This article was originally published in Australian Journal of Screen Theory nos. 5-6, 1979; and reprinted in An Australian Film Reader, edited by Albert Moran and Tom O’Regan, Currency Press, 1985. It is reprinted here with the author’s permission.

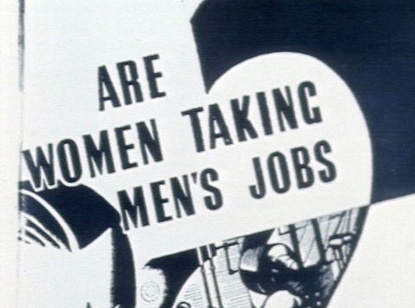

In recent years there has been a burgeoning of independent women’s films made in Australia – usually short, inexpensively produced, often made collectively and frequently on 16mm or video. The ‘Womenvision’ event in March 1974 marked an historic occasion and led to the first women’s film workshop and the formation of the Sydney Women’s Film Group. In 1975, International Women’s Year (IWY), the Australian International Women’s Film Festival was organized and the idea of the Women’s Film Fund was put forward. This was established in Federal Parliament in December 1976, the finance coming from monies allocated for a film project during IWY (a grant awarded to Germaine Greer and subsequently withdrawn) and from returns on an IWY investment in Caddie. The Fund is administered by the Office of Women’s Affairs and its financial management is vested in the Australian Film Commission. In 1976 a report, ‘Women in the Media’, was produced by the Australian Film and Television School and subsequently the School’s Open Program has been running training courses specifically for women. In 1977 the exhibition of Australian women’s films, ‘Womenwaves’, was assembled by Sydney Women’s Film group, screened for a month at Sydney Filmmakers Co-op and then toured interstate. In 1982, For Love or Money was released, a feature-length documentary history of women and work in Australia.

This is a fairly random account, isolating certain key events, to give an indication of the development of a women’s cinema in Australia in the 70s. This growth is simultaneous with the Australian feature film renaissance, and although the connections on the economic level are complicated, there is a clear demarcation between the glorious rebirth of an independent and specifically proclaimed Australian cinema and the irruption of a cinema which marks its ‘independence’ not as national but as sexual. The growth in production of women’s films has occurred because of the political activities of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Organisations such as the Sydney Women’s Film Group (along with Women Media Workers and the Australian Women’s Broadcasting Co-operative) operate not simply as creators (film-makers and media professionals) but as pressure groups whose practice is informed by political concerns generated by a cultural movement, a movement concerned to disentangle the female condition from an ideological conception of ‘mankind’ and to contest the oppression of women in specific socio-economic situations.

In this context feminist film production[1] involves a double movement: a struggle to gain access for women to the means of production (which involves the ‘positive discrimination’ exercised by women’s training courses, and lobbying for government funding), and a struggle on the level of meaning-production, of image formation. A general feminist critique of the way in which images of women are constructed in culture extends to a cinematic process of transformation, the production of alternative images, of a point of view radically different to that offered by the dominant patriarchal perspective.

These two aspects of feminist film production cannot be separated; they are part of a process and in so far as they constitute a movement for change they are inevitably linked to questions of distribution and exhibition, to questions relating to audiences: who are the films made for, where are they screened, how are they talked about, thought about, conceptualized. In some respects the political basis of feminist films gives a particularity to these questions – they are made (in the words of the Women’s Film Fund guide) for, by or about women. Yet while such a description specifies women as subject and object of the cinematic process, it is extremely generalized in its conception of ‘women’ and indicates change only in terms of a shift in emphasis.

It is unsatisfactory to assume a homogeneity to either the term ‘feminist’ or ‘independent’, but for the purposes of this paper I want to isolate questions to specificity (to do with women’s films) and broader questions to do with change (with cinematic transformation). I hope to open out questions of dislocation in the area between control over the means of production and the activities of producing and subverting meaning. For it seems to me that this is of crucial concern to questions of political change and involves debates within the women’s movement and within film culture in Australia.

