Manny Farber: February 20, 1917 – August 17, 2008

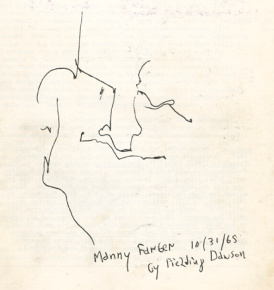

Manny Farber portrait by Fielding Dawson

Manny Farber changed the way film was written and thought about. He demonstrated new ways to approach cinema and shared with us new ways to see film. His influence on two generations of film critics has been profound (see the Screen-L selection of obituaries on their website for a hint of this).

Screening the Past has chosen to honor Farber in his own words. The following “interview” started, innocently enough, with a tape-recorded interview session, followed by making and editing a transcript, and sending it to Farber and Patricia Patterson. Then the fun began. Manny said we might make a few changes, get together next weekend? Of course. This went on for four months, getting together on weekends, working it over, and over. At the end of the four months, I’m not sure a single sentence from the original tape-recording survived without being revised, removed, or replaced. The addition of new material was constant. The result is hardly an interview, rather an ongoing dialogue written (and rewritten) by three authors. It appeared originally in Film Comment v. 13, n. 3, May-June 1977, pp. 36-45; 54-60. Not long after these sessions, Farber stopped writing film criticism (and I stopped doing interviews). Asked why, he told me “Writing film criticism is too hard.” He had a great dry deadpan and a taste for irony and ambiguity; one could never be quite sure when and how much he was kidding…

Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson Interviewed by Richard Thompson, 1977

In one of his baby pictures, Manny Farber has the costume and the face of The Yellow Kid; as he explained, “Our parents used to dress us in costumes from all the comic strips.” He has subsequently become a painter, carpenter, film critic, and teacher so overlappingly that they are one.

He wrote on films and art for The New Republic, replacing Otis Ferguson in 1942, until 1946; in 1949 he became Time’s film critic. He wrote about film for The Nation, 1949-1954; The New Leader, 1957-59; Cavalier, 1966; Artforum, 1967-71, among others. A collection of this material, Negative Space, appeared in 1971; the Da Capo Press Expanded Edition appeared in 1998. He has taught film and painting for the last ten years or so, first in New York, then at the University of California at San Diego. A National Endowment for the Arts writer’s grant will give him next off to finish his next book.

Painter Patricia Patterson was born in Jersey City in 1941. She met Farber and began collaborating with him in 1966. Their work has appeared in Artforum, Film Comment, and San Francisco’s City magazine in 1975, during Francis Ford Coppola’s reign as publisher.

Perhaps because Farber is the most problematic and demanding non-academic film commentator America has produced, he has received little scrutiny. I published a piece on him with a collage of his writings in december#10, 1968. Shortly after that, Donald Phelps devoted an entire issue of For Now, #9, to selections from Farber’s writing (with a nice Fielding Dawson sketch of Farber as the cover). My review of Negative Space in Cinema (Los Angeles) v. 6, n. 3, 1971, accompanies Bob Wilson’s bibliography of Farber’s work through The New Leader. Max Kozloff’s review of the same book in Artforum, September 1971, is an excellent account of Farber as critic. S. J. Perelman’s “Hell in the Gabardines” (1945) is humorously based on a Farber piece.

Points about Farber’s work:

1. Per Max Kozloff, Farber’s critical method is one of connoisseurship.

2. “The place where all criticism of American film should start: at the point where you feel ghastly after seeing one.”

3. A critic’s critic whose greatest influence has been on other writers.

4. Extreme importance of the position from which he works; like Daniel Boone, he instinctively moves to new territory when too many people begin working near him.

5. Deep dish American-ness. Aggressive use of contradictions: his own, the movie’s, the culture’s.

6. Depends on alert, active work by the reader. Always writes in non-specialized, non-academic, stubbornly vernacular language.

7. Criticism in which the movement from specification to continuation (see interview) parallels the movement from description to analysis.

8. Unlike more programmatic critics, Farber’s first step is to locate precisely the qualities of the work; his second is to organize a set of questions specific to those qualities.

9. Consequently, analogic rather than binary thought; a system which features complexity, simultaneity, and multiple positions.

These interviews took place from December 1976 to March 1977, Leslie Thompson participated in some of them.

Farber was born in 1917 and grew up in Douglas, Arizona, a small copper-smelting town eighty miles from New Mexico, 200 miles from El Paso, and a mile from Mexico, near such Budd Boetticher stops as Bisbee, Lordsburg, and Contention: “Bisbee us a beautiful city—it was in Fleischer’s Violent Saturday. It’s one of the most tiered hill cities you know of for that size. That’s where the copper mines were, and they located Douglas by figuring out how far a loaded copper car would roll downhill before it stopped; where it stopped, they put Douglas.” Douglas was the scene of the copper mining labor wars which launched John L. Lewis, and Aimee Semple McPherson surfaced there after disappearing in the California surf.

Farber’s parents ran a dry goods store; he describes them as poor lower-middle-class people. Both his brothers became psychiatrists; Leslie Farber has written several prominent books on psychiatry. “There was a ferocious effort on the part of my mother and father to intellectualize us—an incredible emphasis on becoming the best in any area; my brothers were the best in almost any area you could mention. They were the best violin player or the best piano player in Arizona, so I became a saxophone player.” Farber played alto and had his own jazz band in high school: “I would have played tenor, but that was before Lester Young.”

RT: What part did movies have in your childhood?

MANNY FARBER: I not only read about them, my family saw to it that we saw as many movies as we could. There was a theater right across the street next to the pool hall, five cents admission; they showed Buck Jones and Tom Mix. We would average three or four nights a week at the movies, Sunday in the afternoon, and often after school. I liked the Lon Chaney movies very much. I liked cowboys and slapstick comedies. I didn’t like MGM movies almost from the beginning; it seemed in that period it was Warners against MGM, and my family went for Warners—but we saw everything. I remember seeing Gary Cooper movies and liking them, Fairbanks movies and liking them, Pickford movies and hating them. Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer was a striking movie. I liked Sternberg’s Docks of New York a lot. My parents would take us to California each summer, so we’d spend three months in Venice seeing movies and watching them make movies.

Did the movies excite some curiosity in you—did you try to found out how they were made?

MF: No. We did a lot of criticism, just to go against my parents and the people my parents were involved with. I read a lot of criticism—I liked going to the library and reading movie critics as well as art and theatre critics. My uncle Jake taught us a lot about the movies by taking us. He’d graduated from Columbia University, published a poem every day in the local paper—The Brewery Gulch Gazette—and considered himself a movie intellectual.

Were you a serious kid?

MF: Serious? I was ambitious, and I was always critical.

Critical meaning analytic?

MF: Yeah. Skeptical and analytic.

Were you a loner even then?

MF: I don’t think that’s the right word. I was just the opposite. I was a little distanced from any of the areas I was involved in in relation to my friends, but I wasn’t a loner. I think that’s sort of romantic, because of the movies you’re interested in and I’m interested in, the writers we’re interested in.

[In 1931, the family moved to Vallejo, California, and Farber subsequently studied for a year at the University of California, a year at Stanford, and a year at California School of Fine Arts. While at Cal as something less than second-string quarterback, Farber claims that the coach’s gift of the nickname Snakehips ruined forever his football prospects.]

MF: I had my mind on journalism and painting; I’d made my mind up long before, and that’s what I studied. I’d been drawing since I was a kid.

After college?

MF: I went out determined to be a painter. To make a living I became a carpenter. Those were the days of the WPA [A Roosevelt government Depression era program to support unemployed artists] but—I don’t know, I didn’t like it; that makes me a loner. Since all the other incipient artists were going to the WPA, I thought it was a corny thing to do, so I went down to the union hall and looked at all the trades. Carpentry struck me as a noble one, more noble than plumbing. I had no talent for carpentering and never did, For thirty years. I flunked manual training in school.

What’s noble about carpentry?

