|

Introduction

Why do we sit so close [to the screen]? Maybe it was because we wanted to receive the images first. When they were still new, still fresh.

Michael Pitt in The Dreamers (2003)

In Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, a character describes his cinephilia as an indolent, almost submissive absorption of images, eyes glued to the screen as he sits ensconced in the darkness of a cinema auditorium “to receive the images first”. There is a sense of capitulation: Susan Sontag (1996) writes of “the experience of surrender to, of being transported by, what was on the screen. You wanted to be kidnapped by the movie … to be overwhelmed by the physical presence of the image.” (emphasis added) Roland Barthes (1989, 345) writes of leaving the movie theatre as one “coming out of hypnosis”—“there exists a ‘cinematic condition’ and this condition is prehypnotic”—with all the connotations of a hypnotized subject’s helplessness and relinquishment of control. To these writers, watching movies becomes a submissive, almost compliant act.

Nevertheless, romantic as it sounds, the film spectator never abdicates agency but, rather, is always actively engaged with the movie in various sensorial and cognitive ways (Casetti, 2009 and 2011). Peter Lunenfeld (2004, 383) writes of interacting with the film’s hypercontext, “something far more interesting than backstory and more complicated than synergistic marketing” – “a rhizomatic and dynamic interlinked comunicative community using networks to curate a series of shifting contexts”. Technology further enables additional ways of interacting with a filmic text. For example, videotapes, DVDs and Blu-Ray allow the viewer to examine the film in various speeds, repetitions (Mulvey, 2006), and degrees of minutiae. With respect to DVDs and Blu-Ray, the viewer is also able to access ancillary material to the film in the extras typically bundled with a disc, including behind-the-scenes and making-of footage, bleepers, games, and even alternative endings. Far from being merely a passive receiver of images, the film viewer outside the movie theatre has a variety of ways to view and interact with the filmic text.

However, such interactions do not affect the narrative structure of the film, which essentially remains intact. While the film spectator has some control over what is displayed on her screen and how it is played, she has none over the film text itself. Even if a DVD extra offers the possibility of playing an alternative ending, that ending exists as a discrete video clip rather than an integral part of the film. The filmgoer cannot do anything to actively change the story. Indeed, as Grahame Weinbren (1995a) argues, “the impossibility of impacting on the cinematic is one of the sources of our pleasure in it: should Lila Crane in Psycho be able to heed our cries of ‘don’t go up(/down) the stairs’ and turn back, the entire effect of the horror film would dissolve. Much of cinema’s power over us is our lack of power over it, and, in this sense, suspense is a paradigm of cinematic response.”

To that extent, interactive cinema upends this viewing paradigm by specifically allowing its audience to have some power over it. This is usually achieved by having the audience participate in some way to affect the film’s narrative, such as voting to decide the fate for a protagonist at a crucial moment. The crux lies in the film simply not being able to continue without the audience’s intervention. Here, the term interactive has to be made more specific. We can interact with a film as an experience and as a medium, but interactive cinema involves the ability (or, at least, so perceived) to intervene and change the images to produce an alternatively meaningful text and to have that text reflected back to us. Espen J. Aarseth (1997, 48) defines interactive in the sense of “an interactive work” being one “where the reader can physically change the discourse in a way that is interpretable and produces meaning within the discourse itself.”[1] Essentially, there is some sense of a capacity to alter the text in consequential ways with nontrivial effort, such as choice, discernment and decision-making.[2] The spectator’s interaction with interactive cinema thus takes on a different note. Her input now goes beyond the usual sensorial and cognitive engagement to include activities of consequential effort such as singing, voting or, in the case of an online interactive film, clicking on a particular link. More importantly, her interaction is integral to how the film narrative proceeds and, in turn, how the film is shaped and therefore engaged with.

This article examines a spectator’s cinematic experience in interactive cinema with these ideas of interactivity in mind. Much of the literature on interactive cinema so far discusses the effects on narrative structure (Hales, 2002 and 2005). Yet, interactive cinema also presents intriguing questions in terms of film engagement, which have to date not been discussed in depth. How does an audience relate to a film whose progress requires its active participation? How does the format change the sense of time and agency in watching a film? Moreover, interactive cinema has yet to be considered in the light of digital technologies, where the modalities of the personal computer and Internet surfing afford different screen attachments to online interactive cinema. What different experiences does the presentation of an interactive film on the Internet solicit? How might its presentation of hyperlinks, text, sound and images affect its levels of interactivity? I explore these questions by discussing the film engagements of two representative interactive films, Kinoautomat : One Man and His House (1967) and Sufferrosa (2010). The rationale for selecting these two films is to compare the experiences of two kinds of interactive cinema: (i) as exhibited in a hall; and (ii) as shown online. In the process, I make two arguments: firstly, that engaging with interactive films staged in front of an audience involves unique temporalities and degrees of immersion and agencies, factors which result in a mode of film engagement akin to gaming that incorporates limited agency within a controlled situation; and secondly, that watching online interactive films removes the limitations of the staged event, creating instead a viewing experience of chance, whose significance is not so much in the images as in the motivated yet random movements of the computer mouse. I finally argue that, in these ways, the viewer forms new attachments to the image which extend to various reflections on the nature of flux, chance and choice in viewing moving images.

