On February 3, 2004, the First Channel of Televisión Española (TVE) broadcast Memoria de España (Spanish Memory), one of its most recent and successful historical documentary productions,[1] to a great audience (4.6 million of viewers and 23.6% share). With the start of this series of twenty-seven episodes, the Spanish public channel, officially inaugurated in 1956, celebrated the fortieth anniversary of the broadcast of its first retrospective program: Testimonio (Testimony, 1964-1969).

The interest shown by Televisión Española in this genre over these forty years ? during which the television company has produced more than fifty historical documentary series of importance ? has not been matched by sufficient attention by academics and researchers. Indeed, the history of Spanish historical television documentary ? mostly written by TVE due to its many years of monopoly (1956-1982),[2] as well as to its greater economic, technical and human resources ? does not completely and systematically appear in any research thus far. Quite the opposite: the references to the productions mentioned above are scattered across sources such as the weekly magazine Tele-Radio,[3] a few books on the history of television in Spain,[4] the yearbooks edited by the public television and the Gabinete de Estudios de la Comunicación Audiovisual (Cabinet for the Study of Audiovisual Communication), GECA, and more recently, news articles.

This paper does not intend to describe all the retrospective series produced by Televisión Española between the first series, Testimonio, and the recent Memoria de España. The aim of this article is mainly to underline the relevance and evolution of the historical television documentary in Spanish television, by examining some of the series that have contributed the most to its consolidation in the public channel. The selection of these series has been based on the analysis of the programs and the review of the aforementioned bibliographic sources. At the same time, other criteria included for this purpose were, in some cases, the audience and critical success and, in some others, the contributions made to this television genre in Spain.

Testimonio: a pioneer program

The First Channel of Televisión Española began the broadcast of historical documentaries in 1964. Those documentaries were part of the program Testimonio, written and directed by the journalist and writer Ricardo Fernández de Latorre. Consistent with the pro-Franco conception of public television as an informative, cultural and educative organisation in the service of the regime, this program, like most historical documentary series produced by TVE during the 1960s and 1970s ? the last years of Franco ? sought to present to Spaniards some of the highlights of Spain’s contemporary history.

Testimonio opened on April 26 with the pilot episode “Cuando el aire era aventura. Vuelo Madrid-Manila” (“When the air was an adventure. Madrid-Manila Flight”) which sets up the main features and style of the series. First of all, it is worth mentioning the historical philosophy through which, according to its creators, the program should develop and which were, according to Mariano Roldán, the best expression the program could find:

The retrospective focus of the subjects is a constant theme in this program. In other words, it is not as much an attempt to bear witness to a present reality but to some facts of the past that, in a certain way, determined and became this present. The news, the graphic image of this past, becomes alive on the subject of a past history which we watch develop again before our eyes, led by the same characters who wove its plot.[5]

Figure 1: Fernández de Latorre checking archive material.

Source: Tele-Radio.

On the other hand, from the very beginning Fernández de Latorre used traditional narrative resources corresponding to this genre in television. All its one-hour-long episodes presented a generous amount of cinematographic and photographic documents commented by a voice-over, complimented with the shooting of some scenes to counterbalance the absence of archive material, and alternated with interviews with the main figures and witnesses to the events evoked.

The regular broadcast of Testimonio started in November of that year, although during this first season on the air, the program did not have a regularly scheduled timeslot. Each stand-alone episode was broadcast on the occasion of the anniversary or commemoration of some event. Among them, the most outstanding are the episode dedicated to Juan de la Cierva, inventor of the autogiro; “Los años heroicos del cine español” (“The heroic years of Spanish cinema”), a portrait in two chapters of the origins of the Spanish film industry, and the series of three episodes about the Madrid of the twenties, which gave an overall vision of the politics, the art and the bullfighting and sports life of the capital of Spain during those years which went down in history as “the happy twenties”. [6]

From the 1965-1966 season, due to the success achieved, Testimonio won a steady position in program planning with three monthly episodes, on Thursdays at 10.45 p.m. This frequency, which remained with few exceptions until the end of its broadcast, at the beginning of 1969, allowed its authors to introduce an important innovation at this stage: the serial character of many of its programs. Until that moment, serialisation had been used rarely, but later on, it became an essential feature of Spanish historical television documentaries. Thus, during its long presence on the screen, the Fernández de Latorre’s program reviewed in two or more episodes diverse national subjects, such as the immediate history of cities like Madrid, Barcelona, Málaga, Zaragoza, Valencia or Sevilla, the history of Spanish aviation, or the first film reporters in this country.

Therefore, Ricardo Fernández de Latorre set in Testimonio a classic pattern for Spanish historical television documentary: one that attaches a great importance to use of archive footage commented on by a voice-over and the selection of first-hand testimony from eyewitnesses and survivors; to give relevance to national subjects and to program the retrospective documentaries in series in order to tackle the complexity of the topics and develop audience loyalty. Fernández de Latorre, the pioneer of this genre in Spain used these formal and content elements in the rest of the historical documentary series produced by himself for Televisión Española: Treinta años de historia (Thirty Years of History, 1968-1969), El mundo de la posguerra (The Post-war World, 1969), España Siglo XX (Spain Twentieth Century, 1970-1973) and Ayer y hoy de la aviación española (Past and Present of Spanish Aviation, 1985-1987).

