Compiled with the generous assistance of Neil Parsons and James Burns.

Fig. C1. Ink sketch of Harold Shaw, The Bioscope (London), 24 February, 1916, 759.

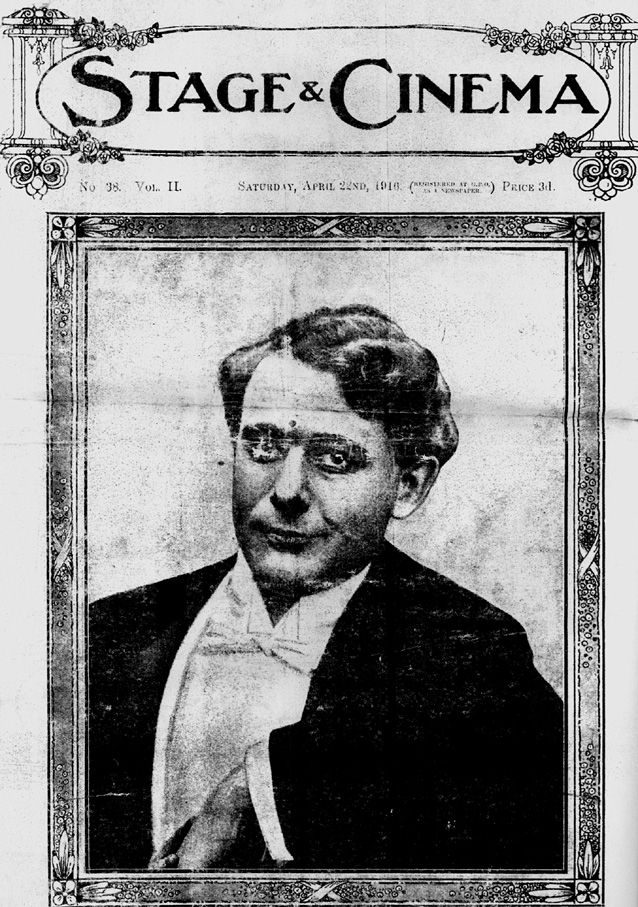

Fig. C2. Harold Shaw on the cover of Stage and Cinema (Johannesburg), 22 April 1916.

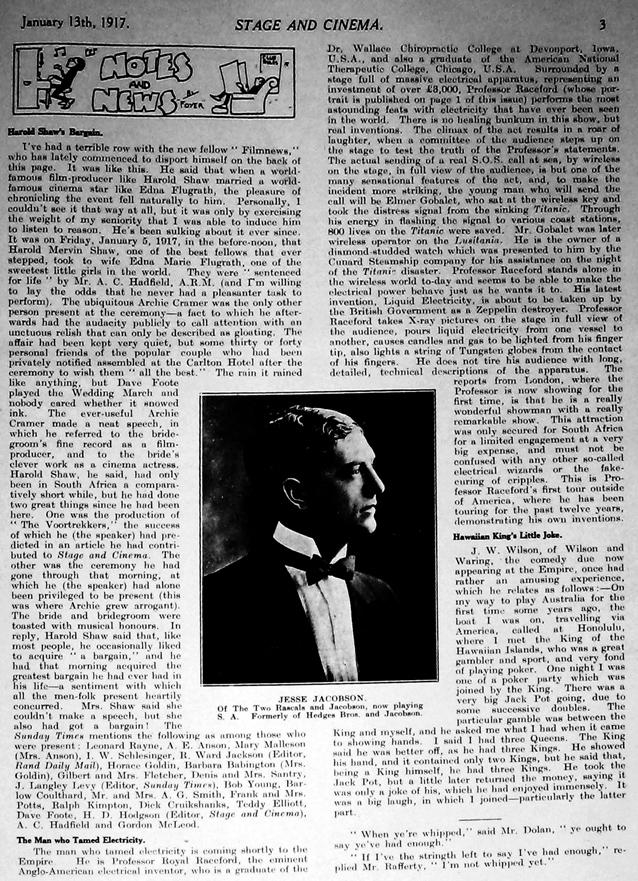

Fig. C3. “Harold Shaw’s Bargain”, Stage and Cinema (Johannesburg), 13 January 1917, 3.

