Richard J Thompson interviewed by Anna Dzenis and Raffaele Caputo

Richard Thompson was Head of the Division of Cinema Studies at La Trobe University between 1980 and 1982, and then again between 1985 and 1995. From 1971 until his arrival in Australia in 1980, Thompson taught film at University of California Los Angeles [UCLA] and at the Riverside, San Diego and Santa Cruz campuses. His various film courses included “Film noir”, “The Films of Fritz Lang”, “Introduction to Film”, “History of American and European Cinema: 1945 to the Present”, “Film Genres” and “The Films of Jean-Luc Godard” among many other topics. From 1969 to 1971, he was Research Manager and a faculty member of American Film Institute Center For Advanced Film Studies (Beverly Hills, California) where he conducted critical studies seminars in several areas (his students at that time included Paul Schrader and Tim Hunter), and was also responsible for supervising the Oral History program. Thompson took early retirement from La Trobe University at the end of 2006 and is currently an Honorary Associate in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences.

[To the reader: a caveat or two before you begin. It should be noted that I’m being interviewed due to historical accident – I happened to be at Cinema Studies La Trobe University during a period now under historical study. I have never written a book, although I’ve been fortunate over the years in having some of my shorter work anthologized, mostly work I did before coming to Australia. What follows are the recollections of a decidedly minor player, not a major contributor to either Australian or North American film culture. Finally, I may have forgotten a lot, and so I apologize in advance for omissions and lacunae in my account of events. Richard J Thompson]

……

Tell us about when you entered a writing competition and won a scholarship to the University of Chicago …

RT: I won a writing contest and was invited to several universities I wouldn’t have gotten into otherwise, but I didn’t win a scholarship to Chicago. I was offered a place.

Final-year high school students across the country, state by state, were invited to compete in an essay competition sponsored by the National Council of Teachers of English. I wrote an essay on apathy and I was one of four winners in the state of Oregon; the big universities rushed to offer places to all of the winners. Before that, I just expected to go to the state university, but that all changed. Of all the universities that offered me a place, I chose Chicago because it had jazz and blues and none of the other cities did.

Was your essay on apathy about “apathy and film” or “apathy in literature”?

RT: No, it had nothing to do with film. It was just about social apathy, about not taking a position and not exercising citizenship.

So you went to Chicago because you were interested in the music culture there, but what did you study at the university?

RT: I did literature; it had a good English department. Chicago was a progressive university. Like most universities in the US, it has a four-year undergraduate program, but back in the 1920s and ’30s Chicago started a program where you spent your first two years in something that was called the College, and you didn’t choose a major. You had to take sciences courses, social science courses, mathematics courses, English courses, foreign language and so on. You didn’t have any real choice, but at the end of the two years you then selected a major and specialized in something. That’s what happened.

How or when does your interest in film come in?

RT: I was at Chicago from 1962 to 1966 and so of course there were no film subjects on offer. It wasn’t really until the end of the 1960s and certainly the early 1970s that film courses exploded in American universities. But there was this well-established film society at Chicago, which claimed to be the oldest in the United States. Before classes started in the first year I went to a kind of activities night in a big room and each of the student clubs had a desk and you got to see what was on offer and people pitched things at you. Bill Routt was sitting there at the Documentary Film Group [aka Doc Films] desk and showing Bruce Conner’s Cosmic Ray [1961], which is based on Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say,” and he was showing that as a draw card.

How does jazz and blues intersect with your interest in film?

RT: The music of choice in my family, usually on 45 rpm albums, were Broadway show collections like Guys and Dolls, Kiss Me, Kate, Oklahoma!, stuff like that, but my parents also had five jazz records, a Louis Armstrong, a Fats Waller, a Nat King Cole, a Jelly Roll Morton, and the Benny Goodmam Carnegie Hall Concert. I certainly knew those, but sometime fairly early in high school I started listening to public radio and at 4 o’clock in the afternoon on weekdays when I’d be home from school they’d have a series hosted by Martin Williams, who was an English Professor, but who was also in charge of the Smithsonian Institute’s Jazz Program. It was an education in jazz and I just never looked back. The first LP I bought was on RCA Victor, Duke Ellington At His Very Best, a collection of work from 1939 to 1941, and so before I got serious about movies I was absolutely serious about jazz and have never stopped.

And you’ve fed that interest into movies?

RT: I don’t know if I consciously did it. I had an interest in the range of jazz from the beginning right up to the present and [the approach] carried over to working with film. To be more and more attentive to early film and not to be stuck in the present, but to navigate across the range of film across time since 1895.

In addition to this kind of complete-ism, my jazz experience drew me into research habits like reading everything I could find on the subject, cataloguing, categorizing, and a deep concern with form and style. A fairly recent example of that was when [Anna Dzenis and I] were asked to design a film history half unit. The brief from our colleagues was that this half unit was to guarantee that all participating second and third year students would have seen Battleship Potemkin [1925], Citizen Kane [1941], Rome, Open City [1945], Breathless [1960], the whole classical canon as it stood. We satisfied that requirement, but we also began to devise a second stream, a section of short films or excerpts from other films, so while people could see Potemkin they would also see five or six excerpts or shorts of what was going on at the same time as Potemkin in areas such as documentary, animation, the avant-garde, popular film genres, other sorts of film that broadened the historical and conceptual context. Our concern was that they didn’t go away thinking that from 1922 to 1924 Potemkin stood for all of film history in that time. We wanted them to know what else was going on.

Did you have any interest in film before going to Chicago?

RT: I had a very unspecific interest in film. We didn’t get a television set until I was 10 years old and the only films I saw in cinemas before that were when my grandmother took us twice a year to the latest Disney film, because they released a film twice a year back then. Aside from that I saw very few films, although when I was on summer vacation at the beach with my other grandmother, I would get to see a film or two. I can remember seeing Apache [1954] with Burt Lancaster at the Long Beach, Washington theatre. I didn’t know who Robert Aldrich was and wouldn’t for years, but I sure remembered Burt Lancaster being kinetic in Apache.

When we got a TV, it all changed because the studios were clearing out their backlogs and putting together huge packages of films and renting them to the television networks and stations. I was able to see a great variety of post-sound Hollywood in a very disorganized way. I developed my own auteur system – I’d see anything with Errol Flynn or John Wayne or Humphrey Bogart in it. That actually was useful later because they had worked with interesting directors, or directors I was interested in later. Anyway, Bill got me into the film society and I suppose that was the beginning of my systematic or conscious attempt to learn about and think about film.

Was Bill Routt a student there at the time and running the film society?

RT: He was. He was an MA student in Anthropology and that’s why Bill speaks Urdu as well as French.

The Documentary Film Group represents a certain kind of film society but because you mention the Bruce Conner film, does that mean there were there two kinds of components to the Group?

RT: It developed a tradition of paying particular attention to experimental and avant-garde American film. It was also seen as the outpost for such filmmakers between New York and San Francisco, which were the two hot spots of American experimental film at that time. They’d break their journey in Chicago and we’d have a film night – screen their films, talk with them.

But you are right the other part of it was a weekly film series on Friday nights. Then after I began running it we had films on Friday nights and Tuesday nights with some series theme or topic. My one entrepreneurial success in life was when I succeeded Bill as Chairman of the Documentary Film Group, which was subsidized and always in debt to the university. I actually pulled it out of debt and kept it out of debt when I was programming it.

How did you manage that?

RT: I put on a series called The Bogie Flicks, which was ten weeks of Humphrey Bogart films. That got us out of debt.

So why was it a ‘documentary’ film society?

RT: Because when it started back in the 1930s, documentary is what they were showing. It was very leftwing and they were showing documentaries about social issues, the depression and about unions and so on.

What else did you show? How were your interests forming? Did you program movies that you wanted to see?

