Abstract

The return of The Rose of Rhodesia to the public domain comes at a remarkable time for Zimbabwe. This melodramatic film about an “unusually large rose diamond” makes an uncanny prophesy about future black African leadership of the country. And yet, in an irony of history, Zimbabwe is currently undergoing possibly the worst political and humanitarian crisis in its history at the same time as it experiences a diamond boom following the discovery of deposits in Manicaland in the eastern highlands. The rediscovery of The Rose of Rhodesia at this convulsive moment, this paper argues, invites us to tease out the symbolic connections between the film and the current situation in the Zimbabwe mining sector, the role of the state in protecting national wealth, and the Mugabe regime and its treatment of citizens.

………

The restoration and circulation of the silent-era film The Rose of Rhodesia (1918) comes at a remarkable time for Zimbabwe, the country which bore the name Rhodesia for nearly ninety years.[1] This melodramatic story about the theft of an “unusually large rose diamond” (Intertitle 23) is interspersed with subplots of romantic love, a brewing African uprising against European imperialism, interracial friendship, and an uncanny prophesy about future black African leadership of the country. The film returns to the public domain as contemporary Zimbabwe goes through arguably the worst political and humanitarian crisis in its history. The legitimacy of the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF) government led by President Robert Mugabe, which has been in power since the end of colonial rule in 1980, is now being seriously contested, and in the general elections of 29 March 2008 the opposition party Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) won a parliamentary majority. Morgan Tsvangirai, the MDC’s presidential candidate, won 47% of the presidential votes against Mugabe’s 43%, but during a violent run-off Mugabe controversially “regained” power in alliance with army generals. Mugabe’s so-called re-election has been vigorously rejected by many, among them longstanding detractors such as the USA, Canada, Britain and the EU, Australia and several African countries. This debacle offers further evidence of Mugabe’s dictatorial rule, his intolerance, and his abuse of human rights, all of which have become particularly glaring in the wake of the violent takeover of white-owned farms since 2000.

In light of its myriad social, economic, political, and humanitarian problems, Zimbabwe has been touted in some quarters as a failed state, often mentioned in the same breath as disaster areas such as Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Sudan’s Darfur region. Mugabe and ZANU–PF, however, argue that they are being punished with sanctions and harsh criticism for redistributing formerly white-owned farms among black Zimbabweans, the historically marginalised majority who lost their land to colonial settlers. While steeped in all these problems, it is therefore ironic that Zimbabwe should be experiencing a diamond boom in the wake of the discovery of deposits in the rural Chiadzwa area under the control of Chief Marange in Manicaland in the eastern highlands. When precious minerals are discovered in a troubled country, as Alex Magaisa has noted, they can easily become a curse rather than a means of alleviating the suffering of its people (Magaisa 2008). The rediscovery of The Rose of Rhodesia at this convulsive moment in Zimbabwe’s history invites us to tease out the symbolic connections between the film and the current situation in the Zimbabwe mining sector, the role of the state in protecting national wealth, and the Mugabe regime and its treatment of citizens.

Hermeneutic and interpretive, my approach here will take as its starting point the view that there can be no objective positions in cinema since, in the words of Alain Badiou, film cannot be situated “in itself,” that is to say, film does not produce intelligibility on its own (Badiou 2005, 83). The film producer and the viewer both contribute to the singularity of the cinematographic experience, and as both are situated subjectively, the film’s intelligibility and sensibility depends on their situations. Methodology is crucial for analysing film because it provides critical tools or a set of procedural rules for engaging the filmic text, rules which contain within them assumptions about the nature of the object of study (Yearwood 2000, 13). In this essay, I will draw on Jay Ruby’s notion of reflexivity (Ruby 2000) as the process of disclosure of film producers’ biases and ideological leanings, in order to evaluate the film’s ideological tendencies in relation to the racial and class identity of its director and producer Harold Shaw. Shaw’s shaping influence is apparent in the ideological assumptions and tone of The Rose of Rhodesia, which endorses and legitimises a paternalistic system of colonial rule. In presenting an interpretation of the film against the backdrop of colonial and postcolonial Zimbabwean realities, I offer a critique of state repression as a means of asserting direct control over diamond deposits.

