2 or 3 Things I Remember or Should Have Known About Him.

Politically, we were beaten (Ken Jacobs, 52)

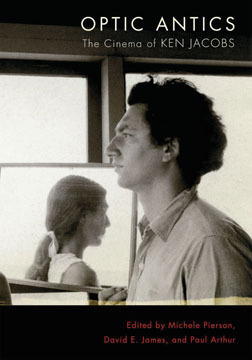

Optic Antics celebrates the work of Film Artist Ken Jacobs’ substantial and ongoing materialist practice, straddling more than 50 years, complicit in the 60s explosion of experimental film and now witnessing and commenting on the digital onslaught. This practice includes 16mm films that are recognized as foundation works for an experimental artist based cinema, celebrated and ongoing film performances and a renewed digital practice that re-animates historic 3-D images in flicker form. Its marginal but resistant position is evident in Paul Arthur’s assessment of “creative practices so evanescent, so immune to publicity and commodification that even meager perks such as rentals and prints sales are unobtainable.” (31) Scott Macdonald equates the problematic reception of Jacobs’ early work to “transforming courageous film artists into ‘displaced persons’” (177)

Edited by Michele Pierson, David E. James and Paul Arthur, Jacobs’ impact is further reflected by the ‘who’s who’ contributing to this publication, writers and practitioners plumbing the cutting edge of experimentation with the moving image. Our own Adrian Martin contributes a chapter linking Jacobs, Busby Berkeley and 20s Soviet Cinema, straddling Wollen’s two avant-gardes in a way Jacobs himself was apt to do in his SUNY, Binghamton Screening programs of films to his students. Martin notes in Jacobs’ strategies of recycling media rubble for the contemporary moment a visual form of Walter Benjamin’s text based working method.

Reading Optic Antics and revisiting Ken Jacobs’ sustained practice plumbed some personal recollections. These writings on a subjugated avant-garde recalled an early encounter with Ken and Flo Jacobs. In 1983 I was in New York touring a program of my own work and a program of Australian films that included Marcus Bergner, Marie Hoy, Chris Knowles and the Cantrills, screening at MOMA and the Collective for Living Cinema. I wanted to consult the oracle of Jonas Mekas and Jacobs on a feature length film, Homecomings, that I was having trouble completing. Mekas was kind enough to give me an audience on the basis of my purchase of the back catalogue of Film Culture, and told me to just finish it, as he had himself done with Reminiscences to Lithuania under the reality of a screening deadline to German television.

Jacobs took me on a tour of his neighborhood, walking in the gutters, as this was the safest and quickest way to move through the throng, pausing to talk to locals, describe shops and talk to their owners. Intermittently he turned to me, as I trekked behind him, to make some comment that often went straight past me as my senses were in overload on a multitude of levels and angles as a fledgling chewing on the big apple. I did not know how lucky I was to physically negotiate this social space so central to Jacobs’ practice. I went on some other walks with Ken and Flo to their studio and flat. This came back to me when I saw Circling Zero: Part One, We See Absence (2002). There is something about the way they move through these New York public spaces that make it their own, that bring certain details into view, and offer a particularly telling form of resistance in this film documenting the aftermath of the Twin Towers’ collapse a few blocks from their home. The film uses formalist, durational shots of emptiness above the New York skyline where the Twin Towers used to be – their memory still familiar, but now implied as a kind of bruise, an absent memorial, an afterimage inside the frame. These were images of mourning and after-shock marking the power of the implicit political and social register of a shunned reflexive first avant-garde that sits at the core of Jacobs’ practice. As Branden Joseph stresses, Jacobs’ work is “a sophisticated form of expression of suffering and oppression within contemporary, post-Holocaust society and a negative dialectic of the most advanced kind.” (Joseph, 45)

I remember hearing a version of Binghamton’s Nicholas Ray Ken Jacobs face-off, then already from a decade earlier, here documented in Larry Gottheim’s contribution to Optic Antics. I recall the residual visceral emotion that I witnessed in Flo and Ken’s recounting, in their support for each other as an honest and grounded emotional processing machine. This process was structured out of gestures, assertions, repetitions, reversals and echoes, requiring a positive emotional involvement that reflected the character and routine of the Jacobs performances. This dialogue expressed mutual respect rather than the suspicion and breakdown documented by Hollis Frampton in Critical Mass (dir. Hollis Frampton, 1971). Jacobs’ practice emanates out of the situation, the ties to community and relationship he embraces, it is where he lives, a body and senses way of working.

Both Mekas and Jacobs came to the Collective screening in 1983, Mekas’s wheeze from the audience signifying his presence. Tim Burns and Lindzee Smith supplied a local Oz contingent’s support. A few days after the screening Ken took the time to talk to me about these films and what stays with me is his point that the Australian work retained an innocence or purity, a directness to the medium lost, moved away from by the NY avant-garde. I took this as a compliment for all of us that I found no-where to place on my return. Seven years later, mixing in a Canadian alternative film scene pre-occupied with a sound-image dialectic, it made different sense. I then took this innocence as a liability, as limiting an Australian avant-garde to the visual realm and consequently vulnerable to a colonized framing by such self-situating visions as Cantrills Filmnotes. Where was the theory and debate? Where is the space for any critical thinking and critical community? Optic Antics deals it out in spades. Jacobs offered a departing gift, a shard of Masonite from one of his shadow-play performances. This and the bulk of the Film Culture and Millennium Journals never made it back home, getting lost somewhere in the U.S. postal system, on a slow boat to China, which is where we all are now.

Returning to review rather than recall I want to stress some details that jumped out at me. Ontic Antics displays Jacobs’ practice as interrogating the cinema apparatus and mining those ‘new’ perceptual moments that cinema brings; ‘a new kind of cinema experience’. (Michele Pierson, p.16) Federico Windhausen sees here the influence Hans Hoffman’s teaching of the history of visual art as a history of perceptual effects. (Windhausen , p. 235) Hoffman’s perceptual focus is evident in Jacobs’ description of Cezanne’s studies as exercises in seeing (p.168) and Flo’s description of a Mondrian painting as a motor (p.152) performing Hoffman’s Push and Pull.

In his Nervous System performances Jacobs performs his theories directly, ‘rorschaching’ (p.30) his audience. This Nervous System machine viewed at Rotterdam Film Festival a few years ago has what looks like a large fan in front of its two bulky projectors. Once the screening begins you realize it acts as a shutter to allow the inching of filmstrips through the two projector gates. Lewis Khlar describes this method as a practice that uses the found single frame to communicate with history. (p. 214) Paul Arthur describes this machine as ‘a two headed cinematic apparatus liberated from its linear shackles of 24 frames per second in order to stop and start, jump backward and forward at will. In turn, the movements of human shadows and other natural forms fed through the machine are blasted apart’ (p. 30). In her discussion of the experience of History in Jacobs’ New York Ghetto Fishmarket 1903 (2006) Pierson refers to the use of visual effect as part of a salvage operation on history. (p. 204)

Together these comments reminded me of Ulrich Baer’s invocation in Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma (2002) to reanimate the photographs of the Lodz Ghetto, echoing Walter Benjamin, ‘from the perspective of the defeated’ (Baer 2002, p. 128 [1] ) to bring back to life, to witness the erased personae that suffered the Final Solution there, to reclaim their gaze. Jacobs achieves such re-animation through acts of resistance, and this book and its contributors fly the flag for that marginal practice and its capacity for speaking the unspeakable.

[1] Baer, U 2002, Spectral Evidence: the photography of trauma, the MIT Press, Cambridge Mass.