Fig. C4. Henry Howse, “Adventures of a ‘Movie’ Man”, Stage and Cinema (Johannesburg), 24 February 1917, 2.

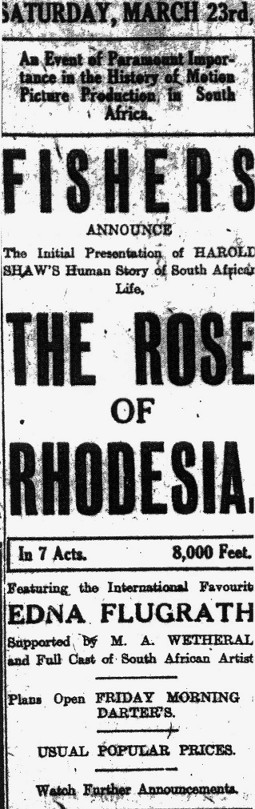

Fig. C5. The Cape Times (Cape Town), 17 March 1918, 9.

Fig. C6. The Rand Daily Mail (?) (Johannesburg), 27 April 1918, n.p.

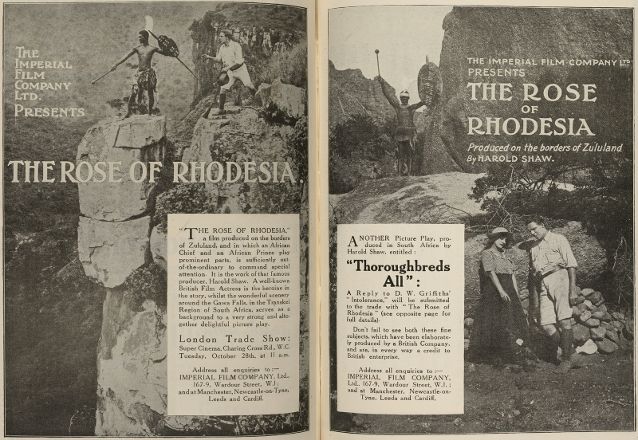

Fig. C7. The Rand Daily Mail (Johannesburg) 30 April 1918, 8.

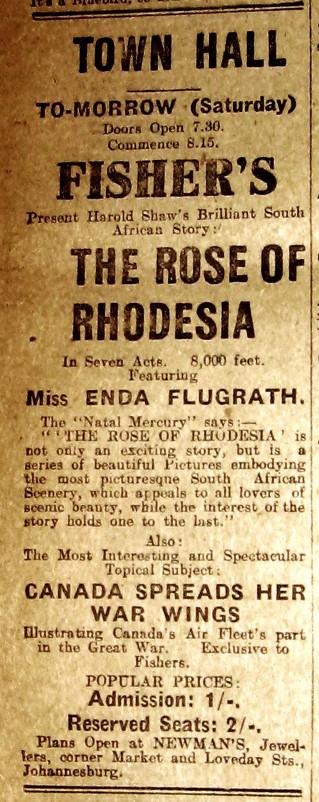

Fig. C8. “African Prince as Film Star”, The Bioscope (London), 25 September 1919, 21.