MF: Just building a house with your own hands seemed a noble profession. That was the period of the Depression and afterwards, the period of Steinbeck, Hemingway, Faulkner, and the noble worker. The glamorous people were the peasants and laborers. The choice had a lot to do with that and not living off the government. It was a gruesome mistake.

Was the union good then? Could you work steady?

MF: Yeah. It always was a very easy way to make a living, so it was wisely chosen for a steady income.

You must have been pretty good—you still have all your fingers.

MF: They’re all broken, some of them several times. Carpentry and football.

Did you stay in the San Francisco area?

MF: Abut two years. Then I moved to Washington, D. C., to get away from my parents. My older brother was out of med school and interning at St. Elizabeth’s in Washington, so both of us went to Anacostia, a suburb of Washington, where one of our best friends was Nick Ray, pre-Hollywood. I worked on the Jefferson Memorial, Bethesda Naval Hospital, among other jobs. Then I moved to New York; that’s when I started writing to make a living. I was painting all the way through.

PAINTING

What kind of painter were you then?

MF: Pretty awful, I guess. I was involved with Cézanne in art school; he struck me as the most intriguing. So I painted what I thought was Cézanne, but actually it was very mediocre. Scenes around the house, around jobs, around unemployment offices, all done in a Cézannesque manner but what was actually weak realistic painting. I had a heavy indoctrination in art history: I loved it.

Later, I showed in the first Abstract Expressionist shows, exhibits arranged by Peggy Guggenheim, James Johnson Sweeney, Castelli, Clem Greenberg. Those were gestural and stain paintings, everything from pre-Noland targets to biomorphic shapes, with explosions of handwriting. I dropped out of exhibitions after a Tibor de Nagy show in 1957. I surfaced again at the Kornblee Gallery, in which a pre-environmental work which I transformed the whole gallery—ceilings, hallways—into a mobile, three-room painting. I painted the entire gallery. It horrified most, intrigued some, and Jill Kornblee has never spoken to me since.

I dropped out again until 1967, at the Whitney Annual: a twelve-foot-wide horizontal oval, rose-colored. I had a strong run on these paintings for five years: paper paintings, no supports, pinned directly to the wall—trapezoidal shapes, tondos, something that looks like two sawteeth, all primarily single-colored with a great amount of varicoloured underpainting which seeped through the top layer. A great deal of chance and process effects. The color and surfaces were melded together, and the goal was to make the luminous presence of each picture command a great deal of the room’s space, in front and to the sides of the picture. [For the new paintings, see Kenneth Baker’s article in Arts, December 1976.] I have been exhibiting regularly since 1967 in New York, Boston, San Francisco, and San Diego.

The things I do—the painting, criticism, and teaching—all crawl along the termite path I promulgated years ago; I am still painting directly against a white-elephant style.

One political fact to do with the paintings: no clichés. The paintings have nothing to do with Pop. Like Straub, I think it’s sinful to give the audience material it knows already, whether the material is about race relations or the car culture or the depiction and placement of a candy bar.

I’m taking what I think are new, advanced positions on color (not prismatic or tube color but organic, multi-mixed color), composition (not centered portraiture but a composition which uses the field of the painting as a performing stage for deployments, paths), space (dispersed, like a throw of the dice), line (like in early American painting rather than European), and texture (handmade, endlessly worked, slow, plodding).

I always consider myself a political person because I always present a program against and for something. The American Candy pictures, directly positioned against both abstraction and representational work today, should turn everything around, opening up endless options in space and degree of entry. The only duplications I’ve seen are the jammed table in Snow’s Rameau’s Nephew and the rehearsals in L’Amour Fou, and bits of Marguerite Duras’s movies.

WRITING

How did you get a writing job?

MF: From high school on, I read a lot of criticism. In San Francisco and Washington, I was very conscious of Otis Ferguson and Stark Young; their writing seemed to be the best at that time. I decided to set my sights on critical writing for The New Republic as a way of making a living. I wrote a very flashy letter to [editor Bruce] Bliven. It was purely tactical: (1) to attract his attention; and (2) to be so sarcastic and whimsical that he would want to see if I could really turn out something as exciting as I suggested I could. And it worked perfectly.

So I got a chance; there was no art critic, it seems. I suggested that I could write very good art criticism and they said, go out and try and I went out and tried, and they liked it. I made about $40 a week. That led to friendships with a lot of artists in all the professions. Betty Huling was there, and she was very involved with critics: Bunny Wilson (to use her name for him), and Otis, Malcolm Cowley, Nigel Dennis—this is the late Thirties. I got to know Isaac Rosenfeld, Saul Bellow, David Bazelon, Willie Poster and his brother, Herb, Mary McCarthy, Clem Greenberg, Philip Rahv. Terrific relationships with Robert Warshow and James Agee, and painters: Motherwell, Pollock, Virginia Admiral and Bob De Niro [Robert De Niro’s parents].

Ferguson went off patriotically to war in the Merchant Marine and died. The next day I was asking for his job as movie critic. I was never very sentimental in that period; I was ambitious.

But this leaves out all the landscape of my life—I mean what landscape means to me. I was always heavily involved in it. The landscape that I live in is very important, just as the language that I decided on as a critic was excruciatingly important.

What’s the relationship between that landscape and that language?

MF: Most of it is that I like to get it right: It’s a silly thing to say, but it’s very important to me that people know exactly the way our house looked, and where it was situated; that there was the Lyric Theater across the street from us, and at what angle, and how dark it was inside, and what kind of candy they sold, that it was next to a pool hall—that’s an icon of my memory, that street. And the way dispossessed farm people looked when they showed up during the late Twenties, and how Pyle’s Bunion Derby marathon looked when it came through.

And it still does. It irks me that people come through Del Mar and around the University, and I can’t get them interested in how important the trees are, or in how San Diego is a series of mesas and funny declivities—the land locates itself in relation to the mesas. It’s not a valley formation: it comes down in a triangle.

It seems so central to me not only to see it right, not only to get interested in it, but if you’re going to write about it, you have to get it extremely clear and accurate.

How did you organize your prose style—it’s distinctive, not something you just tossed off.

MF: I developed a very facetious style of letter writing; I never wrote a straight letter in my life, they were elaborate verbal games. And I came up through the sportswriters of the Twenties and Thirties—I wrote sports for my high-school paper—the laconic, tough, straight ones, straight in the sense that they could get one word to say what they wanted, that it would stay in place. I didn’t go for Grantland Rice or Ring Lardner; the style came a lot from Twenties sportswriters, but I can’t recall their names. I never got rid of a fault in my writing that comes from sportswriting: you always build up a star. And in sportswriting, you never leave the reader feeling it was an unimportant event, that it was worthless to attend the game or that the player was an uninteresting athlete.

That’s why sports are built around winning and losing.

MF: I’m not sure they’re built around that so much as they’re built around the excitement of the character and the mood. You get the way Mel Ott stood in the batter’s box. Anyway, right or wrong, I was raised in that kind of sportswriting. It’s Three-Finger Brown, that kind of title, which is so close to the way Howard Hawks names his people—it’s a direct crossover. So my writing has always been off because it glorifies too much, like The Ox-Bow Incident, a terrible review, or the Southerner review, which I backed strongly because they were on the right side politically.

That writing gives great care and emphasis to verbs.

MF: Very terse. The word had to fit the image it was about, and it had to hold its place; I couldn’t stand any generalizing in language, in journalism. I was heavily grounded in orthodox art, all the way from MGM to the type of paintings my parents would put on the walls to the type of novels my mother read to the type of writing we were encouraged toward in school. But that gets away from the question and back toward the idea of being a loner.

I wasn’t a natural writer at all, I had a good sense of the way writing should go, to excite people and entertain them, or to place them in positions of judgment. I knew I was hip at any point in my life. That link between language and landscape is supremely important, and I’m still involved in it.

Does the specificity in your criticism come from that same sportswriter school?

