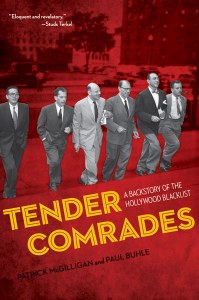

First published in 1997, Tender Comrades has been republished by University of Minnesota in their commendable series of reprints. Based at least conceptually on a never completed documentary film of the same title about the anti-Communist Hollywood blacklist, this anthology, edited by Patrick McGilligan and Paul Buhle, is however greatly expanded from the original project to include thirty-five in depth interviews with a B (Norma Barzman) to Z (Julian Zimet) list of film production workers, all of whom were drawn into the maelstrom of the Hollywood investigations of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The interviewees include the famous, like Alvah Bessie, Jules Dassin, Ring Lardner Jr., Abraham Polonsky, and John Wexley, and the not so famous, like Allen Boretz, Robert Leets, and Bess Tafel. And while the great majority of those queried were writers, like Walter Bernstein, Paul Jerrico, and Maurice Rapf, the authors also spoke to directors, like John Berry and Martin Ritt, actors, like Marsha Hunt and Lionel Stander, an animator (Faith Hubley) and a producer (Adrian Scott, i.e. his widow, Joan LaCour Scott). Excluded from the volume are any and all blacklistees who recanted, named names, and forever after bore the mark of a stool pigeon, indicating that even the book’s authors are unwilling to forgive, sympathize with or give voice to those who rightly or wrongly attempted to save their Hollywood careers.

There have been several important histories of the Hollywood anti-Communist blacklist. The standard work on the subject remains Larry Ceplair and Steve Englund’s The Inquisition in Hollywood (1980), which theorizes that the blacklist, instituted and maintained by film producers and various pressure groups, rather than by HUAC, was mainly directed at left-wing writers who had lead the unionization of Hollywood’s creative talent with the founding of the Writer’s Guild. Covering the same territory is Nancy Schwartz’s The Hollywood Writer’s Wars (1982), while Victor S. Navasky’s Naming Names (1980) focuses more exclusively on the history of the HUAC congressional hearings on Hollywood in 1947 and 1951, respectively. While these books provide sympathetic but generally objective histories of one of the most shameful periods in American politics and culture, the present anthology is defiantly subjective, offering the histories of individual actors in this national drama, their reactions to the blacklist, their betrayal by former friends and comrades in arms, and their lives after the blacklist. What emerges is an in-depth group portrait of the victims of blacklist, who to a surprising degree stuck together, even after they were demoted from Hollywood’s heavens to pariahs and exiles. Even thirty-forty years later, the interviewees consistently refuse to name their associates in the Communist Party of America, even those long dead.

Indeed, one of the more important discoveries in this conglomeration of individual fates is the realization that – at least for the writers – the blacklist was much less effective than previously assumed. Most visibly for insiders, Dalton Trumbo and Michael Wilson won Academy Awards under pseudonyms for Roman Holiday (USA 1953) and The Brave One (USA 1956), and The Bridge over River Kwai (UK/USA 1957), respectively, making a mockery of the blacklist. Less known was the fact that blacklisted writers and their friends created a vast network of fronts to sell their work to unsuspecting producers, moved to New York to work in television, where producers sometimes turned a blind eye to their talent’s radical past, or just loaned each other money and houses to bridge rough spots. Those blacklistees who chose exile in Europe – the only way to avoid a subpoena from HUAC, once they had been named, formed communities in Paris, Rome, London and Mexico City, passing work back and forth to each other. For example, in Paris, Jules Dassin, John Berry, Ben and Norma Barzman, and Lee Gold, among others, made films for television, allowing them a livelihood, even if producers often exploited them, paying rock-bottom prices for uncredited work. By the late1950s, the blacklist began to show serious cracks. Martin Ritt, for example, was hired by David Suskind as early as 1956 to direct Edge of the City (USA 1957). In 1959, Variety announced that Universal had hired Leonardo Bercovici to write a script for a new Tyrone Power film, but then Power died and the project was cancelled. A year later, Dalton Trumbo received official credit for Exodus (USA 1960) and Spartacus (USA 1960), officially breaking the blacklist, but some writers continued to use pseudonyms or fronts, because producers were still loath to hire radicals. Indeed, some writers used pseudonyms for so long, that when they finally used their real names again, they were thought to be using pseudonyms, e.g. when a trade paper announced that Tom August (pen name) sold a story under the name Alfred Lewis Levitt (real name).

