Harold Shaw parted ways with the movie magnate I. W. Schlesinger in October 1917, after an acrimonious personal dispute, and immediately set about organizing his own film production company. Shaw poached leading production staff from Schlesinger’s African Film Productions at Killarney in Johannesburg, and signed up Schlesinger’s bitter rivals, A. M. Fisher and sons of Cape Town, to distribute his movies to theatres independent from Schlesinger’s African Theatres Trust.

On 5 December 1917, The Cape Argus carried the following news report from Johannesburg: “The Harold Shaw Films Production, Ltd. have [sic] been formed. The company leaves for Cape Town to-night and operations will be started on Monday, all material having arrived from the States last week. It is hoped to show the first production in February. Fisher’s Bioscope will handle the films.”

Harold Shaw had decided to base himself in Fisher home territory at the Cape of Good Hope, which boasted within twenty kilometres a great variety of urban architecture and spectacular scenery—including beaches suitable for sand deserts. He had found a studio overlooking Sea Point in Cape Town in a former tram shed “above the Tramway Company’s Terminus … remarkably free from South-easters, and in a beautiful position”, and had ordered the requisite cameras and other equipment from the United States (The Cape Times, 13 December 1917, 8).

Announcing the launch of “Harold Shaw Film Productions Ltd.” at Sea Point, the Cape Times added that “It is the intention to produce … photo-plays dealing mainly, but not necessarily exclusively, with South African subjects. The first long film is to be a comedy-drama, and this will, it is expected, be screened next February, the handling of the films being in the hands of Messrs. Fisher, who intend touring the principal towns of the Union” (The Cape Times, 13 December 1917, 8).

Shaw chooses crew and cast

Shaw was joined by other dissatisfied people from the Schlesinger trusts: his wife Edna Flugrath, co-producer Ralph Kimpton, photo-lab manager Henry Howse, and leading actor M. A. Wetherell. From England, Shaw recruited his old colleague cinematographer Ernest Palmer, whom The Cape Times described as having “photographed all the principal pictures that Mr. Shaw has made both in America and England” (The Cape Times, 13 December 1917, 8). Both Howse and Wetherell had sons fighting on the Western Front in Europe (The Cape Times, 13 December 1917, 8; Stage and Cinema, 27 January 1917, 78, 24 February 1917, 2). Palmer came directly from an Allied military attachment that was filming the war in Europe. Such patriotic credentials strengthen the argument that Shaw’s break with African Film Productions was motivated in part by repugnance at Schlesinger’s compromised stance with regard to the war.

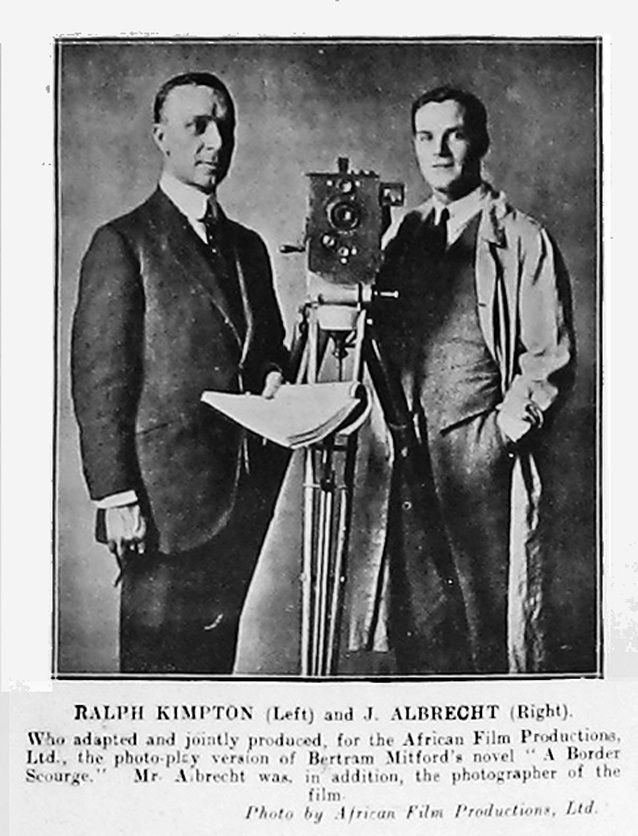

Ralph Kimpton (Fig. 3.1) had personal reasons for breaking with Schlesinger. He had once been a theatrical producer for George Alexander’s company at the St. James’s Theatre in London, and had directed plays on both sides of the Atlantic. With credits as an “associate producer” on De Voortrekkers and a “co-producer” of A Border Scourge for African Film Productions, he had been earning £65 a month as AFP’s assistant producer in charge of requisitioning of stores. But he appears to have had a drink problem, and had been accused of sloppy work in filling out the required forms. Schlesinger upbraided him that “if the requisitioning process was not carried out in detail he would turn the business into a [word deleted] laundry.” In return, Kimpton complained “that the spying system which existed at Killarney and with the African Films Trust made him dissatisfied with the African Films [sic] Production” (The Cape Times, 13 December 1917, 8; The Rand Daily Mail, 20 April 1918, 6).

Henry Howse (Fig. 3.2)—“I’m a cinematographer, one of the first to go in for the game”—had entered the film business through a “connection with the La Lumière brothers of France” that he dated as far back as 1894 (Stage and Cinema, 24 February 1917, 2). The 1901 England Census identifies Henry C. Howse, age thirty-three and born at Sharnford in Leicestershire, as a photographer and bookbinder living at Roydon in Norfolk. In 1911, he was based in Penge, Kent.

Although Howse had joined the Salvation Army and was probably responsible for the organization’s prescient interest in cinematography (which began in 1897), he was unable to galvanize its London headquarters into setting up a cinematographic department until 1903, during which time the initiative had been seized by its Melbourne branch. A self-styled “expert in cinematographic science,” Howse recalled building his own movie camera and filming Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee of 1897, when the longest filmstrip obtainable was only forty feet. He accompanied and filmed Sir Thomas Lipton’s three unsuccessful bids for the America’s Cup in 1899, 1901, and 1903. In 1903, he became the Salvation Army’s movie cameraman, and made numerous films of up to six minutes around Britain and overseas, including General William Booth’s pilgrimage to Palestine and the Prince of Wales’s visit to India in 1905-06. In 1907, he accompanied Ernest Shackleton’s expedition to the Arctic, during which he filmed icebergs from the end of a plank attached to the ship.