MF: Undoubtedly. Also that Who, What, Why, Where, When thing was stamped into me. Who is this guy, where does he come from, what’s his background, why are you writing about him, and always you have to explain everything. It’s a good rule; it can lead to a kind of jejune presentation, though.

Perhaps that’s a way to distinguish your writing from similar work: yours is more concerned with where the object came from, while other writers are more concerned with where it’s going—like Durgnat, also a very broad and allusive writer who cross-references a lot, but seems to do it more about the film’s functioning in society, where it’s going out to. Much of your specificity is about what went into the film to get it where it is.

MF: Maybe that’s why I’m so dogged on what’s hot now, or on movements in careers, what to pay attention to. The reason that Durgnat has so much mobility in his writing style and so does Godard as a critic—is that he can move laterally, peripherally, much quicker. It’s very hard for me to put down any noun without having to explain why I’m using it and where it comes from. In other words, I have to do a lot of journalistic positioning, which is a waste of time.

From the beginning all through your writing, there’s a sense of writing as a carefully crafted object. For some people, writing’s like whipped cream, something they spray on so they can shave; it becomes transparent, it’s supposed to vanish, it’s at the service of ideas, it has no character. It’s the difference between the idea that the frame is a window into story, something you see through, versus the idea that the frame is two-dimensional, has certain proportions, and is composed upon. Your writing seems consciously organized as a style: verb-centric, stingy with adjectives—or more accurately, making each adjective an event.

MF: It’s topographical. It’s all that I think criticism is about.

When you began writing with Patricia in the late Sixties, what did she bring into the process?

MF: Patricia’s got a photographic ear; she remembers conversation from a movie. She is a fierce anti-solutions person, against identifying a movie as one single thing, period. She is also an antagonist of value judgments. What does she replace it with? Relating a movie to other sources, getting the plot, the idea behind the movie—getting the abstract idea out of it. She brings that into the writing and takes the assertiveness out. In her criticism, she’s sort of undergroomed and unsophisticated in one sense, yet the way she sees any work is full-dimension—what its quality is rather than what it attains or what its excellence is; she doesn’t see things in terms of excellence. She has perfect parlance; I’ve never heard her say a clumsy or discordant thing. She talks an incredible line. She also writes it. She does a lot of writing in her art work; she gets the sound related to the actuality in the right posture. It’s very Irish. You don’t feel there’s any padding or aestheticism going on, just the word for the thing or the sentence for the action. I’m almost the opposite of all those qualities: I’m very judgmental, I use a lot of words, I’m very aesthetic-minded, analytic.

PATRICIA PATTERSON: If it were up to me I’d never dream of publishing anything—it always seems like work in progress, rough draft. But he’ll say, “Just leave it at that.” I’m more practical than he is. Manny is willing to stay up all night long, take an hour’s nap, and then do another rewrite, retype, collage. He’s the workhorse of the pair of us; he does the typing. He will initiate many, many rewrites, come up with new tacks to explore when we’re way beyond deadline and patience.

MF: I’m unable to write at all without extraordinary amounts of rewriting. The “Underground Movies” piece took several years to write. An article on bit players was stolen from the car—a funny thing to steal on Second Avenue and Second Street, but it was stored in the lid of an Underwood [typewriter] at about the fifth year of its evolution. I’m not a work-ethic nut, but the surface-tone-composition in everything I do—painting, carpentering, writing, teaching—comes from working and reworking the material.

PP: Maybe we could paint a little picture of the writing process. Also, I’m a little more scrupulous. I’m less willing to let the statement be made: I’m always saying, that’s not exactly true, or that’s not fair or look at this other side.

MF: They go together—to get the sounds right and to get the idea attached to it. She cannot be unscrupulous. We have ferocious arguments over every single sentence that’s written.

What are the arguments about?

PP: For example, India Song has never been resolved and boils both of us. I still balk at the languor, the fashion-model look, and I have no patience for the slow tango pace Duras sets up with camera and actors. It’s beautiful but it offends me.

MF: Straub was wrong when he said India Song’s soundtrack interested him but not the image. The image, a tracking shot through the grounds and across the building of the consul’s residence, is determined by the music. The music was played constantly on the set to regulate the way the camera and actors move. Even though it’s slow action, the people are never still: action has been slowed down and stasis speeded up. There is barely a difference in the two; as in late Snow, Altman, Rivette, everything has been pushed to the periphery, characters constantly entering and exiting a movie that is mostly at the edge of the frame. What about the deep plum glowing color—what would you call it, Victorian? Like Caravaggio, but softer than that.

PP: I have the same difficulty reading Duras. I don’t quite buy the leftist politics. Marxism with a silver spoon in your mouth, Marxism expounded while lolling in an exclusive Alpine health spa. Although I liked Nathalie Granger very much. What troubles me is the pampered droning voice. There’s so much narcissism in these rebellions against capitalism.

MF: No one sticks to Duras’s difficulty enough. It has to do with the emptying out, the willingness to have bare stretches: the time it takes a washing-machine salesman to move from a car; up the path, and into the suave company of two elegant women. That’s the kind of thing I like in Duras. It’s the join between persistent, drawn-out time passing and the fact that life is at a standstill. It’s cut itself off from active life as it was lived in the colonial past and is waiting for some utopian state of affairs. But the movie is going to remain stubbornly implacable until that time. Duras should direct a Continental Op story: two grudging, monosyllabic writers [Dashiell Hammett wrote a series of Continental Op stories before going on to Sam Spade and then The Thin Man].

PP: It occurs to me that a difference between us is Manny’s pull towards Minimalism, whereas I’ve never been able to do abstract work. It usually comes down to a difference on Herzog’s cruelty, say, or the safe-playing in History Lessons.

So it doesn’t come down to this verb or that noun?

MF: No. I like to get an opinion, and Patricia’s obsessionally against opinions. There’s always another side to every flicking movie or painting there’s always an assuaging side.

Often you two resolve that through multipurpose sentences. You run the idea through the first half of the sentence and then reverse it through the second half, but you don’t end up cancelling out the meaning: you end up getting both meanings.

PP: If you ever saw us at the end of writing an article, it’s…

MF: It’s death. It’s like a cemetery.

PP: It’s unbelievable, having sat through this sedentary thing of fighting, eating junk food, not washing your clothes—oh, it’s awful.

MF: Except she sleeps.

PP: I sleep. I haven’t Manny’s stamina, and I don’t have his dedication, at all.

MF: For one thing, Patricia doesn’t have a history as a critic, or a love of criticism.

PP: That’s not true. What do you mean?

MF: What I meant was that she disbelieves, I think, in judging the work.

PP: I like seeing creeps get their just due.

But you two seem the opposite of that with your advocacy pieces. The Taxi Driver piece [Film Comment May-June 1976] is carefully balanced—but some of the pieces for City! The corner turns so suddenly. In the first article about Hollywood’s hotshot young directors, the first two paragraphs read like a recruiting poster for the new Hollywood, then in the next few paragraphs it goes through a corrosive tone change. So many of the references, like referring to Ferguson’s citation of the iron fence in Citizen Kane, I take to be references to Coppola’s own Charles Foster Kane life-style.

MF: I’m very proud of that first article for City on the New Hollywood

PP: I kept saying, “Unnhhh”—not because I was afraid of Coppola, but because I thought we weren’t covering each film enough, and that to write this provocative a piece, you really have to back it up.

Are there things in common in painting and criticism as you practice them?

MF: The brutal fact is that they’re exactly the same thing. American criticism doesn’t take cognizance of the crossover of arts, and American painting doesn’t take cognizance of it either. It’s always very provincial. I don’t get why other critics don’t pay more attention to what’s going on in the other arts, because I think the moviemakers do; the styles are so pertinent. The kind of photography you see at any point is that way because of what’s being written in novels and painted in pictures. Like the crossover from Hopper into writers like McCoy and Cain, the film noir movies—scripters like Furthman and Mainwaring—all over the place at the same moment. You couldn’t have had that kind of imagery that directors and screenwriters were trying for, unless it were the most important thing for painters to be doing. It’s as if there were a law in film criticism that you’re not supposed to get involved in the other art forms.

