Over the past twenty-five years, several filmmakers throughout the world have departed from classical narrative formulas to embrace the intertextual as well as intratextual complexities of “episode films” (feature-length motion pictures each made up of several discretely demarcated stories, sketches, anecdotes, or variations on a theme). In doing so, such disparate auteurs as Ventura Pons (Spain), Hong Sang-soo (South Korea), Rodrigo García (United States), Jim Jarmusch (United States), François Girard (Canada), Alejandro González Iñárritu (Mexico), and Petr Zelenka (Czech Republic) have created polyphonic works whose internal fragmentation provides a structural foundation for expressing psychological uncertainty, epistemological ambiguity, perspectival disjuncture, and thematic reverberation while suggesting an affinity for various literary and artistic avant-gardes of the twentieth-century. This essay attempts to account for two unique strains of cinematic episodicity gaining currency within the critical community, each rooted in avant-garde practices that predate contemporary film. In the process of unpacking these alternative approaches to storytelling, I explore particular texts that have already been the subject of hypotheses about the nature of cinematic narration, albeit often without being situated within either a broader art-historical context or a lineage that recognizes the significance of earlier anthology, omnibus, portmanteau, and sketch films.

After briefly discussing Jorge Luís Borges’s importance to cyclical and subjunctive cinematic forms in the first section of this essay, I focus on a select few episode films whose stories fork off from one another and provide alternate visions of a single character’s immediate future. Unlike many episodic narratives in the multi-director (omnibus) and multi-character (ensemble) molds, these works typically revolve around an individual protagonist or a couple rather than a broad swath of humanity, although the stories they tell – each one rendered in the conditional tense, each one different from the others in some significant way – are aligned in a similarly serial pattern. However, if we think of the interstitial moments between the episodes of a representative omnibus production like Quartet (1948) as being akin to the conjunction “and” (“The facts of life” and “The alien corn” and “The kite” and “The colonel’s lady”), then the slivers of time between stories in a forked-path film like Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Blind Chance ( Przypadek, 1982) are akin to the word “or.”

After exploring some of the narratological aspects of Kieslowski’s Blind Chance, a three-episode film set in pre-Solidarity Poland that controverts the roles of both fate and chance in shaping a young man’s life, I move on to a brief discussion of Run Lola Run (Lola rennt, 1998). Director Tom Tykwer’s kinetic updating of the Polish film tracks the titular heroine’s titular sprint through Berlin to procure the 100,000 German Marks that her smuggler boyfriend has lost, each of its three episodes offering a different outcome to the kernel story. Using Slavoj Zizek’s writings on these two films as an interpretative and structural model, I then ruminate on the applicability of episodicity and “forked-path thinking” within critical studies. Increasingly, theorists, historians, and scholars have incorporated in their analytical writings modes of fragmentation, branching, and discursivity that reflect a broad cultural-aesthetic trend, one that is consonant with modernist as well as postmodernist reading strategies.

By assimilating the discombobulated structure of episode films and turning it into a rhetorical mode on the page, such otherwise disparate writers as Zizek, Peter Wollen, Susan Sontag, and Robert Ray evince a collective interest in new channels of communication that appear to be naturally amenable to the subject of forked-path narratives and are therefore instructive of the ways in which critical discourse can be made to “fit,” like a glove over a hand, the otherwise ungainly anthology, omnibus, portmanteau, and sketch forms that have often been derided by unsympathetic reviewers as hit-and-miss hodgepodges. Given the high degree of antipathy directed toward episodic narratives, I feel that it is important to stress the ways in which fragmentation, discursivity and decentering – when joined to more traditional interpretative paradigms (such as Formalism, Marxism, Structuralism, Feminism, and Psychoanalysis) – can help us meet the unique hermeneutic challenges set forth by episode films, which are torn between the singular and the multiple, integration and disintegration.

The second half of this essay builds upon the themes of repetition and change, similarity and disjunction, so central to cyclical and forked-path narratives, to explore a similar subset of episodic cinema. This branch relies upon a cubist or multi-perspectival approach to storytelling that disperses point-of-view across either a wide spectrum or a select group of individuals whose contrasting memories portend their ultimate non-compatibility on an emotional or physical level. Like episodic films such as Blind Chance, which ask “what if” such-and-such were to happen, cubist narratives such as Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), Hong Sang-soo’s Virgin stripped bare by her bachelors (O! Su-jong, 2000), and Zhang Yimou’s Hero (Ying xiong, 2002) double back on themselves and ask the spectator to accept a potentially false proposition “as if” it were true (and vice-versa), thus casting light on a trademark of this subgenre: its reliably unreliable narration.[1] This calls into question not only the plausibility of an objectively rendered “primal scene,” but also more traditional or transparent narratives’ claim to truth. As we shall see, distinctions between forked path and cubist narratives are fine and fraught with complexities. However, the relationship between the two can be better ascertained through a cross-media contextualization that sees cinema as only one of several forms of cultural production mired in the previous century’s aesthetic traditions, and thus linked to literature, theatre, painting and other visual arts.

A Borgesian Branch of Cinema: Cyclical and Subjunctive Narratives

As early as 1941, Argentinean writer Jorge Luís Borges anticipated the advent of hypertext fiction and subjunctive cinema when he published The Garden of Forking Paths (El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan). This collection of eight stories, subsequently included in the 1944 volume Ficciones, not only proved to be influential on several literary and philosophical movements,[2] but also provided a template for subsequent cinematic and computer Web-based attempts to convey an idea of “the infinite” through finite structures. Much of what has been written about Borges’s collection focuses on the last of the eight stories, “The garden of the forking paths,” in which a Chinese-German double agent in Britain during the first World War, Yu Tsun – upon taking the gently winding road away from his pursuer – imagines “a labyrinth of labyrinths, a maze of mazes, a twisting, turning, ever-widening labyrinth that contained both past and future and somehow implied the stars.” [3]

Yu Tsun reflects back on the garden of his dead ancestor, Ts’ui Pen, a metaphysician who spent thirteen years of his life writing a book of infinities. In the village of Ashgrove, Yu Tsun meets British Sinologist Stephen Albert, who has collected and translated Ts’ui Pen’s manuscript into an inexhaustible novel in which the hero dies in one chapter yet is “alive again” in the next. Initially dumbstruck by the idea that “a book could be infinite,” Albert surmised that it could only be “a cyclical, or circular, volume, a volume whose last page would be identical to the first, so that one might go on indefinitely.” He likens it to “that night at the center of the 1001 Nights, when the queen Scheherazade (through some magical distractedness on the part of the copyist) begins to retell, verbatim, the story of the 1000 Nights, with the risk of returning once again to the night on which she is telling it – and so on, ad infinitum.”[4]

This description of a circular, never-ending narrative might remind readers of the British film Dead of Night(1945), produced by Michael Balcon at Ealing Studios just a few years after Borges’s story was first published.[5] In this somewhat-surreal, five-episode omnibus film featuring the contributions of four directors, an upper-middle-class farmhouse is transformed into a hothouse of dread and desire when Walter Craig and five additional guests recount chilling, supernatural episodes in their lives. The frame story, which shows each member of the group of strangers speaking in turn, is reinitiated at the end of the film to suggest an infinity of repetition not unlike that described by Albert in the Borges story. Thus, the terrifying uncertainty at the core of this British picture contrasts with the certainty of endless repetition marked by its frame story, which – like a Chinese box – is a dream containing several dreams, each one filled with flashbacks, each one following the other until the circle is complete.

Other similarities abound, such as the German/British binary that Borges uses to oppose body and mind, physical strength and metaphysical imagination; in Dead of Night, that dichotomy is inversely figured in the guises of two individuals: Dr. von Straaten, an overly rational psychoanalyst, and Walter Craig, the aforementioned protagonist whose uncanny dreamworld cannot be so easily explained away or exorcised.[6] Like Craig, an architect who has been summoned to Pilgrim’s Farm to begin reconstructing the old farmhouse, Albert has devoted part of his life to reconstructing Ts’ui Pen’s puzzling text, the manuscripts of which the Englishman has compiled and translated. Significantly, in trying to grasp the notion that a book could be infinite, Albert conjectures that what Ts’ui Pen had in mind was “a platonic, hereditary sort of work, passed down from father to son, in which each new individual would add a chapter.”

