Abstract

Godfrey Reggio’s non-verbal film Koyaanisqatsi can be seen, in retrospect, as a pioneer both of the emergent environmental film genre, and of certain tropes of visual narrative that have come to dominate popular culture. This essay argues that the film articulates a critique of the inability of “anti-natural man” to distinguish between the “natural” and the “artificial.” My close reading of the film has four broad claims or theses: 1) In contrast to descriptions of Koyaanisqatsi as a “non-narrative film,” I argue that it has a non-logocentric narrative structure, which is laid out through an analysis of patterns of repetition of visual tropes; 2) Koyaanisqatsi revisions the human-nature relationship; its critique of modernity-as-machine makes gestures towards, or prefigures, ecocriticism; 3) The film has a quasi-religious discourse meant to unveil the “narrative potential” of nature, and the human-nature relationship (hence Reggio’s claims about a “better narrative” which “can go directly into…the soul of the viewer”); 4) The avant-garde techniques pioneered by Koyaanisqatsi are a cornerstone of environmental film, and an important moment in the “visual turn,” which challenges traditional notions of reading and literacy.

“What better narrative than that which can go directly into the sensibility and hence the soul of the viewer?” (Godfrey Reggio, in “Essence of Life”[1])

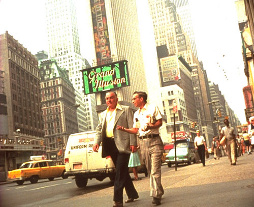

This reconsideration of Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi looks back on almost three decades of public life. The film’s U.S. premiere was at Radio City Music Hall in October 1982. On VHS, the film became a cult classic, but went out of print in 1992. Koyaanisqatsi’s pregnant silence in the following decade seemed to add plausibility to the hype MGM put on the 2002 DVD re-release: that Koyaanisqatsi “redefines the potential of film-making” (The Hollywood Reporter), and that it is “one of the greatest films of all time” (Uncut).

……

The initial reception of the film was mixed, but since the National Film Preservation Board chose Koyaanisqatsi for special recognition in 2000, critics are coming to see the film as a template for an emergent genre of environmental film.[2] As “the first full-length commercial nonverbal film”[3] , its enormous influence in the field of visual narrative has been increasingly recognized. Drawing on theories of visual narrative, the second wave of ecocriticsm[4] , the director commentary and other features on the DVD, and interviews Reggio has done in conjunction with the completion of his Qatsi trilogy, my close reading of the film has four broad claims or theses:

1. In contrast to descriptions of Koyaanisqatsi as a “non-narrative film,” I argue that it has a non-logocentric narrative structure, which is laid out through an analysis of patterns of repetition of visual tropes;

2. Koyaanisqatsi revisions the human-nature relationship; its critique of modernity-as-machine makes gestures towards, or prefigures, ecocriticism;

3. The film has a quasi-religious discourse meant to unveil the “narrative potential” of nature, and the human-nature relationship (hence Reggio’s claims about a “better narrative” which “can go directly into…the soul of the viewer”);

4. The avant-garde techniques pioneered by Koyaanisqatsi are a cornerstone of environmental film, and an important moment in the “visual turn,” which challenges traditional notions of reading and literacy.

In most concise form, my unifying thesis is that Koyaanisqatsi articulates a critique of the inability of “anti-natural man” to distinguish between the “natural” and the “artificial.” These terms will be defined and developed.

“New Nature” and New Narrative

In the chapter “Other Cinematic Shapes: Documentary and Experimental Films,” from their book The Film Experience, Timothy Corrigan and Patricia White describe Koyaanisqatsi as an exemplar of “non-narrative” experimental film. Their definition of this mode of filmmaking as one that “eschews or de-emphasizes stories and narratives, while employing such other organization forms as lists, repetitions, or contrasts as the organizational structure” is accurate enough, on the surface, but seems to employ a logocentric definition of narrative. David Bordwell, amongst others, has recognized the potential of visuals and sound to create narratives, even in the absence of words (Narration in the Fictional Film, Routledge, 1986). Susan Hayward defines film narrative as such: “Narrative refers to the strategies, codes and conventions (including mise-en-scene…) employed to organize a story.”[5] This leaves plenty of room for the sorts of audio-visual narrative strategies I am about to analyze. But a certain residual narrative/ non-narrative binary remains in film criticism, which I wish to interrogate. This binary is evident in the comments by Corrigan and White about Reggio’s film: “Through these images one may detect traces of a story about the collapse of America…but that simple and vague narrative is not nearly as powerful as the emotional force of the film’s accumulating repetitions and contrasts.”[6]

These gathering repetitions and contrasts do indeed have a “powerful…emotional force,” but they also have a narrative logic. But uncovering or deciphering the film’s particular sort of narrative requires confronting a residual logocentrism in film criticism. Even sympathetic viewers are prone to describe Koyaanisqatsi as a “plotless, characterless and dialogue-less journey.”[7]

“There is no film theory,” wrote Al Razutis in 1984, “that is adequate to the needs of the many film avant-gardes.” Razutis was criticizing psychoanalytic critics who opposed “non-narrative” film. This debate occurred around the time of Koyaanisqatsi’s release; it indicates that the visual turn was contested by film critics invested in logocentric definitions of narrative. At the New Narrative Cinema and the Future of Film Theory conference, Kaja Silverman argued that “experimental filmmakers [had] repudiated narrative.” In response, Razutis described film theory’s incomprehension of avant-garde film as “compounded by the prevailing assumption… that narrative cinema represents the true cinema of culture. Thus the marginal status of…avant-garde films is largely due to their inability to ‘invest’ in narrative.” I find Razutis’ assessment of the “literary preconditions” of “new narrative” theory relevant to the present discussion: that it “inherently define[d] the imagistic and musical as ‘not words’” – and hence, non-narrative.[8]

To conflate words and narrative is to set up a false opposition between word-based story-telling and the visual narrative through which a film like Koyaanisqatsi conveys its connotative storyline[9] . The narrative capacities of images had been recognized by narrative theorists long before Koyaanisqatsi’s release. Roland Barthes hoped to “emancipate narrative from literature.”[10] How could literature “hold narrative captive,” one might ask? Implicit in such an emancipatory project is the notion that the “enchanted forest of literary criticism” often marginalizes non-traditional narratives.[11] Freeing narrative from its logocentric shackles, then, is a utopian project: an effort to achieve “whole sight,” to free oneself from “slavish adoration” to The Word.[12] During the transition from the “discursive turn” to the “visual turn” in the social sciences and the humanities, new meta-narratives have emerged which may seem most comprehensible in visual form – such as in Reggio’s case, “the limits to growth,” or “living in technology.”

The function of narrative has been defined as “a tool for constructing models of reality”. More broadly, “narrative creates and transmits cultural traditions”; and is “a mirror in which we discover what it means to be human.”[13] Clearly both sound and image can serve those purposes. As Ryan argues, narrativity cannot be limited “to verbal texts nor to narratorial speech acts.”[14] Recognizing the importance of visual narrative in film is part of a re-defining of narrative: it evokes not just a sequence of events, but the larger world in which these events take place.[15]

Objects in the natural world have a “narrative potential” – the capacity to spark a response in the mind of the viewer that involves a form of story-construction. Viewers construct stories out of all sorts of visuals: planes flying into buildings; the iconic moon “colliding” with a skyscraper in Koyaanisquatsi, etc. Objects “possess narrativity”[16] and can inspire a narrative response in the viewer, often independent of the narrative that the “author” of the image had in mind.