PP: My first experience with Fassbinder’s Merchant of Four Seasons was a painter’s reaction, shock and envy that someone had gotten there first. Specifically the scene in which Irm Hermann, the wife, bustles around the kitchen with the daughter doing her homework, dejected Hans staring out the window. Visually, the scene has to do with the wallpaper, patterned oilcloth on the table combined with the enamel-like color, shadowless Fra Angelico lighting, with everything both ecstatic and ordinary at the same time. Straub and Fassbinder in 1972 were far in advance of what representational painters were doing then. Pearlstein was doing the studio thing, the photo-realist Estes-Goings were doing a single-item Americana, a pickup truck or a closeup of an escalator.

The first impact Straub had was visual. I even made a small painting of a still from the tense dining-room encounter between two old political enemies—“Would you trust a Nettlinger”—Schrella and Nettlinger. Not Reconciled is terrifically interesting, visually. The curious motif: a bird’s-eye view of a two-shot, the soberness of the people combined with the black/white richness, the kind of rigor and integrity with which the documentary shot is heightened. The fact is that visually the Straubs are so beautiful. History Lessons: the scenes in the garden with the big flowers. I always liked the oversized stage with tiny actors in The Bridegroom, the Comedienne, and the Pimp; it’s such a misreading to say that he’s only about dry intellectualism.

MF: To go back: I think what I set out to do with criticism in the Forties—it was always the same goal, I had about 800 words, a column-and-a-half in The New Republic—was to set out the movie before the reader’s eye in as much completeness as I could, in that topography. I had to develop a picture which could pull the audience in and give them these sights without their realizing it, and which would divulge the landscape of the film as accurately as I could get it. That involved a lot of color work in the language and in the insights—color work in the sense of decorative quality. Topography changes every decade. Now we’re into a new topography.

The characteristics you begin to get at in the Taxi Driver piece.

MF: Absolutely. It’s totally involved with my experience as a painter-writer-teacher. The topography has to change, but I hate to keep using that word. What the reader has to find out changes. A great deal of it comes from the fact that painters, musicians, composers are involved in collage at a certain point. They didn’t really know the meaning of the word in the Thirties and Forties; collage didn’t come into movies until Godard.

One reason it seems important to work collaboratively at this moment is to take advantage of what you can get with collage, putting two disparates together—not only working with Patricia, but in class, in discussion with other film people, things that are said on the screen—just the effect of putting screen conversation into an article. I’d never do that in the earlier writing, not that I didn’t want to but it never occurred to me that it was important. Now it seems so important to get these other viewpoints, other ways of saying things, hitting against other types of discourse to get the feeling of multiples.

The language has changed, the observation has changed in movies. The way a person looks at either a movie or a painting is so different from the way it was four years ago, ten years ago. So is the way a person makes a movie, a painting, or a short story—the goals. Your audience has changed. It knows certain things, so it’s silly to even do them.

Godard is an example of that: moving your style along because the audience is in motion.

MF: Godard is supremely a man of the Sixties. He was enormously gifted for the kind of art that was important in the Sixties—in painting and Photography, in writing—and he used it. He’s very shrewd; he’s moved into video and documentary; also biography and continuation. He knows he’s done as much as anyone could do in that area he was in, but he also knows that there’s a great, great abhorrence in the arts right now about style—fine style, fine sensibilities, taste, getting things said entertainingly. He knows that it’s all sort of phony, so he’s trying to get back to a more truthful presentation.

CRITIClSM

What’s “continuation”?

MF: It’s an idea that’s been missing from criticism. Continuation involves constant attempts to stretch out the moment—as in L’Amour Fou—expanding its parameters step by step. In the Rivette, it involves moving back from a romantic discussion between two neurotics to see the space they occupy, then to perceive the space as a stage, then their discussion as a rehearsal, and so on; Altman does it with more and more layers of voices on the—soundtrack

Continuation is about entry. It’s anti-conclusive, it stresses involvement and it grows out of the termite notion. You keep moving forward and extending the time element as you go.

So when you say continuation do you mean that it opens up large areas in which the critic operates? Or are you talking about taking the criticism further toward something in particular?

MF: Obviously, it’s related to criticism in the past, and in the past criticism has always been too brief. There’s a desire to know more and more. Why? One of the most important facts about criticism is obvious: it’s based on language and words. The desire is always to pursue: what does the word mean, or the sentence, or the paragraph, and where does it lead? As you follow language out, it becomes more and more webbed, complex. The desire is always to find the end. In any thought you put down, what you’re seeking is truth: what is the most believable fact and where is the end? You always have to seek the end.

Do you ever get to an end?

MF: You get to an end, but by then the thing is filigreed; it becomes like Henry James or Middlemarch or Parade’s End or Melville, to name work I love. You hope to get to the bottom of many threads. But in any case, you’re always pursuing information if you’re involved with words, with writing; I know what seems necessary for me: you have to get as much information as you can, get a grip on as many parts of the movie and what they mean as you can, and you have to find out how applicable it is to knowledge, as it is at this moment, and how impelling it is to perpetrate that kind of information. You have to meet all those problems if you’re a serious critic Why? Because I think almost every other critical approach I know is derelict.

Without direction?

MF: No, it’s backwards. It’s all been done. It’s without direction, that’s true, but also it’s too short; it doesn’t argue what it’s stating.

It assumes it?

MF: It makes forays into one kind of idea or another. In other words, in The Wind and the Lion, there’s a key scene of Teddy Roosevelt [Brian Keith] sitting on the grass at a gunnery rang, talking to his grandchildren. Obviously, Milius has a close feeling about Roosevelt; but why does he idolize him? Does that scene bring forth the idolatry? How much irony is involved? What does it have to do with the militarism issue, since it’s a gun? Why is the golden autumn lighting so singularized, intense? Why is Keith faced away from the main flow of both story and character, in a didactic position relative to the camera? Why does the movie segue out at that moment? Is it making a statement about U.S. militarism or colonial ambitions—and does Milius believe this implicitly? And if he believes Roosevelt stands for some order of the gun, or that the U.S knew the right way and was trying to spread the gospel of democracy at its best around the world—is that really what he believes? Or does he believe that it’s a fault that inevitably leads to Vietnam? Or does he believe in the Zeitgeist of guns and gunmanship?

He might agree with all the position you’ve lined out.

MF: I don’t think it’s important to ask Milius those questions; I think it’s important for the spectator to want to know what he’s seeing. If you’re dealing with words, they have to start at some point. If you’re dealing with events, then a person wants to know more and more. There’s a passion right now for biography and biographical art. In that scene, you know that a lot of the material is more than flat dramatic data on Roosevelt; you know that it relates to Milius. He’s interested in confessional work, in betraying himself. A lot of art in the Seventies is not only interested in confession or biography, but is often interested in mocking it—remembrance art. The only truth now, for artists, is to position themselves so that they’re speaking directly at the audience, and speaking about something that they like to know about: divulging themselves.

It’s the crossover idea again: why people are doing performance pieces having to do with biography or pseudobiography, paralleling Godard, Rohmer, Fassbinder, Herzog. You get the same type of interest in commentary as well as in style. But this kind of work is being criticized with the language and mentality of the Fifties, the Forties, the Sixties; so much of how it’s valued is involved with auteurist work.

What is the role of evaluation in your critical work?

MF: It’s practically worthless for a critic. The last thing I want to know is whether you like it or not: the problems of writing are after that. I don’t think it has any importance; it’s one of those derelict appendages of criticism. Criticism has nothing to do with hierarchies.

Your writing features an avalanche of allusions, to other movies, events in history and culture, other arts, ideas, popular phenomena. That’s a kind of criticism not much practiced; currently we see more narrow, New Criticism-inspired analysis.

MF: I used to work that way; you’re suggesting I never did. When I first started, I thought you could take a painting or movie and get all the information necessary by focusing on it and using your head. Most of that criticism was heavily formalistic; at least it was trying to get at the technical structure. The newer work is a complete reversal of that type of criticism.