España Siglo XX, the longest series

The success of Testimonio during the ‘60s led Fernández de Latorre, at the beginning of the ‘70s, to become involved in the production of his most ambitious historical documentary series about the recent history of Spain: España Siglo XX. With almost 150 episodes, broadcast between February 1970 and July 1973, this series reviewed ? as the magazine Tele-Radio explained before its opening in Televisión Española ? Spanish life through all the seventy years of that century which had passed:

‘España Siglo XX’ is something more than the reflection of the history of our country throughout this century […]. What TVE prepares intensely and conscientiously from quite a lot of time is a review of the Spanish life from 1895 to present times. And the life of a country is something more than its history and is something more than a succession of data, time and names. What the Spanish audience will watch in this program is, neither more nor less, the heartbeat of the country. TVE will bring to the small screen the heart of Spain.[7]

Figure 2: Shot of España Siglo XX, which shows a moment of the meeting of the Spanish King Alfonso XIII and the President of French Republic, Poincaré, in Paris at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Source: Tele-Radio.

In order to convey to Spanish viewers a sense of national history – in accordance the desires of Franco’s regime – and to deal with such diverse aspects as history, politics, arts, sports, fashion and entertainment of those decades, the program was divided into three main blocks of approximately fifty episodes each, which, according to plans, where going to be tackled by the same number of producers: Ricardo Fernández de Latorre himself, Ricardo Blasco Laguna and Esteban Madruga. However, España Siglo XX was finally broadcast in two stages, whose episodes were completed by the two first producers. The fifty-two episodes of the first part had José María Pemán as scriptwriter. They narrated events in Spain from the loss of the last overseas colonies in 1895 up to 1918.[8] The ninety-two episodes of the second part were written by Eugenio Montes and covered the years between the end of the First World War and the year of the broadcast of the series.

Because the second part narrated the contemporary history written by the government in those days, its episodes showed, according to Baget Herms “the definitive ideologisation of the program toward very specific contents which gave a distorted or moderate vision of the historical facts”.[9] However, in spite of this fact, España Siglo XX was one of the first Spanish historical television documentaries to attract a popular audience through the classic combination of archive footage, music and voice-over comments. The key of its success – aside from the fact that it was broadcast in prime time – was that it broke up historical events into accessible-story lines and presented thousands of interesting and unknown archival images, which aroused the curiosity of Spanish viewers young and old.

The unprecedented success of España Siglo XX not only was evident in its long period of broadcast – which has never been equalled in the history of the historical documentary series produced by a Spanish television – but also in the favourable critical response it received, which included the Ondas Award for the Best Cultural Program in 1972. Due to that success, Ricardo Fernández de Latorre and José María Pemán published a weekly pull-out section in the magazine Tele-Radio for the followers of España Siglo XX, which summarised the history narrated audiovisually in each episode of the series in a print version.

La víspera de nuestro tiempo: the history of the Second Channel begins

November 15, 1966 saw the inauguration of a second channel of Televisión Española. From the beginning, the greater cultural interest of this channel motivated it (taking advantage of its minority character, which also provided a higher degree of creative freedom to the producers) to produce works with a more cinematic quality and greater depth. The cultural programming of the Second Channel of Televisión Española also included, of course, the historical documentary series, which at the end of the ‘60s were encouraged by same intention to construct a stronger sense of Spanish national identity as those of the First Channel. According to the channel’s promoter, Salvador Pons, this objective adapted perfectly to the project of the new channel:

In the Second Channel, we had the intention to dig deep in the cultural roots of our country, seeking for the signs of identity in landscapes, cities, history and literature that were our own. [10]

On April 21, 1967, five months after the official opening of its own programming, the Second Channel started to broadcast the biographical series La víspera de nuestro tiempo (“Our time’s eve”) with the episode “Barcelona y el modernismo” (“Barcelona and modernism”) which evoked the activities of Pablo Picasso, Casals and Gaudí in Barcelona at the beginning of the past century.[11] Although it began to broadcast bimonthly, this program was never subject to inflexible broadcast and production schemes. On some occasions, three weeks passed without an episode and, in other periods, the program had a weekly frequency.

The main idea of this series, directed by the film writer and director Jesús Fernández Santos, was suggested by Salvador Pons and, according to Baget Herms, it sought:

to present the different Spanish authors in relation with their geographic and human environment. They were mostly thinking about the XIXth century writers – hence the title of the program – but later on this concept was extended little by little and freed up to include the classics. On the other hand, in addition to a focus on story tellers or novelists, the program included episodes devoted to essayists (D’Ors), musicians (Joaquín Rodrigo y Aranjuez) or other general topics (“Los toros en la literatura” [“Bulls in Literature”] or “Los escritores y el mar” [“Writers and the sea”]) and even non-Spanish authors, as long as they were clearly closely bound to the country, such as Ernest Hemingway.[12]

The majority of the artistic and literary creation of the aforementioned authors was based around landscape. Therefore, in order to achieve the more than thirty biographies that the series finally included, La víspera de nuestro tiempo not only used photographs and archive film of the characters portrayed, but also location shooting of the cities that those artists captured in a concert, a canvas or the pages of a literary creation. Moreover, in the case of the writers, together with the voice-over narration of their lives and the background music, these shots were often accompanied by the reading of some of the texts that they dedicated to those landscapes.