Reggio speaks of “a ‘trilectic’ relationship of image, music, and viewer” in his work. In meaning construction, visuals, music, and the “eye of the beholder” have equal value. Reggio has said clearly that his narrative intent is to reveal how technology has become our “new nature,” which has “separated us completely from nature.” His reliance upon image and music in order to leave interpretation open-ended is intentional. Hence, in the “Essence of Life” interview Reggio observes that “for some people, [Koyaanisqatsi is] an environmental film. For some, it is an ode to technology. To some people, it’s a piece of shit.”[17] The mixed responses that Reggio encourages are evident in Claude Lalumière’s confession that he saw “splendor” in Reggio’s representations of the city, whereas he suspected that the director only wanted him to see “ugliness.”[18]

“Humiliated” Language and the “Communion” of Image and Sound

Reggio’s comments about a “better narrative” (in the epigraph above) came in the context of his discussion of how the cinematography of Ron Fricke and the music of Philip Glass were two primary ingredients of his cinematic attempt to “go directly into…the soul of the viewer.” He described the result as “something more akin to direct communion than going through the metaphor of language.” Reggio insisted: “It’s not for lack of love of the language that these films have no words.” Rather, “from my point of view, our language is in a state of vast humiliation. It no longer describes the world in which we live.”[19] The language used by many politicians, lawyers, journalists, and religious leaders has so distorted or masked reality that language often seems to have been evacuated of its truth-telling capacity.

The crisis is not merely that the use of words to disguise meaning has become normative. Science and technology have “uprooted language itself and made it unreal,” asserts Bruno Thibault. “The universal crisis of language is the major event of our time,” he argues.[20] Reggio has been a cinematic pioneer in thinking through the consequences of this devaluation of language: if words are so humiliated that they only serve to mask the reality of the world we live in, then another form of communication is called for.

Reggio’s reference to communion, and his distrust of language, express concerns that grew out of his decision, at age 14, to leave New Orleans and enter a monastic order in Santa Fe. Within what he called a “medieval” existence in northern New Mexico, Reggio lived a life based on prayer, meditation, and manual labor for most of the next 14 years. This meditative life in the desert Southwest help explain how Reggio developed a communion-like narrative form.

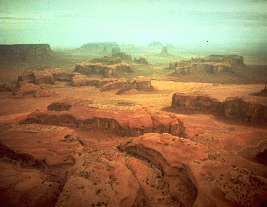

Asked how this influenced his filmmaking, Reggio replied that he was “always interested in and motivated by what stands behind the surface of things.” In the Southwest, he devised an approach to film-making that would “take the background and make it the foreground.”[21] For example, the Monument Valley Navajo Reservation, backdrop for so many westerns, was foregrounded by Reggio. In popular culture cities are often named as if they were a character (L.A. Law; Sex and the City; NYPD Blue), yet are really just ambience for human dramas. But the cityscapes these examples show in passing, Reggio “blows up” into icons which are slowed down or sped up in his trademark manner, to make us see the personality of this “backdrop” with new eyes.

Reggio was “seized by this idea of social justice” from a young age. While in New Mexico, he saw in Luis Buñuel’s film Los Olvidados (Mexico 1950) a model of the portrayal of injustice (or the unveiling of the causes of suffering) as the heart of a true spiritual vocation. Reggio says he showed this film some 150 times to gangs in the Southwest.[22] This concern with social justice was developed through the Institute for Regional Education. Beginning in 1974, he made short public service films about the uses and abuses of technology in the invasion of privacy. Through this work with the IRE collective, Reggio met cinematographer Ron Fricke. Together, around 1978, they began working on what would become Koyaanisqatsi.

Reggio came to believe that images would be more effective than a devalued language in revealing “the main event of today… the transition from old nature or ‘the natural environment’ as our host of life for human habitation, into a technological milleu – into mass technology as the environment of life.” All facets of contemporary life, as Reggio sees it, “exist within the host of technology. It’s not that we use live technology.”[23]

Koyaanisqatsi is about the “terrible beauty” of technology, in Reggio’s “short description,” or the “beauty of the beast. That which we are most proud of. Our shining beast.” This affixing of “Beauty” to the technological city as well as to nature may be a way of partially masking the perception that Reggio is “something of a Luddite,” as Michael Dempsey wrote.[24] Koyaanisqatsi can be situated within a tradition of the “city symphony films,” visual poems such as Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (Germany 1927) and Man with the Movie Camera (Russia 1929). Reggio’s use of avant garde techniques which “let people see what they usually could not or would not,” as Patricia Aufderheide writes, shows the influence of this tradition.[25] Reggio fuses that sensibility with an environmental consciousness and spiritual training. One of the reasons for Koyaanisqatsi’s success, argues Scott MacDonald, is that “he had been able to exploit a form of viewer pleasure most commercial and critical cinema has ignored: he has been able to invest this pleasure with a spirit of social concern and spiritual mission.” Reggio clearly had audience expectations in mind when he told Michael Dempsey: “The Beast doesn’t come as a baglady, it comes as a seducer, it comes bejeweled.” [26] This worldview, however Biblical and medieval it may be at root, is in tune with a long and rapidly growing genre of apocalyptic film.

Beginnings and the “Beautiful Beast”

Walter Benjamin famously commented that humanity’s “self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.”[27] Reggio is part of a history of cinematic pleasure of observing our own destruction. In a 2005 interview after the release of the most dystopian of the Qatsi trilogy, Naqoyqatsi: Life as War (USA 2002), Reggio admitted: “collapse, dysfunction and disintegration could be a blessing in disguise.”[28] However, when Michael Dempsey suggested in 1988 that the contrast between beautiful nature and dehumanized people in Koyaanisqatsi inferred “a half-acknowledged fascination with the notion of wiping out the human race,” Reggio dismissed that as a “projection.” He told an interviewer in 2002 that his attempts to “raise a flag to the blinding light of technology” were meant not “to depress, it was to purge.”[29] But there is no denying that Reggio shows what seems like pre-human landscapes, and then infers a possibly post-human future.[30] Dempsey described the opening half hour of Koyaanisqatsi as “almost as though we are seeing not Earth or even a stylized view of primeval Earth but another planet altogether.” Reggio himself has said recently: “I’m trying to look at this world as if an alien appeared and was trying to make some visual if not emotive sense of what they encounter.”[31] That visual sense, he said in the Film Quarterly profile, was “to show the earth unrelated to man, having its own grandeur, having its own consciousness.”

Koyaanisqatsi, then, participates in a standard trope of environmental film, representing the earth as a character with “a life of its own” and a sort of volition independent of humans. Reggio’s narrative can be summarized as such: the “beautiful beast” of technology has separated us from nature to the point that now technology is our new nature – or as Reggio has said in most compressed form, the (previously invisible) transition from anima mundi to techno mundi.[32]

My reading about the interface between humans and nature proceeds from the first image: an Indian pictogram at Canyonlands Nation Park. In this supposedly pre-human landscape, humans and their king were present, defacing or enhancing nature, as was already clearly their second nature, with an early technology. Starting at 0:50 of Chapter One (“Beginning”), a shot of the Indian cliff art is held for a minute, beginning in close-up, then pulling back to reveal the full portrait in which a larger crowned King dominates his subjects. Suddenly, a fiery explosion wipes away the image of the Indians and their pictographic ruler.

The slow-motion inferno billows and then fragments are seen falling, almost snow-like, until the base of the Saturn V rocket of the Apollo 12 mission begins to become visible. Finally the rocket begins to lift, and at 3:48 there is a flash of light, which quickly fades into an aerial shot of desert badlands, with long shadows just before sunset, which is the start of the second chapter, “Organic.”

“Beginning” refers in part to Genesis.[33] But it also points to the roots of human culture as image-making “symbolic animals.”[34] The Apollo launch symbolizes the origins of manned space flight. Hence, in a broader sense this segment refers to the origins of human efforts to literally leave Mother Earth. The technological humans here employ a mighty fire capable of wiping out traditional cultures, amongst other resources that are burned up by our conquering of the frontiers of nature. By the end of the film we will be told, visually, that “what goes up, must come down.” But in the beginning, viewers may not notice the ways in which this great fire seems to have wiped out indigenous peoples – or perhaps, as meta-narrative, the whole of human civilization.