The best part of writing is where you have a good deal of copy and can think about it, figure it out. The best part is the tactics: you can bring all these tactics to bear on what you’re doing, and get the kind of aura where you surround the subject. But you have to make the reader pursue it without realizing it, so that he’s getting further into the corners of the movie. I do a lot of that; I always have. I do a ton of examining what’s been written, then inserting things to build up the room of a sentence or of a paragraph so that it’s not localized on one spot. We use a lot of dialogue to bring the aura of a movie back into the reader’s feeling. One of the moves I used to do that now seems horrible is referring the reader to the director’s other movies, so that he’s shifted out of contact with what you’re talking about.

What made you change?

MF: Principally, dissatisfaction with criticism and what it’s doing, accomplishing. My own wasn’t getting enough of the heart out of the work, and if it doesn’t get enough information to the audience, it isn’t giving them enough—enough exact definitions and precision writing. It left so many vast swamps of unexplored argument that you could drop the whole industry through the empty spots in that criticism.

Are you now trying to exhaust each point you raise?

MF: I’d like to. It’s not that we don’t want to. We want to take the reader as far into the work as, say, Ford Madox Ford takes Tietjens in Parade’s End. Instead, criticism is too often decisions and didactic, positive leading of the reader: this is what the movie is, period.

Underlying your writing is the assumption that the reader has seen the film, even though the surface presentation often seems journalistic—‘you haven’t seen this yet’. Most of what you say only pays off to those who have seen the film.

MF: Criticism should make that assumption and encourage it. The audience should be fantastically dialectical, involved in a continuing discussion of every movie. Rather than stressing superlative movies or guides to culture or antiwar tracts, feminism, whatever, this dialogue should attempt perusal and continual reassessment. The pursuit in movie criticism as well as in movies should be after ideas, and the ideas should engulf both the subject and the people using the ideas. The place of both criticism and movies should be finding out, getting intelligence, not making hits or keeping people from being bored. The whole thing has to be rearranged.

Your writing moves from the specific—description, allusion, citation—to analysis and ideas almost instantaneously, as if they were the poles of a short continuum. You sacrifice the in-between, academic show-your-work steps for compaction.

MF: Neither of us believes in the other way. You must stay on specifics, stay on top of the movie. Everything it says—that’s what the subject is. The person making the movie should be held responsible for everything that’s said and shown, and so should the people seeing it. It should be a massive kind of intelligence. Criticism today is almost an end-to-end waste because it’s pursuing the wrong thing; it’s an auteurist criticism and the audience is asleep.

You’ve talked about trying to communicate the excitement of the film experience. Can you go too far in the direction of say, promoting the film by duplicating its excitement?

MF: I could only be interested in criticism that tries to get the whole thing, the reaction to the film. If the pieces like the Fassbinder or Herzog pieces in City come off as promotions, it’s because they weren’t long enough, daring enough—not because they praised more than they should. They didn’t go deeply enough; didn’t get the reverse side.

How far do you have to go, then, to be mimetic in this kind of criticism?

MF: I don’t think you can be mimetic enough.

PP: Mimesis isn’t all flattering; a lot of it as easily goes the other way. In fact, it’s one of the most effective ways to ridicule a movie.

MF: Do you get much of it in criticism today? Agee did a lot of it, but he was gifted; he could do it, but it works wrong for him.

Maybe there’s a difference here between description and evocation.

MF: Evocation’s what we mean. The whole opening of the Godard piece for Artforum was a collage. When the article was originally written, it seemed very unsatisfactory.

PP: For the first time, Phil Leider, the Artforum editor, refused an article.

MF: We needed to enliven it. We thought about it, and one of Godard’s favorite moves is lists. So: why don’t we do his movies as a list—and what shall we use as the categories? We said animals, because Patricia’s sharp on that. It gave the whole article a change of pace.

PP: It’s the idea of writing about the film in a way commensurate with the way the filmmaker’s mind is. From then on, our idea was that there shouldn’t be a stock way to write about things; the work’s qualities should influence the structure of the piece. The work doesn’t live up to it, but that’s the idea.

MF: I’m puzzled about why the mythic tendencies in genre movies are so important today. It misleads the audience and the character to turn it mythically instead of to turn to more and more detail, precision about the characters. To turn the Bremer character in Taxi Driver into a lone-wolf Gary Cooper, to turn him so that he becomes mythic, is just awful.

PP: It makes it familiar instead of threatening, because we all know about The Outsider.

MF: Also, it makes it familiar as pleasure, and that’s where everything seeps out of the work for the wrong purposes.

PP: The same with Badlands: they become Bonnie and Clyde again, and we know how to take pleasure in that. We can identify with them building the house up in the tree, the feeling of pioneers in the Old West; there’s a space between that and the fact of eleven murders. It’s easy to become sensually involved with it.

MF: I don’t think Bremer’s book had any of the mythic element. It was an enriching experience to follow this fellow on his travels to Canada and back trying to get Nixon. The hotels he stayed at, what happened on the trains, his troubles with women.

Is this use of myth to secure easy, unreflective sympathy different from Herzog, Rocha, Fassbinder etc.? Do they use identification in other ways, or totally avoid it?

PP: Straub certainly doesn’t, and Oshima fractures the attention among so many characters that there isn’t one who becomes the glamour character that Hollywood films focus on. I mean, De Niro is a very attractive person, with him in the center of so many shots, it’s impossible not to have some kind of identification. With Kaspar Hauser, I think Herzog does make him something similar to De Niro.

MF: It’s a mistake, too. A very important move in art—you get it in the novel, in Duras, Rivette, the best of Altman, late Snow—is an idea of process art which has to do with a diversionary scheme where you don’t get centralized on one character or on a cast of characters doing something. Now the interest, over several areas of art, is on what’s possible if you get away from the idea of the work as the course of life a person takes or the role that one person has in an environment.

I’m more interested in getting at the truth of the way we live by trying to slice through the event from a different angle rather than through the one person or the three persons involved in the event. If you take the event as a congeries of elements, and the event isn’t centered or focused from a single viewpoint, then the viewpoint is about that dispersal.

You laid out a choice between taking the character into myth or into detail. Why are those opposed?

MF: Because myth makes the character larger than what’s around him. It isolates the character from his job, from the place he lives in, from the relationships he has with other people. It makes that person larger and other people smaller, so that it’s not a balanced dialectical situation; it’s like a triangle where you know who’s on top.

Within the older kind of cinema, it’s only—and rarely—in comedies that you find a film in which there are two focal crazy people.

PP: Like Laurel and Hardy, where you get the two nuts going back and forth; you don’t get it with Charlie Chaplin, the big hero.

It’s still hard to find a film where you have two equivalent but separate crazy entities. In team comedies, you usually have two halves of the same personality in separate bodies. That’s not the same.

MF: The position of Laurel and Hardy in their scene was revolutionary: it was dispersed. They’re always viewed in relation to American suburbanism, possessionism, commodityism, or copism. That’s very different from Chaplin or Keaton in that they’re rather small items in a space, and the space is political, social—prestige to get the money and be accepted in society—and the viewpoint never loses that distance on them. Instead of being virtuosos commanding space, the way Chaplin is, dissolving space around them.

In a way, Chaplin controls space outside the frame, not just inside the frame: he can make the camera come or go. I prefer Keaton’s frame control asceticism: he’ll operate inside the frame, but he won’t obsessively adapt the frame to himself.

MF: That’s true, but the thing that intrigues me about Laurel and Hardy is that they’re sort of lost in the frame, they don’t work it to their advantage, either aesthetically or egoistically. That’s what’s so exciting about a Duras or Rivette movie. There’s a great deal of reality and truth, and it’s magic; you forget the idea of a linear construction into a story or into an event. The edge of the frame is where art is today. That’s a big statement, but that’s where the fun is. Not only the edge of the frame, the edge of the soundtrack. Not like Bernard Herrmann’s Taxi Driver idea, in which you’re inside the movie, there’s nowhere to go, it’s like a bowling alley.