After the Salvation Army closed its London film unit in 1908, Howse continued as a freelance, filming in thirty-five different countries over the years, including Tibet and China. (He even claimed to be a citizen with a Chinese name, free to travel anywhere.) By 1916, he had made two movies with his own production company in England, Meg of the Slums and The Stronger Will, and the following year Schlesinger induced him to come to Killarney studios, where he processed film stock as “one of the most competent dark-room and works managers” (Stage and Cinema, 24 February 1917, 2; “Henry Howse”; The Cape Times, 13 December 1917, 8;The Rand Daily Mail, 20 April 1918, 6; Hammond 2004).[1]

Ernest G. Palmer was a Kansas-born cinematographer who, like Harold Shaw, had migrated from Edison and IMP to London Films. His first British motion picture credit was for Ivanhoe (dir. Herbert Brenon, 1912). When London Films began to falter, Palmer moved on to aerial cinematography for the British War Department, using aeroplanes specially brought over from France (The Cape Times, 13 December 1917, 9). His credits as a cameraman-director included the 1250 feet documentary Fighting the German Air Raiders (1916). According to the Cape Times, much of his work was “done under the supervision of Mr. D. W. Griffith (of ‘The Birth of a Nation’ and ‘Intolerance’ fame) at the behest of the combined war offices of Britain, France and America” (The Cape Times, 13 December 1917, 9; “Ernest Palmer”). Rachael Low quotes from a letter from Palmer published in The Bioscope on 14 October 1915: “[T]he more realistic and natural the lighting is, the more convincing the scene will be, and if producer and photographer can work together to make the lighting and atmosphere as natural as possible, the best results will be obtained” (Low 1950, 148-49). It is unclear how Howse and Palmer divided the camera work between them on Shaw’s Thoroughbreds All and The Rose of Rhodesia, but in the publicity materials Howse receives all the credit for the latter.

Yorkshire-born Marmaduke (“Duke”) A. Wetherell (Fig. 3.3) began his career overseas as a frontier policeman in the Bechuanaland Protectorate (Botswana). Returning to England, he acted in northern repertory theatres and spent a couple of years in North-Western Rhodesia (Zambia) as a pioneer farmer at Choma (Macmillan 2005, 365) before taking to the stage again in 1912 with Leonard Rayne’s South African touring company. He was “loaned” to AFP in 1916, appearing as a lead character in most of their films, and played an active role in the production of A Border Scourge in Swaziland over Christmas and New Year of 1916-17. According to one report, “Duke” had got on splendidly with the sage old Queen Mother of the Swazi, Labotsibeni (Stage and Cinema, 27 January 1917, 78).

Another actor of note who appeared in The Rose of Rhodesia was Howard Wyndham, scion of a famous theatrical family which owned Wyndham’s Theatre in London. While other actors were recruited from Cape Town theatre companies, two amateurs stand out as having been chosen specially by Harold Shaw Film Productions: “Chief” Kentani and “Prince” Yumi, both of whom feature prominently in The Rose of Rhodesia. It is not known how they were recruited. Apparently father and son in real life, their ethnic background was Mfengu (Fingo).

The spirited and sympathetic performance given by Yumi in the film suggests that he was a Mfengu labour migrant or student from the Ciskei or Transkei regions who caught the eye of the filmmakers in Cape Town and persuaded the filmmakers to follow him to his father’s house near the Kei river. While Kentani does not appear on lists of Mfengu chiefs, it was the name of a hill and colonial village (Centane) in the Butterworth district of the Transkei, prestigious by virtue of being where Mfengu soldiers, with British support, had fought off Gcaleka and Nqaika Xhosa attackers in February 1878. The old man Kentani, who was probably a headman rather than a chief, clearly associated himself with the place or the battle; whether he came from there is an open question. The fact that The Rose of Rhodesia was filmed at the Bawa Falls, which also lies in the Butterworth district, suggests that the Yumi and Kentani either had a homestead in the vicinity or were on particularly good terms with the local headman.

Kentani’s possible association with the Cape Frontier War of 1877-78 is supported by a claim made in publicity materials for the film that he was “ brother of the man who started the last Kaffir War” (The Bioscope, 25 September 1919, 21). That man was Ngcayecibi, a Mfengu headman living on the Gcuwa tributary of the Kei, who in August 1877 held a protracted wedding celebration which was gatecrashed by Gcaleka Xhosa neighbours, who refused to leave after being told that the beer had run out. They were driven back across the Gcuwa stream, one of the Gcaleka men dying in the fray; three days later, a thousand Gcaleka attacked the Mfengu, triggering the ninth and last Cape Frontier War.

The Mfengu, originally refugees who had fled the expanding Zulu kingdom to seek shelter among the Xhosa, had become productive peasants. Favoured and given land by the British colonialists, they were despised as “dogs” by their former Xhosa masters. Although they had no paramount chief, their main military leader, Veldman Bikitsha, visited England in 1889 and told Queen Victoria: “[W]e have never feared a white man and have never lifted our hand against any of your people.” By 1911, the Mfengu numbered as many as 350,000, and Christian-educated Mfengu teachers and clerks had spread as far north as Rhodesia (Ayliff and Whiteside 1912, 63-64; Mostert 1992, 1249-51).

Pre-production of The Rose of Rhodesia

Reviews of The Rose of Rhodesia in the British cinema trade press in 1919 highlighted several deficiencies in the writing of its scenario:

At the start the impression is given that there is to be strong drama founded on a conflict between the interests of the natives and those of imperialism. But, in reality, the “native question” does not develop. The producers have carefully avoided the danger of giving offence to either partisan side … [and] have left a story rather devoid of “punch”. (Kinematograph Weekly, 6 November 1919: 115-16)

The story of the film is thin, conventional and rather clumsily constructed, but the gorgeous African landscapes against which, for the most part, it is set, invest the plot with an interest it would not otherwise possess …. One rather wishes, in fact, that Harold Shaw, who produced the film, had chosen a plot which would have made the natives the central features of the play. (The Bioscope, 6 November 1919: 99)

Harold Shaw was used to adapting other people’s writing for his scenarios. In the case of The Rose of Rhodesia, probably for the first time, he originated the story as well as the final production, which was reported as being “under the personal supervision of Mr. Shaw himself” (The Cape Argus, 20 March 1918, 7). Though it began as an adventure movie about a “native rising,” Shaw’s scenario degenerated into a conventional diamond-heist yarn. What made the movie remarkable was its sub-plot about a friendship between two young men, one white (Jack Morel, the missionary’s son) and one black (Mofti, Chief Ushakapilla’s son, played by Yumi).[2] The latter, of course, had to die tragically so as to release the white youth into the arms of the white girl (Rose Randall, played by Edna Flugrath).

