Images virtually rob us of our memory, because they replace it.

– Johan van der Keuken[1]

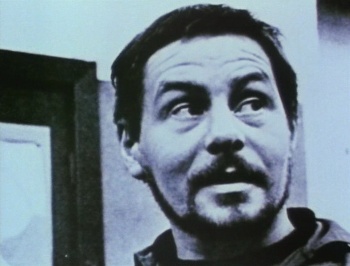

Johan van der Keuken was born in Amsterdam in 1938; he died from prostate cancer in 2001 after a long illness. The son of schoolteachers, he began taking photographs when he was twelve (in the company of his grandfather), and was already publishing his work before he left Amsterdam at the age of eighteen to attend the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC). In the Paris of the 1950s, where figures such as Joris Ivens, Louis van Gasteren, Herman van der Horst, and Bert Haanstra enjoyed critical acclaim, an artistic life must have seemed a daunting prospect for an aspiring young Dutch photographer-filmmaker. As if this shadow didn’t loom large enough, there was also the backdrop of post-war French film culture to contend with – and the emerging genius of the Nouvelle Vague – as well as the achievements of French photojournalism, a cultural project that had already involved Ed van der Elsken, another Dutch photographer-filmmaker and erstwhile surrealist. This was a world rich in talent, and rife with rivalries and anxieties of influence, and while van der Keuken had to work hard to develop a successful visual style, other factors helped him to keep his creative ambitions on track.

His enthusiasm for the (‘anti-Parisian’) CoBrA movement, for example, with its rejection of ‘realistic surrealism’ in favour a more primitive approach to abstract painting, writing, and filmmaking was important. Although its ‘official’ lifespan was short (1948-1952), CoBrA directly influenced a number of Dutch artists who remained close to van der Keuken throughout his career, and who collaborated with him at various times, chiefly: Lucebert (poetry and painting); Willem Breuker (music); Remco Campert and Bert Schierbeek (poetry); and van der Elsken (film and photography). As the above reference to Breuker implies, another vital dimension to van der Keuken’s sensibility was a life-long devotion to Jazz, and ‘free Jazz’ in particular, with its flights of improvised solos, dissonant, anti-melodic juxtapositions, and trips into the unknown. Big Ben/Ben Webster in Europe (1967, b&w, 31 mins.), for example, was one of his own favourite films and throughout his career he, alongside his wife, the sound-editor/engineer, Noshka van der Lely, often created soundtracks featuring both contemporary and classical Jazz compositions. Van der Keuken was also able to avail himself of production funding and distribution opportunities through his association with VPRO Televisie, a liberal Dutch broadcasting company that has supported a number of significant experimental documentary filmmakers since the 1960s. While he clearly disliked many aspects of its modern history and society, Van der Keuken never abandoned the Netherlands – particularly, Amsterdam – and in terms of positioning his work within contemporary Dutch film culture, he soon proved himself adept at producing films that successfully combined political seriousness and cosmopolitan inquisitiveness with a quirky, and natural style, not dissimilar to – rather than derivative of – Haanstra.[2]