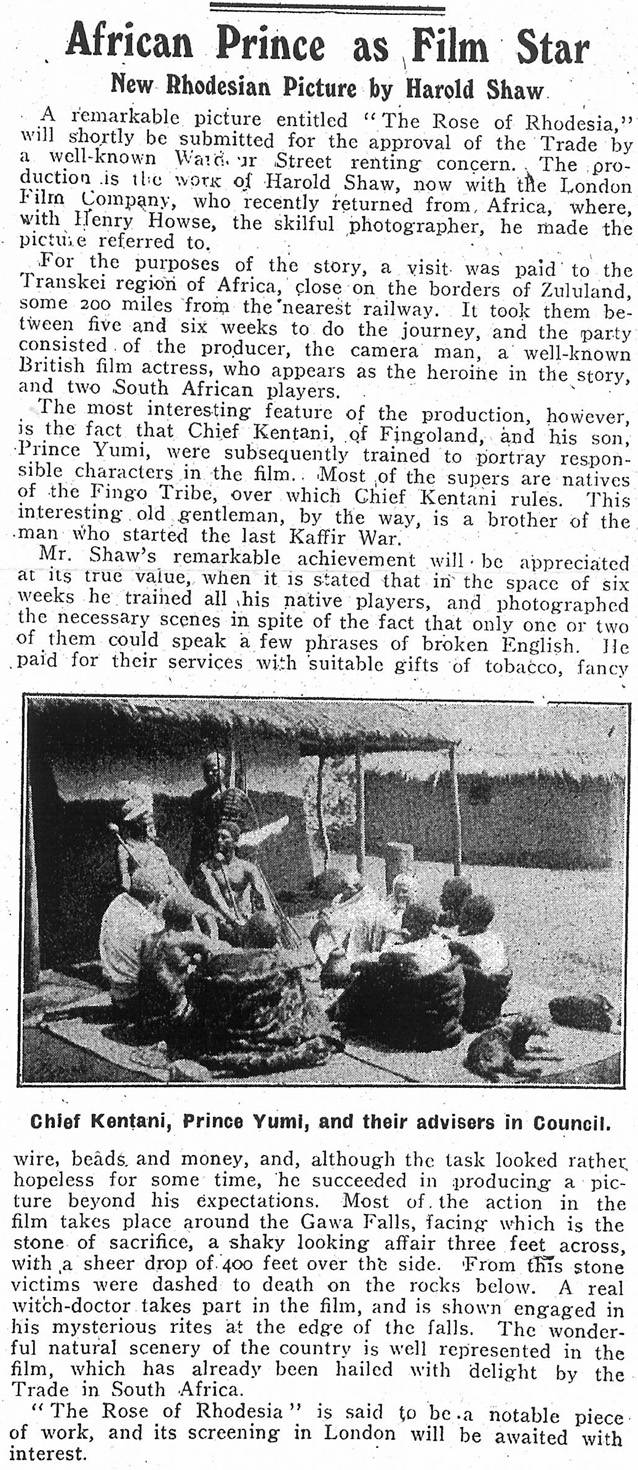

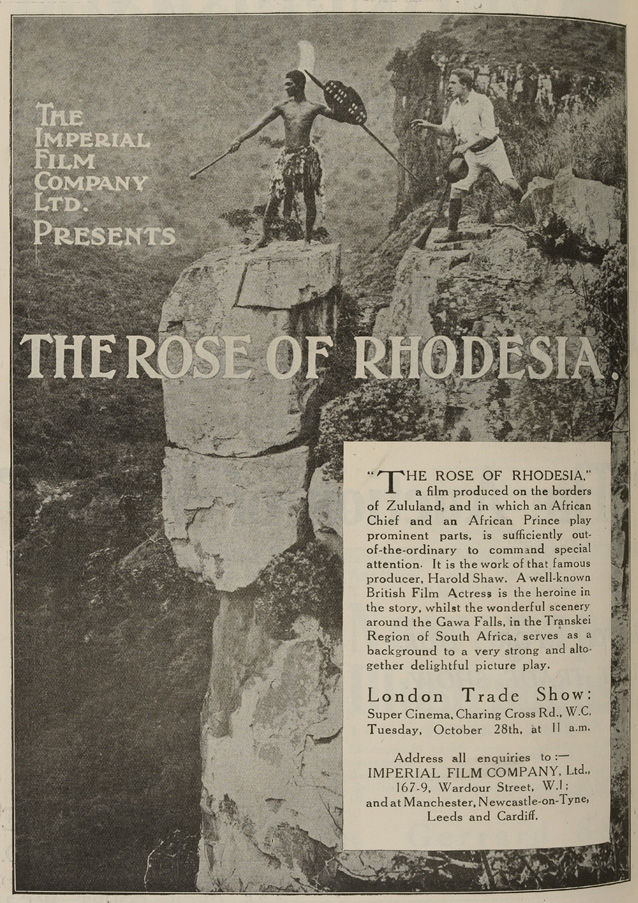

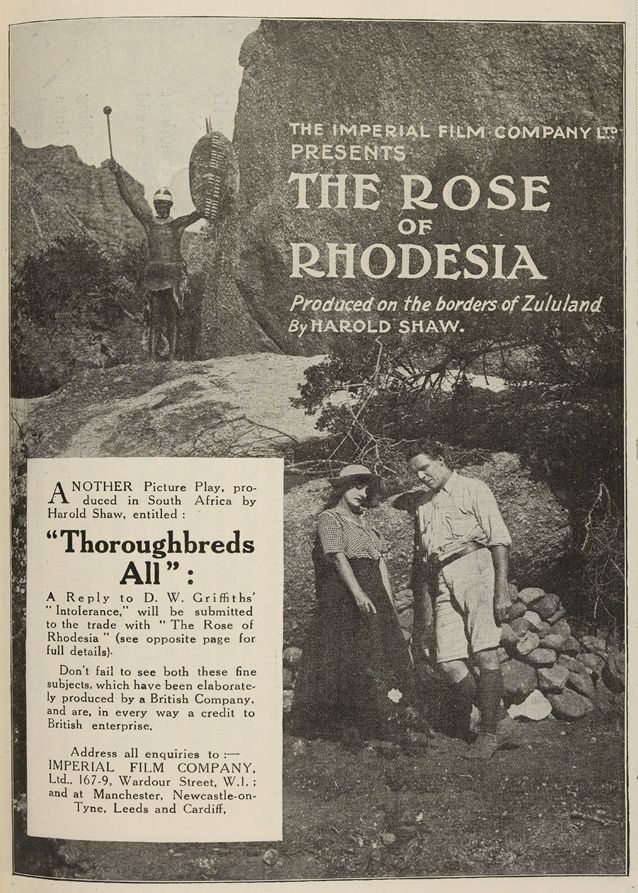

Fig. C9. Double-page advertisement in The Kinematograph Weekly (London), 23 October 1919, 86B-86C.

Fig. C10. The Kinematograph Weekly (London), 86B.

Fig. C11. The Kinematograph Weekly (London), 86C.

C12. Supplement to The Bioscope (London), 23 October 1919, xvi.

“The Rose of Rhodesia”: Forthcoming Trade Screening of a Harold Shaw Production

The Imperial Film Company, Limited, announce that they will submit to the Trade at the Super Cinema, Charing Cross Road, W.C., on Tuesday next, at 11 a.m., “The Rose of Rhodesia,” a film produced on the borders of Zululand, by Harold Shaw, the well-known director, who has so long been connected with the London Film Company.

It will be remembered that some very interesting facts, dealing with the filming of this subject, appeared in a recent issue of this paper. The Ruling Chief of the Fingo Tribe, together with his son, Prince Yumi, play prominent parts in the picture, which is said to be rich in scenic beauty. Most of the scenes were photographed in the neighbourhood of the Gawa Falls, which are some 200 miles from the nearest railway. It took the producer and his party six weeks to trek there, so rough was the country through which they had to pass.

The natives who appear in this production were specially trained for their parts by Mr. Shaw. None of them could speak more than a few half-broken phrases of the English language. As payment for their services, they were given tobacco, fancy wire, beads, swets, etc.

“Thoroughbreds All,” which is said to be a reply to D. W. Griffiths’ [sic] “Intolerance,” and is an excellent racing story, will be submitted to the Trade at the Super Cinema, immediately after the screening of “The Rose of Rhodesia.”