Figure 3: Jesús Fernández Santos, director of La víspera de nuestro tiempo.

Following the rules of the Second Channel in those first years, the different episodes were commissioned to producers and writers who, for different reasons, had shown more affinity with the characters. Even Fernández Santos took the camera to direct some programs, such as “Elogio y nostalgia de Toledo” (“Praise and nostalgia of Toledo”), which won the first award in the II Film and Television-Narration International Festival, hosted in Alghero (Sardinia) in 1969. Furthermore, La víspera de nuestro tiempo was the first Spanish cultural program to be sold to other channels abroad, more specifically to French television and the Italian RAI.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the Second Channel of Televisión Española shared with the First Channel the production and programming of more important historical documentary series. However, since the ‘90s, the minority character of this type of program and the strong competition for audience of the incipient private channels caused, with the few and interesting exceptions – Los años vividos (The Years Lived, 1992) and Memoria de España (2004-2005) – the disappearance of this historical genre in the First Channel’s program planning.[13]

History with hardly any archive film: La huella del hombre and La noche de los tiempos

In the 1970s, almost all the historical documentary series produced by Televisión Española were completed in the first half of the decade, because after the death of Franco and the beginning of the process of political transition in Spain at the end of 1975, the present started to interest Spaniards more than the past, and retrospective programs were replaced by news programs, including debates, and programs of interviews. With the exception of the aforementioned España Siglo XX, those series were distinguished by the inclusion of new narrative resources. One audiovisual innovation was the partial replacement of the predominant archive footage by other elements such as recent shots filmed on purpose for those programs, engravings, illustrations. Just as had happened in other countries, one of the reasons that led Spanish documentary makers to leave such traditional resources in the audiovisual history was, largely, the selection of distant periods for their historical television reports, which obviously could not be caught by cinematographic or photographic cameras. Thus, the historical documentary series produced by TVE continued with its informative-formative function and the Spanish viewers were able to know the deeds of humanity and their own ancestors from the images shown, which were sometimes narrated with a triumphalist tone.

Two of these innovative series, La huella del hombre (The Footprint of Man) and La noche de los tiempos (The Night of the Times) might be included as part of the analysis of Western civilisation initiated by the BBC series Civilisation (1969). The former (La huella…), which was broadcast by the First Channel of TVE during the 1969-1970 season, had that title because its aim was to capture the historical and cultural evolution of humanity from the moment mankind left his hand prints on the Altamira walls up to his giant leap on the surface of the Moon.[14] In order to achieve this, its producer, the journalist Octavio Cabezas, used still images ? photographs, maps and illustrations ? as well as moving images available from the archives of Televisión Española; and the extinct newsreel NO-DO ? a newsreel used by Franco’s regime as a political propaganda instrument from 1943, which disappeared officially in 1981 ? from the documentaries by the Ministries of Education and Sciences and Information and Tourism, from the archives of commercial distributors and embassy and museum collections. In addition, La huella del hombre also included countless shots filmed for the series from natural locations, which gathered remaining evidence that could better illustrate the steps forward throughout millions of years of the history of humanity.

Although the journalist Joaquín Vidal drew upon the technical advice of several specialists in each historic period tackled in order to write the scripts, they did not participate in the program on camera. Only the presenter, Rafael de Penagos, appeared on screen. However, unlike Kenneth Clark in Civilisation or Alistair Cooke and Jacob Bronowski in America (1972) and The Ascent of Man (1974), he did not appear in the same shot as archaeological evidence on location, but from a television set, either at the beginning of the episodes in order to introduce the subject, or during their development to complete the explanations given by a voice-over.

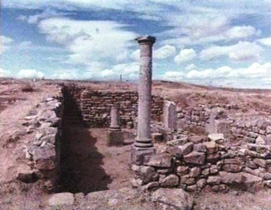

Figure 4: Shot of La noche de los tiempos, which shows signs of the Roman Empire in Iberian Peninsula.

On the other hand, La noche de los tiempos opened on August 5, 1971, also on the First Channel, produced by Jesús Fernández Santos, Juan García Atienza, José Antonio Páramo and José Luis Tafur. This series of fifty episodes which were broadcast until November 25, 1972 looked for the origins of a Spanish civilization, and told the course of the history of this nation from its origins on the Iberian Peninsula at the end of the Tertiary Period up to the date of the broadcast.[15]

Just as the team in charge of La huella del hombre had done, the producers of this new program supported the voice-over narration with images shot for the occasion right at the archaeological, artistic, as well as monumental sites that helped to explain the evolution of the Spanish people more graphically. However, unlike the former, La noche de los tiempos was shot in 35mm color stock. Due to its extraordinary quality, the program shared with España Siglo XX the Ondas Award for the Best Cultural Program in 1972; at the same time, it occupied an outstanding position – Saturday nights at 10.00 p.m. – within the Televisión Española’s program schedule.

