Figure 1. The Kiss, Auguste Rodin, photographed by Eugene Druet, c. 1900.

Part of a series of photographs in the collection of the Musée Rodin in Paris taken of The Kiss at various times of day.

The rise of digital technology in filmmaking has brought us back to fundamental questions about the object of cinema studies. In this context, I am interested in thinking about film as its nature and limits are reflected upon by the work of avant-garde filmmakers through an appeal to the classical medium of sculpture. In this essay I focus on Maya Deren’s 1946 Ritual in Transfigured Time in considering how and why the avant-garde makes this appeal, what the incursion of sculpture in a film does to our experience and understanding of the relationship of film to the filmed object and event, as well as the creative work of the filmmaker. By incorporating sculpture in a moving image-orientated meditation on ritual and movement, Deren suggests a return to the moment in which visual reproductions fundamentally changed aesthetic understandings of other media, primarily the distinction made in the history of aesthetics between the spatial and the temporal arts. To understand the place of sculpture in relation to the still and moving image in Deren’s film, I would like first to consider a sculptor whose life and work coincided with the invention of film, Auguste Rodin. Georg Simmel’s description of Rodin as the “artist most representative of the late 19th century,” suggests that the same fever for archive and anxieties about the wane of sensory experience in an age defined by the fleeting encounters prevalent to the reality of the 19th century city, inspired Rodin’s experimentations with fragmentation, but by 1890, we also see Rodin responding to and incorporating photography into his sculptural works. In both instances (Rodin responding to photography and Rodin responding photographically), I would like to argue, the iterations of temporality in Rodin’s sculpture, a temporality once believed to ascribe ineffability to music and poetry, pervade as productive and excessive moments of loss in the quintessentially spatial art of sculpture. What since G. E. Lessing’s 1766 Laocoön [1] was understood to be an art of simultaneity becomes an art of succession.

I will pay particular attention to the role of photography in Rodin’s sculptures and his various reproductions of them but I would also like to propose viewing his break with analogic representation in sculpture not only as a response to emerging technologies of visual reproduction (a decided resistance to the motion studies of Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge that Rodin disdained for their promotion of the automations of science over the creative role of the artist), but as emerging from the same zeitgeist as photography and cinema’s prototypes. Indeed, Rodin’s place in late 19th century Parisian modernity characterized by flux, mobility, change and exchange, by friends and contemporaries of Rodin like Georg Simmel and Charles Baudelaire, suggested an essential aesthetic paradox of how sculpture as a medium of simultaneity and contained space was to face a world increasingly fractured by speed and movement. The anachronistic tension at work in Rodin’s art, between his medium and his time, arises again with Maya Deren’s cinematic appeal to sculpture as the filmed sculptural object that at once resists and partakes of the movement of the film’s images and of the camera. The resistance so staged questions the analogic capabilities of sculpture and film by using the photograph or the still image in opposition to the moving image (the part brought into relief by the whole in which it participates) to create uncertainty in the very place of positivist claims to and epistemic truth implied by the indexicality of the photographic and the filmed image.

In Reading the Figural, or, Philosophy After the New Media, David Rodowick argues that film has always faced problems in its relationship to the history of aesthetics by being both a spatial and a temporal art form, conflating the strict division Lessing set up between arts of simultaneity like sculpture and painting and arts of succession like music and poetry (the latter of which, in aesthetics, are believed to come the closest to the pure activity of thought and spirit). As Rodowick rightly points out, by partaking of both kinds of art, successive and simultaneous, temporal and spatial, film represented an ideal synthesis of the arts for its defenders and also for those who took the position that film could never be an art because it fell into neither category, and because its character was thought to be derivative of its sister arts rather than unique to itself. Rodowick argues in this book that:

… the emergence and proliferation of digital media exacerbate these problems. Unlike analogical representations, which have as their basis a transformation of substance isomorphic with an originating image, [for] virtual representations … analogy exists as a function of spatial recognition, of course, but it has loosed its anchors from both substance and indexicality[2]