The diamond heist plot, which had featured in South Africa’s first drama movie The Great Kimberley Diamond Robbery (1911), was here combined with the suggestion of a “native rising”: Ushakapilla (played by Kentani) commissions his people to steal diamonds to buy guns for an uprising—or simply to buy more land? The confusion is introduced by the explanation that his original grievance against the colonial authorities was their refusal to allow him “more land on the other side of the Zambesi” (The Cape Argus, 25 March 1918, n.p). (It is unclear whether Ushakapilla’s “Northern Rhodesia tribe” [The Cape Argus, 25 March 1918, n.p], resided in the south of what is now Zambia or in the north of what is now Zimbabwe)

This dilution of the “native rising” theme may be attributed to an understandable failure of nerve on Shaw’s part in the face of white settler sensibilities and wartime colonial censorship. The issue of land was topical in 1917 throughout Southern Africa because of recent colonial commissions that had divided the land into large white-owned areas and small reserves for blacks. But Shaw’s inspiration was probably more literary than political. John Buchan’s novel Prester John, an international bestseller since its publication in 1910, features a black clergyman named Reverend Laputa, who tries to lead a pan-African revolt that join Zulu and Swazi before spreading northwards to the people of the Soutpansberg in the northern Transvaal, who have been stealing diamonds to finance the purchase of guns from the Portuguese (Stotesbury 1993). The novel echoed the moral panic of 1906 during which white settlers had feared that the Bambatta rising among the Zulu would spread as far as the northern Transvaal and even cross the Kalahari to link up with another revolt in German South-West Africa. Buchan also played on fears about the so-called Black Peril: sullen assertiveness by black migrant workers and their potential leaders among the intelligentsia, particularly the “Ethiopianists” who had broken away from Western mission churches.

Shaw’s choice of genre for The Rose of Rhodesia could equally well have been inspired an as-yet unpublished novel by Heaton Nicholls, an author and politician based in Natal. Nicholls completed the (longwinded and poorly written) manuscript of Bayete! Hail to the King in 1913, but later claimed that he had been reluctant to publish it because it was too incendiary. The novel was eventually published in 1923 by Allen & Unwin as the author’s “note of warning” of potential black revolution to white South Africa (Reed 1950, 54). Nicholls had based his novel on his experiences of resistance to poll taxation by Ila people of North-Western Rhodesia (now Zambia) in 1907-8, to which he added Zulu or Zuluesque and Black Peril tropes obviously modelled on Buchan’s Prester John. “Duke” Wetherell, who had once also been a settler in Ila territory, was quite possibly an acquaintance of Heaton Nicholls with access to the unpublished manuscript. Wetherell would have been on hand in Cape Town in late 1917 to assist Shaw in drafting the scenario of The Rose of Rhodesia.

Filming The Rose of Rhodesia

Location shooting for The Rose of Rhodesia appears to have taken place in January and February 1918, followed by studio shooting and editing at Sea Point. On 18 January 1918, The Cape magazine remarked that Shaw’s company had not yet been seen filming at the Sea Point studio (The Cape, 18 January 1918, 3). On 16 February, The Cape Argus gave the first report that The Rose of Rhodesia was rapidly nearing completion, and announced on 2 March that the film had been completed. Even so, the newspaper reported some days later that Shaw was still “working hard and under great difficulties to get the ‘Rose of Rhodesia’ into shape” at his “fine studio” in Sea Point (The Cape Argus, 20 March 1918, 7).

It is more difficult to interpret the details of the publicity material given to the London trade press, which claimed that the Bawa Falls, where The Rose of Rhodesia was filmed on location, were “on the border of Zululand” and that its African stars were the “ruling chief of the Fingo tribe, together with his son, Prince Yumi” (The Era, 29 October 1919, 18). Still more fantastic was the boast that the crew had taken six weeks to trek to the falls, two hundred miles from the nearest railway, “so rough was the country through which they had to pass” (The Era, 29 October 1919, 18).[3] The Era furthermore claimed that “The natives who appear in the production were specially trained for their parts by Mr. Shaw. None of them could speak more than a few half-broken phrases of the English language. As payment for their services they were given tobacco, fancy wire, beads, sweets, etc.” (The Era, 29 October 1919, 18). A hundred metres high and two metres wide, the Bawa Falls stand on the Qolora river at Mnquma in the Butterworth district, far from the border with Zululand. The identity of the falls in the film can easily be confirmed by comparison with a modern photograph (Fig. 3.4). Access by road was doubtless difficult in early 1918, particularly after the rains, but six weeks must surely refer to the duration of the whole location shoot, including travel. Payment in goods such as tobacco, meanwhile, would have fully satisfied few Mfengu, who desperately needed cash to buy store goods and pay taxes.

The interior shots of a bar and trading store, and exterior shots of tin-roofed buildings, must have been taken in and around the Sea Point studio. Adverse comments by London reviewers on the interior lighting in The Rose of Rhodesia and Thoroughbreds All suggest that the Sea Point studio relied on inadequate natural light or weak electrical illumination, and it is clear from the way that the wind is clearly blowing both in the bar scene and at the Randalls’ home that some of the indoor sequences were shot outdoors.[4]

Located on a peninsular subject to cloudiness and storms, Cape Town suffered much greater vagaries of weather than Johannesburg, which generally enjoyed clear blue skies. As for electrical lighting, the power supply should have been sufficient since the studio shed had previously serviced tramways. But Shaw Productions had evidently not invested in the Klieg intense carbon arc-lights that were revolutionizing film production overseas at that time by adding “significant black and white values, and [giving emphasis] to feelings expressed by movement, and by picking out details of characters” (Carter 1930, 44). Though it was also true, given local fluctuations in electrical supply, that for many years to come Klieg lights “wavered, were not as clear as sunlight, and the lamps took too much time to arrange” (Chaplin 1964, 167).

Filming Thoroughbreds All

Harold Shaw Productions managed to complete at least one other movie during its short existence at Sea Point, though it is unclear whether it was ever shown in South Africa. Thoroughbreds All was a five-reel comedy starring Wetherell as Bishop Weston, Prince Russell as Father Cassidy, and Jack Lurie as Rabbi Levy—three jolly clerics who, having condemned betting from the pulpit, stealthily bet on the racehorse owned by the sons of the bishop and the rabbi. The initial credits satirically describe the film as “A Reply to D. W. Griffith’s ‘Intolerance’” (The Bioscope, 6 November 1919, 99). When shown in London at the same time as The Rose of Rhodesia in November 1919, it was described by The Bioscope as a farcical send-up of puritannical prejudice, with some spirited acting, particularly the Jewish burlesque of Jack Lurie. The photography was described as “excellent, albeit the studio scenes suffer from insufficient lighting” (The Bioscope, 6 November 1919, 99).

