Cine-Tracts: A journal of film and cultural studies #5, vol. 2, no. 1, Fall, 1978, pp. 42-62.

Ronald Abramson (email: ronabrams@earthlink.net) and Richard Thompson

From the beginning, Screening The Past was committed to publishing a section called Classics and Re-runs. The purpose of this section was to call attention to screen historical articles of interest which had become difficult to access, or were no longer available. We have always valued this part of the journal, and are pleased to reactivate it in our tenth anniversary issue.

The article I selected to feature in this issue was co-written by one of our editors. It is an article that I had used when I decided to teach Young Mr. Lincoln in a subject called Single Film Research. I chose to teach Young Mr. Lincoln for two reasons. First, my students had told me, on different occasions, that the films of John Ford were a glaring absence in their film history knowledge. They knew of John Ford but they had never seen a Ford film. I also thought that this might be an opportunity to introduce them to the famous Cahiers study of this film, and some of the contemporaneous responses to the study. Thompson related to me how the article came about:

Ron and I were doctoral students in the Critical Studies program of UCLA’s film school c. 1975-1977. We had spent the 1960s seeing all the films we could and dealing with that decade’s paradigm shift: auteurism, learning how to read Andrew Sarris, yellow-front Cahiers, Positif, Film Culture, and Movie. The 1970s were the theory decade: we learned to read post-May 1968 Cahiers, Sam Rohdie’s Screen, Peter Wollen, Christian Metz, and a wealth of new film journals in English, many of which debuted in the remarkable year 1976.

In UCLA’s system, doctoral students did two years of classroom seminars; then a five-day field exam; then finally advanced to candidacy to begin work on a dissertation. During the seminar years, we had visiting professors. In our years, they were Dudley Andrew and Brian Henderson, who taught seminars on criticism and theory; “Young Mr. Lincoln Reconsidered” began in those seminars at a time when the Cahiers collectif piece was positioned as an essential and exemplary (read: unavoidable) film studies text.

Ron and I were sceptical about several aspects of the Cahiers piece, its method, and its adequacy in reading the John Ford film (also a central item at the time – we all knew the film quite well). We thought this imperial text might be under-dressed and ripe for a critique. In the temper of the times, we also took it as given that an effective critique would have to be pitched on the same theoretical ground as the original article.

So we wrote and rewrote the piece, finally taking advice on whether we we should try to get it published. Our advisors said, nice essay, but nobody’s interested in publishing articles on the Cahiers piece. In the next year, at least five articles appeared on the Cahiers piece in Anglophone film journals. So we joined the queue.

I did not share Abramson and Thompson’s experience of the importance of the Cahiers piece, and I did not participate in the culture that regarded it so highly. It was something that I came to later, when I was piecing together the important moments in film writing. What I discovered in the Cahiers piece is an artefact of a screen culture moment; it encapsulates a certain mind-set, a way of thinking and a language typical of mid-1970s. What particularly interested me about the Abramson and Thompson response to the Cahiers piece was not only its insightful critique but also the example it provides of the healthy debate that was part of a lively film culture at the time.

When I decided to use the Abramson and Thompson piece in my class I found out that it was difficult to access because very few libraries had back copies of the journal, Cine-Tracts. This lack of availability and my students’ very positive response to the article, made the decision to republish it an easy one. The unforeseen bonus: the release this year of the Criterion Collection’s fine Young Mr. Lincoln DVD.

Anna Dzenis

Young Mr. Lincoln Reconsidered: An Essay on the Theory and Practice of Film Criticism

by Ronald Abramson and Richard Thompson

The collective text on Young Mr. Lincoln by the editors of Cahiers du cinéma (no. 223, 1970; translated in Screen, vol. 13, no. 3, Autumn, 1972) marked the beginning of a new period in film theory and criticism. Its influence among serious film critics hardly needs citation: the text has drawn commentaries from Ben Brewster, Brian Henderson, Bill Nichols, and Peter Wollen. It announces itself as a radically different kind of criticism from that which has gone before.

Perhaps this difference is best brought out when Henderson compares the Cahiers text with Wollen’s afterword:

Wollen’s reading (is not even) an interpretation, a translation of what is supposed to be already in the film, into a critical or meta-language. There are as many readings of a text as there are systems of interpretations; what is important here is that the reading be rigorous, that it employ only one critical system and proceed towards comprehensive translation of the film into its meta-language. Wollen’s afterword contains bits and pieces of such translations, but none of these is sustained or developed towards its logical conclusions…What is most important in the Cahiers piece is its method of reading, its means of producing results. Wollen mystifies his own reading by simply adducing a list of findings without presentation and questioning of the method which generated them. (Henderson, preliminary draft, Young Mr. Lincoln study, UCLA, 1974.)

This is what seems important to us about the Cahiers piece: it is rigorous – that is, it presents us with its method and sustains that method throughout the reading; it sets explicit limits on the kinds of critical systems it employs; and it comprehensively translates the elements of the film into its meta-language.

The tendency in film criticism which this piece helps to establish is this: from now on a piece of film criticism may be interrogated at two levels. The specific reading of the film may be questioned in the terms of the meta-language the critical system employs; and the critical system itself may be questioned. The strength of the new criticism is that it refuses facile or convenient judgements and/or interpretations. In short, it is anti-eclectic. Within clear, self-imposed limits this criticism tries to be rigorous and comprehensive, testing its critical system against every element in the film. It attempts to present knowledge-in-the-process-of-formation, a systematic working-through of a text which demonstrates how a knowledge product (an understanding) is produced. This is quite different from the simple presentation of the end products of this work-process – if indeed there has been any systematic work done at all.

The Cahiers piece in some ways fails to live up to its own ideal: it does not concretely specify through allusions to the mise en scene how and why certain abstract categories of the meta-language are to be invoked. The categories (Man, Woman, Law, Nature) are simply imposed on the film. Furthermore, the relations between categories are presumed to be pre-determined – by reference to certain Marxist notions of how ‘bourgeois ideology’ functions. These relationships are never adequately tested against the structure of the film. (This second point is crucial in our own discussion since we accept most of the categories of Cahiers’ meta-language but we do not accept the asserted relationships between categories. We leave open the question of the functioning of ‘bourgeois ideology’, studying the film in detail in order to learn how textual meanings are produced.)

Our effort, as metacriticism, questions the Cahiers presentation at two distinct levels: first, as it re-interrogates the film-text in the terms of the meta-language of Cahiers’ critical systems – Marxism (Althusser) and Freudianism (Lacan); second, as it interrogates those critical systems themselves. [1] Furthermore, we will demonstrate that Cahiers’ “mis” reading of the film is inextricably linked to the critical system which determines their reading. Our effort is not meta-criticism as a simple commentary on the Cahiers article; we will take up the challenge implicit in the Cahiers presentation that faces any critic who addresses the whole of that presentation rather than any particular aspect of it. That is, we will re-read the film as rigorously and comprehensively as Cahiers, and our differences (and the reasons for those differences) will be made clear through direct references to the text.