I think one of the problems with my early criticism is that it assumes you’re supposed to be able to follow everything and then get this meaning of a scene. I don’t see how or why anyone should be expected to get the meaning of an event in a movie or a painting. That’s a place where criticism goes wrong: it keeps trying for the complete solution. I think the point of criticism is to build up the mystery. And the point is to find movies which have a lot of puzzle in them, a lot of questions.

How does criticism go about building up mystery?

PP: I don’t think he means build up the mystery I think he means enter into it. You don’t concoct a mystery, you acknowledge it.

MF: Acknowledge it and make the pursuit, get the reader pursuing the mystery. It’s very difficult to get at the reason for a given move in a scene, and it’s very important to create the aura of a question inside the situation.

What is meaning for you? Is it something directly balanced off against mystery, or are they separate in a work? Or are you even concerned with meaning?

MF: I am concerned with meaning, but I’d have to talk about an individual movie.

PP: Meaning could never be a singular thing: I can’t imagine that there would be a meaning.

MF: In The Bridegroom, the Comedienne and the Pimp—a collage movie, about twenty-five minutes, in which are put together disparate types of drama—for one section, Straub just put the camera in a car and the car has gone around the red-light section of Munich or wherever. It’s a night scene: you get a curved scene of an impoverished or desolate street; occasionally you get the figure of a prostitute supposedly standing there. It’s a very lonely, unpopulated street—you know that meaning. But there is the mystery of why he hit on the curvilinear move; it’s a very odd curved path that the camera takes.

PP: It could just be that that’s the curve of the road.

Or maybe he’d just seen Alphaville, which came out the year before.

MF: It’s full of references to Alphaville, as a matter of fact. But does that seem contradictory? There’s a kind of mystery in art work that’s always there. There are meanings to be divulged, but you have to create the pursual element.

Perhaps due to the publications your work appeared in, your early work seemed to be dealing with the nature of a popular art, one which everyone saw. Then there’s a shift in the Sixties and you focus on an art for the few. The switchpoint seems to be between Cavalier in the mid-Sixties and Artforum from the late Sixties on.

MF: I’d forgotten I was so polemical and rambunctious from the outset. I always had a sense of where to position myself; that seems important. That stuff I was divulging about a new criticism is totally involved in my reaction to what others are writing. I’m a reactive critic: I like to listen to someone else and then cut in.

It was also about the time that the scheme for writing criticism changed. I was very tired of the way the articles in Cavalier and The New Leader sounded: I hated them. “This Is Right and That’s Wrong and There’s Your Movie.” I was suffocating under a need to find out why a movie either was failing or succeeding. With the Artforum work, the terrain and possibilities of criticism suddenly opened up. That’s when I started using a lot more conversation from the films. That’s where the collaboration with Patricia started. Her sensibility got involved and seemed legitimate to me; my sensibility for the movies widened. And we became interested in a new critical process: how to reach an audience which was almost all high aestheticism. We played around with describing events and hooking an audience from just the right viewpoints instead of parlaying value judgments.

PP: The Artforum pieces I feel very attached to are the Godard, the Hawks, the Fuller, and the Siegel. All auteurist pieces, but they took a lot of work, much more than the Wavelength piece. When I read what we did on Snow, I blush.

Do you experience a split between your personal responses to a film and a more balanced, objective, analytic response? How do you handle it?

MF: I don’t think I’ve ever written about a movie as I’ve seen it inside the theater. Writing throws that response out of whack. The problem of criticism starts at the obvious point: when you start typing and thinking out the work. The role of the movie-goer is different from the role of the critic; the two shouldn’t get mixed together. With the new structuralist criticism of Young Mr Lincoln or Pursued, you’re getting the realization that all that criticism of Agee’s and mine was more like a moviegoer—didn’t even get into the role of a critic. Even in an article like Agee’s on comedy, he keeps writing it as if he’s inside the theater with his father. I think the truth and believability in writing is different from the truth and believability inside the theater. That’s why it’s important that all criticism be reassessed constantly—too many moviegoers doing a pseudo-role as critics.

So that despite your prose style—as unmistakable as a Parker solo—you’re trying to work away from the personal voice?

MF: More important than a personal voice is proving what is said. You set up a position, you have to prove it. I don’t think a moviemaker’s role is to show you things he likes or dislikes; and I don’t think a critic’s role is in that area either. I like Back and Forth, the Snow film, very much. I’m sure he doesn’t want me to. He’s not trying to show me how much he likes about either the classroom he’s shooting, or the crowd of people in it or the movements the camera can make. He’s interested in organizing the space and movement so that it’s an image, a vision.

Does that mean your role as a critic is to help your readers see this use of space to create a vision—if they can’t get it by themselves?

MF: I don’t agree that Patricia and I have better eyes or more experience to deal with a movie than the spectator; that’s suppositional. You’re supposed to get at the truth of a situation; that situation is the movie; you as a critic have to burrow into the situation to find the truth. You don’t know more than the people around you, but you have more time. You can go to the movie more times, spend longer discussing it with each other. Then you proceed as I’ve described.

I can’t see any difference between writing about a porno movie and an Academy Award movie—both are difficult objects. The writing should draw you in and provide you with a lot of intelligence about the moviemaker and the issues—whether it’s fucking or something else. Why that should add up to four stars or a hit movie—I think that is obscene and degrading for criticism.

What about pleasure? Does watching films give you pleasure? How do you deal with that in your criticism?

PP: We try to get it across in our descriptions of scenes; we usually pick out a scene that was either very funny or very delightful and try to talk about that. Sometimes we didn’t know that it was until we started writing about it, and then we got excited. Two films that we absolutely loved recently were La Bête Humaine and Nosferatu.

MF: Pleasure is always involved, the fact of whether we liked it or not, or a good scene, a good actor.

ONE FILM

PP: Manny taught The Far Country recently, with Ulzana’s Raid. He kept talking about it having a richer sense of space than Ulzana’s Raid. I kept seeing these odd scenes with Jimmy Stewart throwing guns to two guys, then the steamboat being right behind him, space being extremely artificial. So there’s no real, natural sense of space, just odd juxtapositions.

Remarkable how often in that film Anthony Mann goes for a formal two-dimensionality, whereas in most of his films he’s interested in opening the frame successively into the center of the screen. Also the way he uses so many enclosures.

PP: There’s funny dialogue in The Far Country, pointed writing from which you pick out lines. Stewart is always saying, “Why should I? Why should I go back and help them?” And the little French girl will say, “If you don’t know, I can’t tell you.” And the lines her father is always saying out of nowhere: “Did you know a cow had four stomachs?” We were trying to think of five lines from the films during the course that would be knockout lines for the final exam. The one we thought of from this film is the little French girl’s: “Don’t call me freckle-face, I’m a woman!” A lot of the lines are like that. Walter Brennan talking about getting a little house in the country and settling down with Stewart. And the “Bear Stew” sign. Gannon’s lines: “I’m gonna like you. I’m gonna hang you, but I’m gonna like you.”

MF: The movie seems so cunning and likable; it’s interesting, because it looks so phony. And it reminds me of Yojimbo and One-Eyed Jacks—the destroyed hero having to hole up and regain his physical skills over the months. And the fighting underneath the floor; do you think Kurosawa got it off The Far Country?

Why did you choose to teach The Far Country?

MF: I always saw it in pieces on TV. I wanted to see it in continuum. Once I got it, it interested me how Mann was making his points or effects. I never could figure it out. There are so many matte shots and so much off-location stuff and yet it’s a very lyrical film.

He even gets poetic effects from bad back-projection and bad day- for-night by darkening and thickening them.

MF: What motivated him to do it that way? It seems almost psychotic to do that. Except it also seems enchanting to do an Alaska movie inside a studio, and then to have critics write about it as if it’s a masterpiece of location work.

Chaplin did his Alaska movie that way too. There’s no depth to it; could have been done anywhere.