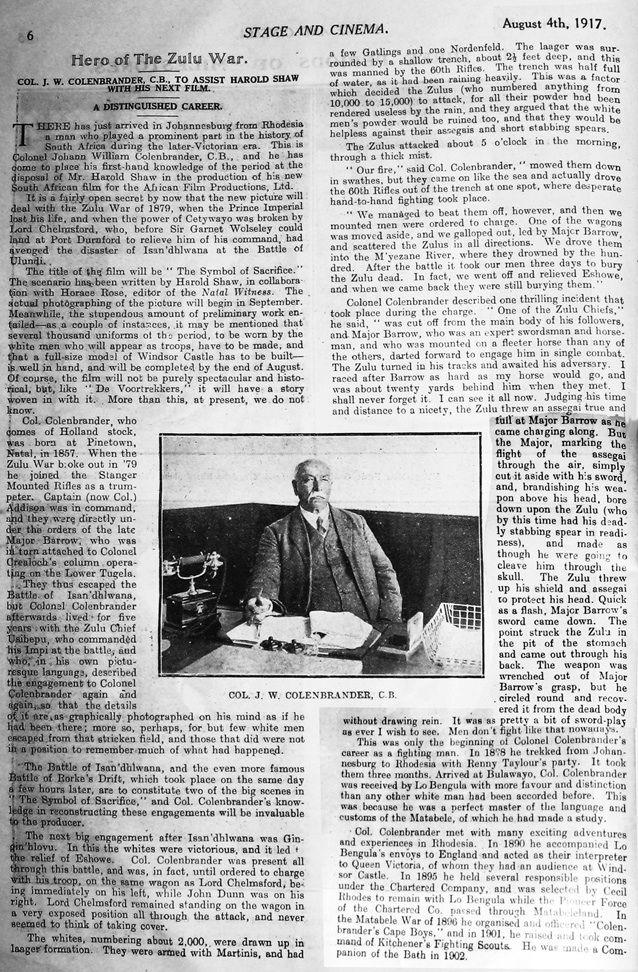

Meanwhile, African Film Productions went ahead with the production of The Symbol of Sacrifice, now directed by Joseph Albrecht with assistance from Schlesinger himself. The filming suffered from “the wettest summer on record” and a public relations disaster. On 10 February 1918, Colonel Colenbrander (Fig. 3.5), a famous old colonial adventurer, and two white veterans returned from the war, were drowned after Colenbrander insisted that he be filmed crossing a swollen river on horseback (Stage and Cinema, 26 January 1918, 4, 15, 16 February 1918, 7; The Cape Times, 6 March 1918, 7).[5]

Advance publicity and initial distribution of The Rose of Rhodesia

The Rose of Rhodesia was boosted by advance notices in the Cape Town press: “A brilliant super-film play. No battle scenes; no heart-stopping, blood-curdling, hairbreadth escapades. And no sex problems or ‘false lover’ plots” (The Cape Argus, 19 March 1918, 1). Such promises could well have dented the enthusiasm of Fisher’s usual customers, who were used to more salacious fare.

On 23 March, the Saturday edition of The Cape Argus announced the premiere of a seven-reel film titled The Rose of Rhodesia, to be screened that evening at 8.15 in the City Hall: “The photographic quality of the production will be an outstanding feature, having been attended to by Mr. Henry Hawes [sic], who was responsible for the filming of the ‘Voortrekkers’” (The Cape Argus, 16 February 1916, 9, 2 March 1916, 9, 20 March 1918, 7, 23 March 1918, 9). The Cape Argus, The Cape Times, and, subsequently, Johannesburg’s Rand Daily Mail all responded positively to the film. As significantly, the film was completely ignored by other publications, such as the weekly magazine The Cape and the daily Star of Johannesburg. The editor of The Cape noted on 10 May 1918 how civilly he was greeted by Schlesinger at a private viewing of AFP’s The Symbol of Sacrifice (The Cape, 10 May 1918, 23). The conspiracy of press silence around The Rose of Rhodesia was undoubtedly in deference to Schlesinger and his business interests.

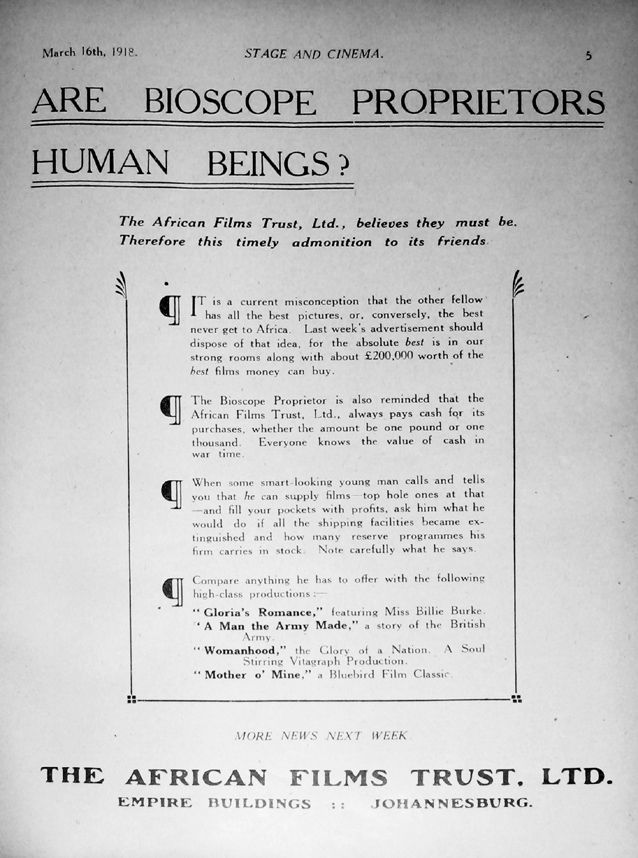

Schlesinger’s African Films Trust began a press advertising campaign in March-April 1918, aimed at small-scale “bioscope proprietors and their patrons”, operating in community halls, to stamp out the rival Fisher film distribution network. The campaign began innocently enough in the first week, advertising the superior quality of AFT wares imported through its New York and London offices: “No Company operating south of the Equator possesses greater buying facilities” (Stage and Cinema, 9 March 1918, 5). The second week’s advertisement (Fig. 3.6) was directly targeted at young Joe Fisher, the Fishers’ most effective salesman:

ARE BIOSCOPE PROPRIETORS HUMAN BEINGS? The AFRICAN FILMS TRUST, LTD. believes they must be. Therefore this timely admonition to their friends.

It is a current misconception that the other fellow has all the best pictures, or, conversely, the best never gets to Africa.

… When some smart-looking young man calls and tells you he can supply films—top-hole ones at that—and fill your pockets with profit, ask him what he would do if all the shipping facilities became extinguished and how many reserve programmes his firm carries in stock (Stage and Cinema, 16 March 1918, 5; The Cape Times, 16 March 1918, 9).