Reconstructing history: Así fue

Also during the 1970s, probably due to the influence of the historical dramas that proliferated at the time in Televisión Española, the retrospective series produced by the public channel began to introduce another narrative resource ignored by them up until that moment, and which later, as the series Memoria de Españahas demonstrated, would become an important ingredient of Spanish television history: the re-enactment of events.

The first series that regularly used re-enactment, with actors, of events that could not be presented by the original historical people began on April 20, 1974, on the Second Channel under the title of Así fue (It Happened This Way). Directed by Enrique de las Casas, written by Juan Tébar, José Luis Monter and Jesús Yagüe, and produced alternatively or jointly by these last two, it was on the air on Saturday nights, from 9.00 to 9.30 p.m., until September 7 of that year.

The idea that initiated this historical series was to update certain specific dates that had not received the attention from historians it was felt they deserved, although, according to its authors, they had considerable repercussions in the national life of later years. In order to achieve this merger between journalism and recent history, the twenty episodes had a presenter who introduced the program. The days recalled were all of them part of the recent past of Spain, since, in addition to the dramatisations, those responsible for the production also wanted to draw on archive film and testimonies from interviews of the main figures as well as other characters who related to them.[16]

In this way, Así fue recalled, among others, the day in which the autogiro of Juan de la Cierva flew for the first time, the day in which Ramón y Cajal was awarded the Nobel Prize, the day in which the first sound movie opened in Spain, the day in which the Semíramis arrived, the day in which the production of the Seat 600 car began, the day in which the underground in Madrid was inaugurated, the day in which Spain defeated England in the World Cup of Maracaná, the day in which the Universal Exhibition of Barcelona opened, or the day of the first Iberia Airlines flight.

The presenter as conductor of the story: Memoria de España. Medio siglo de crisis

In the years right after the political transition in Spain – the 1980s – the aim of the main historical documentary series produced by Televisión Española was to narrate some of the more important events than they had taken place in Spain throughout the twentieth century, among which the Spanish Civil War found a privileged position. In this way, the public channel wanted to remember for Spaniards its more difficult history in order to give legitimacy to the democracy just recovered. One of the most representative series was Memoria de España. Medio siglo de crisis (Memory of Spain: Mid-Century of Crisis) saw the return to TVE of Ricardo Blasco Laguna, who, as has been already mentioned, narrated on-screen part of the Spanish contemporary history in the colossal series España Siglo XX. This new series aired in the First Channel between April 10 and September 11, 1983, and it captured in eighteen episodes the events which occurred between the so-called “Disaster of ‘98” and the Spanish Civil War.

In addition to the classical narrative resources used by Spanish television history (archive footage, photographs, color graphics, cartoons, newspapers and music from the time), Ricardo Blasco introduced presentations by the actor Fernando Rey on screen, in order to make accessible political, economical, social and cultural aspects that distinguished this crisis period in Spain. However, even though in La huella del hombre Rafael de Penagos appeared on a television set introducing the subject of the episode and alternating small interventions in order to replace the inevitable gaps between filmed material, in Memoria de España. Medio siglo de crisis, Fernando Rey as presenter served as the main device for narrative development in the documentaries, with ninety-two interventions – or in other words, three hours of program and more than five-hundred pages of text [17] – which were shot in the locations where the events had happened using a didactic tone. Such a prominence of a presenter has not been seen again in other historical documentary series produced by the public channel; however, this narrative resource continues to be used, with moderation, as recent titles as the mentioned later Mujeres en la historia (Women in History) demonstrate.

Los años vividos: the witnesses as main figures

Retrospective series which reviewed the most relevant events during the twentieth century in Spain also were evident at Televisión Española in the 1990s in order to summarise the century drew to a close. The most original and successful in TVE was Los años vividos, whose ten episodes were aired on the First Channel between January 19 and April 5, 1992, from 10.30 to 11.30 p.m.[18]

Directed and written by Mercedes Odina and produced by Pere Joan Ventura, Los años vividos offered a television tale of every day life, fashion, music and film tastes, but also the main historical, political and social references of Spanish history from 1920 to 1992. However, unlike other series, it did not present history as a treatise full of dates and information, but as a call to the memory of more than one hundred and fifty famous personalities of the politics, arts, culture, science or sports world. This way, although all the episodes were presented by Odina and the first two used voice-over profusely to frame testimonies and the images which illustrated them in a context, as well as to make the transitions from one thematic aspect to another; from the third episode onward, the omniscient comments disappeared completely to leave the interviewees totally in charge of the narration.