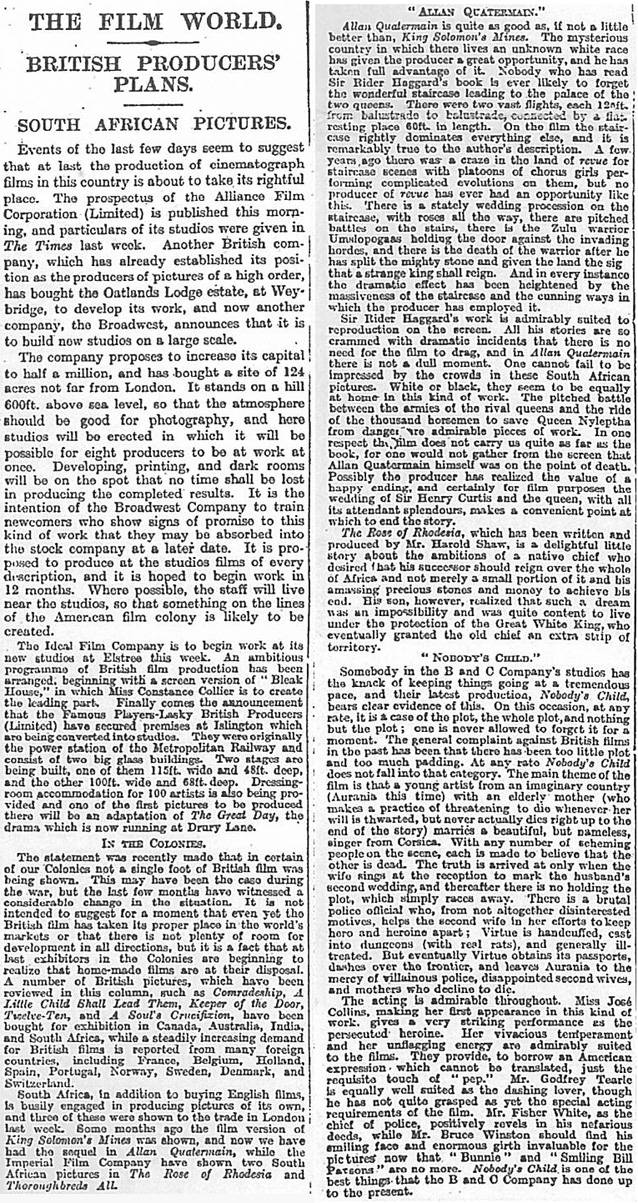

Fig. C13. “The Film World—British Producers’ Plans—South African Pictures”, The Times (London), 3 November 1919, 10.

C14. The Bioscope (London), 6 November 1919, 98-9.

“The Rose of Rhodesia”

Interesting South African picture includes scenes acted by real native players—Thin and rather jumpy story set amid beautiful African scenery—Novel production, containing many features of merit.

Imperial. 5 Reels. Featuring: Edna Flugrath, Chief Kentani, Prince Yumi.

An enormous diamond, intended for presentation to the King by the Karoo Diamond Company, of South Africa, is stolen by Fred Winters, one of the firm’s surveyors, who escapes to the desert, but is overcome by thirst near a water hole. The diamond is taken from him by a follower of the black chief Ushakapilla, who adds it to his treasury for the war he intends to wage if the “Great White King” will not grant his tribe a desired concession of land. Recovering to find the stone gone, Winters goes into partnership with Bob Randall, a prospector who lives with his daughter, Rose, in a hut near the native kraals. Rose becomes engaged to Jack Morel, son of an old missionary, who is assisting Ushakapilla with the latter’s petition for a territorial grant. The death of the chieftain’s son while hunting with Jack, is accepted by the old native as a sign of God’s displeasure with him for plotting rebellion. A letter from the English Government, acceding to his request for land, confirms this view, and, in gratitude, Ushakapilla presents the stolen diamond to Jack and Rose, who are enabled to get married by the big reward they receive for returning the stone to its owners.

The outstanding feature of this rather unequal production is the realistic and delightful study it offers of the life, personal characteristics and surroundings of a Native African tribe. The principal native parts are played by genuine blacks of “royal” blood—Chief Kentani and his son, Prince Yumi—and, although the episodes in which they figure have no very important bearing upon the story, the quaint but effectivenaïveté of their acting is a histrionic curiosity which should not be missed.