The next week’s African Films Trust advertisement was headed: “Discard all boasts and time worn adjectives of the film suppliers who would have you imagine they can revolutionise the business”. Somewhat disingenuously, given that Schlesinger owned all the cinemas in South Africa, it added: “When you are doing business with us, you are not doing business with a competitor. We do not show pictures, we import them for those that do” (Stage and Cinema, 23 March 1918, 5). The fourth week’s advertisement continued in like vein: “MR. BIOSCOPE PROPRIETOR, don’t allow yourself to be deceived into hiring films from the first person peddling competing stuff” (Stage and Cinema, 30 March 1918: 5). The Symbol of Sacrifice was clearly positioned to be the rival that would wipe out the competition of The Rose of Rhodesia, with the African Films Trust achieving pre-emptive bookings and charity showings in places like the Johannesburg Town Hall (Stage and Cinema, 6 April 1918, 11).

On 19 April 1918, the libel cases of Harold Shaw and Ralph Kimpton versus I. W. Schlesinger came before Mr Justice Ward in the Witwatersrand Division Supreme Court. Shaw was suing for ?5000 for slander, while Kimpton was suing for ?1000. A lot of dirty washing was aired in court, showing Schlesinger to be unreasonably choleric, abusive and profane, and a control-freak who tried to drive his employees to work as hard as he did (The Rand Daily Mail, 20 April 1918, 6). (A biographical essay on Schlesinger records that on one occasion he kicked a large tray of tea cups and milk jugs into the air, “with a highkick that would have done credit to a ballet dancer” because he despised the custom of interrupting work time for mid-morning tea. The author adds that “His bark was nearly always worse than his bite. But sometimes he bit and bit hard.” [Cartright n.d.: 185-86]).

However, the first day in court was followed by “discussion at the weekend”, and then by an announcement on 22 April that “Action against Mr Schlesinger [has been] withdrawn”. Presumably, Schlesinger had made ex gratia payments that satisfied Shaw and Kimpton. The announcement was carried in the Rand Daily Mail the following day. In the very next column of the newspaper, a press notice drew attention to the fact that The Rose of Rhodesia was due to open at Johannesburg Town Hall on Saturday 27 April.

The Fishers underlined their triumph by also playing at the Town Hall the Empire patriotic film Canada Spreads Her War Wings, accompanied by “specially selected music by a full orchestra” under the baton of one of the Fisher sons. But Schlesinger struck back on 1 May by liquidating and taking over the assets of the independent Apex film company, leaving the Fishers as the sole film distributors rivalling the African Films Trust (The Rand Daily Mail, 23 April 1918, 5; 25 April 1918, 10; 2 May 1918, 3).

The struggle between the Fishers and Schlesinger reached its peak in June 1918, when the Fishers announced that they would be showing Metro’s Romeo and Juliet at Johannesburg Town Hall on 15 June. AFT countered by digging out Fox’s rival (and rather lurid) Romeo and Juliet, starring Theda “the Vamp” Bara, to open at the Coliseum Theatre on 14 June. The two sides engaged each other in a propaganda war. The Fishers boasted of “absolutely no connection with the Theatres Trust, Films Trust or any other trust except the Public Trust” (Gutsche 1972, 153). AFT claimed that its New York representative had rejected the Metro film as unsuitable. The Fishers rubbished this by replying that Joe Fisher had bought the option for its African rights from Metro twelve months previous, before the AFT agent could have even considered it (Gutsche 1972, 154).

The battle between rival versions of Romeo and Juliet raged on through July 1918 in Cape Town, where the Fox film was shown at the Majestic and the Metro version at the Railway Institute. But now, while rumours of amalgamation between the Fishers and the African Films Trust were “strenuously denied in print”, negotiations did indeed take place (Gutsche 1972, 154). The Natal Mercury kept a wary eye on this further “trustification” of the entertainment industry: “On the 25th July, it was announced in Durban newspapers that Mr. Schlesinger … had acquired the firm of Fisher’s and that it would cease operating as independent” (Gutsche 1972, 155). Old man A.M. Fisher retired on ?50 a month pension, while his three sons became Schlesinger employees (Gutsche 1972, 155). At the end of 1918, Schlesinger’s entertainment magazine, now titled Stage, Cinema & S. A. Pictorial, crowed: “The year has once again proved that a cheap, efficient and satisfactory film can only be run in this country under centralised control” (Stage, Cinema & S. A. Pictorial, 21 December 1918, 20).

There was nothing now to keep Harold Shaw and Edna Flugrath in South Africa, particularly as regular shipping back to Europe was resumed with the ending of the war. They had tried to survive in Cape Town by combining with the Leonard Rayne company in a stage play at the Opera House, The Wasters, described as “a biting denouncement of the evils of divorce”. Though directed and stage-managed by Shaw, and featuring Flugrath in a lead role, it was at best a qualified success, and finished after a short run in early July 1918 (The Cape Times, 1 July 1918: 4, 9 July 1918, 6; 5 July 1918, 6; The Cape, 12 July 1918, 27-8).

Conclusion

By the terms of his agreement, Harold Shaw was to have directed Symbol of Sacrifice but soon after the launching of its production late in 1917, he left the employ of African Film Productions for a variety of reasons. Shaw then became associated with the Fishers—then in open opposition to the Schlesinger companies—who sponsored his production of a local drama called The Rose of Rhodesia in an old tramway shed at Sea Point, Cape. This film in which Edna Flugrath and M. A. Wetherell played the leading roles, was of very poor and amateurish quality and, though loudly boosted by the Fishers with the collaboration of the Press, survived only a few showings at various Town Halls during March-April 1918. In Cape Town, a disappointed audience adopted a truculent attitude at its conclusion. (Gutsche 1972, 316)

Gutsche’s statement seems to have been based on an oral tradition. She had used oral as well as newspaper sources for her 1948 doctoral thesis upon which her 1972 book was based, and acknowledged having interviewed surviving members of the Fisher family. Since she was herself an employee of the African Films Trust at the time she wrote the thesis, it would be surprising if she had not picked up some of Schlesinger’s own prejudices—regardless of the fact that she never formally interviewed her employer.

The plot of The Rose of Rhodesia was mundane and missed golden opportunities, and the lighting of interiors was not up to scratch. But far from being amateurish, as Gutsche claims, The Rose of Rhodesia had a cast and crew that had previously worked on—and subsequently were to work on—hundreds of American and British movies. The truculence of its Cape Town reception, if true, may refer to the expectations of an audience that associated Fisher’s films with risqué sexual material. As for its failure to be widely exhibited in South Africa, this may be most fairly attributed to its distribution being blocked by the Schlesinger monopoly in South African show business.