Although he studied cinema at the IDHEC, van der Keuken never completely abandoned photography. Its visual and ontological relations to film did much to shape his distinctive approach to framing, editing, and the question of representation. In general, however, the basic formal properties of film – movement, time, and ‘abolishing the standstill’ – countered what he concluded to be the limitations of photography. It was intimacy, indecisiveness, impermanence, and spontaneity that were to become the hallmark of his cinematic style, rather than some of the more fashionable tendencies of the day: objectivity, ‘decisiveness’, stability, and fastidiousness. In fact, van der Keuken’s narrative patterns and deframing techniques, ‘free-form’ camera movement, and abstract colour and sound configurations seem to have less to do with conscious experimentation than a more direct expression of his uncertainties about the possibility of ever framing and representing the world as it is, and was. For instance, he often juxtaposes sequences in such a way as to disrupt the texture of the film with sudden discontinuities, distractions and detours – some improvised, others not. Harsh contrasts of colour and sound, in particular, can unsettle a seemingly realistic representation and disturb the natural flatness of the image, accentuating movement, plasticity, and instability. As François Albera has commented, in his filmmaking, van der Keuken deliberately keeps in play two potentially contradictory impulses: on the one hand ‘there is reality, the world, profuse, multiple, impossible to embrace in its entirety, but which must be seen, ceaselessly filmed and recorded’; and on the other, ‘there is the fact that every image and every sound in this world, captured by the operator’s machines will find themselves, one way or another, projected into another order of reality, that of representation rounded down to one or two dimensions’.[3] The ability to hold this duality in place, to allow different places, situations, histories to co-exist, testifies to a modernist sensibility, and often explains his choice of technique and expressive intentions. In van der Keuken’s films, for example, deframing is essential, registering both a general anxiety about the fragility of perception, and the profound gap or space between the filmmaker and the subject of the shot: the deframed image does not conceal or finesse the unavoidable fact of misrepresentation. As Alain Bergala puts it: deframing in van der Keuken’s work is ‘a relativisation made visible of the act of framing, which reveals the fragility of the arbitrariness of this act and the humility of this decision faced with the sovereignty of the world, rather than a new act of framing which would simply re-affirm, at the same level, the feeling of authority with which the film-maker imposes his will on the visible world’.[4]

Ever sceptical about the positivistic claims of ethnography, van der Keuken’s camera is at its most interesting when it seems a curious, spontaneous and disorientated observer of the essential strangeness of both the foreign and the familiar, new landscapes and cities, experiences, and people. Interestingly, he was particularly fond of a line from Robert Musil’s unfinished masterpiece, The Man Without Qualities: ‘we are motivated both by a strong desire to meet and make contact, and at the same time by an absolute horror of meeting someone else’.[5] While there are various explicitly political and socially orientated films and themes across his work, it is those films and moments when what is being conveyed is a sense of him being somewhere liminal, being ‘in-between’ situations, cultures, styles and interpretations, reticent, uncertain but incorrigibly curious that constitute his most valuable contribution to film art. Not surprisingly, such characteristics often come to the fore in those films where he tries to make sense of loss, the passing of lives and the legacies left behind.

The city

A Moment’s Silence/Even stilte (1963, 10 mins.) offers an early example of van der Keuken’s characteristic approach to configuring co-existing times and places (moments) that relate to one another not only in a suggestive, implicit or reticent way but in a way that can suddenly – scandalously – reveal a lie at the heart of collective memory. Much less ‘photographic’ and lyrical than his first (city) film, Paris at Dawn/Paris á l’Aube (1960, b&w, 10 min.), A Moment’s Silence combines and juxtaposes its Amsterdam sequences to prise open the mythology of Dutch resistance during the war, and the ideology of commemoration. After the Nazi bombardment of Rotterdam on 14 May 1940, the Queen and her family, along with some members of the Dutch government fled to London. A Reich administrator was immediately installed with powers to rule by decree. As in France, Belgium, and elsewhere, the indigenous civil service machine and most of the political élite remained in situ and found adapting to occupation preferable to co-ordinating resistance. By the end of 1940, the Dutch Nazi party (N.S.B.) had over 80,000 members (and over 100,000 by Autumn, 1943). At least 25,000 Dutch civilians freely volunteered to fight in the Heer and Waffen-SS during the occupation period. Jews were soon segregated, and easily identified thanks to the bureaucratic efficiency of the Dutch civil service, and were openly and frequently assaulted in the street by N.S.B. members. Closed Nazi guilds were established, political parties were abolished, and conscientious local censors acted promptly to ban music by Jewish composers, and performances by Jewish musicians. Fritz Hippler’s The Eternal Jew/Der ewige Jude (1940) was screened regularly in every major Dutch town. In May 1942 there were 140,000 Jewish people living in the Netherlands; by the time of the Nazi withdrawal in June 1944, 105,000 had perished in or on their way to the Death Camps. There were of course many Dutch people who resisted and attempted to subvert the genocidal policies of the Nazis (including van der Keuken’s older brother) but collaboration was commonplace until 1944, and the mistreatment of returning Jews after the war has long been a source of embarrassment, if not shame – from time to time.[6]