The utopian pastoral images for which the film is famous only occupy 12? minutes (3:50-16:24). The beginning of Indian art, fire, and the launching of space rockets should prepare the viewer to look at the beauty of the following “empty” landscapes with the knowledge that humans have been present for millennia in these lands, have shaped them in profound ways, and in their worship of “false gods,” created the technologies which are capable of laying waste to these lands.

The cumulative narrative logic of the film develops through repetitions and contrasts. “Organic” not only provides contrast to techno mundi, but also suggests certain parallels and indeed inter-penetrations between anima mundi and techno mundi, which become more explicit as the film progresses. An early aerial shot of the canyonlands just before sunset highlights rock ridges and a pattern of shadows that seems to prefigure a match cut at the end of “The Grid,” between an aerial view of Manhattan canyons, and a

computer chip. Other visual motifs are introduced, on which Reggio will play variations. There is a contrast between phallic rocks, and circular openings in the earth. In early scenes Reggio shows idyllic images of light entering through cave openings, and mist or bats going out of what, as the camera pans in, seems to suggest a womb or vulva of the earth. This will later be set in relief with stock footage of phallic rockets emerging from openings in the ground.

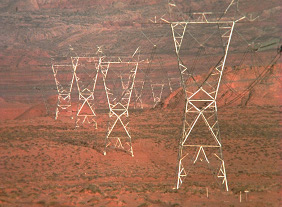

Several visual tropes are introduced that point to underlying patterns shared by nature and human society. One is trinity-like formations. We see three rock pillars framed against a sunset; later the same framing will be used for three smokestacks of the coal-fired power plant, and three skyscrapers. But I think the most important “guiding motif”[35] introduced here is energy-in-motion. Both the earth and its people move in inter-connected ways, the visual narrative suggests. The motion and energy of the earth feeds and structures human societies like a grid, so that people and the systems they construct often seem to mirror, or echo, the flows of nature. Reggio does not merely repeat the images of nature’s movement in order to set up a contrast with the movements of human society. He begins to demonstrate how patterns of energy-in-motion repeat or replicate themselves. The energy of first nature is transported to and translated into the city symphony.

At 9:30 the motion of sand blowing across a sand dune appears similar to the motion of mist we have seen previously. This in turn looks much like the motion of water moving over a falls, which is shown shortly afterwards. Glass’s score accentuates the increasing complexity in the visual narrative. Horns enter at 10:06 as the scene cuts to clouds and their shadows moving over canyon lands, where we see green for the first time. This segment seems to suggest how water, wind and earth work on each other, producing new life.

In Chapter 3 (“Clouds”), the visual narrative concentrates on the power and majesty of the forms water takes, and the ways in which water moving across the earth seems to set a template for the movements of people in the great cities. We see the roiling of thunderstorm clouds rising, then a waterfall, and then slow-motion shots of powerful ocean waves, and pointillistic studies of the play of light on the ocean surface. The ocean (and generally water) becomes a living thing where it meets air and light, especially as guided by the earth’s structure. We are shown a correlation of the form of ocean waves falling, and a river cascading, and then even mist running off cliff edges takes the same form as the waterfalls or the waves.

“Resource” moves from nature into the realm of humans. Connections are denoted, showing how the power of nature energizes human societies, with results that are often both catastrophic and beautiful. Even the fall of earth after a mine explosion suggests the flows of water or mists in prior scenes. But then an ominous, martial music accompanies images of pipelines carrying coal to massive coal-fired power plants, and the march of huge power lines across the horizon towards the cities of the west. We begin to understand the underlying logic of the title of Reggio’s film.

“Music To My Ears”: An “Aliterate” Critique of the Insanity of Techno Mundi

Koyaaniqatsi in Hopi means “life out of balance.” Reggio provides several translations for this word at the end, including “A state of life that calls for another way of life.” Reggio recalled: “I originally didn’t want a name for the movie, but an image. Why have a word for something unnamable?” Calling language inadequate to describe techno mundi, he elaborated: “Koyaanisqatsi was a word that had no cultural baggage, from a culture that was aliterate, that held everything we called normal to be abnormal and sane to be insane. That was music to my ears…”[36]

Reggio’s suspicion of word-based literacy is again evident in his depiction of Hopi culture as “aliterate.” An “alliterate” person “can read but is disinclined to derive information from literary sources.” Aliterate cultures place high value on sources of information that do not come in written form. Hence, they tend to rely heavily on oral culture; they are attentive to visual narrative; they read nature directly, etc. This is part of what seemed “music” to Reggio’s ears. But his comments also reveal something else about the nature of the narrative in which Reggio is invested: a history of idealized, or romanticized representations of both tribal peoples, and of nature itself.

The use of indigenous cultures to invert the values of “the over-developed world” has deep roots in romanticism, and later in modernist, post-modernist and post-colonial thought. When Reggio uses a Hopi word to describe Western norms (unlimited growth as an abnormal “ideology of a cancer cell”)[37] as “insane,” and describes this worldview as “music,” he is following a well-trod narrative trajectory. The list of writers who have used other cultures perceived to be living in nature as mirrors in which they can see the shortcomings of their own culture is enormous. This would include Rousseau’s “Noble Savage,” James Fenimore Cooper’s “white Indians” of the U.S. revolutionary era, Mark Twain on the Mississippi, C.G. Jung in Kenya and in New Mexico; D.H. Lawrence in Taos and Mexico; J.M.G. Le Clézio in North Africa, Panama, and Mesoamerica, etc.

The “ecological Indian,” or the idea that “in the New World…man was in harmony with nature,” has for centuries been at the center of the dreams of Europeans and Euro-Americans who sought to critique what their own culture had become, and to imagine a more natural alternative.[38] Reggio signals his narrative’s outline with the title, with the images of indigenous art with which he chose to open and close his film, and by contrasting that indigenous framing device with fiery explosions of ascending and the descending space rockets.

As the first of a trilogy, Koyaanisquatsi portrayed the post-industrial north. Powaasqatsi (USA 1988), second in the trilogy, viewed the developing south in transition towards techno mundi. All the footage of the first film was shot in the U.S., but the images are not a specifically national critique. Rather, the U.S. offered the most dramatic contrast between the frenetic cities, living completely within the host of technology, and the “primitive” hinterlands from which the energy for the cities was taken. Hence, the film visualized how far the dreams of technological “anti-natural man” have strayed from that dream of being “in harmony with nature” (including human nature).[39]

What Reggio sees is presumably like what his hypothetical alien would see: the worship of technology, and people everywhere enthralled, contained, and restrained by their technology. This comes across in a variety of ways: an enormous mining machine that dwarfs its operator sitting in a cabin, far above the earth; shot after shot of people enclosed within the machines that transport them, planes, trains, and especially cars; and the “vessels” (in the title of Chapter 5) themselves enclosed within grids that pre-determine almost all human movement.

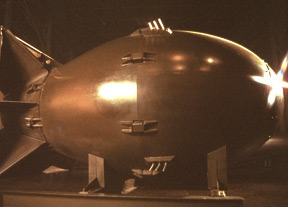

The sense that humans are in thrall to a technology that has the power to enslave or destroy them becomes more explicit as the images move rapidly from coal, to oil derricks and tanks, to nuclear power. The chapter ends with footage of an atom bomb test over the Nevada desert. Typical of repeating images of nature and techno mundi in inter-related proximity, the rising of the nuclear mushroom is framed by a yucca plant in the foreground. As this symbol of humanity’s God-like power to destroy the earth rises up, the music fades; at 23:00 there are a few seconds of silence. This is the first of several instances where Reggio uses silence like a musical notation: like “Selah” in the Psalms, a cue to “stop and meditate.” The silence prods us not only to think more deeply about what we have seen, but to prepare us for what is coming: syntagmatic connotation.[40]

The image following the nuclear explosion is sunbathers on a dirty beach. They doze as if dead: this is the culture that the nuclear techno mundi has produced. The camera pans up to reveal the San Onofre nuclear power plant, and cuts to a crowd of people looking up with rapt attention towards the horizon: perhaps on a tour of the nuclear power plant. The mostly white-haired, entirely Caucasian onlookers, many clad in plaid, could be straining their necks up towards the following image: an almost vertical shot of a skyscraper, its neat square windows perhaps echoing the prior plaid and certainly foreshadowing the coming visual essay on “the grid.” On the blue surface we see the reflection of clouds passing. This is the first instance of another repeating visual motif: the gaze towards a nature that only (or primarily) appears in the reflection of the city.