Push the Button: Interactive Cinema and Kinoautomat

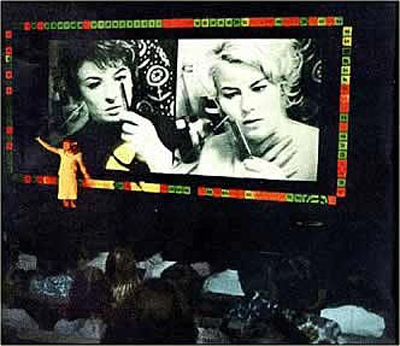

In 1967, Czech filmmaker Radúz Činčera exhibited Kinoautomat: One Man and His House at the Montreal Expo. Billed as “the world’s first interactive movie”, the film is about a “hapless Mr Novak who finds himself caught up in various situations which represent moral dilemmas” (Naimark, 1998). Screened in a specially constructed cinema, the 124 audience members in the theatre each had a red and green button on their seats. At various points,[3] the film would stop and two moderators would walk onstage to introduce a choice in the plot for the audience (for example, one scene was “whether to let in a scantily-clad female neighbor right before his wife was due home”) (Naimark, 1998). The audience would vote for either plot choice by pressing one of the two buttons, and the scene carrying the majority vote would be played by the projectionist.

Kinoautomat caused a worldwide sensation and people queued daily at the Expo to see it. Its appeal is understandable: there is a certain frisson in having some power over how a film plays out. Since then, there have been numerous variations on Kinoautomat. For example, Chris Hale’s staging of his interactive film show Cause and Effect includes films such as Natural History (2003), which requires the audience to hum together in order to refocus an image, and a similarly-themed Crescendo (2003), in which the audience works together as a group “by singing a sustained high note—something that any one individual would not be able to do for long enough” (Hales, 2005, 61). His earlier touch‑screen installation project, Jinx (1996), requires the gallery visitor to click on, or touch, “hot spot” items in a man’s flat so as to trigger off a gag while the man rushes around his apartment preparing for a job interview. Pia Tikka’s interactive film project, Obsession (2003), creates what she calls “a manuscape”—“an embodied interactive zone, a cognitive and conceptual landscape”—which allows a participant to have control over the film’s story via “both conscious actions and unconscious sensorimotor reactions of the participant’s mind/body”: “Participants’ spatial moves and acts, as well as their densities in space, are tracked and translated into symbolic parameters that modify the narrative and its intensity” (2004, 16-17). In Grahame Weinbren’s installations, Kreutzer Sonata (1991) and The Erl King (1983-86), the user’s interactions change the “temporal conglomerate of images and sounds” (Weinbren, 1995a).[4] For example, in Sonata, the viewer is able to control the flow of narration, playing it out either as a flashback or as a recounting of events, depending on whether she points left or right at the screen. By pointing up and down, she can add additional narrative layers, such as a character’s fevered imaginings, or external references such as “the classical image of Judith with the severed head of Holofernes” (Cameron, 1995).

The commonality in all these works is that they require some form of participation from the viewer in order to proceed, or to be completed. Kinoautomat cannot be played in its entirety without the audience’s votes. Interactivity becomes part of the film—it is a feature, a constituent. As Weinbren (1995b, 407) puts it: “Interactivity is like an additional property added to the cinema: along with images and sounds, viewer impact becomes an element of the montage”.

How does this affect the way we relate to cinema? How does interactivity change our screen attachments? I consider three issues. The first is time. I argue that the temporality of interactive cinema differs from its non-interactive counterpart, effectively resulting in a different media form. The temporality of non‑interactive cinema points to pastness. This is so in two ways. Firstly, its narrative refers to the past; its events have already taken place. By recounting those events, the narrative is thus closed; it shuts out everything else which did not happen. That closure relegates all events into the past—it happened like this. Secondly, the ontology of the recorded moving image is of pastness. Its premise is the fact of something which has happened (and was recorded) previously so that we may, in a future time, re‑view it as an image. The logic of the production of the image necessarily entails a prior event: a photograph or film can only be made from something that was, or happened, before the viewing of that photograph or film. Roland Barthes expresses precisely this temporality of the recorded image as the object “having-been-there”: “[the photograph] establishes not a consciousness of the being-there of the thing (which any copy could provoke) but an awareness of its having-been-there.” To Barthes, the inherent pastness of the photograph is so powerful that he nominates its quality of “having-been-there” as its “reality”, “for in every photograph there is the always stupefying evidence of this is how it was, giving us, by a precious miracle, a reality from which we are sheltered (emphasis in original)” (1977, 44). Our relation with non-interactive cinema is therefore always present in the temporal latency of its pastness—its “having-been-there”-ness—unrolling before us in the presentness of our viewing it.

However, interactive cinema occupies a different kind of time. It is reliant on the viewer taking a particular action in the present. In the presentness of those actions, interactivity confers uniqueness, for that moment of interaction only happens once, even if everything else—the viewing hall, the audience, the projected film etc.—remains the same. As Richard Schechner (2002, 288) explains, “even though every ‘thing’ is exactly the same, each event in which the ‘thing’ participates is different. In other words, the uniqueness of an event is not in its materiality but in its interactivity” (emphasis added). In that uniqueness, interactivity always remains in the now. It cannot be repeated. It cannot be exchanged. It cannot be reproduced. It cannot be saved. It cannot be recorded. The temporality of pastness in non-interactive cinema is derived from the relationship between the photographic image and reality in terms of a physical trace (of light reflecting off the object onto a light-sensitive surface) and in the closed nature of its narrative. As a result, the way we interact with and relate to the images of interactive cinema becomes fundamentally different—not in their pastness (of contiguity between image and object in the Baudrillardian sense of l’ecriture de la lumiere), but to participate in a certain experience in the present, where the narrative is flung wide open and the image leads not to the pastness of what had gone on before but to the futurity of what outcome might emerge from it. While the projected images of interactive cinema do, of course, play before us as referents pointing to traces of past objects in a past time, the necessity of action with those images in the viewing of interactive cinema expands that relationship, so that they also become elements of a wider arrangement which points to an immediate present moment. In enjoying a different temporal relationship with its images (past versus present), the fundamental nature of interactive cinema qua cinema changes. In short, Kinoautomat becomes a hybrid media form between cinema—in the projections of a reel of recorded images—and live performance, where, with each moment (of decision) writ large in the construction of narrative, the singularity of an interactive film screening takes on significance, with different narratives, combinations and event paths on every occasion. Extending from that, might such singularity point towards a different way of looking at interactive cinema as cultural reproduction, one which encompasses its here and now, rather than the mechanical screening of projected images? In its emphasis on the decisive moment, Kinoautomat may even put paid to Gotthold Lessing’s (1962) idea of the suggestive moment in art, whereby the reproduced moment is literally opened up to spectatorial imagination and action. Extrapolating from this, the moment in interactive cinema can thus be distinguished from the frozen static moment (photography, sculpture) and from the assembly of moments into movement (cinema) (Charney, 1998). In interactive cinema the moment becomes a potentiality, a point of becoming, hovering at the cusp of action that will tilt that moment into its futurity.