A Moment’s Silence opens with a (stock) high angle, long shot of Amsterdam coming to a standstill to commemorate the dead of WWII, or more precisely the twentieth anniversary of Holland’s capitulation to, and occupation by, the Nazis in 1940. Van der Keuken’s opening images centre on trams and a train, cars, cyclists, on transport, traffic, movement before cutting to a shot of two crowds gathering on either side of Dam Square. The film then cuts to a shot of schoolchildren being led across a road by a clergyman (or certainly, a teacher/authority figure), and then to other children laughing and carrying flowers, before returning to the square, silent, respectful and at a standstill. There then follows a shot of a young girl carrying a box across a bridge; a military-style lorry is visible in the background, and then a woman is shown playing with her dog. And so the film continues, developing into a kind of random tableau of a day in the life of Amsterdam: men salvaging iron on the canal, children playing amongst the rubble of a building site, and so forth. The soundtrack is comprised of background noise, snatches of music and dialogue, and the film contains a number of jump cuts and shots ‘obscured’ by branches of trees, parts of buildings. In another sequence, the camera dwells on a man lighting a small fire on a riverbank, followed by a shot of heavy rain splashing on water and ‘washing’ the pavement. A funfair is next, and children screaming with excitement, frantically waving their orange flags, at one point chasing after one of the carnival clowns who comes too close to them. The carnival motif is carried into the subsequent shots of a parade with marchers in national costume, uniforms, military bands, police on motorbikes, soldiers, and crowds cheering. Finally, the film returns to its initial ‘moment’s silence’, the war commemoration where that crowd is now shown dispersing, and returning to their everyday lives (or ‘Etc.’ as the end title puts it).

At one level, A Moment’s Silence is a loose chronicle of urban life, another experimental ‘city documentary’, a period piece. At another – more metaphorical – level, it is a more complex cinematic meditation on recent Dutch history and what an officially sanctioned ‘moment of silence’ is in fact attempting to silence. Between the opening and closing shots of the official commemoration, all the images collected and included refer obliquely to the war and occupation, and to a child’s eye view of these experiences; van der Keuken was a two year-old when Nazi Germany assumed control of Holland, and he was nearly six when the war ended. These images, taken from three years of actuality filming, build up to a crescendo of marching uniforms and cheering crowds before cutting to a lone teenage boy throwing baskets in the mist. In this sense, the film is also a companion piece to Velocity 40-70/De snelheid 40-70 (1970), which commemorates the thirtieth anniversary of the occupation by accompanying a filmed interview with an Auschwitz survivor with shots and footage of contemporary Holland, and images gleaned not from newsreel archives and photographs from the period but from what van der Keuken sees around him in 1970: authoritarianism, manipulation, corruption: whatever else the past may be, it is not necessarily another country.