Or perhaps Reggio is preparing viewers for what follows: United Airlines Boeing 747s slowly materializing on a runway. The preceding scenes, and the music, give us cues as to the rationale of this long take. Several examples of human worship of technology have already been shown, especially in gigantic form. Now heavenly voices accompany the slow tracing of the planes that, over the course of three minutes, move gradually into focus, and turn onto a runway. The powerful telephoto lens reinforces the gargantuan, other-worldly nature of these “vessels,” as if they are gods who have materialized from the heavens, bringing their human cargo.

Then accelerating repetitions of and variations on two recurring themes commence: humans enclosed within the grid of the technology they have created, and this technology’s power to create and destroy on a scale previously only possible for deities. Traffic is central to the visual narrative of entrapment: another telephoto shot reinforces the isolation of individual drivers. A taxiing aircraft enters the frame, behind the traffic, as if to underscore that visible movement – planes, humans, and cars – is structured by the same controlling grid. An aerial view shows cars on a freeway clover at regular speed, but the music is accelerating. The remainder of the film will reinforce that the pace of modern life, and the structure of that life, are dehumanizing, and yet completely “second nature” for technological humans.

In this segment, the ideological subtext seems clear, although Reggio has insisted that he “did not wish to engage in overt propaganda.”[41] “Vessels” ends with an over-head shot of an aircraft carrier, with E-MC2spelled out in white on the deck. Between the city traffic and this startling image, an escalating series of images indicate the militarized nature of this society, leading to mass destruction: an aerial shot of a huge car lot is followed by endless rows of Soviet army tanks, after which the narrative logic takes flight: an Air Force jet on a runway is followed by a shot looking down over the wings of a camouflaged jet flying over a barren desert; then bombs fall and phallic missiles shoot up out of the earth; a booster rocket falls and disintegrates. Throughout this sequence, there is a sense that this “life out of balance” has become unhinged precisely because it has been removed from the earth. The film takes technology’s point of view and looks down towards an earth that technology has been designed to re-order, or destroy. The cues are not subtle: after the falling rocket the camera approaches an atom bomb (a model of The Fat Boy dropped on Hiroshima). Just as the camera seems about to enter the belly of the bomb, the scene cuts to the E-MC2 ship. Yet the narrative logic of the visuals is partly undercut by the exhilarating score, which reinforces a sense that the events we are witnessing lead towards exaltation.

In cinematic terms, a sort of rapture follows: we see rapid-fire shots of military hardware being destroyed by bombs. A plane releases a cluster of bombs, which fall and ignite an apocalypse on earth. A viewer may glimpse a defamiliarization of the Christian rapture, wherein the chosen will be lifted up, and have ringside seats to observe the fiery destruction of the wicked and the heathen. More fiery explosions fill the screen. But this time, not in the desert, uranium mines, or Los Alamos, but in New York City. Suddenly, at the start of Chapter 6 (“Cloudscape”), Reggio cuts Glass’ score. The viewer sees time-lapse photography of New York from a great height, the diegetic sound originating from traffic far below moving at an accelerated pace, the high-speed clouds casting eerie shadows across a beautiful but “unnatural” cityscape. For 40 seconds, viewers are invited to “stop and meditate.” Presumably they see “the beauty of the beast,” but also, in context, the civilization that the previous instruments and acts of war are designed to protect.

The Nature of the City

Scott MacDonald has written that Reggio “reveals the modern city…as a gigantic machine and the human beings who live there as its moving parts.” For the most part, the city-machine functions with extreme efficiency and breathtaking beauty. Yet in contrast to commercial cinema’s homages to the city as a site of heroic individualism and ingenuity, Reggio’s beautiful beast excels in “the destruction of individuality and serenity.” Reggio’s implicit critique is not so much of the city itself, but of a cultural myopia: “our ability to blind ourselves… to the larger patterns within which what we call individuality is subsumed,” writes MacDonald.[42]

This big picture of Reggio’s narrative is a transfiguring of human nature via its transition into the new nature of techno mundi, and its entrapment within the grid of this brave new world. Several key repetitions and contrasts are further developed in Chapter 7 (“Pruitt Igoe”). The canyons of Wall Street are in stark contrast to the slums that follow. The music, now a classical elegy, indicates the tragedy of “The Wasteland” – humans trapped in inhuman conditions. The syntax of the move from Wall Street to Bedford-Stuyvesant suggests that these are the conditions “extreme capitalism” inevitably produces. The blight of abandoned projects half-buried in debris, and the eyesore of trash on slum streets, is heightened in contrast to the beauty of “Cloudscape” which preceded it. Above the skyscrapers, the viewer saw the glories of heaven; below now, a hellish underside. The narrative of entrapment can now be read on the faces of individuals looking out of their prison-like windows. The motif of flowing water returns, but this time it is a fire hydrant used to give relief to the poor in summer, and to wash away the trash on the streets.[43]

This chapter is dominated by fly-over shots and close-ups of the Pruitt Igoe projects. When Koyaanisqatsi was released, Pruitt Igoe was already a symbol of “the failure of modernist thinking and high-tech solutions to social problems.” 25 years later, an added layer of symbolism accrues to the sight of these buildings falling down (during demolitions 1972-74): a co-architect of Pruitt Igoe, Minoru Yamasaki, was later chief architect of the World Trade Center.[44] Accentuating the visual motif of “all falls down,” Reggio follows with footage of the dynamiting of a variety of structures: bridges, cranes at dockyards, high-rises. Once again, the screen is filled by the smoke and fire of the explosions, and then falling debris in slow motion, which refers back to the rocket launch in the beginning, and prefigures the slow-motion fall of debris at the end. Once again, the music is cut, precisely at the moment when the visuals transition from destruction to seemingly pastoral images. This time, there is still some faint ambient music in the background. But the effect is still a “Selah” moment – “lift up your eyes” and meditate on what you have just seen, “to let it get deep within you.”[45] But the nature that provides the backdrop of this meditative transition is now clouds moving over the city. This goes on for almost three minutes.

The first half of this interlude of high-speed clouds passing over the city is shot at a great distance; the city skyscrapers appear as an isolated outcropping. The clouds are dark, and at moments become thick enough to obscure the city completely. If the purpose of a “Selah” is “to punctuate the previous stanza,”[46] then the narrative function of this section must be to provide a necessary contrast to the preceding images of urban blight, and the “violent” demolition of human structures. Reggio seems to want us to understand the limitations of techno mundi – seen from a distance, both the glorious beauty and the destructiveness of urban environments seem relatively meaningless. The forces of mother nature dwarf the city. It is almost as if the moisture carried in these clouds is washing over the city, cleansing her of her sins of omission and commission.

But a “cinematic Selah” must not only clarify prior images, it must prepare us for deeper layers of meaning in the images that follow. The last half of this interlude takes a different point of view, suggesting different meanings. We look up towards skyscrapers and see the same clouds racing past, but now the buildings dominate the clouds, instead of being dwarfed by them. What has been low background music rises to the foreground; a bold synthesized horn takes “center stage.” Almost the entire screen is occupied by a massive

Microdata building, 32 offices wide. As with previous buildings in this visual trope, the sky and passing clouds are reflected in its shiny surface, the reflected clouds moving in the opposite direction of the “real” clouds. Once again, the neat rectangles of the shimmering surface suggest a grid, a central motif as the film progresses.