The second of three issues to consider is immersion. As a basic definition, immersion refers to the degree to which an individual feels absorbed by or engrossed in a particular experience (Wittmer and Singer, 1998). Laurie N. Taylor (2002, 12) argues for two forms of immersion: (i) diegetic immersion, in the way of becoming “lost” in a good book, remaining “unaware of the creation and relation of the elements within the text”; and (ii) situated immersion, or intra-diegetic immersion, where, in the context of video games, “the player is immersed in playing the game and in the experience of the game space as a spatial and narrated space”. The former is typically achieved in non-interactive cinema. There are numerous theses on diegetic immersion in film studies research, particularly from various cognitive perspectives, ranging from how emotions are elicited through film narrative, music, editing screen shots (Plantinga and Smith, 1999), to how the spectator identifies with and responds to film characters (Plantinga, 2009).

However, situated immersion rarely, if at all, applies to non-interactive cinema. As Taylor (2002, 12) points out, involving the spectator in the space of the diegesis is “a primarily figural notion—a conceit of narrative convention”. The spectator simply does not participate in any way in the diegetic space of the film. But this is not the case with interactive cinema. By putting the spectator in control of the film’s narrative, be it prescribing a mode of action for the protagonist or purporting to break a glass in the film by sustaining a high note for an unusually long duration, the spectator is effectively engaged in the world of the film by being made to act within it, rather than on it. The spectator’s engagement with the film in interactive cinema is thus also different in this sense: she is situationally (if perhaps also diegetically) immersed in a way she is not for non-interactive cinema. Andrew Cameron (1995b) makes the same point, albeit in a different framework, by differentiating between diegetic and situational immersion as the imperfective and the perfective (respectively, inside and outside the time being represented):

I suggest that interactive representation is imperfective—that it throws the spectator inside the time being represented, giving rise to a high degree of identification within the text, whereas linear narrative is perfective—events in time are represented as completed and are viewed from the outside.

In the process, achieving intra-diegetic immersion in interactive cinema blurs the line between diegetic and non-diegetic space for the viewer, and fundamentally changes the entity of the film itself. By the situational immersion achieved in interactive cinema, the spectator relates to the film not simply as a text which exists behind the screen, but also as an extension of her physical space. The boundaries of the film text are no longer distinct, for the spectator is purportedly able to affect the film from her actions in her non-diegetic space. By achieving situational immersion, the text of the interactive film is not confined merely to the images on the screen, but also extends to the space and reality of the spectator as well as, if in a collective viewing, the shared spaces and realities of the audience. This also complicates the interactions of looks within and without the filmic process. Generally speaking, the spectator watches a character in a film as an invisible subject (Mulvey, 1975; Willemen, 1994), where “the visible is entirely on the side of the screen” (Metz, 1975, 304ff). However, the immersion of interactive cinema changes this monocular perspective. By situationally immersing the spectator into the film, she is now not only a participant of the diegetic space but her psychology is also co-opted into an exchange of intra-diegetic looks with the character, one which is particularly significant in the spectator’s potential to change the narrative path of that diegesis. The film text is no longer a discrete object, but mingles with the action, psychology, gaze and perspective of the spectator.

The third and final issue to consider is agency. In ostensibly being able to affect the narrative by her actions, the viewer becomes an active author of the filmic text. In the process, she fulfils a creative participatory force, becoming at least partially responsible for the diegetic world, bleeding the realities of her actions (voting or singing) into the realities of the filmic world (Mr Novak jumps to his death or the glass breaks). This clearly does not happen in non-interactive cinema. The purported loss of autonomy of the filmmaker in directing the narrative correspondingly feeds to the spectator’s agency in her authorial role, blurring the lines between viewing, participation and control. As Malcolm Le Grice (1995) writes:

Interactivity replaces the concept of the passive viewer by the active participant. The experience of being a protagonist, whilst still operating in a symbolic field, is more direct in interactive systems than in the traditional forms of identification which operate in cinema. An interactive cinema needs to offer a fundamental range of choices to the user in interacting with the work. This cannot be confined to a few alternative linear routes, endings or character view-points in an otherwise linear narrative structure (emphasis added).

In other words, an interactive work, in order to be meaningful, has to provide substantial and realistic options for the spectator to interact with the film. Le Grice eschews the offering of “a few alternative linear routes” (the modus operandi of Kinoautomat); his own work, rather, involves physical movements as the mode of interaction to decide narrative form, direction and shape. Nevertheless, what is important is that there has to be a real sense of an audience’s capabilities as the decider of events in the film or the shaper of the work, and some amount of non-trivial effort involved in interacting with the work.

