The following essay is a revised version of a talk on the cinematic influences in Bill Henson’s photography presented as part of the Sydney Festival on the occasion of Henson’s survey exhibition “Bill Henson” at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 8 January – 3 April 2005, Sydney. It is published here with the kind permission of the author.

“Photography never ceases to instruct me when making films. And cinema reminds me at every instant that it films motion for nothing, since every image becomes a memory, and all memories congeal and set.”

– Agnès Varda, 1984

In his first solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Melbourne in 1975, Bill Henson arrived on the Australian art scene much like a fully-formed, twenty year old, Orson Welles-like figure, a creative genius exhibiting an art of dark beauty, decadence and melancholy. Henson’s photography from the mid-to-late 1970s, both in black-and-white and colour, display many of the aesthetic and subjective elements that would resurface in various important expanded formal arrangements and contexts throughout his later oeuvre. I am reminded of what François Truffaut had once said of certain seminal filmmakers: “All of Orson Welles is in the first reel of Citizen Kane, Buñuel in Un Chien Andalou, Godard in Une Jeune Coquette; and all of Jean Vigo is in A propos de Nice.” [1]

And speaking of Vigo, his cinema of earthly desire and poetic realism is strongly echoed in Henson, particularly by way of an emphatic representation of naked and vulnerable adolescent subjects existing in a night world of drugs and eroticism. Henson’s subjects, like Vigo’s, but unlike Larry Clark’s or Nan Goldin’s, become eerily synonymous with the baroque architecture of their surroundings and the nocturnal-infernal landscapes they inhabit. Contrary to the more glib response of disdain to Henson’s erotic suggestiveness and, in general, his characteristic painterly depiction of the body, there is, as Peter Craven correctly states, a sustained and resonant critique of the slick pictorial conventions of the Vogue-style photography that is endemic in our mass media.[2] In this sense, André Bazin’s claim that Jean Vigo had an “almost obscene taste for the flesh” could also cautiously and appositely apply to Henson.[3]

Henson’s photographic practice contains dark expressive content that is singularly beautiful at the same time as it is acutely disturbing. By the mid-1980s, with its nonpareil use of light and dark, subject and location, colour and monochrome, his photography was impressively very mature. The Untitled 1983/84 series include photographs that speak of oppositions, ambiguities, parallels and repetitions to signal the complex and dynamic processes of the human imagination. The images of baroque palaces, paintings by old European masters in galleries, and naked junkie children lost in their suffering, when exhibited in the familiar diptych and triptych forms and from floor to ceiling, not only have a powerful emotional impact, they dramatically challenge the viewer’s imagination. The colours of most of the images have been drained, creating a cold and vulnerable effect; interiors glisten in half-light and the exteriors are dusky in their appearance; typically, the faces and figures of Henson’s subjects emerge from the darkness looking demonic or melancholic.

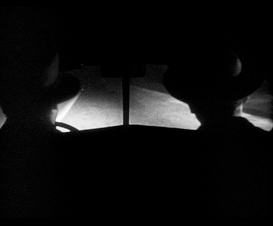

But what matters most as we look at each photograph is not the individual image as such, but the tensions, nuances and ellipses between each photograph and in their overall sequencing. This is fundamental to any understanding of Henson’s art: his series of photographs should be read as a single sustained “image” with its own internal harmonies, rhythms and continuities. In fact, it is a key aesthetic characteristic of Henson’s work and is precisely reflected in the way that Henson has chosen to present the survey show. As you enter the first of the ten rooms that comprise this exhibition, you are immediately conscious of how dark the room is and that the photographs are purposely dimly lit. One is forced to view them in a speculative, forensic manner for we have entered a twilight world of light and darkness where ambiguity of meaning, feeling and thought are inextricably intertwined, a shadow world where what is not so visibly clear has, in Henson’s words, “the greatest potential to transmit information.”[4] In this context, from the moment we see the first photographs, we are made mindful of how their aesthetic elegance and dramatic subject matter are arguably connected to German Expressionist cinema of the 1920s, American film noir (including its more recent offshoot of the neo-noir film), and to particular strains of European art and avant-garde cinema.

But while the portentous symbology and distinctive chiaroscuro stylistics suggest these particular cinematic influences, it should be stressed that familiarity with classical art and European literary modernism have also unmistakably shaped the thematic and formal preoccupations of his photographic practice. It is apt to quote Raymond Chandler’s famous words in this instance, “The streets were dark with something more than night.”[5] The cinematic, the literary and the painterly in Henson’s work reverberate with each other in significant and telling ways.