By film culture I mean not simply Australian films but the cultural context in which all films are screened, promoted, discussed, reviewed, theorized. This film culture (even if it is amorphous and unselfconscious) has assigned particular places and meanings to both independent and women’s films. ‘Independent’ is a term which covers a multitude of signs: from chauvinistic declarations of a home-grown feature film industry to the avant-garde to agit-prop. These signs function as labels indicating the content of packages. As such the signs are frozen and those films which refuse a fixity of meaning, which utilize language as a play of differences, which foreground the production of signs and meanings are censored. They are censored in the Freudian rather than the judicial sense for there is no official ban as such; rather it is cultural (and can find expression in a marginal journal like Cantrill’s Filmnotes). But more significantly, what is censored is that which exists in a potential rather than in a material form; censorship operates as a prohibition on utterance.

There are constraints upon what kinds of films are made and how films are discussed. In the context of this kind of censorship the political questions of feminist film production are often flattened out and posed in terms of messages and effects (in both film culture and feminist circles). In looking at some contemporary films I want to open out that which is censored both to indicate that films are not fixed representations, that they may embody contradictory tendencies and modes of pleasure, and also to suggest, through this analysis, possibilities of alternative cinematic practice.

The area of independent film production is riddled with contradictions. Generally ‘independent’ is taken to mean not dependent on big business and large private capital. It marks an attempt to work outside the ownership and control of film and television companies under capitalism. But independent films are generally dependent on small private capital and on state funding bodies. The term ‘independent’ can also connote freedom from authority, autonomy, freedom of expression. But the very existence of state experimental and cultural funding bodies ensures a legitimized and prescribed space to those films which are marginal, original, creative, oppositional. The films are supported by audiences that occupy that space – at art galleries, film co-ops, campuses, political meetings, film conferences. Non-theatrical exhibition delineates a practice outside that of the mainstream industry. But there is still a network of production, distribution and exchange, and in the area of independence this can often lead to a problem of circularity – the same small films keep appearing before the same small audiences at the same small places.

Often this is not seen as a problem; for independent creativity popularity can signal the kiss of death. But if there is a belief that control over the means of production (film production) secures the conditions for freedom from the restraints imposed by the profit orientation and the dominant ideology, then questions of audience and popularity became crucial and also problematic. For it becomes a question of ideological practice, of changing people’s minds, of producing new and different meanings, of ‘winning’ audiences. It becomes a struggle to contest and to capture. That which escapes the hegemony of the dominant ideology cannot, by definition, be popular; but film production can be concerned with the production of a ‘popular’ audience – popular in the Brechtian sense of a non-elitist audience engaged with culture in a work of pleasurable production, a process of historical transformation.[2] In this context independent film-making is crucially concerned with contending and opening up the established relations of distribution and exhibition, with challenging the institutional space that defines the relationship between films and audiences. Processes of production cannot be separated from processes of distribution and exhibition for it is not simply a case of finding a place to show films but of creating a specific space in which films can produce audiences engaged in productive activity.

I emphasise the links between production, distribution and exhibition because the political effectivity of cinematic practice needs to be grounded in an analysis of the material conditions which situate a range of relations of exchange within the social formation. The contradictions of independence/dependence and popularity/popular render problematic the ideological dimension of feminist cinematic practice.

The situation in Australia is complicated because the administration of funding bodies varies from state to state. As Sandra Alexander points out, both Film Australia and the South Australian Film Corporation have shown some sympathy to women’s demands. Yet funding is not unconditional as is vividly demonstrated in the case of Seeing Red and Feeling Blue where, in the editing stages the film was considerably altered by Film Australia without the knowledge or consent of Jane Oehr, the director.

A more explosive and public case centred on the struggle for the rights to distribution and exhibition of the film Me and Daphne, made by people at the Film and Television School. It is set in a chicken factory and concerns the working conditions of women. The Film School, claiming that the film was not up to professional standards, objected to its distribution and took out an injunction against screening of the film. Ironically, at the same time the Open Program was running training courses for women in the media. People involved in the production of Me and Daphne have continued the struggle to have the film screened and discussed in various social situations.