RT: Everything, and I wanted to see almost everything. I was very unselective, and showing a lot of European film. You also have to keep in mind that this was in the early ’60s. It was when the Spring 1963 issue of Film Culture came out, the issue totally devoted to Andrew Sarris’ American directors canon and the Documentary Film Group subscribed to Film Culture. That explosion of auteurism sponsored by the journal was a strong influence on many of us, and so we began to program in line with the kinds of things Sarris was pointing to. Not everyone; some members couldn’t see the importance of screening, say, Howard Hawks.

Was it a film society for university students?

RT: It was in a university community but also within an enclave of ten blocks by ten blocks around the university and part of Hyde Park on Chicago’s South Side. It was a very active and intellectual community. It’s where Barack Obama later did his community work, much later. People who came to the screenings were not just students; they were people from around the community, and a very intellectual community. That was how Bill Routt and I got published in december, because Robert Wilson, the film editor of december, lived in the neighborhood and came to the screenings.

Sounds like it was a very active film society.

RT: Film society culture in the United States was very well developed and very active, at least in the ’60s. We’d go to other film societies around the Chicago area and they’d come to ours. There’d be an annual weekend of screenings where the 16mm distributors would loan prints of the new films they were trying to promote and you would spend a weekend from 9:00 in the morning until about 11:00 at night watching film after film after film.

It’s interesting that there were a number of film societies or groups networked at that point in time.

RT: Yes, and they were generally based at universities and art museums. When I left university I went to work in that area, 16mm film non-theatrical distribution. It was the film society experience that directed where I wanted to develop work and it was also where I started reading seriously about film – what literature there was in the ’60s.

Apart from Film Culture, what was around in the United States?

RT: Film Quarterly and Sight and Sound, Film Society Review, and after I got serious I certainly subscribed to Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, also Études cinématographique and Prémier plan, then Screen and Movie and everything else as more journals appeared.

You were reading in French?

RT: Yes, I took French in high school, and we had to pass a language exam in first year university, or we would have to take a language course until we could show reading proficiency in that language.

How were you hearing about what was going on with the Cinématheque and the New Wave in France? What was your sense of French film culture when you were at Chicago?

RT: Bill’s journal Voyeur, published by Doc Films, collected such information from all over – maybe 15 per cent of the journal was news, along with a continuing “Glossary of French Cinematic Terms” and translations from the French, largely Cahiers. Sight and Sound and Film Quarterly and, coming along, Film Comment were devoting attention to events in France, and if you were getting Cahiers and Positif you were certainly getting a lot of information about what was going on in France.

And you actively pursued films by Jean-Luc Godard, for example?

RT: One of the first articles I published was a very adolescent, enthusiastic article on Godard.[1] I think it was my third or forth published article in december, the magazine that never capitalised its ‘d’.

Tell us a little bit about december and how you got published there?

RT: december was what was called a ‘little’ magazine, a literary magazine, not very commercial at all. It originated to publish poetry and short stories. Bob Wilson, the guy who became the film editor at december, kind of befriended the publisher and talked him into opening up a film section and that’s how the film section happened. Maybe it was in the issue that I published “Meep-Meep!”, I can’t remember but anyway there I am in the film section and there is Joyce Carol Oates in the short story section – both of us unknowns at the time.

“Meep-Meep!” was published quite early in december and it’s an article that has been anthologized several times.[2] How did that particular article come about?

RT: I had seen American animation studio cartoons on TV from the time I was ten until the time I went to university. But I wasn’t thinking about them; I was just taking them in or absorbing them. Then when I was working for one of those 16mm film distributors I was looking at some of the things we were distributing and discovered we were distributing some Road Runner cartoons as part of a package. I was quite interested in them and started thinking about them and started talking about them to Bill Routt. Bill said, “Why don’t you write about them?” So I did, and Bill and I had already made a connection with december while we were at university. It was an annual journal and as the time rolled around Bob would get in touch with us and say, “You got anything for me?” That year I had “Meep-Meep!” for him.

It was very radical in making claims for animation artists as auteurs. In fact, Chuck Jones mentioned that article as particularly important for his broader critical acknowledgement.

RT: But if you go back to 1943, Manny Farber published a piece on Warner Brothers cartoons singling out Chuck Jones.[3]

Now that you’ve brought up Manny Farber, wasn’t it around this same time that you were teaching film with Farber or had taken over teaching film from Farber?

RT: 1971 was the first time.

When had you known of Farber?

RT: At the University of Chicago, which was a very intellectual ‘talkie-type’ university, there was an English subject where we were taught to write critical essays. One semester we had to read an essay called “The Westerner” by Robert Warshow,[4] and we had to write about it and talk about it in class. Everybody in the class condescended to it, spat on it, denigrated it for daring to discuss western movies seriously, but I wrote an essay that was very positive about it. I thought it was a terrific and useful and good article and fortunately the lecturer also thought so, and I was encouraged to read further. We had a very small library in the Documentary Film Group and there wasn’t much serious literature about film at that time, but there was a book edited by Dan Talbot, who operated The New Yorker theatre, a very important revival house for New York film culture. The book was Film: An Anthology.[5] I started rooting around in that because it had “The Westerner” in it, and right after that essay there was an essay called “Underground Film” by Manny Farber[6] – I was really taken by it. Then I went to the university’s library whenever I could – they had a terrific library – and they had bound volumes of things like The New Republic and The Nation going back to the 1930s, so I read everything I could find by Manny Farber in those periodicals.

What first struck you about Farber’s writing?

RT: Style, and the kind of connections he made with films to other things in culture. The ideas that he used that other people didn’t use. He wasn’t within the box, the box that was given to us from the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, the great canon of films, about what you could take seriously and what you wouldn’t even bother talking about. Farber wasn’t doing that; he was doing other things entirely – showing you a new way of seeing, receiving, perceiving.

That’s interesting because the popular myth about the Cahiers du cinéma critics is that they discovered American cinema beyond the canon, or that here were these B graders who were just as important as the canon. But Farber was obviously doing that earlier and by the time one gets to the French New Wave, Farber was already somewhere else?

RT: Oh yes, when everybody else was writing about the auteur directors, Farber went somewhere else. He always did that. I describe him as some kind of Daniel Boone figure because in American history and mythology Daniel Boone always moves further west as soon as he could see the smoke from his neighbour’s cabin.

And what about Warshow?

RT: Warshow was a product of a slightly different cultural push, which I think began in the ’20s with Gilbert Seldes,[7] which was to look at what was called mass art or mass culture and which became pop culture. Warshow was looking more generically at types of films, as he does in “The Gangster as Tragic Hero”,[8] and “The Westerner” and so on.

And to make a connection between Farber and Warshow, when I was doing film distribution in the ’60s, I was sent to Head Office in New York and my counterpart there, who was doing the same job as I was, which was writing catalogues and promos, and who was put in charge of taking care of me, was a guy called Paul Warshow. He was Robert Warshow’s son and he said to me, “You got a week here, is there anything you’d like to do while in New York?”, and I said, “Yeah, I’d like to meet Manny Farber.” He said, “I’ll call my friend Pauline, I’ll bet she can arrange that.” So he calls up Pauline Kael, who I had met before because she was a judge at one of our film festivals at Doc Film, and when Paul rang it turned out that Manny had just left her house about a half hour before. She rang him up and we went over that night and I met Manny Farber. I talked to him and out of that came the profile that ran in december.[9] I didn’t have a recorder and I didn’t know anything about interviewing, but by then even I knew interviews were a big genre of film journalism.

It’s interesting that you go New York and the one thing you want to do is to meet Manny Farber. There’s a thread running through your work of very consciously seeking out critical writers and responding to them and writing about them. Were other people doing that?

RT: I think that was probably a general trend running through film societies at the time.

Back when we look back on that period, I don’t think there were many people writing about film critics. Were you thinking about seeking a path to writing about film?

RT: I don’t know. If I did, it wasn’t conscious. I didn’t have an agenda, a plan for the future.