1.

The Screen introduction to the Cahiers article noted that the Cahiers critique of Young Mr. Lincoln was rooted in earlier theoretical work that had been published prior to that article.

In the Cahiers editorial “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism” (Screen, vol. 12, no. 1), Ford films were placed … in a category of “films which seem at first sight to belong firmly within the ideology and to be completely under its sway, but which turn out to be so only in an ambiguous manner.”

The Cahiers text on Young Mr. Lincoln … is a concrete extended analysis of a film within this category. The Cahiers writers describe a disjuncture in the film between its formal signifiers … and the ideology which these are intended to project… (Editorial, Screen, vol. 13, no. 3, Autumn, 1972, p. 2.)

In this section we are not concerned with the contradiction between the ideological project and its formal presentation but rather with the definition of the ideological project itself.

The ideology of Ford’s film which the Cahiers writers describe variously as “the Apology of the Word” (natural law and the truth of nature inscribed in Blackstone’s Commentaries and The Farmer’s Almanac), the valorisation of the complex Law/Nature/Woman…(Screen editorial, p. 2.)

For Cahiers, this ideological project is assumed to be the naturalization of the bourgeois law. What we will show in the following analysis is that the relation of the film to such an ideological project is highly problematical; that the triadic equivalency used to validate Cahiers’ propositions on the ideological stance of the film cannot be substantiated by a close reading – active or not – of the film.. Furthermore we will show that this (mis) reading is not a mistake but rather is bound up with their own ideological stance which suppresses certain meanings while valorizing others. Their theories and the method used to validate them are circular; i.e.,Cahiers’ assumptions about ‘bourgeois ideology’ in this film are never tested against the film’s system of signification. The ideological project of the film is simply assumed by Cahiers to be a function of ‘bourgeois ideology’ in general.[2]

The cornerstones of Cahiers’ reading of Young Mr. Lincoln are: the establishment of a triadic equivalency – Nature/Law/Woman; and then the misreading of this equivalency as the naturalization of bourgeois law, or property rights, and the supreme rule of capital.

The third sequence of the film is the one used by Cahiers to assert the triadic equivalency.

Centered on Lincoln, the scene presents the relationship Law-Woman-Nature which will be articulated according to a system of complementarity and of substitution-replacement. It is in Nature that Lincoln communes with Law: it is at the moment of this communion that he meets Woman: the relationship Lincoln-Woman replaces the relationship Lincoln-Law since Woman simultaneously interrupts Lincoln’s reading of the book by her arrival and marks her appreciation of Lincoln’s knowledge and encourages him in his vocation as a man of knowledge and Law. (Screen 13:3, Cahiers collectif.)

If we read this passage closely we see immediately that there is a problem: while it is true that “It is in Nature that Lincoln communes with Law”, it is also true that Woman interrupts this communion. Any convenient triadic equivalency is thus thrown into question. Furthermore, it is possible to read Ann’s encouragement of Lincoln to pursue the Law as a sign of her immaturity, her flirtation with Power, as it will be with Mary Todd later on – Mary becomes a sign of the power struggle between Lincoln and Douglas (neither Mary or Ann exist under the sign of Motherhood). It is important to remember that Lincoln does not try to engage Ann in any discussion of the Law; he quickly closes the lawbook and puts it aside. The interruption of the communion of Law and Nature – a communion physically mediated by Lincoln, as he brings the book into the woods and uses it there – is the most significant moment of the scene: Ann Rutledge’s offscreen voice surprises and interrupts us, the viewers, as well as Lincoln. It is clear from Lincoln’s actions that he regards Ann as someone not be involved with or identified with the Law. (the scene has overtones of a marriage ceremony: the framing of Lincoln and Ann under an archway created by the branches of the trees and a low angle shot – the only one of its kind in the scene, with Lincoln saying “I do” with music the background emphasizing the solemnity of the occasion.) There is certainly no equivalency of Woman with Law. What there is, is difference.

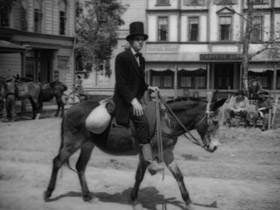

Interruption of Lincoln’s communion with Law

Lincoln saying “I do” to Ann by the river

In the very next scene – Lincoln at Ann’s grave – this difference is elaborated into a full-blown opposition, thus placing the figure of Lincoln in opposition to Woman and Nature. This opposition is precisely what must be overcome, and it can only be overcome by placing both elements of the opposition under the sign of a higher order: The Family. The discourse of Lincoln throughout much of the film will be of the either/or type (right/wrong), while throughout the film the Mother’s (Mrs. Clay’s) discourse will be of the both/and type, and so placed in opposition to his. Let us designate her discourse as The Law of the Family and Lincoln’s as The Law of the Social Order and the State. Cahiers presents the movement of the film as a simple elaboration of astatic triadic equivalency in which the Law of Nature and the Law of Society are never in contradiction. We on the other hand see this as a dialectical process which includes the overcoming of opposition; the transcendence of either/or thinking (binarism) as a limiting attitude; and the education of Lincoln to the fact that this Law must serve a higher Law, namely the Law of the Family. Only then is the Law and the violence of the inscription of the Law justified. And only then will Lincoln be able to assume his place as the Unifier of the Nation (the greater family).

The movement of the film is the gradual subordination of the Law to the Law of the Family. Since the Rule of Law is the Rule of Capital (property rights equals rights; and violations of those rights equals wrongs), and since this Rule of Law is shown to be subordinate in the film, then the relationship of the ideological project of the film to ‘bourgeois ideology’ becomes complex and mediated rather than direct and causal.[3] One can see here, if one chooses, the simple justification of the Rule of Law/Capital under the sign of a Higher Law and the Law of the Family. However, a less simplistic reading will also see the breaks and gaps in which contradictions may reside. After all, capitalism, especially in its advanced stag, is destructive of family relationships; therefore, appeals to a Higher Law can be an encumbrance to the prerogatives of monopoly capital (as in much of the resistance to the Vietnam war, or environmentalist opposition to oil exploration); and what Cahiers sees as a repression of politics could just as easily be understood as a critique of politics.[4]

The Law is subordinated in the film to the Law of the Family. One can go two ways in establishing the specific dynamics of such a relationship. The Law can be justified by the Law of the Family, or it can be critiqued (and perhaps trivialized) by the Law of the Family. Cahiers reads the film in light of the former and sees the relationship of the Law and the Law of the Family in the film as one of substitution-replacement. Here the Cahiers ideological project is revealed: to reduce everything and every relationship to the Law of Capital, to reduce any opposition to the Law of Capital to the “idealist mask” of “spirituality” which conceals the true “materialist” relations of Capital; and, where that opposition to the Law of Capital resists such a reductive reading – as in Young Mr. Lincoln, where it is obvious from the courtroom scene that the Law is being criticized and trivialized – then the opposition is being repressed in the analysis.[5]

This universalization of Marxist critical concepts under the signs of “science” and “materialism” and within a code of (bourgeois?) political economy is such a crucial moment of the Cahiers critical stance that it will be necessary to deconstruct it again and again. For the moment, we will be content to show how this discourse misreads the film, represses certain elements of the film, and flattens out critical contradictions within the film.