Clearly, what is at issue here is not just a controversy over independence/dependence; what is also at stake is the status of professional film language (the conventions of coherence, continuity, transparency and distinctions between the categories of narrative and documentary) and the threat to its dominance by cinematic strategies which challenge the ideological underpinnings of ‘competence’.

The case of Me and Daphne draws attention to film as a process of production involving the relationship between film and audience. The two aspects of production mentioned earlier (access to and control over the means of production, and the production of meaning, image formation) are seen here to be clearly related but in a problematic way. Films are not simply moulds which can be filled with meaning and then put on the market as commodities. Meaning is not something that resides in the world or in people’s heads and can be directly transferred in an unmediated state onto celluloid. Film has a material substance – sounds and images on celluloid. To talk of film as a language, as a process of structuring meaning, allows us to confront the notion of film as a mirror reflecting the world (or distorting it) and to examine the ideological operations of the cinema. It also demonstrates that control over the means of production does not automatically guarantee subversion of the dominant ideology; it is little use changing the relations of exchange (involved in production, distribution and exchange) without changing the language. It is necessary to challenge the relationship between film and audience based on a communications model of a message passed from a sender to a receiver, and to work on a more dynamic relationship where the film is seen as a text, as producing meanings, thus engaging the viewer as a reader participating in the production of meaning.

This perspective is vital to the development of any feminist cinema concerned with change, with ideological practice. Most of the reviews of ‘Womenwaves’ celebrate the events as a rare opportunity for women to identify with recognizable images, but there is little discussion of film language except in terms of style, content and technical competence.[3] A space is opened up for women to experience real pleasure in an event such as ‘Womenwaves’ where the ideal spectator is not, as is usually the case, posited as male. In varying ways and to varying degrees these films contest the relationship of identification which films set in motion between themselves and the audience. But there are difficulties here which have to do with notions of identification and representation – in replacing the ideal male spectator with an ideal female spectator there is the danger that the term ‘ideal’ remains intact and the representational process remains one of idealization. By this I do not mean to refer to a technique of glossy perfection, but rather to an informing conception of an archetypal model of woman, an imaginary plenitude. The impulse to create and talk about realistic portrayals of women, to evaluate films according to a scale of values measuring the degree to which they do or do not reflect the real experience of women is to posit an essentialist notion of woman. It is to assume that there is something essentially female, a female voice, which has been suppressed, but given the opportunity for self expression will reveal itself as fully constituted, as an integrity. The appropriate cinematic mode for this kind of discourse is realism.

Most of the films with which we are familiar adopt a mode of realism; whether disaster movies or Westerns or weepies they articulate images as though the process is a transparent representation of reality; the marks of cinematic production are effaced or contained so that meaning appears to unfold naturally. The viewer is thus fixed in a certain relationship to meaning, a fixed unquestioning relationship, but is posited as neutral, as precisely without a position. The viewer of Hollywood cinema is allowed to imagine himself/herself as invisible: “the scene ignores that it is seen..and that ignorance allows the viewer to ignore himself/herself as voyeur.”[4] But it is this very process which assures the viewer a secure place as subject of experience, as a unified viewing subject, as subject of the film and origin of meaning. Of course there are possibilities for decentring the viewing subject, for most film texts are crossed by a number of different discourses. However, in the classic mode various strategies, but in particular the language of narrative, work to homogenize the diverse discourses, to contain them within a dominant meaning and to reinforce the identification processes.

Realism, and its combination with narrative structures, is ideological in that it assumes and purports to reproduce a version of reality which is seen as natural and true. But reality is not something given to consciousness in a natural and pure form, rather it is organized, structured in a social formation and in an historical context. Ideology is produced by material conditions and has material effects, but it is essentially unconscious in its operations. When relationships of exchange in the market place are experienced as relationships of equality freely entered into by equal individuals it is not that these relationships are not real, in fact they are experienced as very real, but rather that a relationship which consists of both production and exchange is represented as though it were only an exchange relationship. In other words the structural relationship of production whereby surplus value is appropriated by one partner of the exchange through exploitation of wage labour is obscured.[5] The structural relationships and processes of production are effaced and an ideology embracing both ‘mankind’ and ‘individuality’ is promoted and maintained. Cinematic modes which efface the material conditions of production, which appear to present a given and transparent reality employ the language of the dominant ideology.