As we continue to think through the impact of the digital on film and, as Rodowick has elaborated, on the history of aesthetics, it is important to acknowledge earlier incursions and interruptions into analogical representation facilitated by the photographic arts and during the period of their emergence. Leo Steinberg has eloquently described the result of Rodin’s multiplication of his sculptures:

If it occurs more than once, the sculptural form cannot be a direct representation of nature. It must be either an artifact in mechanical multiplication, or a thought obsessively thought again. It can be both. Only one thing it cannot be: the simple analogue of a natural body whose character is to be unrepeatable.[3]

Rodin’s sculpture asks what it means to be analogic by using one of the most analogical arts, an art that epitomizes “gravure” and by disrupting the singularity of the relationship between reality and representation its presence implies. This kind of sculpture cuts a fault line in the history of aesthetics by using a medium that relies upon an originating image while “displacing” the “simplicity” of its position as analogue. What is lost in this exchange becomes for Rodin a productive gain, perhaps neither an artifact of mechanical reproduction nor an image of thought, but a suggestion about the new found place for objects of modernity with a recognition of movement and the moving perception of the spectator’s eye.

It may be argued that the rise of photography itself inspired Rodin to fracture the analogic quality of his sculptures as the nature of his disdain for the photographic experiments of Muybridge and Marey, evident to his coterie of friends and acquaintances, suggests an insistence on movement and its impressions that escape photography. Rodin’s focus in his commentaries on photography upon what is lost in photography’s attempts to give singular, spatial representation to movement betrays his attenuation of and investment in the interval. In a conversation with Paul Gsell[4] , Rodin noted that there was “… no progressive development of movement [in photography] as there is in art … it is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies, for in reality time does not stop.” The fact that the photographs of his sculptures that Rodin commissioned from Eugene Druet in the 1890s begin to resemble the obsessive nature of Muybridge’s motion studies suggests Rodin’s recognition of the successive nature of sculpture, a recognition which is not necessarily inconsistent with his earlier critique of photographic motion studies. In the case of some of the photographs of Rodin’s work, each photograph reveals a sculpture’s change vis a vis the changing light and in others a sculpture is revealed through a succession of photographs displaying it from slightly different camera angles, see Figure 1). The simultaneous construction and deconstruction of movement accomplished by the fragments of chronophotography is consistent with Rodin’s acceptance and recognition within his work of sculpture’s existence as a whole comprised of recollected but disparate views from various angles. Rodin does what photography for him fails to do, capture time that does not stop, though this is also the initial ambition of Muybridge, Leland Stanford and Marey, who supplement the arrested image with attempts to capture moments of movement to which the camera remains untruthful.

Figure 2. The Three Shades, Auguste Rodin. This sculpture is comprised of three reproductions of the same original sculpture; Rodin reproduced it in Miniature to place atop The Gates of Hell.

Figure 3. The Gates of Hell, Auguste Rodin. Photographed by Eugene Druet, gelatin print, 1889.

Figure 4. The Gates of Hell, Auguste Rodin pictured with his wife, at a later stage in the completion of the sculpture.