The artist

Lucebert (pseudonym of Lubertias Jacobus Swaanswijk, b. 1924) was an important figure within Dutch avant-garde circles throughout the post-war period, and an exact contemporary of Ed van der Elsken. As a successful poet-artist, he co-founded the ‘Experimentele Groep’ and the ‘De Vijftigers’ (‘the Fifties’) writers’ groups based in the Netherlands, and aligned himself to CoBrA, comprised of artists and writers from Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam (hence, the group’s name). As a poet, Lucebert was influenced by various automatic, oneiric and nonsense techniques derived from Dada, and Surrealism. He was also drawn to rebellious causes and dissident opportunities. In addition to contemporary social issues in the Netherlands, his poetry refers to (post)colonial Indonesia (the Dutch East Indies), the history of slavery, the overthrow and murder of Salvador Allende, and other political figures such as the South African, Breyten Breytenbach, a noted opponent of apartheid, and another poet-painter. In particular, Lucebert shared with other ‘De Vijftigers’ artists, a deepening hostility towards his parents’ generation, as well as a large measure of incredulity at what they had allowed (and, in some cases, had encouraged) to take place before, during, and after the war.[7] His essentially anarchic cast of mind was inevitably drawn to CoBrA, with its own rejection of bourgeois hypocrisy and the tyranny of ‘taste’. CoBrA insisted on a return to the primitive, to the fantastic and folkloric, to the ‘pure’ art of children, and the ‘impure’ scribbling of adults. Inaugurated in 1948, CoBrA was generally left-wing in its sympathies, and within a year, it comprised over fifty members, and encompassed the work of artists such as Karel Appel, Aldo van Eyck, Carl-Henning Pederson, and Asger Jorn (who would subsequently find a second home in the Situationist International). CoBrA championed spontaneity, hedonism, and an unbridled expressionism that sought to shock and scandalise the otherwise austere, gloomy, and guilty demeanour of European culture in the aftermath of the war. Lucebert’s working-class father and grandmother reared him within a strict Calvinist tradition (his parents divorced when he was two), and in 1944 the Occupation government sent him to a Forced Labour Camp in western Germany: the child is the father of the man.

Van der Keuken’s Lucebert: Time and Farewell/Lucebert: Tijd en afscheid is a trilogy comprised of short films from 1962, 1964, and 1994. The 1962 film was produced for the Ministry of Culture as part of a series on contemporary Dutch artists; the other films in this series examined the lives and work of two Dutch cartoonists (Yrrah (Harry Lambertink), and Opland (Rob Wout)), and Shinkichi Tajiri, the Dutch-American sculptor, painter and filmmaker (and CoBrA member). These artists – at least in the 1950s and 1960s – shared Lucebert’s highly sceptical and anti-authoritarian outlook. This part of the trilogy is formally conventional and uses a recording of Lucebert reading some of his poems to accompany the images, complementing and counterpointing the gestural and aesthetic affinities between writing and ink-drawing, a relation that fascinated the CoBrA artists. The 1962 film also includes inserts of numerous still photographs of Lucebert, and more intimate images, such as footage of him with his children at a birthday party, all of which tends to accentuate an important contrast between the playfulness of the man, and the seriousness of the world outside: “We are sleepwalkers in a cold circus”, his voice intones at one point. There is also an unambiguous association made between the grotesque, monstrous images and masks that he draws and paints as an adult and his own childhood (and the war). The second part of the trilogy (which was also funded by the Dutch government) is more sophisticated in terms of its structure, and production values (it is shot in colour). Again, the hardships of Lucebert’s childhood remain a leitmotif and the film opens with a montage of archive images of Amsterdam slums in the 1930s, and press cuttings and other photographs of rioting and police brutality at this time. Van der Keuken establishes a set of juxtapositions: a grainy, b&w portrait photograph of Lucebert as a child, followed by a close-up of his contemporary artwork (dark, dense oil paintings of monstrous faces and distorted bodies, with shark-like teeth and bulbous eyes), and a montage of images from the riots, followed by shots of deserted street-scenes from this part of the city in the mid-1960s. In addition to Beuker’s music, the soundtrack includes animal noises, and other strange wheezing and breathing sounds. Van der Keuken uses rapid montage techniques to ‘exhibit’ the paintings that are gathered together in Lucebert’s studio before cutting to an extended sequence of the artist at work, in front of his canvas, painting a homage to bullfighting. Towards the end of this part of the film, the colour red becomes dominant and leads directly into a montage of raw meat and a row of pigs’ heads lined up at a butcher’s stall, cacti, crabs, and so forth before cutting back to the quotidian amusements of family life. This sequence is followed by graphic shots of a calf getting it throat cut open and being bled to death (in itself reminiscent of scenes from The Way South/De weg naar het zuiden (1980-81). Lines from Lucebert’s ironic anti-racism poem, ‘A Big Gruff Negro’ conclude the film.