Blacklisted actors and directors had a much harder time, because they of course could not resort to fronts or noms de plume. Bernard Vorhaus, for example, who beginning in 1925 had had a major directorial career in Hollywood and London, never made another film after being blacklisted in 1951. And while Joseph Losey, Jules Dassin, and Cy Endfield worked relatively steadily as ‘English’ and ‘French’ directors, John Berry and Abraham Polonsky only completed a handful of films after the blacklist ended in the early 1960s. For the actors, there was no possibility to work at all, forcing them to either give up the craft altogether, like Karen Morley, who had been incredibly prolific in the 1930s and 1940s or move to community theatre, like Jeff Corey. Others, like Marsha Hunt and Betsy Blair, saw their star careers fizzle to character roles that were few and far between. Only Lionel Stander, who remained on the blacklist from 1951 to 1963, was able to once again achieve star status after the blacklist ended.

One of the most interesting aspects of the book is its privileging of women’s stories, whether from the perspective of the widows of blacklisted writers or female radicals, who were themselves Hollywood writers. From the testimony of these women it becomes clear that, although the CPA paid lip service to women’s rights and to equality for all working class women, the reality of their members’ personal and public lives was that most remained male chauvinists. Wives and children were expected to make sacrifices for the careers of their husbands and fathers. Moreover, women, even if they were committed radicals, were not taken seriously by either the Party or their comrades as either political thinkers or professional writers. Norma Barzman, for example, complained that even after she started writing her own scripts, independently of her more famous husband, Bern Barzman, everyone around them assumed that Ben had written them. Joan Scott, the wife of Adrian Scott, noted that it was she who was expected to give up her career, every time her husband was forced to move. Jean Butler, the wife of writer Hugo Butler complained of similar treatment: “I look back and realize that these men were just as chauvinist as anyone. They endowed themselves with a larger-than-life quality, so that we (the wives) had to be the keepers of the flame and feed into that elevation… The American left male articulated a very good position on women’s rights. But he didn’t live it in his own domestic relationships.” (164) In reference to the upheaval the children of blacklistees experienced, Robert Lees notes that children suffered the most, because most were too young to understand what was going on.

To cope with the loss of identity, many of the blacklisted turned to analysis, which was yet another problem. The CPA was “violently anti-Freud” (170) and had instituted a strict ban against any Freudian analysis. As Paul Jarrico noted: “… no one who was in analysis could be in the Party. It was a security rule. So people going into therapy would either drop out or take a leave of absence.” (345) In 1946-47, a group of writers, including Albert Maltz, Leonardo Bercovici, and Waldo Salt, attempted to start a study group to discuss Freud and Marx, but it failed. To make matters worse, one Hollywood analyst who treated many of the writers, Phil Cohen, became a notorious facilitator for HUAC, guiding his patients, like Richard Collins to the committee to name names. It would take French post-structuralism to bring together Marx and Freud.

One of the most shameful aspects of this dark period, which Lillian Hellman has characterized as “the time of scoundrels”, was the role of the United States State Department, which seemingly worked hand in glove with the anti-Communist witch hunters to harass leftwing ex-patriots abroad. Julian Zimet, for example, reports that Embassy officials in Mexico City repeatedly tried to get him to inform on his blacklisted colleagues living in the country. The preferred tool for harassment by the State Department was the denial of passports to legitimate American citizens, once their passports expired, making it impossible for them to travel anywhere, much less leave the United States for work abroad, or return to the US, once they were abroad. It was not until 1958, after the Supreme Court suspended the State Department’s right to deny passports for political reasons that the blacklistees’ rights as American citizens were once again reinstated.

For anyone studying the effects of the anti-Communist blacklist on the lives of Hollywood filmmakers, this is both an excellent resource and a fascinating read.