Well, were you seeing Farber in the same light as, say, Sam Fuller? You may not have had a plan but did you see them as individuals who were similarly creative in their respective fields?

RT: Absolutely, but I didn’t do as much seeking out as you might think, and some of that happened through the film society in the 1960s. For example Bill Routt started Voyeur and it was exactly what you might think, a little magazine but quite active, and I published a couple of things in that. We managed to interview or meet people who were either sponsored by the film society or who were just passing through and we’d say, “Came out for a day,” or we’d go down and see them somewhere. We had John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and I can remember we went down town and talked with Otto Preminger for a little bit after a preview of Hurry Sundown [1966], and a few of us talked with Jerry Lewis between acts in his dressing room at a nightclub.

But when I got to the American Film Institute [AFI] in Los Angeles, I didn’t have to try to seek anyone because there was a stream of people coming through there, giving seminars and talks, doing this and doing that. We didn’t have to seek out anyone; they came to us.

But you must have selected the people you wanted to talk to when you were doing the oral histories?

RT: Oh no, the people I’m talking about weren’t the oral history subjects. The guys – and it was almost totally males at the time – interviewed in the oral history program were usually people whose careers were over, people whose stories we wanted to record before they were gone.

But the situation at the AFI cheapened the currency because almost every week I’d meet two or three people, like Raoul Walsh or Donald Seigel or John Cassavetes; they would come in and we’d shake hands and exchange a pleasantry. The number of people I met, shook hands and had a pleasantry with became fairly unimportant because there was no real talk or discussion. Some times, fortunately, there was a chance to have 15 minutes or half an hour with someone, one-on-one or maybe two or three on one, just from, say, standing in the courtyard talking, to Budd Boetticher or driving Fritz Lang home, that kind of thing.

So the AFI was established in that period and were you one of its first employees?

RT: My first international publication, which was in the Autumn 1971 issue of Screen, is an institutional study and history of the AFI – a long, detailed piece of research, 40 pages of fine print. The AFI was founded in 1966, and it was based in Washington, DC because this was a Federal Government thing. George Stevens, Jr., who was the first head of the AFI and also the son of director George Stevens, had a career making films for the motion picture division of the United States Information Agency, which basically made propaganda films about the US and distributed them through embassies. Anyway, George Stevens, Jr. had big connections with the Kennedy Administration and got this thing off the ground in 1966. Then in 1969 they started a filmmaker training conservatory in Hollywood called the AFI Centre for Advanced Film Study, which was based in an old mansion in Beverly Hills that they rented for $1 a year from the City of Beverly Hills. Incidentally, I met Harold Lloyd there because the almost identical mansion next door was where he lived.

Anyway, from a national screening program they would select twenty students, or Fellows, each year to study filmmaking and become filmmakers. To dress it up and give it a little academic class, they opened a small area there called the Research Department. One of the activities of the Research Department was an oral history program that had been taken over from the University of California Los Angeles [UCLA]. I didn’t do any of those interviews; I commissioned them, I supervised them and I edited them.

How did you get the job at the AFI?

RT: It was 1969 and I was in my third year of working for non-theatrical film distributors, writing whenever I could. Then I get this phone call out of the blue from a guy I’d never heard of before named Jim Kitses, who asked me if I wanted to come out and be his number two person at the AFI’s Research Department.

Something like, “Go West, young man … ”

Yeah, but it was basically back to where I came from, the West Coast. I was ready to try something like that, and it was for a little more money than I was getting in 16mm distribution.

You were head hunted?

RT: I was and I asked Jim about that; he said that when he was in New York and because he needed a number two person for the Research Department, he asked Andrew Sarris if he could suggest someone who knew American film, knew the literature, knew the issues and debates, and who could write. Well, I never met Sarris but apparently he had read my stuff because he gave Kitses my name. That’s how I got there.

How much had you published by that stage and where had you published for someone like Sarris to know your work? Because Film Comment wasn’t around then, nor was American Film, nor Paul Schrader’s magazine Cinema, and between 1966 and 1969, apart from Bill Routt’s Voyeur, you were only published in december.

RT: Yeah, it’s odd. American Film hadn’t started, Film Comment was around but I think the first three or four issues were under a different title and, anyway, I wasn’t published in Film Comment until much later. By this time I had published in Film Society Review, The Movies, and been anthologized in the Joe McBride edited Persistence of Vision. december was a ‘little’ magazine and I think the print run must have been about one thousand copies. I can only conjecture that Sarris was one in that thousand. How else? I wasn’t a public figure in any other sense, or perhaps Sarris had spoken to someone else who may have said something nice about me. I don’t know.

The AFI is a complex organisation and you seem to have had multiple roles in terms of teaching as well as managing research. Can you describe that a little bit?

RT: The AFI’s little academic component, the Research Department, did oral histories and also supplied a series of weekly seminars and teaching sessions on film history, ideas, theory. Every year, in addition to taking in twenty potential future filmmakers – and examples in my time there include Terry Malick and David Lynch – they would take in two or three research Fellows to be attached to our unit, who would be there to study film history and criticism and film culture and were not exactly in filmmaker training. The irony was that in the first year the two research fellows they took in were Tim Hunter and Paul Schrader, who turned out to be pretty active filmmakers.

Was it being at the AFI that piqued their interest in filmmaking, or did they come to filmmaking from a more critical approach?

RT: Tim’s father had been a blacklisted Hollywood screenwriter. Everybody, I think, knows that Paul Schrader came from a very strict Dutch Reform Church family in Michigan and wasn’t allowed to listen to the radio or dance or do much of anything else. His great liberation was to embrace films and to become a writer and then a director. He was certainly breaking ties with his culture, family and his community by going west and becoming a critic. The first real job he got was with the L. A. Free Press as their regular film critic.

You stayed with the AFI for a while and then you moved into various teaching roles.

Why did you leave the AFI?

RT: After 18 months the AFI left me! One Friday night at 5:30, I was called into the manager’s office at the AFI and I sat in the lobby waiting for his last appointment to end. The door opened and out came the secretary of the Research Department, a person I worked with every day, Jeryll Taylor, and I said, “What are you doing here?” and she said, “I’ve been fired.” Then I went in for my appointment and this very smooth talking guy in a custom-made suit started telling me about the situation of the Institute and its future directions, budget and funding angles, and going on and on about all of these things. I’m just sitting there because I’ve always been very institutionally naïve; I’ve never learned how to work in institutions. After 10 or 15 minutes of this I begin to get the picture and I say, “Wait a minute, you’re firing me?” After some more waffle and spin, I ascertained that yes he was firing me and so I walk out of the door and sitting in the anteroom was Jim Kitses, my boss at the Research Department. Jim looked at me and I looked at him and I said, “Meet the unemployed!” Jim went in and got fired too. That was how I left AFI.

What was the background?

RT: Budget cuts and different priorities. They didn’t think the Research Department was as important as something like their archival work. I would have to agree. It was much more important to be doing film restoration and preservation, all of that sort of stuff. Then I took any job I could get and for the rest of that decade I was working on one-year teaching contracts at the lowest level of academic teaching.

At UCLA?

RT: At UCLA and University of California Riverside and University of California at San Diego.

I thought that a lot of the substantial interviews you had done came out of the oral history project?

RT: They did in an indirect way. As I supervised the oral history program I began to have more and more doubts and criticisms and concerns about what you could and could not do in oral history programs, what you could accomplish, what you could do wrong and what you could do right. It wasn’t until I hit a gap in those one-year teaching contracts or when I was, ahem, ‘between engagements’ that I started doing interviews to make some money.

I’d done the Phil Karlson interview back in the early days but I hadn’t thought much about really interviewing people. Then in my second year at the AFI one of our new research students was Greg Ford and Greg was at least as involved in animation as I was, and we got on extremely well. Coincidentally, that year was also the year Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson left New York and came to the University of California San Diego. They stopped at the AFI to say hello to Greg and Manny and I reacquainted ourselves. We were able to open up that channel again because San Diego is only about an hour away on the freeway from LA.