What might be the consequences of this? On an implicit level, the framework of the film’s operation changes: surrendering such authorial control to the viewer shifts a model of totalitarian oversight to a mode that is more collaborative and accountable, even consultative. In this way, the ethos of interactive film also reflects the larger digital media culture of collaboration and crowdsourcing (Tryon, 2009; Rheingold, 2002), and, in turn, possibly a larger political and cultural stance that contains democracy, liberty and accountability, even empowerment (Rokeby, 1995, 147). The irony of Kinoautomat as a work from then-socialist Czechoslovakia ceding control of its narrative to democratic voting cannot be missed; Chris Hales (2005, 56) also describes the film as “an ironic dig at the democracy that was so evidently lacking in Communist-controlled Czechoslovakia at that time”. In that sense, this mode of interactive cinema can thus be read as an implicit promise of a political promise which Andrew Cameron (1995b) characterises as “the politics of interactivity”:

If the politics of a change in representation is centred on the move away from narrative with its baggage of authority, certainty and closure, the politics of interactivity at a more general level are about the end of mass culture. Interactive television or video telephony promises profound transformations in cultural and political life by fundamentally reordering the communications infrastructure away from a broadcast architecture in favour of a fully distributed network like that of the telephone system. Interactive infrastructure seems to promise liberation from authoritarian political control (emphasis added).

Yet, is the spectator really in charge? Or might the authorial role have been overstated? We discover that the implications of democracy in Kinoautomat, for example, is also accompanied by farce, as Michael Naimark (1998), one of the few reporters who visited Prague to meet the filmmaker, reveals:

Činčera [in talking to Naimark about Kinoautomat] went on to say that the beginning of every newly selected scene was a close-up of Mr. Novak saying ‘You’ve made an excellent choice. I’m not just saying this. I do this every day and you really did make an excellent choice’.

The ironies of Mr Novak’s statement work on a number of levels. Mr Novak obviously does not do this “every day”; he did it once, maybe a few times, for the shot. The pre-recorded line similarly cannot possibly refer to the actual choice made by the audience, so the acclaim completely (and deliberately) misses its mark. The humour thus lies in the misalignment between Mr Novak’s compliment and the situation in which that compliment was given. Add to that the mathematical subtleties of Kinoautomat and the truth of how the film is really played out: given five opportunities each with a 50-50 chance of taking one of two choices, the film theoretically has a possibility of 32 endings and 32 routes to its ending.[5] However, Kinoautomat had only one ending, with the scenarios developed in such a way that two possibilities would recombine to form exactly the same situation, from which two more options would be offered to the audience, and this would repeat 5 times throughout the film (Naimark, 1998). As Brenda Laurel (1993, 53) puts it, “it is rumored that all roads led to Rome—that is, all paths through the movie led to the same ending”. Nor did the film magically play the elected scene: the scenes were, instead, toggled between two projectors, one comprising red possibilities and the other green, with a shutter that simply covered one or the other projector according to the vote. In view of all this, Mr Novak’s compliment is deeply ironic: the audience has not made an excellent choice, just as Mr Novak does not judge spectators’ choices every day. In fact, when seen in terms of the bigger picture (there was only ever one ending), the audience never even had a choice at all: the destination was always going to be Rome.

All this points to a rather more qualified role for the autonomy and agency of the spectator: she is not in charge despite the implicit promise of interactivity, entrusting some amount of control to the viewer; arguably, she is, rather, a victim of a rigged situation. Yet, there is the undisputed fact of the audience’s role in the film. To the limited extent of being able to choose a green or red button, to sing or not to sing and so on, the spectator does retain some element of choice. Perhaps a more appropriate framework, then, is to see interactive cinema as a game, rather than a position in which the authority of the author is distributed to the audience. The framework of a game, by way of making decisions and actions within the restrictions of an overarching setting (Jones, 2008), may thus be more accurate. While there may only have been one ending, there are 32 ways to get to that ending, and every one of those ways requires at least some element of an audience’s action before it can be embarked on. Similarly, in a game, the narrative is both open and closed—the rules of the game bind the player to an already established narrative, yet it is still open in terms of how that narrative is told and employed. Engagement with interactive cinema may therefore be more akin to gaming—taking actions within a restricted framework, maneuvering against its constraints, chancing with a narrative that is simultaneously written and undecided.

This is not to say that interactive cinema shifts the medium entirely from film to game, for, insofar as cinema is concerned, the images and narrative worked through within those images are still very much part of the experience and medium. Yet, there is some amount of blurring of those boundaries, whereby interactivity confers an element of gaming—to the extent of acting within a constrained framework—in the experience of watching interactive cinema. The convergence of media in interactive cinema lies in the straddling between imagery and interactivity. In that sense, it is perhaps more accurate to see interactive cinema also as a combination of several media forms between performance, cinema and games.