These words conjure the multi-authorial dimensions of Dead of Night and other omnibus films in which different directors each add a new “chapter” to a series organized around a core idea or proposition, thereby suggesting several paths or futures emanating outward from a narrative “center” while, paradoxically, delineating a cyclical pattern indicative of a single future (which, to further compound the paradox, is the past). Ultimately, Stephen Albert puts his faith in the forked-path, rather than strictly cyclical, variety of storytelling, for he realizes that, “In all fictions, each time a man meets diverse alternatives, he chooses one and eliminates the others; in the work of the virtually impossible-to-disentangle Ts’ui Pen, the character chooses – simultaneously – all of them. He creates, thereby, ‘several futures’, several times, which themselves proliferate and fork.”[7]

While most critical discussions of The Garden of Forking Paths highlight the collection’s same-titled anchor story as the most distilled evocation of Borgesian non-linearity and multiplicity, another, less famous story from the same volume provides ample evidence that the author had literally envisioned the process and potential of branching narratives (not to mention reverse-chronological plotting). In his critical essay-pastiche, “A survey of the works of Herbert Quain,” Borges goes so far as to include a multi-pronged diagram of the fake author’s fake novel April March, which begins on a railway station platform and proceeds to move backwards in time while providing alternate possibilities of the preceding action. If Quain and his reverse-order novel are literary constructs, an author and a book invented by Borges to make a particular point about the unrealized potential of fiction, his concept of “infinite stories, infinitely branching” resonates in the real world, where each day we face an almost paralyzing series of endless possibilities.

As suggested above, the forking-path paradigm articulated by Borges in his parable about parallel and possible futures has since been assimilated in the lexicons of hypertext fiction, Web design, and computer gaming – arenas in which non-linearity, infinite branching and complex combinatory patterns have perhaps been most fully realized and consistently utilized.[8] More central to the present discussion, however, are cinematic works that feature forked-path narratives. This type of episode film poses hypothetical conclusions to a single, germinal story-event that is presented early in the frame narrative. Together these different outcomes, rendered as serial episodes, express what could be, would be, or might have been.[9] Similar to Italo Calvino’s 1979 novel If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (which is composed of a series of abortive narrative beginnings leading not to a climax but rather to another beginning), “repeat action” films such as Blind Chance, Sliding Doors (1998), and Run Lola Run fit into this sub-category.

Perhaps the most famous example of subjunctive conjecture in history comes from Blaise Pascal, who in Pensées (1670) muses, “Had Cleopatra’s nose been shorter, the whole face of the world would have been different.” Spanish filmmaker Ventura Pons makes a similar, albeit less monumental assertion in his Catalan-language motion picture To Die (or not) (Morir [o no], 2000). The first fifty minutes of the film present, in consecutive fashion, seven black-and-white vignettes (each roughly seven minutes in length) concerning seven seemingly unrelated people who die, one by one. Pons then follows this apparently irreversible set of existential situations with a thirty-minute hypothetical section (“what if”), which shows how the altering of a single person’s destiny can have a kind of “butterfly effect,” changing the course of events (history on a small scale) and guaranteeing the survival of these initially ill-fated “strangers” (who, it turns out, are connected either tangentially or as close friends and distant relatives).[10]

This latter suite of episodes, filmed in color, marks both an aesthetic and narrative reversal. A kind of asymmetrically skewed palindrome, the film lurches back toward the beginning, with the final episode of the first black-and-white section providing the basis for the first episode of the final color section. Only after that shift has occurred – a moment marked by a black screen on which the words “Not to die” appear – do we realize that the seven episodes comprising the first fifty minutes of the film actually transpired in reverse order (recalling the aforementioned April March as well as reverse-chronology films such as Memento [2000] and Irreversible [2002]). The first scene of the film, which shows a man waking up in the morning and telling a story to his wife about an eighteen year-old boy whose motorscooter collides with a car at an intersection late one night, actually occurs last, after the events within the other six episodes have transpired. His story is thus less a primal act of initiating filmic discourse than a retrospective account of just one of the many events that will assume deeper meanings only after the “what if”/”or not” section unfolds.

Significantly, the teenager involved in the traffic accident is given an opportunity to imagine numerous hypothetical futures for himself in that split second before the crash. As the storytelling husband explains to his wife toward the beginning of the film, “Everything freezes. Someone, not God, nor Heaven nor Providence, just someone freezes that eternal second prior to his brutal death.” A disembodied voice from above then asks the boy, “If you survive, what would you be?” Looking into the sky, the boy responds, “A multinational executive. No, a famous movie star. No, I’d be a multimillionaire, with a lot of people working for me.” At this point the voice asks, “Who would you like to live with?” The boy answers, “A young, pretty, sculptural and lewd blonde…A different one every two-to-three weeks.” When he is asked to describe his ideal home, the boy says, “A luxury apartment in town, a mansion with a private ski slope, a house on a tropical island.”

Besides inspiring the wife of the storyteller to interject with the names “Frank Capra” (an allusion to the 1946 classic It’s a Wonderful Life) and “Charles Dickens” (whose A Christmas Carol was another literary prototype of forked-path possibilities), these multiple answers to single questions remind us that the episode film – a narratological genre that is “polygamous” with its protagonists – is ideally equipped to give us many, if not all, possible futures. This is further underlined by the boy’s choice not to choose any one of the futures that are briefly projected for him to see (leading up to either a “a rebellious, poetic, immediate death” or “a sweet death after seventy-five years of boredom and indifference”). This decision not to decide, however, simply results in his death by automobile collision, an outcome that is doubly ironic and synchronic given the fact that the man who is telling this story has a potentially deadly heart attack at that very moment.

Sandwiched between this first scene and the final scene of To Die (or not), which returns us to the storyteller having a heart attack (only this time with him surviving, thanks to the efforts of his wife, who is a nurse), the remaining episodes veer wildly from meditative drama and outright tragedy to slapstick action and screwball romance. Taking us from [1] the married couple to [2] a drug addict and his interventionist sister to [3] an insufferable mother and her pre-teen daughter to [4] a nurse and her dying patient to [5] a depressed, suicidal woman and her offscreen son (the motorcyclist seen earlier) to [6] a red-light-running police officer and her male partner to [7] a hired killer and his wealthy target before reversing the order of those episodes in the “what if”/”or not” section (which shows the heretofore hidden linkages between these characters), the film provides disconcerting evidence that our lives often hang by a string, that “fate” can intervene when one least expects it and open up new paths toward not one but several futures. Perhaps what is most striking about this and similar motion pictures, such as Smoking/No Smoking, Alain Resnais’s double-barreled 1993 adaptation of Alan Ayckbourn’s renowned play “Intimate Exchanges” (which provides twelve different endings based on characters’ inability or ability to kick the nicotine habit), is that they actually take the “road not taken.” Such a premise furthermore recalls O. Henry’s 1909 short story “Roads of destiny” (made up of three possible futures faced by the poet-hero), Lord Dunsany’s 1921 play If, and, most recently, Ken Grimwood’s acclaimed 1986 novel Replay.

Like Dunsany’s play, both Blind Chance (Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Polish-language progenitor of this cinematic trend) and Sliding Doors (Peter Howitt’s English-language knockoff) hinge upon the iconography of departing trains. The question of whether or not the protagonists in these films catch their trains serves as a narrative catalyst, the crucial point of departure in depicting not one but potentially several outcomes. However, whereas Sliding Doors is a romantic British comedy about two, rather than three or more, alternate realities involving socially mobile and physically beautiful men and women (presented in cross-cut fashion), Kieslowski’s tripartite film delves into philosophical questions about one’s fate in a troubled socialist bloc state where opposing political forces relentlessly vie for public and personal support.

After making Camera Buff (Amator, 1979), a reflexive jab at factory corruption, and having already established the motif of men trying to catch departing trains and trams in his black-and-white shorts from the late-1960s, Kieslowski mounted Blind Chance, a film whose openly critical attitude toward Communism did not sit well with his government.[11] All three of the film’s episodes concern young medical student Witek Dlugosz as he faces different sets of obstacles in the politically volatile period of the late 1970s (leading up to the era of the free trade union known as Solidarity). After a dozen brief, fragmentary scenes play out during the film’s prologue – flashbacks showing key yet quotidian (perhaps even imaginary) moments in the protagonist’s life – the first episode begins.