Rodin disdained the scientific nature of photography because he determined that it usurped much of the creative role of the artist but beyond this disdain, there is a keen observation on the representation of movement that describes exactly how Rodin went about denaturing the analogical quality of sculpture. I would like to focus here on the inclusion in Rodin’s work itself of the act of perception and idea, an act which Steinberg gestures to in suggesting that Rodin’s “multiples” could be artifacts of “a thought, obsessively thought again.” We see particularly in The Three Shades that Rodin appears to be walking us through a process of perceiving a single figure, a process produced or set in motion by the work contained within the work itself (see Figure 2). Works like The Three Shades represent and acknowledge within the work the process of apprehension, that is, the multiplicity of perspectives permitted the spectator of a sculpture as well as the differences in how light, at various times of day or placed in differing spatial positions, changes the work. The various photographs Rodin commissioned from Eugene Druet, Jacques Erneste Bulloz and others of his sculptures at different moments of completion also acknowledge as discrete parts the moments of the process of the work’s production, which serve to fragment the sculpture as a whole as they simultaneously inscribe process within the work even as they spread “the work” over several instances of it which comprise a veritable journey. In the case of The Three Shades the means of apprehension is suggested within the object of apprehension and in the case of the photographs of the stages of creation the artist’s process becomes part of the work in its multiple instances. As Hélène Pinet notes in her investigations into Rodin and photography, “[t]he photographs reveal … a series of fleeting moments, transitory stages in the creative process that were destroyed in the very process of creating the work. For example, it is only in photographs that one can see the wooden armature of the Gates of Hell before it was completely covered with plaster statuettes …”[5] (see Figure 4)

|

|

| Figure 6. Fugit Amor, Auguste Rodin. | Figure 7. The Gates of Hell, close-up of Fugit Amor incorporated into the larger sculpture. |

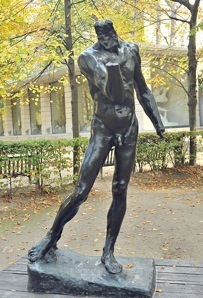

Figure 5. Prodigal Son, Auguste Rodin (reproduced as part of Fugit Amor and The Gates of Hell).

In the case of The Three Shades, the whole becomes the part, a relationship that also describes those works that contain other works as their parts, like Fugit Amor which contains Prodigal Son, or The Gates of Hell in which we find miniaturizations of a number of Rodin’s sculptures including Fugit Amor and The Three Shades (see Figures 2, 3, 5-7). A similar mise en abyme is encountered in Rodin’s propensity to depict figures falling, precariously balanced or leaning upon invisible space, in each case denying the viewer the traditional certainty of the ground (see Figure Volante (1890) and The Illusion of the sister of Icarus (1895) (Figures 10 and 11)), challenging us to conceive and to re-conceive the space surrounding the sculpture. In order to understand these figures, Rodin places the viewer in the position of Baudelaire’s flaneur trying to locate an eternal form from his collection of contingent particulars. As the flaneur attempts to situate himself in relation to a modernity increasingly characterized by Baudelaire as “ephemeral, fugitive, contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable,” so Rodin’s viewer attempts situating herself in relation to these figures which betray no ground from which to start and, through this receding origin and their future in multiplicity, without a sure place to end her contemplation and relation. In fact, Baudelaire depicts the result of neglecting the fugitive and transitory element of modernity, as a “… tumble into the abyss of an abstract and indeterminate beauty, like that of the first woman before the fall of man.”[6] Modernity might also be conceived of by Baudelaire’s logic as a happy Fall for man. The eternal that opposes the indeterminacy of beauty before knowledge is here found in the mundane details denoted by naming, the separations inaugurated by man’s exile from Eden, a location in the details of the profane marked ironically like the “tumble into abstraction” by the displaced nature of the Fall.

|

|

| Figure 10. Figure Volante, Auguste Rodin, 1890. | Figure 11. The Illusion of the sister of Icarus, Auguste Rodin, 1895. |