The story of the film is thin, conventional and rather clumsily constructed, but the gorgeous African landscapes against which, for the most part, it is set, invest the plot with an interest it would not otherwise possess, whilst the native element is as novel as it is charming. Parenthetically, we suggest that preliminary titles should be added to stress the genuineness of these scenes. One rather wishes, in fact, that Harold Shaw, who produced the film, had chosen a plot which would have made the natives the central features of the play.

For the rest, there is not a great deal that is necessary to say concerning the picture. the white players scarcely compare with the blacks in interest or even effectiveness, while the incident of the diamond robbery is too stagey to be very thrilling. The photography of the exteriors is admirable, but the interiors suffer from inadequate lighting. At present rather ragged and jumpy, the film could be greatly improved by careful editing.

“The Rose of Rhodesia” is a decided novelty.

C15. The Kinematograph Weekly (London), 6 November 1919, 115-16.

The Rose of Rhodesia.

Imperial. Featuring Edna Flugrath. Five reels. Released, November 1919.

Combined with a carefully constructed story and skilful and interesting characterisation, “The Rose of Rhodesia” has the qualities of an educational and of a “scenic”. One of the most notable points is the good acting of the natives in their Zulu kraal, and much of the grand scenery (crags, precipices, and waterfalls) is of a kind which could only be taken in Rhodesia. At the same time, / in the following story, there is a pleasing touch of romance, pathos and humour, with a slight suggestion of irony, all of a moderate kind and artistically presented.

A native African chief who has, without success, petitioned the English Government for more land on the other side of the Zambesi, persists in the ambition that his son shall rule all over Africa. His son, however, loves peace, and hunts with the son of a local missionary. the chief sends some of his subjects to their diamond mines, telling them to bring back treasure so that he can buy ammunition to drive the whites out. One of the natives finds, lying exhausted in the desert, a white man who has stolen the enormous diamond, “Rose of Rhodesia,” steals it from him and brings it to the chief. The white thief becomes partner of a dissatisfied gold digger who has a novelette-reading daughter named Rose. At first she makes a hero of the thief. The son of the chief is killed while hunting with the son of the missionary, and the chief is persuaded to consider this a judgment of the King of Kings, and renounces his ambitions. At the same time he receives a reply from England granting the land which his tribe needs. The chief makes a present of the diamond called “Rose of Rhodesia” to the girl Rosa on her engagement to the son of the missionary. She returns it to the people from whom it had been stolen, and receives a very large reward. The last scene, in the nature of an epilogue, shows the missionary’s son, become clergyman, trying to compose a sermon while the mother is doing her best to quiet four young children.

This unconventional epilogue is a daring but welcome piece of realism. At the start an impression is given that there is to be strong drama founded on a conflict between the interests of the natives and those of imperialism. But, in reality, the “native question” does not develop. The producers have carefully avoided the danger of giving offence to partisans of either side. In doing so they have left the story rather devoid of “punch,” but that does not matter to those who prefer artistic merit to thrills. The story is entirely pleasing, both as a whole and in detail. The native character is shown in a pleasing light. Even the black thief saves his victim’s life by giving him water. The acting both of Chief Kentani and Prince Yumi as the Chief and his son is extraordinarily good. In fact it seem that they simply live their parts. The chief characteristics of the son are his almost childlike delight in hunting, his affection for his white companion, and his unexpected bursts of humour. As he has never faced the camera before, it must be assumed that acting comes natural to him. Kentani is perhaps best in the scene of the chief’s mourning for his son. The scene of the burial of the young native and the planting of a rose slip in front of his tomb is one of true and artistic pathos. Edna Flugrath gives an interested study of a girl naturally sensible, but imbued with the nonsense of a novelette, her father’s drunkenness and his failure. She is particularly good in her youthful coquetry towards the thief when she takes him to be a novelette hero.

The first theft of the diamond is an original and ingenious piece of work, and altogether the three threads of the plot are woven together with exceptional skill. In spite of the lack of thrills or suspense in the working out of the story, it is pretty sure to please the crowd, as it certainly will the select, because of the fine scenes of native life and customs, which are a credit to the producer—Harold Shaw.

Created on: Tuesday, 18 August 2009