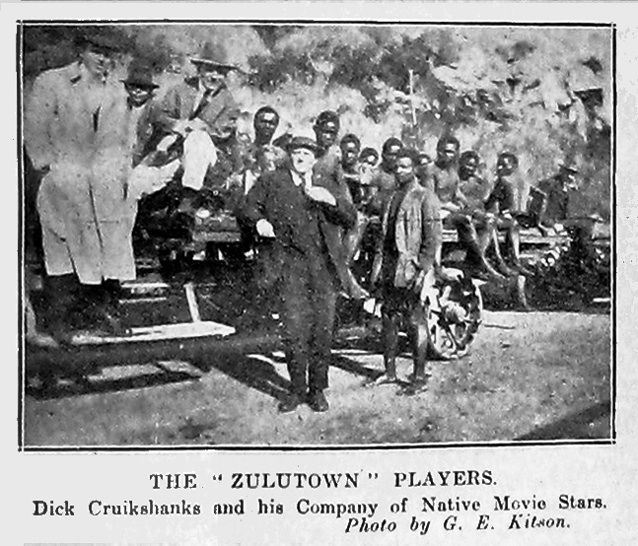

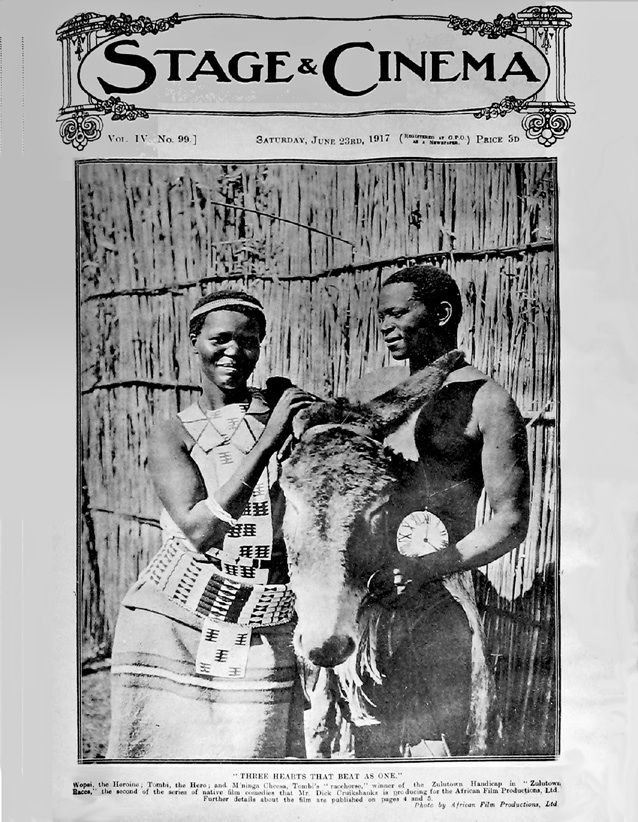

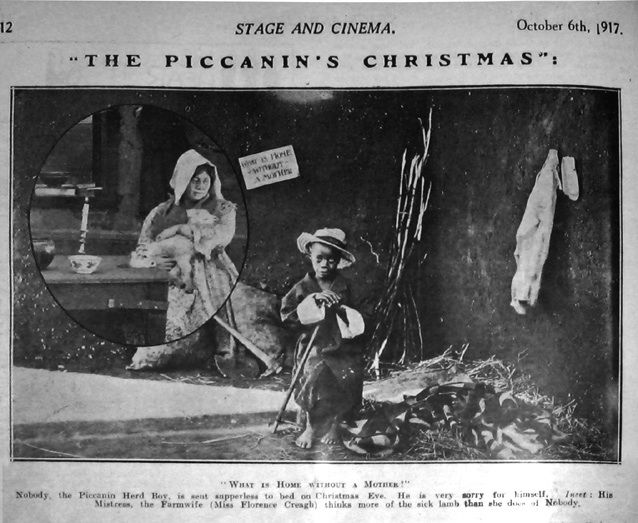

Harold Shaw’s significance for the history of South African cinema is greater than merely his involvement in The Rose of Rhodesia. Films made by Shaw and others during his period in South Africa display a more sympathetic attitude towards Africans, as both performers and protagonists, than would be seen for many decades in South African cinema. Shaw’s sub-plot of mutually friendly black and white lovers remained in The Symbol of Sacrifice even after he had left that AFP production. AFP subsequently made a number of virtually all-black movies with African heroes and heroines, albeit designed for white audiences and somewhat patronizing as well as Hollywood-inspired. The Chaplinesque Zulutown Races (dir. Dick Cruikshanks, 1917) featured an attractive couple of lovers (Figs. 3.7 and 3.8). The Piccanin’s Christmas (written and directed by Joseph Albrecht, 1917) was a cute children’s tale featuring a bright little herdboy and a nasty white witch who turns out to be his more kindly employer on the farm (Figs. 3.9 and 3.10).[6]