Steinberg remarks that Rodin’s “intuition is of sculptural form in suspension. He finds bodies that coast and roll as if on air currents, that stay up like the moon, or bunch and disband under gravitational pressure.” The musical fluidity of the implied movements of these sculptures as well as what Steinberg notes as their “evasive relationship to a supporting ground,” suggest Rodin’s concern with loss, with the potentials of bodies which (as is the case with all sculpture) must be approached by the spectator through the assembly and reassembling of fragmentary angles and lights from which they may be alternatively seen (angles and lights whose multiplicity are acknowledged within the work of sculptures like The Three Shades, or even in his re-contextualisations of sculptures like Prodigal Son which eventually ends up in Fugit Amor). The evasion of the ground and the explicitness of the reproductions acknowledge this truth about the temporal and divisive life of the spatialised whole of sculpture. Such re-contextualisations of sculptures like Prodigal Son not only admit the variety of angles and points of visibility, which together comprise a sculpture’s apprehension (as well as spreading the presence of the sculpture out over the course of its past and present incarnations), but also imply the selective process of illumination of the cinematic close-up and the suggestive process of the wide-angle. The kinds of photographs Rodin commissioned of his work early on, particularly those of Eugene Druet, which pay careful attention to capturing a work from a number of different angles, are a fundamental challenge to the notion that the mobile frame is particular to film. These photographs acknowledge the mobility of framing as part and parcel to the presence of sculpture; a mobile perspective is enacted within those sculptures which consist of multiplied figures while Druet’s photographs point out this mobility as a condition of the way in which sculpture is received.

It is the “impression of movement” which Rodin considers lacking in the “scientific” photographs of his contemporaries that he seeks to incorporate into his works. But what does it mean to incorporate such impressions into the work, especially as the multiples that deny his sculpture’s analogic qualities often resemble the successive photographs of the scientific imagists he criticized? This question may best be answered by turning to the relationship between part and whole in Rodin’s work. As Steinberg goes on to argue, “Of portrait busts it had always been understood that they were not decapitations; not commemorative of beheaded men, but a pars pro toto, the representation of a part signifying the whole. Rodin’s work demanded the extension of this simple logic to any anatomical cluster – and more than that: not a part for the whole, but the part as a whole, and its wholeness wholly immanent in the fragment.”[7]

I will later think about Rodin’s dynamic use of parts in relation to Deren’s film theory which was heavily influenced by Thomas Ernest Hulme and via Hulme, by Henri Bergson, but for now I would like to concentrate on how the inversion of classical representational signification Steinberg points to relates to Rodin’s attitude toward and later use of photography. To assign the “immanence” of the whole to the fragment is also suggestive of the place of the work in the world where signification is replaced by participation. I have discussed how this is evident in Rodin’s incorporation of the process of a sculpture’s creation (its physical construction and visual reception) within the work itself, a relationship between representation and reality that acknowledges the work as entangled with the reality it represents. Coincidentally, the indexical processes of photography’s capture of light places it in a similar position to Rodin’s sculpture; the part represented by the photographed moment participates in the whole of the reality it represents, standing at once apart from and within that whole. The nature of this mise en abyme implies a chase, a chase for a fugitive reality that is always at once within and beyond representation, but Rodin’s work begets a measure of praise for what occurs in the intervals of loss, the profusion of creative assemblages unique to the spectator which leaves Rodin’s work essentially unfinished, a whole reduced to the provisional arrangement of its parts.

We could perhaps conceive of this as provisional and the proliferations of encounters with a sculpture made possible by its reproduction in the context of Mary Ann Doane’s observation that the realm of chance opened by the photograph (that could picture anything at anytime) acted as a cathexis to a period when time is thought rather than felt.[8]

In her 1954 essay “Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality”[9] Maya Deren provides a response to the concerns about the artistic abilities of film whose very technology subjected it to the doubts raised by Rodin about the scientific image. I would like to suggest that her response mirrors Rodin’s meditations on reproduction in its utilization of the relationship between part and whole and in its recognition within the analogic whole of the creative as part and process. Early in the essay, Deren states that “[a]s we watch a film, the continuous act of recognition in which we are involved is like a strip of memory unrolling beneath the images of the film itself to form the invisible underlayer of an implicit double exposure …” Recognizing that film depends upon the various apprehensions of the spectator and that this process of apprehension looped through memory goes on to comprise the film’s presence, she later posits, “The images with which the camera provides [the artist] are like fragments of a permanent, incorruptible memory; their individual reality is in no way dependent upon their sequence in actuality and they can be assembled to compose any of several statements. In film … invention and creation consist primarily of a new relationship between known parts.” By Deren’s logic, the recognition that the whole of a film is comprised of parts, images which can and do exist independently, is the moment which permits the creative intervention of the artist. The part introduces as an aspect of the whole film the processes in which it participates, the apprehension of the spectator and the craft of the filmmaker. In this way, film accomplishes for Deren a situation that resembles Rodin’s sculpture and its fragmentations and multiplications, recognizing the unavoidability of incorporating process into the work in a way that acknowledges it as participant in the reality it signifies. In both cases, the linear narrative of analogy that characterizes photography and sculpture, is cleaved and then cleaved again.