One might ask here: is this nature we are seeing? Some viewers will answer yes. However, all but a sliver of the screen is occupied by a building that acts as a mirror. So what is shown is actually a reflection of something like nature. Furthermore, even in the slice of the film image in which the “real” clouds move in the “correct” direction, we are of course not looking at the clouds themselves, but at an image projected on a screen. The surface of the Microdata building itself, furthermore, acts as a screen onto which the audience projects their own preconceptions about cities and nature. The multiple layers or levels which remove us from nature become apparent in this representation of reflected nature, which was originally recorded on film stock, edited and transferred numerous times, later “translated” to digital format, recorded onto DVDs, projected through a DVD player onto one screen or another. Finally in this form this optical illusion enters our retinas and is passed along as a signal to the brain, which is interpreted as nature. But what is left of the original? I think this is part of what Reggio hopes his viewers will meditate on. But he is less of a Luddite than some people suspect: on one level he is “enthralled” by the beauty of this image. His images contribute to a subtext, that the forms of our techno mundi continue to be interdependent with anima mundi, and are much more ephemeral than we realize. On yet another level, this narrative continues to explore the upside and the underside of the human-nature interface: the differences between how humans and nature appear when seen from above, and from below; in seeming isolation from each other, and in evident inter-relationship.

“Slow People” (#9) pays most attention to individuals, and actually uses words, although strictly as signs. These signs are not incidental elements of the urban background. They are ironic commentaries on the nature of urban life. The title refers to slow-motion footage of pedestrians in Manhattan. The music suggests the plodding of dinosaurs, as does the outmoded polyester dress of the pedestrians. They are mostly overweight, largely office workers wearily headed home. Behind the “organization men” crossing the street is a billboard for “Real” cigarettes which reads: “Taste the natural cigarette. Low tar. Nothing artificial added.” This continues the critique of the inability of “anti-natural man” to distinguish between the “natural” and the “artificial.”

Few of these urban dwellers look healthy, or happy. More dour people walk below a Colonel Sanders billboard: a smiling boy holds a mega-bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken, next to the words: “Have a barrel of fun.” These cityscapes are replete with ironies about the natural and artificial. On an electronic billboard, over a green and black background (trees), gold lettering spells out: “Grand Illusion.” Beside the curb, a van advertises “ST*R UNIFORM RENTAL.” Everyone in this world, it seems, is wearing a mask, a uniform, some means of maintaining an illusion. This perception is underscored by a creepy shot closing this chapter, a group portrait of six women in orange uniforms outside a casino. Most of them are well into middle

age, and three wear wigs – beehives and other unsightly styles of the era. Behind them the neon lights sparkle and move with their own characteristic flow. The music fades and we hear only ambient sounds of the city. The image seems to say: this is the reality beneath the glitter and the illusion.

“The Grid”: The Fabula of a Revolutionary Cinema

Let us return to Reggio’s notion of a “better narrative” that communes with the viewer’s soul. For many viewers, this film is a transformative experience: the film is commonly described in quasi-Rubicon terms, with pre-Koyaanisqatsi and post-Koyaanisqatsi worldviews.

One should bear in mind Reggio’s self-deprecating willingness to see other responses (“a piece of shit” or a hymn to technology) as equally plausible. Still, the accolades that this film continues to garner tend to describe Koyaanisqatsi as a sort of unveiling experience that fosters a new vision. “Starting with the title,” Andrew Gumbel wrote in 2002, “it was clear that Reggio was a film-maker like no other; that his project was nothing less than to look at the world through new eyes and invent a fresh cinematic language with which to express what he saw.”[47]

In “The Grid” this visual narrative reaches its climax, 22 minutes of revolutionary cinema. Here, Reggio and his collaborators successfully challenge logocentric concepts of narrative, indeed “redefining cinema’s potential” to open our eyes to the greatest story of all: “life on earth.” That had previously seemed too grand to render cinematically; too abstract for film genres. But in retrospect, one can see that Reggio pioneered an iconic way of looking at both the natural world and the modern city as having “a life of its own” that has now become almost commonplace.[48]

Seeing innovations such as high-speed traffic replicated in contemporary advertising and film has somewhat dulled the freshness of the original. But over a quarter of a century after its release, Koyaanisqatsi still can have a transformative effect. As it accelerates it conveys the sense of being born upon a river of energy, which can be disorienting. Losing one’s illusion of individual autonomy is at the core of most “altered states of consciousness,” whether achieved through spirituality or otherwise.[49] This director’s ambition to inspire both communal meditation and critical consciousness of the limits of individualism in techno mundi helps explain the film’s long-term appeal both to “heads” (a “trip movie”) and to political progressives. The film heightens two seemingly clashing perspectives: an awareness of the wonder and beauty of urban life, yet also a consciousness of the non-sustainability of the current upon which one is born.

Seeking to understand this film’s power to “go directly into the sensibility” of viewers, and to hold differing worldviews in creative tension, let us examine the Russian Formalists’ distinction between the syuzhet (the plot or way of telling the story), and the fabula – the “big picture” inferences (metanarrative) we draw from the actual narrative.[50] David Bordwell emphasizes that the fabula is an “imaginary construct” created “progressively and retroactively” by the spectator. The fabula is not actually present in the film. It is “a pattern which perceivers of narratives create through assumptions and inferences.” This interactive process is much like a communion between film-maker and viewer, the latter “picking up narrative cues” supplied by the former.[51] Viewers apply their own schemata, or templates, which are inevitably are rooted in specific psychological and socio-cultural contexts, so each reader or viewer “introduces his or her own fabula.”[52]

As an “imaginary construct” the fabula is not less real than the “main story.” We do not claim that nationalism or racialism are unreal for being constructed.[53] But it can only be indirectly connotated: film-makers can point towards this big picture but cannot predetermine the way that spectators fill in the blanks, as it were. A film-maker can hope that viewers will make inferences believed to be suggested by the “reiteration” of key themes or symbols.[54] But making construction of the fabula possible involves a deferral of authority: one can almost speak of an act of faith that the viewer will connect the dots in a particular way. Recognizing that the fabula can only be suggested/ connotated is akin to Faulkner’s view of the power of artistic indirection. Drawing on the symbolist credo that “to name is to destroy, to suggest is to create,” Faulkner believed that “it’s best to take the gesture, the shadow of the branch, and let the [reader’s] mind create the tree.”[55] Telling the reader or viewer too much limits interpretation and forecloses the potential fabula.

Religious training, an environmental ethic, and sympathy for non-Western cultures are keys to the fabula that Reggio suggests. One can see a unique sort of religious symbolism in Reggio’s repeated use of “trinity” imagery – here

two shots of groups of three skyscrapers at night near the beginning of the grid. After seeing trinities in nature (rock towers) and in the conversion of anima mundi into techno mundi (the power plant’s smokestacks), one can “progressively and retroactively” infer a pattern that we now worship technology.

After the “Christ between thieves” skyscrapers, Reggio shows two different time-lapse shots of a setting orange sun reflected on the windows of a skyscraper, fading as it falls, then disappearing, as if the skyscraper has swallowed the sun. These skyscrapers that swallow suns and moons and burn up unimaginable quantities of energy are a form of palimpsest narration.[56] They dramatize just how far removed urban societies are from the power of the real sun, how dependent we have become on this unsustainable “ancient sunlight.”[57]

My reactions as a spectator to the iconic image of the “inflated” moon moving “into” a skyscraper are somewhat different from my analysis as a critic. Watching the rising moon “approach” the skyscraper always produces the visceral expectation that there will be a collision. The telephoto lens makes the moon seem gigantic, and produces the optical illusion of a coming collision. But the skyscraper appears the dominant object. The building obscures the moon. The moon is clearly the more lasting object, but our perspective of it has been defamiliarised. This image of striking beauty, and

the moon’s disappearance behind the tower produce a sense of astonishment. This shot lets us catch our breath before plunging into the vortex of dizzying motion and accelerating music to follow.