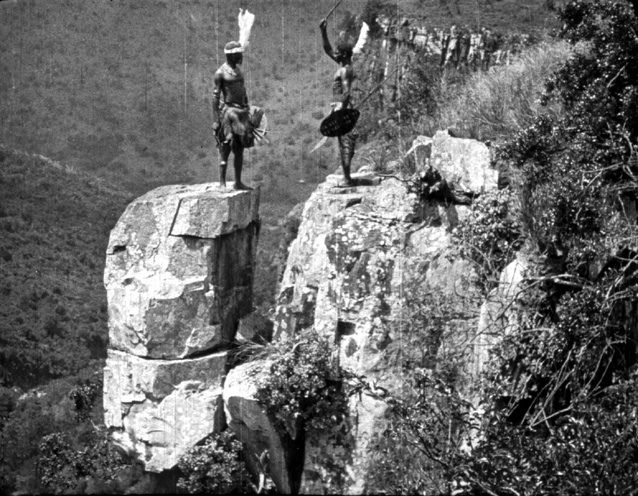

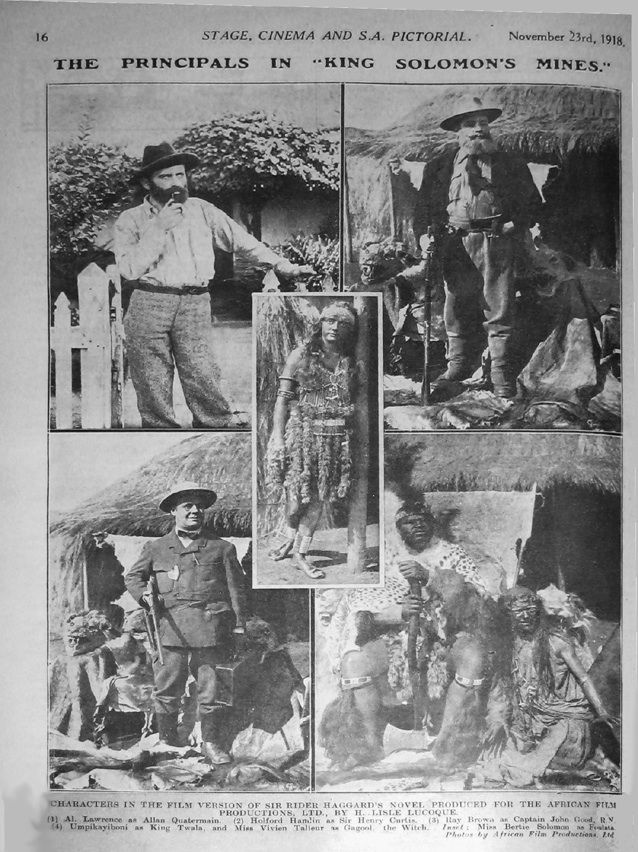

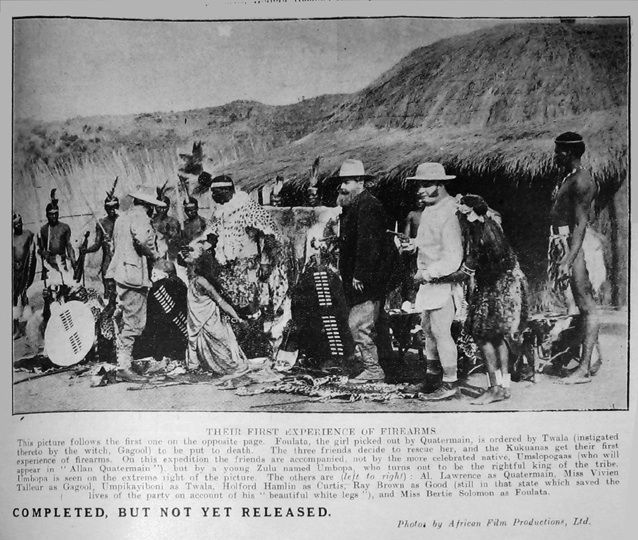

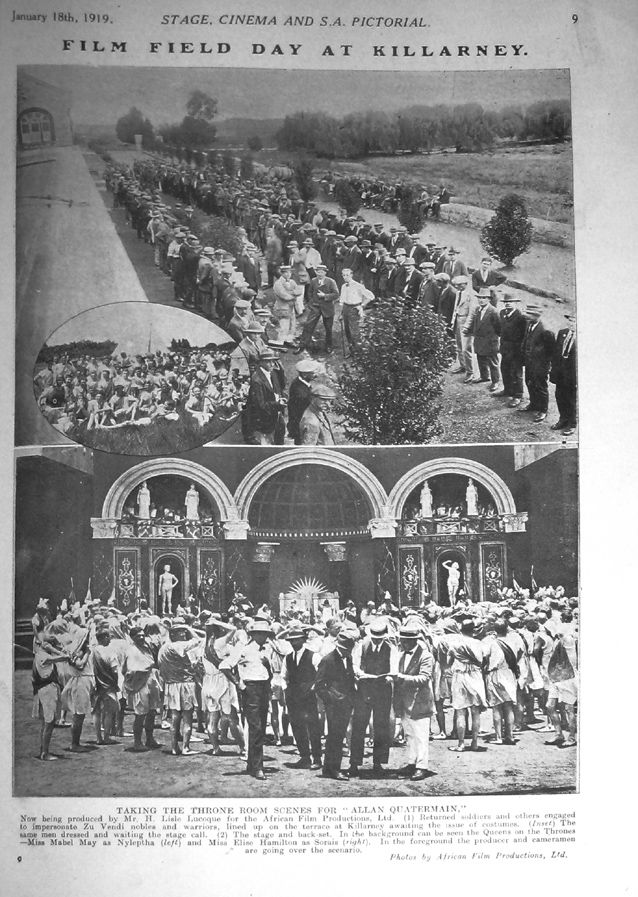

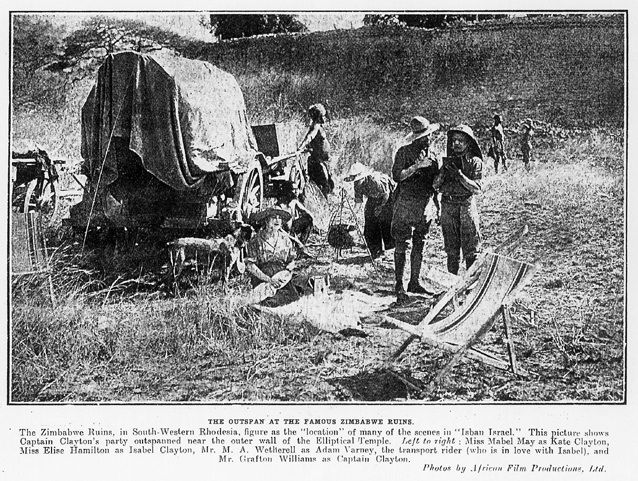

In subsequent AFP movies, however, black Africans progressively disappeared from view. We can contrast the photographic record of real black or Coloured actors appearing in AFP’s King Solomon’s Mines (1918) (Figs.3.11 and 3.12) with the subsequent production of Allan Quatermain (1919), which featured hundreds of white extras (Fig. 3.13) but apparently only two black actors. In the movie Isban Israel (dir. Joseph Albrecht 1919), which was filmed on location inside the ancient walls of Great Zimbabwe (Fig. 3.14), African actors were limited to a few guards standing still in striped bathing dresses (Stage, Cinema & S. A. Pictorial, 23 November 1918, 16-17, 18 January 1919, 9, 15, 15 March 1919 [supplement], 1, 22 November 1919, 1, 16-17).

Movies in South Africa, Edwin Hees has pointed out, “were a part of the developing discourse on segregation, however unconscious its makers may have been of this dimension of their film” (Hees 2003, 63)—a discourse that became heated public debate and electoral politics as the ranks of the urban unemployed were swelled by white servicemen returning from the war and “poor white” families being forced off the land. The Rose of Rhodesia cannot have played much part in that developing discourse because it was so little distributed in South Africa, while AFP productions were much more widely seen—particularly De Voortrekkers,which became an icon of emerging white Afrikaner nationalism and was reverentially shown across the country every December, long after AFP movie production had ceased in 1922-23. The Rose of Rhodesia, on the other hand, represented the beginnings of an alternative movie industry to the Schlesinger organization. Harold Shaw Film Productions might have better survived the undercutting of its finances by the postwar flood of Hollywood imports, by using its superior American movie-industry connections for co-productions, rather than tying itself to the British market, as AFP did, with movies based on H. Rider Haggard tales. Moreover, by basing himself on the periphery in Cape Town and taking “Rhodesia” as the subject of his first major independent movie, Harold Shaw showed that he had a regional Southern African perspective rather than a narrow South Africanism based on Johannesburg.