Lincoln, immediately after Ann’s death

A close reading of the film presents certain anomalies in the Cahiers interpretation, not only in the scene by the river which they use to establish the triadic equivalency, Nature/Law/Woman, but in other scenes as well. For instance in the next scene, in which Lincoln visits Ann Rutledge’s grave and has to decide whether to stay in the country settlement or go to Springfield to pursue a law career, Cahiers interprets Lincoln’s words, “Well, Ann, you win. It’s the Law” to mean that “Lincoln’s definite acceptance of the Law is thus, once again, made under Woman’s direct influence”.

What Cahiers fails to remember in its analysis is that Ann Rutledge is dead! That is to say, Lincoln’s choice of Law is occasioned under the sign of Ann’s death. The fact that in the next scene we see Lincoln riding into Springfield in the all-black, funereal outfit only serves to underscore the relationship between Death and the Law in the film and to undermine Cahiers’ interpretation of these events as establishing a Nature/Law/Woman equivalence.

What the Cahiers reading does is blur over crucial differences and flatten out contradictions – the difference between Ann alive and Ann dead finds no place in the Cahiers analysis. In fact, their whole analysis is a repression of the fact of death in the film. In Lincoln’s meetings with the Clay family he continually asserts that Mrs. Clay is like his (dead) mother, that Sarah reminds him of his (dead) sister of the same name, and that Carrie Sue is like (dead) Ann Rutledge. This is part of Lincoln’s effort to “come alive”, to enter into the Family as husband/son and to subordinate his death-like Law to a life-like Law (the Law of the Family).

The notion of Lincoln wishing to “come alive”, to go back to the time before Ann’s death when he was emotionally alive and close to his roots both in nature and in the community, suggests that Lincoln seeks to avert death at two levels: first, he seeks to avert his emotional death which commences with Ann’s death but includes being “uprooted” like the dead branch that falls toward the Law and the City (Springfield). Further, he seeks to avert the inevitability of his physical death, for he knows that to continue toward his destiny is to be assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. (This is highlighted in a scene cut from the release version which shows Lincoln entering Springfield and passing a theatre with a sign announcing “Booth in Hamlet”.

Lincoln’s introduction: Lincoln Reclining

But who is the Lincoln who seeks to avoid his destiny? Who is the Lincoln who “knows”? This line of reasoning points to the fact that there are actually two Lincolns in the film. There is the Lincoln who is the historical figure/myth, and there is the Lincoln who acts this historical Lincoln. (This fact of the text is partially hidden by the fact that Henry Fonda plays “both” roles.) When we are first introduced to Lincoln he is like an actor preparing to play a part (for this we are indebted to Janey Place’s Young Mr. Lincoln study which occurs in the current issue of Wide Angle). All of his movements suggest an actor preparing to go onstage ? in this case the stage of American history. Call this first Lincoln, Lincoln-R, i.e. Lincoln Reclining; call the second Lincoln, the historical figure/myth in the film, Lincoln-S, i.e. Lincoln Standing (it is clear that in this very splitting, the film seems to “re-write” the Lincoln myth).

The point is that Lincoln-R is a reluctant Lincoln. (This is the true critique of “politics” that one finds in the film, the Populist distrust of politics so deeply embedded in American ideology). Lincoln playing a role, or Lincoln-S, is associated with Politics, Law, Death, and interestingly enough, with the Theater or at least with theatricality (perhaps an important indication of artificiality).

Lincoln at the jail door as law enforcer and politician: Lincoln Standing

Lincoln-R is associated with Nature, Woman, organic community life (“You all know who I am”, the words with which Lincoln opens his first speech in the film) and rural America. When Lincoln-R is forced to become Lincoln-S he is all at ease, violent and emotionally detached. At the party given by Mary Todd, people don’t know who Lincoln is (“Mr. Lincoln, are you by any chance one of the Lincolns of…”). Lincoln is out of place ? or is simply not placed by those around him.

When he steps out onto the balcony with Mary Todd, Lincoln immediately detaches himself from Mary. She moves to the background, Lincoln in the foreground gazes out at the river, and the Ann Rutledge music theme comes up. Lincoln-R has stepped out of the role of Lincoln-S. Lincoln-R yearns to be alive, to put an end to his “uprootedness” and to avoid the inevitable fate which includes assassination in the theatre.

Lincoln’s attempts to come alive largely take the form of inserting himself into the Clay family, of substituting the Clay family for his lost/dead family.

The balcony scene is immediately followed by Lincoln’s ride to the Clay farm. Significantly, Mrs. Clay, in the scene at her farmhouse, refuses Lincoln entry into her family, precisely because he doesn’t understand that Law of the Family; he insists on asking Mrs. Clay to tell him which one of her sons killed Scrub White. She refuses, of course. And she refuses Lincoln with exactly the same words ? “I can’t, I just can’t” ? with which she refuses Felder, the prosecutor, during his vicious examination of her during the trial. While it is true that Lincoln is opposed to Felder in the adversarial proceedings of the court trial, it is also true that they are united under the sign of the Law and this Law is opposed to the figure of Mrs. Clay, who represents the Law of the Family.

The entire movement of the film is toward Lincoln’s education in the Law of the Family and his entry into the Family. At first, Lincoln seeks to divide the Family by his insistence on an either/or Law (“Which of your sons killed Scrub White, either Matt or Adam?”) but learns that the Law of the Family is the Law of both/and, the Law of unification.[6] This dawning realization is most important when Lincoln intervenes in Felder’s third degree examination of Mrs. Clay by telling Felder and the court that “I may not know much of the Law but I know what’s right and what’s wrong” (compare this to his earlier statement about rights and wrongs of property in the scene by the river to see how much ground Lincoln has already traversed in his education into the Higher Law): then, turning to Mrs. Clay, he says, “I’d rather, Mrs. Clay, see you lose both your boys than to see you break your heart trying to save one at the expense of the other. So don’t tell them.” Lincoln’s education is almost complete; all that remains is for him to read the almanac ? a manual for country living, the workaday bible of rural yeomanry, the inscription of the analogical processes of Nature.