This is an elaboration of the prior visual motif: buildings swallowing heavenly objects. What follows, after the “dying sun,” is the introduction of the nighttime cityscape as a “live body.” Showing high-speed traffic at night from on high, with slow music, the camera pans 90 degrees left; as the enormity of the “blood cells” of the city is revealed, the music begins to pick up steam.

This passage provides a comparative perspective on light: the reflected light of the sun or the moon seems much grander than that electric light (the ancient sunlight) seen through the office windows. Yet the smaller lights and the superstructure in which they are housed completely obscure and remove from view the heavenly light. This leads to an inference about point of view. Technology is capable of magnifying our sense of wonder either about nature, or second nature and its creations. But this shot seems to suggest that the point of view established by technology (the telephoto lens; the city itself) inevitably results in a diminishing of nature, and most often the removal of nature from our line of sight and our consciousness. In fact, except for a brief cut to clouds, this is the last image of first nature that Reggio gives us for the duration of “The Grid.”

Immediately after the moon disappears the traffic returns, the music accelerating, and then a series of shots demonstrate just how structured the movement of humans is by the technological world they have created. I want now to cut to the climax of Reggio’s visual narrative, which suggests that “people are driven by machines,” in John Bramman has put it.[58]

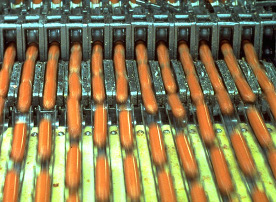

As the exhilaration increases, so does the critique’s bite – the “bejeweled beast” is a Trojan Horse, attacking the central nervous system of techno mundi. The visual narrative reiterates the motif of channeled motion: people and the objects they create move along channels which seem to follow the same logic: conveyer belts, freeways, etc. Grand Central Station looks like a high speed hive. People stream onto escalators at the PATH station below the World Trade Center. Machines produce cars, bologna and TV tubes. Cutting between people and products, we sense that people are a product of the system they have created. An overview of a Manhattan “canyon” emphasizes just how circumscribed is the human movement through the channels of this system. A dominant trope is the movement of people being intersected by traffic flows. This is shown at a speed and distance that illustrates how cars and people, flowing along the same grid, are virtually inseparable components of the same river of energy. But the visual logic of people being assembled by this system becomes ever more explicit, as when footage of hotdogs rushing out of chutes is followed by footage of people hurtling up escalators, also in multiple rows, all at the same dizzying pace.

A cumulative logic of these flows emerges: hotdogs and escalators are followed by even faster footage of car lights rushing down multi-lane freeways, then computer car races and people playing Pacman, while the pace and the music keep accelerating. When footage of a Twinkies production line is followed by images such as a stack of newspapers disappearing and being replenished, and $100 bills in a counter, and then the motherboard of a computer, the fabula comes into clearer focus. The film “does not show human beings as masters of their fate, but as creatures…victimized…by their own gigantic and overpowering productions,” Bramann writes. We are “wedged in and dragged along by developments and forces that [we] seem to design and direct, but which in truth have gone massively awry and are running dangerously out of control.”[59]

Again, for all the subtext of a “crazy life,” the beauty of this “overpowering production” becomes, if anything, even more pronounced. Car lights which had appeared like white and red blood cells moving in opposite directions through the arteries of the city now move at such an accelerated pace that the lines of light appear unbroken, a true river of energy.

The coming epiphany depends on viewers drawing inferences about the contrasts between the city seen from above (heaven’s point of view) and the sky/scrapers seen from below (the city’s view). One example is a camera in a car driving into San Francisco; when the vehicle suddenly rushes into streets hemmed in by skyscrapers, there is a sense of being trapped – a rat a maze.

After a vertigo-producing increase of velocity, a camera behind two men shows them driving a convertible through the city at a hallucinogenic speed. The sensation is like being inside a video game, but faster. The car lights become like sparks, and then there is a brief shot of a bank of TVs blowing up. As before, the explosion precedes a “cinematic Selah” moment.[60] But this time, not only the silence but the camera seems to reinforce the root meaning of Selah, to “lift up.” After moving horizontally through the nighttime techno mundi, the camera suddenly moves to a vertical view. The camera rises even higher, as if looking down on the city from an airplane or helicopter. Then from an even greater remove, there is a match cut to a satellite infrared photo of an urban ‘map’. The music fades in, an eerie approximation of

something like an interstellar transmission. Then there is another match cut to the motherboard of a computer.

“Microchip” moves between “heaven’s” view of the city, and motherboards: a vision of how the culture of techno mundi is wired. All cultures function as “a set of control mechanisms for …governance,” like a computer program, Clifford Geertz wrote. Reggio applies Geertz’s logic in a benign context – thinking occurring not in an individual mind, but via “a traffic in … significant symbols” – to the traffic of techno mundi. But Reggio leaves no doubt as to where he thinks that traffic leads. The visual narrative comes full circle by picking up that rocket’s launch skywards, where it explodes. History’s judgment of our headlong flight from nature seems terminal. The camera traces the fiery slow-motion fall of an engine, its “out of control” spin accompanied by a voice singing a Hopi prophecy about how digging up the earth “will invite disaster.”[61] The rocket engine fades into the Indian rock art, but now all the figures wear crowns – suggesting perhaps the lasting glory to be attained by returning to a balance with anima mundi.

In retrospect Koyaanisqatsi produced a “revolutionary” way of seeing the world, and has pioneered technical innovations that have profoundly influenced a following generation of audio-visual artists. Both the “new vision” and the technical innovations came out of the “stern discipline” of the film’s creators.[62] Speaking of his generation’s efforts to produce “revolutionary” narratives, Cuban film-maker Alea observed that “a greater discipline [was needed] in order to be able properly to analyze and interpret what we were living through.”[63] Reggio’s masterpiece is also evidence of a “greater discipline” through which he forged a visual narrative capable of representing epochal changes. In Reggio’s tributes to Glass and cinematographer Ron Fricke, I was struck by the emphasis that Reggio placed on each collaborator’s discipline. Discipline is “the structure that provides freedom,” it has been said.[64] Glass has said that he was surprised that the film was completed, much less watched. But out of their dedication to the emerging “new vision,” this films’ creators revised and revisioned it repeatedly, over the course of almost a decade.[65]

Reggio’s visual narrative style has been quoted in everything from car ads, to Simpsons episodes, to the Madonna “Ray of Light” video. Reggio’s ability to find beauty in the composition even of wastelands seem a clear influence on photographer Edward Burtynsky, and the adaptation of his work in Manufactured Landscapes.[66] Glass’s music composed for Reggio also has a prolific afterlife: appearing in Terry Gilliam’s post-apocalyptic film 12 Monkeys, in the TV series Scrubs, etc. In terms of its broader philosophical influence, the fabula of Koyaanisqatsi was a necessary pre-condition to a new generation of enslaved-by-our-machines cinema, such as The Matrix.

“Those who speak with words alone are not free,” Le Clézio wrote in The Giants; words must “be turned inside out,” or bypassed, to see clearly. By having “ripped out all the foreground of a traditional movie…and replaced [it] with the background that goes unseen and unquestioned,” Reggio was able to make these “well hidden big things” visible to a mass audience.[67]

Endnotes

[1] Greg Carson, director, “Essence of Life”, special feature for re-release of Godfrey Reggio, dir.,Koyaanisqatsi (MGM Home Entertainment 2002).

[2] In developing a theory of environmental film, I have drawn on David Ingram, Green Screen: Environmentalism and Hollywood Cinema (University of Exeter Press, 2000/2004); Pat Brereton, Hollywood Utopia: Ecology in Contemporary American Cinema (Bristol and Portland, OR: Intellect Books, 2005); and Sean Cubitt, Eco Media (Amsterdam & New York: Rodopi, 2005). On the deeper, international roots of the co-development of visual narrative and environmental film: Gregory Stephens, “Sisyphus in the Sand Pit: On the Iconic Character of Sand, and how the ‘anti-natural man’ Catches Water in Woman in the Dunes,” Kinema #31 (Spring 2009).