Anyway, Greg and I hatched this idea that we might interview Chuck Jones. I can’t remember exactly, but it was probably Greg’s idea because he had good New York connections. Greg came from New York and he knew that Film Comment was planning a special issue on animation, and so we did the interview with Chuck and got it in and that opened up an opportunity for me to do more interviews for Film Comment. By then interviews had become – and had been for a decade at least – a very real currency in film journals. Interviews were kind of like you were actually reading or hearing words that came from the mouth of God – sorry, the director.

To backpedal a bit, Greg Ford had the Chuck Jones connection as well as a connection with Film Comment?

RT: I don’t know if he had a connection with Chuck; I think we just cold-called him.

It’s fascinating that you had cold-called him. Had he read “Meep-Meep!”?

RT: I don’t know. He certainly had later because in addition to running the interview, Film Comment also ran one of my Chuck Jones pieces in the same issue, and I think it was “Meep-Meep!” and so Chuck would have read it then after we had done the interview.[10]

And it was the period when you did these quite substantial interviews …

In the space of about a year. As I needed money, I could call up Film Comment and pitch them ideas.

When is your first interview with Sam Fuller and how did you get to know him?

RT: The first one was actually published in Movietone News and it’s the one with the sweet title, “Mom, Where’s My Suicide Note Collection?”[11] Fuller made himself very available to the generation of young filmmakers who were just coming up in the 1960s. He wasn’t doing much active filmmaking at that time, just the odd film, but he was sitting in his converted garage, his study up there just off Mulholland Drive, and was writing four or five complete screenplays a year. One whole wall of his study from floor to ceiling was screenplays, unproduced but completed screenplays, ready to go.

I would have met him at some kind of event where he would have come out to talk to a group of young filmmakers or students. But it wasn’t any problem to just ring him up and say I wanted to do an interview with him for Film Comment and he’d say [affecting Fuller’s voice], “Great, young fella, great, just great. What day ya wanna do it?” I can’t remember why I broke the interview up into two parts and sent some of it to Movietone News and some of it to Film Comment.[12]

I thought you interviewed Fuller on two separate occasions because the one in Movietone News was published two or three years before he had started production on The Big Red One [1980], while the one in Film Comment talks about The Big Red One and includes script extracts of scenes cut from the film.

RT: That might be right, I can’t remember.

My arrangement always with these interviews was that I would take the final edited version to the subject before I sent it to the magazine so they could have a chance to make a change or two. The Fuller interview was no exception; I went up to his house one lunchtime and handed it to him and he said, “Ah, thanks young fella, thanks. Listen, can you leave this with me overnight and come back about this time tomorrow?” Which I did, of course. I went back the next day at about the same time and he said, “Very good, young fella, very good. Here it is.” He hands me the interview and it’s not my interview! It was an interview he had rewritten overnight and where he had put words in my mouth and he gets to say what he wants to say. He wrote my lines too, including stuff I never ever would have thought of asking him, one of which was, “RT: Mr Fuller, have you ever killed a man? SF: Have you?”

Anyway, I had a quandary. I had two complete interviews and I wasn’t going to guess which one was better; I was sure his was better. Finally I got a hold of the magazine and told them what happened, and said, “My best solution is to run the interviews double-column, side-by-side,” which is what they did.

Where is the Farber interview[13] in the context of your other interviews for Film Comment? Were you teaching for him at this point?

RT: Once he moved to San Diego we saw each other quite a bit. The Manny interview comes at the end of the series of interviews. It was late in ’76, and Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson were doing their last writing about film. I asked him why he stopped and he said, “Because writing film criticism is just too hard.” In many ways that comment paralleled my experience of the Manny Farber interview – it was the interview that broke my back as an interviewer and I said, “No more of this!”

As usual, I edited my questions and comments down to an absolute minimum: readers wanted to hear Farber and Patterson, not me. It took about six months; it stopped being an interview in any way. It had been rewritten and reworked so many times that I don’t even know if there is a single line of original dialogue in the published version. I did what I said I usually do, I gave a copy of my first version to Manny and Patricia, and they said, “Listen, can we come up and talk about this?” So they came up on a weekend and we talked about it and made notes and changed things and so on. This kind of back and forth rewriting went on for about six months right up to the deadline. It had really stopped being an interview and became a dialogue. Each of us did so much revising and rewriting and changing. It was kind of wonderful to do, but I just didn’t do any more interviews after that.

It’s a very detailed discussion of Farber’s practice, how he thought about criticism. Did he take this as an opportunity to actually make those statements about his practice, to be a kind of last hurrah?

RT: They certainly took the opportunity to do that, but he and she talked about those ideas and issues all of the time. They were very conscious of those things.

In classes?

RT: Yes. He did a lot of teaching and people don’t mention that. He was very inventive and very creative in his teaching – stopping and starting the film, showing the film without sound, showing the film without images, showing the film over and over.

The way you have described his writing recalls the piece he did on Raoul Walsh[14] which was originally 80,000 words and he had to cut that down.

RT: Sight and Sound gave him a 7,000 word deadline to write about Raoul Walsh and he did, but his rough draft was 80,000 typed words. I was down at San Diego on a weekend when he was paring it down to 7,000 words; he just put everything he could think of or had ever thought about Raoul Walsh on paper.

Did he try to give it to [ Sight and Sound] as 80,000 words? They could have accepted it as a book.

RT: Exactly, but he didn’t.

What was going on there at that point for Farber to say film criticism was just too hard? Was it because he didn’t feel he was appreciated any more?

RT: It may have been that. He was about 60 and because he put so much energy into this kind of thing – as the 80,000 to 7,000 will tell you – maybe it just got to be more than he wanted to do or felt he was able to do. Maybe because of changes in the film culture he saw himself participating in made it less interesting for him to write anymore. He’d already gone through the post-New Wave European filmmakers and it may have been that he couldn’t see anything on the horizon, in that everybody else was now writing about that post-New Wave generation of European filmmakers, particularly the German filmmakers.

Like Straub-Huillet and Fassbinder?

RT: And Godard, Michael Snow, Herzog, Akerman, Ozu. He jumped into that area early on and perhaps he couldn’t see anything after that that attracted him. This is speculation here; he didn’t tell me this.

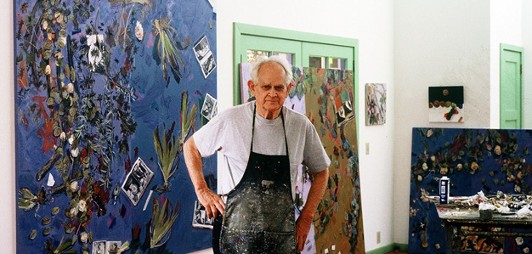

That’s when he tended to do a lot of painting?

RT: Oh yes, he certainly always gave a lot of time and energy to painting.

And maybe one would suggest his painting became visually critical?

Some of them – he would have said all of them. You’re meaning the auteur series and they are great and very playful, kind of like puzzles. He wanted to challenge you with the title and the details of the painting, to see if you can figure out if it’s about Howard Hawks, if it’s Preston Sturges, or if it’s Sam Peckinpah. The Hawks painting is called “A Dandy’s Gesture”; his Boetticher homage is called “My Budd”.

Did you attend any of his classes? What was he teaching when you met him?

RT: I attended a couple. I think he was teaching Anthony Mann’s The Far Country [1954].

That went into the interview; that detailed analysis of the porch scene from The Far Country went into the interview!

RT: The porch scene that everybody forgets. It’s like Raymond Bellour’s analysis of the penultimate scene in The Big Sleep [1946][15] the scene in the car with Bogart and Bacall and Bogart is explaining everything to her. It’s a nothing scene but Bellour gets real gold out of it. Farber got real gold too out of the porch scene.

You’ve shown me some of Manny’s exams, which are very much about detail and analysis. Were those exams published?