Cahiers seems to understand, at some level, that their cornerstone, Nature/Law/Woman, provides a shaky foundation at best. They try to bolster that foundation with this piece of specious reasoning:

Just as culturally determined and codified as the relationship Nature-Woman, the equivalence Nature-Law is here underlined precisely by the fact that the Law Book is Blackstone, for whom all forms of Law (the Laws of gravitation as well as those which regulate society) grow from a natural Law which is none other than God’s law.

There is no evidence in the film that Blackstone’s Law has anything to do with Natural or Divine Law. This may be true in other places but it cannot be substantiated by reference to the film. We consider this kind of reasoning to be illegitimate at this point in the discussion of the film. (Clearly what is happening here is that Cahiers wants to force the film into a preconceived mold around their ideas of capitalist theology, the Law of Capital, and Natural and Divine Law and Ford’s assigned place in that configuration. This causes them to miss a vital contradiction in the film, arguably the one which structures the entire text: the opposition between the Law of Capital and the Law of the Family).

Furthermore, while it is true that Blackstone’s Law is related to God’s Law (in Lincoln’s speech to prevent the lynching and in Felder’s initial presentation to the jury) it is never related ? in the film ? to Natural Law, i.e. to Woman or the Law of the Family. It is Felder and Lincoln who invoke God’s Law, not Mrs. Clay. Remember that Mrs. Clay needs help from Lincoln in order to swear on the Bible preceding her testimony at the trial. And remember that it is Felder again who invokes God’s Law during his cross examination of Mrs. Clay when he tries (unsuccessfully) to make her reveal which of her sons killed Scrub White. At this point, God’s Law is clearly in opposition to the Law represented by Mrs. Clay. Lincoln is finally forced to intervene in order to save Mrs. Clay, and the discourse of his intervention is absolutely crucial. He does not intervene on behalf of Blackstone’s Law, i.e., he does not break in to make a point of law ? rather he intervenes by saying “I may not know much about law but I know what’s right and wrong.” And he is not talking here about the rights and wrongs of property, but of trying to force a mother to break up her family.

The points made above show the anomalies between Cahiers’ interpretation and a close reading of the film. With these discrepancies in mind we are forced to consider a new reading of the film, one which is better able to take account of the gaps, differences, oppositions and contradictions between Cahiers’ reading and the film that our close reading has revealed. Let us propose then a different conceptual arrangement with which to inform our further readings of the film. As with any conceptual arrangement, if more valid than Cahiers’, it will provide a higher degree of coherence as well as a higher level of complexity of organization.

The conceptual arrangement we propose has two sets of triadic equivalencies whose relationship to one another is that of opposition. The first set is Nature/Woman/Life and is opposed to another set, Man-without-woman/Death/Law. The figure of Lincoln constitutes a dynamic tension between these two opposing sets and, at the same time, is a movement from the former to the latter, and then the transcendence of their opposition under the sign of a higher unity.

We will now retrace our initial reading of the film under the signs of this conceptual arrangement, which is the product of our theoretical activity.

2.

The adumbration of the mise en scene is too critical ? and too long ? to be simply a series of parenthetical statements of our concern with thematic significance. We do not make a facile distinction between style and theme (see Abramson, “Structure and Meaning in the Cinema” in Nichols, ed., Movies and Methods) nor do we reduce one to the other.

We don’t seek an empirical reading of the elements of mise en scene uninformed by any theoretical practice but, at the same time, we don’t seek an elaboration of theme on the basis of a narrative analysis.

We avoid the error of empiricism: i.e. of assuming that knowledge is produced by sense impressions received from the film (in film criticism, this error takes the form of a formal elaboration of the elements of mise en scene coupled with some intuitive grasp of their significance). We also avoid the error of structuralist-rationalism: i.e. of assuming that knowledge is produced by a theoretical practice apart from any empirical work on the film (in film criticism, this error takes the form of either the elaboration of a set of structural antinomies, or the elaboration of a set of preconstituted [a priori] conceptual arrangements which is considered sufficient for a scientific understanding). Empiricist criticism tends to reify the text while structuralist-rationalist criticism tends to obliterate it.

The differences between Cahiers’ position and our own is between an interpretation which claims a scientific status for its procedure but, in fact, has no procedure for verifying or validating its interpretative schemes; and an interpretation which understands itself as a hermeneutic, which is constantly clarifying its conceptual categories and testing their adequacy against the text. The former believes its categories exhaust the meaning of the text (which is why it is necessary to suppress so many aspects of the text), while the latter understands itself as a dialogue with the text as well as with other interpretations. This distinction is meant to emphasize that our procedure involves a rigorous testing of our theoretical production against the text. Cahiers’ procedure tends to eliminate from consideration any elements of mise en scene that contradict its theoretical practice, while our procedure involves a thorough and systematic testing of our theoretical production against the text. Our procedure is empirical without being empiricist.

But let us be clear about the place of mise en scene analysis in our overall project. We do not believe that a “close analysis” of a film, no matter how rigorous, ever “proves” the validity of a particular interpretation. However, we do believe that a “close analysis” of a film can provide evidence which disproves or at least brings into question the validity of a particular interpretation. In this sense, a “close analysis” can provide evidence which will necessitate a more comprehensive interpretation scheme as well as provide material for resolving a conflict of interpretations. The evidence for our disagreement with the Cahiers interpretation is to be found in the following analysis of the mise en scene.

1. Iconic costume. The first of these, and the most easily recognized, is Lincoln’s costume. In the film, Lincoln is introduced wearing jackboots, homespun pants, suspenders, and a light homespun shirt ? all tones of grey; this costume is in marked contrast to the formal dark suit of Stuart, the professional politician. Lincoln continues to wear this costume in the summer scene by the river with Ann Rutledge. It isn’t until Lincoln visits Ann’s snow-covered grave that we see him in another costume: thick winter coat, muffler, and coonskin cap. This costume is the transition between the loose, airy, casual dress of the first scenes and the formal, funereal black outfit he wears through the rest of the film. As Lincoln enters Springfield to join Stuart’s law firm, this outfit becomes a symbol for the consequences of Ann’s death upon Lincoln’s future vocation.

This iconic shift segments the film in a significant way. In the scenes before this costume shift, Lincoln is presented as the prototype of the agrarian myth: his politics are simple and direct, his attitude is modest and charitable. His economic relationships with others are the prototype of symbolic exchange ? non-equivalence and reciprocity. This can be contrasted to Lincoln’s first acts as a lawyer in the Plaintiffs scene, in which he settles a civil dispute marked by greed, vindictiveness, deceit, and physical violence; the over-determined symbols of these new relationships which Lincoln now experiences are the Law and money. It is in the scenes with Ann Rutledge before this iconic shift that we are presented with Lincoln’s emotional life as a present reality; this human dimension of Lincoln is emphasized in his interior monologue. After the shift, he discusses his emotional life as if it were buried in the past. It is as if Lincoln were now dead, unable to enjoy life in the present, only able to experience the present impulses of his anima by rerouting them through past associations.