As has been already explained, testimony had already been widely used in many preceding Spanish historical documentaries; however, in Los años vividos it was given an original inflection as it used the concept of “generation” as the organising principal. Indeed, the witnesses were grouped by generations and they contributed, with their testimonies, to discussion of the decade in which they were twenty to thirty years old.[19] This was because, according to the director, it is during the young adult years that people get more involved in the historical moment they in which they live and become both active and passive subjects of the political, social and cultural circumstances of their time (although from the psychological perspective, the childhood and adolescent years are those that determine the individual’s character).

Finally, another innovation of this historical program, which raised great excitement and soon became one of its most emblematic elements, was the exceptional documentary picture that closed every episode. Each one of those pictures gathered in front of the camera the main figures of the different generations in representative places, such as the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid, La Moncloa or La Zarzuela. In many cases, these personalities had not seen each other for a long time or they simply served in very diverse and conflicting political sites, although they had shared some of the most important pages of the history of the twentieth century in Spain.

La Transición, the most international series

In the second half of the 1990s, historical documentary series produced by Televisión Española stood out as commemorations of several notable anniversaries at the end of the twentieth century. Among them it is undoubtedly worth mentioning La Transición (The Spanish Transition), a series of thirteen episodes that in 1995, on the occasion of the 59th anniversary of the National Uprising and the twenty years of reign of Don Juan Carlos I de Borbón, recalled the main political, economical, social and religious events of the first stage of the political transition in Spain (1973-1977)

Figure 5: Shot of La Transición, which shows a moment of the coronation ceremony of the current Spanish Monarchs after the death of Franco in 1975.

Directed by Elías Andrés and written and narrated by the journalist Victoria Prego, La Transición did not present any innovation regarding the narrative elements used, since, like many other previous Spanish retrospective television series, it used a predominant voice-over comment over a collection of archive film, among which the testimonies of some key personalities of the time were inserted.[20] Nevertheless, this program obtained high audience levels (during its first broadcast in the Second Channel, between July 23 and October 15, the audience average who watched this series exceeded two million viewers). In addition, this success was endorsed by favourable reception by Spanish historians and communication professionals – who conferred on Prego the Víctor de la Serna Award to the most outstanding journalistic work of 1995 – and by the sales of this series to the main foreign television channels and many European and Latin-American universities, which turned it into one of the most successful international historical documentary series ever produced by Televisión Española.

The reasons for the audience and critical success of La Transición are not only its careful production or the fact that was the first audiovisual effort to rescue the most significant images of the political process to democracy in Spain, by giving them a unitary and global cohesion; but also its purpose to update and legitimise, from a point of view of consensus, the experiences and collective decisions made by Spaniards in those difficult and significant years. As Josetxo Cerdán also says, La Transición made a television celebration of the Spanish process of political reform:

When this series arrives on the screens […] already it can be said that a desire exists to celebrate the transition. It is possible to conclude, therefore, that Spaniards have a desire to see themselves on TV in this historical moment which they have carried out and already given up as closed. The idea of to have lived and to have carried out a unique event has consolidated socially: it is time to begin to address that moment with suitable images and for that nothing is better than television. [21]

Mujeres en la historia, a classic of the Second Channel

In spite of the fact that the biographical series had been part of Spanish television history since the end of the 1960s, with titles as Biografía (Biography, 1967), La víspera de nuestro tiempo (Our Time’s Eve, 1968-1969), Abierto en el aire (Open in the Air, 1988), Testigos del siglo XX (Witnesses of the Twentieth Century, 1990) or Tres Grandes del Siglo de Oro (Three Great Figures of the Spanish Golden Century, 1991), until the end of the twentieth century, none of them had recovered the contribution of women to Spanish history.

On the evening of July 11, 1995, at 11.00 p.m., the journalist María Teresa Álvarez opened on the Second Channel, as director and presenter, the most recent historical documentary series produced by Televisión Española: Mujeres en la historia. In that opening season, which consisted of nine episodes of one hour each, this series unveiled the personality of the same number of women again who, in the director’s opinion, had great relevance in the history of Spain, but were as yet unknown by the general public: Leonor Plantagenet, María de Molina, Juana “La Beltraneja”, María Pacheco, Juana de Austria, sor María de Ágreda, María de Zayas, Isabel de Farnesio and Concepción Arenal. [22] In order to rescue them from oblivion, Álvarez tackled the historical moment in which they lived and the reality of women in the society of their times, by using illustrations and portraits of the biographical subjects, shots filmed in the locations which were more related to their lives – from which sometimes the journalist appeared historically framing some events – along with personal comments of historians, writers and archivists.

Although those programs concluded on September 12, Mujeres en la historia began a second season on June 13, 1998, at 8.00 p.m. In the ten episodes of this new season, Álvarez maintained the aim of salvaging from anonymity the free and independent women who, according to her, always fought to achieve what they wanted even under the most difficult circumstances, and who never yielded in the face of adversity of their time, even though history had turned away from them. Among the main figures were the countess-duchess of Benavente, the countess Eugenia de Montijo, Josefa Amar y Borbón, Leonor López de Córdoba, the princess of Éboli, Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda, Carolina Coronado, Robustiana Armiño, Beatriz Galindo, Isabel Roser, Teresa Cabarrús, Rosario de Acuña, the sisters María Rosa Rafols, Micaela Desmaisieres and Teresa Gallifa, and María Lejárraga. The season closed on September 5, that year.