His father recently deceased, Witek has impulsively decided to abandon his studies and set out on his own. The combined freedom and fear built into that decision is visually conveyed in the film’s most indelible scene, one that will be repeated twice more over the course of the cryptic triptych, with significantly different outcomes each time. Accompanied by composer Wojciech Kilar’s driving score, Witek dashes through a station, desperately attempting to catch a departing train bound for Warsaw. He bumps into an old woman and nearly collides with a disheveled man, yet he manages to grasp onto the handrail at the last possible moment and climb aboard the train. Not coincidentally, this scene recalls an early passage in Borges’s story “The garden of the forking paths,” when Yu Tsun, a self-proclaimed “connoisseur of mazes,” flees his adversary Captain Richard Madden at a station – the former just barely making it onto the departing train as the latter runs “vainly, out to the end of the platform,” but is unable to catch up.[12]

Aboard the train, Witek meets Werner, an idealistic and devoted Communist several years his senior who soon introduces him to a Party functionary, Adam, and convinces him to join. Another Party official sends the new recruit to a drug treatment hospital where a sit-in demonstration is taking place. A pawn in a political game that could have dire consequences, Witek has been asked to act as an intermediary between the politburo’s functionaries and the young dissidents, who have staged a mutiny at the hospital and taken three doctors sent by the Party as prisoners. Ultimately, Witek succeeds in rescuing the three workers from their gasoline-soaked cage, but fails to win the love of his one-time girlfriend Czuszka, with whom he has been reunited. Czuzska, a dissident herself, is arrested by the Polish Secret Service toward the end of this episode, apparently because Adam has learned of her underground activities through his association with Witek. The episode ends with our disillusioned apparatchik and other members of the Party preparing to board a plane to Paris, only to learn that – because Solidarity strikes have broken out across Poland – they will not be able to leave the country as planned.

At this point – the fifty-five minute mark, nearly midway through the film – Kieslowski returns us to the train station and replays Witek’s mad dash down the platform to the same musical accompaniment. This marks the beginning of the second episode, which explores what Witek’s life might have amounted to had he missed the train and become a member of the anti-Communist underground student movement. Having been arrested after getting into a scuffle with a station guard, he is sentenced to a work brigade, performing thirty days of community service planting flowers at a large estate. One of the members of the work brigade, Marek, is a political dissident who – like Werner in the first episode – convinces Witek to side with him. Besides dedicating himself to the cause and running the secret printing press used to disseminate samizdat leaflets and other illegal literature, Witek surrenders himself to God, becoming baptized into the Christian faith after meeting one of Marek’s associates, a wheelchair-bound priest named Stefan. He also falls under the spell of Vera, a married Jewish woman whose brother Witek had known during the student uprisings of the late 1960s. This episode ends much like the first one: Witek is set to take a flight to Paris, where a Catholic Youth Conference will be held, but is denied a visa because he did not provide the government with the names of his agitator friends.

Once again, the film recapitulates the train station scene. And once again, Witek misses his train. Only this time, no fisticuffs with the guard ensue. Instead, Olga, his current love interest who was waiting at the station, convinces him to pursue a medical career. Succumbing at last to his dead father’s wishes, Witek dedicates his life to his new wife and child as well as to his work in medicine. With contentment, however, comes complacency. As an avowed “non-believer,” he steers clear not only of religion but also of the many recruiters vying for his allegiance. Members of both the dissident group and the Party approach him, but he steadfastly refuses to join either of the two. He does, however, accept an offer by the medical school’s Dean to attend a surgeon’s conference in Libya. When Witek arrives at the airport on his way to Paris, Kieslowski cuts to various people in the crowd whom viewers will remember from the preceding episodes.

This decision by the filmmaker to link the three divergent tales in such a way suggests a metaphysical synchronicity, something fans of Kieslowski’s chromatic trilogy – Blue (Bleu, 1993), White (Blanc, 1994) and Red (Rouge, 1994) – not to mention the more elliptical The Double Life of Veronique (La double vie de Véronique, 1991) have come to appreciate as an authorial staple. Each of Blind Chance‘s three stories culminates with the possibility of flight, but only this third episode shows Witek successfully boarding the plane (which is bound for Libya via Paris). However, as foretold by the dean, Witek’s first trip abroad will also be his last. Upon takeoff, the jet airliner bursts into flames, bringing an explosive end to an otherwise understated film. The image of the mid-air explosion provides an important clue about a heretofore-unclear section of the film. At the beginning of the prologue, Witek unleashes a kind of primal scream while seated, one presumes, in a plane. After the camera dollies forward into the darkness of his throat, the inexplicable image of him shrieking gives way to a shot of casualties being brought into an emergency room. Such a presumption may be correct, for in retrospect (after having seen the film’s final moments) those early images appear to be a result of the explosion. If this is the case, then the film’s forked-path presentation of multiple possibilities circles back to the beginning in a way that recalls Dead of Night and other cyclical narratives.

In his thorough delineation of conventions found in forking path (or “multiple draft”) narratives, David Bordwell discusses this cyclical structure, which he argues privileges the final future, the only one of the three to end with an airplane explosion. However, such a reading – while entirely plausible – takes on faith the possibility that Witek, or anyone else for that matter, could have survived an explosion that might just as likely have left his body beyond repair, a ravaged, unsalvageable remnant of his former self. Bordwell is fundamentally right, though, not only in arguing that diverging paths typically adhere to “a strict line of cause and effect” (with no further branching or bifurcation after the initial fork), but also in pinpointing both the “primacy effect” that results when the first episode “shapes our expectations about what follows” and the “recency effect” that occurs when the last episode “modifies our understanding of what went before.”[13]

It would seem, then, that there are two episodes, rather than one, being favored in Blind Chance: the first for establishing “a benchmark” that sets down “the conditions that will be repeated, varied, omitted, or negated in subsequent versions,” and the last for being the “final draft, the one that ‘really’ happened.” The middle section would thus appear to be less consequential than the others, given the weight of those bookending episodes. Nevertheless, it yields as much important information about Witek’s personality as the other episodes, information that filters into the surrounding scenes (especially those involving either one of the three different women with whom he forms relationships: Czuszka, Vera, and Olga) and colors how we feel about his death at the end.

Like John Fowles’s 1969 novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Kieslowski’s Blind Chance has three different endings. However, only one – the last – has a real sense of finality, due not only to the airplane explosion but also to the fact that it coincides with the end of the film. This hermeneutic privileging of the final episode suggests that it is more “real” than the others; that it retroactively consigns Witek’s political involvement and dissident action in the preceding episodes to the realm of the imaginary and hypothetical (whereas noninvolvement and apathy become the sine quon non). Paradoxically, these three separate narratives are arranged in a linear yet reiterative fashion, their sequential ordering suggesting an emotional maturation and psychological development on the part of Witek. However, we see that, in retreating from politics and withdrawing into an uncomplicated domestic life and private profession, Witek has regressed to a more sanitized and distant point in his life, one that is ironically brought to a premature end by an explosion (which may or may not be an act of terrorism, one can only guess – hence the non-conclusive conclusion). Nevertheless, these episodes do not really cancel one another out, at least not in the memory of the spectator. Instead, they collectively add up to an evocative portrait of the main character’s complex personality.

|

|

|

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 | Figure 3 |

Aiding our attempts to draw out thematic and stylistic comparisons among the three stories is Kieslowski’s use of specific visual motifs, which carry over from one episode to the next. Besides each episode’s foregrounding of surrogate fathers, mentor figures, romantic partners, passports, illegal literature, secret meetings, and the threat of insurgency, certain images and character movements are repeated.[14] For instance, the curved motion of a Slinky toy descending Werner’s staircase in episode one is later evoked in the rainbow-like arc of the dozen or so balls being juggled by two men in episode three. Each of the episodes, besides showing Witek running (not only for the train, but also for the bus and other people), includes a shot of him slumping to the ground out of shock and resignation: first when Czuszka is picked up by police and taken away [Figure 1]; then when the underground printing press is confiscated by the authorities [Figure 2]; and finally when he learns that Olga, his bride-to-be, is three-months pregnant [Figure 3]. This repeated image of Witek’s knees buckling once again complicates any sense of emotional maturation, suggesting that he is retreating each time into a near-fetal position.