This essay offers an intertextual reading of the film in light of selected recent articles on contemporary Zimbabwe. The latter, which have been published in the popular press in the wake of activities in the diamond fields of Chiadzwa in the eastern highlands of Zimbabwe, represent a diverse range of political opinions: Chenjerai Hove, an award-winning exiled Zimbabwean fiction writer and social critic; Alex Magaisa, a lawyer and political analyst; Nathaniel Manheru, a pro-government weekly columnist for the state-owned Heraldnewspaper; and Masola wa Dabudabu, one of Manheru’s critics. All writers are Zimbabweans and three of them part of the diaspora. Manheru is suspected to be the pen name of George Charamba, the Permanent Secretary of Information and Publicity in the Office of President Mugabe. Journalist Masola wa Dabudabu recently remarked, “I wonder if I would not be far off the mark if I declared that Manheru is definitely a man with links in the rotten offices of the executive?” (wa Dabudabu 2008); and another Zimbabwean press colleague, Jeoffrey Nyarota, insists on using “Manheru” and “Charamba” interchangeably (Nyarota 2009, ).

My analysis will devote special attention to the leitmotifs and imagery constructed around real and imaginary diamonds and roses in both the film and these journalistic texts (Andrew 1976, 219). I will critique the film’s thematic concerns, its notions of regime legitimacy and human rights, and what might be called its prophetic statements, rather than technical aspects of cinematography. This is not to deny the latter’s impressive character: an array of camera angles is used to great effect, especially the wide angle shot that reveals scenery and characters while advancing the dramatic action; the stunt of Ushakapilla’s son, Prince Mofti, falling to his death from a sharp cliff, requires ingenious camera positioning and clever editing; and in Ushakapilla’s dream sequence, dissolving images of lithe bodies intermingling effectively simulate the haziness of real dreams. The human body as a site of meanings, costumes and props carry ethnographic significance that require separate critical consideration. The same applies to interracial relations as signified by a range of visual modes and their implications for equality, “tradition” and “modernity”. The Rose of Rhodesia is comprised of a melange of moving images and printed texts incorporated into the filmic narrative, including authorial intertitles, a newspaper story announcing the theft of the diamond and the reward offer for its recovery, and excerpts of a romantic novel which the heroine Rose Randall is reading.

The Rose of Rhodesia and colonial history

Although a work of fiction, The Rose of Rhodesia is best understood against the backdrop of colonial history. The film has a number of direct historical and political resonances. Firstly, the “Rhodesia” in the title invokes the territory that now forms Zimbabwe. Chief Ushakapilla’s name resonates strongly with that of the legendary founder of the Zulu nation, King Shaka, whose military excesses caused his army general, Mzilikazi of the Khumalo clan, to flee and, ultimately, settle in the southern part of present-day Zimbabwe. Upon Mzilikazi’s death, he was succeeded by his son Lobengula, the last Ndebele King, who was defeated by the British in the Anglo-Ndebele War of 1893 and fled Matabeleland to an unknown fate. Ushakapilla can be seen as an imagined descendant of the Khumalo, who have a link with the Zulu.

Lobengula and the Ndebele Kingdom were casualties of the British colonial enterprise. On 30 October 1889, Cecil John Rhodes’s agent Charles Rudd persuaded Lobengula to grant a monopoly of all minerals both in his kingdom and to the north, in Mashonaland. Rhodes, who owned the De Beers diamond monopoly and the Consolidated Gold Fields of the Rand, anticipated larger mineral deposits in the lands north of the Limpopo. After securing the Rudd Concession, he thus immediately sought British imperial protection for his mineral speculations. Without such protection, the Rudd concession was vulnerable to Afrikaner and Portuguese encroachments and to Lobengula’s revoking of the treaty. An extension of empire was needed in order to secure these claims and thereby seal Rhodes’s monopoly (Robinson et al. 1981, 234).

Colonial anxieties about armed black African rebellion—anxieties upon which the dramatic tension of The Rose of Rhodesia is partly premised—were not without basis. The conflicts and costs associated with the colonisation of the Cape and Natal in South Africa were never far from the minds of colonial administrators. Even before the annexation of Matabeleland, the prospect of direct military confrontation with Lobengula and his impis evoked memories of earlier Anglo-Zulu clashes. By granting a charter to Rhodes’s British South Africa Company (BSAC), Colonial Secretary Lord Knutsford sought to avoid direct responsibility for the military and administrative costs of Britain’s newest southern African frontier (Robinson et al. 1981, 238). The Company bore the costs of the 1893 Anglo-Ndebele war which deposed Lobengula, and of the suppression of the joint Shona-Ndebele uprising of 1896-97, known popularly as the First Chimurenga. (The BSAC was to rule the combined territories of Mashonaland and Matabeleland for thirty years until the introduction of so-called Responsible Government in 1923.) The Rose of Rhodesia’s narrative and the figure of Chief Ushakapilla make most historical sense, in other words, when viewed as representative of the period immediately following the First Chimurenga.

Ambition, prophecy and vision

The Rose of Rhodesia’s tone is highly colonial. The white missionary James Morel is Ushakapilla’s trusted adviser, a relationship mirroring that between King Lobengula and the missionary Robert Moffat. Though close to Lobengula, Moffat was a double-dealer who induced the king to sign the fraudulent Rudd Concession ceding mineral rights to the BSA Company (Samkange 1968).