Move the Mouse: Chance and Sufferrosa

We love the tangible, the confirmation, the palpable, the real, the visible, the concrete, the known, the seen, the vivid, the visual, the social, the embedded, the emotional laden, the salient, the stereotypical, the moving, the theatrical, the romanced, the cosmetic, the official, the scholarly-sounding verbiage (bullshit), the pompous Gaussian economist, the mathematicized crap, the pomp, the Academie Française, Harvard Business School, the Nobel Prize, dark business suits with white shirts and Ferragamo ties, the moving discourse, and the lurid. Most of all we favor the narrated.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb (2003, 132)

Taleb’s “Black Swan” Theory examines that which falls beyond “the narrated”: the unpredictable (or at least hard to predict), unexpected and undirected event that nevertheless greatly affects the development of science, history and art. The theory revolves around the notion of chance. The oldest known reference to the term “black swan” is Juvenal’s phrase, “rara avis in terris nigroque simillima cygno” (“a rare bird in the lands, and very like a black swan” (Morris, 1982, 451)), which is ultimately a comment on probability: it is so rare for a swan to be black that the very vision of it becomes a metaphor for a chance bordering on the impossible.

Yet, chance matters at every turn in interactive cinema. By virtue of the probability which accompanies each interactive act (to vote red or green; to sing or not to sing), there is always an element of contingency. However, the role of chance becomes greater in certain forms of interactive cinema. I argue that chance in viewing online interactive cinema (when stored, presented and shown on the Internet) is so dominant it becomes its main mode of engagement. I take as my tutor text the non‑linear, web-based interactive film, Sufferrosa (http://www.sufferrosa.com/) (See Fig. 1) by multi-media artist Dawid Marcinokowski.

Described by an online review as “an interactive, narrative project combining photography, film, music and web”, this review also calls its aesthetics “a multidimensional, audiovisual collage referring to Jean Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965)” (quietearth 2010). Since its inception, Sufferrosa has been presented at several film festivals and exhibitions (such as the Geneva International Film Festival, OFFF Post-Digital Culture Festival, MOVES International Film Festival, WRO Media Art Biennale) and has been critically acclaimed (The Guardian describes it as “cutting-edge interactive Polish detective noir” (Rose 2011); Jawbone.tv praises it as “[b]y all cinematic measures…a standout”: “It’s beautifully shot, simply designed, cleverly written and cheekily intriguing. Like a Depeche Mode video covered in honey.” (Denis 2010) The prologue of this “(neo‑noir) interactive movie” outlines its plot, whose starting point is that the protagonist, Detective Ivan Johnson, is looking for a missing woman. His investigations lead him to Professor Carlos von Braun, who we later realise operates a clinic which administers a dodgy anti-aging treatment called Rejuvenation. In his pursuits of the missing woman, Detective Johnson is drugged and taken to Professor von Braun’s clinic on Miranda Island. The rest of the film is interactive as the viewer encounters the motley characters on Miranda Island—shadowy treatment patients, their spouses, murderous women intent on killing von Braun etc.—and learns about their stories and motives by clicking various links which appear in the screening space of the film. As the film’s introduction states: “What happens in the movie depends entirely on the viewer’s choice.”

|

Figure 1: The starting page of Sufferrosa |

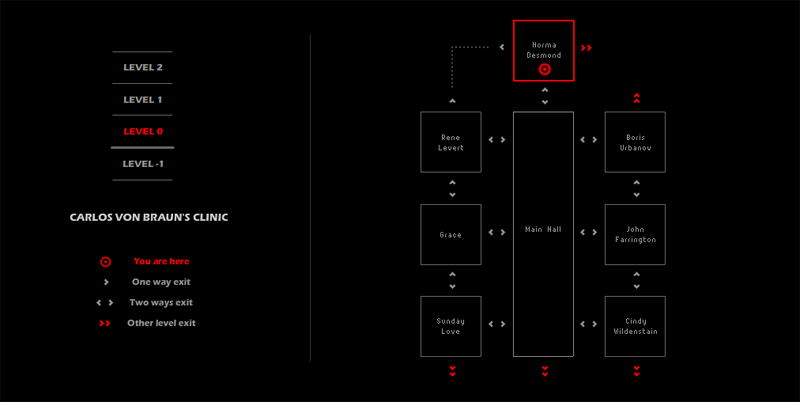

While beautiful in itself—it has been reviewed as “a gorgeous piece of art; every second of it is stunning and worth framing a print” (Tate, 2010)—Sufferrosa’s raison d’être remains the interactivity it affords by way of its online presentation and exhibition. This interactivity operates on a number of levels. Firstly, the spectator may choose to view a wide variety of images and film clips by clicking on various relevant links which would appear when the mouse is moved over them. The film’s “About” page cites “110 scenes”; “3 alternative endings”; and “20 different locations”, all of which may be accessed in a variety of routes through 4 “clusters” of live links, labelled Levels -1, 0, 1 and 2 respectively. Secondly, the viewer may also obtain additional information about characters and sub-narratives presented inside text boxes by moving her mouse over designated icons. Thirdly, by clicking the relevant link, the viewer may “exit” the narrative of the film at any time to be shown a “map of the clinic” (see Fig. 2), namely a diagram outlining the route of links which the viewer has taken and could take. This gives a “meta” view of the interactivity of the work, and is thus interesting not only in deconstructing the film’s very ontology (of sequencing links), but also in laying bare its interactive narrative, showing in stark terms just how the viewer has affected the narrative of the film she has been watching thus far.

|

|

Figure 2: The map of the clinic |

However, most interesting of all is the role of chance in Sufferrosa, writ much larger than in non-online interactive cinema. Chance plays a major part in Sufferrosa via three features of the work, all of which concertedly engage the viewer’s random movements of the mouse (in other words, by the movements and choices of the viewer selecting constantly (even if she selects not to click and just to hover the cursor over the link)). The first feature is that the choices are presented as live links scattered across the screen space of the film, which is an irregularly-shaped area illuminated against a black background.

