Uploaded 29 May 1998 | Updated 31 July 1998

Combining words with images for narrative purposes dominates work by some of New Zealand’s most important contemporary painters, just as their use of landscape to comment on New Zealand rather than merely glorify its spectacular beauty also distinguishes the work of modern era New Zealand painters from their predecessors.

In her films, The Red Wheelbarrow (1984) and Divided Attention (1990-93), Bridget Sutherland uses words on surfaces in unexpected ways. This short paper examines Sutherland’s two films within their context of New Zealand art and culture as well as their relation to other arts.

The Red Wheelbarrow was screened in 1984 as part of a New Zealand TV series called Kiwi Shorts. As the announcer introducing the film notes, the images are edited to the rhythm of the music. Sutherland has told me that the soundtrack, which took a year to produce, involved a composer who was aware of both the source poem and the U.S. music context. The announcer also tells us that Sutherland took inspiration from Len Lye, New Zealand’s best-known filmmaker prior to the recent international successes of Kiwi feature films. Another contemporary New Zealander, Leon Narbey, has also, like Lye, worked as a painter, kinetic sculptor, and filmmaker; it seems likely that his work also feeds into Sutherland’s.

However, I shall leave these particular interrelations and influences aside, and focus instead on some aspects of the relation between Sutherland’s The Red Wheelbarrow and William Carlos Williams’ poem, on the one hand, and the context of New Zealand painting, on the other. To refresh our memories, here’s Williams’ poem, written in 1923 [2] .

The Red Wheelbarrow

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

Williams adheres strictly to a pattern of alternating three words with one word; in terms of syllables, the pattern is again strict: 4/2, 3/2, 3/2, 4/2. While Sutherland employs different patterns, she does use regular alternation and groupings in terms of pairs, as we can see if we look at the “text” of her film.

“Text” for The Red Wheelbarrow [3]

4, D3, 2, A1, 0, 5, 0, [FL]AMMABLE [LI]QUID, NOW, DREAM, IT, DREAM, IT, DREAM, IT, DREAM, IT, -, IT, -, E, -, E, -, S, -, S, ES, E, S, E, S, E, A, S, E, S, E, S, E, A, FF, IT, LOADING, IT, LOADING, IT, LOADING, IT, OFF, A1, 5, 4, D3, 2, A1, 0, , 0, , 0, , 0, W, , , , -, , , -, DBK, AE, DBK, AE, DBK, CA, DBK, AE, X, S, X, S, X, S, X, 5, 4, D3, 2, A1, 0, D3, 2, A1, 0, B, A, C1, A, S, X, S, X, S, X, 5, BEST, IRON, R, E, D, R, E, D, R, E, D, AE, , AE, , AE, , BEST, IRON, R, BEST, IRON, R, BEST, IRON, BEST, IRON, R, BEST, IRON, R, BEST, IRON, R, IRON, D, R, IRON, R, IRON, R, IRON, R, U, D, U, D, U, D, U, D, U, D, R, E, D, R, E, D, R, E, D, T, H, E, T, H, E, T, H, E, R, E, RED, D, DC, FDC, D, DC, FDC, D, DC, FDC, DC, FDC, D, FDC, D, DC, D, DC, FDC, D, DC, FDC, D, RED, R, E, D, READ, Real, READ, Real, READ, Real, READ, Real, READ, IT, &, BE, SAFE, and, SELL, it, &, BE, SAFE, A1, THIS, IS, US, A1, THIS, IS, US, A1, THIS, IS, SAFE, THE, READ, 5, NEXT, WHEEL, SE, THIS, IS, IT, BE, US, BE, US, BE, US, BE, US, BE, US, BE, US, THIS, IS, it, and, SAME, and, er, OG, er, OG, GA, er, IN, OG, er, CULT, URE, and, ER, GA, CAR, ER, GA, CAR, GA, GA, CAR, GA, A, GA, A, GA, A, GA, A, GA, A, GA, A, R, Un, IT, for, SCIE, ENCE, and, SCIE, ENCE, and, SCI, IEN, ENC, NCE, and, SCI, IEN, ENC, NCE, and, CAR, S, and, DR, IV, VE, Cars, & SE, LESS, er, HERE, LESS, HERE, TO, HERE, TO, REAL, TO, REAL, TO, OR, TO, OR, TO, OR, TO, REAL, STATE, REAL, STATE, REAL, STATE, Real, SELF, STATE, SELF

Williams situates us in a rural setting through the combination of the Red Wheelbarrow itself and the white chickens. He creates color contrasts through the same combination. In addition, Williams’ Red Wheelbarrow underpins the poem’s “story,” such as it is, since the wheelbarrow provides the poem’s enigma: What exactly depends on it and why does so much depend on it? For whom? Who put it there? What does it reflect–through its presence and through that glazing of rain water? Between these questions and the title, the Red Wheelbarrow takes on a larger-than-life stature.