[3] Spirit of Baraka: Celebrating nonverbal films like Baraka, Koyaanisqatsi, Microcosmos and the people who made them. http://www.spiritofbaraka.com/koyaanis.aspx.

[4]On “second wave” ecocriticm, see Lawrence Buell, The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination (Blackwell, 2005), 21-28. To a degree Koyaanisqatsi shares first-wave ecocriticism’s tendency towards “celebrating nature, berating its despoilers.” William Howarth, “Some Principles of Ecocriticism,” in The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology, ed. Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm (Athens: University Georgia Press, 1996), 69. But it is more akin to “revisionist” emphasis on how “natural and built environments…are long since all mixed up,” and the articulation of a “social ecocriticism” that “takes urban and degraded landscapes just as seriously as ‘natural’ landscapes” (Buell, 22). In this sense Koyaanisqatsi set a template followed by Jennifer Baichwal’s documentary adaptation of the work of photographer Edward Burtynsky: Manufactured Landscapes (Zeitgeist, 2006).

[5] Susan Hayward, Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts, 3rd ed. (Routledge 2006), 282.

[6] Timothy Corrigan and Patricia White, The Film Experience: An Introduction (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004), 262.

[7] Mark Stokes, “The Quatsi Trilogy: Breaking the Mold of Traditional Storytelling,” Hollywood Jesus (2-17-06);http://www.hollywoodjesus.com/comments/stokes/2006/02/qatsi-trilogy.html.

[8] Kaja Silverman quoted in Al Razutis, “Menage a Trois: Contemporary Film Theory, New Narrative and the Avant-Garde,” Opsis (Spring 1984), my emphasis.

[9] Connotation “the set of associations implied by a word in addition to its literal meaning.” Meanings can be “suggested by or associated with a word or thing.” American Heritage Dictionary. Roland Barthes wrote: “the literal image is denoted and the symbolic image connoted.” “Rhetoric of the Image,” in Image Music Text, translated by Stephen Heath (New York: Hill & Wang, 1966/1977), reprinted in Carolyn Handa, ed., Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Sourcebook (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004), 152. On the connotative capacities of film visuals (vs. denotative), see James Monaco, How to Read a Film (Oxford UP, 2000), 161-63.

[10] Roland Barthes, “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives,” in Image Music Text, tran. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill & Wang, 1977). The paraphrase is Ryan’s.

[11] Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Freud’s Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable (Yale UP, 1992).

[12] Charles Johnson, “The Liberation of Perception: Charles Johnson’s Oxherding Tale,” Black American Literature Forum 25:4 (Winter, 1991), 705-28. On the “slavish adoration” of hero worship, see Gregory Stephens, “Frederick Douglass as integrative ancestor: The consequences of interracial co-creation,” in On Racial Frontiers: The New Culture of Frederick Douglass, Ralph Ellison, and Bob Marley (Cambridge UP, 1999), 85.

[13] Marie-Laure Ryan, “Narrative,” in David Herman, Manfred Jahn, and Marie-Laure Ryan, eds., Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative (New York and London: Routledge, 2008), 345.

[14] Ryan, “Narrative,” p. 347.

[15] David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: U. Wisconsin P, 1985). See also Seymour Chatman, Coming to Terms: The Rhetoric of Fiction & Film (Cornell UP, 1990).

[16] Ryan, “Narrative,” 347.

[17] “A Wordless View of Life: The Satya Interview with Godfrey Reggio,” Satya Magazine (August 2003); http://www.satyamag.com/aug03/reggio.html. Greg Carson, director, “Essence of Life,” Special Feature in Koyaanisqatsi, dir. Godfrey Reggio (MGM Home Entertainment, 2002).

[18] Claude Lalumière, “Review of The Qatsi Trilogy,” Locus Online (Jan. 1, 2003);http://www.locusmag.com/2003/Reviews/Lalumiere01_Qatsi.html.

[19] Greg Carson, “Essence of Life,” Koyaanisqatsi DVD special feature (MGM, 2002). “enormous state of humiliation,” “Worldless View of Life.”

[20] Bruno Thibault, “J.M.G. Le Clézio,” Journal of the 20th Century/ Contemporary French Studies Vol. 2, No. 2 (Fall 1998), 365-68, my emphasis.

[21] Carson, “Essence of Life.”

[22] Robert Sklar, Film: An International History of the Medium (London: Thames & Hudson, 1990), 324.

[23] Carson, “Wordless View of Life.”

[24] Michael Dempsey, “Quatsi Means Life: The Films of Godfrey Reggio,” Film Quarterly (Spring 1989), 2-11. Short description, “Essence of Life.”

[25] Patricia Aufderheide, Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford UP, 2007), 14-15. For a more detailed examination of Reggio’s relation to the city symphony tradition, see Scott MacDonald, “Godfrey Reggio,” in Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (University of California Press, 1987), pp. 378 ff.

[26] Michael Dempsey, “Quatsi Means Life.” Spiritual mission, Scott MacDonald, Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (University of California Press, 1987), 378.

[27] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken, 1969), 242.

[28] Andrew Gumbel, “Godfrey Reggio: Altered Images,” The Independent (December 13, 2002);http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/godfrey-reggio-altered-images-610804.html.

[29] Michael Dempsey, “Quatsi Means Life,” Film Quarterly (Spring 1989), 7. “Purge,” a comment made in rejecting the notion that he was a “Doomsday prophet.” Erin Torneo, “Lone Giant: Godfrey Reggio’s Naqoyqatsi,” IndieWire (Sept. 13, 2003);http://www.indiewire.com/article/interview_lone_giant_godfrey_reggios_naqoyqatsi/.

[30]This puts him in sync with a large body of post-human cinematic thought experiments. John W. Martens, The End of the World: The Apocalyptic Imagination in Film & Television (Winnipeg: J. Gordon Shillingford, 2003); Charles Mitchell, A Guide to Apocalyptic Cinema (Greenwood Press, 2001).

[31] Carson, “Wordless View of Life.”

[32] See Gregory Stephens, “Sisyphus in the Sand Pit: On the Iconic Character of Sand, and how the ‘anti-natural man’ Catches Water in Woman in the Dunes” (Kinema, 2009).

[33]The influence of the Genesis Creation story is evident in Chapters 2-4, but Mark Ezra Stokes surely exaggerates: “the order of the powerful images follow Genesis 1:1-13 to the letter.” “The Quatsi Trilogy: Breaking the Mold of Traditional Storytelling,” Hollywood Jesus (2-17-06);http://www.hollywoodjesus.com/comments/stokes/2006/02/qatsi-trilogy.html.

[34] Kenneth Burke, Language as Symbolic Action (University of California Press, 1966), p. 3. Kathryn Borman, Schooling the Symbolic Animal (Rowan & Littlefield, 2000). Terrence Wovean, The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain (Norton, 1998). Desmond Morris, The Naked Ape: A Zoologist’s Study of the Human Animal (Delta, 1999), p. 225.

[35] I’m adapting “guiding motif” (German leitmotif) from M.H. Abrams to indicate how visual narratives can employ “the frequent repetition of a…complex of images.” A Glossary of Literary Terms, 4th ed. (CBS Books/ HRW International Edition, 1981/1987), p. 111.

[36] “Koyaanisqatsi,” Review by Serdar, Genji Press (9-23-2002). “Un-nameable”: “Essence of Life.”

[37] Edward Abbey, The Monkey Wrench Gang (Perennial/HarperCollins, 2000), 64, 225.

[38]J.M.G. Le Clézio, The Mexican Dream or, The Interrupted Thought of Amerindian Civilizations, trans. by Teresa Lavender Fagan (University of Chicago Press, 1993), 161. Shepard Krech III, The Ecological Indian: Myth and History (Norton, 1999). Dziga Vertov, Man with the Movie Camera (VUFRU, 1929; Triad Productions, 2008).