The last part of the trilogy is a more personal homage, and as much a meditation on death as a film about Lucebert. The images of his art and writing are still there, but Lucebert’s absence is now the subject of the film, and so too is Van der Keuken’s own sense of loss, and sorrow. The camera pans and surveys the empty apartment and oddly immaculate studio. It seems to nearly caress the scribbles and bric-a-brac of Lucebert’s daily distractions, returning from time to time to a shot of a rocking horse in the room that should of course be stationary but continues to rock nevertheless. At one point, the camera makes a sudden charge at a page of writing on Lucebert’s bed (deathbed?), as if trying to consume its own image, to do something drastic to fill the emptiness, and banish the stillness. The paintings appear again and – like dominoes – fall back and collapse in a neatly edited sequence. The next shot shows children in the studio, playing and laughing. Again, their freedom and innocence is in obvious contrast to the numerous paintings of Lucebert’s dark, cold, surreal ogres. The film closes with another shot of that grainy portrait photograph of the artist as a child: ‘Everything of value is defenceless.’

The loved one

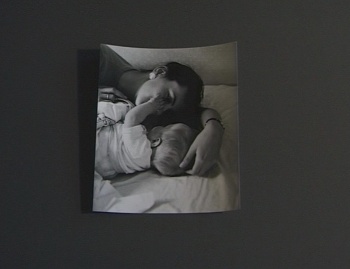

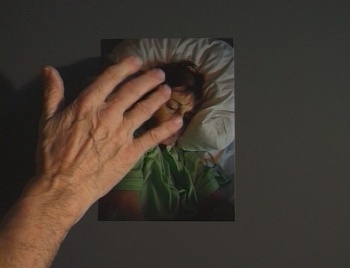

An empty bed, children, and old photographs also feature very noticeably in van der Keuken’s Last Words: My Sister Yoka (1935-1997)/Laatste woorden: Mijn zusje Joke (1935-1997) (1998), a film that documents two conversations between the filmmaker and his terminally ill sister. A therapist at a Jellinek Addiction Clinic for many years, Yoka is candid in talking to her brother about her life and its successes and disappointments: ‘What I know and what I have done is good enough.’ Battling constant discomfort and pain as the cancer destroys her body, she talks hopefully about her daughters, and her grandchild. Many of her reminiscences are generous, and she speaks triumphantly about her rediscovery of painting and music in later life, and the publication of her book on addiction therapies. She also expresses a lingering resentment towards her parents who disapproved of her behaviour at times, and seem to have been incapable of dealing with her unplanned pregnancy when she was nineteen. As the favoured son, van der Keuken is gently reminded that he too is guilty by association. She is happy to be filmed, and – if anything – seems appreciative of an opportunity to record her words and thoughts at this time, to be making a cinematic momento for her brother, and immediate family. As Last Words progresses, her illness worsens and van der Keuken signifies her death by filming a photograph of her lying in her bed, wrapped in blankets and bathed in warm light, eyes closed. It is an image of an image, and his hand adjusts it and he briefly caresses its surface with his fingertips. This sequence also formed part of van der Keuken’s multimedia exhibition, From the Body to the City, which first opened in Paris at Maison Européenne de la Photographie in 1998, and which, he stated, developed from his continued interest in ‘the interaction between photography and film and where the two can viably coincide’.[8] The film then concludes with a montage of snapshots and photographs of Yoka, beginning with images of her in her later years, then as a young woman, teenager, child, and baby in a pram. Some of the images are taken from van der Keuken’s first photography books, We Are 17/Wij zijn 17 (1955), and Behind Glass/Achter Glas (1957), and are the subject of a sharing of histories between the brother and sister earlier in the film. Possibly, this ‘return’ to his photographs also indicates a nostalgia for the solidity and apparent stability of photography in the face of such a profound encounter with the fragility and uncertainty of life.