Sutherland’s wheelbarrow also takes on a charged stature. The film’s title points us to Williams’ poem but also to the image of the wheelbarrow itself, an image that comes relatively late in the film. Williams gives us his wheelbarrow sooner, so that the rest might almost seem to follow from it, whereas Sutherland’s wheelbarrow might be said to bring her material together, making those seemingly disparate images cohere. Part of the reason it can do this is that it is eventually presented as a whole image, a rarity in this film. Also, it situates us concretely on a construction site, something that differentiates the film and the poem significantly.

As the Kiwi Shorts introducer notes, The Red Wheelbarrow was “shot on building sites around Auckland and it looks at the city and especially the language of the city in ways that relate to contemporary painting and sculpture.” Sutherland’s Red Wheelbarrow is not only situated in an urban environment rather than in Williams’ rural environment, but Sutherland’s use of landscape should be seen within the historical context of New Zealand paintings, just as her combination of written text with visual images fits within a contemporary thread of New Zealand painting.

To demonstrate that this is so, I will review a selection of New Zealand paintings, many of which come from the extraordinary collection developed by Victoria University of Wellington.

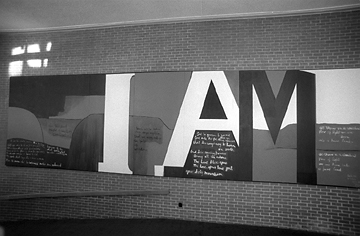

Colin McCahon, who lived from 1919 to 1987, is perhaps New Zealand’s most significant painter. Pretty much from the beginning of his career, he differed from the general practice of other New Zealand painters, in that he did not use New Zealand’s landscape merely for its splendid pictorial beauty. One of his major works is Gate III‘. Note the combination of letter as graphic element, with landscape, and extended passages of (handwritten) textual material.

Numbers, a sketch from 1966 for a University of Otago Library mural, shows some of McCahon’s bent for numbers. An earlier work, Tomorrow Will Be the Same But Not as This Is, from 1958, shows an overwhelming presence of landscape, but literally grounded in the text, and One, from 1965, shows the combination of text and numbers. It also returns us to the concern with the ego evinced by Gate III

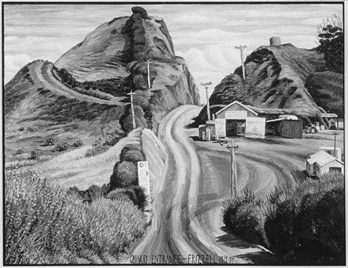

In the mid-’60s, in Tabernacle, a work that typifies his most characteristic visual style, Don Binney also combines landscape and text. And in 1989 Dick Frizzell produced Quarry Entrance, which, like Binney’s Tabernacle, combines text and landscape. It subordinates text to landscape, though – a distinction that separates both Tabernacle and Quarry Entrance from Colin McCahon’s later works.

In New Zealand Federation of Farmers, an undated work by Garth Tapper, who was born in 1927, we see letters again as important compositional elements, but they are literally in the background. The emphasis is on the human figures, with the landscape noticeably absent.

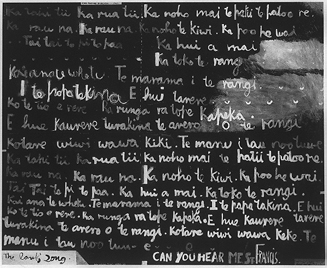

Let me conclude this survey with three pieces by the Maori artist Ralph Hotere, whose work is now perhaps as significant for New Zealand painting as that of McCahon.

In Untitled, a work from 1970, Hotere includes poetry written by fellow New Zealander Bill

Manhire, whose poems Hotere has illustrated for publication. For example, there’s Black Painting XI, also from 1970, and there’s Song Cycle ’75‘. Garth Hall, writing in 1973 about a series of Hotere’s paintings that deals with race relations, notes that “words play an important role recalling the conflict between the Pakeha and Maori. . . . [In this series] Hotere is careful to make the words visually sit upon the surface.” [4] For Hotere, then, text can be less integral to his paintings than it is for McCahon’s work produced in much the same period, e.g. The Lark’s Song (1969, incorporating an eponymous poem by Matire Kereama).

Unlike the gloomy and pessimistic tone of much work by McCahon and Hotere, Sutherland’s The Red Wheelbarrow does not seem somber. However much The Red Wheelbarrow may suggest that we have sold our unreal dreams (as the film seems to be saying via its fragmented images of letters and words that flash in front of us), its social commentary is not apocalyptic – except that the urban landscape in The Red Wheelbarrow is unpeopled.