Illustrations

Fig. 3.1. Ralph Kimpton and Joseph Albrecht. Stage and Cinema, 7 April 1917, 6.

Fig. 3.2. Henry Howse and Norman H. Lee. Stage and Cinema, 1 September 1917, 19.

Fig. 3.3. Marmaduke Wetherell. Stage and Cinema, 27 May 1916, 2.

Fig. 3.4. Bawa Falls, Eastern Cape, South Africa, 2007. Photograph by Maryann Shaw.

Fig. 3.5. Colonel Johann William Colenbrander. Stage and Cinema, 4 August 1917, 6.

Fig. 3.6. African Films Trust advertisement. Stage and Cinema, 16 March 1918, 5.

Fig. 3.7. Dick Cruikshanks and The Zulutown Players. Stage and Cinema, 7 July 1917, 10.

Fig. 3.8. Unidentified actors in Zulutown Races. Stage and Cinema, 23 June 1917, front cover.

Fig. 3.9. Florence Creagh and unidentified actor in The Piccanin’s Christmas. Stage and Cinema, 16 October 1917, 12.

Fig. 3.10. Cast members of The Piccanin’s Christmas. Stage and Cinema, 16 October 1917, 13.

Fig. 3.11. Publicity still for King Solomon’s Mines. Stage, Cinema & S. A. Pictorial, 23 November 1918, 16.

Fig. 3.12. Publicity still for King Solomon’s Mines. Stage, Cinema & S. A. Pictorial, 16 November 1918, 17.

Fig. 3.13. Publicity still for Allan Quatermain. Stage, Cinema & S. A. Pictorial, 18 January 1919, 9.

Fig. 3.14. Shooting Isban Israel in Great Zimbabwe. Stage, Cinema & S. A. Pictorial, 22 November 1919, 16.

Works Cited

Ayliff, John, and Joseph Whiteside. 1962. History of the Abambos Generally Known as Fingos. Cape Town: Struik. First published in 1912.

The Bioscope (London).

Brooks, Bushnell, comp. 1993. Directors and Their Films: A Comprehensive Reference, 1895-1990. Jefferson: McFarland.

The Cape (Cape Town).

The Cape Argus (Cape Town).

The Cape Times (Cape Town).

Carter, Huntly. 1930. The New Spirit of the Cinema: An Analysis and Interpretation. London: Harold Shaylor.

Chaplin, Charles. 1963. My Auto-Biography. London: Bodley Head.

Darnton, John. Loch Ness: Truth is Stranger than Fiction. New York Times, 20 March 1994,www.nytimes.com/1994/03/20/weekinreview/loch-ness-fiction-is-stranger-than-truth.html (accessed 12 November 2007).

Davis, Peter. Against the Odds: In Search of a National Cinema in South Africa. H-Net book review of To Change Reels: Film and Culture in South Africa by Isabel Balseiro and Ntognela Masilela (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003), H-SAfrica@h-net.msu.edu (accessed 20 February 2004).

The Era (London).

“Ernest Palmer.” Entry on Internet Movie Data Base, www.imdb.com (accessed 27 February 2008).

Everson, William K. 1974. Berkeley Square(Fox, 1933). Directed by Frank Lloyd. New York: New School: WKE Notes, Film Series 20: Program #1 (11 June), www.nyu.edu/projects/wke/notes/newschool/ns_740611.htm(accessed 27 February 2008).

“God’s Soldier.” The Bioscope: Reporting on the World of Early and Silent Cinema,3 November 2007,http://bioscopic.wordpress.com/2007/11/03/ (accessed 10 August 2008).

Hammond, Margaret. 2004. Film Pioneer [Henry Howse]. The Salvationist (15 May): 10,www1.salvationarmy.org.uk (accessed 15 January 2009).

“Henry Howse.” Entry on Internet Movie Data Base, www.imdb.com (accessed 27 February 2008).

Holmes, Janet, and Miriam Meyerhoff. 2004. The Handbook of Language and Gender. Oxford: Blackwell.

The Kinematograph Weekly (London).

“Lorimer Johnston.” Entry on Internet Movie Data Base, www.imdb.com (accessed 12 February 2008).

The Los Angeles Times.

Low, Rachael. 1950. The History of the British Film 1914-1918. London: Allen & Unwin.

———. 1971. The History of the British Film 1918-1929. London: Allen & Unwin.

Lussier, Tim. “The Tragic Flugrath Sisters” (posted 1999),www.silentsaregolden.com/articles/flugratharticle.html (accessed 8 February 2008).

Macmillan, Hugh. 2005. An African Trading Empire: The Story of Susman Brothers and Wolfsohn, 1901-2005. London: I. B. Tauris.

“Marmaduke A. Wetherell.” Entries on www.imdb.com & www.citf.com (accessed 8 February 2008).

Mostert, Noël. 1992. Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa’s Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People. New York: Knopf.

The Rand Daily Mail (Johannesburg).

Rapp, Dean, and Charles W. Weber. 1989. British Film, Empire and Society in the Twenties: The “Livingstone” Film. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 9, no. 1: 3-17.

Reed, Douglas. 1950. Somewhere South of Suez, www.douglasreed.co.uk (accessed 20 January 2009).

Stage and Cinema (Johannesburg). Renamed Stage, Cinema and S.A. Pictorial in 1918.

Stotesbury, John A. 1993. A Critical Reassessment of Gender in John Buchan’s Prester John. Nordic Journal of African Studies 2, no. 1: 103–115.

Endnotes

[1] Howse is thought to have filmed many, if not all, of the early films of Booth that are featured on God’s Soldier, a DVD compilation of originals archived in the British Film Institute (see “God’s Soldier” 2007).

[2] “Mofti” sounds remarkably like moffie, now Afrikaans slang for “gay” but a word probably of more complex origin among Coloured people in the Western Cape (Holmes and Meyerhoff 2003, 406).

[3] “It took them between five and six weeks to do the journey” (The Bioscope, 25 September 1919, 21).

[4] Thanks to Vreni Hockenjos for pointing this out.

[5] Salvaged parts of The Symbol of Sacrifice are collected on a DVD titled Isandhlwana Zulu Battlefield available from Zulubattlefield Productions (Natal) at info@zuluwars.co.za.

[6] For a photo of “The ‘Zulutown’ Players: Dick Cruikshanks and his Company of Native Movie Stars”, see Stage and Cinema, 7 July 1917, 10.

Created on: Thursday, 23 July 2009