This has immense implications for the representation of images of women. For it cannot be assumed that there is a true reality which can be captured. The images of women that we know are socially and culturally constructed in a variety of languages and through a variety of social practices and relationships. Any activity of subverting commonsense notions of reality requires a dismantling of the homogenized discourse of patriarchal linguistic structures. Many of the films currently being made by women in Australia are concerned with such an activity. Films such as Selling of the Female Image, Image Plus, Gravelle, Changing are concerned with a critique of images of women as constructed by the media, whilst others such as Ladies’ Rooms are concerned with exploring the interior and exterior world of a female culture suppressed by patriarchy.

Of the former type many are concerned with ‘roles’ that women are forced to play and depend upon techniques of role reversal and an exploration of true expression, a representation of the ‘true’ woman counterposed against ‘false’ images. But others are more experimental in their use of film language and their analysis of sexism. Of these the most interesting and potentially most subversive is Image Plus and Mary Callaghan’s earlier film, Notes…Women as Media. These films draw attention not only to the fact that images of women are culturally constructed, but also draw attention to the fact the film itself is a text, a production of meanings, utilizing a range of languages, which are not fixed but can be reconstructed. On the image level there is a juxtaposition (through editing, and within the frame, frequently foregrounding the camera’s focusing mechanism) of advertisements, fragments of television soap opera, magazine models, written texts (inscribed on celluloid) and images of women working within the home. The sound track intermingles, and often overlays, narration, quotation, the sound of radio and television, the lyrics of popular songs. The earlier film announces itself as ‘Notes..’, a reference to the written word (often considered alien to the cinema’s essential vocation in capturing concrete reality) but also to signs as an element of language, to the production of meaning as a play of differences, open-ended, rather than foreclosed by any one meaning. Notes…also plays on the image of a woman in front of a mirror making up her face. At one stage she stares directly at the camera, at us as audience, as inverted mirror, and paints her cheeks with war paint. The film ends with grease paint smeared over the mirror, a blurred image, rendering problematic the image of woman as ‘made up’, and the notion of film as a mirror on the world. In this case the scene does not ignore that it is seen and does not allow the viewer to imagine herself as invisible. Neither does it allow easy identification with a recognizably authentic character. It is thus a difficult film to talk about (because it does not allow us to secure a position as viewing subjects) but it does open up possibilities of discussing the way in which our culture, and specifically cinematic language, constructs and reconstructs images of women.

Ladies’ Rooms, more concerned with describing the positive, personal and suppressed area of a specifically feminine culture, describes itself as a “documentary that ends on a note of fantasy”. We are given four women in their rooms talking about themselves and their personal space. We are then shown them, individually, in an expanse of green grass, assembling the objects of their rooms around them. It is easy to identify with the characters and each one presents us with a personal, narrative account of their individuality and consciousness. But underpinning the individual accounts is a notion of ‘women’s space’, a generalized, amorphous area which stresses women’s culture as the personal, the privatized. The attempt to open up this space by the fantasized finale seems to me to actually enclose the film, close it back on itself and in the process it enmeshes, rather than decentring the viewer in its discourse. It is an appeal for self-expression rather than change, and this is evidenced in the orthodox coherence of the film language.

But while the political effectivity of films like Ladies’ Rooms may be limited by an essentialist and individualist ideology, they nevertheless provoke serious questions to do with the specificity of the female condition and the possibilities of film language for offering both an analysis of this condition and for promoting new modes of pleasure (to do both with eroticism and knowledge) that are not circumscribed by masculine definitions.

The cinema, as a signifying system, is situated within the realm of symbolization, the production of meaning and the pursuit of pleasure. Films construct subjects – both subjects of narration and viewing subjects positioned in relations of identity and difference to the screen. An interesting article by Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, argues that the pleasure of narrative is dependent on identification processes that ensure the objectification of women, and that the element of voyeurism involved in film viewing is linked to masculine sadism. There are also implications in this work about masochism and narcissism which sound a warning note to feminist cinema of the dangers of being caught on the wrong side (the other side, but the same coin) of patriarchal language.