|

Figure 3: The screen space of Sufferrosa |

The links pop up only when the viewer moves her mouse over them (Fig. 4):

|

Figure 4: Pop-up links in Sufferrosa |

This creates a different viewing experience from non‑online interactive cinema shown in movie theatres such as Kinoautomat, which clearly presents a stark choice to the audience: the red button or the green button. The audience has to choose. However, in Sufferrosa, it is more a case of discovering the choices rather than making them. The key experience in Sufferrosa is thus not so much in the choosing but in the exploring which lies behind moving the computer mouse, for the viewer does not know where the links are, and can only uncover them when the mouse is finally moved over a relevant area of the screen so that the links pop up and become visible, hitherto concealed as in a minefield. Secondly, there is no way of going “back” to a previous option. Clicking the Back button on the viewer’s web browser returns the viewer to the film’s homepage; she would have to “enter the movie” and start all over again. The only way to navigate and proceed with the film is by constantly moving the mouse across the screen to uncover live links. Thirdly, although a whole area of the screen might be dedicated to one link (for example, “Carlos von Braun’s Chronicle”), where the mouse is clicked in that area also makes a difference to the images to be viewed. Effectively, clicking different areas of even the same link present different images. The film experience of Sufferrosa is thus of constant exploration and discovery not only of the screen space concealing the links, but also of the different links in different areas of that screen space. In view of screen engagement, in these ways Sufferrosa also involves notable provisional sensibilities to the film experience tied to this virtual tactility of the screen: moving the mouse around in this exploratory manner, we roam the screen as if with our hands, and certainly with our eyes. While not directly haptic, touch is nevertheless engaged in terms of the mouse-controlling hand’s reflexes, dexterity and skill in finding and establishing mouse positions. Hand and eyes become closely coordinated in a feedback loop between hand/eye/movement/registration and the screen, where this loop indicates if there are any links available for selection. The result is a contextual awareness of and attachment to the screen’s constant translations of thought to action, light to movement, and hyperlink to decision.

The experience of viewing Sufferrosa is thus not so much about authorial control (despite the film’s slick promise—“what happens in the movie depends entirely on the viewer’s choice”) or of pursuing a collectively decided narrative. Rather, it is about the random discovery of links by constantly roaming and exploring the film’s screen display of hidden hyperlinked text and images. I finally argue that this randomness is a significant constituent of Sufferrosa’s viewing experience. Engagement with the film becomes dependent on chance and accident, as compared to following a narrative in non-interactive cinema or to the more pro-active gaming model—straddling between constraint and control—of non‑online interactive cinema. The motivated yet random moving of the mouse to navigate Sufferrosa is an exercise of the accidental in its haphazard chancing upon links, depending on how the mouse wanders. Yet, even in the randomness of its movements, there is also an objective, for the mouse is moving with the intention of discovering links. Experiencing Sufferrosa becomes a sort of contradiction—an aimless quest, a motivated wandering—in its being simultaneously accidental, yet purposeful. In this contradiction, engaging with Sufferrosa—the core of which lies in moving the mouse—is more about the happening of its being (unearthing the links which will lead to the continuation of the film and clicking on them) than about pursuing any sort of specific mission, such as following a linear narrative or making choices.

What, then, might this form of engagement with Sufferrosa signify? Malcolm Le Grice (1995) writes of narrative form as “a representational model”, “a tool by which human beings grasp and structure their understanding of the world”. To that end, I also see the form of Sufferrosa in its modus operandi of chance and randomness as a plangent echo of how we might perhaps understand the world today. For example, postmodernism confers a suspicion of objectivity and/or any form of meta‑narratives; the indeterminacy of reality in the postmodern world is thus also premised on chance, subject to variable circumstances of time, space, culture, linguistics etc. The wave mechanics of quantum physics, as another example, similarly debunk the predictability of physical properties as a description of the underlying nature of our physical realities. Instead, particles are seen to be a probability on the wave-function—the position of a particle in a wave packet is to be described only via the probability amplitude of its position and momentum, yet those are properties whose singular values can never be measured simultaneously with precision, for the more precise the position measurement, the less precise the momentum measurement becomes, and vice versa (as stated by the Heisenberg uncertainty principle).[6]

Viewing Sufferrosa thus involves a different understanding of the world and mode of engagement from those of other forms of interactive cinema. It partakes in a context of flux, such that each encounter with the film is about the ephemera of discovery, whose probabilities of success change every microsecond as the mouse rolls. Grahame Weinbren (1995) charges that interactivity in multimedia tends to “involve trivial ‘point and click’ actions” on the part of the user, signifying an “elevation of interface over content and meaning”, and thus evidencing “a product of software dominating narrative form”. However, I contend that Sufferrosa’s interactivity goes deeper than that, even though the user ostensibly does not do much beyond “‘point and click actions”. Instead, it becomes a metaphor for a larger idea: an expression and awareness of a less linearly accumulated knowledge and a less formulated set of aesthetic and structural values. The mouse becomes the muse, pondering in its own trundling movements an alternative form of discovery and being. In so doing, the temporality of the moving image shifts to the future: my fingers which move the mouse (or, for that matter, manipulate a fingerpad) point to a futurity—the becoming of the narrative as the links pop into existence, opening doors and gateways through which we learn the fortunes of the film’s characters, the intertwining of fingers, futures and fates in the randomness which makes up the basis of Sufferrosa.