MF: Not only no depth, it shrieks of its synthetic quality just as The Far Country does. It takes your hair off. Then you wonder what the relationship of Borden [Borden Chase, who wrote the film] to Mann was; it seems so much Chase’s conception.

It’s a near remake of an earlier Mann-Stewart Western, Bend of the River, which Chase also wrote, borrowing heavily from his Red River script.

MF: I kept thinking The Far Country was a continuation of Red River at the end—they just kept moving the cattle north. Stewart’s is a very good performance.

PP: He sets up the mental attitude of someone who really doesn’t want to be bothered; he makes it very convincing. The townspeople try to make him conform and all that sentimental stuff so that at the end, when he does his flip-flop and becomes the good guy/good citizen, you feel sorry.

What is it that’s important to teach about Hollywood films like this? Why is it that you keep trying?

PP: I don’t know how you could not teach them. They’re just among the most important films ever, so you couldn’t just cut them out.

MF: That’s true. I’m slowly coming back to them; I imagine I’ll be teaching them a lot more.

Aren’t they a lot harder for students to accept?

PP: They didn’t use to be, then there was a big turnaround. Maybe the problem is putting a couple of genre films in with all these contemporary European art films—Kings of the Road and Mother Kusters—as we did. We also showed La Bête Humaine, and we got some resistance on that too; not as much.

MF: The big resistance was on The Far Country. That shows how badly it was taught. I did the obvious commercial thing of running Ulzana’s Raid first, so I was left with only two or two- and-a-half hours to do The Far Country. I used to be able to teach six movies in a three hour class, and 1 seem incapable of teaching more than one in a six-hour class.

Are you getting around to showing the entire movie now?

MF: I show one movie. I not only show one movie, by the time they’ve finished with it in one week they’ve seen it three or four times. But they still haven’t seen it enough, and we haven’t talked enough. That’s one of the reversals that’s taken place in my teaching: I do still show fragments every which way—backwards, without sound—but only after they’ve seen the movie all the way through. It’s disconcerting when we spend forty-five minutes talking about a five-minute fragment. That cuts into a six-hour class.

Why must you teach Hollywood genre films? The thing that intrigued me about The Far Country was: What was motivating these spatial moves? And why he was getting at what seemed to me a rather beautiful lyricism of Stewart, both his scale and the way he moves in a three-dimensional scene. And what Patricia was talking about: his character, which is very exciting even if it’s somewhat clichéd.

Stewart’s such a cracker-barrel philosopher, it’s hard to figure out giving him that role—a role where he’s totally alienated from everyone else in the movie, from everything in the landscape. The character is deadly private and sort of bitter. Maybe not bitter, but it’s a kind of malevolent privacy where he doesn’t want to explain anything he does, and yet he understands everything that’s going on around him without actually taking part in it.

PP: He won’t give an inch; he has a very strong sense of who he is and what he stands for; he’s always making judgments on what he will partake of and what he won’t; and he can’t be maneuvered by anybody.

MF: He knows the advantages of not being social. I think the profoundness of the role as against maybe Bogart, maybe Brando, maybe someone else—the difference here is that the anti-social role seems so justifiable.

As opposed to what?

MF: Everything else in the movie. Also progressivism itself, liberalism, the whole idea that you advantage from democracy, from helping your neighbor, from building cities or dams or baby hospitals. What attracts you in that character is that the director, the writer, and especially Stewart realize that not being part of society is wonderful.

It gets you out of all the disasters of helping your neighbor or providing steaks for the population of Skagway or keeping that awful actor from being shot every other second—Jay C. Flippen. Probably the worst actor that ever moved into a movie. Nick Ray, in his first movie, tried to transform him.

Aside from Stewart’s own Fifties parts, another one is John Wayne’s character in The Searchers: the whole film again is about being outside of things.

PP: But Stewart is much more convincing, more detailed and much finer.

MF: The trouble with The Searchers is that it’s so caricatured.

PP: It’s very mythical.

But the film doesn’t recognize that quality in itself, whereas Ford’s sequel to The Searchers, Two Rode Togetherwith Stewart in the role paralleling Wayne’s, is aware of that. Mann doesn’t sentimentalize Stewart’s bitterness, as Ford does with Wayne’s.

MF: In a Ford movie, the star is always in the center of the screen telling you what the point of the scene is, the camera’s always upshooting, and these beautiful physical specimens have all this leisure time to glory in being themselves—John Wayne or Jimmy Stewart in lousy costumes. But Mann is able to get the character off the center, somewhat peripheral, toward the edge of the screen.

In The Far Country, four people are on a porch. Two guys go offscreen. By just having them go offscreen, you have the sense that there’s a kind of wilderness out there; anyway, there’s a three-dimensional element. And that filters Stewart off-center even though he’s in the center of the screen.

Whereas in Ford, they’re like stamps—George Washington, they’re right there, they’re not going to move an inch, and you know Ford doesn’t give a flick about the country out there, that’s why he used those goddamn mesas over and over again: it hid the fact that he couldn’t care less about the West. It was an escape hatch. He has no curiosity about land or ground. When he shoots Stagecoach you’re inside the stagecoach: there’s nothing out there.

Mann uses matte shots, but he’s very clever: he gives you the sense of what’s around the matte, the frame. When I look at a painting, I’ve always been obsessed by what’s around the painting. So I’ll always go up and look at what’s behind the picture. Mann creates somewhat that effect too; there’s a lot of space around the edge; you could just pick up the corner of the process screen and… But it’s more ingenious than that, actually. His deployments are very clever. That Chilkoot Pass scene: that crazy column of hikers goes up the cliff like this: I wonder where that was shot.

It’s the same way in The Gold Rush—some documentary-like insert shots of people anting their way over a mountain of ice.

MF: I’d forgotten, that is straight out of The Gold Rush. But it doesn’t work in the Mann because it’s so artificial.

Stewart practically conducts the porch scene. He doesn’t quite make it work, he makes it too cute, but off and on through that movie, he has to make all the parts fall together with his face and the sound of his voice and the way he finishes a line. If he doesn’t finish it just at the right moment, the scene looks worse than it actually is; there’s practically no one else acting in the movie. Mostly, he’s making the writing work. Telling his two pals to leave him and the girl alone, that this panning for gold on the porch is going to take a long time—that’s a terrible line. It’s also a terrible action: two guys have to get up and walk off- screen.

PP: It’s odd again: the porch seems too shallow; people seem too big for that little porch, and the camera’s too close. It’s awkward.

MF: Absolutely right. And the porch doesn’t go with the saloon—it’s inconceivable that you’d walk out of a saloon onto a porch like that. And the porch looks like it was built that day, and like all porches in western movies, they build ‘em with four-by-fours and two-inch planks so everything is too tight, too short, too chunky.

PP: There are a lot of scenes where the camera seems uncomfortable, just a few feet too close. It has a feeling of claustrophobia.

A lot of Mann’s films are composed claustrophobically. His frames are designed to make you feel pushed, concentered too much. At the same time, he uses diagonals to lead lines out of the frame—that energy makes you see things being pushed out different ways.

MF: I’m not sure about that. The position of the camera is problematic.

PP: But remember where Brennan comes into the stateroom with stew and coffee? I know if I were going to sit down to eat, I’d feel very uncomfortable if 1 had to sit with my back against the bunk with another guy lying right next to me.

MF: But you feel the camera’s in a funny place in relation to the action. And the question is: is it being done for pressure and claustrophobia or is it being done because Mann hasn’t time to get a better angle on it, or because the scene is preposterous to begin with? How would you put a camera in front of a stateroom filled by three hopeless actors with improbable reason to be in the cabin at that time of day?

PP: I felt the same way about all the shipboard scenes. When the two stewards are coming toward him and he knocks one overboard—they’re too close to him not to catch him. The boat is too close to the deck for them not to be able to hand him over. And the stateroom is too close to everybody for him to be able to duck in there and get away. It’s all very improbable, spatially. These are funny things for someone who has a great concern with space—to make space highly improbable. Is he trying to test your credulity all the time, or is he spatially awkward?