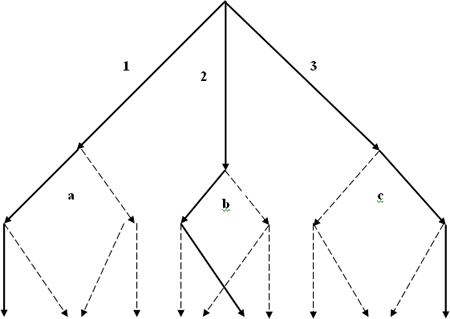

Narrative possibilities in Blind Chance:

A visual description of realized and unrealized plotlines (title for diagram)

Figure 4: This simplistic rendering of the actual and possible bifurcations present in Blind Chance is designed to illustrate the fact that forking paths may lead to consequences that intersect or run parallel, yet rarely provide additional forks in the road. Nevertheless, while those imbedded departure points are rarely explored/exploited after the initial bifurcation, they exist as possibilities in the spectator’s mind, stimulated as the latter is by the prospects of (unfulfilled) infinity. (description of diagram)

As the above graph illustrates, Kieslowski may provide us with three separate scenarios tracing out Witek’s immediate future, but he does not show the many potential narratives that could have been spun out from other critical junctures or decision-making crossroads within the three episodes [Figure 4]. As illustrated by the broken arrows, these plot potentials must be dispensed with offscreen and in the imagination of the spectator due to the temporal limitations of the feature-length film as well as the artistic decisions made by the filmmaker, who opted to follow not the infinite possibilities of narrative (an impossible, only hypothetically posed venture regardless) but simply the three linear paths toward either death, deadlock, or indifference (itself indicative of moral decay). Instead, Kieslowski cedes that task to the audience, who may wonder, for instance, what might have happened had Witek intervened as the police were taking Czuzska away in episode one (indicated in the above graph by the letter “a”). What might have been the outcome had Witek decided not to visit a woman in episode two – the devout Christian to whom he delivers a payment of 7000 zlotys and who unwittingly sends him on his spiritual quest (“b”)? Had Witek not agreed to stay on at the Academy (as suggested by the Dean), would his life have taken a less deadly turn (“c”)?

Each episode finds Witek being forced to make significant decisions that will have an impact on the rest of his life, whether it is choosing to climb down the terrace of the hospital with the medical staff he rescued in episode one, or opting to fill in for the Dean at a conference to be held in Libya. Unlike Ts’ui Pen’s labyrinthine manuscript in “The Garden of Forking Paths,” a contradictory collection of tales in which all the possible outcomes occur, Blind Chance can only gesture towards rather than contain infinity through its episodic emplotment of three narrative possibilities. Although Kieslowski expressed dissatisfaction with the resulting film (a feeling that he attributed to his own script’s “flaws”),[15] few other works lay out so starkly the role of fate and destiny in shaping one’s existence. The major questions this film raises have to do with chance, determinism and freedom of choice, three contending factors in a person’s life that are nevertheless consolidated at the end. Despite the different situational contexts in which we find ourselves, all roads lead to one destination: death. This is what Kieslowski himself found most appealing about the film, saying, “The third ending is the one which means the most to me – the one where the aeroplane explodes – because one way or another, that’s going to be our fate. It’s all the same whether this happens in an aeroplane or in bed, it doesn’t matter.” [16]

Predestination is similarly highlighted in another forked-path film, albeit with less fatalistic overtones. Run Lola Run, a critically and commercially successful German-language production directed by Tom Tykwer, begins with the swinging of a pendulum and the speaking of the words, “The ball is round, the game lasts ninety minutes.” [17] The ludic aspects of the text are on display in each of its three successive episodes, which find a twentysomething woman racing against the clock to save her boyfriend who lost 100,000 deutsche marks on the U-Bahn (payment for a smuggling job that he was to deliver to a drug lord). Indeed, the first of Lola’s sprints through Berlin to her father’s bank comes after a printed epigraph (attributed to a World Cup-winning soccer coach from Germany, S. Herberger) appears onscreen, reading “Nach dem Spiel ist vor dem Spiel.” Translated as “After the game is before the game,” these words not only prepare the audience for subsequent images of a roulette wheel and the pinball-like action of the heroine, but also indicate the termporal paradox at the heart of most cyclical and forked-path narratives in which one episode begins as soon as another has ended (leaving, at least in this breathless film about deadlines, “hardly a pause, and even the pause is preparation for the next game”).[18] Insfoar as Lola’s first two failures allow “for the continuity of play,” then, as Jamie Skye Bianco points out, losing the game ironically becomes a form of “winning,” one that “is not equivalent to psychoanalytic lack” but rather is indicative of memory’s “fullness” in terms of “what has already occurred, what is perceptually present and what is virtually to come.” [19] Only at the end, once Lola has “won,” does a sense of “permanent loss” intrude upon the film’s ludic maneuvers.

As Slavoj Zizek remarks, the three narratives comprising the film, each lasting roughly twenty-five minutes and driven by a techno-ambient soundscape combining adrenaline-pumping backbeat and the crimson-haired heroine’s heartbeat, emulate the existential coordinates and formal characteristics of the typical “survival video game.” Blessed with three expendable “lives,” Lola experiences the present as a potentially erasable set of actions that can be redone. Zizek emphasizes that, however visually and aurally dissimilar Run Lola Run and Blind Chance are in terms of their stylistic and tonal properties, the two films’ “formal matrix is the same.” He elaborates: “[I]n both cases, one can interpret the film as if only the third story is the ‘real’ one, the other two staging the fantasmatic price the subject has to pay for the ‘real’ outcome.”[20] There is a difference, though: In Tykwer’s film, the first episode ends with the death of Lola’s boyfriend (he is run down), the second with her own death (she is shot), and the third with her successful accretion of 100,000 German Marks capped by a happy ending in which boyfriend and girlfriend – noticeably more mature than she had appeared in the previous two episodes (as if she has learned from past mistakes) – reunite.

This rather traditional dénouement to an otherwise unconventional set of narrative possibilities stands in marked contrast to the conclusively non-conclusive and fatalistic ending of Blind Chance, which literally explodes the potential for additional stories yet, like the scattered fragments of the plane, leaves certain unanswered questions in the air. Thus, while Run Lola Run playfully engages the theme of death and ranges wider in its deployment of multiple film stocks, digital manipulation, animation, and other stylistic flourishes, Kieslowski’s film plunges deeper into the underlying ambiguities of a cinematic form that is well suited to elucidate multiple viewpoints and contradictory attitudes about a given nation’s sociopolitical system or its citizens’ ethical beliefs.

Run Zizek Run: Episodic Criticism

In the series of images that follows Witek’s presumably mid-air primal scream (a prolonged “No!”) at the beginning of Blind Chance and precedes his first attempt to catch the departing train, the woman whom we will later come to know as Olga watches the dissection of her former teacher at the medical school that she and Witek attend. As the knife slits the skin and opens up the woman’s body for all to see, Olga becomes visibly shaken and leaves the room. Although she does not particularly care for her teacher, Olga feels that she herself is being cut up – a sentiment that she later shares with Witek in the third episode. As much as this act of corporeal incision reverberates with this secondary character’s internal conflicts, it suggests even greater implications for the body of the cinematic text, which not only is cut up into three separate sections but also has been the subject of much critical dissection. Perhaps no one has been as penetrating yet discursive in his examination of the film as Slavoj Zizek, author of The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieslowski Between Theory and Post-Theory.