Yet, even as my fingers manipulate the computer mouse to uncover more links, the implicit promise of freedom, potential and discovery in its random movements remains qualified by the overarching control of its technology. The work is, after all, created, displayed, operated and exhibited by the computer and its accessories; above all, the viewing experience is shaped by them. All media operations are dependent on their respective media platforms, but the politics of interactivity—its ideology of freedom, choice and empowerment (remember Sufferrosa’s assuring line, “What happens in the movie depends entirely on the viewer’s choice”)—renders interactive cinema ever more ironic. To that extent, the invisible control of technology is also a part of the experience of viewing Sufferrosa, where the fingers handling the computer mouse morph into the controlling grasp of technology, and the film’s futures and its characters’ fates interwoven with the mass of circuits, optics, electrical wires and materials science that bring them to the viewer for the pleasures of her choosing an option so manipulated it was perhaps never even hers to begin with.

Conclusion

I have discussed the engagements of interactive cinema both in terms of a staged performance and an online medium. In both discussions, I have also implicitly compared them to screen engagements formed with respect to non-interactive cinema. For a staged interactive film (such as Kinoautomat), it is viewed in the presentness of a performance, whose temporality is different from the pastness imparted by a work based solely on recorded images. Further, the audience achieves situated immersion through interactivity with its perceived abilities to affect the diegetic narrative. Finally, engagement with the interactive film takes on a mode akin to gaming, where the viewer is like a player with limited agency in a context of rules and restraints. For online interactive cinema (as discussed specifically with respect to Sufferrosa), the role of chance shifts the engagement of the film to one of aleatoric discovery. In turn, the temporality of the film shifts to the future, as the viewer experiences the film primarily in terms of uncovering its links, pointing to what might be led to rather than what led to it. These different engagements of cinema may also give rise to other issues. For example, how might interactivity affect cinephilia and the fundamental act of admiring and loving the image? How might we think about the medium of cinema itself, as interactivity changes its fundamental premises of technology and ontology? How may we contextualise interactive cinema, particularly as it exists online, in terms of media convergence and the wider digital mediascape? Those questions are beyond the scope of this article and will have to be taken up in further research. For now, though, with Kinoautomat and Sufferrosa at least, our fingers rest on their respective buttons, deciding fates and selecting paths in the narrow confines of control we have in a reeling world.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I wish to thank Jim Barrett for the numerous conversations we have had from which stem many of my thoughts in this article, and for bringing Sufferrosato my attention in the first place. I also wish to thank Catherine Fowler, Paola Voci and my two anonymous peer reviewers, as well as friends and colleagues at HUMlab, Umeå University, Sweden, and at CRASSH, University of Cambridge, UK, particularly Coppelie Cocq, Mike Frangos, Tim Hutchings, Astrid Mager and Andrew Webber, for their comments and feedback on this article. Finally, I am grateful to The Kempe Foundation, The Newton Trust and The Leverhulme Trust for awarding me funding and thus time to write. All errors and omissions remain mine.

References

Aarseth, E., 1997. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Barthes R., 1977. Rhetoric of the Image. In: Stephen Heath, ed. and trans. 1977. Image-Music-Text. London: Fontana Press, pp. 32-51.

Barthes, R., 1989. The Rustle of Language. Trans. Richard Howard. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cameron, A., 1995a. Dissimulations: Illusions of Interactivity. Millennium Film Journal, No. 28, Spring [online]. Available at: <http://mfj-online.org/journalPages/MFJ28/ZapSplat.html> [Accessed 10 November 2010].

Cameron, A., 1995b. The Future of an Illusion: Interactive Cinema. Millennium Film Journal, No. 28, Spring [online]. Available at: <http://mfj-online.org/journalPages/MFJ28/ZapSplat.html> [Accessed 10 November 2010].

Casetti, F., 2009. Filmic Experience. Screen, 50(1), Spring, pp. 56-66.

Casetti, F., 2011. Back to the Motherland: The Film Theatre in the Postmedia Age. Screen, 52(1), Spring, pp. 1-12.

Charney, L., 1998. Empty Moments: Cinema, Modernity, and Drift. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Crescendo (Chris Hales, UK, 2003)

Denis, Todd M., 2010. Sufferrosa, Neo-Noir Interactive Film Tackles Cult of Beauty. JawboneTV, 4 May 2010 [online]. Available at: <http://www.jawbone.tv/articles/item/485-sufferrosa-neo-noir-interactive-film-tackles-cult-of-beauty.html> [Accessed 27 September 2011].

The Dreamers (Bernardo Bertolucci, UK/France/Italy, 2003)

The Erl King (Grahame Weinbren and Roberta Friedman, 1983-86)

Hales, C., 2002. New Paradigms<>New Movies: Interactive Film and New Narrative Interfaces. In: A. Rieser and M. Zapp, eds. New Screen Media: Cinema/Art/Narrative. London: BFI Publishing, pp. 105-119.

Hales, C., 2005. Cinematic Interaction: From Kinoautomat to Cause and Effect. Digital Creativity, 16(1), pp. 54-64.

Jinx (Chris Hales, UK, 1996)

Jones, Steven E., 2008. The Meaning of Video Games: Gaming and Textual Strategies. New York: Routledge.

Kreutzer Sonata (Grahame Weinbren, 1991)

Laurel, B., 1993. Computers as Theatre. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing.

Le Grice, M., 1995. Kismet, Protagony, and the Zap Splat Syndrome. Millennium Film Journal, No. 28, Spring [online]. Available at: <http://mfj-online.org/journalPages/MFJ28/ZapSplat.html> [Accessed 10 November 2010].

Lessing, G., 1962. Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry. Trans. Edward Allen McCormick, New York: Bobbs-Merrill.

Lister M. et al., 2003. New Media: A Critical Introduction. London, Routledge.