The costume is significant by its absence in the scene at the Clay farm. Lincoln’s black outfit, already established as a symbol of death and the Law, is shed (more accurately, altered to resemble his country costume) in deference to Mrs. Clay and what she represents.

2. Eyes. Cahiers has made a great deal of Lincoln’s harsh and intimidating gaze (calling it “castrating”) and has specified its instances in the film. For example, in the Plaintiffs scene, when one of the plaintiffs tries to pass off a counterfeit coin as payment for Lincoln’s legal services, Lincoln’s intimidating gaze is given to us in full frontal shot, further emphasized by its privileged position as the last shot in the scene. The gaze is presented in this way again throughout the trial scenes, particularly during the second testimony of J. Palmer Cass. What is interesting here is that by the time of Cass’s interrogation, the gaze has become so deeply inscribed in the viewer’s consciousness that the gaze itself need not be shown, but rather replaced in the shot sequence by the image of its effect, i.e. Palmer Cass ? what we can see of him past Lincoln’s black back ? squirming in the witness stand.

This same strategy is employed in the final scene, when Carrie Sue kisses Lincoln, then starts and draws back from Lincoln’s forbidding presence. His gaze is never shown to the viewer, but Carrie Sue’s reactions are the sign of that unseen presence which is the denial of sexual pleasure.

3. Triangles. Outside of one-shot close-ups, two types of shots recur. The first type shows three people, usually in medium close-up, sometimes in medium long shot, inserted in the decoupage of reaction shots. The most prominent of these are of Mrs. Clay with Carrie Sue and Sarah, or of Mrs. Clay with Matt and Adam (see examples in the Fourth of July celebration scenes, the murder and lynching scenes, and the trial scenes). These reaction shots strengthen the imagery of threes which is more actively presented in shots built around Lincoln.

In the second type of shot, Lincoln is at the center of the frame, in the middle ground, slightly high of center, dominating and facing us. In the lower right and left foreground, sometimes silhouetted, lower in the frame (cut by the bottom frameline) are two similar objects: pieces of pie, heads, figures. The triangle becomes a visual metaphor for the problematic (in the Althusserian sense: the theoretical or ideological framework within which a word or concept is used) of the entire film: the choices presented to Lincoln and how he chooses to make them. The pie-judging close-up is analogous to the trial scene shots of Lincoln framed by Adam and Matt’s backs in the courtroom (this is part of the film’s strategy of repeating the conceptual paradigm at different levels). The first part of the narrative presents us with a set of either/or choices (choose for or against the Law; stay in New Salem or leave; the apple or the peach pie), which can only be resolved by the choice of one or the other; whereas the use of triangular/three-part imagery raises the most basic visual challenge to the binary law of twos, particularly in the Plaintiffs and pie-judging scenes, where Lincoln’s resolution is both/and.

4. Visual Perspectives on Lincoln. Most shots in the film are eye-level or, sometimes, adjusted to look up at Lincoln. Key exceptions involve Mrs. Clay. At the end of the lynching scene, as Lincoln says goodbye to Mrs. Clay, Sarah, and Carrie Sue at their wagon, we have five high angle shots of Lincoln, who is seen behind a mule’s back, his face halved by the reins. These shots are a critical set of signifiers, stressing by their repetition the contrast between Lincoln as the representative of the Law and Mrs. Clay as the representative of the Family. This visual perspective is the correlation of the superiority of the Law of the Family to the rule of Law. This higher scheme must be contrasted with their existential position at this point in the narrative: Mrs. Clay’s family is in danger of being broken up; in a strange environment, she is unable to deal with Blackstone’s Law; Lincoln is in the position of defender and helper of the family, having just broken up the lynch mob. Therefore, one would expect to find a shot strategy which emphasized Lincoln’s dominance over Mrs. Clay, perhaps from Lincoln’s POV, and the reverse, perhaps from Mrs. Clay’s POV. However, this is not the case: that expected visual relationship has been inverted ? and subverted.

Reverse, Lincoln looking up at Mrs. Clay

Reverse, Mrs. Clay looking down on Lincoln

The relationship of Mrs. Clay to Lincoln is continued in the scene at the Clay farm where Lincoln receives the gift of the almanac, which turns out to be the answer to the question, “Which of your sons killed Scrub White?” Mrs. Clay’s dominance over Lincoln is carried through in the mise en scene here as well. Lincoln sits on the steps of the porch, below and at the feet of Mrs. Clay. When Lincoln asks Mrs. Clay which of her sons killed White, we are given the most unbalanced shot in the film. At this point, Lincoln sees this as the key question, thinks Mrs. Clay knows the answer, and assumes that she will tell him in his role as lawyer and protector. Mrs. Clay’s refusal of Lincoln’s question is also a refusal of Lincoln’s stressed overtures in this scene for entry into the Clay family. The asking of the forbidden question threatens the unity of the family and the order of the film’s visual universe. This threat of the question is visualized as a threat to the stability of the frame. Upon hearing the question, Mrs. Clay leaves the intimate space that she and Lincoln have shared; she stands, photographed in a low angle shot, at the left side of the now unbalanced frame. Then Lincoln stands into the shot as well, at the right side, but is unable to balance the composition ? he and Mrs. Clay are now the two prominent, disordered diagonal elements of the frame. It is, of course, a binary composition. When he retracts his question and takes an alternative tack, he and Mrs. Clay remain in the same plane (this plane-sharing is quite unusual for Lincoln) in a balanced, harmonious shot ? he puts his arm around her shoulder.

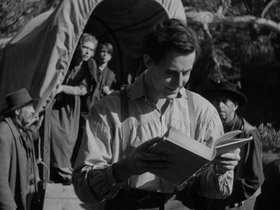

Lincoln reading Adam’s letter to the Clay family

Mrs. Clay refuses Lincoln’s question – I

Mrs. Clay refuses Lincoln’s question – II: the answer (the almanac) is in his hand

3.

Using a model which emphasizes Lincoln’s character in the process of change and development – as opposed to Cahiers, which sees the Lincoln character as a static figure whose sole function from beginning to end is the inscription of the Law in the name of the Father ? our reading establishes a double set of triadic equivalencies in opposition to one another. Therefore, our model can account for the development of Lincoln’s character in the film by seeing it as the embodiment of a dynamic tension and dialectical movement between the two opposing sets of triadic equivalencies: Woman/Nature/Life; and Man-without-woman/Law/Death.

Our reading of the film regards the Lincoln character in a process of change and development, a movement from innocence to the sophistication of the Law, the establishment of a binary opposition between them (innocence, and city/Law), and the overcoming of these oppositions under the sign of the Family. In this reading, we see seven scenes as critical loci of signification.