In the film, the white governor practises benevolent colonialism, handing over tracts of land at his convenience. After Ushakapilla’s only son, Prince Mofti, dies in a hunting accident, the chief abandons his plot to launch a rebellion and, with it, a vision of his son as crowned king of Africa.[2] Morel’s earlier exhortations against Ushakapilla’s impatience suddenly acquire a morbid note: rebellion is sinful. Looking back, Ushakapilla sees Mofti’s death as divine punishment for his own audacity and ambition. Heart-broken, he throws the hoard of treasure, which he planned to use to pay for his war, from the traditional rock of sacrifice into the river. There is no one to succeed him, rendering his vision futile. Ironically, Mofti did not sympathise with his father’s ambitions. Mofti’s sense of multi-racialism was not radical enough to extend to wresting land from the colonial authorities. He is “acculturated,” that is to say, he has adopted traits and sensibilities from Christianity and European culture in a way that reminds students of history how the BSAC sent Lobengula’s children to schools in South Africa in order to defuse any attempt at restoring the Ndebele empire (Samkange 1968). When Ushakapilla gives up his grand ambition, the film producer’s ideological voice intrudes into the narrative in the form of a prophetic intertitle: “Here endeth the reign of the black Chief, until time make him white and he prove himself worthy to rule this country as the great white Chief does” (Intertitle 119).

The patronising tone of the colonizer is unmistakeable: whiteness here signifies civilisation and social justice. The Governor’s decision to give tracts of land to Ushakapilla is intended to suggest the fundamental reasonableness of the colonial system. Historically, however, the colonial land redistribution system was skewed in favour of white immigrants and blacks were forcibly displaced from areas designated “white” (Riddell 1978). The Rose of Rhodesia anticipates black rule in the remote future, preferring a black leadership that emulates the best values of its white predecessors. Despite acknowledging isolated instances of white misbehaviour by individual misfits, such as the thief Fred Winters and the drunks in the pub, the film’s assumption of white supremacy confirms its inability to conceive of cultural parity in any form.

Roses and diamonds as symbols

The symbolism of roses and diamonds runs throughout both the film and contemporary Zimbabwean journalistic texts. The rose icon represents Rose Randall as well as the memory of her mother, and it is also planted on Mofti’s grave—the young man whose sensibilities had been “purified” by Christianity. The rose and diamond are metaphors for virtuous womanhood and treasured nationhood. The film’s iconic diamond is owned by the Karoo Diamond Mines Syndicate, whose ownership it presents as axiomatic—a reflection of the political legitimacy of private companies in colonial-era Africa and the “spoils of conquest” ideology which has left its traces on this early feature film. (Indeed, it is not far-fetched to draw a parallel between the Karoo Syndicate and De Beers or the BSAC’s own mining companies.) In the story, the rose-coloured diamond is stolen from the syndicate’s directors by Fred Winters, a white overseer. Investigations implicate Winters in the theft but he escapes. The Karoo Syndicate immediately places an advertisement in the newspaper offering a reward of £5000 for the recovery of the precious stone. Meanwhile, Winters wanders in the Karoo desert where he collapses senseless from thirst and exhaustion. Namba, a native under Chief Ushakapilla, finds him and steals the diamond and other valuables, yet at the same time showing his victim human compassion by giving him water before disappearing into the wilderness. Namba hands the diamond to Ushakapilla in obedience to the latter’s instructions to “work in the white man’s diamond mines” (Intertitle 20) and bring back diamonds and gold to buy arms for an uprising against white rule. Possession of diamonds, the film suggests, brings with it control over integral aspects of political and cultural life.

The young white heroine embodies the rose motif in her very name, even as the image of Rhodesia as a tender rose is dramatised in Rose’s character and actions. The daughter of a poor gold-prospector named Bob Randall, she is the shining beauty in the wilderness, entertaining herself by reading literary romances in a dreary environment. Her life is imaginatively interwoven with the narrative developments of the story she is reading. Sexual abstinence by youths is here considered virtuous, as in nearly all cultures throughout the ages, especially for single women; Rose resists Fred Winters’ attempts at seduction. These lofty standards of chastity are obliquely reiterated to Rose through the story of Lord Cholmondeley and Betty Beetle in an excerpt of the romance story she is reading. Act Three of the film manipulates the stylistic technique of story-within-a-story in order to denounce the seduction of youth. Rose’s literary doppelganger is less shrewd: “Betty Beetle was only too willing to please the lord [Cholmondeley],and, in so doing, she spoiled her chances of ever becoming …[his wife]” (Intertitle 81); “The very same night, the noble Lord left the village, and she never saw him again” (Intertitle 82). For heeding this morally conventional message, Rose is rewarded by becoming the wife of a missionary’s son. The Karoo Syndicate grants her a handsome reward of £10,000 reward for returning the diamond, which Ushakapilla had given her as gesture of thanks for planting a rose on his son’s grave, and the film’s final scene presents Jack and Rose living a comfortable life with their large family (Fig. 9.1).