Mujeres en la historia, which drew on the advice of the historian Carmen Iglesias during this new season, maintained its original format: using old documents preserved through the centuries, in order to unveil the personality and work of the aforementioned women; incorporating the thoughts of specialists; and some scenes shot in the countries where they lived. However, due to the lack of real material, some episodes added, although it was not part of the philosophy of the series, another narrative element: dramatisations.

The third season of Mujeres en la historia lasted from April 6 to May 4 2003. Directed, written and presented again by María Teresa Álvarez, the series maintained its essence and portrayed, in five episodes of one hour, the same number of women again who, as the previous twenty-five, had fought to occupy a significant position in the epoch in which they lived, although history had excluded them in one way or another. In order to achieve these television profiles, just as in the previous season, the program appealed to pictorial portraits and illustrations of the personalities, the presenter’s explanations, the comments of diverse historians and experts and the re-enactment of certain scenes in the places where the five Spanish women selected had lived: Cristina de Habsburgo-Lorena, Rosalía de Castro, Ana de Austria, Clara Campoamor and Carmen de Burgos “Colombine”.

Figure 6: Re-enactment of Mujeres en la historia, which shows the Spanish Queen Isabel la Católica in her deathbed.

Mujeres en la historia came back to the screens of Televisión Española on May 4, November 28 and December 5, 2004, with three special programs about the figures of three Spanish Queens: Isabel II, Isabel la Católica and her daughter Juana “La Loca”. These programs commemorated the first centennial of the death of the former, and the fifth centennial of the death of the second and the ascension to throne of the latter. Such was the duration of this series on the Second Channel for four seasons throughout a decade, it was regarded as a classic documentary by its viewers.

Memoria de España: history told with the latest technologies

Finally, Memoria de España – directed by Luis Martín del Olmo and co-ordinated by the historian Fernando García de Cortázar – was aired between February 2004 and March 2005. This series, which told the history of Spain from prehistory to nowadays (including the general elections on March 14, 2004, and the signing of the European Constitution), entails the most important commitment to historical documentary made by the public channel in recent years. Televisión Española’s interest in this genre was demonstrated, for example, by the fact that more than 200 professionals worked on this series – until then, most of Spanish television historical documentary series had been produced by small teams, composed by less than ten members – and after more than a decade, consigning the retrospective series to the minority Second Channel, the executives of TVE decided to broadcast its twenty-seven episodes in the First Channel, in prime time and without commercial breaks.

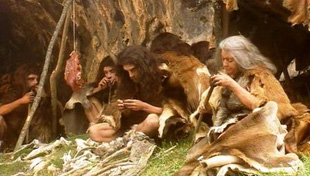

Figure 7: Re-enactment of Memoria de España, which shows the first inhabitants of Iberian Peninsula.

In its eagerness to reach the large audience, in the beginning of the Twenty- first century, the creators of Memoria de España “revolutionised” the traditional way to make historical documentaries in the public channel started, forty years before, with the pioneer Testimonio. Thus, they stopped using some classic narrative resources, such as the presenter and the eyewitnesses testimonies; they replaced them with other less frequent and new devices, such as the re-enactment of scenes with the most advanced infographic and 3D digital animation technologies, or the dramatisation of events, which illustrated the historical passages narrated by a voice-over in view of the lack of archive footage. [23]

In summary, this historical approximation to the historical television documentary series produced by Televisión Española – since its first program, Testimonio, to the recent great production Memoria de España – has proved the relevance and consolidation of this genre in the Spanish public channel – especially, in its Second Channel – throughout its fifty years. It has also showed the evolution of the narrative resources used in the production of its titles, from the traditional combination of archive material, voice-over comments and the talking heads testimonies to the re-enactment of events with actors and digital animation technologies. Besides, this brief historical journey through the Spanish television history has demonstrated the prominence of the history of Spain between the subject matter of the series produced by TVE, due to, in many cases, the intention of the public channel to configure the way of thinking the present of the Spaniards through the presentation of their own past.

Works Cited

S. Alegre, “La Transición española, un documental histórico”, Film-Historia, vol. X, no. 3, 2000, pp. 169-194.

J. Mª Baget Herms, Historia de la televisión en España 1956-1975, Feed-Back: Barcelona, 1993.

J. Mª Baget Herms, “El documental televisivo en España (y II)”, Imagen y Sonido, no. 62 (August 1968), pp. 44-46.

J. Cerdán, “Dos o tres conclusiones, desde el presente, sobre el binomio Televisión/Transición”. Área Abierta, no. 3 (July, 2002). www.ucm.es/info/cavp1/Area%20Abierta/AREA%20ABIERTA%203/articulos/cerdan.PDF

“De Altamira a la Luna. Tras ‘La huella del hombre’”, Tele-Radio, no. 615 (October 6 to 12, 1969), pp. 22-23.