1. The electoral speech (establishment of Lincoln’s innocence).

2. Wagon scene no. 1 (Lincoln receives the lawbook from the Family; initiates Lincoln’s role as the inscriber of the Law).

3. Ann Rutledge’s death (Death marks the break with the innocent past; completes Lincoln’s initiation into the Law).

4. Wagon scene no. 2 (mise en scene establishes Mrs. Clay’s dominance over Lincoln and the Law).

5. The farm (beginning of Lincoln’s – as opposed to our – recognition of the power of The Law of the Family as opposed to the power of the Law).

6. Lincoln’s active intervention to protect Mrs. Clay in the courtroom (this action signals that Lincoln now, himself, subordinates the Law to The Law of the Family).

7. Wagon scene no. 3 (farewell scene, with debt and gratitude – the exchange of money. Ostensibly, Lincoln now is part of the Family as well as its protector).

1. The Electoral Speech. Initial State. Lincoln’s Innocence.

Lincoln is first presented in contrast to Stuart the lawyer-politician through costume, physical position and movement, rhetoric and style of delivery – as well as camera placement, editing and lighting. The contrast emphasizes Lincoln’s qualities of simplicity, clarity, modesty, and down-homeness. The cutaway at the end of his speech to the frolicking boy and girl suggest Lincoln’s innocent virtue as well as the virtues of innocence. This striking shot – striking because this non-diegetic cut has no counterpart anywhere else in the film, or in most of Ford’s work – has no place in the Cahiers treatment – because it highlights Lincoln’s innocence, whereas Cahiers does not regard Lincoln as innocent at any point in the film.

2. Wagon Scene No. 1.

Lincoln crosses the square to the Clay family wagon, where he is told by Mr. Clay that the family has no money and is in need of supplies. Mrs. Clay is uneasy about accepting credit from Lincoln, and offers him a barrel of books in exchange. Lincoln selects one of the books: Blackstone’s Commentaries.

Lincoln receiving the Law book

Shift in placement of the Father

The mise en scene establishes a pattern of relationships that will be followed throughout much of the film. As Lincoln moves around the wagon, Mr. Clay – the father – nearly disappears, severed by the frameline. Lincoln is in the foreground, lower and fully lit; Mrs. Clay and the two boys are framed in the proscenium of the wagon-hoop, also fully lit. The composition effectively cuts out the father and joins – without equating – Lincoln as one unit, and Mrs. Clay and sons as the other unit, so that visually Lincoln receives the Law from a patriarchal family at the same time he replaces the father of the family.

Lincoln’s role as inscriber of the Law thus parallels his attempt to be the protector of the family. While it is clear from the visual relationship between Mrs. Clay and Lincoln that the role of the family is privileged – framed, set on its own plane behind and above Lincoln, effectively idealized through the conventions of late eighteenth and nineteenth century American popular portraiture – it is also true that the narrative establishes that the family is illiterate and has no knowledge of the Law, and the visuals contain the sense that the family and the Law are quite distinct, different if not opposed. So we can say here that while the Family is not the Law, it is the carrier and the source of the Law, and is given to Lincoln as a sacred trust, part of a system of symbolic exchange that will be elaborated throughout the film (this is not a system of “barter”, nor a “circuit of debt and repayment” as Cahiers would have it).

3. Ann Rutledge’s Death.

The two scenes just discussed and the two riverside scenes with (live/dead) Ann Rutledge comprise the film’s presentation of Lincoln’s innocence (i.e., that he has not yet been introduced to the city, not yet become a lawyer, and not yet become entangled/fascinated with power – the Plaintiffs scene, etc.) and the death which marks the complete break with that innocence. We have already discussed the major iconic shifts which accompany the death. What must be emphasized here is the equation of Death with the Law.

The wintry scene is critical to the entire project of the film because the meaning of the signifiers, ambivalent in the summer scene by the river, here is crystallized. In the previous scene, Ann represented womanhood as potentiality, in contradistinction to womanhood proper, i.e., motherhood. For this reason, the immature Ann could be associated both with Nature and the Law (although more clearly identified with the former than the latter). Ann as signifier – Ann alive but unmarried – was a kind of “floating signifier”; upon her death, the meaning of this signifier becomes fixed. Now, as the dead Ann, she becomes clearly associated with winter (the freezing of emotions), with Death, and with the Law. This analysis makes clear the determining function of Death in the film with regard to other signifiers – iconic and otherwise. Now Lincoln, as Man-without-woman, becomes part of a new matrix of signification, namely Man-without-woman/Death/Law, which opposes him to Woman/Nature/Life, which will be represented by the Clay family women.

The scene presents us with a tension between the verbal discourse and the visual imagery: while Lincoln tells us it is Spring, the visuals tell us it is Winter. The visuals are a sign of Lincoln’s emotional state: it will always be Winter for Lincoln. Lincoln as historical/mythical figure (Lincoln-S) desires to be dead, to complement his emotional death with a physical death. But a part of Lincoln (Lincoln-R) resists; he desires to go back to a previous state, before Ann Rutledge’s death. But if this desire were realized, the film would end. This desire conflicts with the desire of the narrative (desire of the text) to go on. Therefore, only the verbal discourse informs us that it is Spring; it conveys the desire of the text for Lincoln to go to Springfield and practice Law. The visuals, on the other hand, convey Lincoln’s desire to remain in Ann’s presence (there is no question here, Cahiers notwithstanding, of Lincoln’s resurrection; what is resurrected is the narrative).

Therefore, there are conflicting desires in the text: Lincoln’s desire to remain with Ann, presented to us primarily through gesture and visual style; and Lincoln’s desire to go to Springfield and practice Law, given to us primarily through the verbal discourse. There is also the desire of the viewer to have the film continue, for which Lincoln-to-leave-Ann is obviously necessary, as well as the desire of the text itself for Lincoln to assume his role as President and Unifier of the nation. It is clear that the desire of the text will prevail, but it is important to note the gap between the desire of the text, presented as Lincoln’s desire to go to Springfield, etc., and the visual inscription of desire in the text, presented as Lincoln’s desire to be relieved of the death-role he must play. The film’s unsettling effect on the viewer is born here, in the insistence of the film to have it both ways: to be alive and to be dead, both inscribed in the text under the sign of Desire – a struggle between Eros and Thanatos. This struggle is mediated through the Clay family wherein Lincoln attempts to transform the relationships of a dead past into a living present.

4. Wagon Scene No. 2.

Lincoln has just rescued Matt and Adam from the lynch mob. He goes to the wagon to reassure Mrs. Clay, Sarah, and Carrie Sue as they prepare to leave for their farm; Lincoln has here assumed the role of protector.