The only other image of womanhood in the film is the barmaid who is almost sexually assaulted by drunkards. Ironically, given his identity as a potential corrupter of youth, Fred Winters is here the defender of female virtue. Even so, the barmaid’s presence in a place of drunken male debauchery implies that she is not a woman of virtue. She stands, in effect, as a moral counterpoint to the angelic Rose. The barmaid evokes the image of what James Baldwin (Baldwin 1994, 2618), articulating the dominant social prejudices of his day, once disconcertingly described as the “semi-whore” who voluntarily moves in male territory.

The diamond leitmotif also ties The Rose of Rhodesia to postcolonial Zimbabwe, where it continues to be used as a signifier of women and gemstones in unexpected ways. Reporting on the country’s newest craze for minerals, Zimbabwean author Chenjerai Hove likens the diamonds found in the Chiadzwa district to women. Of a visit made years earlier with the purpose of helping to negotiate a marriage contract, he recalls: “My brother’s other son had met and fallen in love with a woman from Chiadzwa…. Yes, another type of diamond…. Now, in Chiadzwa, they have found a new type of diamond, not the one we went to fetch. This time it is real diamond….” (Hove 2007). Yet this “real diamond” is a force of destruction, “cling[ing] to lovers’ fingers like a shiny little devil, and sometimes creat[ing] gruesome casualties”. Writing the following year about state excesses in Chiadzwa, Magaisa concurs: “the beauty of the stone … [seems] like a curse” (Magaisa 2008).

Press reporting in Zimbabwe often conflates real women with geographic terrain and precious stones, with the one being magically transformed into the other. The arrival of illegal miners evokes narratives of invasion, loss of innocence, defilement and ravaged womanhood, many of them with an implied sexual subtext. Thus Magaisa records how “the girls and women of Marange [are] violated and raped in the lawless climate,” victims of a diamond rush in which “this stone has taken a more sinister meaning that far outweighs the apparent signification of wealth” (Magaisa 2008). Even more gruesome is the description by the government’s own apologist Nathaniel Manheru:

[T]he raping of Chiadzwa extended beyond its once-virtuous women; it reached its once-peaceful earth which got turned upside down, all to appease vapid greed. Today Chiadzwa lies prostrate, badly wounded, copiously bleeding from countless assaults. Who will suture it? Who will bandage its suppurating wounds? Above all, who shall repair her collapsed morality, treat her cankered lungs? (Manheru 2008, italics in original)

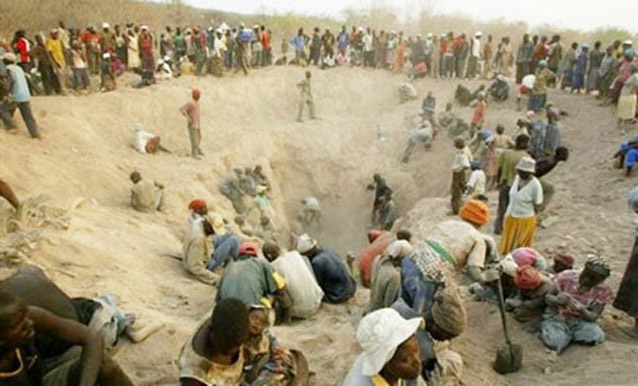

The frenzy which accompanied Kimberley’s “Big Hole” mine in the late nineteenth century, when the discovery of diamonds in South Africa prompted a rush of fortune-seekers, makes a historic return in both the film and the press images of Chiadzwa (Fig. 9.2). Although Randall is first pictured leaving the diggings with an African employee (Fig. 9.3), he and Winters are subsequently presented as working the mine on their own without black native labour (Fig. 9.4), a prospect that seems fantastic in light of what is now known of colonial labour relations.

Authorial voices dominate in the reporting on Chiadzwa. Local people are romanticised but denied self-expression, except in one instance in which a local informant tells Hove that the Zezuru ethnic group is exploiting diamonds at the expense of locals; ordinary Chiadzwa people are otherwise spoken about or for. When they act, they are misguided in giving hospitality to the invaders and further the rape of the environment. The Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci argues that although one can speak of intellectuals, one cannot speak of non-intellectuals because the latter do not exist (Gramsci 1971, 321). For him, there is no human activity from which every form of intellectual participation can be excluded. By denying any semblance of intellectual ability in ordinary people, certain dominant minority voices generalize their own opinions and values to everyone, and claim to speak for the common good, while high-flown rhetoric about patriotism and protecting national sovereignty is deployed to class-specific and individualistic ends, the defence of trade monopolies, and political power (see Minh-Ha 2005, 263).