RT: I think I published one of his exams with the interview in Film Comment. I was extremely gratified and honoured when the interview was included in the last edition of Negative Space,[16] but I wish they had published the quiz as well. I didn’t write it, but it would have been a very interesting and accurate look at how Manny thought, what Manny thought and what he wanted the students to pay attention to.

I’ve no real sense of his teaching but one would assume he would have talked about a scene for three hours?

RT: He would stop and start, or repeat bits of the film. He thought he was teaching people how to see the film, and I certainly learnt a lot about how to see a film from reading Farber’s writing and from his teaching.

Was he teaching filmmakers or art students?

RT: It was in an art department. He was teaching courses in painting and courses in film, so he was investigating cinematic images in terms of composition and so on. He did that for a lot of years.

So when you went to teach his class, did you teach art students too?

RT: It was the same cohort.

I read somewhere that you also taught Jean-Pierre Gorin’s classes. How did that come about?

RT: Farber had recruited Jean-Pierre Gorin to come teach with him in the San Diego program and Gorin had been doing that for about a year. A couple of weeks before a semester started I got a call from Manny and he says, “Do you wanna come down here and teach?” I say, “What’s up?” And Farber says, “Well, JP was gonna teach this course on the films of Godard but he just got a phone call from Francis Ford Coppola [who is] in the Philippines and Coppola says, ‘JP, get over here right now!’ So JP is not going to teach the course on Godard and I need somebody to do it.” That’s how I ended up filling Gorin’s shoes, uncomfortably, I might add. Gorin is the right person to be teaching a course on Godard.

And did the course work out well for you?

RT: I think so. I remember showing Two Tars [1928] before Weekend [1967] on the same night and talking about the relationships between the two films, especially because of the road scenes, the way cars and roads are used for ironic, comic purposes and the way they both exaggerate time. That’s all I can remember about it.

What was happening in the States at that time in terms of film criticism and theory? Did you like what was happening? And where were your interests?

RT: Earlier I pointed out the 1963 issue of Film Culture and Sarris’s intervention with the clarion call that auteur theory was becoming a wave. The ’60s was filled by that wave and it was on the back of that push for auteurism that a lot of film departments got started at universities. But if you were reading Cahiers and other stuff in the 1960s you sort of knew that they had moved beyond auteurism, that there were theoretical issues, and political issues, particularly after May 1968, that got into the Anglophone film culture in 1970, or whenever it was that Sam Rohdie took over Screen. He made Screen the crux or centre of a new, more theoretically based film culture that was going to dominate in the 1970s and into the 1980s.

What was happening in the United States is that people were scrambling to catch up with Screen and read the writers Screen was translating and talking about. The year 1976 was a kind of annus mirabilis for English language serious film publications, something like seven or eight of the really important journals were started in that one year. Camera Obscura was one, and by then we had Film Criticism and Literature-Film Quarterly, and Ciné-tracts was starting – so many journals so quickly. Just by the number of serious film journals you could diagnose that the new theory culture was definitely here to stay. Was I interested in it? Of course, I was always interested in keeping up with how people were thinking about film. I was very interested in keeping up with the theory and was interested in being a promoter of it to some extent.

In what way were you a promoter?

RT: By arguing about it, teaching it, talking about it, and directing people to it. I was a big bibliographer, I had this 3 x 5 card cross-index of articles, journals, and topics that just kept getting bigger and bigger. But I was not myself a theorist, I didn’t write theory, and I didn’t create theory. I was interested in teaching it, and also interested in understanding its limits and not getting too far away from the film itself. I never wanted to do that.

Interesting that you make that point because it seems theory forces you to see something that you don’t want to see, or have you believe you’re seeing something that you’re not.

RT: That’s a very nice way of putting it.

But there is theory in, say, Durgnat’s writing but it’s almost as though it has the consistency of liquid.

RT: Yeah, Durgnat was not a slave to theory. He used to do this thing where he would develop a point and argue or lay out a position and then the next paragraph would start with, “But on the other hand …” That’s the kind of freedom you want, to be free of being bound, and he was quite conscious of that. I think he even used the word dialectic; he thought it was a dialectic to develop an argument that could go either way, could be both, or could be in between.

Which is exactly what happens when watching films. Out of the Past, for example, is an exercise in asking questions that can go either way: Is Mitchum looking this way or that way? Is this guy in trouble or not in trouble?

I like the scene in Out of the Past when a guy says to Mitchum, “Are you in trouble?” Mitchum says, “Why do you say that?” and the guy says, “Because you don’t look like you’re in trouble.”

And one of the things about your writing is that it does engage theory too, or theory-in-practice, like ‘here is the theory of such-and-such in a cartoon called Duck Amuck’, for example.

RT: Well, that brings us to the “Young Mr. Lincoln” piece that Ron Abramson, who is now Ron Abrams, and I wrote.[17] We wrote it when we were grad students at UCLA and it came out of a program we had there of visiting professors – one semester we had Brian Henderson, and Ray Durgnat was there for another semester. Anyway, that article came out of a semester we had with Dudley Andrew where Ron and I chose to do a seminar paper on Young Mr. Lincoln because, I think, the Cahiers article had just recently been published in English translation.[18] I had read it in French when it came out and people were sort of making noises about it. But Ron and I talked about it and kept finding things we were dissatisfied with what the Cahiers people were doing, what kinds of theory they were using, what kinds of conclusions they were coming to, and how they were using the film. We thought that maybe we could take a look at the collision of two kinds of theory: the political and cultural kind of Cahiers du cinéma post-68 and the kind of Cahiers du cinéma pre-68, which is to say mise en scène criticism. We used mise en scène analysis to critique the abstract theory and abstract claims that had been made, which was not an un-theoretical thing to do. It was a critique of a certain kind of theory using another. Well, I don’t think auteurism is a theory but by using mise en scène stuff to call into question more vague or physically unsubstantiated claims.

That was published in Ciné-Tracts but it started as a presentation?

RT: Yes, and then we proposed it to Ron Burnett, who was the editor of Ciné-Tracts at the time. Dudley Andrew was great because he marked our seminar paper and we said to him, “We’re thinking of getting it published?” Dudley said, “No, I wouldn’t bother, nobody’s interested in the Young Mr. Lincoln piece anymore.” “Okay”, we thought, but then we got it accepted at Ciné-Tracts and in the six months between Dudley telling us that nobody would be interested and when the issue of Ciné-Tracts came out, six articles on the Young Mr. Lincoln stuff appeared in different film journals.

How did you feel about the film theory that was coming out of Screen?

RT: I had skepticism about some of it, but more about what grew out of Screen or what it fostered, its children and grandchildren. I can remember someone who was very influenced by theory, who was going to write on horror films, and the thesis of the paper was that in horror films the horrible threats/creatures/phenomena are always phallic. A couple of us thought about this and by the end of the week we had a list of about fifty horror films where the horrors are not phallic, starting with The Blob [1958] on to The Green Slime [1968]. To me, that was a misuse of theory, or theory not supported by reasonable knowledge or reasonable scholarship of the films.

It was reductive?

RT: The claim was driven by theory rather than driven by the films themselves, the concrete evidence. That was one example of the problem associated with a kind of scholarship that is driven too far by theory, too far away from the case history, if you like, and to be ahistorical and – not to put too fine a point on it – not to know enough about what you are talking about. That was the kind of cautionary approach I had to theory.

But did you have any particular theoretical streams or approaches that you favoured more than others, that you thought were useful?

RT: If I had to start somewhere I would probably start with narratology and mise en scène. I probably did more with them and paid more attention to them than anything else, and, following on from that, probably hermeneutics. I wasn’t much on psychoanalysis. But psychoanalysis I treated with respect because my father was a psychiatrist; I wasn’t going to poach on his reserve.

