. Screen, 50(1), pp. 56-66.

Casetti, F., 2011. Back to the Motherland: The film Theatre in the Postmedia Age. Screen, 52(1), pp. 1-12.

Daniel, J. A., 2010. The Participatory Potential of Early Cinema: A Reexamination of Early Projected Films. M.A. University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign.

D’Aloia, A., 2009. Caduta libera. Forme empatiche di esperienza filmica della città. Comunicazioni Sociali on-line, 1, pp. 130-144.

D’Aloia, A., 2010. Cinematic Enwaterment. Drowning Bodies in the Contemporary Film Experience. Comunicazioni Sociali on-line, 3, pp. 31-39.

D’Aloia, A., 2011. Cinematic Empathies. Spectator Involvement in the Film Experience. In: D. Reynolds, M. Reason, eds. Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural Practices, Bristol: Intellect.

Darroch, M., 2009. Interdisciplinary Vocabularies at the University of Toronto’s Culture and Communications seminar, 1953-1955. Communication at ‘Media in Transition 6’, MIT (24-26 April 2009), [online] Available at: <http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/mit6/papers/Darroch.pdf> [Accessed 15 June 2011].

De Vries, L., 1971. Victorian Inventions. London: John Murray.

Freud, S., 1913. The Interpretation of Dreams. 3rd ed. Translated from German [1900] by A. A. Brill. New York: Macmillan.

Friedberg, A., 2000. The End of Cinema: Multimedia and Technological Change. In: C. Gledhill and L. Williams, eds. Reinventing Film Studies. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 438-452.

Friedberg, A., 2006. The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Grau, O., 2003. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge, MA, London: MIT Press.

Hagebölling, H., 2004. Interactive Dramaturgies: New Approaches in Multimedia Content and Design, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Holmberg, J., 2003. Ideals of Immersion in Early Cinema. Cinémas, 14(1), pp. 129-147.

Jaulmes, P., 1981. L’écran total pour un cinéma sphérique. Paris: L’Herminier.

Jullier, L., 1997. L’écran post-moderne. Un cinéma de l’allusion et du feu d’artifice. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Jullier, L., 2002. Cinéma et cognition. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Jung, C.G., 1959. The Collected Works. Volume 9, Part 1: The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated from German [1934-1954] by R.F.C. Hull. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Lagny, M., 2004. Muoversi con l’immagine: il senso dell’equilibrio. Bianco e Nero, 548, pp. 148-159. French translation: Tenir debout dans l’image: le sens de l’équilibre. In: A. Autelitano, V. Innocenti and V. Re, eds. 2005. I cinque sensi del cinema: XI convegno internazionale di studi sul cinema / The Five Senses of Cinema : XI International Film Studies Conference (Udine-Gorizia, 15-18 marzo 2004). Udine: Forum, pp. 187-199.

Maltby, R., 2003. Hollywood Cinema: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

McLuhan, M., 1972. The Playboy Interview: Marshall McLuhan. A Candid Conversation with the High Priest of Popcult and Metaphysician of Media. By Eric Norden [Playboy Magazine, 16(3), 1969]. In: The Storm Before the Calm. Chicago Playboy Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M., 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. Translation from French [1945] by Colin Smith. London, New York: Routledge.

Merleau-Ponty, 1968. The Visible and the Invisible. Translated from French [1964] by Alphonso Lingis. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, 2004. The World of Perception. Translated from French [2002] by Oliver Davis. New York: Routledge

Michaux, E., 1999. Du panorama pictural au cinéma circulaire. Origines et histoire d’un autre cinéma, 1785-1998. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Peseux, V., 2004. La Projection grand spectacle, du Cinérama à l’omnimax. Paris: Dujarric.

Plato, 1993. Phaedo. Translated from Greek by David Gallop. Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press.

Rittaud-Hutinet, G., 1985. Le cinéma des origines: les frères Lumière et leurs opérateurs. Champ Vallon: Seyssel.

Rushton, R., 2004. Early, Classical and Modern Cinema: Absorption and Theatricality. Screen, 45(3), pp. 226-244.

Rushton, R., 2009. Deleuzian Spectatorship. Screen, 50(1), pp. 45-53.

Sobchack, V., 1992. The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of the Film Experience. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stam, R., 2000. Film Theory: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Virilio, P., 1986. L’opération de la cataracte. Cahiers du cinéma, 386, pp. 35-39.

[1] The author would like to thank Alessandro Bolis, Renato Cheodarci and Luca Mancinelli of QC Terme for their collaboration.

[2] Spa-goers can, of course, vary the order of the various activities, but spatial consequentiality implicitly suggests a ‘natural’ sequence.

[3] It is interesting to note the use of the words ‘wonders’ and ‘theatre’ in the name of the space. Indeed, this experience reminds both the ‘attractive’ nature and some of the spatial and technical features of the film-theatre experience. As at the entrance of old film theatres, heavy curtains do not allow light to penetrate the room, and the projector beam cuts through the darkness and illuminates the walls, the floor and the ceiling, transforming them into screen surfaces.

[4] A similar trick can be found in Bathers (Cecil M. Hepworth, 1900), where, through reverse motion, human bodies dive into and seemingly come out of the water.

[5] A video showing the audio and visual effects of the installations is available at: <http://flavors.me/mattafunk#7d3/vimeo> [Accessed 10 April 2011].

[6] Immersivity and panoramic projection have been linked since the origins of the cinema (the Panorama was in fact used in photography and painting before it was in cinema). For a historical overview and technical description of wide screens and panoramic film formats, see Michaux, 1999, and Peseux, 2004. It is interesting to add a note on the Mareorama, an example of motor and multi-sensorial simulated experience that could be conceived as a precursor of the immersive cinematic experience. Invented by the minor realist painter Hugo d’Alesi and presented at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900, the Mareorama was a simulated sea voyage in which the combination of moving marine panoramic paintings and a large moving platform gave the spectator the sense of being on the rolling and pitching deck of a steamship. The illusion of a sea voyage was enriched by an ocean breeze created by fans, lightning flash effects, the sounds of a ship’s propeller and the steam siren, and the smell of seaweed and tar (see De Vries, 1971).

[7] The track is available at: <http://soundcloud.com/mattafunk/glockentrip-influence-of-waves> [Accessed 10 April 2011].

[8] On the theoretical framework of acoustic space and the influence of Le Corbusier (‘visual acoustics’), E. A. Bott (‘auditory space’), T. S. Eliot (‘auditory imagination’) and L. Moholy-Nagy (‘vision in motion’) on McLuhan’s work, see Darroch 2009, pp. 12-16.