In the last two rooms of the survey show we encounter desolate, broken-down urban environments located at the edge of the city, where seedy-looking, vulnerable teenage figures wander about lost in a twilight world, and where skies are illuminated by artificial and natural effects. Henson’s mysterious landscapes and skies suggest the influence of the paintings of the German Romantics and substantially indicate a preoccupation with the transcendentalism of beauty and nature and light and dark. In these particular photographs from the mid-1990s to 2002/03, Henson is concerned (without resorting to nostalgia) with the more recent ideas of the sublime and the self’s dissolution within nature. Judy Annear has rightly observed that Henson’s depiction of clouds and night skies has a possible relation to Alfred Stieglitz’s early 1920s black-and-white cloud images.[6]

But the strange beauty of Henson’s images of the sky, taken during the day and night, also convey a sense of agitation that – as the elusive French filmmaker Chris Marker reminds us in his documentary about Andrei Tarkovsky[7] – is related to one of the favourite camera angles of classical cinema, one in which a figure in the frame moves across it against a tilted angle of the sky. Henson’s night scenes in this series and elsewhere suggest the possible influence of this particular feature of classical cinema.

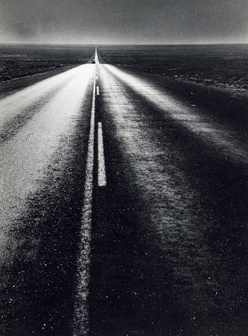

Another talismanic image for Henson is that of a deserted nocturnal road leading to a distant horizon. This photograph’s subtle play of light and dark immediately denotes the pervasive presence of chiaroscuro lighting (or what is sometimes termed “Rembrandt lighting”) conferring to it the familiar visual atmospherics and emotional colours of German Expressionist cinema and film noir. Both of these film categories are aesthetically and historically linked, and are hugely indebted to the expressive use of light and shadow in European classical painting and nineteenth century photography. Moreover, Henson’s night road also emphatically connotes a seminal photograph of the road in American art and culture, Robert Frank’s vertically framed, night-lit U.S. 285, New Mexico from his book The Americans.[8]

Alfred Appel Jr., in the book Nabokov’s Dark Cinema, notes that Frank’s decision to shoot the road at night (as opposed to during the day) was a transformative one in that he delineated his highway into a potent symbolic expression of a psychological state.[9] In Appel’s words, Frank’s photograph recorded “the erosion of the fabled open American road” epitomised by Archibald MacLeish’s utopian utterance in the 1930s that “America was promises.”[10] A desolate stretch of road at night is an iconic image of film noir – just think of the opening images of Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946) or Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

Similarly, what Henson’s photographs have in common with American film noir of the 1940s and ’50s is an atmosphere or mood of ambiguity, existential fragility and menace, belonging to a universe where dreams and consciousness blur, displaced characters are living in the margins of society, at the end of the road, in a world of decay, and where things are not what they appear to be.

But film noir is more than the mood, tone and style inherited from German Expressionist films of the 1920s, American hard-boiled crime fiction , or French poetic realist cinema. The great Danish director Carl T. Dreyer once said, “Nothing in the world can be compared to a human face. It is a land that one never tires of exploring, a landscape (whether rugged or peaceful) with a unique beauty.”[11] Dreyer’s face-landscape metaphor suggests that by exploring the face as a place with an otherness, the cinema is able to “produce a world of epiphanies, of things endowed with a look,” to borrow words from Jean-François Chevrier’s and Catherine David’s Passages de l’image.[12]

The human face as a window to the human soul is something very evident in European art cinema, particularly in the films of lngmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, François Truffaut, as well as Dreyer, to name only a few. But it is important also in film noir – certainly in films by Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, Jacques Tourneur and Orson Welles – where the so-called chiaroscuro “choker” close-up of the human face is key to the form’s iconography. From his earliest photographs, Henson has been involved with photographing the human face in close-up and with low-key lighting, allowing him to suggest or inject nuances of fragility, horror, sadness and pathos into his art.

The Paris Opera Project of 1991, which was actually staged in Henson’s studio, was a commissioned series meant to signify the effect of listening to music. It is an archetypal series in that Henson has produced a drama of painterly human portraiture by framing human faces in various stages of response (indifference, apprehension, surprise) to music. This Rembrandtian shaded fresco of human faces and gestures in rich brown, gold and dark green, represents a lyrical meditation on the face intent on looking away (to off-camera space á la Dreyer) to something “other”. In certain photographs Henson has “scratched” and thus distorted the human face in ways reminiscent of American avant-garde filmmakers Kenneth Anger and Stan Brakhage, both of whom created similar textual features to the faces of their subjects in their “trance” films of the 1950s. While in numerous other photographs, Henson has presented the human body as a Murnau-like “vampiric” object in extremis: the body has become fragmented, distorted, abstracted, bathed in the definitive chiaroscuro stimmung of German Expressionist cinema.