Other sequences are similarly interesting to consider in terms of van der Keuken’s aesthetic and its availability to experiences of loss and mourning, especially, the film’s opening sequence and the ‘interviews’ with Yoka’s twin daughters, Elsie and Barbara. The film begins with a medium close shot of flowers in Yoka’s garden. The colours and summer sunlight evoke a picturesque scene, an image of life, growth and beauty. As van der Keuken’s hand-held camera then pans right, it stops and allows a window-frame to obstruct the shot. It moves again and repeats this ‘deframing’ gesture, although this time the other side of the image is affected. It then pans through a door and into the sitting room where a conversation then begins. Later, when Yoka mentions her grown-up daughters, the film cuts to a very long take in which the camera simply films each daughter separately. Elsie stands on a balcony above a rehearsing orchestra (her workplace). The shot includes her trying to find the right moment to begin speaking, shuffling a little and composing herself, waiting before she says something about her mother’s illness. Once she has finished the camera slowly pans right and leaves her behind: temps mort. Similarly, in the case of Barbara and her daughter, there is another long take that just never really ‘begins’ in any formal sense and only ends when the little girl shows off one of her paintings (of a zebra). Such sequences are not unusual in van der Keuken’s work (e.g. The Mask/Het masker (1989), Sarajevo Film Festival (1993), and To sang fotostudio (1997), and they do convey the tentativeness and reticence in the face of reality that is a key characteristic of his film style. In this film, these sequences articulate a sense that there is nothing and everything to be said. Despite these gestures, however, Last Words: My Sister Yoka is in many respects quite conventional. If anything, it is Yoka’s film and not van der Keuken’s, as much her final self-portrait as his sympathetic, careful portrayal of his sister’s experience of dying, and his experience of her death.

The self

The Long Holiday/De grote vakantie (2000) is van der Keuken’s last completed film, produced a year before his death, and in some ways a remake of his 1974 film, The Filmmaker’s Holiday/Vakantie van de filmer – although in other ways, not at all.[9] In 1998, van der Keuken was again diagnosed with a cancer; his first illness had occurred in the mid-1980s, and the medical opinion now was that the latest tumor was manageable for the time being but incurable. Together with his wife (and stepson), he headed off on a one-year trip to various countries and places that he and Noska had visited in the past. Travel had been an important aspect of their lives, and filming in far-off (and not so far-off) locations had provided van der Keuken with countless images and stories; often an idea for a film had grown from a certain traveller’s curiosity that then took him to a place where the film would find its own story, determine its own structure and cinematic shape. In Amsterdam (and to a lesser extent, Paris) the world and its stories could sometimes come to him.

In The Long Holiday, and to some degree, Last Words: My Sister Yoka, van der Keuken’s experimental techniques and abstract use of (documentary) film language seems increasingly curtailed by the immediate reality of dying and death. Throughout The Long Holiday, most sequences attempt to record (immortalise) a given location, view, or ceremony and in so doing they also seem to disclose a desire to record the real, to capture a representation that is composed and continuous, stable and reliable. Even the film’s ‘painterly’ closing sequence of boats and barges trafficking in the bay seems to overstay its welcome, and begin to configure itself into a series of pictorial – photographic, even – clichés. At times, the film’s reliance on a conventional realist aesthetic is undermined by something more abstract (for example, the close shots of clinking porcelain tea-cups that seem to symbolise home and companionship as well as time and fragility, some of the intercutting, or the sequence in which he ‘remakes’ Vertigo in San Francisco with a small video camera and a photograph of Noshka, etc.) but by and large van der Keuken’s camera seems now to want to ‘photograph’ the world, framing images and assembling sequences in such a way as to counter the passing of everything, and the loneliness of the self in the strange company of its death. Perhaps, it is true that there are better times to face death than when you are actually dying and that your own death is something you can only encounter as you live your own life. Whatever may be the case, in films such as A Moment’s Silence or Lucebert: Time and Farewell, it does seem that van der Keuken’s avant-garde tendency and formal range could respond to experiences of general mourning and loss in ways that were increasingly impossible when that loss, and the inevitability of dying, emerged in a more immediate, intimate, and solitary form. A line from Lucebert comes to mind: ‘I reel off a small lovely rustling revolution / and I fall and I murmur and I sing.’[10]