In the fifth chapter of this Marxist-Lacanian investigation of suture and cinematic materialism, titled “Run Witek Run,” the skeptical Slovenian theorist argues that, according to the deterministic logic of the narrative, “Witek necessarily misses the train, hits the railway guard, catches the train.”[21] He explains: “This paradox of the atemporal choice accounts for the ambiguous tension between chance and necessity in the Kieslowskian universe of alternative realities: while the choice is radically contingent, determinism is complete within each of the three realities of Blind Chance.“[22] Ironically, by highlighting the film’s “metaphysical-existential vision of the meaningless chance events which determine the outcome of our lives,”[23] Zizek betrays his own critical agnosticism, which manifests in this and other open texts that – like Kieslowski’s film – explode “the form of the linear, centred narrative and [render] life as a multiform flow.” In a sense, Zizek sprints through several sets of hypothetical conclusions, the breathless pace of his thinking similar to the nonstop movement of the title character in Tykwer’s forked-path narrative Run Lola Run.

In The Fright of Real Tears and several other texts, Zizek’s mode of inquiry reveals an affinity for episodicity, switching gears with a lightning pace and rhetorical grace. Even within a single paragraph he is able to segue from one historical epoch or theoretical touchstone to another, spinning not out of control but rather a compelling narrative out of disparate and unexpected names, dates, and events. In the space of three contiguous paragraphs in The Fright of Real Tears, he couches a brief discussion of Pascal, Chateaubriand, Adorno, Schelsky, the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal, John Ford’s magisterial Fort Apache (1948) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Kevin Costner’s box-office bomb The Postman (1997), post-apartheid South Africa, Heidegger and the Holocaust (in that order).[24] Similarly, in his analysis of Blind Chance, he veers off the subject to touch on Rudolph Maté’s No Sad Songs for Me (1950), Chris Columbus’s Stepmom (1998), King Vidor’s Stella Dallas (1937), Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier, Goethe’s Elective Affinities, and Guy de Maupassant’s work.[25] An eclectic mishmash of movie references, literary bons mots, and philosophical reflections, Zizek’s omnibus-like discourse dips as freely and habitually in the “shallow” end of “low” culture as in the deeper, more profound waters of “high” culture. This juxtaposition of high and low is actually not so radical in the context of postmodernism, the appearance of which (in cultural, political, and intellectual spheres of life) contributed to the late twentieth-century deconstruction of traditional genres and hierarchies as well as the increased acceleration of culture and simultaneity in the arts.

Of course, one need not be as baroque or hypercitational as Zizek to affect an episodic mode of criticism. Other scholars have adopted fragmented, subjunctive and forked-path reading strategies that run against the grain of convention. Peter Wollen is one scholar in particular who has utilized episodic writing in an illuminating way. As evidence of this, his essay “Rope: three hypotheses” proposes a unique hermeneutic strategy for lifting Hitchcock’s most technically audacious film out of its typical industrial/auteurist milieu so as to deposit it into new historical and aesthetic contexts. Sandwiched between his first and third entries (which speak to the nature of the English private school system and the mobility and claustrophobia found in most Hitchcock films), Wollen’s second splinter-hypothesis – “Rope as an experimental film” – situates the film within the orbit of works like Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1966) and Back and Forth (1969), concluding that Rope is the “ultimate kammerspielfilm.” In a sense, Wollen is running Witek-like through three possible scenarios that both compliment and contradict one another, ultimately resolving himself to be refreshingly unresolved.[26]

Another good early example of critical episodicity occurs in Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation. In her essay about Jean-Luc Godard’s My Life to Live (Vivre sa vie, 1962), an episodic film divided into twelve separate sections that inspires the famous critic to adopt a similarly fragmented reading strategy, Sontag begins by making a distinction between proof and analysis. Breaking her essay into seventeen numbered sections, each one building upon the previous entry yet putting forth, sometimes aphoristically, a new idea or point of epistemological departure, Sontag argues that My Life to Live is an example of properly formalist filmmaking. Rather than engage in a substantive analysis of prostitution’s social implications and historical background, rather than delve into the psychology of one who is forced to eke out a living through sexual transactions, Godard taps into the medium’s material properties so as to highlight particular elements of film form and design that, in conventional narrative systems, often go by unnoticed. Symmetry, inversion, repetition, and doubling are just a few of the most conspicuous elements used by Godard to show – or, as Sontag emphasizes, prove – “that something happened, not why it happened.”[27]

As Sontag states, “the ordinary causal sequence of narrative is broken in Godard’s film by the extremely arbitrary decomposition of the story into twelve episodes – episodes which are serially, rather than causally, related.”[28] She sees his division of the text into twelve discrete fragments (“with long titles like chapter headings at the beginning of each episode, telling us more or less what is going to happen”) as an extension or expansion of Godard’s stylistic techniques (such as staccato editing) that dissociate the viewer from the text, break up the diegesis, and disrupt narrative structures associated with Hollywood. Could we not also see Sontag’s arbitrary fragmenting of her own essay as a way of disengaging herself from traditional analytic models and engaging more directly with a film whose stop-and-start rhythms provide, paradoxically, an experiential approximation of the “real” condition of living in today’s fragmented world?

Perhaps no other film scholar has pursued new critical avenues as doggedly as Robert Ray. In his 1995 book The Avant-Garde finds Andy Hardy, Ray draws upon some of the twentieth century’s most anti-traditionalist traditions to provide alternatives to the overly predictable modes of thinking and writing that lead to repetitive claims or, in their worst varieties, arrogant dogmatism.[29] We should plunge, he argues, into the avant-garde, particularly Surrealism, because its chance operations and associational maneuvers can be put to use, activated in a practical sense. Surrealism’s importance ultimately resulted from the rigor, rather than the seductiveness or eccentricity, of its investigational method – one bound by premeditated rules that led to discovery. By introducing chance, automatism, anecdotes, fragments, and episodicity into the critical act so as to wrench from the periphery of cinematic experience those incidental details that typically go unnoticed – raising the seemingly trivial to a level of significance – we can begin moving beyond the boundaries of an exhausted hermeneutics.

In Chapter One of his book, during a Calvinoesque attempt to stage his introductory remarks in multiple frameworks (a trio of separate beginnings that might remind the reader of the three alternate openings to Flann O’Brien’s 1939 novel At Swim-Two-Birds, not to mention the three futures played out in Blind Chance), Ray proposes revitalizing film studies by moving beyond methodologies that have parasitically latched onto theoretical models such as Structuralism and Psychoanalysis and transformed film writing into a “theoretical machine” running on auto-pilot, propagating stock phrases and sublimating all “irrational” impulses while keeping the transparency of its language intact. Throughout his book, Ray occasionally reasserts the notion that two seismic shifts took place in communication – the first being a segue from oral to alphabetic systems of transmitting ideas; the second being the sudden appearance of a cinematic/electronic culture transplanting the alphabetic – a transformation that eventually posited a postmodernist hyperawareness of the image and its relation to self. Connected to this is the notion that typographical contrivances, such as lists and indexes, have particular effects on writing and reading that should be taken into consideration, and furthermore – as fragmented yet unified forms – can provide the structural foundations of episode films.

Although academic film writing concerns itself with a medium that contributed to the ascendancy of visual literacy, scholars have been slow to incorporate the cinematic and episodic in their own articles, books, and lectures. Ray asserts that Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Projects, which brims with collage and montage, was “the great unbuilt prototype of a new, explicitly cinematic criticism,” and goes on to retroactively link Benjamin, as well as John Cage, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Derrida, to the Surrealist camp; suggesting that they – in addition to André Breton and Louis Aragon – were most sensitively attuned to photography’s ability to recast, cut up, or liquefy literary forms. Although Ray’s provocative and experimental method is still in a state of infancy, and while it certainly begs several outstanding questions, it points toward new heuristic pathways that run parallel to those posed by episode films, particularly omnibus productions such as Dead of Night and, more recently, Maldoror (1997), a German-British adaptation of Comte de Lautréamont’s avant-garde verse novel Les chants du Maldoror (1869) that can be likened to the Surrealist experiment known as the cadaver exquis. Indeed, the “exquisite corpse,” a parlor game popular among artists such as André Breton and Tristan Tzara, produced (through collective authorship and collaborative participation) images of combined unity and fragmentation recognizable to audiences of episode films. [30]