The motifs of environmental degradation, disruption, and corrupted innocence are repeatedly romanticised in these accounts. Manheru evokes an image of ecclesiastical purity when he recalls the African Pentecostal sect popularly known as Mapositori ekwa Marange, which has its traditional base in the Chiadzwa area. Sect members wear “sinless white” gowns that signify purity and rustic piety (Manheru 2008). Somewhat hyperbolically, Manheru claims that the discovery of diamonds “shattered in an instant” Chiadzwa’s “peace of generations”. Such glorification of the past as an imaginary time of innocence conveniently glosses over the region’s violent pre- and post-independence history: Manicaland was the scene of intense fighting during Zimbabwe’s liberation war or Second Chimurenga in the 1970s, and RENAMO rebels from neighbouring Mozambique, originally backed by the Rhodesian authorities, destabilised the region during the post-independent period in order to wreck the alliance between ZANU–PF and Mozambique’s ruling FRELIMO government. For Manheru, women are enchanting symbols of innocence, unscrupulously exploited by rapacious predators. Strangers with questionable integrity come as suitors to Chiadzwa, corrupting its yielding maidens and environment, both somehow paradoxically complicit in their exploitation insofar as they readily give shelter, food, and sexual gratification. For those who share Manheru’s perspective, this requires a lofty protector of virtues and morals—none other than the people’s central government and its gallant military!

But government protection brings dire consequences. Thus Magaisa laments: “For the villagers who have been displaced; made strangers in their own homes, the beauty of the stone would seem like a curse” (Magaisa 2008). Zimbabwean peasants do not have rights over supposedly communal land that in fact belongs formally to the state, which can move people arbitrarily. According to an informant who worked for African Consolidated Resources (ACR), the company which held the legal mining rights before the chaotic rush, agitators from the ruling ZANU–PF party had incited local people to invade the deposits at Chiadzwa and dismiss the legally registered company as “foreigners”.[3] In the ensuing mayhem, the government evicted ACR’s personnel and used excessive force to seize control of the fields.

Diamonds as a site of contestation

Several reports attest to the presence of a range of nationalities converging on the rustic and underdeveloped Chiadzwa district prior to the military’s intervention. The so-called “diamond gladiators” mentioned in Hove and Manheru’s articles include Israelis, Lebanese, Belgians, Afrikaners (South Africans), Japanese, Indians, Sierra Leoneans, Liberians, Mozambicans, Angolans, Americans, and Germans as well as Zimbabwean political heavyweights and businessmen. In an unfortunate witticism, Hove mischievously conflates all these various fortune-seekers with the Zezuru, who thereby suddenly become the single most pernicious presence. Since Mugabe himself belongs to the Zezuru sub-group of the dominant Shona ethnic group, critics need to avoid making the simplistic argument that it is Zezuru hegemony and cronyism which has reduced Zimbabwe to its current pathetic state.

Although Manheru strategically excludes the Zimbabwean presence from his description of the looting, he refers acidly to this multi-ethnic and multiracial “human miscellany” as “a mini United Nations in sin and greed”, and brazenly celebrates their capture and torture by the Zimbabwean army. (Another writer, Masola wa Dabudabu has called Manheru an inhuman sadist and equated military actions with “state terrorism”.) He pretends that the destabilisation of innocence and lawful existence warrant brutal state intervention and “a shock therapy” which disregards international conventions on the proper treatment of prisoners. Bragging about how the government has reasserted its authority “in this wild, wild East” where “untouchables” are either “slaving, wounded or dead,” Manheru recounts how prisoners are forced to refill gullies “in record time” using their bare hands and their “fingers are sore and finishing (sic)”. With diabolical relish, Manheru declares: “It is painful payback time… Chiadzwa, once a place for dashing fortune-seekers, has become Chiadzwa the place of unrelieved pain”.

Lost innocence in Manheru’s account is counterposed to an untenable image of a lawless wilderness, a Wild West needing to be wrested from the control of unscrupulous treasure hunters. The army’s heavy-handedness is justified in terms of dangerous circumstances in which daredevil treasure hunters have prepared themselves for pitched battles. Such drastic responses to “lawlessness” instantly caused an international outcry from human rights groups and opponents of the Mugabe regime, who view the Chiadzwa debacle as further testimony of the regime’s repressiveness. In light of the extra-judiciary killings perpetrated by government forces in their seizure of the Chiadzwa fields, calls have been made for the United Nation’s Kimberley Process Certification Scheme—which enables buyers to determine whether rough diamonds have originated in a conflict zone—to suspend Zimbabwe.[4] Other critics see the diamonds as providing a financial lifeline to a rogue regime.