[39] Luc Ferry describes contemporary humans as “the antinatural being par excellence” whose “nature is to have no nature.” The New Ecological Order (U. Chicago, 1995), xxviii, 3-5.

[40] James Monaco, How to Read a Film (Oxford UP, 2000), 161-63. “stop and meditate” is a interpretation rooted in oral tradition of the “black church.” Most commentators interpret Selahas a notation to musicians (Harper Collins Study Bible); perhaps an instruction to “pause the music, or just to stop, think and ponder, to punctuate the previous stanza.” Quote from blog entry “Transitions” from “Heavenfield” for April 12, 2008;http://hefenfelth.wordpress.com/category/psalms/.

[41] Propaganda…right causes, “Wordless View of Life.”

[42] Scott MacDonald, “Godfrey Reggio,” in Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers(University of California Press, 1987), 379.

[43] The slumdwellers’ use of water can also be interpreted as an instance of the underprivileged improvising ways to overcome hardship, one of my students observed.

[44] Alexander von Hoffman, “Why They Built the Pruitt-Igoe Project,” Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University: http://www.soc.iastate.edu/sapp/PruittIgoe.html; Pruitt-Igoe and the End of Modernity,”http://www.umsl.edu/~keelr/010/pruitt-igoe.htm. See also Walt Crowley, “Yamasaki, Minoru (1912-1986), Seattle-born architect of New York’s World Trade Center,” HistoryLink: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History (March 03, 2003); http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&File_Id=5352. Mariana Mogilevich, “Big Bad Buildings: The Vanishing Legacy of Minoru Yamasaki,” The Next American City (October 2003),http://americancity.org/magazine/article/architecture-big-bad-buildings-mogilevich/.

[45] “I will lift up my eyes to the hills, from where comes my help.” (Psalms 121: 1). “Deep within,” from the blog Reforminded by Justin Bruce, entry “Let Us Beat Our Swords into Plow Shares…the Worship Wars (February 22, 2008); http://reforminded.blogspot.com/2008/02/let-us-beat-our-swords-into-plow-shares.html.

[46] Punctuate, from the blog Heavenfield, entry titled “Transitions” (April 12, 2008);http://hefenfelth.wordpress.com/category/psalms/.

[47] Andrew Gumbel, “Godfrey Reggio: Altered Images,” The Independent (12-13-2002).

[48] “In contemporary visual culture, imagery and techniques that at first seem forever avant-garde get swiftly recycled into more commercial forms. [This is] a problem that bedevils Reggio’s style.” Michael Dempsey, “Quatsi Means Life: The Films of Godfrey Reggio,” Film Quarterly (Spring 1989), 6.

[49] Charles Tart, Altered States of Consciousness: A Book of Readings (New York: Wiley, 1969). Tart’s study grew out of psychological interest in various 1960s phenomena that inspired mass interest in this theme, and prepared an audience for Reggio: drug use, greater exposure to Eastern religions (Transcendental Meditation, etc.), and wilderness experiences (back to the garden, etc.). But academic interest in the notion of “expanded consciousness” is much older: see William James’ classic, The varieties of religious experience (1902).

[50] David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (U. Wisconsin Press, 1985), 49-50. For example, the coming of age/rites of passage narrative of Walkabout infers a fabula about how Western techno mundi has walled itself off from nature, including its own sexuality. Gregory Stephens, “Confining Nature: Rites of Passage, the Ecological Indigene and the Uses of Meat in Walkabout,” Senses of Cinema #51 (Summer 2009);http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/09/51/walkabout.html.

[51] Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film, 49-50. Allison Arnold Helminski, “Memories of a Revolutionary Cinema,” Senses of Cinema (1999); http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/2/memories.html; David Balcolm, “Short Cuts, Narrative Film and Hypertext” (1996),http://www.mindspring.com/~dbalcom/short_cuts.html.

[52] David Lodge, “Analysis and Interpretation of the Realistic Text,” in Philip Rice and Patricia Waugh, eds., Modern Literary Theory: A Reader, 3rd ed. (London: Arnold, 1996). The specific wording is taken from an on-line analysis of Lodge, titled “Fabula and Syuzhet,”http://everything2.com/e2node/Fabula%2520and%2520Syuzhet.

[53] Michael Crorty, “Constructionism: The Making of Meaning,” in The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process (Sage, 1998), 42-65. A template in the field: Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983/1991). Recent applications to the realm of identity politics: Joan Ferrante and Prince Brown, Social Construction of Race and Ethnicity in the U.S., 2nd ed. (Prentice Hall, 2000); Tracy Ore, The Social Construction of Difference and Inequality: Race, Class, Gender and Sexuality, 4th ed. (McGraw-Hill, 2008).

[54] Reiteration: David Lodge, “Analysis and Interpretation of the Realist Text,” in Philip

[55] Alexander J. Marshall III, “Faulkner’s Metaphysics of Absence,” in Faulkner and Religion, ed. Doreen Fowler and Ann J. Abadie (University Press of Mississippi, 1991), 180. Arthur Symons, The Symbolist Movement in Literature (Haskell House, 1971), 196; Alexander Marshall, “William Faulkner: The Symbolist Connection,”American Literature, 59 (1987), 389-401. “Shadow…branch” quoted in Nicolas Tredell, “The Sound and the Fury” and “As I Lay Dying”: Essay, Articles, Reviews (Columbia UP, 2000), 86. Re: the “humiliation” of language, Faulkner said his goal was to “try to express clumsily in words what the pure music would have done better.” James Meriwether and Michael Millgate, eds., Lion in the Garden: Interviews with William Faulkner, 1926-1962 (U. Nebraska Press, 1980), 248.

[56] Palimpsest narration: “a document…written upon several times, but each inscription bears witness to one identifiable hand.” David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film, 325, 332.

[57] Thom Hartmann, The Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight: The Fate of the World and What We Can Do Before It’s Too Late (Three Rivers Press, 2004).

[58] John Bramman, “Koyaanisqatsi,” in Educating Rita and Other Philosophical Movies (Cumberland, MD: Nightsun Books, 2009); http://faculty.frostburg.edu/phil/forum/Koyaanisqatsi.htm.

[59] Ibid.

[60] The etymology of Selah is uncertain, but its “meaning seems to be connected with rising or lifting.” “Revised Common Lectionary Commentary” (Feb. 10, 2008). The idea that this may be a direction to either players to “lift up” reminds me of Jamaican singers exhorting the band to “pull up” the music when they want highlight some words. This form of “dub philosophy” is similar to Reggio’s intent in this instance of “lifting up.”

[61] Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (Basic Books, 1973), 44-45). “Significant symbols” is adapted from G.H. Mead. Many viewers think that they are seeing the Challenger disaster, but this occurred three years after Koyaanisqatsi’s release. This is actually footage of an unmanned Atlas rocket (the Mercury program) circa 1961.

[62] Ralph Ellison, “A Very Stern Discipline,” Collected Essays (Modern Library, 1995).

[63] Alea, Allison Arnold Helminski, “Memories of a Revolutionary Cinema,” Senses of Cinema (1999).

[64] Gail Straub, The Rhythm of Compassion: Caring for Self, Connecting With Society (Journey Editions, 2000);http://www.soulfulliving.com/conscious_service.htm.

[65] Glass’ surprise, Alicia Zuckerman, “Philip Glass and Godfrey Reggio: The Koyaanisqatsi duo on their trippy trilogy and their new comedy, New York Magazine (5-29-2005).

[66] Manufactured Landscapes, directed by Jennifer Baichwal (Zeitgeist Films, 2007).

[67] J.M.G. Le Clézio, The Giants, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (London: Vintage, 1973/2008), 12-15. “well-hidden,” Le Clézio, The Giants, p. 12. “Foreground”: Erin Torneo, “Lone Giant,” IndieWire (September 13, 2002), and “Essence of Life.”

Created on: Tuesday, 7 September 2010