We want to stress that at this point in the film Lincoln is fully identified with the Law (prohibition of violence and pleasure, as in the lynching scene), and with Death. The mise en scene establishes that Mrs. Clay’s law, the Law of the Family, is on a different level from Lincoln’s Law. What is interesting here is that their respective perspectives, on the relationship of these two levels, are not in common – not conveyed by the mise en scene as the same. We have already discussed the powerful and repeated high angle shot on Lincoln from Mrs. Clay’s POV. What signals the contrast in consciousness is the fact that the high angle shot on Lincoln from her perspective is not complemented by a low angle shot on Mrs. Clay from Lincoln’s perspective – i.e. a shot which shares the axis around which the camera organizes the visual perspectives. The master shot establishes the axis of their mutual glance.

However, the axis around which the camera organizes the visual perspectives for the reverse one-shots – usually the same as the axis established by the master shot – is here used only for the high angle shots down on Lincoln from Mrs. Clay’s POV, which establish her superiority over Lincoln. The reverse one –shot on Mrs. Clay from Lincoln’s perspective is on an angle almost that of eye-level. This indicates: first, that Lincoln and Mrs. Clay do not share the same worldview; second, that Lincoln’s view is the lesser one; and third, that Lincoln does not yet recognize the superiority of the Law of the Family. This strategy is striking because the film has few one-on-one cutting sequences, and because among those other few, the prominence of the two figures is either equal or slightly tipped in Lincoln’s favor.

5. The Farm.

Lincoln’s education in the Law of the Family continues during his visit to the Clay farm. There Lincoln attempts to make himself part of the Clay family by drawing direct analogies between his lost family and the family he wishes to join (his mother, Nancy Hanks, with Mrs. Clay; his sister Sarah with Sarah Clay; Ann Rutledge with Carrie Sue). Lincoln’s attempts to become part of the Clay family do not succeed because Lincoln at this point still insists on the rule of Law as the supreme authority. Mrs. Clay’s rejection of Lincoln’s question is also a rejection of himself: under the Law of the Family, a member of the family would never make the demand Lincoln has made, because the demand (to answer the question) embodies and is the desire to divide the family. Lincoln is not yet ready for his role in the Family, just as he is not yet ready for his role in the Nation.

However, Mrs. Clay’s rejection of Lincoln is not absolute (nor does Lincoln take it as absolute: the moment of her rejection is by far the most disharmonious moment of the mise en scene; but it is immediately followed by an extremely harmonious image, Lincoln and Mrs. Clay in the same plane, perpendicular to the camera, shot from slightly below their eye levels with a neutral, squared background behind him; and Lincoln puts his arm around her shoulder, the only time – along with his carrying Ann Rutledge’s flower basket – that Lincoln initiates physical contact with anyone in the film); the Clay family presents Lincoln with a gift, unconsciously, to be sure, and whose significance is not at all understood by Lincoln (these last two points contrast sharply with the gift of Blackstone’s Commentaries at the beginning of the film).

6. Lincoln’s Intervention to Protect Mrs. Clay at the Trial.

Lincoln intervenes at the trial

Felder the prosecutor calls Mrs. Clay to the stand as a hostile witness. By invoking both God and the Law he attempts to coerce her into telling him which of her sons killed Scrub White. The cross-examination of Mrs. Clay by the prosecutor is relentless – unbroken by any of Ford’s deflating humor – and merciless. Lincoln allows the examination to escalate until it becomes necessary for Mrs. Clay to cast desperate glances in Lincoln’s direction (he is off-screen). No reaction shots of Lincoln are given, making his absent presence all the more powerful. Lincoln allows the cross-examination to continue; he, too, wants to know the answer to the forbidden question; he, too, is a prosecutor: the words which Mrs. Clay used to answer Lincoln’s question at the farm are exactly the words she uses to answer (refuse) Felder’s question in the courtroom. Lincoln and Felder at this point both stand under the sign of the Law; this makes Lincoln’s intervention that much more dramatic (along with its presentation: Lincoln’s interrupting voice comes from off-screen, startling us, as Ann Rutledge’s did in the first riverbank scene) and impressive in its gravity, authority, power; his voice stills the courtroom so that his words stand alone; Felder looks over, breaking off his obsessive oration. It is for Lincoln a leap of faith – from the Law of the Social Order to the Law of the Family. He hasn’t yet read the almanac; the truth is there, but for the truth to be revealed, an act of Faith is required (“Seek and ye shall find”). Lincoln’s leap – not an act based on knowledge, because he has not yet read the almanac – activates the truth which is the answer, contained in the almanac (so far only latent or potentially there).

After reading the almanac (which we feel he has done the night before, in the scene at his office when the Judge comes to advise Lincoln to seek help form a more experienced legal hand) Lincoln is now fully the agent of truth. It only remains for him to coerce – through the Law – the truth from J. Palmer Cass. Here, finally, the Law is in the service of the truth. The almanac here serves two intertwined purposes: 1) as an analog signifier of Nature, it provides Lincoln with the means for his victory in the courtroom; 2) as the inscription of the both/and, it prepares Lincoln for his role as President. The former secures the unity of the family while the latter secures the unity of the Nation. The final scene links these two processes or tasks together.

7. Wagon Scene No. 3.

The final scene with the Clay wagon is over-determined, which we expect, and apparently arbitrary, which we don’t expect. Lincoln bids his farewell to the now-united family after receiving a few coins from Mrs. Clay. The circuit of symbolic debt and exchange is now closed – or so it seems. The wagon in front of which the scene has been played moves out of frame revealing Carrie Sue and Adam facing Lincoln (and the camera). We are not prepared by the film’s style for this space-transforming event (the film’s method has been to lay space out very clearly at the beginning of sequences and shots, and not to change space significantly during shots).

Given the mother’s privileged position in the film, we would expect that the resolution of Lincoln’s relationship with the Clay family would finish with his dialogue with Mrs. Clay. That this is not the case surprises the viewer, and it does so through mise en scene. In narrative terms, we expect all family members to be in the wagon as it leaves for the farm; instead, Carrie Sue and Adam are left behind as the home/wagon exits. Ostensibly, Lincoln’s desire to be both protector of the family and a member of the family has been fulfilled.

His emotional needs as regards family seem settled (Nancy Hanks-Mrs. Clay; Sarah-Sarah). But his emotional/sexual needs regarding Ann Rutledge are still unsettled. Carrie Sue’s feelings toward Lincoln are more or less explicitly sexual throughout the film, and her remark, “I reckon I’d just about die if I didn’t kiss you, Mr. Lincoln” confirms this. Up to this point, we have argued that the general movement of the film is from life to death to rebirth; but Lincoln’s castrating figure (we don’t even see the castrating glance Lincoln gives Carrie Sue here, but we suffer its effect through the look on her face) leaves us with this final impression: that the process of rebirth has not been able to overcome the inevitable.