Lunenfeld, P., 2004. The Myths of Interactive Cinema. In: Narrative Across Media: The Languages of Storytelling. M-L Ryan, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Metz, C., 1975. Histoire/Discours. In: Langue, discours, societé—pour Émile Benveniste. J. Kristeva, J-C Milner and N. Ruwet eds. Paris: Le Seuil.

Morris, E.E. 1982. Morris’s Dictionary of Australian Words. Adelaide: John Currey O’Neil Publishers.

Mulvey, L., 1975. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3), Autumn 1975, pp. 6-18.

Mulvey, L., 2006. Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image. London: Reaktion Books.

Naimark, M., 1998. Interval Trip Report: World’s First Interactive Filmmaker, Prague [online]. Available at: <http://www.naimark.net/writing/trips/praguetrip.html> [Accessed 5 January 2011].

Natural History (Chris Hales, UK, 2003)

Obsession (Pia Tikka, Finland, 2003)

Plantinga, C. and Smith, G.M. eds., 1999. Passionate Views: Film, Cognition, and Emotion. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Plantinga, C., 2009. Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press.

quietearth., 2010. Polish techno-neo-noir choose your own adventure in SUFFERROSA [online]. Available at: <http://www.quietearth.us/articles/2010/03/02/Polish-technoneonoir-choose-your-own-adventure-in-SUFFERROSA> [Accessed 25 January 2011].

Rieser, M., 1997. Interactive Narratives: A Form of Fiction? [online]. Available at: <www.martinrieser.com/Interactive%20Narrative.pdf[Accessed 5 January 2011].

Rheingold, H., 2002. Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution. Cambridge, Mass.: Perseus Pub.

Rokeby, D., 1995. Transforming Mirrors: Subjectivity and Control in Interactive Media. In: S. Penny, ed. Critical Issues in Electronic Media. Albany: State University of New York, pp. 133-158.

Rose, S., 2011. This Week’s New Film Events: Moves 11, Liverpool. The Guardian, 23 April 2011 [online]. Available at http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2011/apr/23/this-weeks-new-film-events[Accessed 27 September 2011].

Schechner, R., 2002. Performance Studies: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

Sontag, S., 1996. The Decay of Cinema. The New York Times, [online] February 25, 1996. [online]. Available at: <www.nytimes.com/books/00/03/12/…/sontag-cinema.html> [Accessed 20 December 2010].

Taleb, N.N., 2003. The Black Swan. London, Polity Press.

Tate, C., 2010. Sufferrosa Movie Joins Interactivity, Music and Art [online]. Available at: <http://www.thespacelab.tv/spaceLAB/2010/06June/MusicNews-05-Sufferrosa.htm> [Accessed 25 January 2011].

Taylor, L. N. 2002. Videogames: Perspective, Point-of-View, and Immersion. Ph.D,.University of Florida. [online]. Available at: <http://etd.fcla.edu/UF/UFE1000166/taylor_l.pdf> [Accessed 5 January 2011].

Tikka, P., 2004. (Interactive) Cinema as a Model of Mind. Digital Creativity, 15(1), pp.14-17.

Tryon, C., 2009. Reinventing Cinema: Movies in the Age of Media Convergence. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Weinbren, G., 1995a. In the Ocean of Streams of Story. Millennium Film Journal, No. 28, Spring [online]. Available at: <http://mfj-online.org/journalPages/MFJ28/ZapSplat.html> [Accessed 10 November 2010].

Weinbren,G., 1995b. Mastery: Computer Games, Intuitive Interfaces, and Interactive Multimedia. Leonardo, 28(5), pp. 403-408.

Willemen, P., 1994. The Fourth Look. In: Looks and Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory. London: BFI Publishing; Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Witmer B. and Singer M., 1998. Measuring Presence in Virtual Environments: A Presence Questionnaire. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 7(3), pp. 225-240.

[1] Note that Espeth also argues that the term operates textually rather than analytically by connoting vague associations of “user freedom, and personalised media while denoting nothing”. Also note Martin Lister et al’s (2003, pp. 21-22) definition: “Interactive signifies the users’ (the individual members of the new media ‘audience’) ability to directly intervene in and change the images and texts that they access. (…) There is a sense in which it is necessary for the user actively to intervene as well as viewing or reading in order to produce meaning”.

[2] These are terms which Aarseth (1997, pp. 1-2) uses in framing what he calls ergodic literature, which is literature where “nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text”, as opposed to non-ergodic literature, “ where the effort to traverse the text is trivial, with no extranoematic responsibilities placed on the reader except (for example) eye movement and the periodic or arbitrary turning of pages”.

[3] There are contradictory assertions as to the number of interjections in Kinoautomat. Chris Hales (2005) writes that there were 9; Naimark (1998) writes 10. It is also important to understand that not all the votes called for were to progress the narrative. As Hales (2005, p. 56) explains, “only five of these choices [in voting] could cause a genuine change in the plot (the other votes were to express opinion, for example whether the audience thought Mr Novak was guilty).”

[4] Martin Rieser (1997, p. 5) elaborates: “In Weinbren’s Sonata, the viewer can only control aspects of the narration—moving from the murderer of Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata telling his story in the railway carriage to the events themselves, which can in turn be overlaid with the mouth of Tolstoy’s wife berating the author, references to Freud’s wolfman case, Judith and Holfernes etc”.

[5] Assuming the tree is non-recombining, i.e. every ending is different, and each decision leads to a different ending. Otherwise, the number of routes would be 2^N, where N is the number of endings.

[6] The only kind of wave with a definite position is concentrated at one point, and such a wave has an indefinite wavelength (and therefore an indefinite momentum). Conversely, the only kind of wave with a definite wavelength is an infinite regular periodic oscillation over all space, which has no definite position.