Anyway, I was reading all of that stuff from Screen and Camera Obscura and Wide Angle and so on. It was a cultural period that ran into the ’80s and then was supplanted by the return of empirical history. The next big wave after the theory wave was the return to empirical history, which began in the ’80s and certainly occupied the ’90s, pioneered by people like Garth Jowett and Tino Balio.

To backtrack, you were teaching a number of film subjects in the mid-to-late ’70s, and also writing, and then in 1980 you come to Australia to take up a post at La Trobe University. How and why did that happen?

RT: I ran out of one-year, bottom-of-the-ladder teaching contracts at the end of 1978, or maybe it was in the middle of ’79 because that’s how semesters work in the US. I didn’t have anything lined up and I had sent out a lot of applications. I applied to anything I could see to apply for and then I got this tip from an old mate at La Trobe saying there was a position going and that it might be something for me to think about. That old mate was my mentor Bill Routt, who had already come [to La Trobe University] in 1977. Anyway, I sent off the application and I heard nothing at all, which is what I was hearing from all of my applications, and so I wrote it off.

But then I’d just come back from a road trip to see my family up in Oregon, and it was the 4th of July [US Independence Day] and the phone rings. I pick up and this voice with an odd accent asked me if I was still interested in being considered for the lectureship at La Trobe. I said, “Yes, I’m still interested,” and then this voice said, “And would you also be interested in being the Head of the Program?” I’m 34 years old and thinking, “It’s going to be a long time before I get an offer like this,” and so I said, “Yes, of course,” and he said, “Okay, we’ll will fly you over for an interview in two weeks time.” I didn’t have a passport, so I had to get a passport really quick, and they flew me over and I went through the selection committee and they decided that I would do.

I then met and talked to the three people who had been here for two or three years in the Media Centre of the School of Education and who had decided to break away and go into Humanities and form a stand-alone Cinema Studies program. They were Jeff Peck, Sam Rohdie, and Lesley Stern. After Humanities gave me the job, I sat with the selection committee and the big issue was whether Jeff, Sam and Lesley should be kept or whether they should be dumped and advertise for a whole new team because all of their contracts had reached an end. I still don’t know all of the history of this, but it was rather clear that a very strong part of the selection panel wanted to get rid of Peck, Rohdie, and Stern. We spent quite a bit of time talking about this and finally I decided it didn’t make sense to advertise for a new team because at least we knew who we had, and I couldn’t see us having a new cinema studies program with any ambition at all by dumping the guy who made Screen what Screen was in 1980. He was a major architect of the film culture we were in and proposing to teach. That just didn’t make sense to me and so I used whatever influence I had to keep them and fortunately we did.

But, in retrospect, it was also a strange and incomplete move because if you wanted to set up a major film studies program in Australia, why would you leave behind probably the outstanding scholar of Australian film history at that time, Ina Bertrand. Why wouldn’t you bring her in? And why would you leave Bill Routt, who has considerable historical credentials, over in Media Studies? In retrospect, that would have been a wonderful team but I didn’t see this at that time.

Anyway, I was appointed for three years in the first instance, which meant with conditions. At that end of that period, the program decided we’d rather elect our head or chairperson, which, being from Oregon and all, certainly seemed right to me, and we elected Sam Rohdie for a two-year frame. After that, until about 1996, I was elected over and over – not, I think, because I was popular but because nobody else wanted to wade through all the administration.

I could be wrong, yet my reading of Bill Routt inviting you was not only to have a close buddy here. He also wanted people he valued in film culture who had a pretty good idea of what a program might be like in a new university where things were beginning from the ground up. There must have been some vision for what possibly could be done at La Trobe?

RT: There was a sense of possibility but I have to say that I was totally naïve about coming to a place I’d not lived before, to a university I’d not taught at, and to a university culture I did not know. They offered me a new program to develop and that was a terrific thing to do and what I wanted to do, but I didn’t understand how difficult it would be and I didn’t understand the university culture I was getting into.

Do you mean the bureaucracy or politics of the place, because by that stage you had worked in quite a few universities?

RT: You have to remember I worked in a lot of universities at the bottom of the food chain. I had never chaired a university committee, I’d never been on a university committee, and I’d certainly never been a head of a department before I arrived here.

What about the oral history project at the AFI?

RT: That’s a little different to running a department. I really should have been much more wary than I was, but I jumped in and only slowly learned how difficult and complicated it was going to be. I may have been a very good choice for that committee to be put in as head of the program because I was an outsider and innocent and naïve. I also wasn’t an experienced academic in institutional terms. I wasn’t a player who knew how to pull all of the levers and so maybe they thought I wouldn’t cause much trouble or wouldn’t demand much. It may have been that kind of thinking back then. This is all speculation.

La Trobe seemed to have brought over a lot of people from overseas at that time?

RT: One of the things about the constitution of the Cinema Studies program – Peck, Rohdie, Stern, and Thompson – is that we were all foreigners, we were all from outside. The other three had the advantage of having been here for two or three years. Rohdie and Stern came from the British film culture, mostly Screen culture. Peck came from the University of Michigan with a more traditional American history background, not very theoretical film history, and I think his thesis was on World War II films. I came from another part of American film culture.

Another aspect of the make-up of the Cinema Studies staff from overseas is that we had foreign languages. Rohdie had French and Italian; Stern had French, I think; I had French; and Peck, can’t remember, but having received his doctorate from the University of Michigan he would have to have had one. As the decade developed, Routt had French and Urdu and Burnett had French. Not to say Australian trained staff didn’t: Rolando Caputo had Italian and maybe French, not sure; Lorraine Mortimer had French at a translating capacity level.

About that time, Asian cinema became an issue and we also had a position to fill. Bill and I decided to target Chris Berry, who was at Griffith University at the time and we heard that he might be interested in making a move. We got him and he was an excellent addition to the staff, and would have had an Asian language, probably Mandarin. So from the 1980s into the 1990s, the program was quite cosmopolitan in its reading and research capabilities.

When you arrived in 1980 your appointment kind of coincided with the New Hollywood. I don’t know if prescient is the right word but there is something about your appointment in 1980 that was in anticipation of what was going to happen, what students were going to be interested in, what film criticism and theory would focus on. Before you took up your appointment people here would have known you were dealing with contemporary Hollywood and another generation of auteurs like Clint Eastwood and John Milius and Blake Edwards. If we look at your film courses in the early ’80s, you were teaching Walter Hill and Edwards and Scorsese at times, and showing students films like The Unholy Rollers [1972], The Driver [1978], Mandingo [1975], Used Cars [1980], etc. These are not ‘classic Hollywood narrative cinema’ and so they pointed to something like a new beginning.

RT: Depends how we date and delimit the New Hollywood. From 1969, with Easy Rider? The group loosely and collectively called the Movie Brats – De Palma, Scorsese, Schrader, etc? Roger Corman’s crew? When I undertook that series of interviews in the middle of the 1970s for Film Comment, I consciously selected the New Hollywood as the central focus, people who had started to direct in the past two or three years or were to direct soon. I started with Paul Schrader, though I don’t think Schrader had directed yet, but he had written Taxi Driver [1976] and The Yakuza [1974].

Incidentally, I had been Schrader’s assistant editor when he was editing Cinema, and in fact the only other serious claim I can make to being involved in theory – and this goes back to promoting theory rather than producing it – was that I talked him into publishing a special section in 1972 called “Guide to Christian Metz”. That special issue included a glossary, my introductory article, “The Metz Is Coming”, and a translated excerpt from Language in Cinema,[19] which, as far as I know, are the first articles by and about Christian Metz in Anglophone film journals.