In turn, Mugabe’s government has countered by claiming to be the legitimate arm of the law, denouncing all those who criticize its actions as advocates of a “regime change” agenda prompted by pique at the land reform programme. Hence Manheru warns of the selfish motives behind the American and British interests in the Chiadzwa diamonds fields: “Whichever way, the uninvited patrons of Chiadzwa will not come back. And the prophet shall descend on this land, happy and fulfilled once more”. The “prophet” in question is a composite figure of pan-Africanist ideology, as articulated by the likes of Kwame Nkrumah, Amilcar Cabral, Samora Machel, or perhaps even Mugabe himself, who claims that he is seeking to continue the original pan-African ideals of political and economic independence (Mugabe 2007, 1-11). In using the discourse of counter-imperialism, the regime’s stalwarts are laying claim to a kind of righteousness by which the butchering of illegal miners and traders in Chiadzwa can be justified on the grounds of protecting national wealth from greedy “foreigners” and their local cohorts.

Manheru’s articles are generally regarded as ZANU–PF’s moral and intellectual barometer; by reading him one can accurately gauge the regime’s thinking and strategies. The regime is motivated by what might be called a “transcendental” ideology of patriotism. Their actions are exalted, extraordinary, and possessed of a higher wisdom and morality that justify harmful behaviour in the name of a higher good, ostensibly the protection of the nation’s wealth and integrity for the benefit of the majority. Any criticism of its excesses is regarded as the work of Western “imperialists” and their local agents. Loyalty to binding ideological concepts, such as “the revolutionary struggle,” “nationalism,” or “Chimurenga,” provides justification for temporary or permanent breach of human rights (Cohen 1996, 530).

To be sure, Mugabe defies the prophetic descriptions of The Rose of Rhodesia as regards the calibre of future black leaders of “Rhodesia”. Rather, he can be seen as the reincarnation of an unrepentant Ushakapilla, a modern version of Shaka Zulu fraught with the contradictions of nation-building and respect for human rights. To judge from the protective stance adopted with regard to crisis in Zimbabwe by regional bodies such as the Southern African Development Community and the African Union, Mugabe’s way of thinking might be said to “rule” Africa insofar as he is still able to count on many sympathisers in these organizations. The “prophet(ess)” of Zimbabwean revolutionary tradition is Mbuya Nehanda, the martyr of the First Chimurenga hanged by the British for her central role in the insurrection, who predicted in her final words that her bones would be “resurrected” (see Pongweni 1981; Hove 1988; Samupindi 1990). Mugabe may well be Nehanda’s grisly postmodern reincarnation.

Mugabeism and the strongman prophecy

It has been argued that politics and the state in Africa operate through favouritism, personal rule, and patrimonialism because its social classes are not yet sufficiently developed to play their decisive roles (Kaarsholm 2006, 3). Personal rule in the form of Mugabeism has predominated in Zimbabwe since 1980, with systematic vilification, ridicule, and even direct physical attacks on individual political rivals, especially those from the opposition parties.[5] Patronage and cronyism are deeply entrenched, with wealth-distributive alliances coalescing around the figure of the President. As the MDC’s political influence has grown since 2000, Mugabe has systematically forged alliances with the War Veterans and the top echelons of the military in order to ensure state and government control. Through systematic patronage, top army officials now head major quasi-state ventures, including the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission. Top military personnel, either retired or still serving, are ubiquitous in state projects. The intellectuals and media figures who prosper are those who lend their vocal support for the status quo. The “prophecy” implied by Manheru entails a new redistributive system which benefits a select group of people who are paid and fed to defend the regime at any cost. The result is an extreme system of what has been called “necropolitical” governance or “the subjugation of life to the power of affluent death” (Mbembe 2003, 39; see also Kaarsholm 2006, 5). This explains the brazen readiness to kill or abduct political oppositions or any threats to national wealth. In Mugabe, the stereotype of post-colonial African politics as conspicuous consumption by gluttonous leaders of government has become a reality (see Mbembe 2001).