According to the German film historian, Lotte Eisner, stimmung was meant to suggest “the vibrations of the soul” by connecting it to the use of light[13] and, to be precise, was something that applied to everyday objects as well as to human figures.[14] It was often rendered through “veiled” landscapes, interiors with low hanging lamps, chandeliers, or even a penumbra produced by light beams as they flickered through a window.

Henson’s 1987/88 series of neon-lit and collaged nightscapes of New York City and Los Angeles recycle the metropolises of the classic film noir and immediately signal the neo-noir films of the last three decades. The classic illusionism of the pictorial space has been dramatically shattered: images are cut-up and layered; those at street level are condensed and flattened; and people, vehicles and buildings are significantly detached from their immediate surroundings. Here we seem to have been placed in the urban nightlife of Martin Scorsese’s red-hot expressionist film Taxi Driver (1976), one the first films to initiate neo-noir cinema. Nor are they dissimilar to Scorsese’s much later Bringing Out the Dead (2000), a film about a burnt-out paramedic as a flawed urban saint. Moreover, the extraordinary long shots of Los Angeles with the pointillist-like iconography of city lights immediately brings to the fore noir’s perennial image of the city as an urban inferno, or, if you will, W H Auden’s memorable description of Los Angeles as “ the Great Wrong Place.”

In 1992/93 Henson began to produce a new substantial group of collages or “cut screens”, a selection of which were exhibited at the 1995 Venice Biennale. For this viewer, the “cut screens” section represents the tour de force of this show: when entering the room that exhibits these remarkably large-scale and vividly coloured kaleidoscopic collages of suburban youth in various sexual encounters, amid wrecked cars strewn in a nocturnal semi-rural site, or semi-dump site on the far outskirts of a town, is to experience an uncanny sensation of time travel, not to any ‘real’ places but to imagined ones. These dark, multifaceted landscapes with glimpses of faraway vistas of cities recalls George Miller’s apocalyptic visions in Mad Max (1979) and Mad Max: The Road Warrior (1982), while strangely they also suggest the influence of Luchino Visconti’s operatic realism and Werner Herzog’s iconoclastic romanticism. Nor should we overlook how Henson’s figures in their various staged configurations also suggest the famous desert orgy scenes in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1969).

Henson’s photographs are unique in recent Australian photo-based art because of their continuing Proustian capacity to suspend time and take us to dark spaces in our imagination by engaging in a sophisticated dialogue with cinema generally, but particularly with icons and images that are part of what James Naremore calls “the noir media scape.”[15] These are the icons and images that Varda would say have congealed and set, but, as Henson demonstrates, not for nothing have they done so.

Endnotes

[1] François Truffaut, The Films in My Life, (trans. Leonard Mayhew) New York, Simon Schuster, 1975, p. 27.

[2] Peter Craven, catalogue essay, in Mnemosyne Bill Henson, Salo, Zurich–Berlin–New York, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2005, pp. 356-57.

[3] Cited in Truffaut, op. cit.

[4] Sebastian Smee (in conversation with Bill Henson), “A Second Home, Where Everything is Innocent,” Art Monthly Australia, July 1996, reprinted in Mnemosyne Bill Henson, ibid., p. 439.

[5] Raymond Chandler, “The Simple Art of Murder”, a critical essay first published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1944.

[6] Judy Annear, catalogue essay, in Mnemosyne Bill Henson, op. cit., pp. 10-12.

[7] Chris Marker, A Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevitch, Artificial Eye, The Andrei Tarkovsky Companion, DVD release, 2007.

[8] Robert Frank’s book was first published in France, Les Américains (Robert Delprie, Paris) in 1958, and a year later in the US as The Americans by Grove Press.

[9] Alfred Appel, Jr., Nabokov’s Dark Cinema, New York, Oxford University Press, 1974, p. 219.

[10] ibid., p. 207.

[11] Cited in Jean-François Chevrier and Catherine David, “The Present State of the Image,” in Raymond Bellour, Catherine David and Christine Van Assche (eds), Passages de l’image, Barcelona, Centre Cultural De La Fundacio Caixa De Pensions / Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1990, p. 36.

[12] ibid.

[13] Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1965, p. 199.

[14] ibid.

[15] James Naremore, More Than Night, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998, p. 254.

Created on: Sunday, 7 November 2010