In the end we experience a contradiction between: the ideological project of the film, whose purpose it is to fulfil the conflicting desires of the textual system – Lincoln’s desire to become part of the family, to be emotionally reborn (largely inscribed in the mise en scene) and the necessity of a Historical Fate (here inscribed as the desire of the text for Lincoln to play his historical role and meet his Fate). The desire of the text, of course, prevails, but the textual inscription of the Lincoln character in the film – his separateness from everything around him – is the mark of a deep contradiction, one which suggests the text’s ambivalence toward History and Politics.

Lincoln desires to follow the wagon, to be part of the Clay family. He cannot. The wagon disappears and with it Lincoln’s last hope of life. Lincoln turns to stone: he has become myth.

CONCLUSION

Our analysis of the film shows that contradictions which reside in the overall textual system are rooted in an ideological deep distrust of History and Politics, “Civilization” and Law, hence the rule of Capital. This is decidedly different from Cahiers which understands Lincoln solely as the figure of that Law and the instrument of its inscription. Cahiers understands the contradiction to be between the Law and its overly violent and repressive inscription.

Lincoln as Old Testament enforcer of the Law at the attempted lynching

Our interpretation posits a contradiction at a much deeper level – that of the Law itself. While Cahiers sees only one Law operating in the film, we see two conflicting Laws (actually three if we consider God’s Law, but this Old Testament Law is invoked by Felder, and by Lincoln when he defends the Law to the lynch mob. And thereby God’s Law is always associated with the Law of the State) and their conflict is the motive force of the film’s development.

Cahiers’ analysis suppresses crucial elements of the text, most notably Lincoln’s conflict with Mrs. Clay and his identification, because of that conflict, with Felder against Mrs. Clay. Lincoln’s resolution of that conflict – i.e. his understanding that Mrs. Clay represents a Higher Law than Felder, that the Law of the Family in the name of the Mother is higher than the Law of the State in the name of the Father – is also the resolution of the question “Which of your sons killed…” The answer hinges on the almanac, the “gift” of the Clay family, but Lincoln’s reading of the almanac, i.e. his understanding of the “gift” in turn hinges on his coming-to-understand that Mrs. Clay represents a Higher Law (“I may not know much about the Law, but I know what’s right and wrong”). We suggest that the contradiction between these Laws that structure the entire text is so profound that to simply read the film and the resolution of this contradiction as the naturalization of bourgeois law is to misunderstand the ideological meanings of the entire text.

The ideological structures of the film, as revealed by a rigorous analysis, are highly complex and demand a highly complex and coherent critical comprehension that Cahiers’ Marxist (Althusserian) – Freudian (Lacanian) reading cannot provide. It is our feeling that our interpretation, which accounts for the contradictions in the inscription of the Lincoln character in the film as well as the contradictions between the Law of the Family and the Law of the State can provide that level of coherence and complexity.

The authors are grateful to Alan Curl, whose discussion of the trial scenes sparked much of the visual analysis herein; and to Dudley Andrew, Greg Lukow, and Steve Seidman for their valuable suggestions; and to the students in Ronald Abramson’s Film History 179 Seminar at University of California at Santa Cruz. And for typing and proofreading the final manuscript we are indebted to Nita Esterline, Betsy Queen, and Valerie Cardoza.

Endnotes

[1] Actually, a piece of film criticism in this form may be interrogated at four levels. 1) The specific reading of the film may be questioned in terms of the meta-language the critical system employs. 2) The critical system itself may be questioned. 3) The critic’s understanding of the critical system may be questioned. In the case at hand, this would mean questioning Cahiers’ understanding of Althusser and Lacan. 4) A specific reading of the film may be presented in terms other than those proposed by the initial reading (this would most likely imply the use of another critical system). The first part of our essay works primarily at the first of these levels and the second part will work on the second of these levels.

[2] From “John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln,” Cahiers collectif, Screen as cited above: “It is worth recalling that the external and mechanistic application of possibly even rigorously constructed concepts has always tried to pass for the exercise of a theoretical practice: and – though this has long been established – that an artistic product cannot be linked to its socio-historical context according to a linear, expressive, direct causality (unless one falls into a reductionist historical determinism), but that it is a complex, mediated and decentered relationship with this context, which has to rigorous specified (which is why it is simplistic to discard ‘classic’ Hollywood cinema on the pretext that that since it is part of the capitalist system it can only reflect.” While it is true that Cahiers does not dismiss the entire film, it is nonetheless true that Cahiers’ assumption of the ideological project of the film is “external and mechanistic”.

[3] We see this as the same problematic as the relationship of American populist ideology to U. S. monopoly capitalism.

[4] Furthermore, Cahiers’ assertion that morality in the film is an idealist mask for politics conveniently forgets that politics is an idealist mask for economics; and it should also be remembered that the usual discussion about the morality (Higher Law) of slavery – which is the way Cahiers discusses it – is presented in the film as a discussion of the economics of slavery. Who’s being idealist here anyway?

[5] The Cahiers critics may suggest here that it is not they who reduce and repress opposition to the Law of Capital, but the system itself which does it (it is certainly not the “system” of the film which reduces the Law of the Family to an epiphenomenon of the Law of Capital). But their interpretations are then no more than “reflections”; a vicious circularity ensues in which every text turns out to be exactly what Cahiers believes “bourgeois ideology” to be. All is “known” in advance. The Marxist ideologues simply reveal to us the workings out of this “bourgeois ideology” in the text. The concept of an “active reading” has become a means for suppressing all other possible readings. This dogmatism is covered over by appeals to the “real” to “material reality,” and to a procedure under the sign of “science” – justified as a theoretical production corresponding to an “objective reality.”

The system Cahiers seeks to interpret winds up interpreting them. The dialectic is frozen; the categories are universalised; the system is reinforced.

It is not tautological that the concept of history is historical, that the concept of production is itself produced (that is, it is to be judged by a kind of self-analysis). Rather, this simply indicates the explosive, mortal present form of critical concepts. As soon as they are constituted as universal they cease to be analytical and the religion of meaning begins. They become canonical and enter the general system’s mode of theoretical representation. Not accidently, at this moment they also take on their scientific cast (as in the scientific canonization of concepts from Engels to Althusser). They set themselves up as expressing an “objective reality.” They become signs: signifiers of a “real” signified. And although at the best of times these concepts have been practiced as concepts without taking themselves for reality, they have nonetheless subsequently fallen into the imaginary of the sign, or the sphere of truth. They are no longer in the sphere of interpretation but enter that of repressive simulation.

– Jean Baudrillard, The Mirror of Production, p. 48; trans. Mark Poster. St. Louis: The Telos Press, 1975.

[6] The signifiers, respectively, of those two kinds of law are Blackstone’s Commentaries (either right or wrong) and the almanac (Law of Nature through cyclical rhythms such as – significantly for this film’s plot – the phases of the moon). The first is given to Lincoln by a family with the father present, the latter given by the family with the father absent – another difference that Cahiers neglects.

Created on: Saturday, 15 December 2007