The failure of electoral democracy in Zimbabwe signals a power struggle whose main determinants are no longer the citizens or voters but the coercive instruments of the state and those who control them, even as the Mugabe regime continues to wage a propaganda war to legitimise its system (Mhiripiri 2008). Elections have been rendered absurd by Mugabe and his military allies, who announce in thinly veiled terms on state media, often just before a key presidential election in which Mugabe is facing stiff competition, that they will refuse to salute a leader without “war credentials”—declarations that would be treasonous in any self-respecting constitutional democracy—should the electorate vote “unfavourably”. It follows that the military should be heavily involved in the Chiadzwa diamond fields. Indeed, a crack-squad using helicopters equipped with automatic rifles is the latest feature of Zimbabwe’s first high-tech war over diamonds (see Swain 2008; Manheru 2008; wa Dabudabu 2008; Fenandes 2008).

The contrast between The Rose of Rhodesia and the Zimbabwean government’s actions in Chiadzwa is especially remarkable given the way in which the detective Brown effects a civilian arrest on Winters with the application of minimum force. The oral and written stories from Chiadzwa, by contrast, offer shocking allegations of massacres. Again and again, the police and soldiers sent to guard the deposits themselves end up digging, or receiving bribes even after major clamp-downs on illegal miners and traders. In his critical analysis of events in the “cursed’ fields, where state-instituted lawlessness now reigns, Magaisa sees an oblique replay of the chaotic and ill-fated land reform campaign. As he observes bluntly:

The government spilt the milk a few years ago when it allowed lawlessness to decide the land reform exercise. Then we had the new breed of “New Farmers”. Today, the same lawlessness defines the activities in Marange. We have a new breed of “New Miners”. It is just a continuation of the same old and tragic theme. Not even the locals of Marange who should benefit most are getting just rewards. Instead, they have been displaced and used. The company that owns legal title to the claims, African Consolidated Resources plc, founded in Zimbabwe and listed on the London Stock Exchange, was reportedly evicted unlawfully from Marange—this is a country which hopes to attract foreign investment; a country where property rights are decided by the fist, not by the law (Magaisa 2008)[6]

Magaisa succinctly captures the human tragedy associated with diamonds, which he evokes by reference to the 2006 movie Blood Diamond about the violent trade in African diamonds. Instead of improving the quality of Africans’ lives, he notes with regret, gems and precious metals, with the exception of South Africa and Botswana, have brought civil war and anarchy. The gruesome fictional events of Blood Diamond (dir. Edward Zwick, 2006) mirror the increasingly unstable situation on the ground in Chiadzwa. As Magaisa speculates: “The beautiful stone of Marange could well become the ugliest curse on the nation…. The beautiful stone of Marange could easily become a catalyst for implosion” (Magaisa 2008).

Conclusion

This essay does not claim to have given expression to the majoritarian and subaltern voices caught up in the Chiadzwa debacle: they have yet to tell their stories. To use Gramscian terminology, no “organic intellectuals” from the fields of Chiadzwa have so far documented their experiences and concerns. However, it is possible that radical intellectuals and activists in the mould of Nigeria’s Ken Saro Wiwa, with a training in economics and environmental law, will emerge to defend the interests of their ethnic group against a grasping and demoralizing state authority. At such a time, The Rose of Rhodesia offers itself as a fresh discursive site to examine issues of political legitimacy, sovereignty, and human rights in Zimbabwe. Indeed, the film’s thematizing of diamonds presents an uncanny parallel with the sudden availability of diamonds in a country that is currently in its darkest hour and whose leadership has resorted to the use of excessive force in what Achille Mbembe calls the “systematic application of pain” (Mbembe 2001, 103). It constitutes an imaginative space for rethinking (post)colonial history, the use of violence in forging national consciousness and narratives of legitimacy, and the shaping influence of material resources on contested historical memories. At a time when critics are asking whether the majority of Zimbabweans (including those displaced from Chiadzwa diamond fields) are citizens or subjects (Mamdami 1996), and as the ZANU–PF regime becomes increasingly reliant on the army and extrajudicial measures of control, The Rose of Rhodesia enables us to examine the range of moral arguments and tactics—including repression, collusion, and insurrection—elicited by struggles over state power in the postcolony.[7]

Illustrations

Fig 9.2. Open mining at Chiadzwa, 2008. Photograph by kind permission of Chenjerai Hove.

Works Cited

Andrew, J. Dudley. 1976. The Major Film Theories. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Badiou, A. 2005. “Philosophy and cinema.” In Infinite Thought, 83-94. London: Continuum.

Baldwin, James. 1994. “Sonny’s Blues.” In The Heath Anthology of American Literature, Volume 2, ed. Paul Lauter, 2615-35. Toronto: Heath. First published in 1957.

Cohen, S. 1996. “Government Responses to Human Rights Reports: Claims, Denials, and Counterclaims.”Human Rights Quarterly 18, no. 3: 517–43.

Fenandes, J. “Bodies Pile Up at Mortuary as Soldiers Diamond Operation Continues.” Zimbabwe Journalists, http://www.zimbabwejournalists.com/story.php?art_id=4997&cat=1 (accessed 19 December 2008).

Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Selections From the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Hove, Chenjerai. 1988. Bones. Harare: Baobab Books.

———. “The Many Diamonds of Chiadzwa.” Zimbabwe Journalists, http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/mines44.19067.html (accessed 19 December 2008).

Kaarsholm, Preben. 2006. “States of Failure, Societies in Collapse? Understandings of Violent Conflict in Africa.” In Violence, Political Culture and Development in Africa, ed. Preben Kaarsholm, 1-24. Oxford: James Currey.

Magaisa, A. “Marange’s Silent War of Stones.” New Zimbabwe, http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/magaisa103.18993.html (accessed 18 December 2008).

Mamdani, M. 1996. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Kampala: Fountain.

Manheru, N. “Reasserting Authority in the Wild, Wild East.” New Zimbabwe, http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/mines43.19060.html (accessed 19 December 2008).

Mbembe, Achille. 2001. On the Post-Colony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———. 2003. “Necropolis.” Public Culture 15, no. 1: 11-40.

Mhiripiri, Nhamo. 2008. “Zimbabwe Government’s Responses to Criticism of Operation Murambatsvina/Operation Restore Order.” In The Hidden Dimensions of Operation Murambatsvina in Zimbabwe, ed. Maurice Vambe, 149-58. Harare: Weaver.

Minh-Ha, Trinh T. 2005. “All-Owning Spectatorship.” In Theory in Contemporary Art Since 1985, ed. Zoya Kocur and Simon Leung, 259-75. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Mugabe, Robert. 2007. “Our Cause is Africa’s Cause (interview with B. Ankomah).” New African (Summer): 1-11.

Nyarota, G. “The Enduring Reach of Willowgate.” The Zimbabwe Times, http://www.thezimbabwetimes.com/?p=10414#more-10414 (accessed January 25, 2009).

Pongweni, A. 1981. The Songs That Won the Liberation War. Harare: College Press.

Riddell, R. 1978. The Land Problem in Rhodesia. Gwelo: Mambo Press.

Robinson R., and J. Gallagher with A. Denny. 1981. Africa and the Victorians. Oxford: Macmillan.

Ruby, J. 2000. Picturing Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Samkange, S. 1968 The Origins of Rhodesia. London: Heinemann.

Samupindi, C. 1990. Death Throes: The Trial of Mbuya Nehanda. Gweru: Mambo Press.

Swain, J. “Battle For Zimbabwe’s Blood Diamonds.” Zimbabwe Situation,http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/dec7a_2008.html#Z5 (accessed 19 December, 2008).

wa Dabudabu, M. “The Sadist, Nathaniel Manheru,” New Zimbabwe Blogs, http://www.newzimbabwe.com/blog/?p=141 (accessed 19 December, 2008).

Yearwood, G. L. 2000. Black Film as a Signifying Practice. Trenton: Africa World Press.

Endnotes

[1] While I will here use the name Rhodesia to refer to what is now Zimbabwe, it should be noted until Zambia became independent in 1964 it was called Northern Rhodesia. Zimbabwe has been called Southern Rhodesia, was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and was simply Rhodesia (1961-1978), and Zimbabwe-Rhodesia (1978-1979), becoming just Zimbabwe in 1980. Some ex-Rhodesians nostalgically call the country Rhodesia to this day.

[2] The goal of a pan-African government is not far-fetched, as evidenced in early 2009 by the proposal for a United States of Africa made by Muammar Al Qaddafi, newly installed President of the African Union.

[3] ACR informant, interviewed by Nhamo Mhiripiri in Gweru on 31 January 2008. Informant requested to remain anonymous.

[4] Partnership Africa Canada document, entitled “No. 19649: Conflict Diamond Scheme Must Suspend Zimbabwe,” emailed to Nhamo Mhiripiri from the Africa InforServ address inforserv@africafiles.org on 15 December 2008.

[5] Bishop Abel Muzorewa, Joshua Nkomo, Edgar Tekere, Enoch Dumbutschena and, latterly, Morgan Tsvangirai have all offered credible challenges to Mugabe’s position and, in consequence, been subjected to various forms of intimidation, physical and verbal attacks, incarceration, and trumped-up charges of treason or conspiracy to assassinate.

[6] Paradoxically symbolizing popular power and violence, the fist is also a trademark gesture of Mugabe and ZANU–PF.

[7] This entire article was written before the formation of the Government of National Unity that includes both MDC and ZANU–PF politicians. The new inclusive government is clamouring for credibility and the Chiadzwa diamond fields remain a site for the attestation of good governance, political and economic accountability and transparency.

Created on: Wednesday, 12 August 2009