Figure 14. Ritual in Transfigured Time. It is unclear whether this image of a sculpturally posed dancer is still or moving.

The sculpture garden sequence in Maya Deren’s Ritual in Transfigured Time consists of two major oppositions between the simultaneous and the successive; the dancer’s body and the sculpture on the one hand and the still image and the moving on the other.[10] At a number of points, Deren surprises her viewer by conflating the moving with the still, as when we are presented with an image shot with a still camera of a sculpture of the three graces and take it to be an unmoving image (Deren’s experiments earlier in the film with slowing and altogether halting the image help create this assumption). It is only at the point when the young girl suddenly enters the frame that we learn our assumption about the previous image as still rather than moving was potentially incorrect (see Figures 12-13 or click below for clip from Ritual in Transfigured Time). Similarly, it is unclear when the male dancer who climbs atop a pedestal and holds a pose as still as if he were a sculpture is simply holding this pose or whether Deren is again presenting us with a single, still image (see Figure 14 or click below for clip from Ritual in Transfigured Time). In discussing these two moments, I would first like to think through what it means for Deren to use the analogic qualities of film and photography to create uncertainty. It is useful here to think about Deren’s appeal to Gestalt psychology in her film essay “An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film”[11] when she writes that “[t]he creative work of art is an ‘emergent whole’ … in which the parts are so dynamically related as to produce something new which is unpredictable from a knowledge of the parts.” The uncertain moment Deren produces for her spectator attends to the unpredictability of the relation of the parts which comprise the film, on the level of the photograms and the images they contain and the relations between both of which Deren makes us especially aware.

Both Rodin and Deren experiment with creating works that present their own making, that is, works which explicitly reveal rather than efface their processes of creation. Those processes are twofold. First, the process of artistic creation evident in Rodin’s commissioning of photographs of the various stages of his sculptures and arguably in the figures with absent appendages like hands, head or arms (as in Figure Volante or the second Pierre de Wissant, whose hands have been removed) as well as in Maya Deren’s editing manipulations, her slowing and speeding up of time in her film. Second, the process of reception contained within the work is perhaps the more interesting for understanding the relationship between photography, film, sculpture and the body. This process is evident in the reproduction of the same figure in The Three Shades where we find the possibilities for the viewer’s reception to comprise the work as a whole. The inscription or implication of a process of reception (and re-reception) is most evident as it commissions the participation of the viewer’s own body in Rodin’s falling figures. In the absence of an establishing ground, as I have pointed out, these pieces call upon the viewer to attend to the work based on the orientation of the body it represents, a task that inevitably relies upon the interpretation of the viewer’s own body, its limits and experience. Similarly, Deren’s film acknowledges reception by making the spectator conscious of her own watching by surprising her (Rodin’s sculpture’s appeal to variations on perspective arguably brings about the same awareness of subjectivity on the part of the spectator), the film showcases its reliance upon the spectator’s expectations and attention to detail. (Is the man holding still or is this a still image?) Like Rodin’s falling sculptures, Deren’s work similarly commissions the bodily knowledge of the viewer. To distinguish between the still and the moving, the human and the sculptural in Ritual in Transfigured Time the viewer must draw upon her own familiarity with falling, dancing, with keeping still. It is through gauging the image according to her own bodily experience of the world that the viewer is able to discern that the figure of the faun holding still is really a photographic image and that the slowness with which he is able to fall to the ground defies gravity, indicating Deren’s manipulation of the frames her camera records per second. In these instances of falling bodies and in their acknowledgement and inscription within the art work of the process of the viewer’s apprehension, Rodin and Deren posit the “carnal third term” Vivian Sobchack calls for in her book, Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and the Moving Image Culture. Sobchack writes:

… we need to alter the binary and bifurcated structures of the film experience suggested by previous formulations and, instead, posit the film viewer’s body as a carnal “third term” that grounds and mediates experience and language, subjective vision and objective image – both differentiating and unifying them in reversible (or chiasmatic) processes of perception and expression.[12]

Figure 8. Pierre de Wissant, Auguste Rodin, 1886.

Figure 9. Pierre de Wissant, Auguste Rodin, 1900.

The impact of the photographic image and its employment in motion studies on Rodin’s sculpture generated a relationship between sculptural bodies and their viewers which acknowledged this “third term”, a position in which the spectator is forced to engage the sculpture as part of a “reversible process” wherein she at once perceives the work while expressing her own bodily orientation towards it (be it her angle of perspective or her understanding of what it feels like to fall). Rodin’s creation of such a bodily “third term” implies a similar place at film’s very inception for its spectator. It is no wonder that Deren is able so successfully to make manifest the participation of the spectator’s bodily senses by appealing at once to film’s relationship with its prototype, the photograph, and to sculpture whose mobile framing opposes the singularity of the photographic frame.

Returning to the relationship between part and whole, a relationship upon which Deren and Rodin concentrate in their work, the “whole” of Rodin’s sculpture and Deren’s film, come to consist of parts which, for all their apparent coherence, attest to the moment, or the presence of the work, which cannot be grasped, the frame missed by our eye’s slow perception (conveniently repeated for us in the still moments of Ritual in Transfigured Time, a repetition which ironically serves to remind us of the singular frame in opposition to the multiple and the possibility of our having missed it). It is the motion to which Muybridge’s image was untrue for Rodin because it stopped time, the elusive interval between two points on the flight of Zeno’s arrow which find as their counterparts in Rodin’s work the unacknowledged angle or height (or series thereof) from which a sculpture may be apprehended (photographed), or the presence afforded to it by the light at an unrecorded, unacknowledged split second of the day. The irony of Deren’s slowing down of the time of her film so that the viewer can better appreciate every angle and posture of the dancer’s body in motion is similar to the irony that comes of Rodin’s recastings as well as the prolific photographs he commissioned, each of which admit a slightly altered possible presence for the works. In both cases, the attempt to render a more complete vision to the spectator and thereby a more complete existence for the work ends up paradoxically attending to what is lost, what makes the work resist completion.

By building identification between the dancer’s body and the sculptures in this scene and by making sculpture a central object in negotiating the perceptual similarities and differences of photography and film, Deren recognizes something temporal in sculpture. It is our expectation that sculptures do not move (or at least not in so brief a time) that is forced upon us to realize. We think of the sculpture in Ritual in Transfigured Time and are forced to attend to it in terms of change and duration (components of movement and succession) rather than in terms of space. If we think back to the flaneur-like relationship that I have argued occurs for the viewer of Rodin’s falling sculptures, and the aspect latent in all of his sculptures potentially re-emerging changed in scale or repeated out of context, Deren’s interest in the relationship between part and whole, here situated at the site of the body, in sculpture and in film, begins to make sense in the context of the function of the body in relation to the transitory nature of modernity. Henri Bergson’s notion in Matter and Memory that movement is a translation in space of parts that qualitatively change the whole state that they comprise is obviously resonant with Deren’s Hulme-inspired observations about the nature of film and film-spectatorship.