Art historians have likewise begun to latch onto the idea of critical episodicity, something suggested by the titles of such books as Whitfield J. Bell’s A Cabinet of Curiosities: Five Episodes in the Evolution of American Museums (1967) and T. J. Clark’s Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism (1999).[31] Coincidentally, the latter text – a selective tour through nineteenth- and twentieth-century art – not only includes one of the richest historical analyses of Cubism ever ventured, but also concludes with a nod to one of the classics of episodic cinema: Roberto Rossellini’s Paisà (1945), a blown-up image from which the author admits to having on his wall.[32] Like the Italian Neorealist’s film, Clark’s book has a basic form whose “brokenness and arbitrariness” was intentional. He envisions his chapters or “episodes” (“Pissarro in 1891,” “UNOVIS in 1920,” “David in Year 2,” “Picasso in the first flush of Cubism”) as “items from a modernist dig,” and later describes his own analysis of Cubism as a

medley of pensées detaches sur la peinture – a series of stabs at description, full of crossings-out and redundancies, a bit like the Cubist grids I am trying to find words for. This disconnected quality seems necessary to me, precisely because it is the opposite quality that I most distrust in the accounts of Picasso’s painting we already have: that is, the way they are driven by a basic commitment to narrative continuity, by a wish to see Picasso’s work from 1907 to 1912 as possessing a logic or forming a sequence, as not being broken or interrupted in any important way [emphasis added]. [33]

Clark even refers to the individual components – the geometric shards and shivering grids – comprising Picasso’s The Architect’s Table and Man with a Pipe as “episodes of likeness.”[34] By lifting the word “episode” from its conventional denotative context (where it is primarily used as a temporal unit) and situating it in the realms of the graphic, the physical, the material, and the spatial, Clark points toward modes of critical re-signification necessary in positing Cubism as a representational idiom within cinematic narrativity.

Toward a Narrative Cubism: Iteration, Contradiction, and the Relativity of Truth

Before grappling with the idea of cubist narration, we might recall that Cubism, as a set of shared ideas circulating within the spheres of European painting, sculpture, and poetry teetering on the cusp of the Machine Age, came to be perceived as a pivotal moment in the burgeoning Modernist enterprise to strip away the calcified traditions of the previous century’s social order. More importantly, Cubism had the specific effect of shattering the four hundred year-old conventions of a perspectival system that, since the early years of the Florentine Renaissance, was bound to a fixed, unitary line of vision emanating from a single viewing subject. Not long after Georges Braque’s bizarreries cubiques aroused in Henri Matisse and his fellow Fauvists the not-altogether-complimentary exclamation “Toujours les cubes!,” what began in 1908 as simply a new approach to form and figural representation led to radical attempts to reproduce the world as a conceptual totality through fragments.[35] The Cubist image, in its earliest Post-Impressionist guises, and then into its analytic and synthetic phases, attained its purest expression in the paintings of Braque and Picasso, artists who exploded pictorial space into intersecting lozenges shuffled so as to render an object from multiple perspectives. As a result, each painting provided a composite image, a multitude of sensations made simultaneous and sometimes contradictory.

During the early decades of the twentieth century, there was already a general recognition of Cubism’s legacy, and a growing appreciation of the cross-fertilization among multi-perspectival systems in poetry, painting, and cinema.[36] Writing on the “Synchronization of Senses,” Sergei Eisenstein even recognized a pre-Cubist multi-perspectival tendency in the swirling compositions of El Greco, a Mannerist artist of the late-sixteenth century whom Eisenstein dubbed the “forerunner of the newsreel” and one of “the forefathers of film montage.” In El Greco’s View and Plan of Toledo (1604-14), for example, “realistic proportions have been altered, and while part of the city is shown from one direction, one detail of it is shown from exactly the opposite direction!” This, Eisenstein argues, “provides an instance for us of an artist’s viewpoint leaping furiously back and forth, fixing on the same canvas details of a city seen not only from various points outside the city, but even from various streets, alleys, and squares!”[37]

Now recognized as “the first genuine avant-garde film produced in the United States,” Paul Strand’s and Charles Sheeler’s seven-minute New York city-symphony, Manhatta (1921), is also one of the earliest (if most miniature) manifestations of cubist cinema, its heterogeneous dispersion of street-scenes “deconstructing renaissance perspective in favor of multiple, reflexive points of view.”[38] Not unlike longer, feature-length episode films, Manhatta, according to Jan-Christopher Horak, “ultimately seems to construct numerous, often conflicting texts, oscillating between modernism and a Whitmanesque romanticism, between fragmentation and narrative closure. As a result, the subject is positioned in the oblique perspectives of the modern skyscraper, but is simultaneously asked to view technology as an event ideally in tune with the natural environment.”[39]

This final part of my essay examines what I call “cubist narration,” which refers to any film in which a kernel story as seen from various characters’ perspectives is replayed in parallel or obliquely angled episodic form.[40] It can also be referred to as “iterative narration,” for it involves a story or set of events being enacted two or more times, in serial succession, only to end in inevitable ambiguity. Such generically diverse films as Rashomon, Les girls (1957), The Man who Shot Liberty Valance, Cold Days (Hideg napok, 1966), Four Times that Night (1972), He said, she said (1991), Pulp Fiction (1994), I Shot a Man in Vegas (1995), Courage under Fire(1996), The Falling (1998), Hilary and Jackie (1998), Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Hero, and 11:14(2003) are perhaps the cinematic equivalents of novels containing multiple internal focalizations (such as Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone [1868]) – films that highlight the biases and limitations of human perception. Like the forked-path narratives mentioned above, they offer a series of alternate realities and parallel lives. However, in foregrounding a heteroglossia of competing, sometimes oxymoronic, discourses, these films problematize the nature of “truth,” which in most cases is relative and linked to subjective experience.

The most exemplary and influential case of cubist narration in film history is Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon. The film, broken into seven different accounts of a single murder, replays this pivotal event through various characters’ eyes, each time casting doubt on the previous version. First a woodcutter tells the tale; then a priest; then a policeman; then Tajomaru, the bandit who admits that he attacked the samurai and raped his wife; then the wife herself, who claims that she knifed her husband following the rape because of his scornful expression; then the spirit of the dead samurai, who speaks through a medium and claims that he committed suicide because of his wife’s preference for the bandit. These accounts, delivered to an unseen judge occupying the position of the camera, are further complicated by the woodcutter, who makes amendments to his own story and says that after the rape he witnessed a different set of circumstances.

Many critics believe that this last diegetic observer, the woodcutter (who also benevolently rescues and adopts a baby, his seventh to be exact), has no reason to lie and effectively nullifies the preceding episodes’ legitimacy; yet he too appears to be playing loose with the truth. This is emphasized when another commoner shouts at him, “Look, you may have fooled the police, but you don’t fool me…Where is that valuable dagger that was pulled out of the samurai’s body?” In each case, it seems, there is a distortion of reality based on selfish motives. There would appear to be a correlation, then, between this text which continually undercuts itself and the kind of self-denying discourse that Susan Stewart describes in her book Nonsense: Aspects of Intertextuality in Folklore and Literature. As Stewart points out, certain novels like Samuel Beckett’s Molloy(1955) systematically cancel themselves out every step of the way.[41] However, not unlike the six men of Indostan in poet John Godfrey Saxe’s “The Blind Men and the Elephant” (who each experience the physical presence of a pachyderm in radically different ways: “very like a spear,” “very like a fan,” etc.), the six characters in Rashomon personify the phenomenal constraints each of us face in coming to terms with life’s antinomies. Only by “changing one perspective for another,” as Robert van Es states in his concise reading of Rashomon, do “we have the opportunity to learn something, to acquire new insights.” [42]

Just as questions about the “right” point of view have been circulating in philosophical discourse since the days of Blaise Pascal, so too have Rashomon‘s multiple and contradictory narratives continued to open new channels for discussing the ways in which cinematic fictions are habitually taken as representations of reality. Since this film has already been examined in detail by numerous scholars (whose own divergent interpretations replicate its internal fragmentation of perspective), I see no need to pursue Kurosawa’s shrewd use of relativism and irony any further; except to say that few of the films, television episodes,[43] and novels [44] spawned from this Japanese classic have provided as many alternate points of view. And, as a result, few are as profoundly unsettling in depicting epistemological ambiguity.[45]