MF: The boat’s too small, there’s no way they can fail to catch Stewart…

PP: All the way from Seattle to the Yukon.

MF: But the way he swings on the guy is very good and brutal, yet it’s totally unbelievable that a guy in that narrow space could get that much of a swing and hit someone that hard, hard enough to knock him over a railing.

One of the problems with genre movies is that criticism has gone wrong in crediting a scene like that to the advantage of the director, claiming that it’s a cunning handling. Whereas the writing of the scene is impossible. The probabilities of human nature in that scene are impossible as they’ve directed it. There’s no way the scene can be made to work—although it does work, actually. I think the camera is in the right place: all the spacesare too close. Stewart’s swing is very good and Stewart’s acting is too, so the scene works. My point is that the scene is impossible to begin with, so you couldn’t space it, decor it, build it, direct it so that it looks right; there’ll always be something out of whack.

Out of whack because it doesn’t tally with real behavior or out of whack because it doesn’t have the logic for its stylization?

MF: The logic, mostly. Intellectually, it’s illogical. A style couldn’t suture or bring together the illogic of the writing.

The thing that intrigues me most these days is why the person did it, and what it was between Borden Chase and Anthony Mann that would ever have gotten them into that stateroom or onto that back porch.

How do you answer those questions?

MF: I wish they were around. I have a hunch it never involved such ingenuity as we credit them with.

PP: People often say my paintings look tilted; the people are slightly off-balance. It’s true. I’ve done pictures of birds, and they’re all leaning at odd angles. I’ve never intentionally decided to make them all lean, it’s just something I do anyway. My point is that I don’t think everything is intentional. It doesn’t matter anyway, because it’s still there. Whether it was intended to be there or not, it’s still one of the elements that has to be dealt with.

Do you feel that these American films are more complicated, or more superficially complex, than the Oshima-Snow-Fassbinder films you’re interested in now?

MF: I used to, but…. I was going to say that I used to think it was the reverse, and the reason I got excited about Snow and Straub and Duras is that they were so hard to figure out, they were intellectually difficult. I still think they are. But I’m also being attracted back to the Hollywood movie by the technique of movies like The Far Country—a kind of limberness and intricacy I find exciting to look at. Pictorially.

PP: Also, there was a point which had to do with that poll of British film people Jonathan Rosenbaum did [Film Comment, November-December 1976]. It sounded like such heavy going, seeing every film through this text or that one—just fatiguing. Sort of: let’s all go back to school for twenty years and then we’ll he ready to start watching movies again. We’d have to start at the beginning.

Whereas you’re committed always to the individual film as the text, or at the very least, as the only primary text.

MF: Right. In the kind of criticism Patricia’s talking about, they’ll take a scene from Death by Hanging and get it down to the frames and how they read, and ask questions about why this frame was put in with that one, why this kind of material was put alongside another kind. It’s the same thing that bothers me about a lot of analysis of genre movies and why I bring up alternate motives and political ideas in discussing such films. It doesn’t interest me that much that the scene works because Mann and Stewart and Chase are able to divert the event into a new space, and that the space is so different from the space that the scene was heading toward that it’s refreshing to get into a different type of landscape—when you’re faced toward snow-covered mountains and suddenly Stewart says they’re going to spend the night in this declivity and the declivity is rather sunny and gentle, and I would think it might be a nice place to stop and spend the night. [The reader should know that despite his initial protestation at the beginning of this last sentence that it didn’t interest him much, Farber became progressively more interested in the example in the course of the sentence—a frequent occurrence].Or when the French girl is shoveling the sawdust for the gold dust, and she moves the pan back and forth, and you’ve got this hopelessly theatrical set-up with four people stuck on four feet of space with nothing to do but talk.

PP: And stare into the barrel.

MF: At least you get this slurry moving back and forth. It’s a diversion which has all kinds of attraction—in space, in material, in the kind of atmosphere that pan is going through and the way her wrists look as they make that move, and in Stewart’s frivolity, his mouthing of lines, the way he’s saying the lines referring to the gold. What a student thinks when he sees the scene is, “What’s at the bottom of this scene?” Is the ingenuity at the bottom of the scene, or is it an asinine idea to get them out on the porch? If it’s asinine, why are they being so ingenious about it? The thing that attracts me is the point: what it’s about. Why are they dealing with this subject, and is it silly, and if it is silly, why are they being silly to deal with it, and if they have no interest in gold dust, why are thy doing it? What are they trying to divert us from by showing a scene on a back porch with four people fooling around with a saucepan?

You’ve got good students.

MF: No! I think anybody looking at that scene has to face these facts. He’s not interested at all that it’s very attractive and ingenious as it’s worked out. He takes that almost for granted, that anybody that’s going to spend that much time and money on a back porch has to be pretty cunning. You can’t be dumb in a scene like that; anything you did would be better than what’s written. Taking that for granted, he wants to know who chose that actress and what was the point? Why did they put her in that little skirt? Who taught her to speak the English language that way? Why is Jimmy Stewart—a philosophic million-dollar actor—going through all this meshuggener stuff, putting up with Jay C. Flippen and Brennan—they’re all ganging up on him—what are they all fooling with the story for? And that is what an average customer says when he looks at The Far Country on TV.

And how do you go about looking for the answers to such questions?

MF: I think there are a lot of answers. First, if you accept the fact that it’s stupid, then it becomes interesting: I think if you asked Jimmy Stewart that, he’d probably come up with a good answer.

I want to know the ideas, what the content actually means. Why are we looking at this goddamn scene? I don’t care about his style, I think it’s immaterial. I think if the scene reversed itself—if the two people who went off stayed put instead, if the French girl, rather than shaking the pan, went back into the saloon and Stewart took out his knife and started whittling on a piece of wood and said, “What do you think about your chances of finding some gold?” something like that—the scene would have played just as well, and had its magic.

It wouldn’t be any dumber and it wouldn’t be any smarter?

MF: What I’m saying is: the ingenuities are almost all automatic. You couldn’t play that scene without turning it into magic. Because the camera’s there. If you put a camera in front of anything in human affairs and provide some stupid lines, it’s gotta be magical.

You’ve had too much Godard.

MF: That’s not true: I’ve looked at that scene too long. I’ve also been reading Stephen Heath talking about scenes like this frame by frame, never mentioning the character or what it’s doing; or if so only in the most succinct fashion—this Japanese boy was convicted of some crime and he was hung but the hanging failed so they had to prove that he was still alive so he could feel the evil so they had to jog up his memory and they took him out into the landscape and took him over these details when this little cat happened into the scene… The material that the scene is about is dragged in quickly, then gotten rid of. Then they talk at length about the frames and connections.

I had to explain my paintings to a seminar. I made my first step: I said, “I put this cracker here . . .” and I said inside myself, “I’m not going to go through this, this is stupid. They’re looking at the picture—how could they fail to see that the cracker is next to the box, and the box is next to the candy bar; and they’re all lined up. Tell them, ‘This is why I did it: to line them up’?” I couldn’t do it.

For the last class meeting, I was explaining to them why the class was a failure, and some of the students were making suggestions on how it could be improved. Two students thought I could have fixed up the class by using more slides of paintings and photographs to illustrate the movies. I answered, “I’ve lost faith in slides.” I’ve been able to lecture for three hours on one slide, and that’s how I prefer to teach slide lectures: use one slide and keep looking at it. I don’t see what the slide has to do with the movie—I can’t connect the two. I’ve also lost faith in analyzing positions and spaces in a slide: “The reason Jimmy Stewart is going that way is that Anthony Mann wanted to divert the space, he wanted to change it. . .” And I think to myself, that’s for the birds, he’s not doing it for that reason. But possibly he did, but there’re also other reasons—maybe he was up in imitation Alaska for other reasons—and I want to know the reasons. I want to know why they built the porch that way, and was it the custom to build porches that way?

How will you find those answers? Or is it important to find them? Is it rather that speculating on them in an analytic way is the important thing?