What I would like to focus on in turning to Bergson at this moment is the role of the body in relation to movement imagined by Bergson and Deren. Bergson conceives of the impossibility of the instantaneous on account of the memory which pervades every moment of a person’s perception, this finds its counterpart in Deren’s conception of the reel of the spectator’s memory (a reel that I would like to encourage us to imagine in as many permutations permitted by distraction). Deleuze’s observation that Bergsonian duration is less marked by succession than by coexistence certainly extends to Deren’s own theory of cinematography and Mary Ann Doane’s observation that this is a co-existence seated in the “physiology and optical theory” which operate at the site of the human body. It is also commensurate with Deren’s imagination of the film event co-authored between filmmaker and spectator via recognition. I would like to conclude by exploring the extent to which Deren’s employment of the human form, the dancer and the sculpture, both as forms of beauty, encourage a relational and situational participation on the part of the spectator.

We are drawn to engage with the image of the male dancer through relating to his physicality and Deren procures this act of relation by permitting him to defy gravity, reminding us of our own spatial, earthly limitations. Here, we find ourselves negotiating a relationship with the dancer just as we struggle to determine the materiality of the object we study, whether it is indeed a still or a moving picture. The spectator finds herself in a saturated space of coexistence (the still beside the moving, the human beside the sculpture, the spectator beside the dancer) ironically measured by the transitory, fleeting nature of dance and film. Rodin’s falling sculptures themselves embody this coexistence of the moving within the still. But they also locate, in acknowledging the durational apprehension of the spectator (the co-construction of a sculpture from a combined series of memories), a similar coexistence within the body, that is the memory and perception of the spectator suggested by Bergsonian duration. In both Deren and Rodin we find two coexistences, the Bergsonian coexistence of memory and perception and a spatial coexistence in which the viewer, like Baudelaire’s flaneur with respect to modernity’s emblematic crowd, at once loses himself in the object (without the certainty of ground in Rodin’s case and without the certainty of the still or moving image in Deren’s) and is asked to pursue a potentially endless process of figuring in relation to the space and presence of his own body.

Of course, this only begs us to ask whether this is how sculpture should be apprehended beyond the film, revealing a truth that 18th century aesthetic distinctions between the arts have resisted. If this is the case, we find Deren, who always aligned herself with theorists invested in distinguishing the specificity of the medium of film, building a case for its difference from the other arts (and therefore an art in its own right rather than a “mongrel” medium) conflating two components of the central dichotomy upon which medium specificity has historically rested. In so doing, Deren constructs on a theoretical level the excesses that characterize her theories of creation, of adding to the “sum total of the world” rather than merely repeating it through representation. In this instance, the dynamic encounter between two aspects of aesthetics changes the way we understand our relationship to a classical and to a contemporary medium united in their oversimplification as analogical arts.

Endnotes

[1] Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Laokoon oder Üer die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie, translated as Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry.

[2] David Rodowick, Reading the Figural, or, Philosophy After the New Media (Duke University Press, 2001), p. 35-6.

[3]Leo Steinberg,Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth Century Art (Oxford University Press, 1972), p. 358.

[4] See Rodin On Art and Artists: Conversation with Paul Gsell, available at http://books.google.com.au/books?id=6rHq2uywRDkC&dq=isbn:0486244873.

[5] Hélène Pinet, “Montrer Est La Question Vitale: Rodin and Photography”, in Geraldine A Johnson (ed.), Sculpture and Photography: Envisioning the Third Dimension (Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 74.

[6] Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays (Translated and edited by Jonathon Mayne, Phaidon Press, 1964), p. 43.

[7] Steinberg, ibid., p. 370.

[8] See Mary Ann Doane’s Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive (Harvard University Press, 2002).

[9] See Leo Baudry and Marshall Cohen (ed.), Film Theory and Criticism (Oxford University Press, 2004).

[10] See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHnfpTW2P1U.

[11] See Bill Nichols (ed.), Maya Deren and the American Avant-garde (University of California Press, 2001).

[12]Vivian Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (University of California Press, 2004), p. 60.

Created on: Sunday, 7 November 2010