Rashomon was by no means the first film to feature contradictory flashbacks and mendacious or multi-perspectival narration – elements that are found in a handful of expressionistic films noir and existentialist social problem dramas of the 1940s, such as Edward Dmytryk’s Crossfire (1947). Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane(1941), of course, is famous for just such an approach, as is another “anecdotal portraiture” released in 1941, Julien Duvivier’s Lydia. This loose Hollywood adaptation of the same director’s episodic French-language film Dance Card (Un carnet du bal, 1937) gave actress Merle Oberon the opportunity to go through thirty-two changes of costume while playing off four romantic leads, three of whom gather together in the waning years of their lives to reflect upon their shared object of affection. These former beaux’ individual accounts of the main character are rendered serially as sentimental flashbacks and are the basis for visual and aural inconsistencies.[46] For example, when Lydia, now a spinster, recounts the ball she attended as a young Boston debutante, it is depicted as an enormous and glittering space filled with swelling music, and her entrance is filmed in exquisite slow-motion to convey her feeling of entering into a “dream.” However, when Joseph Cotton’s character – the more down-to-earth Michael – tells his version of the event, the dance is considerably smaller in size.

This presumably less embellished description, which Jeanine Basinger argues is a “masculine, more realistic presentation” with “no mirrored walls…one harpist…and a single violinist,” would appear to be Duvivier’s way of undercutting and deglamorizing phantasmic elements associated with the genre of the woman’s film.[47] However, such a reading skips over the possibility that there is more than one truth being presented here; that there are – as Linda Hutcheon argues in her discussion of postmodern novels such as Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot (1984) and John Fowles’s A Maggot (1985) – “only truths in the plural.”[48] Plus, this gendered rupture of perspective also resonates with the larger issue of multiplicity, something articulated at the end when Michael says, “I kept thinking as I was listening to all the stories: What was the real Lydia? Which one? Which One?,” to which the old woman responds “The ‘real’ Lydia? Dear me…there was no real Lydia, Michael. There were dozens of them.” [49]

If postmodern art is “doubled and contradictory,” as Hutcheon argues, then films as diverse as George Cukor’s Les girls (“the Rashomon of MGM musicals”) and Anand Tucker’s Hilary and Jackie (a dual biography of celebrated British cellist Jacqueline Du Pré and her less famous sister) would seem to fit into that category, despite all outward appearances. The former film, a frothy “offstage” musical set in London’s Royal Court of Justice, is notable not only for being Gene Kelly’s last job under contract with MGM, but also for parodying such contemporaneous productions as The Wild One (1954) and nostalgically consolidating tropes and images associated with the hoofer’s earlier films (in particular Singin’ in the Rain [1951]). More importantly, this unusual film, which dares to thematize suicide, finds numerous opportunities throughout its multiple flashbacks (each told from a different person’s point of view) to self-reflexively comment on the questionable nature of truth and the fabricated act of cinematic signification, something that supposedly only “serious” works of art do.

Hilary and Jackie, based on the controversial book A Genius in the Family, is no less adept at making perspectival pivots around a serious subject (Jacqueline du Pré’s battle with multiple sclerosis in her thirties) whose gravitational pull is as strong as the rivalry between the titular sisters. Publicly derided by friends of the dead musician as well as by many film critics,[50] this warts-and-all portrait of a sibling love-hate relationship is marked by ambiguity and doubleness, taking us into the mind of Hilary before flashing back (at the forty-five minute mark) to many of the same events witnessed earlier, only this time from Jackie’s point of view. Unlike other bivalve portmanteau films (individual works consisting of exactly two stories or variations on a theme), such as the Hollywood productions Face to Face (1952), Actors and Sin (1952), and Movie Movie (1978), as well as European productions like Of Love and Lust (Giftas, 1960), The Couples (Le coppie, 1970) and His and Her(a.k.a. This and That; Questo e quello, 1983), whose titles alone indicate their doubleness, Hilary and Jackie offers two different yet mirroring versions of the same story. Its point/counterpoint musical structure is indicative of a type of reiterative narration wherein episodes collectively render an event more fully while compounding the difficulties involved in reaching a non-ambiguous and permanent resolution.

The 1952 Sid Kuller Productions release Actors and Sin makes for an interesting comparison due to its dialogic dimensions. The title, a truncated composite of two forty-minute short films written by Ben Hecht (“Actor’s Blood” and “Woman of Sin”), suggests a perfectly rational blending of thematic elements. Indeed the first episode, set within the world of theater, hinges on the actions of a young female actress, Marcia Tillayou, who ascends the heights of her profession yet sinks deeper into moral depravity until she is found by her overprotective father with two bullets in her chest. Significantly, “Actor’s Blood” is itself split in half, the first part being an extended flashback detailing Marcia’s rise to fame on Broadway and her eventual murder, the second half moving forward and tracing father Maurice’s attempts to crack the case. Culminating with a conventional reveal scene familiar to fans of detective fiction, one in which nearly a dozen suspects are invited to dinner where the murderer will be revealed, this episode nevertheless suggests the ambiguity of Rashomon in its treatment of subjective experience and perceptual limitations. “Lies, lies! They’re destroying my daughter with lies,” Maurice moans just before her death (the result, we later learn, of suicide); his nepotism clearly clouding his ability to see Marcia as she “really” is: an unfaithful and malicious woman.

Moreover, the entire episode overflows with binaristic imagery and talk. For instance, two cockatiels in Marcia’s dressing room repeat her and her husband’s words, reminding us that the latter – a screenwriter named Alfred O’Shea – supplies his wife’s words onstage. As the narrator of this story, Alfred later says in voiceover, “Our marriage was ideal, and then our marriage was a bust. She began driving me potty with her infidelities. She was in love, out of love, half-Isolde, half-pirate.” This flip-flopping between extremes not only plainly conveys their inability to see eye-to-eye, but also draws our attention to the overarching duality of this most curious episode film, which switches from a tragic story of suicide set in the East Coast world of theater (“Actor’s Blood”) to a comedic riff on children’s creativity set in the West Coast world of Hollywood (“Woman of Sin”).

By nature, episode films in general not only accommodate dissonant visual and aural styles, but also allow audiences to reappraise what has already transpired, weigh the evidence given in each segment, and make qualitative decisions drawing on their own selective memories. As an ailing Jackie complains to husband Daniel Barenboim in the abovementioned biopic, “At least Hilary chose her life.” Like the cellist’s sister, spectators have the opportunity to choose which episode they find most aesthetically stimulating, psychologically compelling or “true” – an episode in which to believe or put one’s trust.

If the reception of anthology, omnibus, portmanteau, and sketch films rests on audiences’ willingness to “take sides,” to pick and choose the best of the bits, then the specter of non-consensus surely suggests political and ideological dimensions, something taken up in a few works; most notably the Macedonian-French-British co-production Before the Rain (Pred dozhdot, 1994), director Milcho Manchevski’s award-winning debut feature about ethnic and racial disharmony in which each of its three parts, “thanks to Möbius strip chronology and recurring images, cancels out the other two.” [51] The three episodes comprising this “border-crossing” film (“Words,” “Faces,” “Pictures”) revolve around individuals and communities inside and outside the volatile Balkan region taking sides during a time of political unrest. Significantly, each of the episodes is noticeably steeped in circle imagery. This lends the entire collection of overlapping yet contradictory stories about Muslims and Orthodox Christians, Albanians and Macedonians a cyclical dimension despite an old priest’s enigmatic words (spoken at the beginning and repeated throughout Before the Rain): “Time never dies….The circle is not round.” [52]

This contradictory notion is inversely reminiscent of words spoken at the beginning of Run Lola Run:

“The ball is round, the game lasts ninety minutes.” That line, delivered by a security guard to the camera just before he kicks a soccer ball into the sky, concludes with the statement, “Everything else is pure theory.” The ball, which then hurtles back to earth and lands inside the “O” in “Lola” that has been formed by a multitude of bodies, is indeed round. However, “pure theory” can take an infinite number of shapes, and – like “everything else” (the “details” that often go unnoticed in the game of life) – helps us to conceive of alternate futures and contradictory pasts if paradoxically attuned to the existential demands of the present. Similarly, so too does episodic writing (or what I call “critical episodicity”) aid in our discovery and recovery of the narrative possibilities latent within cinematic texts that – like life – are contradictory in their combined fragmentation and integration, not to mention their simultaneous engagement with physical and metaphysical planes of existence.