Endnotes

[1] S. Toubiana, ‘Le monde au fil de l’eau: Entretien avec Johan van der Keuken: Amsterdam Global Village’, Cahiers du cinéma, no. 517, 1997, p. 55. Translated from French by Lenny Borger as ‘The Flow of the World: Johan van der Keuken’s Amsterdam Global Village’: http://www.moma.org/exhibitions/2001/jvdk/general/general.html.

[2] For some discussion on Van der Keuken’s general engagement with Dutch filmnaking and visual aesthetics, see T. Elsaesser, ‘The Body as Perceptual Surface: The Films of Johan van der Keuken,’ in European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2003, pp.198-211.

[3] F. Albera, ‘A Temporary World,’ Johan van der Keuken: The Complete Collection: Volume 1 (DVD booklet), Arte Video, 2006, p. 7.

[4] A. Bergala, ‘On Photography as the Art of Anxiety’ in Johan van der Keuken, The Lucid Eye: The Photographic Work: 1953-2000, Montreal: Editions de l’Oeil, 2001, p. 21

[5] Toubiana, op cit., p. 49.

[6] For an overview of this period, see: B. Moore, ‘The Netherlands,’ in The Oxford Handbook of Fascism, ed. Richard Bosworth, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 452-468. See also Dienke Hondius’ remarkable study, Return: Holocaust Survivors and Dutch anti-Semitism, Westport (CT): Praeger, 2003. Fons Rademakers’ feature film Like Two Drops of Water/Als twee druppels water was also released in 1963, and also presents a revisionist portrayal of Dutch resistance to the occupation.

[7] Lucebert, Collected Poems: Volume 1: 1949-1952, trans. Diane Butterman, New York: Green Integer, 2010. See also, Lucebert’s The Tired Lovers They Are Machines, trans. Peter Nijmeijer, London: Transgravity Press, 1974.

[8]‘I have been active for a good two decades in the border area between them, and have tried out any number of ways to link two or more photographs outside the ordinary chronological sequence. There are associations and contrasts pertaining to content, story, framework, composition, texture, colour, tone, movement and light. After these series of photographs came the ‘keyhole images’ and the layered multiple exposures (Jaipur/India and Amsterdam/Two streets). What I wanted to do was confront these multiple photographs with moving pictures on film and video and find a different site for film: at some spot where people are walking around anyway, no longer confined to a seat in a movie theater, free to discover the images. A plan for seven exhibitions/installations on seven subjects emerged’. ‘Previous Exhibitions: 1998-1999’, Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris: http://www.mep-fr.org/us/mois1.htm

[9] Van der Keuken was working on For the Time Being/Onvoltooid tegenwoordig (2002) when he died. The film – which is comprised mainly of outtakes and short ‘occasional’ shots and sequences – was edited and released by Noshka van der Keuken as a ten minute montage of friends talking about seemingly random topics, faces looking, and glimpses into other people’s lives.

[10]‘the branded name’/de getekende naam (1952), trans. Diane Butterman, Jacket Magazine, October 2006: http://jacketmagazine.com/31/nl-lucebert.html.

Created on: Wednesday, 17 November 2010