Before discussing Seeing Red and Feeling Blue and We Aim to Please I would like to mention Maidens, which I have only seen once but would like to see again for it is an extraordinary mixture of feminist and cinematic riddles. It is a film which hovers precariously between rapturous narcissism and analytic objectification, between the ordered documentation of the family tree and the silent anguish of the family drama, between the narrative of desire and the joy of the joke. It is continuously interrupted by fragments of other films, including earlier work of the Sydney Women’s Film Group and Secret Storm, so that while it is a very personal odyssey it is also a discourse on independent feminist film practice in Australia.

Seeing Red and Feeling Blue is a film about seeing and feeling rather than about colours. It is a film that attempts to capture the real feelings of colour rather than to use colour as an element of film language in the development of discourse on the contradictions of red/blue, seeing/feeling. In Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her, a character, addressing the camera, asks herself what would happen if everyone suddenly decided to call green, blue; the arbitrary nature of signification is addressed in the film through the dialectic of sound and images, but so is the cultural construction explored and the constraints of language; the same character muses that “language is the house man lives in.” In Seeing Red and Feeling Blue language is the house woman lives in. The film language is more constrained, more homogeneous than in Two or Three Things but this is because the film is about that which is not spoken of, it is about menstruation in that it circles around the object of representation – the relationship of woman to her own body – never quite touching for it is a relationship which cannot be represented by patriarchal language.

Members of the Women’s Theatre Group appear in the film, both as themselves discussing amongst themselves the subject of menstruation, and as actors performing review sketches on the way in which the topic has been traditionally handled – by mothers, in biology classes, by Freud. These sketches are inserted into the discussion group sequences as are songs over lyrical montage of women – women everywhere, happy women, sad women, expressionless women. The film is structured in such a way as to allow for a number of discourses but in fact it is dominated by the discourse of experience, of consciousness. The Women’s Theatre Group are introduced individually and in the discussion function very much as ‘talking heads’; it is a classic consciousness raising session, an expression of feeling. And like any consciousness raising group it is fraught with contradictions for it is not simply a matter of levels of consciousness but of the effects of the unconscious in speech, in exchange.

The film does not articulate the unconscious as related to ideology and therefore it does not give any indication of political activity except in terms of emotional support. But it does provide a kind of pleasure. It may be the pleasure of recognition, but for women it is recognition of that which has been suppressed, unspoken: it is “the putting in place of new representations”. This production is achieved not in the discussion sequences (nor in the humorous sketches) but in their interaction with the framing sequences.

The film opens with a voice narrating myths about menstruation as a painted moon rises and fills out. The narration continues as the image cuts to depict a group of women wrapping in cellophane and encasing in plaster of paris a naked woman surrounded by redness. The titles come up over the mask-like face. The film ends with lunar rituals, a celebratory removal of the plaster cast, and the image of a small girl dressed in vivid red. There are strange elements of mysticism here but the ritualisation gives a symbolic weight to the plaster cast – the house, the language, the culture that imprisons woman’s body.

We Aim to Please is described in the ‘Womenwaves’ program as a “personal study of female sexuality, missed feelings of fear, doubt and paranoia, with joy, humour and eroticism”. It is indeed a cacophony of sounds and images and very personal in that the film-makers Robyn Laurie and Margot Nash, literally lay themselves bare before the audience. But they are not the subject of the film and the viewer cannot through identification find a fixed and secure position as subject. If the film is concerned with female sexuality it is certainly not a conventional documentary. It offers no unified perspective and in this sense ‘defies description’; hence the plethora of abstract nouns (of states of being) used to describe the film. But the film language actually draws attention to its materiality and to processes of producing meaning and provides space for us, as viewers, to participate in that production – to read the film as a text.

The title We Aim to Please is double-edged: as an articulation of the traditional female function its irony signals a subversion, a rupturing of passivity; but in another sense the film does aim to please, to generate pleasure through an understanding of female sexuality. The play of words in the title promotes the dimension of ‘wit’ that Michele Montrelay isolates as an aspect of feminine pleasure.[6] But the title cannot be seen apart from the film text, it is inscribed into it, literally ‘written in’, and can only be understood as ‘putting the dimension of repression into play on the level of the text itself.