E. F. M., “‘Así fue’. Historia de los días y los hombres”, Tele-Radio, no. 819 (September 3 to 9, 1973), pp. 16-17.

M. Escribano, “‘España Siglo XX’. Un programa que hace historia”, Tele-Radio, no. 634 (February 16 to 22, 1970), pp. 12-13.

“España Siglo XX. 75 años de historia”, Tele-Radio, no. 615 (October 6 to 12, 1969), pp. 10-11.

A. Fernández, “‘Memoria de España’. De la prehistoria a la democracia”, El Mundo del Siglo XXI, February 3, 2004, p. 52.

F. G. H., “‘Memoria de España. Medio siglo de crisis’”, Tele-Radio, no. 1.319 (April 8 to 14, 1983), p. 34.

S. Hernández Corchete, “Hacia una definición del documental de divulgación histórica”, Comunicación y Sociedad, vol. XVII, no. 2 (December 2004), pp. 89-123.

A. Javaloyes, “La víspera de nuestro tiempo. Literatura y paisaje”, Tele-Radio, no. 520 (December 11 to 17, 1967), pp. 16-19.

S. Mayoral, “Ajuste de cuentas con la Historia. La 2 estrena una serie dedicada a mujeres relevantes del pasado”, El Mundo del Siglo XXI, July 11, 1995, p. 61.

A. Pezuela, “Un espacio en busca de la España de ayer. La noche de los tiempos”, Tele-Radio, no. 713 (August 23 to 29, 1971), pp. 28-30.

S. Pons, “Paisajes de la historia”, El País, June 3, 1988, p. 32.

M. Roldán, “Testimonio”, Tele-Radio, no. 445 (July 4 to 10, 1966), pp. 10-19.

C. Savall, “‘Los años vividos’ gana el Ondas Internacional”, El Periódico de Catalunya, November 5, 1992, p. 56.

Endnotes

[1] This paper understands the historical documentary as “the speciality documentary in which the author addresses the general audience with the aim to reveal to them a set of past and worth remembering events, public as well as private, in a truthful and reliable manner. These preferably adopt a narrative and dramatic structure for their storytelling, in which a voice-over narrates the story as the images follow one another – archive film, photographs, works of art, maps, graphics, newspapers, present shots of historical sites and even the partial re-enactment of certain episodes – among which it is usual to insert the testimonies of the main figures involved or the explanations of experts on the matter or the approached period”. Sira Hernández Corchete, “Hacia una definición del documental de divulgación histórica”, Comunicación y Sociedad, vol. XVII, no. 2 (December 2004), p. 121.

[2] The monopoly of Televisión Española lasts from its origins to the appearance of the first regional channels in the mid 80’s, such as ETB1 (1982), TV3 (1984), TVG (1985) or ETB2 (1986), which were joined by Canal Sur, Telemadrid, C33 (it is divided between El 33 and K3 since 2001) and Canal 9 in 1989.

[3] In addition to the official Televisión Española’s program planning, this magazine, which was published between 1960 and 1986, included reports on the programs that the channel was about to air soon or on those that were already on the air.

[4] The works that have been reviewed mainly are: Juan Felipe Vila-San Juan, La “trastienda” de TVE (Plaza & Janés: Barcelona, 1981); Josep Maria Baget Herms, Historia de la televisión en España 1956-1975, (Feed-Back: Barcelona, 1993); Manuel Palacio, Historia de la televisión en España (Gedisa: Barcelona, 2001); Joan Munsó Cabús, La otra cara de la televisión. 45 años de historia y política audiovisual (Flor del Viento Editores: Barcelona, 2001); Manuel Palacio (ed.), Las cosas que hemos visto. 50 años y más de TVE (Instituto Oficial de Radio y Televisión: Madrid, 2006).

[5] The original Spanish text is: “El enfoque retrospectivo de los temas es una constante de este programa. Es decir, se trata de dar testimonio no tanto de una realidad presente como de unas realidades pasadas que de alguna forma determinaron y constituyeron este presente. La noticia, la imagen gráfica de ese pasado, cobra sustantividad al hilo de una historia pretérita que vemos desarrollarse ante nuestros ojos protagonizada por los mismos personajes que urdieron su trama”. Mariano Roldán, “Testimonio”, Tele-Radio, no. 445 (July 4 to 10, 1966), p. 11.

[6] Cfr. J. Mª Baget Herms, Historia de la televisión en España 1956-1975, op. cit., p. 141.

[7] The original Spanish text is: “España Siglo XX es algo más que un reflejo en imágenes de la historia de nuestra patria en lo que va de siglo […]. Lo que TVE prepara intensa y concienzudamente desde hace bastante tiempo es un repaso de la vida española desde 1895 a nuestros días. Y la vida de un país es algo más que su historia; es algo más que una sucesión de datos, fechas y nombres. Lo que el público español verá en su momento es, ni más ni menos, que el latir del país. TVE traslada a la pequeña pantalla el corazón de España”. “España Siglo XX. 75 años de historia”, Tele-Radio, no. 615 (October 6 to 12, 1969), p. 10.