Anyway, I started my interview series with Schrader and then did Milius, who is a writer turned director, and then Eastwood. I had seen the first Eastwood-directed films, Play Misty for Me [1971], Breezy [1973], High Plains Drifter[1973], and The Eiger Sanction [1975] when Tim Hunter and I interviewed him in 1976. I went to the preview of Play Misty for Me at the Writers’ Guild one night in 1971 with a writer friend of mine and after the film in the lobby we were all standing around talking about it and I was the only person there who thought it was a really good and interesting film. Everybody else thought it was a piece of shit made by an actor. Having done the first two interviews for Film Comment by that time, I really was very interested in Eastwood’s work and I really wanted to talk to him about it; he was making The Outlaw Josey Wales [1976] at the time. I told a lot of my friends, who were on the fringes of the film industry, what I wanted to do and they all said, “Ah, Eastwood never gives interviews! You’ll never get Eastwood; just forget about it. Dream on!” Anyway, I sat down and crafted a letter to Eastwood. I included copies of Film Comment with the Schrader and Milius interviews and I wrote, “Dear Mr. Eastwood, I’m really interested in the films you’ve directed and I’d really like to interview you. I don’t want to interview you about being an actor, I don’t want to interview you about being a celebrity, and I don’t want to interview you about your private life. All I want to talk about is you directing the films and how you thought about them.” I threw it in the mail box and all of my friends knew that I’d made this pitch; they thought of this as a suicide mission that was never going to happen. Now you need to understand that in Hollywood at this time anybody who was somebody had a personal assistant. If you rang them, you’d get their personal assistant and they’d say, “Please hold the line for Mr. So-and-So,” and if they rang you the personal assistant would say, “This is Mr. So-and-So’s personal assistant, will you hold the line?” Anyway my phone rings three days later, I pick up and this guy says, “Hi, this is Clint Eastwood, when do you want to do the interview?” and I figure one of my wiseguy friends is taking the mickey, and I said, “Yeah sure, who is this really?” I made him convince me that he was Clint Eastwood. He made his own phone calls; I couldn’t believe it.

What I was saying is that your appointment coincides with the New Hollywood and no one in film studies in Australia was paying attention to it, at least not for another half decade. We just have to look at the contents pages of The Australian Journal of Screen Theory in that period to realise that no one had New Hollywood on the radar to write about. Yet look at what you are being asked to write on by Cinema Papers – Body Heat [1981], Southern Comfort [1981], Raiders of the Lost Ark [1981]. I think a wider scholarly interest in New Hollywood in Australia comes much later and it was ushered in by or localized to horror movies. So when you came here did you teach some of the stuff you were teaching in United States?

RT: It’s hard not to continue teaching from where you left off. When I got here, and as soon as we got the first semester off the ground after the shambles of the first two or three weeks, I had Jeff Peck, Sam Rohdie and Lesley Stern over to my house for an all-day meeting where we talked about what we wanted to do with the program. The starting point I suggested was that I didn’t think we should start looking at other models to imitate, but that we figure out what should be taught and how it should be taught. That was the starting point for discussion. At that time there was a rule in the School of Humanities that you were allowed to apply for no more than two new subjects for next year’s curriculum. I went to the Dean and said, “Listen, we are trying to set up a whole new program here, not from scratch but we want to be released from this requirement. We want to be able to propose as many new half units as we think we need.” He agreed and so we were allowed to pretty much nominate what we thought should be added to the curriculum.

Since the late 1960s I had done more teaching and enjoyed it, and learned a lot from it. By the end of the 1970s, people in a position to know were saying I was good at it – and not just to me. I liked structuring a teaching unit, fitting it into a curriculum, assessing utility to students, and moving toward larger units. But until the La Trobe offer, I had had limited scope. Suddenly, my colleagues and I had the opportunity to develop a teaching and curriculum program in all senses. It was wonderful; immediate feedback and interaction and not the isolation of writing. I threw myself into it, and got a lot of help and instruction from the people I was working with – not least the students.

You also mentioned on another occasion that you had Bill Routt come over from Media Studies to teach in Cinema. Was that because you were trying to bring him across or because of his particular orientations?

RT: Let’s be clear on this, Bill had been my mentor since I was 18 and was at university, so I was always talking to Bill and always trying to listen carefully and take his advice. I always wanted Bill in the program even though he was in the Media Centre in the School of Education. As soon as I could convince him, I had him teach just one half unit in Cinema Studies and built on that. It took six years until Bill finally decided to switch completely from the School of Education Media Studies to the School of Humanities Cinema Studies.

Bill and I would sometimes co-teach a course or half unit. I can’t remember which one but I can remember doing that, and I wasn’t only teaching new Hollywood cinema. I was also teaching topics like Film and Interpretation because hermeneutics was important. Bill was very good at pushing for a history course; he always had an under-graduate film history subject and he did very good things with it.

How did you start to grow the department and the program because then Ron Burnett, for example, came over and taught Cinema Studies?

RT: Okay, forgive me if I give a long and detailed answer, but a lot of us put a lot of work into developing the program, keeping it current, giving space for individual staff specialties and interests, while at the same time covering the field adequately. It’s an accomplishment I’m proud to have been a part of.

The first way we grew the department was because our student numbers were increasing, so we used that as an argument for more staff. We were first given tutors, then more lecturing positions. We were lucky and found good people as tutors and lecturers, in those first years we had Kim Montgomery, who went on to Australian Centre for the Moving Image, then Rolando, now also editing Senses of Cinema, and Sally Stockbridge, who went on to the Censorship Board and Channel Ten, if I remember correctly.

Regarding program development, as you already know Cinema Studies grew out of the School of Education’s Media Centre, and in 1979 became a stand-alone independent program in the School of Humanities. In that first year, Routt and Bertrand offered a history unit and a new first year subject, Introduction to Film Analysis, came on line. Other people from Media were also teaching in Cinema Studies: John Langer taught Popular Film Genres, Ian Mills taught Film Form, Ina Bertrand offered Australian Film History, Jeff Peck offered Non-Fiction and Non-Narrative Uses of Cinema, and Sam Rohdie offered National Cinemas, France as well as Italy, and he and Lesley Stern taught Soviet Cinema, and Lesley also taught Narrative and Realism in the Cinema. I think sample readings for 1979 included Christian Metz and Noel Burch.

Then in 1980 the Cinema Studies program began to have much more control over its structure and content. We began to think about the curriculum as having four overlapping and inter-related areas: theory, criticism, history, and national cinemas. I was very lucky to be with a group of remarkable people; the development of the new curriculum was very much a group effort, and I learned a great deal from my colleagues. New Cinema subjects in 1980 included Sam teaching Film History, I taught National Cinemas – US and Film Authorship, Lesley did Japanese Cinema. Theory in general and semiotics particularly received emphasis and that year’s reading included Peter Wollen, Andrew Sarris, Metz, and Perkins.

Then more new subjects in 1981. History of Film and Film Thought, listed under my name but I think Bill Routt and I taught it together, though he taught it on his own the following year. Lesley taught Alternative Cinema and also Film, Culture and Ideology. I taught Close Analysis, a unit that was originally Sam’s idea, to work on a single film for 13 weeks and apply various analytic approaches and methods. I also taught Film and Interpretation, a hermeneutics survey, and Current Problems in Film Theory. Lesley also introduced a unit on Point-of-View. Readings in 1981 would have included Gerard Genette, Vladimir Propp, Tzvetan Todorov, Stephen Heath, Manny Farber, Ado Kyrou, Jean Douchet, Stanley Cavell, Raymond Bellour, and Edward Branigan. In 1982, Sam offered Film and History, Jeff Peck introduced Film Industry and Conditions of Production, and also Introduction to Film Technique. Tino Balio, Garth Jowett, and Thomas Guback would have featured in the reading lists that year.

By 1984, Lesley had left and Ron Burnett, editor of Ciné-Tracts, joined us. He was extremely au fait with what was going on in film theory. He introduced the Psychoanalysis and Cinema unit that year, Sam Rohdie debuted National Cinemas – full stop. By 1985, Barbara Creed had joined the staff and she introduced Genre Studies and Film Theory, and a third-year unit on Film Theory, Sam introduced Australian Film 1945-1983. In 1986, Bill Routt officially joined Cinema Studies full-time and he introduced Construction of Film Culture; and that same year, Barbara introduced Feminist Film Theory. In 1987, Ron taught Documentary Cinema, Bill introduced Popular Film, and Sam brought in a unit on Michelangelo Antonioni. Then Ron Burnett had left by 1989, Bill introduced a pair of units – History of Film: Silent Cinema and History of Film: Sound Cinema – Barbara had a new unit, The Horror Film, and Sam’s two new units were Italian Neo-Realism and, separately, The Films of Pier Paolo Pasolini. So it was an extraordinarily busy decade of change and development.