Sound is heard before images are seen: ‘how alone we feel, how defenceless’. A series of disjointed images follows: faces, a bronze figurine, a doll, carved out representations of a constructed femininity. ‘But we’re finding out fast’, the ‘characters’ tell us and repeat the phrase. We are shown them ‘making up’ their faces as the phone rings incessantly, an elaborate and stylized ritual which suggests both the made up face which aims to please and also war paint. In extreme close-up grotesquely painted red lips speak slowly of the construction of female images for male consumption, for man as the ideal spectator. A written insert reads THAT’S YOU and cuts to Robyn Laurie pointing aggressively as us, the audience. The women write up the title, hurl a tomato at the camera, followed by an image in which the smashed tomato oozes and fills the screen.

This assault on the audience has a distancing effect endorsed by the juxtaposition of images in a non-sequential offer and the insertion of written words, the mouthing, the ‘acting out’ of quotations. It makes us very aware that we are watching a film but also uncomfortable for it alerts us to the cinematic conventions which place us as women in a male-defined position, to see (ourselves) from a male perspective. This is disturbing; it de-centres; it alienates us – but it is alienation in the Brechtian sense and demands that we question the notion of audience as passive consumers and women as passive constructions.

Later in the film the camera ‘holds’ relentlessly on Robyn’s race crossed by shadows as whistles pierce the sound track. This articulates with a later image of a watermelon smashed open, battered by a hand using a beer bottle as weapon. The dialectical production of meaning here recalls a slogan used by the women’s movement – rape: the end of every wolf whistle. Working in opposition to these meanings are images of the two women naked and relaxed talking of their cunts, their relationship to their own bodies. The film is intercut with close ups of naked flesh, hands caressing the body, the camera moving slowly over caressing the body.

The film ends with a red rose opening and filling the screen; ‘the end’ painted on naked arses; the image of a leaping tiger. The splattered red tomato has been negated by a revolutionary red rose opening out. The painted faces, the aloneness and despair, has been overlaid by naked women laughing, clenched fists raised. The film thus ‘opens out’, but it also encapsulates issues which seem to me to work against its productivity. The extremely lyrical presentation of naked bodies in green foliage caught in slow camera movements and soft focus force a problematic connection between women and nature. Thus the warning not to ‘mistake a stage of capitalist development for a state of permanent torture’ is given little substance. There is no exploration of the connections between women’s oppression and capitalism and change for the better is implicitly posed as a return to nature.

There are films such as Don’t Be Too Polite Girls and A Film for Discussion which are more revolutionary in their analysis of the socio-economic condition of women, and it is vital for change that feminist film production continue this line of development. I have chosen to look at films more specifically about the sexuality of women in order to raise issues about the production of meaning; to explore the links between pleasure knowledge and change.

Endnotes

[1] Having situated this area of production in a political context I use the term ‘feminist’ but do not mean to imply that all films made by or about women are directly political.

[2] See “Notes on the Idea of an Independent Cinema” by Claire Johnston. The paper is available from the British Film Institute as is ‘Independent Film-making in the Seventies’, a paper from the organizing committee for the Independent Film-makers Association conference held in May 1976.

[3] For coverage of ‘Womenwaves’ see, in addition to Sandra Alexander’s article (“Womenwaves”. Directions in Film and Video. Hecate February 1978) Cinema Papers, April-June 1978 (Barbara Alysen), Filmnews, January 1978 (Joan Weinberg) and February (Marsha Bennett).

[4] Christian Metz quoted by Paul Willemen in “Voyeurism, the Look and Dwoskin” in Afterimage No. 6, Summer 1976, a special issue on “Perspectives on English Independent Cinema.”

[5] See Stuart Hall, “Culture, the Media and the Ideological Effect” in Mass Communication and Society, Curran, Gurevitch and Woollacott (eds.), The Open University, 1977.

[6] For an introduction to her work in translation see Montrelay: “Inquiry Into Femininity” in M/F no. 1, 1978.

Created on: Sunday, 5 September 2010