[8] Cfr. Matías Escribano, “‘España Siglo XX’. Un programa que hace historia”, Tele-Radio, no. 634 (February 16 to 22, 1970), pp. 12-13.

[9] Cfr. J. Mª Baget Herms, Historia de la televisión en España 1956-1975, op. cit., p. 217.

[10] The original Spanish text is: “Nos preocupaba en aquella audaz empresa de la Segunda Cadena ahondar en las raíces culturales de nuestro país, buscando las señas de identidad en paisajes, ciudades, historia y literatura que nos fueran propios”. Salvador Pons, “Paisajes de la historia”, El País, June 3, 1988, p. 32.

[11] Cfr. Antonio Javaloyes, “La víspera de nuestro tiempo. Literatura y paisaje”, Tele-Radio, no. 520 (December 11 to 17, 1967), p. 16.

[12] The original Spanish text is: “Se trataba de dar a conocer a los distintos autores españoles en relación con su ambiente geográfico y humano. Se pensaba, ante todo, en los escritores del siglo XIX –de ahí el titulo de la emisión–, pero más tarde se fue ampliando o liberando este concepto, hasta llegar a los clásicos. Por otra parte, a los narradores o novelistas, se unieron programas dedicados a ensayistas (D’Ors), músicos (Joaquín Rodrigo y Aranjuez) o dedicados a temas genéricos (“Los toros en la literatura” o “Los escritores y el mar”) e incluso a autores no españoles, pero netamente vinculados al país, como Ernest Hemingway”. J. Mª Baget Herms, “El documental televisivo en España (y II)”, Imagen y Sonido, no. 62 (August 1968), p. 44.

[13] At the beginning of the 90’s, the appearance in Spain of the three private channels of national range, two of them with unscrambled broadcast (Antena 3 and Tele 5) and the other, a pay-television, Canal +, encrypted during the most significant part of its broadcast, but with many hours of unscrambled programming with a generalist character, meant the total liberalization of television in Spain and the definitive break-up of the monopoly of Televisión Española, which was initiated with the establishment of the first regional channels. With this new situation of competition, all the channels organized their programming strategies based on the privilege of programs aimed to a broad consumer, in such way, that in the case of TVE, the majority of historical documentary series were banished to the Second Channel and many others were moved away from prime time.

[14] Cfr. “De Altamira a la Luna. Tras ‘La huella del hombre’”, Tele-Radio, no. 615 (October 6 to 12, 1969), p. 23.

[15]Cfr. Alfonso Pezuela, “Un espacio en busca de la España de ayer. La noche de los tiempos”, Tele-Radio, no. 713 (August 23 to 29, 1971), p. 28.

[16] Cfr. E. F. M., “‘Así fue’. Historia de los días y los hombres”, Tele-Radio, no. 819 (September 3 to 9, 1973), pp. 16-17.

[17] Cfr. F. G. H., “‘Memoria de España. Medio siglo de crisis’”, Tele-Radio, no. 1.319 (April 8 to 14, 1983), p. 34.

[18] With an average audience of two million of viewers, this series won the International Ondas Award in 1992, which is awarded by the Spanish radio channel SER. Cfr. Cristina Savall, “‘Los años vividos’ gana el Ondas Internacional”, El Periódico de Catalunya, November 5, 1992, p. 56.

[19] Each decade had its own episode, with the exception of the 30’s, with the Spanish Civil War, and the 70’s, with the death of Franco, which were separated into two chapters due to their enormous density and to the chronological fact that a whole generation was immersed in the war struggle and a whole other in the construction of a democratic system.

[20] Cfr. Sergio Alegre, “La Transición española, un documental histórico”, Film-Historia, vol. X, no. 3, 2000, p. 169.

[21] The original Spanish text is: “Cuando dicha serie llega a las pantallas […] ya se puede constatar que existe un deseo de celebrar la Transición. Se puede concluir, por lo tanto, que los españoles tienen ganas de verse en la tele en ese momento histórico que han protagonizado y que ya dan por clausurado. La idea de haber vivido y protagonizado un acontecimiento único e irrepetible se ha consolidado socialmente: es hora de comenzar a vestir ese momento de las imágenes adecuadas y para ello nada mejor que la televisión”. Josetxo Cerdán, “Dos o tres conclusiones, desde el presente, sobre el binomio Televisión/Transición”. Área Abierta, no. 3 (July, 2002). http://www.ucm.es/info/cavp1/Area%20Abierta/AREA%20ABIERTA%203/articulos/cerdan.PDF.

[22] Cfr. Soledad Mayoral, “Ajuste de cuentas con la Historia. La 2 estrena una serie dedicada a mujeres relevantes del pasado”, El Mundo del Siglo XXI, July 11, 1995, p. 61.

[23] Cfr. Ángel Fernández, “‘Memoria de España’. De la prehistoria a la democracia”, El Mundo del Siglo XXI, February 3, 2004, p. 52.

Created on: Tuesday, 11 December 2007