Just as the writer and director of Blind Chance, Krzysztof Kieslowski, could be said to practice a kind of “metaphysical realism” in his films (displaying a commitment to social reality, material solidity, and documentary verisimilitude that nevertheless intersects with an equally vested interest in the spiritual plane’s speculative immaterialism and contingency), so too do Milcho Manchevski, Ventura Pons, Alejandro González Iñárritu, Hong Sang-soo, and numerous other contemporary filmmakers from around the world exude an equally paradoxical sense of wonderment in the mundane and the extraordinary in their works. Their complex, multi-perspectival, forking-path and cubist films are not merely formal exercises in empty episodicity, however. Quite the opposite, they, like Kieslowski’s Blind Chance, deploy their internal segmentation allegorically, as a way of illuminating the psychical demands of living in politically fragmented and socially contested spaces. Time will only tell if future artists and commercial filmmakers take up Borges’s challenge to expand the narrative possibilities of cinema even further.

Endnotes

[1] Because the word “if,” a conjunction denoting “in the event that” or “on the condition that,” immediately brings to mind the possibility of numerous possibilities, it gestures toward the multiplicity of episode films in general; hence its frequent appearance in the titles of such anthology and omnibus productions as If I had a million (1932), If you love me (Aisureba koso, 1955), If these walls could talk (1996), and If you were me(Yosotgae ui sison, 2003).

[2] Consider, for instance, the French OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a metafiction group whose members included authors Georges Perec and Raymond Queneau.

[3] Jorge Luís Borges, “The garden of the forking paths,” Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Viking Penguin, 1998), 122.

[4] Borges, 124.

[5] Dead of Night was also prefigured by a much earlier flashback-filled British film, Friday the Thirteenth(1933). This Gainsborough production directed by Victor Saville features a Grand Gotel-style gathering of the studio’s top stars, several of whom take center stage in suspenseful vignettes connected by a London bus crash.

[6] The double motif personified by the antagonistic Dr. von Straaten and Walter Craig in Dead of Night‘s frame story spreads throughout each of the five embedded tales (directed by Alberto Cavalcanti, Charles Crichton, Basil Dearden, and Robert Hamer), with characters therein finding themselves reflected by doppelgangers of sorts.

[7] Borges, 125.

[8] Lev Manovich’s insights into database structures and algorithmic formulas are worth mentioning here, not only because they clarify the syntagmatic and paradigmatic dimensions of computerized collections, but also because they point toward ways in which the interactive narrative, or “hyper-narrative,” of new media forms can be likened to forking-path films that offer multiple trajectories through a simulative set of situations. See Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

[9] In using the expression “what could be; would be; or might have been,” I am borrowing Mark J. P. Wolf’s words from the introduction of his article, “Subjunctive documentary: computer imaging and simulation,” in Jane M. Gaines and Michael Renov, eds., Collecting Visible Evidence (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press), 274.

[10] In 1997, Ventura Pons, a frequent dabbler in the episodic format, adapted a La ronde-like play by Sergi Belbel into a film called Caresses (Carícies). Broken into eleven interlocking episodes, this low-budget production kicked off a fragmenting trend in Spanish filmmaking, one reflected in the forking-path narratives The Lovers of the Arctic Circle (Los amantes del circulo polar, 1998) and Twice Upon a Yesterday (1998).

[11] Although completed in 1982, the feature was officially banned, and not until 1987 did it get a theatrical release. This was due to the national clampdown on all potentially subversive cultural productions. Not long after martial law was declared throughout Poland in December 1981, it began crippling the nation’s film industry, making it difficult for artists like Kieslowski to gain access to film stock and equipment.

[12] Borges, 121.

[13] David Bordwell, “Film futures,” SubStance, Vol. 31, no. 1 (2002): 88-104.

[14] The dialectics of repetition and disjuncture so intrinsic to the episodic, forking path form should not be overlooked. Indeed, several anthology, omnibus, portmanteau, and sketch films play with the idea that in similarities lay the seeds of difference, and vice versa. For instance, in the opening scene of Love Stories(Historie milosne, 1997), a more recent multi-story Polish film dedicated to Kryysztof Kieslowski and directed by the star of his 1994 black comedy White (Blanc), Jerzy Stuhr, four different characters – a college instructor, a priest, an Army Lieutenant, and a captured drug-smuggler – arrive one after the other at a psychiatric clinic. While in and of itself this three-minute scene might seem unremarkable, the fact that each of the four protagonists is played by Stuhr – his clothing and comportment being the only initial signifiers of individuality – not only prepares the audience for the motivic emphasis on the number four throughout the film (the number of years the convict spent in prison; the number of questions asked of the priest at one point; an important date: December 4th; etc.), but also suggests that what the film has to say about interpersonal relationships cannot be divorced from its commentary on social and cultural schisms, rendered through a repetitive foregrounding of difference at semantic and syntactic, textual and extratextual, levels.

[15] Krzysztof Kieslowski, Kieslowski on Kieslowski, ed. Danusia Stok (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1993), 113.

[16] Kieslowski, 113.

[17] This use of the word “game” in Run Lola Run gestures toward the framing device in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, in which various tellers “compete” against one another for the reader/listener’s ear.

[18] Tom Whalen, “Run Lola Run,” Film Quarterly, Vol. 53, no. 3 (2000): 33-40.

[19] Jamie Skye Bianco, “Techno-cinema,” Comparative Literature Studies, Vol. 43, no. 3 (2004): 379.

[20] Slavoj Zizek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieslowski between Theory and Post-Theory (London: British Film Institute, 2001), 81.

[21] Zizek, 151-152.

[22] Zizek, 152.

[23] Zizek, 172.

[24] Zizek, 125-126.

[25] Zizek, 88-89. Janet Bergstrom, in her Introduction to the edited volume Endless Night: Cinema and Psychoanalysis (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), marvels at Zizek’s associative powers, his stream-of-conscious command over seemingly incompatible material. Bergstrom characterizes the so-called “Zizek-effect” as “a dizzying array of figures and cyber references” to

J.G. Ballard, Plato, Lacan, Hegel, Schelling, Marx, Saki, Stargate, Welles, Kafka, the Lascaux cave paintings, Virtual Reality (VR), Slovenia’s Cerknica lake as magic screen, Slovene author Janez Valvasor,Terminator 2, Indiana Jones, Deleuze, film noir and the femme fatale, Foucault, Chaplin, pensée sauvage, Eisenstein’s project to film Capital, Sherry Turkle, Heidegger, Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channels, Multiple User Domains (MUD), Allucquere Rosanne Stone, the Robocop, Judith Butler, John Searle’s Chinese Room argument, artificial intelligence (AI), Kant, Marcuse, Freud, Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD), Malebranche as the philosopher of VR, Napoleon, Descartes, God, Aristotle, an Aztec priest, Schreber, Fredric Jameson, “Deep Ecology,” Stalin, Othello, de Gaulle, Dostoyevsky and Habermas. (8-9)

[26] Peter Wollen, “Rope: three hypotheses,” Alfred Hitchcock: Centenary Essays, ed. Richard Allen and S. Ishii-Gonzalès (London: British Film Institute, 1999), 78, 81.

[27] Susan Sontag, “Godard’s Vivre sa vie,” Against Interpretation (New York: Anchor Books, 1990), 199.

[28] Sontag, 199.

[29] Robert Ray, The Avant-Garde finds Andy Hardy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995). Another good source of critical episodicity incorporating structural devices that the Surrealists would be proud of, is Rashna Wadia, “So many fragments, so many beginnings, so many pleasures: the neglected detail(s) in film theory,” Criticism 45.2 (2003): 251-278.

[30] Mark Betz, “Film history, film genre, and their discontents: the case of the omnibus film,” The Moving Image: Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists no. 2 (fall 2001): 56-87.