Furthermore, in The Red Wheelbarrow, text – both whole text and letters used as graphics -is equal to rather than subordinate to landscape. Text has become part of the landscape as a component part rather than as an element of commentary or narrative, as in Tabernacle or Quarry Entrance. It enables The Red Wheelbarrow, in Sutherland’s own words, to comment “on the way that capitalism saturates our environment.” Whereas words and more especially numbers take on a symbolic and often religious function in McCahon’s work, they seem stripped of their density in Sutherland’s film, where their fragmentation and speed of appearance almost deprive them of meaning. They are merely part of the visual landscape of urban Auckland, an Auckland dominated by cars, real estate, and construction sites rather than real states of the self. From this perspective, because of its emphasis on the social rather than the apparently personal, Sutherland’s film differs greatly from Williams’ poem.

The urban landscape remains important in Sutherland’s second film, Divided Attention (1990-93).

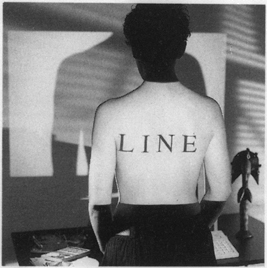

However, commentary on the urban environment occurs now within and through a story about conflicts centered on individual identity occurring between two partners, with an emphasis on the woman’s perceptions. In addition, the woman’s body is juxtaposed against various texts, mostly commercial in nature, so that it functions as part of that commentary, pointing to her commodification as well as her alienation.

Divided Attention belongs among the “theory films,” those films–made by such international women filmmakers as Sally Potter, Laleen Jayamanne, and Yvonne Rainer -that can be read as practical responses to film history and feminist film theory. But this is another topic, which I hope to take up another time.

Sticking with what Divided Attention has in common with The Red Wheelbarrow, we should look further at Sutherland’s interest in how words and images can be joined in narrative. Part of the battle between the couple in Divided Attention is about access to subjectivity: Who gets to utter the words, create the text, and tell the story? The man, Daniel, is writing a novel; Claire apparently works as a secretary and then comes home to enter Daniel’s handwritten work into the computer.

They quarrel over whether or not she comprehends his words. Ultimately, what Claire thinks of Daniel’s text becomes obvious when she writes “mumbo jumbo” over his whiteboard notes.

Eventually, she moves from being the transcriber of his text to being a surface for the projection of a text: the word “line” as well as other images. Later in the film she is trapped between two signs for a public toilet, trapped, that is, between “Women” and “Ladies,” under attack from Daniel’s rage and frustration.

At a point soon after, Claire says that she has always gone out with men brighter than herself, but that this has had its drawbacks, since she “never liked looking up words.” Perhaps the most ambiguous point in Claire’s relation with words comes in the film’s last line. Claire has been telling of her dreams and visions and has referred to a threatening yet vague external force; in her last words, she tells us that she “didn’t dream of naming it.” For those of us steeped in the discourse of women’s studies, “it” evokes both “the problem that has no name,” i.e., sexism, and the fact that simply naming the problem has often been an effective counter-strategy. Thus Claire’s use of the past tense suggests the possibility that she will eventually name “it,” and thus exert greater control over her own life.

However, at this point I have not only moved away from Sutherland’s use of words and letters as graphic elements, but I have emphasized the personal, especially in terms of “female creativity,” in a way that would not meet with Sutherland’s approval. In a written reply to a student response to her film she notes that, “rather than Claire’s character moving toward self-expression . . . , I have always . . . intended her to represent a movement the other way–toward the schizophrenic side of things–i.e., away from the self toward the emptiness of our technological mechanical society.”

From this point of view, then, Divided Attention and The Red Wheelbarrow have at least two things in common: their use of words and letters as graphic elements appearing on unexpected surfaces, and their social commentary on the emptiness of a world in which commodification leads to alienation. If Sutherland, a trained art historian whose recent projects have included curating programs of other people’s films, gets the opportunity to make another film of her own, it will be interesting to see where her fascination with the relation between words, images, and narrative takes her.

Footnotes:

[1] This article was first published in New Zealand Studies 6, no.1 (March 1996): 24-27. The Red Wheelbarrow was screened in 1984 as part of TVNZ’s ‘Kiwi shorts’ series; Divided Attention was screened in the Wellington and Auckland International Film Festivals in 1993, and was part of the City Gallery ‘Alter/Image’ exhibitions (1993/1994) in Wellington and Auckland for Women’s Suffrage Year, The films are obtainable directly from the filmmaker. Permission from the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust and Bridget Sutherland to publish the images accompanying this essay is gratefully acknowledged.

[2] William Carlos Williams, “The Red Wheelbarrow”. In The Norton Anthology of Poetry , eds. Alexander W. Allison et al (New York: W.W.Norton & Co, 1975), 981.

[3] Commas = cuts (from shot to shot); I am unable to represent some symbols, and these letters, words, and numbers appear more randomly in the film than this block presentation would suggest.

[4] Garth Hall, Ralph Hotere (Dunedin: Square and Circle, 1972), 6.