Then in the next few years Barbara Creed left to become a professor at Melbourne University and Lorraine Mortimer joined us. She brought her sociology and French language skills, not to mention her enthusiasm as a teacher – you will know her books on Makavejev and Edgar Morin. These details are relatively accurate. La Trobe University’s records are not easily accessed or complete, so what follows relies on my creaky memory. Around 1995 or ’96 there happened a major shift: Bill Routt took early retirement and in that same period Lorraine Mortimer returned to the Sociology Department. In short order, we were able to add Geoff Mayer, then Felicity Collins to our staff. We elected Geoff as chairman of the program, to my relief, and I turned my attentions elsewhere. I developed a unit on Comedy, which worked well, one on Animation, which certainly had legs, and Anna [Dzenis] and I worked up a unit called Film Criticism [now Screen Criticism], which has a large writing workshop component, and which has run for probably 20 years now, largely due to its popularity with students.

To go back to 1980, how did you get involved with the local film culture? Was it through Tom Ryan and that he was he was writing for Cinema Papers or that he was teaching a film course at what was then known as Melbourne State College?

RT: Tom and I got together fairly early and it was through the steering committee of the Australian Screen Studies Association [ASSA] which I had been asked to chair in 1981, to set up the new organisation and organize a conference at the end of a year. Tom was on that committee with Jack Clancy, Rob Jordan, Brian McFarlane and David Hannan. I am certain that was when Tom and I got to know each other.

And what local film publications were you reading around that time?

RT: Australian Journal of Screen Theory, Cinema Papers, and then Continuum.

What were your impressions of the film scene when you got here, specifically film academia and film criticism?

RT: The impression was one of a kind of time shift: that things were happening here in film thinking and film culture that had already happened in the ’70s in the States and UK. I can remember when I got here in 1980 that there was a very energetic and established film teaching community in tertiary institutions. It’s hard to think of any tertiary institution – in Melbourne at least – that didn’t have at least one person teaching a film course. Ina Bertrand at La Trobe, Basil Gilbert at Melbourne, David Hannan at Monash University, Jack Clancy and Rob Jordan at RMIT, Brian MacFarlane was at one of the institutes of technology that’s now part of Monash, Tom Ryan was at Melbourne State College with Arthur Cantrill, Freda Freiberg, and Barbara Creed, to mention a few.

And there was a strong organized, experimental and avant-garde film scene; the Cantrills [Arthur and Corinne] for a start, who were always great activists for avant-garde film, and then the Super 8 groups. It was certainly a happening scene, not moribund or non-existent, and obviously people had been putting things together here for quite awhile, digging themselves in and getting teaching places going in universities and setting up various kinds of institutions.

On the other hand, there were “Toto, we’re not in Kansas any more” moments! I remember a Call for Papers which said, and I paraphrase, “Even on Jerry Lewis. Well, not really on Jerry Lewis.” And I thought, so much for the work of Robert Benayoun, Noël Simsolo, et al. There were parochial pockets in the film culture. Come to that, in university culture as well. For the first few years I was at La Trobe, or until Cinema Studies started churning out enough surplus profits to underwrite the deficits of the older departments which ran the School of Humanities, rarely a lunchtime conversation, faculty meeting, or whatever confab would go by without someone from a more traditional department joshing me about “Structuralism, ho-ho!” or “Theory, still teaching that, are you?” or “Not still having them read French stuff, are you?” I had known that Australian public culture back then was a bit more anti-intellectual than the US; what I hadn’t realised was that it reached into our university culture.

Film criticism? When I got here it was a very different situation, as far as I could tell with all the cultural innocence of a newcomer. It existed, certainly, but as I encountered it in an intellectual culture driven to prove that Australia – tyranny of distance, in all senses – was not a backwater, a culture thus driven by obeisance to the pursuit of theory for its own sake. Nothing wrong with that, but it did leave a vacuum. During the 1980s, I watched Adrian Martin turn this around. The icon of that was his article “Theory Weary”,[20] a great Tex Avery title; his work from early in the 1980s was to show that criticism could operate at the same level of seriousness and value that theory could and, implicitly, that it might be more interesting. Adrian was the instigator, the agitator who rallied the cause of criticism from the 1980s on; and he drew a great many writers and thinkers into his orbit. With the proviso that I was very much a local Victorian participant in Australian film culture, and realizing that the following comment does not include the work of many serious and valuable members of the film culture community, to whom I apologize and wish I had I had the wit and memory to include in this interview format, Adrian Martin’s work in carving out a place for criticism equal to that of the prevailing theory ethos was for me the most important development here from the 1980s into the 1990s, and a key factor in establishing the film culture we have enjoyed since then. There are many highwater marks along the way in this, and many distinguished participants. For me, the special edition of Continuum (vol. 5, #2) that Adrian edited in 1992 is second to none in marking a new intellectual regime in the area.

Participants included Stuart Cunningham, Geraldine Bloustien, Bill Routt, Barrett Hodsdon, Leonie Naughton, Alain Masson, John Flaus, Jodi Brooks, Ted Colless, Phil Brophy, Gabrielle Finnane, Raffaele Caputo, Tom O’Regan, Robert Sinnerbrink, Carol Laseur, Felicity Collins, and Vijay Mishra. It included the magnificent “Mise en scène is Dead, or The Expressive, The Excessive, The Technical and The Stylish” by Martin: I thought I was on top of the Anglophone and French literature at the interface of criticism and theory, but his piece humbled and instructed me.

You introduced Manny Farber to a few people – Rolando [Caputo] and Adrian [Martin], for example – and so it seems you had certain needs or polemics in your teaching in wanting to give really important things for people to know. I suppose that in teaching an American Cinema subject you would have put Manny Farber’s writing alongside certain films. But I don’t think that Farber’s writing was being taught, let along on reading lists for film courses anywhere else in Australia, nor was someone like Raymond Durgnat, another writer you’ve championed, and I assume that’s because once film studies started to be institutionalized here, in came theory in a very big way.

RT: In response to that, I would say that when I was in the States it was very important for me to study with visiting lecturers in criticism and theory. The UCLA film department had a committee with student representatives on it that made a decision every year about who to invite as a guest professor for a semester. I can remember being at one of those meetings and I was proposing and arguing to get Thomas Elsaesser invited because I was following his work …

Because you were teaching film noir?

RT: Probably. Anyway, my initiative did not get up because none of the students and none of faculty knew of Thomas Elsasser. We got Dudley Andrew or Brian Henderson or maybe even Durgnat instead, but that was fine because they were good value too. But what I mean to say is that even at UCLA at that time there was a gap between film culture and an ‘institutional’ film culture.

And this was when you were teaching film noir there? And you were teaching film noir to Paul Schrader?

RT: Schrader was not at UCLA; that was earlier at the AFI. But yes I did seminars on film noir at UCLA and at the AFI and Paul Schrader was at one of the AFI seminars in 1970s.

What is your interest in film? I know you are interested in animation, film noir, Robert Mitchum, Eastwood, New Hollywood, and so on and so on, but I’m not asking about that.

RT: That’s hard. I don’t question my interest in film. I don’t think about it. One way or another I’ve just been interested in film, passively until university, then more systematically and more actively from university on.

What do you write about? I’m not talking about a subject or topic or person, but what are you writing when you write on film?

RT: I don’t know if it’s this, but I think everything comes out of description. To have analysis the only way is to move from description, and that’s how I try to think about and organise things.